Music for violoncello

In this article, the development of music with the solo violoncello is examined chronologically. A fundamental distinction is to be made between solo cello music, in which the cello is accompanied as a soloist by one or more instruments (up to a full orchestra), and literature for cello alone, which is written for a single cello without any accompaniment.

17th and 18th centuries

The beginnings in Italy

The first works to use the violoncello as a solo instrument are the sonata a due ea tre con la parte di violoncello a beneplacito op.4 by Giulio Cesare Arresti . A number of solo pieces followed at the end of the 17th century . Often these compositions are not yet written for our current mood (C, G, D, A) and are therefore not easily playable on every violoncello today.

One of the first composers who wrote for the cello, include yourself as cellist in Bologna working Giovanni Battista degli Antonii (1687), Domenico Gabrielli (1689), Domenico Galli (1691), Giuseppe Maria Jacchini (1692) and Antonio Maria Bononcini ( 1693). Even these early compositions were technically demanding and placed high demands on the musician. Of these works, Gabrielli's two sonatas (1689) and those by Jacchini and Bononcini are the earliest works for the violoncello accompanied by figured bass .

Diffusion and development

The steady development of cello playing with its initially almost exclusive centering on Italy gave rise to a large number of solo works with figured bass from the end of the 17th century. As in Bologna, most of the sonatas were written by cellists themselves. The level of the sonatas is very different. It ranges from the baroque "dozen items" to virtuoso compositions with sophisticated melodic and rhythmic structures, with the affect language gained from the opera also making its way.

New technical means that became standard in the course of the 18th century include: a. Thumb attachment (first mentioned in 1741 by Michel Corrette ), scale steps , arpeggios and double stops , as well as less common flageolet tones and strings jumping figures. These technical innovations can sometimes also be seen in the works of Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). Today we have ten cello sonatas and a number of cello concertos by the Italian. Also, Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) are due three sonatas for cello.

Outside Italy

In the first half of the 18th century, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767) was the first to be mentioned outside of Italy . He wrote a virtuoso and multifaceted sonata in D major. The beginning cello player is also familiar with Joseph Bodin de Boismortier and Willem de Fesch from this period thanks to the numerous easy-to-play duets and sonatas .

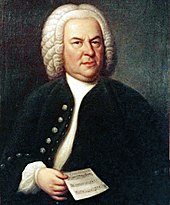

The great popularity of the Six Suites for Solo Cello by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) is due to the rediscovery and the first significant interpretation by Pablo Casals at the beginning of the 20th century. These graceful and balanced compositions are of highly developed compositional and compositional skill (real and latent polyphony ). The original manuscript and date of creation are still unknown, but the work survived through many copies such as that of Anna Magdalena Bach . The Six Suites are among the most famous virtuoso compositions for violoncello today and are accordingly often played.

Development of the violoncello concerto

One of the first composers who wrote concert-like pieces for the cello was Antonio Vivaldi, who not only had a strong influence on the development of the cello concertos, but also that of the instrumental concert in general. He has received 27 cello concertos, most of which date from the 1720s. Largely introduced by Vivaldi and further developed features of the concertos as a common method are the three movements (fast-slow-fast) and the ritornello form - those mainly for the first, but also the third movement. The 28 cello concertos by Giovanni Benedetto Platti , which were also composed in the mid-1720s, play a similar role .

The second half of the 18th century

Among the sonatas with basso continuo composed in the second half of the 18th century, the works of Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) are the first to be emphasized. The more than 40 sonatas were mainly intended for his own concert evenings. This also applies to most of the other composers from the first half of the 18th century, so that they were often unable to achieve greater and longer-term awareness. However, the second half of the 18th century also included the cello concertos by Joseph Haydn (e.g. No. 1 in C major, No. 2 in D major, No. 3 in C major (considered lost), No. 4 in D major , No. 5 in C major, Concerto in G minor (lost)).

Among the cello concerts by Italian musicians from the last third of the 18th century (including Giovanni Battista Cirri , Luigi Borghi , Domenico Lanzetti ), those by Luigi Boccherini occupy a special position because of their melodic brilliance and their technical brilliance. They demand a great deal of security from the player in the long passages, which can be played virtuously in high registers. A total of twelve cello concertos by Boccherini are known. In the form of three movements, the concerts vary from a style characterized by baroque elements to the Viennese classic , but remain much simpler in terms of harmony. Boccherini's works range from pure string concerts to string and wind instrumentation.

Cello literature in France and Great Britain

The French cello literature of the late 18th century includes compositions by Martin Berteau , Jean-Balthasar Tricklir , Jean-Baptiste Janson and Jean-Louis Duport, as well as the A major concerto by Jean-Pierre Duport . Also known are some of the seven cello concertos by Jean-Baptiste Bréval , who, in addition to simple pieces, often composed works with some technical difficulties.

Among the British composers in the latter half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries are Joseph Reinagle , John Garth and Robert Lindley .

19th century

First classical sonatas

The sonata type for a melody instrument and piano, which we now call "classical", was not developed until 1775 after the period of the figured bass. This new form was mainly started by Ludwig van Beethoven . Following the example of his sonatas for piano and violoncello, which represented an important form of design, composers created over 150 sonatas in the 19th and first half of the 20th century.

In any case, the sonata in A minor by Franz Schubert , which was originally written for Arpeggione , is an integral part of cello literature, which is characterized by its catchy themes . Since this instrument (similar in structure to the guitar , playing roughly the same as the cello) was only granted a short existence, some violists and cellists later took it on and thus saved it from destruction. It turned out, however, that the technical requirements on the violoncello are extremely high.

The two sonatas for violoncello and piano (E minor op. 38, F major op. 99) by Johannes Brahms are also very popular .

1st Concerto pour Violoncelle by Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921) also wrote two violoncello sonatas. His 1st Concerto pour Violoncelle, Op. 33 in A minor , is certainly better known . The concert is a very classical, three-movement work ( Allegro non troppo - Allegretto con moto - Un peu moins vite), which was composed in 1872. At first glance, this concerto seems to be composed in one movement, although the internal structure shows up in three movements. After a double exposure, there follows a very classic, minuet-like middle section. With two new topics , the finale then goes smoothly. The short, apparently simple opening theme runs through the entire twenty-minute concert, mostly with only the first six notes, and turns it into a complete work. After a short tutti strike by the orchestra , the solo violoncello sets in with its falling triplets . The Allegro non troppo is then repeatedly interspersed with this opening theme. The short theme gets its character from the very fast and often repeated downward triplet runs. In a striking “ Poco animato ” a lively ascent begins, which is caught in a rallentando and now leaves the orchestra to lead. The theme is repeated in different versions. In an energetic, chromatic rise, everything gathers to an absolute climax, but shortly before it thinks about it and turns into soulful melancholy . After a strong crescendo and a short accelerando , a two-part “animato” begins. Similar to a cadenza , the whole thing ends in an “Allegro molto”. Although written after the Classical era, this piece still reflects the full splendor of this period.

The not so well-known Saint-Saëns' second violoncello concerto ( 2nd Concerto pour Violoncelle op.119 in D minor), which is composed of two movements, is similarly imaginative in its formal design .

Difficulties in establishing the violoncello concerto

Only a few cello concerts outside of virtuoso literature succeeded in gaining an undisputed place in the cello literature, similar to the Saint-Saëns Concerto. The small number of successful violoncello composers also includes Robert Schumann , Pjotr Iljitsch Tchaikovsky , Antonín Dvořák and, to a lesser extent , Édouard Lalo , Eugen d'Albert and Max Bruch . This also shows that a majority of the important composers of the 19th century did not turn to the cello as a concert instrument. There is no clear explanation for this. But it could certainly be related to the fact that even after the middle of the century the cello was far less in the foreground of general musical interest than the piano or the violin, for example.

One obstacle may have been the composers' insecurities about writing for an instrument whose playing technique and sound they did not know well enough. Which makes, for example, a letter from Johannes Brahms after completing his double concerto for violin and cello to Clara Schumann clear:

I should have ceded the idea to someone who knows the violin better than I do ... It's something different to write for instruments whose type and sound you only have in your head in passing, which you only hear in your mind - or for an instrument write that you know through and through, like I know the piano, where I know what I'm writing and why I write and write like this ...

In conclusion, one can assume that Schumann, Tschaikowsky and Dvořák had similar reasons to seek advice from cellists who were friends.

Composer for violoncello in the 19th century

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann's Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 129 , the first important composition of this genre, was written in Düsseldorf in October 1850 . Schumann worked out the technical design of the solo part with the cellist Robert Emil Bockmühl , who stood by his side as a correspondent. What is striking about the structure of the work is that although it is in the classic three-movement form, the movements flow into one another without a break.

Robert Volkmann

The most important violoncello concerto by a German composer between Schumann and Brahms is the Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 33 by Robert Volkmann , which was written between 1853 and 1855. Like the first Saint Saëns Concerto, it is in one movement, but it does not combine three individual movements like this one, but unfolds as a large sonata movement.

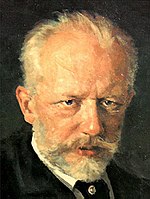

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

In 1876/1877, Pjotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's pen wrote Variations in A major for violoncello and orchestra on a Rococo theme, Op. 33 . The demanding solo part was arranged by Wilhelm Fitzenhagen , who also took over the solo part at the premiere in Moscow. In a piano reduction, Fitzenhagen thoroughly revised the parts and finally came from the original eight variations to his version with seven variations.

Edouard Lalo

In 1877, Édouard Lalo composed his Cello Concerto in D minor, which was very much focused on the lower sound range of the cello . The technical fingering requirements correspond roughly to the Saint-Saëns concert.

Max break

Max Bruch's two-part concert piece Kol Nidrei op.47 from 1880/1881 is based on an old Hebrew melody in the first part, after which the work is named. This melody is one of the most important Jewish chants. The second part is determined by a Brahms-based melody in D major.

Antonín Dvořák

After a first attempt at a violoncello concerto in 1865 stopped at the draft stage, Antonín Dvořák wrote the glamorous Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in B minor op.104 ( New York late 1894, early 1895) during the last two years of his stay in America . The piece is dedicated to Hanuš Wihan , which was originally supposed to play the world premiere, but after too many unauthorized changes in the solo part fell out with the composer so that the English cellist Leo Stern played the world premiere in London.

Johannes Brahms

The aforementioned double concerto for violin and cello in A minor by Johannes Brahms was written in 1887 in Hofstetten on Lake Thun . Brahms' main problem with the concert was not playability, but the harmony of violin and cello. In this unusual project, Brahms feared that the violin, with its brilliant sound, could outdo the violoncello. Where he worked firstly by octave and very effective duplication to vote against, on the other hand the cello in all three sets has been assigned the lead role.

20th century

However, it was only in the twentieth century that the violoncello achieved its really appropriate importance as a soloist. Many compositions, which encompass the violoncello in all its diversity, were inspired by the great virtuosos of this century and are dedicated to them. Above all Pablo Casals and Mstislaw Rostropowitsch (Prokofiev's Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 58 ) should be mentioned.

Technical innovations and experiments

In the 20th century, classical music was subject to constant change and experimentation to a greater extent than in previous epochs. This is not least due to the industrial and technical revolution and the associated new developments and new discoveries. Music could now be stored on sound carriers, electronically changed and edited. In the 20th century, for example, composers deal with the cello in connection with electronics and tape , but also with electrically amplified cellos and similar innovations. Foreign cultures and styles of music met and mingled more than ever. The entertainment market was increasingly no longer determined by the regional environment, but increasingly international, which was expressed in radio and television. The cello itself, however, hardly changed compared to the form established by Stradivarius .

The compositions for violoncello in the 20th century are categorically difficult to grasp, since the new stands next to the old. For example, Sergei Rachmaninoff still represents the style of the 19th century in his Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G minor, Op . 19 (1901). The development of the instrument seems to be gaining enormous popularity in the 20th century and it is hardly inferior to the violin , which also includes the exponentially increased production of études in the 20th century ( e.g. the high school of David Popper ).

Cello composers in the 20th century

Max Reger

Against the downward trend in this genre, Max Reger wrote three suites for solo cello in G major, D minor and A minor in 1915 . In addition to works for violin and solo viola, these suites represent for him an intensive examination of Bach's solo works. Reger's late Romantic works, with those of Zoltán Kodálys, set a new starting point for cello compositions in the last century .

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály's 30-minute solo sonata was written in the same year that Reger's suites were created. This mentality is very much influenced by Hungarian folk music , which was not least rediscovered by Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály.

Nadia Boulanger

Also in France in 1915 were the two (unnamed) pieces for violoncello and piano (E flat minor and C sharp minor) by Nadia Boulanger , three years later her Lux aeterna (1918) for voice, harp, violin and violoncello. Nadia Boulanger was one of the most important composers, music teachers and conductors in France and the USA. During her lifetime she kept the memory of her sister Lili Boulanger alive, and she dedicated her life entirely to the service of music. Thanks to Nadia's work and passion, so-called early music in particular flourished again in France by bringing the works of old masters to the stage for the first time. Her students were among others Astor Piazzolla , Daniel Barenboim and Marion Bauer . After long oblivion, Nadia Boulanger's works for cello are increasingly being played in concert halls around the world and are increasingly becoming part of the standard repertoire.

Lili Boulanger

Like her sister Nadia, Lili Boulanger was one of the most important composers in the world at that time - and still is today. As the first woman in history, she won the Prix de Rome with incredible ease with her sensational cantata Faust et Hélène (1913). Very limited by her severe physical illness, Lili Boulanger always composed knowing that she would die early. Shortly before her death in 1918, Lili composed the extraordinarily impressive Pie Jesu for voice, harp, organ and string quartet with the last of her strength . With the piece Lux aeterna , her sister Nadia created a musical monument for her - by using her sister's favorite instruments in this composition and thus relating both works to one another. Lili's oeuvre was forgotten soon after Lili's death, despite Nadia's efforts. While Nadia's music sounds more well-founded and romantic, Lili's music is almost sphereless and impressionistic, but never becomes atonal.

Joaquín Rodrigo

His classic three-movement cello concerto “Concierto en modo galante”, written in 1949 for the cellist Gaspar Cassadó, and the one-movement “Concierto como un divertimento” from 1981, were written by the Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo .

Paul Hindemith

A departure from the romantic was represented in an even clearer language by Paul Hindemith in his sonata for violoncello solo, which in terms of art-aesthetic architecture has its equivalent in the Bauhaus style . The work is characterized by sequences of dissonances, e.g. B. parallel sevenths . The music leaves romanticism and turns to new sound experiences, which were continued by other composers in the decades that followed.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakowitsch wrote two cello concertos, both of which are dedicated to Mstislav Rostropowitsch: His Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat major op. 107 from 1959 is now in the standard repertoire and has been made in numerous recordings. The extraordinary thing about this work is the four-movement structure, whereby the third movement is a 150 bars long solo cadenza. The 2nd violoncello concerto in G major op. 126 from 1966 is already one of the composer's late works.

Toshiro Mayuzumi's Bunraku

The cello repertoire of Toshiro Mayuzumi's Bunraku was enriched with strange sounds from Japan . He tried to transfer the Japanese Shamisen to the violoncello (Shamisen are three-string Japanese plucked instruments ). As already mentioned, attempts were made in the course of the 20th century to transfer music from different cultures to the cello.

Isang Yun

In Glissées for solo violoncello (1970) - four studies that are formally closely related to one another - Isang Yun addressed the possibility of a smooth transition, the glissando. Inspired by the sound characters of the Korean stringed instruments, especially the two-string fidel haegŭm and the six-string zither kŏmun'go , Yun developed and noted (based on the twelve-tone technique, the experience of the sonic continuity of electronic music and the traditional music of his homeland) one in the Western European art music with novel idioms. Each of the pieces, in which characteristic playing techniques emerge, has an arch-shaped structure and is continued in the following. The late cycle of the Seven Etudes for Solo Cello (1993) is also dominated by a dramaturgy of intensification . In them, particular technical difficulties are discussed, but also compositional issues: Legato - Leggiero - Parlando - Burlesque - Dolce - Trill - Double stops . One of the most important cello concertos of the 20th century is that of Isang Yun (1975/76, with autobiographical references, including his imprisonment in South Korea 1967-69).

Iannis Xenakis

Iannis Xenakis ' piece nomos alpha (1965), which dispenses with conventional playing techniques and thus also with the typical cello sound, is quite abstract . The piece was composed using mathematical theories or a computer program . For the implementation of the piece, equipped with all imaginable technical refinements, certain gut strings are required in certain tunings.

Bernd Alois Zimmermann

Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Four Short Studies (1970) were written for the cellist Siegfried Palm as a contribution to his anthology Pro musica nova. Studies in Playing New Music . In terms of instrumentation, they should also serve as a preparation for Zimmermann's extremely demanding Sonata for Cello Solo (1960). The first of the four studies shows a compositional technique that Zimmermann originally called “pluralistic” (a term that was understood or interpreted differently for a young poet under the impression of his musical theater The Soldiers or the Requiem ): He layers “two different courses of time one on top of the other, which can be distinguished from one another by different tone colors and line types. The second study focuses on the differentiated pizzicato game with different contact points on firmly gripped and flageolet points. The third deals with the problem of the rapid change between one-part repetitions and playing with several voices - mostly in the symmetrical structure characterized by quintuplets, as is often found in Zimmermann's. Finally, the fourth study practices cantable playing at extreme heights: practice material is offered here for the final movement versetto of the solo sonata as well as for some sections of the Canto di speranza . "(Wulf Konold)

Newer playing techniques

In his piece Pression for a cellist from 1970, Helmut Lachenmann developed several new (though not all of the below) playing techniques. The goal was to enrich the tonal palette of the cello (or more generally: the strings) - a goal that the composers of this time as a whole had in mind. Recent developments include:

- unusual leaps in intervals

- Playing cantiles in very high registers

- Double fingerings (with a firmly gripped tone and a flageolet tone ); Double handles in the flageolet

- Flageolet arpeggios

- Glissando with vibrato ; Glissando with trills and tremolo

- Double glisando (glissando on two strings)

- Flageolet Glisando; Flageolet glissando in tremolo

- Vibrato at different speeds

- various pizzicato and tapping rules for the left hand:

- Dab the string

- Strike the string with one finger

- tap the string with your fingers

- Hit the strings with the flat of your hand

- Pull your fingers off the strings (left hand pizzicato)

- Pluck the strings in the pegbox

- Different pizzicato rules for both hands:

- right hand plucks on the fingerboard (sul tasto) or on the bridge (sul ponticello)

- arpeggiando (pizzicato in arpeggio style )

- alla chitarra (guitar-like, with fingers (thumb), fingernails or plectrum )

- alla mandolino (quick back and forth movement with two fingers between two strings)

- Balalaika effect (rub back and forth on the string with your right thumb or pick on the side of the string)

- Bartók pizzicato

- Pizzicato with your fingernail

- Let the string snap against a fingernail of the left hand

- Glissando -Pizzicato (single notes and chords)

- Flageolet pizzicato

- Pizzicato fluido (pizzicato with the left hand, then press the bow tensioning screw against the corresponding string)

- Pizzicato with both hands at the same time (pizzicato of a string in the pegbox with the left hand, pizzicato of an empty string in front of or behind the bridge with the right hand)

- Scordatur (retuning strings)

- Combination and very quick change of different line types

- strike three strings at the same time

- Paint the string (s) from below

- play on the jetty (sul ponticello)

- play on the fingerboard (sul tasto), seamless transition of both playing styles

- play behind the bridge (dietro il ponticello), stroke with great pressure behind the bridge

- stroke with the bow pole ( col legno tratto)

- Saltando with the bow pole

- Glissando by moving the bow rod vertically

- paint with bow hair and bow stick at the same time

- Tremolo with the bow bar almost on the bridge and bow hair behind the bridge

- stroke on the tailpiece; apply pressure to the tailpiece (foghorn effect)

- stroke on the sting (gentle rustling)

- hit the strings with the bow stick ( col legno battuto)

- tap the frame or ceiling with the fingers of your left hand

- hit the body with the palm of your hand

- Strike the strings, the body or the sides with both flat hands

- drum your fingers on the top or the frame

- Hit the tailpiece (bongo effect), the frame or the top with a mallet

Other composers

Ernst Krenek went innovative ways with his Suite for Violoncello Solo op.84 from 1939 in the twelve-tone composition . Hans Werner Henze also uses the twelve-tone technique in his Serenade for solo cello, written in 1949, but is very idiosyncratic with the series technique.

Benjamin Britten's three solo suites (op. 72, 1964; op. 80, 1967; op. 87, 1971) fall back on baroque types of movements with neoclassical stylistic devices, the third on folk songs based on Tchaikovsky, which are connected with each other in the form of variations. They are dedicated to Mstislav Rostropowitsch, who also premiered them.

Zoltán Kodály's two-movement sonata for violoncello and piano op.4 from 1910 shows an expressive approach to Hungarian folk music. Béla Bartók's rhapsodies for violin and piano are close to Romanian folk music , of which he wrote a version for violoncello and piano for the first; his Sonata for Cello alone op.8 from 1915 is one of the most exposed pieces of this genre. The turning away from late Romantic compositional practices can be observed in Anton Webern and Claude Debussy , whereas Webern's Three Little Pieces op. 11 (1914) are more of a radical break than a turning away. “I clearly had the idea of a larger, two-movement composition for violoncello and piano and immediately began to work. But when I held a short piece in the first sentence, it became increasingly clear to me that I had to write something else. So I broke off, although that larger work had gone off well, and quickly wrote the little pieces (that is, I had the first one before and another, which I rejected), and that's how these three things came about. And I've rarely had the feeling that something has turned out good. ”Claude Debussy's Sonata for Cello and Piano (1915) has been an integral part of cello literature for decades. The piece is characterized by consistent motivic references and playful, virtuoso elegance.

Still be Gabriel Fauré's cello sonatas, neglected because of their certain brittle, which is typical in the late works by Fauré. Paul Hindemith often occupied himself with piano-accompanied violoncello compositions in his oeuvre. His spectrum ranges from English children's songs to compositions from the tradition of the 19th century, to extremely dissonant works, which, like the Sonata for Cello alone op.25.3 (1922), can be based on folk songs. Kurt Weill's early work also includes a three-movement work rich in expressive possibilities.

The second of Bohuslav Martinů's three sonatas captivates through the pronounced equal treatment of cello and piano . Interesting rhythmic experiments can be found in the cello works by Elliott Carter .

Wolfgang Fortner is not subject to any neoclassical influences: his works are based on mosaic-like, high-contrast compositions and temporary twelve-tone compositional tricks. The extent to which Sergei Prokofiev was appropriately influenced by the communist party after his voluntary return to the Soviet Union can only be largely speculated, but conservative elements cannot be overlooked in his works. In Benjamin Britten's piano-accompanied violoncellow works, both sonata and suite forms unite. An enormous leap, however, can be observed between Britten's Sonata in C major op.65 (1961) and the composition Intercommunicazione per Violoncelle e pianoforte (1967) by Bernd Alois Zimmermann , composed six years later . With this piece, Zimmermann consistently pursues the idea of stretching time. The tone lengths are graphically indicated here by dots and lines.

Concert works are introduced in the 20th century by Alexander Glasunov's short work "Chant du ménestrel" in 1900. Concerts for violoncello and orchestra by Ernst von Dohnányi , Paul Hindemith, Edward Elgar (whose cello concerto was written in 1919) and Frederick Delius are also still rooted in the late Romantic period . Ernest Bloch did not endeavor to innovate in his “ Schelomo ”, but tried to compose specifically Jewish music on the violoncello. Arthur Honegger's (1892–1955) violoncello concerto is based on American pop and dance music. Arnold Schönberg adapted a cello concerto by Matthias Georg Monn in D major (1764) on behalf of Pablo Casals in 1932 , but it did not really catch on. Sergei Prokofiev also had a hard time with concerts for cello and orchestra , whose Cello Concerto in E minor op. 58 was a failure, while his second, premiered by Rostropovich, caused him to make constant changes. The composers Alberto Ginastera , Günter Kochan and Heinrich Sutermeister each wrote two violoncello concertos. In his Sonata for Violoncello and Orchestra (1964), Krzysztof Penderecki goes beyond the twelve-tone series to the quarter-tone technique. Also Gyorgy Ligeti wrote in 1966 a tone composition for cello and orchestra. Witold Lutosławski wrote one of the most effective contemporary compositions for cello and orchestra .

As mentioned, pieces for violoncello and tape, violoncello and live electronics , violoncello and percussion, as well as for violoncello or violoncello in combination with a human voice, such as B. Hans Werner Henze's cantata Being Beauteous for coloratura soprano , harp and four cellos from 1963 and the requiem “Wolkenlos Christfest” for baritone, cello and orchestra by Aribert Reimann .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marc Vanscheeuwijck: The Cappella Musicale of San Petronio in Bologna under Giovanni Paolo Colonna (1674-95): history, organization, repertoire publisher Brepols, 2003 Publisher: Institut historique belge de Rome, ISBN 90-7446-152-2

- ↑ Marc Vanscheeuwijck: Ricercate sopra il violoncello ... preface to the new edition, Arnaldo Forni Editore, Bologna 2007, ISBN 978-8-8271-3008-7

- ↑ Marc Vanscheeuwijck: Ricercari per violoncello solo ... preface to the new edition, Arnaldo Forni Editore, Bologna 2004, ISBN 978-88-271-2890-9

- ↑ Stephen Bonta: From Violone to Violoncello: A Question of Strings? Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society 3 (1977), p. 13 ff.