Edvard Beneš

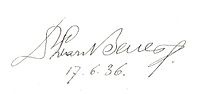

Edvard Beneš [ ˈɛdvart ˈbɛn anhören ] (* May 28, 1884 in Kožlany , then crown land of Bohemia , Austria-Hungary ; † September 3, 1948 in Sezimovo Ústí ) was a Czechoslovak politician ( ČSNS ), one of the founders of Czechoslovakia and Czechoslovak Foreign Minister (1918-1935), Prime Minister (1921–1922) and State President (1935–1938 and 1945–1948 and 1940–1945 as self-appointed President in exile).

youth

Edvard Beneš was the tenth child of a small farmer and was baptized Eduard (called "Edek" as a child), later he changed his name to Edvard. After studying in Prague and France ( Paris and Dijon ), Beneš first worked as a professor of sociology at the Charles University in Prague .

Political activity during the First World War

During the First World War , Beneš and others founded the Czech anti- Austrian resistance organization Maffie . From 1915 he campaigned (together with Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and the Slovak Milan Rastislav Štefánik ) from Paris for Czech and Slovak national endeavors: He gave lectures on Slavism at the Sorbonne and was co-founder and general secretary of the Czechoslovak National Committee founded in 1916 ( initially briefly called "Czech National Council"). In 1916 he published the manifesto "Détruisez l'Autriche-Hongrie" in Paris , in which he called for the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy .

With his commitment to the Czech cause, he and others obtained the establishment of the Czechoslovak legions in the spring of 1917 . They achieved that the Czechoslovak National Council was recognized by France in 1918 as the sole representative of the planned Czechoslovak state and was given a right to a say in the negotiations on the Treaty of Versailles .

Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia (1918 to 1935)

From 1918 to 1935 Beneš was foreign minister of the Czechoslovak Republic under President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk , and in 1935 he became his successor. 1921–1922 he was also head of government.

Politically, he was at home in the Czechoslovak People's Socialist Party ( Československá strana národně socialistická , or ČSNS for short ), of which he was deputy chairman until 1935. He joined this party more or less involuntarily, as the 1923 cabinet only tolerated him as foreign minister if he formally gave up his political independence and joined one of the parliamentary parties. It still exists today and at no time had any connection to German National Socialism .

With regard to Czech-Slovak relations, he was one of the leading proponents of Czechoslovakism . So he declared in 1943 in exile in London:

“I firmly believe that the Slovaks are Czechs and that the Slovak language is a dialect of the Czech language, just as it is with Hanak or other dialects of the Czech language. I do not prevent anyone from saying that they are Slovak, but I will never allow the declaration that there is a Slovak nation. "

Beneš was against the communist October Revolution in Russia in 1917 and, as foreign minister, oriented Czechoslovak politics in a more anti-Soviet and neo-Slavic manner . However, he was aware of the need for cooperation with the Soviet Union . In 1931, on his initiative, the "Danube Plan", a customs agreement that provided for the export of agricultural goods from the Balkans and the import of industrial goods from the Western powers, was launched. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 , Czechoslovakia recognized the USSR de jure as a state on June 9, 1934, under the leadership of Beneš (and with the consent of France ) and signed a friendship treaty with it in 1935. His western allies, especially France, were suspicious of this contract.

In the second half of the 1920s, Beneš was a participant in the meetings of the informal Stammtisch group of Prague intellectuals Pátečníci .

Beneš as President (1935 to 1938)

When Hitler called for the incorporation of the Sudeten areas after the " Anschluss of Austria " in March 1938, Beneš had the Czechoslovak army mobilized and hoped for support from France, with whom an alliance had existed since January 1924, and the ally from the Little Entente in the case of a German Attack. In September 1938, Beneš proposed in an internal letter to his health minister Nečas in Paris that part of the Sudetenland be ceded to Germany (around 5,000 of 28,000 square kilometers, i.e. approx. 18 percent) and at the same time a large part of the German-speaking population remaining in Czechoslovakia (after Beneš 'rough calculations about 2.2 million people) were forcibly evacuated. Britain and France refused to approve this plan after initial promises. Instead, Hitler was granted the Sudetenland in the Munich Agreement (September 1938) in the hope of avoiding war.

After the Munich Agreement, Beneš rejected the offer of military aid from the Soviet Union as unrealistic.

Especially during his time as President, Beneš obtained passports for many Germans and Austrians persecuted by the National Socialists, with which they could emigrate overseas.

Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938 and flew to London a few days later. Shortly afterwards, he congratulated his successor Emil Hácha on his election.

Beneš in exile in London

After some time in exile as a private person , Edvard Beneš founded the Czechoslovak government in exile there in 1940 and claimed the office of president again for himself. In the course of the Second World War , Beneš was finally recognized by the Allies as Czechoslovak President. He now worked intensively towards the restoration of Czechoslovakia within the borders before the Munich Agreement and the complete expulsion of the 3.4 million Germans possible. In a conversation with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 12, 1943, Roosevelt authorized his guest - at least according to Beneš's account - to expel the Germans from Czechoslovakia after the end of the war. In a radio address broadcast from Great Britain on October 27, 1943, Beneš stated:

“In our country the end of this war will be written in blood. The Germans will be repaid without pity and multiplied for all that they have committed in our countries since 1938. The whole nation will take part in this struggle, there will be no Czechoslovaks who evade this task, and no patriot will fail to take just vengeance for the sufferings of the nation. "

As a result of his disappointment with the lack of support from the Western powers in 1938, Beneš increasingly approached the Soviet Union as the most important guarantor for a re-establishment of the Czechoslovak state. After Germany's defeat in the east became foreseeable, he signed a Czechoslovak-Soviet assistance treaty with Stalin on December 12, 1943 in Moscow , which also stipulated close cooperation in the post-war period. At this meeting, Stalin agreed to Beneš's plans to expel the Sudeten and Carpathian Germans and the partial expulsion and expropriation of the 720,000 Hungarians in southern Slovakia. Subsequently, Beneš became one of the strongest supporters of Stalin's intentions to expand the Soviet Union to the west. He welcomed the Polish shift to the west , as it made Germany smaller, and assured Stalin of the Carpathian Ukraine . In Moscow, Beneš agreed with the communists and left- wing socialists under Klement Gottwald to set up a national front from which the other parties of the First Republic would remain excluded. In March 1945 he traveled again to Moscow and negotiated with Gottwald about the participation of the Moscow group in his government, with which he made extensive concessions.

Second presidency (1945 to 1948)

The Košice program developed as a result of his Moscow negotiations was announced on April 5, 1945 in Košice , the provisional seat of the government of the National Front, by Prime Minister Zdeněk Fierlinger . This included the ban on the conservative parties of the First Republic, the reintegration of Slovakia while maintaining its autonomy, the resettlement of citizens of German and Hungarian nationality who had supported the National Socialists, the nationalization of large estates and industrial companies and banks, the punishment of Collaborators and a collaboration with the Soviet Union declared.

In May 1945 Beneš returned to his homeland from the Soviet Union and took over the office of President again. The creation of a unified Czechoslovak national state remained the linchpin of his political program. On June 29, 1945, Edvard Beneš signed the cession of Carpathian Ukraine to the Soviet Union.

Immediately after his return to Prague on May 16, 1945, he announced to an enthusiastic crowd in the Old Town Square :

“It will be necessary…, especially uncompromisingly to completely liquidate the Germans in the Czech countries and the Hungarians in Slovakia, insofar as this liquidation is at all possible in the interests of the unified nation-state of the Czechs and Slovaks. Our slogan must be to finally de-Germanize our country culturally, economically and politically. "

On the other hand, in his speech in Mělník on October 14, 1945, Beneš stated:

“Recently, however, we have been criticized in the international press that the transfer of the Germans was carried out in an undignified, inadmissible manner. We supposedly do the same thing the Germans did to us; we are allegedly attacking our own national tradition and our previously morally unchanged reputation. We are supposedly simply imitating the Nazis in their cruel uncivilized methods.

Whether these accusations are true in detail or not, I declare very categorically: Our Germans must go to the Reich and they will leave in any case. They will leave because of their own horrific moral guilt, because of their actions with us before the war, and because of their entire war policy against our state and our people. Those who are recognized as anti-fascists loyal to our republic can stay with us. But our entire procedure in the matter of their deportation to the Reich must be humane, decent, correct, and morally justified. [...] All subordinate organs that violate it will be called to order very decisively. Under no circumstances will the government allow the republic's reputation to be destroyed by irresponsible elements. "

At the Potsdam conference (final on 2 August 1945), the three victorious allies voted USA , UK and USSR of the transfer (the "Transfer") of the Eastern and Sudeten Germans in "an orderly and humane manner" to. The Sudeten Germans as well as the Hungarians should also be expropriated without compensation as “collaborators and traitors” and undesirable ethnic groups . Germans who had been loyal to Czechoslovakia as citizens during the German occupation should remain unaffected by expropriation and other repression measures according to the Kaschau program . Some of the Beneš decrees issued in October 1945 not only determined the partial nationalization of the Czechoslovak economy, but also a general expropriation and expulsion of Germans beyond the Kaschau program, with a few exceptions.

On February 25, 1948, already seriously ill, Beneš accepted the offer of resignation from the non-communist ministers under pressure and thus enabled the communists to seize power . In May 1948 he refused to sign the new communist constitution , and on June 7, 1948 he resigned.

His successor was Klement Gottwald .

Private

Beneš was married to Hana Benešová (born Anna Vlčková, 1885–1974), with whom he had known since his youth in Paris.

Appreciations

The American Philosophical Society honored him in 1939 for his Penrose Memorial Lecture with the title "Politics as Art and Science" with their Benjamin Franklin Medal .

While no memorial was erected for Edvard Beneš until 1989, his public veneration increased after the Velvet Revolution . Since May 2005 there has been a larger than life statue of Karel Dvořák (1893–1950) for Edvard Beneš on Loretánské náměstí (Loreto Square ), on the Prague Hradcany, directly opposite the Foreign Ministry in the center of Prague ( Prague 1 ). In October 2001, a memorial was opened to him in his summer residence and place of death, Sezimovo Ústí . In addition, numerous streets, bridges and squares were named after him.

In 2011, Jiří Gruša discussed Beneš's double surrender to Hitler and Stalin. He called Beneš “the Czech enigma” (riddle).

See also

literature

- Jiří Gruša : Beneš jako Rakušan. Barrister & Principal, Brno 2011, ISBN 978-80-87474-12-9 . (German: Beneš als Österreicher. Wieser-Verlag, Klagenfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-99029-008-8 . Cover text: The attempt to build monuments for Beneš will be more difficult in the future. )

- Ota Konrád, René Küpper (Hrsg.): Edvard Beneš: Role model and enemy image, political, media and historiographical interpretations. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-525-37302-6 .

- Daniel Neval: Providence and Mission. Politics and history with Edvard Beneš. Edition Kirchhof & Franke, Leipzig / Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-933816-24-6 .

- Florian Ruttner: Edvard Beneš and the criticism of National Socialism. Ca ira Feiburg, Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-86259-147-3 .

-

Zbyněk Zeman , Antonín Klimek : The Life of Edvard Beneš 1884–1948: Czechoslovakia in Peace and War. Oxford University Press / Clarendon Press , Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-19-820583-X ,

in Czech: Zbyněk Zeman: Edvard Beneš - politický životopis. Mladá fronta , 2000, druhé vydání 2009, ISBN 978-80-204-2062-6

( book review in English by Richard Crampton on ce-review.org ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Edvard Beneš in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Edvard Beneš in the German Digital Library

- Literature and other media by and about Edvard Beneš in the catalog of the National Library of the Czech Republic

- Newspaper article about Edvard Beneš in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ See his study Stranictví. Sociologická study , Prague 1912.

- ↑ "Détruisez l'Autriche-Hongrie" (1916)

- ^ Daniel E. Miller: Forging Political Compromise. Antonín Švehla and the Czechoslovak Republican Party 1918–1933. Pittsburgh 1999, p. 122.

- ^ A b Rudolf Chmel: On the national self-image of the Slovaks in the 20th century. In: Alfrun Kliems (ed.): Slovak culture and literature in self-understanding and understanding of others. Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, p. 13 ff., Here p. 22.

- ^ Giorgio Petracchi: Dietro le quinte del convengo Volta sull'Europa. Un piano per sovvertire l'Europa centro-orientale . In: Maddalena Guiotto, Wolfgang Wohnout (ed.): Italy and Austria in Central Europe in the interwar period / Italia e Austria nella Mitteleuropa tra le due guerre mondiali . Böhlau, Vienna 2018, ISBN 978-3-205-20269-1 , p. 107 .

- ↑ Václav Stehlík: Stari Friday Men Novodobí a Zpátečníci! , online at: vasevec.parlamentnilisty.cz / ...

- ^ Igor Lukeš: Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler: The Diplomacy of Edvard Benes in the 1930s. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- ^ Igor Lukes: On the edge of the Cold War. American diplomats and spies in postwar Prague . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-516679-8 , pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Karel Kaplan: The fateful alliance. Infiltration, conformity and annihilation of the Czechoslovak Social Democracy 1944–1954. Pol-Verlag, Wuppertal 1984, ISBN 3-9800905-0-7 (Introduction by the author, p. 15 ff.)

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch : History of Bohemia. P. 435.

- ↑ Alexander Place: Dr. Edvard Beneš: evropský politics. 1993, p. 191.

- ↑ Quoted from Věra Olivová: Odsun Němců: výbor z pamětí a projevů dopln ̌ený edičními přílohami. 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Awards and medals for Edvard Beneš

- ↑ See literature.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Beneš, Edvard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Czechoslovak Foreign Minister and President |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 28, 1884 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kožlany , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 3, 1948 |

| Place of death | Sezimovo Ústí , Czechoslovakia |