Hamza

The Hamza ( Arabic همزة, DMG Hamza ; Persian همزه Hamze ; Urdu ہمزہ; in older German texts (up to the 19th century) also Hamsa , in other romanizations also Hamzah ) is a character of the Arabic script . It is used in several Arabic-based alphabets with different functions.

In Arabic, the grapheme becomes Hamza for the writing of the phoneme همز / Hamz / Compressibility 'used in the standard pronunciation of the unvoiced glottal plosives (also glottal , IPA : [ ʔ ] ; as in the German word Note [bəʔaxtə] in exact North German pronunciation) corresponds.

Hamza is either placed above or below a carrier symbol or written in an unconnected stand-alone form, the exact spelling is subject to detailed rules (see below). The character is not considered a letter in classical doctrine and, in contrast to the 28 characters of the Arabic alphabet, has no equivalent in any other Semitic script. Hamza did not come into being until the 8th century, when the letter Alif underwent a change in meaning and a new symbol for the glottic stroke was deemed necessary.

In other languages written in Arabic, Hamza marks a hiatus , indicates the beginning of a word with a vowel or is used as an umlaut or diacritical mark .

Appearance

In contrast to the 28 “real” Arabic letters, the appearance of the Hamza does not depend on its position in the word (initial, medial, final, isolated). The symbol only exists in one form, which in modern Arabic is above or below a vowel,كرسي / kursī / called 'armchair', or is to be placed “on the line”. In Arabic the letters Alif (ا) , Wāw (و) and Yāʾ (ي) , whereby Yāʾ as a Hamza bearer (except in Maghrebinic editions of the reading of the Nāfiʿ) loses his diacritical points. Hamza “on the line” means an unconnected Hamza without a carrier mark placed next to the preceding letter; In the Koran there are also strapless Hamza signs directly above or below the connecting line between two letters. Other characters for the Arabic phoneme Hamz are Madda and Wasla (see Tashkil ).

In the Arabic script of other languages, the Hamza can also be found above and below other carrier characters. As a diacritical mark , Hamza is used in the Pashtun script above the Ḥāʾ (ح) and in the Ormuri above the Rāʾ (ر) is used. In the Arabic script of Kazakh , a “high” Hamza is used as an umlaut; In Kashmiri , in addition to the "normal" one, a wavy Hamza is also used - both forms are used for vocalization and can appear above and below all consonant signs and Alif. Hamza can only be found at the end of the word via Čhōťī hē (ہ) and Baŕī yē (ے) in Urdu as well as in Persian above the Hāʾ (ه) .

If the carrier letter Alif follows a Lām , Hamza comes above or below the mandatory ligature Lām-Alif (لا) .

Origin and development of the sign

The invention of the grapheme Hamza is closely related to a change in the meaning of the letter Alif, which ceased to function as a sign for the glottic stroke around the 8th century and instead came into use as a vowel stretch sign.

The Arabic script probably developed from the Nabataean script , a consonant script in which - as in most Semitic alphabets - a glottic stroke was noted with the letter Ālaf . In Aramaic , this sound was articulated increasingly weakened; in Nabataean , Ālaf also took over the function of the character for a final / ā /. Already in this phase of its development Ālaf had two functions (symbol for glottic stroke and long / ā /), but it was only with the Alif of the Arabic script that the extension of a short / a / to a long / ā / in the middle of the word was marked:

Initially, long / ā / were marked with a small superscript Alif . Shortly before the time of the linguistic scholar al-Farāhīdī (8th century), however, a change was made to setting Alif as mater lectionis instead . The editing of the Koran had already been completed; its consonant skeleton was considered god given - it was not allowed to change it, but you could add (small or colored) signs. The use of (red) Alifs as signs of stretching was inconsistent, without a fixed plan and in several periods. In the course of time - especially in the Ottoman Empire - red alifs became normal alifs. In the Cairin edition of the Koran of 1924, over five thousand such inserted Dehnungsalif were removed from the text and replaced by superscript little alifs. In modern Arabic, too, a long / ā / sound is not written with Alif as mater lectionis , but with this optional auxiliary character.

Early systems for differentiating the vowelic and consonantic functions of a sign used different variants of additional points. A yellow or green point, which by its position above, next to or below the carrier symbol also expressed the vocalization, indicated the correct articulation of the carrier as Hamz; In another system, the glottal beat was marked by setting the vowel point twice on either side of the carrier mark.

The origin of today's symbol for the glottic stroke in the Arabic script (ء) is predominantly used, for example by Richard Lepsius and Kees Versteegh , in the initial form of the letter ʿain (ﻋ) supposed to be the symbol for the voiced pharyngeal fricative [ ʕ ], whose sound quality would come closest to that of Hamza. Heinrich Alfred Barb , on the other hand, cited several examples from the Arabic and Persian languages, from which he derived a modification to Hamza from the isolated form of Yāʾ without dots (ى) derived. According to Theodor Nöldeke , however, Barb's assumption is "entirely incorrect".

According to the historiolinguist Versteegh, the Arabic grammarian Abū l-Aswad ad-Duʾalī (7th century) is the inventor of the sign in its current form . Abū l-Aswad has begun to insert small ʿAins into texts where a Wāw, Yāʾ or Alif is pronounced as a long vowel in the dialects of the Hijāz , but as a glottic stroke in the Koran. The orientalist Gotthold Weil, however, attributes this innovation to al-Farāhīdī. According to Weil, al-Farāhīdī saw the use of Alif as mater lectionis as a risk of confusion with the glottic stroke, and therefore marked the consonantic Alif with a bookmark above.

In the beginning, Alif Kursī was always a Hamza. While Hamz has a phoneme character in classical Arabic, in non-classical Arabic, on which the Arabic spelling is based, it was only preserved in the wording and written in the form of an alif. In all other positions, Hamz was weakened by different types of Tachfīf al-hamza to / y / or / w /, dropped or replaced by a stretching of the preceding vowel. In the orthography of Classical Arabic, that character was the bearer of the Hamza sign, which in the non-classical orthography represented the weakened or replaced glottal beat - thus Yāʾ and Wāw also became possible Hamza carriers. If Hamz was omitted in non-classical Arabic, the classical orthography was given a Hamza without a carrier.

see also: History of the Arabic script

Hamza and the Arabic alphabet

Arab scholars disagree on both the Hamza and the Alif as to whether they should be called letters of the Arabic alphabet . In the classical doctrine, Alif has the status of a letter. Alif can be derived from the Phoenician alphabet and is therefore much older than Hamza. Hamza, however, stands for the sound represented by the forerunners of Alif.

The linguist al-Farāhīdī counted 27 or 28 letters in the Arabic alphabet in the 8th century (whether he deleted Hamza / Alif from the alphabet or only denied him the first place cannot be determined), his student Sībawaih 29 - he recognized both Hamza and also use Alif as a letter. Abū l-ʿAbbās al-Mubarrad , a grammarian from the 9th century, deleted Hamza from his alphabet because it had changed its appearance several times and was not a letter with a fixed shape, Alif added at the end of the alphabet and came up with 28 letters . The orientalist Gotthold Weil describes the inclusion of both Alif and Hamza in the alphabet as "linguistically and historically incorrect" - Hamza and the Dehnungs-Alif had a common form until the invention of the grapheme Hamza, as do the letters Wāw and Yāʾ today, which have a double function as a consonant and as a stretch sign.

“The history of the Alif sound in Arabic shows how much the lack of knowledge of the Semitic languages is felt by the Arabic national grammarians. With the help of that one can see that the Hamza is a component alien to the alphabet, that it is only a bookmark by default […], that the name of the first letter of the alphabet is Alif, which of course only means a loud consonant can be, since vowels are not found in any Semitic alphabet, and that finally Alif,و and ى [...] are to be treated as matres lectionis or expansion letters in the chapter on vowels. "

Hamza in the Arabic language

In the Arabic language Hamza grapheme is for the phoneme Hamz , which in the high-Arab the Phon [ ʔ ] (glottal stop) corresponds. The rules for spelling Hamza in modern standard Arabic have some differences from the orthography of the Koran. In modern Arabic, an Alif with Madda also contains the phoneme Hamz (followed by / ā /), whereas the Madda in the Koran is a pure elongation symbol that cannot only be placed above Alif.

Hamza and Madda are graphemes for the Hamzat al-qatʿ /همزة القطع / Hamzatu l-qaṭʿ / 'Cut-Hamza', also called separating alif at the beginning of the word . Hamzatu l-qatʿ is a full consonant, which can also be used as a radical as inقرأ / Qara'a / read 'shows up with a Shadda geminated and may occur at any position in the word. Wasla , grapheme for an "auxiliary shamza" ( Hamzat al-wasl /همزة الوصل / Hamzatu l-waṣl / ' Kopplungs -Hamza'), on the other hand, only exists at the beginning of the word and only contains a Hamz in the absolute initial sound.

If Hamza stands above or below a carrier vowel, this is an indication of the correct pronunciation, but cannot be pronounced itself. The spelling of Hamzas is subject to detailed rules, but Hamzas are often left out at the beginning of the word.

The Arabic article al- /الis not assimilated with words beginning with Hamza as before moon letters .

see also: The glottic stroke in Arabic

Hamza spelling rules in Modern Standard Arabic

|

Hamza forms in modern Arabic |

|

| Basic form: |

ء

|

| about Alif: |

أ

|

| under Alif: |

إ

|

| about Yāʾ: |

ئ

|

| about Wāw: |

ؤ

|

Beginning of word

At the beginning of a word, Hamza is always above or below an Alif - conversely, an Alif always wears a Hamza, Wasla or a Madda at the beginning of a word, but the Hamza is often omitted and the Wasla is even more common. If the beginning of the word is not the same as the beginning of a character string (in Arabic the article is al- and prepositions consisting of only one letter , conjunctions and particles such as wa- /و / 'And', bi- /ب / 'With, through' and li- /ل / 'For' appended to the following word), the spelling rules for a Hamza at the beginning of the word still apply.

Hamza is placed under the alif when the glottic beat is followed by a short or long / i / sound (examples:إسلام / ʾIslām ,إيمان / ʾĪmān / 'belief'). If it is followed by a short or long / u / , a diphthong or a short / a / , the Hamza comes on the Alif (أم / ʾUmm / 'mother',أول / ʾAuwal / 'beginning',أمر / ʾAmara / 'command'). If the word begins with a glottic stroke and a long / ā /, Alif should be placed with Madda (آل / ʾĀl / 'clan'). The Arabic language does not have an unvocalized consonant at the beginning of a word, this also applies to Hamza.

Middle of word

How Hamza is to be written in the middle of a word is determined by the two sounds surrounding the Hamza, whereby the sound immediately before the Hamza is ignored if it is a long vowel or a diphthong.

If Hamza remains unvocalized and is followed by a consonant, the vowel in front of the Hamza is decisive: If that vowel is a / i /, Hamza is closed via a Yā bei, with a / u / via a Wāw, with an / a / via an Alif write (بئر / biʾr / 'fountain',مؤمن / muʾmin / 'confessor, believer',رأس / raʾs / 'head'). If Hamza follows a non-vocalized consonant, the vowel following the Hamza is decisive according to the same principle, but Hamza always receives a (further) Yāʾ as a carrier after a Yā Träger.

If Hamza lies between two vowels, Hamza should be placed above a Yāʾ if at least one of the two surrounding vowels is an / i / (رئة / riʾa / 'lung'). If Hamza comes across at least one / u / but not one / i /, it comes across a Wāw (سؤال / suʾāl / 'question'). Hamza is only set over an alif if both surrounding voices are / a / (سأل / saʾala / 'ask'). With / āʾa /, / āʾā / and / ūʾa / Hamza is to be written “on the line” without a carrier (قراءة / qirāʾa / 'reading'), this prevents the direct encounter between two Alif in the script. If, according to the rules mentioned above, a Hamza is to be written with Alif as the carrier, followed by Alif as an expansion sign for the long / ā / sound, Alif is to be set with Madda (قرآن / qurʾān / 'Koran').

End of word

If Hamza follows a short vowel at the end of a word, this is decisive for the spelling of Hamza. In this case, Hamza should be written after an / i / over Yāʾ, over Wāw after a / u / and over an Alif after an / a / (قارِئ / qāriʾ / 'reader',لؤلؤ / luʾluʾ / 'pearl',خطأ / ḫaṭaʾ / 'error'). After a long vowel, diphthong or unvocalized consonant, Hamza is written “on the line” without a carrier (ماء / māʾ / 'water',شيء / šaiʾ / 'thing',بطء / buṭʾ / 'delay'). If Hamza is vocalized at the end of the word (means that the glottic beat is followed by a short vowel), the spelling only changes if Alif is followed by a Kasra or Kasratān with Hamza - Hamza is then to be placed under Alif (خطإ / ḫaṭaʾin ). If the / -aʾ / is the same as the trunk, Alif is always the carrier.

If Hamza moves into the middle of the word with a suffix , the rules of the middle position apply in principle with two exceptions:

- If Hamza follows a sign that cannot be connected to the left (ا د ذ ر ز و), and if it is vocalized with Fatha , it is without a carrier

- If Hamza follows a non-vocalized Yāʾ, Yāʾ stands as the carrier

If Hamza is connected with the ending of the indefinite accusative with Fathatān ( nunation ), special rules apply again: If Fathatān is otherwise always via an Alif or Alif maqsura , which as a Fathatān carrier have no sound value of its own, or Tāʾ marbūṭa , that is To put Fathatan directly over a strapless Hamza when it follows an Alif as a sign for a long / a /. If a word ends with an alif as the carrier of Hamza, Fathatān is to be placed over this sign. If a Hamza is only followed by an Alif with Fathatān, the rules of the middle position apply. If Hamza is the penultimate grapheme in the word between Yāʾ and Alif with Fathatān, Hamza is to be written with Yāʾ as the carrier.

If Yāʾ with Hamza is the last character of a word, the spelling with a strapless Hamza after a dotted Yāʾ is also used in its place (قارىء).

Deviations

These rules are not recognized by everyone and there are occasional deviations. With / aʾū / Alif is more often used as a carrier of hamza, with / ūʾū / a Yāʾ or Hamza without carrier. With / ī gerneū /, / āʾū / and / ʾū / after a consonant, Yāʾ is often used as a hamza carrier. There are several contradicting doctrines on these points. In older orthographies, the meeting of the same letters (as a carrier symbol of the Hamza and as a consonant or expansion symbol) was often avoided by placing Hamza without a carrier (رءوس / ruʾūs , common todayرؤوس, sometimes without a sign for the vowel stretch رؤس).

At تأريخ / taʾrīḫ / 'dating, history' has lost the articulation of Hamza placed above Alif over time, today is both in pronunciation and in spellingتاريخ / tārīḫ common. Wolfdietrich Fischer describes the spelling as an "isolated case of historical orthography"مائة instead of مئة / miʾa / 'hundred'; the classical orthography always uses Hamza "on the line" after a long vowel or sukun inside the word . In older manuscripts in particular, there are spellings that contradict today's orthography. The deviations range from the neglect of a Hamza in the final or the inside of the word, to the omission of the Hamza above the carrier symbol, to a substitution by Yāʾ.

Hamza in the Koran

In the Koran , in addition to the manifestations of modern standard Arabic, Hamza is also found strapless above and below the line (ــٔـ, ــٕـ) as well as not only above, but also below a Yāʾ. A strapless hamza above the line between Lām and Alif does not affect the formation of the Lām-Alif ligature.

the Hamza des Alif stands halfway next to it instead of above the sign, to indicate the vocalization with / u /; the hamza under the yāʾ is placed between the diacritical points

The writing rules of a Hamza in the Koran differ from those of modern standard Arabic : According to a Sukūn , a Hamza is placed in the middle of the word without a carrier either on or above the line. Hamza with Kasra in medial position is not placed above a Yāʾ but below it, with the Yāʾ remaining pointless. In order to avoid two identical characters in a row, Hamza is written without a strap, if it would otherwise have Wāw as a carrier in front of another Wāw or Yāʾ as a carrier in front of another Yāʾ. Likewise, Alif is omitted as a Hamza bearer before or after another Alif, so in some editions of the Koran words can begin with a Hamza on the line followed by an Alif (example:ءامنوا, however, in modern standard Arabic آمنوا). In all editions of the Koran, Madda is always an elongation symbol and does not contain a glottal stroke.

Two other Hamza variants have come down to us in Maghrebian Koran editions: Yāʾ retains his diacritical points in these as a Hamza bearer , with Alif as kursī , Hamza appears in three instead of two different positions. Below an alif, Hamza stands for a vocalization with / i /, as usual, but above the alif only for a vocalization with / a /. A kursī -alif vocalized with / u / carries Hamza at his side halfway up.

In the Koran, however, there are numerous deviations in the spelling of a Hamza. According to Theodor Nöldeke , "when you represent this consonant [...] the awkwardness of the oldest Qoran writers comes to the fore". In the dialect of the Quraish , the Arab tribe to which the Prophet Mohammed belonged, a Hamza was usually not articulated at all or as [ j ] or [ w ], which had a great influence on the Koran orthography, as well as on the Hijazi readings of the Koran but not to other Arabic dialects. Hamza is often omitted when it follows an unvocalized consonant, precedes or follows an / a /, or when two identical characters collide. If Hamza separates two vowels of different quality , the Koran writers, according to Nöldeke, expressed themselves "strangely" in many cases.

Transcription

When transliterating or transcribing Arabic texts into the Latin writing system , a hamza at the beginning of the word is not reproduced in many transcriptions. Transcription or transliteration of Hamza takes place at the DMG and EI as modifying right semicircle (< '>) at ISO 233 with an acute accent (<> when with carrier sign, single <ˌ>), with the inscription of UNGEGN and ALA with Apostrophe (<'>). The inscription of a Madda is done as the inscription of the Hamza with the following inscription of the Alif (in ISO 233, however, as <ʾâ>).

| Braille characters: | ⠄ P3 |

⠌ P34 |

⠳ P1256 |

⠽ P13456 |

| Hamza shape: | ء | أ/إ | ؤ | ئ |

In " Chat-Arabic " the number <2> is set for a Hamza. The Morse code for (a single) Hamza is <•>; the (clockwise) Arabic Braille has different equivalents for Hamza, depending on the carrier symbol.

Hamza in other languages

|

Additional Hamza forms of other languages |

|

| about Hāʾ: |

ۀ

final: ـۀ

|

| about Čhōťī hē: |

ۂ

final: ـۂ

|

| about Baŕī yē: |

ۓ

|

| about Ḥāʾ: |

ځ

|

| about Rāʾ: |

ݬ

|

| Alif with high hamza: |

ٵ

|

| Wāw with high hamza: |

ٶ

|

| U with high hamza: |

ٷ

|

| Yāʾ with high hamza: |

ٸ

|

| Above Wavy Hamza: |

ٲ

|

| Underneath Wavy Hamza: |

ٳ

|

| "Sindhi &": |

۽

|

The Hamza is also a component of several Arabic-based writing systems in other languages, but often takes on additional or different functions than in Arabic. Only languages are listed here in which the function of the Hamza sign extends beyond that of the grapheme for the glottic stroke - the rules for writing this sound in languages not listed here can nevertheless contradict those of the Arabic language.

Iranian languages

Persian

In the writing of the Persian language Hamza (Hamze) appears on the one hand in words of Persian origin, on the other hand in words of Arabic origin. In words of Arabic origin, it can appear in the medial or final position; Hamza is written with these words without a carrier or over Alif (Persian Aleph ), Wāw (Vāv) or Yāʾ (Ye) . The spelling of the Hamza does not always match that in the Arabic original, and since such a Hamza is unspoken in Persian, it is not always written.

“For the most part there are rules for the correct spelling, the form ﺋ Nevertheless, it loses none of its popularity. "

In words of Persian origin, Hamze can mark an Ezāfe ending. Above a Hāʾ (He) at the end of a word, it shows the ending / -eye /, above a Ye the ending / -iye /, but the hamze is not always set in these two as well as in other cases, it is found in modern texts in addition, instead of a hamze placed on top of the he, an isolated ye placed after it. According to Sebastian Beck in his Grammar of Neupersian (1914), this “Persian hämzä ” was derived from an overlaid Ye (in Persian always pointlessى) whose sound value it represents in this form. The Unicode character still bears the name "Arabic letter He with Ye above"; Beck himself calls this overlaid symbol - in accordance with its modern form - hämza .

The spelling Ye with Hamze before another Ye after the vowels / ā / or / u / is obsolete - today two normal Ye are used in their place. Also no longer in use is He with Hamze for the ending / -eī /, which is now written with He-Alef-Ye, where He and Alif are not connected (exampleخامنهای Chāmeneī ).

Also in some foreign words, for example in Gāzuil /گازوئيل / 'Gasöl', Hamza indicates the change between two vowels.

Sorani Kurdish

The Sorani -Kurdische used, similar to the Uighur, a <ﺋ> before most vowels at the beginning of a word. Only the / i / sound, which is not written in other positions in the word, is not used in the initial position with <ﺋ> initiated, but as Alif <ا> written; <ئا> as a digraph for an initial / a / can be replaced by <آ> be replaced.

Pashtun

In the Pashtun script , Hamza is used as a diacritical mark over the letters Ḥāʾ (Pashtun Hā-yi huttī ) and Yāʾ (Je) . Hā-yi huttī with Hamza, the letter Dze (ځ) , is pronounced regionally differently as [ d͡z ] or [ z ]; Je with Hamza (Fe'li Je) is one of the five variants of Je represented in Pashtun and stands for the ending [ -əy ] in verbs in the 2nd person plural.

In the Peshawar orthography - based on the Urdu script - there is also a Baŕī yē and Hāʾ (hā-yi hawwaz) with Hamza above , each as a symbol for vowels at the end of the word. Hā-yi hawwaz with Hamza is a sign for the vowel final / -a /, the Baŕī yē with Hamza sometimes replaces the characters Fe'li Je and Ṣchadzina Je.

The Ezāfe ending / -ʾi / is indicated by adding a Hamza. The Hamza forms of the Arabic language can be found in Arabic foreign words.

Ormuri

In Ormuri , a south-east Iranian language from South Waziristan with around 1000 speakers, there is the sound [ r̝ ], for which a Rāʾ is set with Hamza. The sound does not appear in any other Indo-Iranian language . The affricate [d͡z] is written as Ḥāʾ with Hamza.

Indo-Aryan languages

Urdu

Hamza has various functions in the Urdu script and appears "on the line" as well as via Yāʾ (Urdu: Čhōťī yē ), Wāw (Wāō) , Čhōťī hē (has the function of the Hāʾ of Arabic, but only in isolated form) and Baŕī yē .

For one thing, Hamza separates two vowels. In case ofإن شاءاﷲ, “ Inschallah ”, the spelling “on the line” is retained from the Arabic original. If the second vowel is an [ iː ] or [ e ], represented by Čhōťī yē or Baŕī yē, the hamza sits in front of that letter on an “armchair” (≈ Čhōťī yē). If the second vowel is a short [ ɪ ], this is also represented by a hamza on an "armchair". If the second vowel is a [ uː ] or [ o ] represented by a Wāō, the hamza can be placed on the Wāō, but is often left out. The vowel combinations [ iːɑ̃ ], [ iːe ] and [ iːo ] are also reproduced without Hamza .

A second purpose of the Hamza is to mark the Ezafe (Izāfat) . In Urdu, an Izāfat after Čhōťī yē or a consonant is marked with the optional vowel character Zer (corresponds to the Arabic kasra ); after a Baŕī yē it remains unscripted. If the first word of an Izāfat compound ends with a Čhōťī hē, a Hamza is placed over this symbol to mark the Izāfat; If the first word ends with an Alif or Wāō, the Izāfat is marked by a Baŕī yē, over which a Hamza can be placed.

To figures in the Islamic calendar from the Gregorian to distinguish data are provided with an Islamic Dō-čašmī hē, Gregorian times with a Hamza (١٢٣٤ ھ for 1234 AH; ۲۰۰۴ ءfor 2004 AD). The date hamza is a makeshift for a lowercase ʿAin, the first letter ofعيسوى / īsawī / “Christian” - in manuscripts and a good type set , the year is followed by a small high standing ʿAin. Another function of the stand- alone Hamza is to replace the decimal separator U + 066B, which looks similar to the Hamza (example:۲ ٬ ۰۰۰ء۵۰ for 2,000.50).

Kashmiri

In the Arabic script of Kashmiri , two different Hamza forms are used for vocalization. Translated a Hamza for the sound [ ə ], put below for the sound [ ɨ ] - the "normal" Hamza form is used for a short vowel and a wavy Hamza for a long vowel.

For an initial vowel , the Hamza must be placed above or below Alif, a short [ ə ] in the final is written with Hamza above Hāʾ. In the other positions, Hamza is placed above or below the immediately preceding consonant sign.

Sindhi

The Arabic script of Sindhi has a Hamza with two vertical lines below each other (۽) as a symbol for the word "and". The form of the decimal separator in the Sindhi Arabic script is similar to the Hamza. The Hamza above Yāʾ, as well as the single Hamza at the end of the word, is used as a hiatus sign.

Turkic languages

Uighur

In the Arabic script of the Uighur language , Hamza exists "on a tooth" (ﺋ). This character is used as an integral part of the isolated and initial form of the vowel mark (example Uyghur /ئۇيغۇر- before u /ۇ at the beginning of the word there is a <ﺋ>, the same vowel in the second syllable is without Hamza) and is placed in front of every vowel mark at the beginning of the syllable or word. The first character of a word is <ﺋ> thus the function of a dummy letter, which, for example, has an initial Alif in Pashtun.

Stands <ﺋ> medially or at the end of a word, it represents a hiatus , a syllable boundary; In pronunciation, this medial hamza is often realized as a long pronounced vowel. In this function, “Hamza on a tooth” does not count as a separate letter, but as a special spelling of vowels in the middle or end position and usually occurs in words of Arabic origin, where it replaces an ʿAin or Hamza of the original Arabic word.

“Hamza on a tooth” occurs in the middle of the word only in foreign and loan words with a few exceptions. In the other Uyghur scripts, a hiatus is only marked with a grapheme in the middle of the word, if at all.

Kazakh

The Arabic script of the Kazakh language , in use in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China , uses a "high Hamza" to indicate the beginning of a word with a sound in the vowel series / æ, ø, i, ʏ /. The high Hamza can be used in combination with Alif, Wāw, Yāʾ and U - the same characters without high Hamza represent the vowel sequence / a, o, ɯ, u /.

Chinese

| Xiao'erjing: | ءَ | اِئ | ـِئ | يُؤ | ـُؤ | ءِ | ـِؤ | ءُ | ءًا | ءٌ | ءٍ | ءْا |

| Pinyin : | a | ye | -ie | yue | -ue -üe |

yi | -egg | wu | on | en | yin | nec |

In the Arabic-based script Xiao'erjing , Hamza is part of several syllable endings and vowels in various forms. Glottal beats, although phonemic in Chinese, are not written in Xiao'erjing.

Character encoding

In Unicode , the Hamza is not only encoded as a combining diacritical mark , but also in an isolated form and as a unit with a carrier character. The high Hamza of the Kazakh Arabic script is coded both with its possible companions as a unit and as a combining symbol, the wavy Hamza of the Kashmiri only with Alif as the carrier.

All Hamza variants can be found in the Arabic Unicode block, except for the Re with Hamza, which is included in the Arabic block . These characters automatically adapt to their position in the word and appear accordingly in an isolated, final, medial or initial form. In the blocks Arabic Presentation Forms-A and Arabic Presentation Forms-B , most of the characters are listed again, as well as some ligatures. The characters of the last two Unicode blocks mentioned do not adapt to their position in the word.

| block | description | Code point | Unicode name | HTML | character |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | Hamza | U + 0621 | ARABIC LETTER HAMZA | & # 1569; | ء |

| Arabic | Hamza on Alif | U + 0623 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1571; | أ |

| Arabic | Hamza on Waw | U + 0624 | ARABIC LETTER WAW WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1572; | ؤ |

| Arabic | Hamza under Alif | U + 0625 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA BELOW | & # 1573; | إ |

| Arabic | Hamza about Ya | U + 0626 | ARABIC LETTER YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1574; | ئ |

| Arabic | Hamza across | U + 0654 | ARABIC HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1620; | ٔ |

| Arabic | below Hamza | U + 0655 | ARABIC HAMZA BELOW | & # 1621; | ٕ |

| Arabic | Alif with a wavy hamza above | U + 0672 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH WAVY HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1650; | ٲ |

| Arabic | Alif with a wavy hamza underneath | U + 0673 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH WAVY HAMZA BELOW | & # 1651; | ٳ |

| Arabic | high hamza | U + 0674 | ARABIC LETTER HIGH HAMZA | & # 1652; | ٴ |

| Arabic | Alif with high Hamza | U + 0675 | ARABIC LETTER HIGH HAMZA ALEF | & # 1653; | ٵ |

| Arabic | Waw with high hamza | U + 0676 | ARABIC LETTER HIGH HAMZA WAW | & # 1654; | ٶ |

| Arabic | U with a high hamza | U + 0677 | ARABIC LETTER U WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1655; | ٷ |

| Arabic | Ya with high hamza | U + 0678 | ARABIC LETTER HIGH HAMZA YEH | & # 1656; | ٸ |

| Arabic | Hamza about Ḥa | U + 0681 | ARABIC LETTER HAH WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1665; | ځ |

| Arabic | Hamza on Ha | U + 06C0 | ARABIC LETTER HEH WITH YEH ABOVE | & # 1728; | ۀ |

| Arabic | Hamza on Chhoti He | U + 06C2 | ARABIC LETTER HEH GOAL WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1730; | ۂ |

| Arabic | Hamza on Bari Ye | U + 06D3 | ARABIC LETTER YEH BARREE WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1747; | ۓ |

| Arabic | Sindhi-And | U + 06FD | ARABIC SIGN SINDHI AMPERSAND | & # 1789; | ۽ |

| Arabic, supplement | Hamza on Re | U + 076C | ARABIC LETTER REH WITH HAMZA ABOVE | & # 1900; | ݬ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Hamza over Ha (isolated) | U + FBA4 | ARABIC LETTER HEH WITH YEH ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 64420; | ﮤ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Hamza on Ha (final) | U + FBA4 | ARABIC LETTER HEH WITH YEH ABOVE FINAL FORM | & # 64421; | ﮥ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Hamza via Bari Ye (isolated) | U + FBB0 | ARABIC LETTER YEH BARREE WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 64432; | ﮰ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Hamza on Bari Ye (final) | U + FBB1 | ARABIC LETTER YEH BARREE WITH HAMZA ABOVE FINAL FORM | & # 64433; | ﮱ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Hamza over U (isolated) | U + FBDD | ARABIC LETTER U WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 64477; | ﯝ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif (isolated) | U + FBEA | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF ISOLATED FORM | & # 64490; | ﯪ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif (final) | U + FBEB | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF FINAL FORM | & # 64491; | ﯫ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ä (isolated) | U + FBEC | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH AE ISOLATED FORM | & # 64492; | ﯬ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ä (final) | U + FBED | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH AE FINAL FORM | & # 64493; | ﯭ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Vaw (isolated) | U + FBEE | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH WAW ISOLATED FORM | & # 64494; | ﯮ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Waw (final) | U + FBEF | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH WAW FINAL FORM | & # 64495; | ﯯ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and U (isolated) | U + FBF0 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH U ISOLATED FORM | & # 64496; | ﯰ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and U (final) | U + FBF1 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH U FINAL FORM | & # 64497; | ﯱ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ö (isolated) | U + FBF2 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH OE ISOLATED FORM | & # 64498; | ﯲ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ö (final) | U + FBF3 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH OE FINAL FORM | & # 64499; | ﯳ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Yu (isolated) | U + FBF4 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH YU ISOLATED FORM | & # 64500; | ﯴ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Yu (final) | U + FBF5 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH YU FINAL FORM | & # 64501; | ﯵ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and E (isolated) | U + FBF6 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH E ISOLATED FORM | & # 64502; | ﯶ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and E (final) | U + FBF7 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH E FINAL FORM | & # 64503; | ﯷ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and E (initial) | U + FBF8 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH E INITIAL FORM | & # 64504; | ﯸ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif maqsura (isolated) | U + FBF9 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF MAKSURA ISOLATED FORM | & # 64505; | ﯹ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif maqsura (final) | U + FBFA | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF MAKSURA FINAL FORM | & # 64506; | ﯺ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif maqsura (initial) | U + FBFB | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF MAKSURA INITIAL FORM | & # 64507; | ﯻ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Jim (isolated) | U + FC00 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH JEEM ISOLATED FORM | & # 64512; | ﰀ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ḥa (isolated) | U + FC01 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH HAH ISOLATED FORM | & # 64513; | ﰁ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Mim (isolated) | U + FC02 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH MEEM ISOLATED FORM | & # 64514; | ﰂ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif maqsura (isolated) | U + FC03 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF MAKSURA ISOLATED FORM | & # 64515; | ﰃ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ya (isolated) | U + FC04 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH YEH ISOLATED FORM | & # 64516; | ﰄ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ra (final) | U + FC64 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH REH FINAL FORM | & # 64612; | ﱤ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Zay (final) | U + FC65 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ZAIN FINAL FORM | & # 64613; | ﱥ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Mim (final) | U + FC66 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH MEEM FINAL FORM | & # 64614; | ﱦ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Nun (final) | U + FC67 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH NOON FINAL FORM | & # 64615; | ﱧ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Alif maqsura (final) | U + FC68 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH ALEF MAKSURA FINAL FORM | & # 64616; | ﱨ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ya (final) | U + FC69 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH YEH FINAL FORM | & # 64617; | ﱩ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Dschim (initial) | U + FC97 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH JEEM INITIAL FORM | & # 64663; | ﲗ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ḥa (initial) | U + FC98 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH HAH INITIAL FORM | & # 64664; | ﲘ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Cha (initial) | U + FC99 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH KHAH INITIAL FORM | & # 64665; | ﲙ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligatua Ya mid Hamza and Mim (initial) | U + FC9A | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH MEEM INITIAL FORM | & # 64666; | ﲚ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ha (initial) | U + FC9B | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH HEH INITIAL FORM | & # 64667; | ﲛ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Mim (medial) | U + FCDF | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH MEEM MEDIAL FORM | & # 64735; | ﳟ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-A | Ligature Ye with Hamza and Ha (medial) | U + FCE0 | ARABIC LIGATURE YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE WITH HEH MEDIAL FORM | & # 64736; | ﳠ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza isolated | U + FE80 | ARABIC LETTER HAMZA ISOLATED FORM | & # 65152; | ﺀ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza over Alif (isolated) | U + FE83 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 65155; | ﺃ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza on Alif (final) | U + FE84 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA ABOVE FINAL FORM | & # 65156; | ﺄ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza over Waw (isolated) | U + FE85 | ARABIC LETTER WAW WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 65157; | ﺅ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza on Waw (final) | U + FE86 | ARABIC LETTER WAW WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 65158; | ﺆ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza under Alif (isolated) | U + FE87 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA BELOW ISOLATED FORM | & # 65159; | ﺇ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza under Alif (final) | U + FE88 | ARABIC LETTER ALEF WITH HAMZA BELOW FINAL FORM | & # 65160; | ﺈ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza over Ya (isolated) | U + FE89 | ARABIC LETTER YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 65161; | ﺉ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza on Ya (final) | U + FE8A | ARABIC LETTER YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE FINAL FORM | & # 65162; | ﺊ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza over Ya (initial) | U + FE8B | ARABIC LETTER YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE INITIAL FORM | & # 65163; | ﺋ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza on Ya (medial) | U + FE8C | ARABIC LETTER YEH WITH HAMZA ABOVE MEDIAL FORM | & # 65164; | ﺌ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza via Lam-Alif (isolated) | U + FEF7 | ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF WITH HAMZA ABOVE ISOLATED FORM | & # 65271; | ﻷ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza on Lam-Alif (final) | U + FEF8 | ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF WITH HAMZA ABOVE FINAL FORM | & # 65272; | ﻸ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza under Lam-Alif (isolated) | U + FEF9 | ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF WITH HAMZA BELOW ISOLATED FORM | & # 65273; | ﻹ |

| Arabic forms of presentation-B | Hamza under Lam-Alif (final) | U + FEFA | ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF WITH HAMZA BELOW FINAL FORM | & # 65274; | ﻺ |

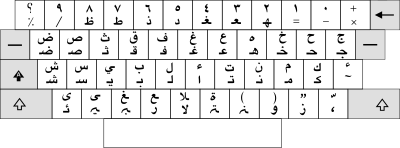

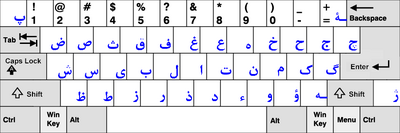

The Hamza and Madda variants of the Arabic language are coded in Windows-1256 , MacArabic , ISO 8859 , ISO 8859-6 , code page 708 , code page 720 and code page 864 , respectively. ArabTeX is adapted to the needs of all the Arabic scripts listed here, including Quranic Arabic. In Arabic keyboard layouts , in addition to Hamza and Madda, the finished combinations of carrier letters plus Hamza or Madda are usually available.

literature

About the Arabic language

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition . Volume 3. 1971; Pp. 150-152

- MAS Abdel Haleem: Qur'ānic Orthography: The Written Representation Of The Recited Text Of The Qur'ān . In: Islamic Quarterly: a Review of Islamic Culture, 38/3, 1994, pp. 171-92

- El-Said M. Badawi, MG Carter, Adrian Gully: Modern written Arabic: a comprehensive grammar . Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-13085-1

- Heinrich Alfred Barb: The system of the Hamze orthography in the Arabic script . Publisher by Karl Helf, 1860.

- Wolfdietrich Fischer : Grammar of Classical Arabic . Harrassowitz, 2002. ISBN 978-3-447-04512-4

- Richard Lepsius : About the Arabic speech sounds and their transcription: along with some explanations about the hard i-vocal in the Tartar, Slavic and Romanian languages . Dümmler, 1861; Pp. 96-157

- Günther Krahl, Wolfgang Reuschel, Eckehard Schulz: Textbook of modern Arabic . Langenscheidt Verlag Enzyklopädie, 1995. ISBN 978-3-324-00613-2

- Theodor Nöldeke : History of the Qorâns . Verlag der Dieterichschen Buchhandlung, 1860.

- Gotthold Weil : The treatment of Hamza-Alif in Arabic, especially according to the teachings of az-Zamaḫšarî and Ibn al-Anbârî . In: Journal of Assyriology and Related Fields , Volume 19, 1905-1906, pp. 1-63.

To other languages

- Rozi Khan Burki: Dying Languages; Special focus on Ormuri . In: Pakistan Journal of Public Administration , December 2001, Volume 6, No. 2

- Michael Friedrich, Abdurishid Yakup: Uyghur textbook . Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-89500-299-2

- John Mace: Persian grammar: for reference and revision . Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7007-1694-4

- Mohammad-Reza Majidi: The Arabic-Persian Alphabet in the Languages of the World . Buske, 1984. ISBN 978-3-87118-613-4

- WM Thackston: ورديى سۆرانى زمانى- Sorani Kurdish - A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings . (PDF; 848 kB)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ for example: Leopold Göschl: Brief grammar of the Arabic language with a Chrestomathie and the corresponding dictionary , Vienna 1867, view in the Google book search

- ↑ a b c Weil 1905–1906: pp. 11–13

- ↑ a b c The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 3. 1971; Pp. 150-152

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: pp. 313-315

- ↑ a b M. AS Abdel Haleem: Qur'ānic Orthography: The Written Representation Of The Recited Text Of The Qur'ān . In: Islamic Quarterly 1994; Pp. 171-192

- ↑ a b Lepsius 1861, p. 143 f.

- ↑ a b Kees Versteegh: The Arabic language . Edinburgh University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7486-1436-3 ; P.56

- ↑ Heinrich Alfred Barb: About the character Hamze and the three associated letters Elif, Waw and Ja of the Arabic script . Kgl. Hof & Staats Druckerei, 1858. pp. 95ff

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: S: 314

- ↑ Weil 1905–1906: p. 11

- ^ Mary Catherine Bateson: Arabic language handbook . Georgetown University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-87840-386-8 ; P.56

- ↑ Fischer 2002: p. 10f

- ↑ Weil 1905-1906: pp. 9-11

- ↑ Weil 1905-1906: pp. 13-14

- ↑ a b Badawi, Carter, Gully 2004: pp. 11-14

- ↑ Weil 1905–1906: p. 7

- ↑ Fischer 2002: p. 14

- ↑ a b c d Krahl, Reuschel, Schulz 1995: pp. 401–404

- ↑ a b c Fischer 2002: p. 11

- ↑ cf. Raif Georges Khoury: ʿAbd Allāh ibn Lahīʿa (97-174 / 715-790): juge et grand maître de l'école égyptienne . Otto Harrassowitz, 1986. ISBN 978-3-447-02578-2 ; Pp. 236–239, as well as Miklós Murányi : ʿAbd Allāh b. Wahb: al-Ǧāmiʿ (The Koranic Studies ) . Otto Harrassowitz, 1992. ISBN 978-3-447-03283-4 ; P. 2

- ^ S. Muhammad Tufail: The Qur'ān Reader. An Elementary Course in Reading the Arabic Script of the Qur'ān (PDF; 8.3 MB) 1974

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: p. 256

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: p. 257

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: p. 281

- ↑ Nöldeke 1860: p. 257f

- ↑ The transliteration of the Arabic script in its application to the main literary languages of the Islamic world . ( Memento of the original from July 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.3 MB) German Oriental Society, Leipzig 1935

- ↑ Overview of various transliterations of Arabic (PDF; 184 kB) on transliteration.eki.ee

- ↑ a b Standard braille 6 dots for Hebrew and Arabic ( Memento of the original from February 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on ofek-liyladenu.org.il ; Arabic Braille . on tiresias.org

- ↑ David Palfreyman & Muhamed al Khalil: “A Funky Language for Teenzz to Use”: Representing Gulf Arabic in Instant Messaging Zayed University, Dubai 2003

- ↑ List of Morse codes from various scripts ( Memento of March 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) on homepages.cwi.nl

- ↑ a b c Mace 2003: pp. 17-19

- ↑ Faramarz Behzad, Soraya Divshali: Persian Language Course: An Introduction to the Persian Language of the Present . Edition Zypresse, 1994. ISBN 3-924924-05-8 ; P. 34f

- ↑ Sebastian Beck: Neupersische Konversations-Grammar with special consideration of the modern written language . Julius Groos Verlag, 1914. p. 14

- ↑ WM Thackston:ورديى سۆرانى زمانى- Sorani Kurdish - A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings . (PDF; 848 kB) on fas.harvard.edu , p. 5

- ↑ Romanization of the Pashtun script (PDF; 140 kB) on loc.gov

- ↑ Burki 2001

- ↑ a b c Richard Ishida: Urdu script notes on rishida.net . 2006

- ↑ Ruth Laila Schmidt: Urdu, an essential grammar . Routledge, 1999. ISBN 0-415-16381-1 ; P. 247

- ↑ Urdu Design Guide ( Memento of November 9, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) on tdil.mit.gov.in (PDF)

- ↑ Majidi 1984, p. 78 f.

- ↑ Sindhi Design Guide ( Memento of November 9, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) on tdil.mit.gov.in (PDF)

- ↑ a b Reinhard F. Hahn, Ablahat Ibrahim: Spoken Uyghur . University of Washington Press, Seattle / London 1991, ISBN 0-295-97015-4 , pp. 95 f.

- ↑ a b Friedrich, Yakup 2002, p. 2

- ^ A b Jean Rahman Duval, Waris Abdukerim Janbaz: An Introduction to Latin-Script Uyghur . (PDF; 462 kB) 2006, p. 4, 11 f.

- ^ Friedrich, Yakup 2002: p. 7

- ↑ Klaus Lagally: ArabTeX Typesetting Arabic and Hebrew User Manual Version 4.00 (PDF; 612 kB) 2004