Schartenberg castle ruins

| Schartenberg castle ruins | ||

|---|---|---|

|

The keep |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Groppeschloss, Schartenburg | |

| Creation time : | built at the beginning of the 11th century . mentioned 1020/1124 |

|

| Castle type : | Hilltop castle | |

| Conservation status: | Part of the keep, neck ditch, wall remains | |

| Place: | Zierenberg | |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 23 '27.2 " N , 9 ° 18' 29.2" E | |

| Height: | 389.5 m above sea level NHN | |

|

|

||

The castle ruin Schartenberg , also called Groppeschloss or Schartenburg , is the ruin of a hilltop castle near Zierenberg in the Kassel district in northern Hesse . First mentioned in a document in 1124, Schartenberg Castle was described as abandoned and dilapidated in 1518. Parts of the keep as well as the remains of the neck ditch and walls have been preserved. The Groppeschloss once stood right next to Schartenberg Castle .

Geographical location

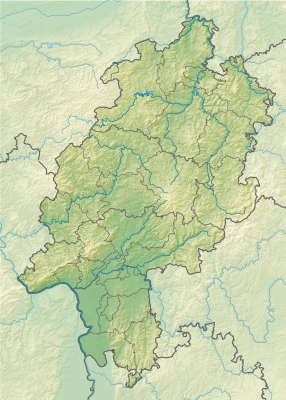

The castle ruins are located in the northern part of the Habichtswald Nature Park about 2.4 km north of Zierenberg on a western mountain spur ( 389.5 m above sea level ) of the Schartenberg ( 403.9 m ), between the valleys of the Nebelbeeke in the east and the warm one in the West.

history

A Saxon nobleman built, probably at the beginning of the 11th century, after the rule of the Konradines in Hessengau had come to an end, a castle on the Schartenberg, which is first mentioned in 1020, as being in the possession of a certain Anna. Around 1089 Volkold von Malsburg inherited the castle; it was first mentioned in 1062 and was named after its ancestral seat, the neighboring Malsburg castle . Volkold's sons Volkold II. And Udalrich brought the castles Malsburg and Schartenberg, inherited from their father, to the Archbishop of Mainz, Adalbert I, as a fief. Volkold II had already moved to Nidda before 1100 , where he followed his father as the Fulda bailiff of the Fulda Mark and founded the family of the Counts of Nidda from the Malsburg family.

Mainz enfeoffed the Counts of Dassel with Schartenberg Castle, where a castle man named Stephan (Stefan) was in office at the same time, a scion of a lower nobility and obviously a relative of the Mainz castle men who were also employed at the Malsburg. Stefan's descendants († around 1180?) Actually owned the castle until the end of the 14th century and therefore called themselves "von Schartenberg". The relatives on the Malsburg have called themselves von der Malsburg since at least 1143 . A smaller castle on the Schartenberg was given to the Groppe von Gudenberg as a fief.

At the beginning of the 13th century there was a bloody feud that lasted for years, probably triggered by inheritance disputes, within the von Schartenberg family, in which the other aristocratic families in the area were also involved. It was not until 1213 that the feudal lord, Archbishop Siegfried II of Mainz, managed to end the feud on a day of atonement in Fritzlar .

Albert von Schartenberg became known in the service of Bishop Simon von Paderborn , who bought the castle from Count Ludolf V. von Dassel in 1267 or 1268 . The Archbishop of Mainz, Werner von Eppstein, opposed this transfer of ownership of the Mainz feudal castle. An agreement was only reached in 1279: Archbishop Werner transferred one half of the castle as a fief to Simon's successor on the Paderborn bishop's chair, Otto von Rietberg , but kept the other half in Mainz ownership.

One of his successors, Archbishop Gerhard II von Eppstein , gave the Mainz half in 1294 as a fief and wedding gift to Elisabeth ("the middle one") (1276–1306), a daughter of Landgrave Heinrich I of Hesse , on the occasion of her marriage to Count Gerhard V. von Eppstein . The marriage remained childless and in 1307 this half fell to Landgrave Johann von Hessen , Elisabeth's brother , according to the contract . Johann died in 1311, and Archbishop Matthias von Buchegg demanded from Johann's half-brother and heir Otto I of Hesse, among other things, Schartenberg Castle as a reverted fief . This demand turned out to be insignificant, as Matthias suffered a devastating defeat in his long feud with Otto after initial military successes in 1328 near Wetzlar and had to give in to the mediation of King John of Bohemia .

After 1307 the castle was pledged for a long time to a Burgmann family from Hertingshausen, who then called themselves von Schartenberg. Known from this family was Stefan von Schartenberg, who, as the liege of Landgrave Heinrich the Iron, was involved in the breaking of the former Mainz Castle Haldessen near Grebenstein . He died childless around 1375. The last of this family, Hermann, a close relative of those of Malsburg and those of Dalwigk on the Schauenburg , sold his share in the castle to Landgrave Hermann II of Hesse and died in 1382 or 1383. Hesse then had both halves of the double castle to fiefdom, one half from Kurmainz, the other from Paderborn, but the Mainz archbishopric was no longer able to assert its fiefdom. The landgraves assigned the castle to their officials as a residence or pledged it with the court of the same name, among others to Reinhard IV von Dalwigk, Johann Spiegel , Dietrich von Schachten and Hermann von der Malsburg . The castle developed into the center of the office Schartenberg .

In the final phase of the fighting between the Archdiocese of Mainz and the Landgraviate of Hesse for supremacy in Lower and Upper Hesse , fighting broke out in advance of the castle. Led by Johann Spiegel, the then Mainz bailiff at the Schöneberg Castle near Hofgeismar , a bunch of Mainz feudal men and armed men from the Mainz city of Hofgeismar marched through the area of Grebenstein and the Diemel valley for several days in November 1424 . After that, the heap appeared at night in front of Schartenberg Castle, but the crew turned it away. Instead of the castle, the economic facilities and probably also the nearby village of Rangen were destroyed and the village of Fürstenwald was set on fire. This called Landgrave Ludwig I on the scene, who soon appeared before Hofgeismar, bombarded the city and in turn devastated the area.

Only three years later, in 1427, after Ludwig's decisive victories in the Mainz-Hessian War in July near Fritzlar and in August near Fulda against Archbishop Konrad von Mainz , Schartenberg Castle became Hessian.

The castle played a warlike role for the last time when the bailiff at the time, Heinrich von Boineburg, contributed twelve wagons to transport supplies to the landgrave's campaign against the Electoral Cologne town of Volkmarsen in 1476 .

The condition of the castle was no longer good, and in 1490 Landgrave Wilhelm I instructed the then pledge holder Dietrich von Schachten to have repairs carried out for 200 guilders. Whether this still happened is not known, but as early as 1518 the castle was described as abandoned and dilapidated. It was owned by the von der Malsburg in 1519/1521, but was left to decay. The ruin was unsuitable for use as a quarry, as the lime blocks broke into rubble when attempting to remove them. The destruction occurred through natural decay.

Description of the castle ruins

From the ruins Scharteberg standing at one of the steepest places on the western slope of the mountain saddle, which is keep as a single clearly visible relic. In summer it cannot be seen from the valley side, only in winter, when the surrounding trees have no leaves, can one guess its position. Access to the facility is free via a hiking trail; the keep is not accessible due to the risk of collapse.

The keep itself is round and relatively high and has a diameter of up to 8.5 m. At the western edge it collapsed about halfway on the weather side. There is no loose debris to be seen. The walls, which are up to 3 m wide at the base, taper significantly towards the top. At the end of the 19th century, a tunnel was broken into the base of the tower. This tunnel is narrow and also in danger of collapsing, it is closed by a gate. Inside the tunnel, supports and holes for beams and intermediate floors can be seen as remains of the fixtures. The broken points of the tower were overgrown for a long time. In the summer of 2006, extensive restoration work began on the main tower to secure the wall. The walls are made of locally available limestone , the color of which changes from fire red to creamy white.

The foot of the keep is the highest point of the complex. To the west is a step that is lined with only faintly recognizable and overgrown limestone wall remains. It should have formed the - or a (?) - castle courtyard. The original outer wall is only recognizable in parts that cannot be recognized from the inside. From the outside, that is, from below, since the mountain drops very steeply, they appear about one to two meters high in places.

To the north, a deep moat separates the keep part of the castle from the north part, the so-called Groppeschloss. To the northwest there are two terraces that are to be interpreted as parts of this castle. At its edge, the mountain drops steeply to the Warmetal. In this northern part of the castle only small remains of the wall are preserved, while the shape of the mountain shows clear traces of human formation.

literature

- Eduard Brauns: The Schartenberg ruins in the Warmetal. In: Hessischer Gebirgsbote. 66, 1965 (pp. 14-15).

- Rainer Decker: The history of the castles in the Warburg / Zierenberg area. Hofgeismar / Zierenberg 1989.

- Ernst Happel: Medieval fortifications in Niederhessen. Kassel 1902.

- Georg Landau : The Hessian knight castles and their owners. Four volumes, Bohné, Kassel 1832–1839. Facsimile reprint, Historische Edition Carl, Vellmar 2000.

- Wilhelm Chr. Lange: Schartenberg. In: Tourist reports from both Hessen, Nassau, Waldeck and the border areas. Frankfurt, December 1894, pp. 69-72 and January 1895, pp. 82-84.

- Rudolf Knappe: Medieval castles in Hesse: 800 castles, castle ruins and castle sites. 3rd edition, Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2000, ISBN 3-86134-228-6 , p. 34.

- Willi Vesper: Schartenberg Castle and its history. In: Homeland yearbook for the Hofgeismar district. 1952, pp. 75-78.

Web links

- Wilhelm Chr. Lange: Foreword / Overview , in The Schartenburg Project , on non-volio.de

- Part 1: Description of the castle , December 1894

- Part 2: History of the castle , January 1895

- Schartenburg (with Groppeschloß). Historical local dictionary for Hessen. In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

References and comments

- ↑ Map services of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation ( information )

- ↑ Hermann von Schartenberg received the landgrave-Hessian half of the Itter estate in 1376 in pledge possession. After his death this pledge came to Thile I. Wolff von Gudenberg .