United Nations peacekeeping forces

As peacekeepers of the United Nations or UN peacekeepers , colloquially UN soldiers or peacekeepers , military units are referred to those adopted by the member countries United Nations ((UN) peacekeeping operations English peacekeeping operations be) provided and are under the command of the UN. The UN blue helmets received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1988 for their commitment to securing world peace . The United Nations Security Council decides on United Nations peacekeeping operations . For the implementation of the in's secretariat is settled by the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations ( English Department of Peacekeeping Operations ) responsible.

history

Military officers as mediators were first deployed in 1947 as part of the United Nations Special Committee on the Balkans (UNSCOB).

The first deployment of unarmed UN military observers took place in 1948 as part of the United Nations Armistice Surveillance Organization (UNTSO) in the Palestinian War .

In the course of the Suez Crisis in 1956, the United Nations Emergency Response Force (UNEF) was the first to set up an armed unit.

At the suggestion of UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld, the United Nations Operation in Congo (ONUC), dispatched during the 1960 Congo crisis , used the blue helmets and the words “UN” on their military vehicles for the first time.

Peace missions

The peacekeeping or peacekeeping mission is a form of deployment of military forces by the United Nations. It is to be distinguished from the observer mission and the enforcement of peace under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations. Like all armed operations of the United Nations, it requires a corresponding resolution by the UN Security Council that defines the type, scope and duration of the operation.

A United Nations peace mission only takes place with the consent of the government of the host country in which its units operate, or with all of the conflicting parties there. This regulation is intended to prevent the blue helmets from getting caught between the fronts and becoming part of the conflict. Their troops never have a combat mission, but they are armed and at least to some extent authorized to use their weapons. They are thus empowered to defend themselves and in some cases their position as well as to guarantee their freedom of movement. Basically, a significant UN presence calms the conflict and ensures security for the population, as the President of Blue Shield International Karl von Habsburg notes during a visit to the UNIFIL Austrian camp in Lebanon. The instruments of a peace mission include the establishment of investigative commissions, mediation between conflicting parties, appeals to the international court of justice in The Hague insofar as both parties to the dispute have submitted to it, the formation of UN-controlled buffer zones, the deployment of election observers such as B. at the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET).

United Nations peace missions have so far mostly served as humanitarian aid , monitoring a ceasefire such as B. the United Nations peacekeeping force in Cyprus (UNFICY), the disarmament of parties to the civil war such as the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ) or securing a decolonization process such as B. the United Nations Security Force in West New Guinea (UNSF). In this sense, a peace mission serves as a peacekeeping or police and order force of the world organization. Additional tasks may include supporting the state bureaucracy or assisting with the democratization process . This also includes cooperation with NGOs, such as with the International Committee of the Blue Shield (Association of the National Committees of the Blue Shield, ANCBS) with regard to the protection of cultural property .

Overall, there are differences with regard to the modalities of the deployment of the various missions, but the system-based options for using armed force create situations in which there is scope for the application of international martial law . Since the United Nations is an international organization, but only states can accede to the agreement on the international law of war, the legal status of the peace missions in many specific legal questions is still open and unresolved.

Inserts ( missions )

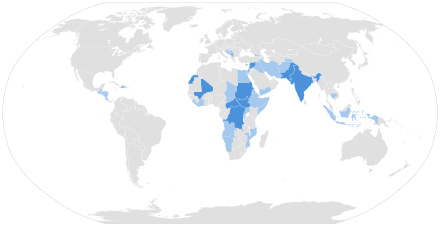

Since 1948 there have been a total of 71 United Nations peacekeeping operations. There are currently 14 ongoing missions, most of them in Africa and the Middle East.

The end of 2018 were, according to the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) nearly 90,000 soldiers (about 75,000) and police (10,000), military observers and staff from 121 countries, mainly from developing countries for peacekeeping active. The proportion of women is around five percent. The largest troop contributors are Ethiopia with 7,597, Bangladesh with 6,624, Rwanda with 6,528, India with 6,445, Nepal with 6,098 and Pakistan with 5,262. Germany ranks 47th with 537 soldiers . For some countries, this participation is an important source of foreign currency. The UN pays 1,332 US dollars per month for each blue helmet soldier . Bangladesh receives around $ 200 million in recompensation annually. Furthermore, a good relationship with the UN is an important reason why the army is holding back domestically.

By the end of 2018, around 3800 members of UN peacekeeping missions from 43 countries had lost their lives during the operation, including 2734 soldiers, 90 military observers, 278 police officers, 396 local employees, 259 foreign civilian employees and 35 other emergency services. The figures include various causes of death such as fighting, accidents and illness. So far 44 people from Austria have been killed in the course of blue helmet missions, 17 from Germany and 3 from Switzerland .

financing

The budget for peacekeeping operations is US $ 6.7 billion per year (July 1, 2018 - June 30, 2019), accounting for less than 0.5 percent of annual global military spending. The ten largest contributors are the United States (28.5 percent), China (10.3 percent), Japan (9.7 percent), Germany (6.4 percent), France (6.3 percent), and Great Britain (5th , 8 percent), Russia (4 percent), Italy (3.8 percent), Canada (3 percent) and Spain (2.5 percent).

education

The core of peacekeeping forces are military observers, who usually have to complete a military observer course at a UN-certified training institution. The course is called "Military Expert on Mission" (UNMEoM) or traditionally "Military Observer Course" (UNMOC) and is offered worldwide by special UN training centers. a. in India, Finland, Bangla Desh, Thailand, Vietnam, China etc. For the German-speaking areaː In Germany, the course is provided by the United Nations Bundeswehr Training Center , in Austria by the Austrian Armed Forces International Center (AUTINT) and in Switzerland by the "Training Center of the Swiss Army International Command "(TC SWISSINT). Together with the Dutch school “for Peace Operations” (NLD SPO), these centers form the training and cooperation network Fo (u) r Peace Central Europe, particularly for UN training . The "UN Staff Officer Course" (UNSOC) is offered for use in higher staffs of the UN peacekeeping forces; In Germany, the Bundeswehr Leadership Academy conducts this course once a year.

Problems and criticism

The past has shown that the UN blue helmets have not always been able to secure peace. It turned out that the provision of troops by the UN members on a voluntary basis does not work. In theory, around 150,000 men are regularly reported as available, but when it comes to specific missions, the governments only provide a fraction of the officially available troops.

In practice, including as many countries as possible in the peacekeeping force also turns out to be ineffective. Unclear command structures, language barriers and a lack of cooperation (due to technical or human inadequacies) lead to organizational deficits.

But the bureaucracy of the UN Security Council itself, which is the only UN body able to issue mandates for blue helmet operations, has been the target of criticism in the past. In 1994, when Rwanda had to act quickly in the face of massacres , it took the Security Council three weeks to take the necessary action. In the past, unsuccessful blue helmets were also due to the wrong mandates given to the peacekeeping forces. Often they could not even defend themselves due to a lack of armament and were taken hostage. It also happened again and again that blue helmets were sent to simmering trouble spots to maintain peace : “ You send armed forces to maintain a peace that does not exist at all ” ( France Soir ). As a result, the blue helmets were constantly involved in the clashes.

Another striking example was UN resolution 819 , which declared Srebrenica a UN protection zone on April 16, 1993 . About 400 Dutch blue helmet soldiers of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) under the command of Thomas Karremans were deployed for security . On April 19, 1995, the city of Srebrenica surrendered to the Bosnian-Serbian besiegers and the blue helmet soldiers were not able to protect the civilian population due to their mandate. As a result of these events, the Srebrenica massacre took place .

Another problem was highlighted by the Brahimi Report in 2000 . He found that the operations of 27,000 blue helmets around the world at New York's UN Headquarters , the Main Peacekeeping Operations Department (DPKO), were planned, supported and monitored by only 32 military experts, and that only 9 police officers were responsible for the 8,000 police officers there . The special position of the US blue helmets has often been a cause for criticism. The US government fears that politically motivated charges may be brought against its own troops and therefore insists on the immunity of its own troops.

In order to be able to counter a number of the problems listed, peacekeeping by the United Nations is increasingly taking place by assigning a specific mandate to act: The UN assigns a mandate to an external organization for peacekeeping in the form of a mandate formulated by the Security Council. Either it is a single state, a group of states, or another international organization. However, this approach is associated with risks, for example subcontractors could deviate from the mandate and pursue their own goals. An alternative would be a permanent UN reaction force, as provided for in Article 43 of the UN Charter . However, the relevant agreements are still missing.

Human rights organizations also see the stationing of peacekeeping forces as the cause of the steep rise in trafficking in women for forced prostitution in the respective regions. Thus, for example Kosovo since the deployment of international peacekeeping forces ( KFOR ) and the establishment of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo has become the main destination for women and girls (UNMIK). The number of registered establishments in which women have to work as forced prostitutes rose from 18 in 1999 to over 200 at the end of 2003. This situation is exacerbated by the soldiers' immunity, who protect them from prosecution in the event of human rights violations . UNMIK has now recognized the problem and taken some measures. Among other things, a "black list" of around 200 bars and nightclubs was drawn up that UN employees and soldiers are not allowed to visit. In 2000, a UNMIK special unit against trafficking in women and prostitution ( TPIU ) was founded and in January 2001 UNMIK issued a guideline that stipulates that both trafficking and knowingly sexual intercourse with trafficked women are a criminal offense. These measures are welcomed, but from the perspective of human rights organizations they are not yet sufficient.

According to a video from 2012, Austrian blue helmets from UNDOF Vorteil allowed 8 Syrian police officers to pass without warning, even though they knew that this would drive them into a fatal ambush.

On January 30, 2016, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Anthony Banbury announced that UN soldiers were guilty of at least 69 sexual abuse and exploitation in 2015. Including 22 cases in the Central African Republic .

literature

- Francisca Landshuter: The peace missions of the United Nations. A security concept in transition , Berlin studies on international politics and society, Vol. 4, Weißensee Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-89998-112-4 .

- Joachim Koops , Norrie MacQueen, Thierry Tardy, Paul D. Williams: The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations , Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, ISBN 978-0-19-880924-1 .

- James Sloan: The Militarization of Peacekeeping in the Twenty-first Century , Studies in international law Vol. 35, Hart Pub Limited, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-1-84946-114-6 .

Web links

- UNRIC: What are peacekeeping operations?

- Graphic: UN peace operations: Past and current operations (status: Sept. 2009) , from: Figures and facts: Globalization , www.bpb.de

- UN peacekeeping mission. UN basic information 39th German Society for the United Nations, Berlin, August 2008 (PDF, 360 KiB)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1988 award ceremony for the United Nations peacekeeping forces

- Report of the panel of experts on UN peace operations (Brahimi Report) (PDF, 378 KiB)

- United Nations Peacekeeping. Website of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christoph Matzl "UN Mission in Lebanon. Where Austria's Soldiers Secure the Easter Peace" in Kronenzeitung on April 20, 2019.

- ^ Peacekeeping Operation List. In: un.org. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Troops and Police Contributions. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Financing peacekeeping. United Nations Peacekeeping. Retrieved April 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Mohammad Humayun Kabir: Globally and locally meaningful. D + C, December 18, 2013. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- ^ Fatalities (number of victims). Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ How we are founded. United Nations Peacekeeping, accessed January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Comprehensive review of the whole question of peacekeeping operations in all their aspects In: Peacekeeping Resource Hub. January 18, 2008.

- ^ Matthias Dembinski / Christian Förster: The EU as a partner of the United Nations in securing peace. Between universal norms and particular interests . ( Memento of March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 272 kB) PRIF Report 7/07, Frankfurt a. M .: Hessian Foundation for Peace and Conflict Research, 2007

- ↑ Andreas Bummel: Future of blue helmets: On the way to a permanent UN reaction force. In: gfbv.it. December 18, 2003, accessed August 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Serbia and Montenegro - look and act: Kosovo: trafficking in women and forced prostitution Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. In: Amnesty International . June 2004.

- ↑ UN blue helmets are said to have not warned police officers of an ambush in: Spiegel Online, April 27, 2018, accessed on April 30

- ↑ Offenses committed by peacekeepers: Sexual abuse by UN soldiers confirmed in 69 cases. FAZ.net , January 30, 2016, accessed January 30, 2016 .