Camera obscura

A camera obscura (lat. Camera "chamber"; obscura "dark") is a dark room with a hole in the wall, which is used as a metaphor for human perception and for the production of images. If the dark room is the size of a box, it is also called a pinhole camera .

While the technical principles of the pinhole camera were already known in antiquity, the use of the technical concept to produce images with a linear perspective in paintings, drawings, maps, architectural implementations and later also photographs was only introduced in the (or, see Erwin Panofsky , the) renaissance (s) of European art and the scientific revolution of modern times. Among other things, Leonardo da Vinci used the camera obscura as an image of the eye, René Descartes for the interplay of eye and consciousness and John Locke began to use the principle as a metaphor for human consciousness itself. This modern use of the camera obscura as an "epistemic machine" had important implications for the development of scientific thinking. Last but not least, Karl Marx's Dialectical Materialism and his famous claim to want to turn the Hegelian dialectic upside down (cf. Die deutsche Ideologie 1845-46) uses the optical effect as a central metaphor.

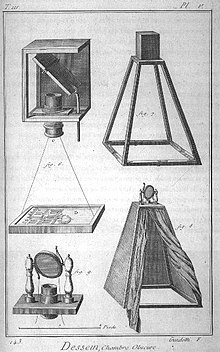

construction

A camera obscura consists of a light-tight box or room in which the light of an illuminated scene hits the opposite back wall through a narrow hole. On the back wall, an upside-down and reversed image of this scene is created. The image is faint and can only be seen well when it is sufficiently darkened. If the back wall is transparent, the picture can also be viewed from the outside if sufficient darkening is provided, for example by using an opaque cloth that covers the back of the back wall and the viewer's head.

functionality

If light falls through a converging lens or a small hole into an otherwise light-tight hollow body, a reversed and upside-down image , a projection of the outside space, is created in it. The diagram at the top right shows an example of two bundles of rays entering the hole from two points on an object. The small diameter of the diaphragm restricts the bundles to a small opening angle and prevents the light rays from completely overlapping. Rays from the upper area of an object fall on the lower edge of the projection surface, rays from the lower area are forwarded upwards. Each point of the object is shown as a disc on the projection surface. The superimposition of the slice images creates a distortion-free image. Expressed mathematically, the image is the result of a convolution of the ideal image of the object with the face of the screen.

Imaging geometry of a converging lens

Designated G , the article height (= actual size of the viewed object), g the object distance (= distance of the object from the lens), b (= distance from the image distance perforated disk for focusing screen) and B , the image height (height of the image formed on the Screen), then:

- (1)

Equation (1) is also known as the 1st lens equation from geometric optics. For mathematical derivation, reference is made to the theorem of rays in geometry. The image size only depends on the distances, but not on the aperture size or hole size.

history

The principle was already recognized by Aristotle (384–322 BC) in the 4th century BC. In the apocryphal writing Problemata physica , the creation of an upside-down image was described for the first time when light falls through a small hole into a dark room.

The Arab Alhazen made his first attempts with a pinhole camera around 980. He had already developed the optical effect and a seemingly modern theory of light refraction, but was not interested in the production of images of individuals. He also lived in a society that (see prohibition of images in Islam ) was hostile to image production . European artists and philosophers began to use Alhazen's technical knowledge in new frameworks with significantly expanded epistemic relevance.

From the end of the 13th century onwards, the camera obscura was used by astronomers to observe sunspots and solar eclipses so that they did not have to look into the bright light of the sun with the naked eye . Roger Bacon (1214–1292 or 1294) built the first apparatus in the form of a camera obscura for observing the sun.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) probably made similar attempts when using the central perspective.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) examined the beam path and found that this principle can be found in nature in the eye .

After lenses were ground in the Middle Ages , the small hole was replaced by a larger lens. This improved camera described in 1569 the Venetian Daniele Barbaro in his work La pratica della perspettiva and Giambattista della Porta (1563-1615) in his Magia Naturalis . Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) also seems to have known such a device .

In 1686 Johann Zahn constructed a portable camera obscura. A mirror, which was attached at an angle of 45 degrees to the optical axis of the lens inside the camera, reflected the image upwards onto a ground glass, which could be protected by a hinged cover during transport. The picture could easily be drawn from the screen. The image could be brought into focus through a rectangular extract. The camera obscura was often used as a drawing aid by painters before photography . One could paint the landscape on paper in it and reproduce all proportions correctly. The best-known example is the painter Canaletto with his famous paintings of Dresden and Warsaw . Johann Wolfgang von Goethe also used a device of the same design on his travels.

The Encyclopedia Britannica , published in 1929, already contained a large article on the camera obscura and quoted Leon Battista Alberti as the first documented user in 1437. At the beginning of the 19th century the camera lucida became increasingly popular and largely replaced the camera obscura as a drawing aid.

In 1826 Joseph Nicéphore Niépce succeeded in using a camera obscura in the heliography process to produce the first known and still preserved photograph La cour du domaine du Gras .

In 2001, the so-called Hockney-Falco thesis led to a scientific controversy about the camera obscura and the use of technological means in the Renaissance and the late Middle Ages in the USA. The painter David Hockney and the physicist Charles M. Falco claimed that they had demonstrated the use of technologically complex optical tools such as the camera obscura by the old masters and met resistance from art historians and physicists, who for various reasons considered this to be impossible. The hype surrounding the thesis ignored the thesis, which had already been solidified in the 19th century, of widespread use of the corresponding aids and the associated old scientific literature.

Well-known walk-in camerae obscurae

- Germany:

- Camera obscura with 3 viewing axes (horizontal) in the Limpsturm / light tower in Arnsberg in the Sauerland (opened August 10, 2012)

- Camera obscura (“Third Breath”) by James Turrell with a view of the sky in the Center for International Light Art in Unna .

- Camera obscura on the Oybin mountain near Zittau , built in 1852, renewed 1980–83, 360 ° panoramic view, specialty: the projection screen is the roof of a Trabant .

- Camera obscura in Hainichen near Freiberg , built in 1883, renovated in 1985

- Camera obscura in the Museum of the Prehistory of Film in Mülheim an der Ruhr 1992

- Camera obscura in the German Film Museum in Frankfurt am Main

- Camera obscura in Stade , Lower Saxony, built in 2008

- Camera obscura in Dresden in the Technical Collections Dresden

- Camera obscura in Ingolstadt (in the New Town Hall )

- Camera obscura in Biberach an der Riß in the Jordanbad (in the Sinnwelt )

- Camera obscura in Hamburg at the Altona balcony (with a view of the Köhlbrand Bridge Hamburg harbor )

- Camera obscura in Marburg , Hesse, built in 2002, in front of the Landgrafenschloss with a panoramic view of Marburg

- Camera obscura in Dennenlohe , Bavaria, built in 2006, in the Dennenlohe Castle Park with a panoramic view of the 16-hectare landscape park

- Camera obscura in Straubing , image of the area in front of the door of the city tower on the ceiling behind the door, laying of the foundation stone in 1316

- Austria:

- Camera obscura in Spitz , Lower Austria, on the Danube ferry / "Rollfähre" (art object by the Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson )

- Poland:

- Camera obscura in Bielawa Dolna ( Pieńsk municipality ) east of the Lusatian Neisse , built in 2017, part of the cross-border property ensemble The secret world of Turisede (formerly Kulturinsel Einsiedel , Zentendorf )

- Portugal:

- Spain:

- Camera obscura in Cádiz (in the Torre Tavira)

- Camera obscura in Jerez de la Frontera (in the Alcázar)

- Camera obscura in Tudela (in the Torre Monreal)

- Camera obscura in Seville (in the Torre de los Perdigones)

- Hungary:

- United Kingdom:

- Camera obscura in Edinburgh , Dumfries , Bristol , Greenwich (London) and Aberystwyth in the UK

- United States:

- Camera obscura in San Francisco

- Other countries:

- Camera obscura in Biel , Switzerland (as part of the Cinécollection Piasio in the Museum Neuhaus )

- Camera obscura in Moscow's Lomonosov University

- Camera obscura building in Aegina in Greece , built 2003, 360 ° panoramic view *

- Camera obscura in Makhanda , South Africa

- Camera obscura in Havana , Cuba (at Plaza Vieja)

- Camera obscura in Hampi , Karnataka, India ( Virupaksha Temple).

literature

German speaking

- Olaf Breidbach , Kerrin Klinger, Matthias Müller: Camera Obscura. The darkroom in its historical development . Stuttgart, Franz Steiner, 2013, ISBN 978-3-515-10005-2

- Franz Daxecker : Christoph Scheiner and the camera obscura . In: Acta Historica Astronomiae 28, contributions to the history of astronomy, Vol. 8 (2006), pp. 37-42

- Bodo von Dewitz, Werner Nekes (ed.): I see something that you don't see - viewing machines and worlds of images . Steidl, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-88243-856-8

- Willem Jacob's Gravesande: Using the Dark Chamber for Drawing . In: Sarah Kofman: Camera obscura. From ideology . Edited and translated from French by Marco Gutjahr. Turia + Kant, Vienna / Berlin, 2014, ISBN 978-3-85132-744-1 , pp. 91–123.

- Fritz Hansen : Chronica of the camera obscura . Berlin 1933

- Tobias Kaufhold : Camera Obscura: Museum of the prehistory of film . Klartext, Essen 2006, ISBN 3-89861-661-4

- David Knowles: The Secrets of the Camera Obscura. Novel . Heyne, Munich, 1996, ISBN 3-453-10838-8

- Jens Lohwieser, Marcus Kaiser : + partly garden - the city in the hut. Camera obscura installation on the grounds of the Nordbahnhof in Berlin . Ernst Moritz Arndt University of Greifswald, ISBN 3-86006-228-X

- Karen Stuke: “The trilogy of the good times, or: I don't mind waiting!” Camera obscura photography . Texts by Andreas Beaugrand and Gottfried Jäger. Edition Beaugrand Kulturkonzepte at Verlag für Druckgrafik Hans Gieselmann, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-923830-63-3

- Burkhard Walther, Przemek Zajfert: Camera Obscura Heidelberg . Black and white photographs and texts. Historical and contemporary texts . edition merid, Stuttgart, 2006, ISBN 3-9810820-0-1

English speaking

- Marcus Kaiser: Wall Views - The Monument as Medium extra verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-938370-38-4

- Hans Knuchel: Camera Obscura Lars Mueller Edition, Baden 1992, ISBN 3-906700-49-6

- Eric Renner: Pinhole Photography: Rediscovering a Historic Technique , (Second edition, 1999), Focal Press, Butterworth-Heinemann, Newton, MA, USA ISBN 0-240-80350-7

- Jim Shull: The Hole Thing. A Manual of Pinhole Photography , Morgan & Morgan, Inc., New York 1974, ISBN 0-87100-047-4

- Lauren Smith: The Visionary Pinhole , Gibbs M. Smith, Inc., Peregrine Smith Books, Salt Lake City, 1985, ISBN 0-87905-206-6

- Philip Steadman: Vermeer's Camera , Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-19-280302-6

- Adam Fuss: Pinhole Photographs (Smithsonian Photographers at Work), Smithsonian Institution Press ISBN 1-56098-622-0

- Thomas Harding: One Room Schoolhouses of Arkansas as Seen through a Pinhole , University of Arkansas Press, ISBN 1-55728-271-4 , ISBN 1-55728-272-2

- Eric Renner, Center For Contemporary Arts Staff (Editor): International Pinhole Photography Exhibition, Center for Contemporary Arts of Santa Fe , ISBN 0-929762-01-0

- Lauren Smith, Pinhole Vision I and II , LBS Produc ISBN 0-9607796-0-4

- Ype Limburg: Camera Obscura Fotografie-Gallery Rhomberg Innsbruck Austria 2011–28 cm × 29 cm Hardcover-thread bond-64 Pages-Text Dr. Veronika Berti-German and English- ISBN 978-3-200-02128-0

Web links

- Tilman piece: A short history of the pinhole camera or camera obscura

- Worldwide Pinhole Photography Day

- Net art project Camera Obscura 2005/1-∞

- Dieter's Pinhole Camera Page - Comprehensive information on pinhole cameras, with FAQ, assembly instructions and mailing list; by Dieter Bublitz (†)

- Detailed explanation of how a camera obscura works in the form of a comic ( memento from November 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

Footnotes and individual references

- ^ Philosophy of Technology: Practical, Historical and Other Dimensions PT Durbin Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Contesting Visibility: Photographic Practices on the East African Coast Heike Behrend transcript, 2014.

- ↑ Don Ihde Art Precedes Science: or Did the Camera Obscura Invent Modern Science? In Instruments in Art and Science: On the Architectonics of Cultural Boundaries in the 17th Century Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, Jan Lazardzig, Walter de Gruyter, 2008.

- ^ Merleau-Ponty and Epistemology Engines, by Don Ihde and Evan Sellinger, Human Studies 27: 361-376, 2004. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

- ^ Terence Wright: Visual Impact: Culture and the Meaning of Images. Oxford, New York 2008, p. 16 ; the problemata physica is pseudo-Aristotelian ; see also Thomas Rakoczy: Evil Eye, Power of the Eye and Envy of the Gods: an investigation into the power of the look in Greek literature. Volume 13 of Classica Monacensia, Tübingen 1996, p. 141 and The Problemata Physica, attributed to Aristotle. Brill, accessed February 19, 2014 .

- ↑ Hans Belting The real picture. Image questions as questions of faith. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53460-0 .

- ↑ An Anthropological Trompe L'Oeil for a Common World: An Essay on the Economy of Knowledge, Alberto Corsin Jimenez, Berghahn Books, June 15, 2013.

- ^ Daniel Köhne: Short story of seeing , project Blickkulturen 2008/09; Robert D. Huerta: Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: the Parallel Search for Knowledge During the Age of Discovery. 2003, p. 127, note 54 (English).

- ^ Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: the Parallel Search for Knowledge During the Age of Discovery. , 2003, p. 43, (English).

- ↑ a b c d Don Ihde, Art Precedes Science: or Did the Camera Obscura Invent Modern Science ?, in Schramm, Schwarte, Lazardzig (Ed.): Instruments in Art and Science: On the Architectonics of Cultural Boundaries in the 17th Century, 2008 Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-020240-3 , pp. 384-393.

- ^ The camera obscura in Hainichen. Heimatverein Striegistal, accessed on March 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Thorsten Penz: Camera Obscura in Stade is on hold. In: Kreiszeitung Wochenblatt. October 17, 2018, accessed March 18, 2020 .

- ^ Dorle Knapp-Klatsch: Lahntal: Camera obscura in Marburg. September 19, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018 .

- ^ Steffen Gerhardt: A new adventure village on the Polish side. In: Saxon newspaper . June 22, 2018, accessed March 18, 2020 .