Fritz Klimsch

Fritz Klimsch (born February 10, 1870 in Frankfurt am Main , † March 30, 1960 in Freiburg ) was a German sculptor and medalist . He came from the Frankfurt artist and entrepreneurial family Klimsch and was the younger brother of the painter Paul Klimsch .

Live and act

Klimsch was the son of the illustrator Eugen Klimsch and grandson of the painter and lithographer Ferdinand Klimsch ; his older brothers Karl and Paul worked as painters. He studied at the Royal Academic University for the Fine Arts in Berlin, where he was a student of Fritz Schaper . Between 1892 and 1900 he stayed repeatedly in the Villa Strohl-Fern in Rome. In 1894 he married Irma Lauter (1872–1948), and the marriage had four children. Klimsch founded the Berlin Secession in 1898 together with Walter Leistikow and Max Liebermann . From 1912 Klimsch was a member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts and from 1916 its senator. From 1921 until his retirement in 1935 he worked as a professor at the United State Schools in Berlin. In 1920 he was a co-founder of the Free Secession . One of his patrons was the industrialist Carl Duisberg .

Klimsch was one of the most famous sculptors during the Weimar Republic . After 1933, he adapted his style to the tastes of the Nazi party celebrities and created - like Arno Breker and Georg Kolbe - numerous naturalistic (mostly female) nudes. Works of art by Klimsch were prestigious luxury goods that also interested the National Socialists. However, it should not be until after the seizure of power that leaders of the regime, etc. a. Hitler, could buy such works, or commissioned them from Klimsch, including busts of Ludendorff , Wilhelm Frick , Hitler , and the actress Marianne Hoppe . Joseph Goebbels described Klimsch in his diary as “the most mature of our sculptors. A genius. How he treats marble. ”Klimsch was regularly represented at the Great German Art Exhibition from 1937 to 1944 in Munich. The private purchase of his works by major players in the regime was followed by government contracts for fountain sculptures for the Goebbels and Göring ministries . At the exhibitions of German artists and the SS , his works youth , girl figure in robe and a young man figure were shown. From March 26th to April 24th, 1938, the Main Office of Fine Arts held a retrospective of his works from the past 15 years in the exhibition building in Tiergartenstraße in Berlin in the office of the Führer’s representative for the entire intellectual and ideological education of the NSDAP ( Amt Rosenberg ). In 1938, on behalf of the Goebbels Ministry, he worked on a Mozart monument for Salzburg (model designs destroyed in 1945); he calculated 300,000 Reichsmarks for five larger-than-life figures in marble (four female and one male). A copy of his bronze nude statue "Olympia" was placed in the garden of Hitler's Reich Chancellery. On his 70th birthday in 1940 Hitler awarded him the Goethe Medal for Art and Science - the award of the eagle shield , which Goebbels had actually applied for, did not materialize for technical reasons. In 1944, in the final phase of the Second World War , Hitler named him on the special list of the God- gifted lists among the 12 most important visual artists of the Nazi regime. Fritz Klimsch's membership in the NSDAP is controversial. Despite the admiration by the National Socialists, Klimsch's membership in the NSDAP has not been proven. As a victim of the Nazi regime, he was excluded from the newly founded Academy of the Arts in 1955.

After the Second World War, Klimsch relocated to Salzburg with his wife Irma and family, but was expelled as Reich German by Mayor Richard Hildmann with his family on February 8, 1946 . The family came to Freiburg via Munich. His son Uli and his wife Liesl took him in at the Hierahof in Saig .

For his 90th birthday in 1960, the then Baden-Württemberg Interior Minister Filbinger awarded him the Great Cross of Merit . Fritz Klimsch died in a clinic in Freiburg im Breisgau on March 30, 1960. He had been an honorary citizen of Saig since 1955 , where he was buried on April 2, 1960.

Artistic development

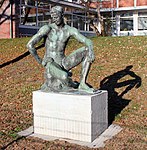

Study trips to Italy (1895, 1901) and Greece (1901) influenced Klimsch's artistic style, which was subject to various changes and was initially based on Begas . Before the First World War, influences from Hildebrand and Maillol could be seen, in the twenties also from Wilhelm Lehmbruck . From the late 1920s, Klimsch created (preferably female) nudes. Klimsch named only "Hellas" as inspiration. The best known was the 'Die Hockende' from 1928. a. 'The Seeing One', 'The Wave', 'In Wind and Sun', 'The Youth', 'Summer Day', 'Olympia', 'Galatea', 'The Dreaming Woman', 'The Reclining Woman', 'A View into the Distance' . Of these expensive bronze sculptures, Rosenthal made smaller, more affordable figures out of biscuit porcelain , which corresponded entirely to the originals in terms of surface and shape.

After he settled in the Black Forest after the end of the war, he lived in seclusion and created only a few small-format works.

Works (selection)

Sculptures

- Der Gefesselte , shown at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1892 .

- Bust of Mrs. St. (marble) and girl while undressing (bronze), both shown in 1904 at the first exhibition of the German Association of Artists in the Royal Exhibition Building on Königsplatz in Munich.

- Hermes or Merkur , marble sculpture, foundation for the Handelshochschule Berlin in 1907 (today foyer ballroom of the economics faculty of the Humboldt University of Berlin )

- Bust of Max Liebermann , bronze, 1912, 1917 exhibited at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in Düsseldorf .

- The Sower , also called Nackter Bauer , 1912, bronze, since 1986 on Klemensplatz in Düsseldorf-Kaiserswerth (previously from 1955 in Elisenpark in Aachen), a foundation of the architect Walter Brune

- The bowed man in Slupsk 1918/1919

- Nike , 1920 (for Bayer)

- Emil Fischer , 1921, Luisenplatz Berlin

- Ullstein owl on the entrance pavilion of the " Ullstein-Druckhaus " in Berlin-Tempelhof, 1927

- Nymph on the water 1930 (Frankfurt am Main)

- The crouching woman , 1928

- Maja , 1931, in front of the Heimatmuseum Berlin-Köpenick , originally installed in the Müggelsee lido in Berlin-Rahnsdorf .

- Eva , 1934

- The Looker , 1932, Carl-Duisberg-Bad, Friedrich-Ebert-Straße, Leverkusen

- In Wind und Sonne , 1936, in the Grugapark in Essen

- The little looking one , 1936, Great German Art Exhibition Munich 1937

- Striding , bronze 1936

- Athlete , erected in 1937 at the main entrance of the Mürwik Naval School

- Die Schauende , 1938 Autobahn rest house on Chiemsee

- The wave in the Kyritz rose garden

- The one who thinks

- Summer day

- Galatea

- Olympia , 1936, was seized together with Galatea in a major raid in Bad Dürkheim in 2015 .

- Olympia , 1937, set up in a green area at the town hall in Gelsenkirchen-Buer

Nymph on the water ( Frankfurt am Main )

Seated (1925) Berlin-Reinickendorf

The wave (1940/1941) in the rose garden of Kyritz

Monuments

- Berlin: Rudolf Virchow monument, on Karlplatz in front of the Charité (created 1906–1910)

- Saarbrücken: Uhlan monument of the Uhlan regiment "Grand Duke Friedrich von Baden" (Rheinisches) No. 7 , (unveiled 1913)

- Berlin: Emil Fischer -Sitzbild (sandstone, 1921, original destroyed; bronze replicas in Dahlem and Mitte)

- Wetzlar: Battalion monument 1914/1918 of the Rhenish Jäger Battalion No. 8 (1924)

- Leverkusen-Opladen: "Stahlhelm" war memorial, Rennbaumstrasse cemetery of honor (formerly the central part of the facility in the honor grove of Bayer factory colony III in Leverkusen-Wiesdorf)

Monument to Rudolf Virchow (1906–1910)

War memorial "Stahlhelm" (around 1920) Opladen

Funerary monuments

- Berlin-Nikolassee - Gravestone of his son Reinold Klimsch (1918), wall grave of the lawyer Friedrich Ernst (1915) and grave monument for the painter Theo von Brockhusen (1919), all in the Evangelical Cemetery Nikolassee

- Stahnsdorf - grave memorial with a relief plaque of General Alexander von Kluck , on the south-west cemetery Stahnsdorf

- Nordfriedhof (Düsseldorf) , field 72 - Behrens tomb

- Südfriedhof Leipzig - Section III / 7, grave site Julius Friedrich Meissner, sandstone (1903)

- Main cemetery Frankfurt am Main - Alois Alzheimer's tomb (1915)

- Flora temple for Carl Duisberg in Carl-Duisberg-Park (Chempark / Bayerwerk), Kaiser-Wilhelm-Allee, Leverkusen

Monumental group of figures Tomb Meissner, Südfriedhof Leipzig (1903)

Flora temple resting place Carl Duisberg

Competition participation (s)

- In 1900 the Prussian Ministry of Culture organized an open art competition to design a monumental fountain for Minervaplatz in Opole , in which Klimsch, who at that time lived in Charlottenburg , took part. The general requirement was "... to create a serious, characteristic work of German art". Klimsch had modeled a sea centaur thrusting into a conch shell . A total of ten designs were awarded prizes by a jury; Klimsch's design was shortlisted, but was not implemented. Instead, the Ceres Fountain could be built in a short time.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 2010/2011: August Gaul - Fritz Klimsch , Museum Giersch , Frankfurt am Main

literature

- Hermann Braun: Fritz Klimsch. A documentation. VAN HAM Art Publications, Cologne, ISBN 3-9802780-0-X .

- Hermann Braun: Fritz Klimsch. Works. ISBN 3-922612-00-8

- Robert Thoms: Great German Art Exhibition Munich 1937–1944. Directory of artists in two volumes, Volume II: Sculptors. Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-937294-02-5 .

- Florian Hufnagl: Klimsch, Fritz. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , p. 69 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Uli Klimsch: Fritz Klimsch, The World of the Sculptor. Berlin 1938.

- Fritz Klimsch . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General lexicon of fine artists from antiquity to the present . Founded by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker . tape 20 : Kaufmann – Knilling . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1927, p. 502 .

- Klimsch, Fritz In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General Lexicon of Fine Artists of the XX. Century. Sixth volume (supplements HZ) , EA Seemann, Leipzig 1999 (study edition). ISBN 3-363-00730-2 (p. 146f)

Web links

- Literature by and about Fritz Klimsch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Fritz Klimsch's CV at Ketterer Kunst

- Berlin State Monument List: Monument to Rudolf Virchow

- Works by Fritz Klimsch

- Frankfurt main cemetery: gravesites of the Klimsch family

- Works by Klimsch in the Great German Art Exhibition in the Haus der Kunst , Munich

- Fritz Klimsch at the age of 85 in “Welt im Bild” newsreel

- LEO-BW Fritz Klimsch

Individual evidence

- ^ Artist: Prof. Fritz Klimsch. German Society for Medal Art V., accessed on November 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Carl Reissner: Gestalten around Hindenburg: leading figures of the republic and the Berlin society of today. Berlin 1930, p. 201.

- ↑ Fritz Klimsch 1939 . In: Art for All . Volume 55, 1939, p. 108–114 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on November 11, 2016]).

- ↑ Norbert Westenrieder: "German women and girls!" From everyday life 1933–1945. Photographed contemporary history . Droste, Düsseldorf 1984.

- ^ Fritz Klimsch: Bust of Adolf Hitler. Retrieved June 8, 2017 .

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 312.

- ↑ Harald Olbrich (Ed.): Lexicon of Art. Architecture, fine arts, applied arts, industrial design, art theory. Volume III: Greg – conv. EA Seemann Verlag, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-86502-084-4 , p. 786.

- ^ Kurt Luther, German Art Society, Karlsruhe (ed.): In: Das Bild. Monthly magazine for German art, past and present. No. 11, CF Müller, Karlsruhe November 1938. - Book review on: Uli Klimsch: Fritz Klimsch: the world of the sculptor (= art books of the people . Volume 23 ). Rembrandt-Verlag, Berlin 1938.

- ↑ Claudia Marcy (ed.): Space for art. Artist studios in Charlottenburg . Edition AB-Fischer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937434-11-9 , ill. P. 45 .

- ↑ Federal Archives R 55/21013 pp. 97 ff.

- ^ Ernst-Adolf Chantelau: The bronze statues of Tuaillon, Thorak, Klimsch and Ambrosi for Hitler's garden . A contribution to the topography of the New Reich Chancellery by Albert Speer. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2019, ISBN 978-3-7494-9036-3 .

- ↑ Otto Thomae: The Propaganda Machine. Fine arts and public relations in the Third Reich . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-7861-1159-6 , p. 196, 282-283 .

- ^ Ernst Klee: The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 311.

- ^ Foundation archive of the Academy of Arts. (Ed.): "And the past is always at the table". Documents on the history of the Academy of Arts (West) 1945 / 46-1993 . Selected and commented by Christine Fischer-Defoy . Henschel, Berlin 1997, p. 580 : “With the visual artists Bleeker, Geßner, Hoffmann, Kampf, Klimsch, Nolde, Schmitthenner, the musicians Butting and Trapp as well as the poets Schmidtbonn and von Scholz eleven former NSDAP members are named, whose further activities in the academy 1945/46 was still categorically excluded. "

- ^ Paul Malliavin: Écrits de Paris-revue des questions actuelles. Issues 639–649. Center d'études des questions actuelles, politiques, économiques et sociales, 2002 (no side view, books.google.de ). « Josef Thorak and Fritz Klimsch qui, bien que jouissant d'une importante aide logistique de l'appareil nazi, n'étaient pas membres du NSDAP. »(German:" Josef Thorak and Fritz Klimsch, although they received significant logistical help from the Nazi system, were not members of the NSDAP. ")

- ↑ There is no evidence of NSDAP membership in the Federal Archives

- ↑ "and the past is always at the table". Documents on the history of the Academy of Arts (West) 1945 / 46-1993 . Henschel, Berlin 1997, p. 167 (Published by the Foundation Archive of the Academy of Arts. Selected and commented on by Christine Fischer-Defoy).

- ↑ a b ostendorff.de: Biography , accessed on December 26, 2015.

- ↑ frankfurter-hauptfriedhof.de: klimsch-fritz.pdf (application / pdf-Objekt; 18 kB) , accessed on August 19, 2011.

- ↑ Fritz Klimsch 1912 . In: Art for All . Volume 27, 1912 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on November 11, 2016]).

- ^ Wilhelm Bode : Thoughts on the Fritz Klimsch exhibition in the Free Secession in Berlin . In: Art for All . 36th volume, 1920, p. 28–39 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on November 7, 2016]): “The endeavor is characteristic not only of Klimsch, but of the whole time and direction of sculpture to which the artist belongs to give his large naked figures 'interesting' or 'piquant' positions and movements. "

- ↑ The Noack Foundry. On the thirtieth anniversary of the Noack bronze foundry in Berlin-Friedenau in 1927. In: Gustav Eugen Diehl (Hrsg.): Publications of the Kunnstarchiv . No. 47 . GEDiehl, Berlin 1927, p. 30–32 ( noack-bronze.com [PDF; accessed November 9, 2016]).

- ↑ Bruno E. Werner: Spring exhibition of the Prussian Academy of the Arts . In: Art for All . Volume 42, 1926, p. 330–337 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on November 9, 2016]).

- ↑ Dieter Struss: Rosenthal. Service, figurines, ornamental and art objects. Battenberg, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-89441-211-9 , p. 84.

- ↑ Fritz Klimsch. In: kettererkunst.de

- ^ Exhibition catalog X. Exhibition of the Munich Secession: The German Association of Artists (in connection with an exhibition of exquisite products of the arts in the craft). Publishing house F. Bruckmann, Munich 1904, p. 39.

- ^ Fritz Klimsch: Bust of Prof. Dr. Max Liebermann (illustration) , in the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf in 1917

- ↑ Bayer. State Office for Monument Preservation: "Monument Protection Information" No. 142, March 2009, p. 44/45

- ^ Heinrich Hoffmann: Fritz Klimsch. The Woge.Great German Art Exhibition June 20, 1942. Image no .: 50086586. Bildagentur bpk, June 20, 1942, accessed on August 26, 2020 .

- ↑ Andre Reichel: Artwork from the Kyritz rose garden in danger. In: Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung. April 8, 2019, accessed August 26, 2020 .

- ↑ Konstantin von Hammerstein: "Brown Masters". In: Der Spiegel . 22/2015 (23 May 2015), p. 48 f.

- ↑ Berliner Architekturwelt , edition 3.1901, issue 9; P. 333

- ^ Fontanna Ceres in Opole, Minervaplatz; 1902

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Klimsch, Fritz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sculptor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 10, 1870 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 30, 1960 |

| Place of death | Freiburg in Breisgau |