Georgi Vladimirovich Ivanov

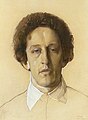

Georgi Vladimirovich Ivanov ( Russian Георгий Владимирович Иванов , scientific. Transliteration Georgy Vladimirovič Ivanov ; born October 29 . Jul / 10. November 1894 greg. In Puke, volost Seda , Kovno Governorate , Russian Empire , now mažeikiai district municipality , district Telšiai , Lithuania ; † August 26, 1958 in Hyères , Var department , France) was a Russian poet, writer, publicist, critic and translator. He is considered one of the most important poets of Russian emigration and one of the first literary existentialists in Russian literature .

Life and work

The Russian Years (1894-1922)

Childhood and youth

Georgi Ivanov was born on October 29, 1894 in Puke, the estate of the Brennstein family, in the Telsche district of the Kovno governorate of the Lithuanian province of the Russian Empire as the fourth child of his parents. His father, Vladimir Ivanovich Ivanov (December 5, 1852– March 11, 1907), was an artillery officer. He came from an old Russian noble family from the Vitebsk Governorate (now Belarus ). Ivanov's mother, Wera Michajlowna Iwanowa, (January 11, 1859–192?), Née Brennstein, came from a German noble family from brewers to Brennstein . One of her ancestors moved to Russia and made a brilliant military career at the court of the Russian tsars. His two descendants were loyal companions of Tsar Nikolai I. The family name was Russified, so that from the second generation of Brennstein onwards, it was adapted to the Russian spelling Brenschtein . In addition to Georgi, there were three other siblings in the family: Wladimir, geb. May 28, 1880, Natalija, b. October 1, 1881 and Nikolai, b. December 24, 1884.

Georgi's father had a successful military service behind him: he fought in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) , then from 1881 to 1885 he served in Sofia at the court of the first prince of Bulgaria, Alexander Battenberg (1879–1886). At the time Georgi was born, he served again in Russia in the Wilno military district in the Kovno garrison , later directly in Wilno . In 1902 he quit his military service. In 1899 Ivanov's father bought the Studenka estate near Novogrudok in the Minsk governorate . In 1902 Ivanov's father bought the next larger estate near Wilno , the Sorokpol estate. The Ivanov family spent their holidays in this estate until the outbreak of World War I. Ivanov's father quickly sold the Studenka estate, or the property, largely piece by piece to the neighboring farmers; the rest of the estate was forcibly auctioned off after his death (March 1907).

In 1904 the Ivanov family moved from Vilno to Petersburg . From 1905 onwards, Ivanov's mother, Wera Michajlowna, lived with the children at 12 Officer'skaya in St. Petersburg. From August 15, 1905, Georgi was brought to the Cadet Corps in Yaroslavl for military training.

Georgi was the youngest child in the family. From birth he seemed to be a very weak, frail child with health problems, and was pampered and protected by it, especially by his sister Natalija, 13 years older than him. She taught Georgi a love of reading and literature and replaced him with all of the nonexistent comrades of his childhood. Natalija was his only friend and comrade to the end. She supported Georgi during his poetic career and seized the opportunity to free him prematurely from military school.

Georgi was in the cadet corps for six years, but only completed four classes. He had to repeat the second and third school year for health reasons. In January 1907, at the urgent request of his father, Georgi was transferred from Yaroslavl to St. Petersburg in the Second Petersburg Cadet Corps. On March 11, 1907, his father committed suicide in Dvinsk (now Daugavpils , Latvia ). As a result, the young Ivanov fell seriously ill and was unable to attend classes in the new corps for a whole school year. Although it became clear when he was accepted into the cadet corps that Georgi was unsuitable for military training due to his frailty and poor health, his father had intended him for military service. Ivanov later wrote about this time that it had been "a misunderstanding" and that he "looked behind every high school student with envy". But not only Ivanov's health troubled him, but also his instability.

He could not bear the discipline of the military school and only his love for literature and reading helped him to avert and cope with everyday military school life. He read many books, often banned ones, was seized with modern poetry and soon began to write himself. At the age of 15 he successfully published his first poems and quickly became known in the entire Petersburg literary scene.

Petersburg literary scene and the young Georgi Ivanov

"The fifteen year old beginner"

As early as 1910 he was introduced as a “15-year-old promising poet” in the “Academy of Poetry”, where Vyacheslav Ivanov refined the final poetic touch for “the best of the best”. Already at this time Georgi surrounded himself with literary greats from Petersburg such as Mikhail Kuzmin , Sergei Gorodezki , Georgi Tschulkow , Yuri Annenkow as well as with Alexander Blok , Igor Severjanin , Nikolai Kulbin , Velimir Khlebnikow , Alexei Kruchonych , Vladimir Mayakovsky and many others. He wrote sonorous poems on subjects that were unusual for the poetry of the time, which initially fascinated everyone. The 15-year-old cadet had no life experience, so he processed everything he saw, felt or what came in his imagination in his rhymes. Often he only described one or the other portrait, an everyday scene or situation that inspired his imagination. Alexander Blok warned him: "The poet should write about love and death ..." But the young cadet had not yet found love, and the duties of the military school tormented him. At that time he led a very precarious life: in military school he was a good cadet, outside a successful, promising young poet. He took three months' sick leave from school and at the same time worked as the editor of the poetry department of the magazine "Gaudeamus". In addition, he constantly violated the regulations of the cadet corps by visiting "forbidden" pubs where the Petersburg bohemians gathered.

Georgi had already decided on a career as a poet in 1909, but he was not yet able to leave the cadet corps himself as he was not yet of legal age. His sister freed him from this dilemma. In October 1911 he was released from the fifth grade of the cadet corps, without leaving school in the "care of his mother". In December 1911 his first volume of poetry Otplytie na o. Ziteru with the subtitle Poesy (The Embarkation to Island Kythera. Rhymes) was published by the publishing house of the Ego-Futurists. Georgi was young and interested in all the literary currents and tendencies that were abundant in Petersburg at that time. He was well acquainted with all schools of the time: symbolists , futurists , ego-futurists, then with acmeists . But none of these movements could convince him, not even the acmeists.

In January 1912 he was given by Nikolai Gumiljow in Zech Poetow (poets' guild ), the "Zech" in which the so-called acmeists were later (there were only six acmeists from 36 members of the entire guild), without any vote, which was otherwise mandatory was accepted, but Ivanov never counted himself to this acmeistic group, but certainly to "Zech", the association of poets, which he valued and which for Georgi became one of the most important schools of poetry .

Poets' Guild (Zech Poetow)

Many members of the "Zech" later became famous poets : Nikolai Gumiljow , the organizer of the "Zech", Anna Akhmatova , Gumilev's first wife, who consequently became a successful poet, Ossip Mandelstam , Vladimir Narbut , Vasily Gippius, Mikhail Losinsky and many others . In the "Zech" there were very strict rules, as well as the task of writing poetry, reading it in front of the members, commenting on it and then publishing it, which was beneficial to Ivanov. Innokenti Annenski was considered the spiritual father of the members of the "Zech" . Georgi Ivanov missed school, so "Zech" was all the more a kind of school substitute for him and just as it should be in a good school, Ivanov published his second volume of poetry Gornitsa (The good room) in 1914 :

The

autumn evening shines in faded gold and cold blue over the Neva.

The lanterns cast a muted glow on the waves,

And the boats sway slightly on the quay.

Grumpy boatswain, put your oars down!

I want to let the current drift us.

Surrender to the restless soul, full of joy, To the

fleeting harmony of the pale sunset.

And the waves splash on the dark board.

Reality merged with an airy dream.

The noise of the city subsided. The fetters of sadness loosened.

And the soul feels the touch of the muse.

And so in 1914 Ivanov's future bow to the melancholy motif Toska (Sehnsucht / Wehmut, Russian тоска ), which was one of the most popular motifs for Innokenti Annenski and was most often used as a word in his poetry , was already evident in this poem . One can say as if Georgi Ivanov took over a relay from Annenski's hand.

Annenski's legacy as the success of Ivanov's later poetry

Georgi Ivanov later openly acknowledged the importance of Innokenti Annenski for his poetry. Annensky, and not Gumilev, was his "spiritual father". The members of the "Zech" saw the recently deceased poet Annenski as their leader in the renewal of poetry, and Nikolai Gumiljow even knew Innokenti Annenski personally and promoted him as a role model to the young poets, but he probably did not actually understand him . Georgi Ivanov saw Annenski's poetry, more precisely in Annenski's last poem Moja toska (My Longing), as a revelation. He has discovered a real key to new doors in poetry: in Annenski's favorite word and the motif of Annenski's Toska (longing / melancholy) Ivanov saw the strength and potential of a word that opened up a handful of new opportunities for his poetry. The word toska , which occurs very often as a motif in Russian songs and ancient romances, and is so popular with the Russian people in general, explains a dull state of unattainable, distressed inner unrest, or fear of the soul, the elusive feeling of a person, who loses the ground under his feet, or a mood that corresponds to melancholy, sadness, sadness, melancholy, boredom, longing, homesickness, and even despair. This motif becomes the main motif of Ivanov's later work, as he dresses in words the inner pain of his homeless contemporaries, the restlessness of the human heart and the futility of existence.

Georgi Ivanov understood Annenski's statement literally as the last will of the poet, to which he remained so faithful until the end of his life that he himself went down in Russian literary history as the unique “master of yearning” ( мастер тоски ).

Georgi Ivanov learned to devote himself to the word as such in the “Zech”, where Annenski's preferences for philology were being propagated.

Maximilian Voloshin wrote in memory of Annensky :

“He was a philologist because he was fond of the origin of the human word […] Innokenti Fedorowitsch was aware that for him the outside world offers nothing more than the word; he himself was full of passion for beauty and brilliance, for the restlessness and despondency of the terrible, powerful, enigmatic everyday words. "

That is why Ivanov found in Annensky's poetry a real treasure for the future purpose of his poetry and thereby discovered a new, sovereign way of his poetry. Later in the emigration, Ivanov wrote a poem on the subject Toska and on "Key", which gave him this motif:

I never knew love, never knew compassion.

Explain to me - what is the vaunted happiness that

poets have spoken of for ages?

[...]

Happiness is a quiet night river,

on which we swim until we go down,

in the direction of the deceptive light, a firefly ...

Or something like that:

There is a synonym for everything on earth,

The patent key for every type of lock is -

the icy magic word : T oska [longing / sadness / despair]

The “icy magic word: Toska”, (Russian) т о с к а, became for Georgi Ivanov a “patent key” for every type of “lock”. With him he later opened the hearts of his uprooted fellow human beings and with him Ivanov also found access to all existential topics that were previously closed. With this "patent key" Ivanov created his unique poetry, which was deeply "Russian" poetry at its core, but at the same time the "existentialist" one, since it was about the existence of Russian emigrants who lived their miserable fate voluntarily.

Ivanov later described the appreciation for Annensky in his memoirs Peterburgskie zimy (The Petersburg winters). The title of the book is also based directly on Annenski's poem Peterburg . Ivanov repeated his appreciation of Annensky several times in his letters, also often in his later poetry, and very often Annensky is considered in the background of his poetry and occurs frequently. Annenski's motif Toska (longing / wistfulness) gave Georgi Iwanow an even wider range for his poetry, especially when he was emigrating, one can even say for the later philosophizing about the meaning of life and death. Ivanov wrote openly about the fact that he owed his crown of the “Prince of Russian Emigration” only to Innokenti Annensky:

Spring said nothing to me -

it couldn't. Maybe - he found no words.

Only in the dim aisle of the station did

an insignificant chandelier come on.

Only someone bowed to someone

on the platform in the night blue,

Only the crown sparkled weakly

on my unhappy head.

On November 30, 1909, Annensky suddenly died of a heart attack on the stairs of the Tsarskoselsky train station in Petersburg. Georgi Ivanov was a young beginner at the time and did not know Annensky personally, but never tired of reiterating his inner bond with Annensky. As a 15-year-old Ivanov wrote his first review of the posthumously published volume of poems Kiparisowy larez (The Cypress Box ), which was published a few weeks after Annenski's death. During his emigration, Ivanov emphasized the importance of Annenski for his later development in his poetry:

I like the hopeless calm,

In October - blooming chrysanthemums,

The glimmer of light behind the misty river,

The wretchedness of the faded evening glow.

The silence of the anonymous graves,

all the banalities of the “song without words”,

that which Annensky

liked so greedily,

that which Gumilew could not stand.

Through Annenski's nostalgia motif, Ivanov discovered a new path for Russian poetry, which gave him the opportunity to use simple words to express the misery of everyday life in poetic language and to raise the misery of existence to the height of poetry.

Annenski, who was a great philologist, could only have been proud of what his successor was able to create from his favorite word and motif.

Petersburg, Petrograd and Ivanov's literary successes

In 1914 the First World War began, which surprised Ivanov in the Sorokpol estate near Wilno. He returned to Petersburg without knowing that he would never again be able to step on the grounds of the estate near Wilno. In 1915 the Germans occupied this part of the Russian Empire, in 1917 the Russian Revolution came , in 1918 Lithuania liberated itself from the Russian Empire, in 1920 the Wilno district was occupied by Poland until the Second World War. The Ivanovs' family lost their Sorokpol estate near Wilno.

At that time there was a patriotic mood in Petersburg and all poets supported it with their poems. Georgi Ivanov became a very sought-after and desirable author in all magazines during this period. His poems, compared to his famous colleagues, were “with or without patriotic content” much lighter and more sonorous than heavy “projectiles” by Mikhail Kuzmin, Fyodor Sologub or Sergei Gorodetsky. That placed Ivanov very high in the literary hierarchy of the Petersburg circles. After Gumilyov's voluntary departure to the front, the “Zech” poets' association temporarily ended its existence. Ivanov took Gumilev's place in the magazine “Apollon”, which he valued very much, where he headed the “Novelty in Poetry” section. In 1915 he published his next volume of poetry, Pamjatnik slawy (Monument to Fame). Later he himself rated this volume of poetry as the "emulation of patriotism", and the poems scornfully as "the cheap glass beads". Ivanov did not really do justice to his writing during this period. A closer look at some of these poems reveals its later handling: to put important remarks in between lines that force you to pause and think while reading. In the poem Opjat na Ploschtschadi Dvorzowoi (Back on Palace Square) he describes an ordinary everyday life in Petersburg, and if it weren't for an unusual line in between, about the “carefree laughter” and the “living faces” in the smooth description of the winter day, If you hadn't noticed that we're talking about a winter's day during the war, when the calm day of the capital is in stark contrast to dying in war. This "stumbling block" method is very characteristic of the later Ivanov.

Back on the Schlossplatz,

the pillar shines silver.

The

frosty frost lay like a carpet on reverberant wooden pavement.

Sleigh after sleigh chase,

From the horses the steam rises,

Under the hasty steps

the frozen sidewalk clinks.

Carefree laughter ... Living faces ...

The campfire happy light -

the Neva capital is beautiful

on such sunny days.

You walk and breathe with full chest,

you descend on the ice of the Neva

And the wind above you

Broad, sunny flight.

And the heart rejoices,

And life is cheerful again,

And in the pale sky shines clearly

The needle of the Admiralty.

In 1916 he published his next volume of poetry, Weresk (The Heidenkraut). For Georgi Ivanov personally this volume became meaningful, although the criticism was devastating: the war was still going on and the author continued to describe beautiful landscapes and pictures; he is very attached to this volume and published it again when he emigrated. It was not until many years later that research succeeded in establishing that this volume was intended by him as something of a “memorial” to Ivanov's family. Even behind the title of the volume “Das Heidenkraut” hides the name of the Puke estate (lit. Puokė), which means “cotton grass” in Old Lithuanian, which usually grows next to the heather. In Weresk many poems are hidden with respect to his family: some descriptions of portraits of great-grandfather, grandfather and many with memories of his teenage years in the Lithuanian provinces, which he described as "my Scotland".

Scotland, your misty shore,

And the pastures with the green grass,

Where smooth cattle rest,

How sad to leave you forever!

Perhaps for the last time I will see

What eludes the eye there in the distance,

And father's hill between willow rice,

And the peaceful shelter of my beloved ...

Goodbye, goodbye! Oh heather, oh mist ...

The distance fades, the ocean whispers,

And carries our ship away like a boat ...

God preserve my Scotland!

Georgi Ivanov irrevocably repeated his departure from the Lithuanian provinces in 1920, since the Wilno district, where Ivanov's family estate "Sorokpol" was located, was illegally occupied by Poles:

Now I know - it's all imagination ...

My Scotland, my longing.

[...]

Your exile, he loves nobody,

He will never return.

And leaving this sad world,

which he so eagerly hid in his memory,

Never turns around when he heard in the distance

A horn blowing “Forgive poet”.

The First World War brought Russia two revolutions in 1917. (The "October Revolution" really should not as a revolution but as a coup are referred to, although it is called by historians as the. Bolsheviks were already in power than they to overthrow the Kerensky - government . Organized) the country, which had already been demoralized by the war, was destroyed to the ground. Whoever escaped, fled. Ivanov also tried to leave the country legally in 1918: his first wife, the French Isabell Ternisien, left Russia with her father with his daughter Elena in 1917, right after the coup. Ivanov tried to follow them. However, he did not succeed. He had to stay in the country for another five “terrible years”. From 1918 he worked as a translator for Maxim Gorkis Verlag Wsemirnaja literatura (world literature) and translated many works of Western poetry into Russian. The following are known from English: by Samuel T. Coleridges Christabel , by GG Byron Mazeppa and Corsar , the poetry by William Wordsworth and from the French the authors such as Théophile Gautier , Charles Baudelaire , Albert Victor Samain , parts of José-Maria de Heredias Les trophées , then together with Georgi Adamowitsch La Pucelle d'Orléans by Voltaire . At this time he organized together with Nikolai Gumiljow the next poets guild ( Zech Poetow ) and is active on the committee of the official Petersburg poets association. As the secretary of the association, he alone was allowed to decide who was allowed to become a new member and thus who was allowed to carry the desirable title of poet as a candidate. Ivanov also accepted Anna Akhmatova into the poets' association, thereby ensuring her survival in the time of " war communism " and making her later career with the Soviets possible.

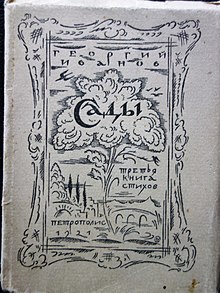

It was not until September 1921 that Georgi Ivanov succeeded in publishing his next volume of poetry, Sady (Gardens). After the October Revolution there were no more publishers or magazines, just for Bolshevik propaganda, so that the publication of other authors was made difficult or impossible. This volume is special for the Petersburg period of Ivanov's work: it was there that Georgi Ivanov spoke for the first time about other topics, about love, the transience of emotions and death. With this volume, the poet Ivanov is in his full height, he has matured, his feelings about his future second wife Iraide Heinicke (pseudonym Irina Odoewcewa) flow in unique rhymes. The Soviet criticism was derogatory: the country was completely destroyed, poverty and hunger everywhere, and Ivanov described wonderful, fairytale gardens of love. Thanks to the beauty of these gardens, much of the anti-Soviet content of the poems, which was obviously hidden behind the enchanting facades, went unnoticed. Even the strict Bolshevik censorship was so hostile to Ivanov's aesthetic preferences that they did not notice the background of the beautiful covers. Georgi Ivanov was known as an esthete from the very beginning. After October this feature of his poetry became his protection.

August 1921 remained a most appalling personal loss for Ivanov: he lost his two most important people and friends in one month. On August 7th Alexander Blok died after a long illness, on August 26th Nikolai Gumiljow was executed by the Bolsheviks.

In 1922 the last volume of poetry written in Russia, Lampada (The Icon Lamp), was published. The open resignation, the misery about the past life, the powerlessness and anger over “vacuum, soulless ethers” moan from the “powerless” poems and did not go unnoticed by the Soviet criticism: “There is hardly anyone else, 1922 in Russia find a published book that would negate the revolution in an even more absolute, organic and irreconcilable way than 'Lampada' . ”Ivanov had little more than to look around to escape from the Soviet country.

On September 26, 1922 Georgi Ivanov left the country on the German ship "Kargo". In his memory ( essay ) Katschka (The Rocking of the Ship), he later vividly described his adventurous preparation and illegal departure from the Soviet country, as well as his desperation to leave Russia forever:

“Even if you disregard the waves, there was nothing pleasant about this trip. But on the contrary. Of course I smoked gold-tipped cigarettes, of course I was free, of course I was on my way to Berlin, to Paris, where I could do whatever I liked, where no one could unexpectedly arrest, banish or shoot me. Yes, everything was like that. But this realization was somehow pale, abstract, insubstantial, without value. Real things were: the rough wind, the wet deck, cloudy waves, and then the troubled question: is it possible that Russia will be lost to me forever? "

Emigration (1922–1958)

"Berlin, Paris and Nice's disdainful celebrities"

Georgi Ivanov stayed in Berlin from October 1922 to the summer of 1923 . There he initiated several new editions of his poetry: the books of poetry Weresk , Sady and his translation of the poem Christabel by Samuel T. Coleridges were published by the Berlin publishing house. Ivanov also published several anthologies by Zech Poetow , Gumiljow's estate, his last written poems. In November 1922 Ivanov traveled to Paris, where he visited his first wife and daughter Elena, met several well-known Petersburg poets, organized a literary evening in memory of Nikolai Gumilev's death. Ivanov donated the income from the editions of Gumiljow's estate and the literary evening to Gumiljow's widow Anna Engelhardt and her children, who lived in great need in Petrograd. In August 1923 Ivanov moved to Paris with Irina Odojewzewa (Iraida Heinicke, who had come from Riga in the meantime). From 1924 Ivanov began to publish his memories in the Paris magazines Zweno (1924–1927) and Poslednie Nowosti (1929–1930). In 1928, several essays were published in the book Peterburgskije simy (The Petersburg Winters ) with the subtitle "Memoirs". In 1952 the second improved edition of the book The Petersburg Winter was published by Chekhov Publishing in New York.

The Petersburg winters and other memories

In his memoirs, Georgi Ivanov was the first to describe the recent events in Russia, and he also described the surviving participants in these events, who he experienced in literary circles before and after October 1917. As he himself explained at the beginning: “The subject of my essays is the essence of literary Petersburg for the last ten to twelve years”, and how he participated in this life in Petersburg-Petrograd between 1910 and 1922. These are multifaceted reports on literary circles, as well as depictions of the terrible experiences after the “October Revolution”. With linguistic delicacy, Ivanov turns his reports into a captivating and exciting book of contemporary history. As Mark Aldanov wrote in his review of Ivanov's book in Sovremennyje sapiski (The contemporary notes (37), Paris 1928): “The genre of the book is difficult ... The author shows two epochs. People are bursting with fat, - people are dying of hunger, [...] Despite the accidental errors of memory or oversight, the picture given in Ivanov's brilliant book is 'historically true', even if much of it is for the majority of Petersburg was probably not known. "

Georgi Ivanov was known as a "sensitive observer", Alexander Blok already pointed out this Ivanov's ability, while Georgi made his first steps on the Peterburg literary stage as a young poet. Observing this talent and his ability to write are reflected in his memoirs and autobiographical essays. The passionately collected stories from one's own life and the life of others represent a clear picture of Russian history, which was very important in this respect and is still today, because these experiences offer a picture of the time of Russian culture and because the history of the Events back then had not yet been described in history books. Accordingly, it was the only possibility for his contemporaries and for future generations to present and record what happened. Some of Ivanov's thoughts about his colleagues are surprisingly accurate and show his ability for historical analysis and evaluation:

“The fact that 'Great Russia' lies in a coffin in Smolnyj in no way makes [the peasant poet] Kljuev sad at death or expresses his indignation towards the murderers from Smolnyj. Quite the opposite. More like joy - what had long been hoped for began to come true. The former Russia, albeit 'big' but belonging to the masters and the intelligentsia, 'not ours', finally died - served him right. And Lenin - today's murderer of the former Russia - is a suitable builder of the future. […] Sure: Lenin - a helpful person, a real one, ours. And to help him - is 'righteous', the duty of every farmer [russ. "Muschiks"].

Lord, protect freedom,

the red ruler of the commune!- then exclaimed Kljuew. And in those days it sounded to him, to Esenin and people who were spiritually close to them, and there were many of them, not absurd, as now, but like a solemn 'now you let your servant go in peace ...' "

In Ivanov's memories, the terrible images of everyday life in the days of "war communism" mix with the images of the happy days of the prewar times, the historical considerations and the evaluations of events, and thus they carry the authentic atmosphere of the time.

“Everyone was afraid of hunger until it 'seriously and for a long time' settled down. Then you stopped noticing him. People also stopped noticing the shootings.

[...]

Two philistines met, talked about everyday stuff and fell apart. Ballet ... fur coat ... the young Perfiriew and another student ... And here in the cooperative, herring was distributed today ... He will probably be shot ...Two citizens of the northern municipality talk about everyday life.

A citizen calls out to another citizen:

Citizen, what's for lunch today?

Have you registered, citizen or not? ...And they don't speak like that out of heartlessness, but out of habit.

The chances are also the same - today the student, tomorrow they. "

Georgi Ivanov was aware of the partiality of his memories and presentations and he prevented this with finesse by adding an artificial passage in the flow of his reports, which should show that the author is not entirely sure whether it is memories or dreams are. This grip, which he has already tried out in his poems, enables him to take a pause for thought or breathing space, which allows the reader a different point of view or allows the author a certain tense of the events, and at the same time averting the accusations of his contemporaries of falsity or distortion of the event . This section is even written in poetic form, or written as a piece of the prose poem, and was included as a foreign element in the flowing reporting of the experiences. These first samples in this genre are important insofar as they already point to the later important work of Ivanov's "Atomzerfall" ( Raspad atoma ).

“There are memories like dreams. There are dreams - like memories. And when you think of what was 'so recently, so infinitely long ago', you sometimes don't know what the memories and dreams are.

Well - there was 'the last pre-war winter' and the war. There was February and October ... And what was after October - there was also. If you take a closer look, however, the past becomes confused, slips away, changes.

… In the glass mist, over the broad river - the bridges hang, there are palaces on the granite bank, and two thin golden needle spikes shimmer faintly. Some people are walking in the streets, some events happen. Here the Tsar's chapel on the Marsfeld… and here the red flag over the Winter Palace. Young Blok reads poetry ... and a Blok 'turned to ashes' is buried. Rasputin was murdered last night. And this person who gives a speech (you can't hear the words, only a muffled roar of approval) - calls himself Lenin ...

memories? Dreams?

Any meetings, conversations - emerge from memory for a moment without context, innumerable many. Sometimes very pale, sometimes with photographic accuracy ... And again - glass haze, in the haze - Neva and palaces; people pass by, snow falls. The bells of the tower clock play 'If glorious ...'

No, the bells play the 'Internationale'. "

The turntable of the story turns almost in a flash: “Now there was a single echoing shot of the ' Aurora '” and it began “midnight throughout Russia”, everything “after February” repeatedly turned “by a full 180 degrees”. The events mix and can no longer be seen through. Everything happened so hastily and almost in an instant. Nonetheless, all of this is historical and was not invented by Ivanov. He presented his own perspective of the experience as an eyewitness, and if his language sounds too poetic, Georgi Ivanov was a poet. In any case, thanks to his gift, his memories are much more illuminating than any later written report of this kind.

Further memoirs are published under the title Kitajskie teni (Chinese shadows) and were only compiled as a unit by Ewgenij Witkowski. Ivanov also wrote many stories with a biographical background and individual essays as memories, such as the following: Newski prospekt (Newski Prospect), Brodjatschaja sobaka (The Stray Dog), Chekist Pushkinist (Cheka man as Pushkins connoisseur), Mertwaja golowa (Death's head) , O switskom poesde Trozkogo, rasstrele Gumiljowa i korsinke s proklamazijami (Trotsky suite train, Gumilyov shooting and basket with proclamations), S baletnym mezenatom w Tscheka (with Ballet patron in Tscheka) Farfor (porcelain), Katschka (rocking of the ship) and several others. As the last essay of this kind of memoir, rather even a historical summation of the events, Ivanov wrote Sakat nad Peterburgom (The Fall of Petersburg) in 1952 . In this memory Ivanov explained in great detail the course of the downfall of "marvelous Petersburg" and with it all of Russia:

“… In the

end, feel nothing but hatred for our fame and our state !

And then 'glamorous Saint-Petersburg' will no longer 'put itself on display' - 'it will be empty'.

Yes - what a strange business. As long as the Petersburg empire was ' showing itself off', as long as it was blossoming and growing stronger, the doubts about its future that saw the light of day with it also grew stronger. And quite the opposite, when it went faster and faster downhill towards catastrophe - committed these doubts to fade, evaporated, disappeared ...

Just before the end, those who still held the reins of the empire in their hands 'out of indolence' , as well as those who were ready to snatch them from their weakened, awkward hands, with an optimistic self-confidence. The throne of Nicholas II and the chair of the chairman of 'fat Rodzjanko', who was hated by the tsar, were both on the verge of disappearing into Tartaros when they suddenly seemed extremely stable to those sitting on it. Neither 'from the height of the throne', nor from the 'height of the lectern in the Duma ', nor from the comfortable work rooms of the leaders of the Cadet Party , nor through the uncleaned window panes of the conspiratorial apartments of the Social Revolutionaries was the deadly threat that overlooked all of them hovered over each one, no longer to be seen. Warring one another , the power, the legal, the semi-legal opposition and the revolutionary underground smugly agreed in the feeling of an 'unshakable stability' in the capital of the 'mother of Russia' , which they reined up for all eternity . "

In Kitajskie teni (Chinese shadow) individual memories are compiled which, like “Petersburg Winter”, summarize some of Ivanov's experiences in the years 1910 to 1922, which Ivanov himself published in Paris magazines, but did not include his “memoirs” in the book . Several very stimulating moments in Petersburg's literary life are described, how the St. Petersburg magazines functioned at the time, or how literary life developed after the “Great October”. This is how Ivanov describes the everyday life of his contemporaries in the famine years after the "Great October":

“At some point, studies will be published about the Petersburg 'House of Literature' from 1919–1922, perhaps even poems will be written. A few writers and journalists created a real miracle in the devastated mansion on the corner of Basseynaya and Ertelev streets. In the goddamn area of the 'Northern Commune', where there was nothing for people who could not or would not march in 'step with the proletariat' but lie down and die - a spot was created and screened off where they could not just find some food not only enjoyed relative warmth, but - and most importantly - were allowed to breathe. Behind the heavy door of the literary house, Soviet rule was, as it were, weakened. In a certain way, the frozen and hungry 'citizen', along with a portion of stockfish and millet porridge, also received a portion of spiritual and spiritual freedom that had been confiscated outside the walls of the literary house and declared illegal. For the hours he spent in the house - and many came in the morning and stayed until the end - he transformed from a Soviet anonymous into what he was before the 'Great October'. In a writer, minister, lawyer, painter, businessman, prince. Temporarily, for the duration of his stay under this roof, human dignity and freedom returned to the unfortunate St Petersburg honest man. And however important the daily bread may be, especially in those days - it was more important than the bread. "

In the "House of Literature" ( Dom literatorow ) Ivanov lets the reader empathize with the fate of the Russian intellectuals in hungry post-revolutionary Petersburg:

“A long line is reaching for the soup. With tin bowls and spoons in their hands, writers and professors stand like Spittelweiber. In the 'tail' you talk quietly.

A student standing next to W. Pjast gives him a German lesson. There is a plaid on Pjast's shoulders, the lower half of the suit - gray plaid - is much too expansive. He patiently repeats the vocabulary: Koschka - hangover, sobaka - dog… '

[…]

An infinitely long line stretches for the soup… Suddenly at the entrance - movement, noise, foreign talk. […] Well-dressed men give him [Chariton] a power of attorney - from the city council. Representatives of the British unemployed get to know the former Russian intelligentsia.

The unemployed from England are not only red-cheeked and well-dressed. You are cultured. They ask to know the names of the diners and at some they respectfully shout: ' Very pleased! 'After gazing at the auditorium and the library, they went to the canteen.

The gray-haired elderly gentleman who asked how they say 'grapes' in German has just received his bowl of porridge and is carefully carrying it to a table. His name, which is known throughout Europe, arouses the special interest of the English. They ask to be introduced, say some niceties, bow. The old man looks at her and blinks coolly with red eyelids. He doesn't care about niceties. He wants to eat. The porridge is getting cold. 'Dear Professor, - says one of the delegates, - allow us to taste some of the food that your esteemed government has provided you with.' The professor is hard of hearing and does not immediately understand what you want from him. When he realizes it, he grabs the bowl, presses it to his chest with one hand and raises the other protectively: 'My porridge, my porridge! Try the others! '"

Some contemporaries who were still alive reacted very sensitively to Ivanov's reports. Former ego-futurist friend Igor Severyanin was disappointed that he was not placed in the full radiance of his brief glory. Anna Akhmatova raged the most of the discontented, she got very angry with Georgi Ivanov, right from the start when he published the first reports in the journals of exile. Since Ivanov's representations were very anti-Soviet and Akhmatova stayed in Petrograd, one could consider her accusations as her own protection, but the campaign she started against Ivanov from April 1925 onwards remains incomprehensible. When you consider that the majority of contemporaries agreed with Ivanov's memories, and that research has identified them as an important source for the history of the period, their tantrums can only be explained for very personal reasons.

Georgi Ivanov also tried his hand at prose in 1929–1930 and published the novel Tretij Rim (The Third Rome) in Sovremennyje sapiski (1929 - Part 1; 1930 only excerpts from Part 2). Ivanov never finished the novel. As he later told his correspondent Vladimir Markov himself: "I wrote: 'Welsky started smoking a cigarette ...' and further, I don't know anymore ..."

After that, Georgi Ivanov wrote some historical essays on the subject of the last tsarist rule, which are later included in a book Kniga o poslednem Zarstvowanii (The book on the last tsarist rule). From 1933 these essays were published as individual parts in the newspaper Segodnja (Today) in Riga. Some researchers interpret this as an indication of an extension of Ivanov's novel Tretji Rim (The Third Rome), which is not convincing for reasons of content.

Georgi Ivanov was first and foremost a poet, and only as such did he see himself. And so his first volume of poetry appeared in Emigration Rozy (Rosen) as early as 1931 . After the publication of the volume, Ivanov was hailed as “the first poet of emigration”.

Poetry book roses

We stroll absent-mindedly through the streets,

we look at women, we sit in cafes.

But we don't find the right words,

and we don't want the approximate words anymore.

What do you do? Return to Petersburg?

Fall in love? Or blow up the opera?

Or just lie down in a cold bed,

close your eyes and never wake up ...

The motifs from this poem were repeated and deepened by Ivanov in his later work "Atomzfall" ( Raspad atoma ), as well as the following poem:

The soul is numb. And more callous every day.

- I'm going to die. Give me your hand No Answer.

I still listen to the rustling of the branches.

I still love the play of light and shadow ...

Yes, I'm still alive. But what do I get

if I no longer have the power

to unite in one consciousness of

the beauty of the tattered parts.

Ivanov was not only praised for his peculiar poetry, there were also pessimistic tones. Gleb Struwe branded Ivanov as a nihilist in his book Russkaja literatura w isgnanii (The Russian Literature in Exile, 1956) because of the poem Choroscho, tschto net Zarja . This question of nihilism still divides the opinion of Ivanov researchers to this day. It was probably not noticed by everyone that while Ivanov's negations are one of the most common words, his negations say the opposite, they are more affirmations than nihilistic negations.

It's good that the tsar doesn't exist.

It's good that Russia doesn't exist.

It's good that God doesn't exist.

Only a yellow

glimmer of the sky, Only icy cold stars,

Only millions of years.

[...]

“Don't be fooled by the pessimism and nihilism label that has been attached to the poet: Who writes with this linguistic purity and musicality about what he - only him? - under pressure, he cannot be a negator, at least not in the narrow interpretation of this word! Those who accuse him of this should first look carefully at what this poet denies, and above all, how he denies it. He keeps the strict traditional forms of poetry in a perfectly beautiful, artistic language in order to speak of the meaninglessness and ineffectiveness of beauty and art: the end of art is thematized with the utmost artistic will. "

Before you die,

you should close your eyes.

Before you keep silent,

you should talk yourself out of it.

The stars break the ice,

The spirits rise from the bottom -

Too fast comes the

too tender spring.

And touching

triumph, turning to triumph,

the words fall apart

And mean nothing.

Or:

This is the

ringing sound in the distance, This is the Troika broad corridor,

This is the black music Bloks, That

falls on the shining snow.

... Beyond the boundaries of life and world,

In the vastness of the icy ether

Will not part with you in spite of everything!

And Russia like a white lyre,

Above the snow-covered fate.

Through Europe by car

In the 30's, the Ivanov family often traveled to Latvia, where Iraida's father Gustav Heinicke (1863–1933) lived. You like to be in Riga , sometimes on the banks of the Jūrmala in the newly founded Baltic state of Latvia . In 1933 they even lived in Riga for almost a year: Gustav Heinicke, a well-known lawyer and Ivanov's father-in-law, was dying. In September of the same year, Ivanov had the opportunity to travel through Europe by car with Latvian friends. Immediately afterwards, he described this trip in several reports, which he then published from November in the magazine Poslednije Novosti (from November 3, 1933 to March 16, 1934). As an "excellent observer" (A. Blok), Ivanov recognized the fateful developments in Europe as early as 1933 and foresaw Germany's terrible path through National Socialism. Already at the Lithuanian-Prussian border crossing he noticed some features of the coming years: “the hundreds, thousands of very small to huge flags”, the “festive atmosphere” during the ordinary day, the red flags with black swastikas everywhere the National Socialist Party came to power.

Then in the Polish-German border town of Schneidemühl (today Piła , Poland) the situation becomes even clearer. Ivanov met a man who confided in him his unfortunate fate:

“When he sat down with me, I was reading a Russian newspaper. - Russian? - he asked softly in German and looked at me sideways, then looked away again. And added even more quietly: - Jew?

When he heard that yes, 'Russian', but no, not 'Jew', he backed away and blushed: - 'Oh, forgive me, forgive me! ...'

I hurried to assure him that I was from 'areas and I am circling where there is no such thing - and apologizing that he thought I was a Jew was utterly inappropriate.I did not finish my explanation. This lumbering, respectable, well-dressed man's face twitched, his eyes big and round. Slowly a tear crept from under his right eyelid, as heavy as he was, and rolled down the tie.

- 'My God, - said he, - my God! From such areas, from such circles ... France, Latvia. Yes! No smear campaign, no racial hatred ... My God! I long ago forgot that such areas existed. ' - The tears rolled down his fat cheeks [...] "

The journey by car - it was the American upper-class model from the Stutz brand - was long and ran right across Germany: Berlin and Potsdam, Halberstadt and Harz, then lunch at Baron “N” [identity not established] in a medieval one Castle in Westphalia :

"Hitler's teaching is so high that a simple mortal cannot understand it ..." - this is how the lord of the castle, Baron "N", instructed his guests, who was once lieutenant "the White Cuirassier of the Imperial Guard", then in the 20s and 30s in Berlin banker, was on the board of directors of a bank, as well as part owner of a well-known department store, and has now become co-owner of an important "cinematography company".

"Hitler - German Messiah ..." - murmurs Baron's wife, a Russian who Georgi Ivanov had known since childhood.

In Göppingen the travelers are so tired of the onward journey due to the excess of boys in brown uniforms that instead of visiting other interesting cities in Germany as planned, they broke off their trip prematurely and drove directly to France.

These reports were only compiled by Evgeny Witkowski in 1994 (on the occasion of Ivanov's 100th birthday) as a unit under the title Po Evrope na awtomobile (Through Europe by Automobile). So far they are still up-to-date today and not only important for historians, because they were written in the autumn of 1933 with the fresh impression of a keen observer who was also an outsider. In these reports, the other side of the “coin” is formulated in a far-reaching manner, the side of the event that could not be perceived from within and was not properly recorded at the time. Ivanov's observations and reports were then still intended as an emphatic warning to his own compatriots in exile about the development of National Socialist Germany and should be perceived as such. The Russian emigrants did not take this threat seriously, many were Russian Jews and later paid with their lives.

Book of poems Embarkation for the island of Kythera

In 1937 Georgi Ivanov published his last book of poems, Otplytie na ostrow Cytera (Embarkation for the Island of Kythera), written before the Second World War . At first glance, the title of the volume seems similar to the almost identical title of Ivanov's first volume of poetry from 1911. Only the content of the poems no longer points to the romanticism of the young, rather the dreary thoughts of a stateless emigrant. As for the title of the volume of poetry, Ivanov himself points out in a later poem what he meant by this second Kythera .

I no longer fear it. I feel dreamy.

I'm slowly flying into the abyss.

I don't remember your Russia and I don't

even want to remember.

[…]

… I see from the stage to the parquet

A glow… Giselle… clouds…

The embarkation for the island of Kythera,

where the Cheka is waiting for us.

The morbid tones of the volume of poetry reveal Ivanov's doubts about any prospect of being able to see his country at some point. It's like saying goodbye to earlier dreams that “the Bolsheviks will soon, very soon perish”. Twenty years after the “Great October”, their own predicament also became clear in the emigrant circles: Soviet rule exists and life in the Soviet country goes on, and without those who have left the country.

Russia is luck. Russia is light.

Maybe Russia doesn't even exist.

And the sunset never went out over the Neva,

And Pushkin never lay dying in the snow.

And there is no St. Petersburg, nor the Kremlin -

only snow, snow, fields, fields ...

snow, snow, snow ... And night is long,

and the snow will never melt.

Snow, snow, snow ... And night is dark

And it will never be over.

Russia is silence. Russia is dust.

Maybe Russia is just horror.

Ropes, balls, icy darkness

And music that robs the mind.

Ropes, balls, sunrise in the forced camp

About what in Welt doesn't have a name.

Hence the almost philosophical considerations in Ivanov's poems, which were supposed to show only one thing, the deep despair at the meaning of the life and existence of a homeless person. As a result, the tone of the poems, the reflections on “the good and the bad”, but also the atomic decay that follows this volume of poems seems very gloomy.

Neither in the clear name of the gods,

nor in the dark name of nature!

...

Trees still rustle on these shores , the waves

splash ... The world melts like a candle,

And the flame scorches the fingers.

Resounding in immortal music, it

gains in breadth and perishes.

And the darkness is no longer darkness, but the light,

and the yes is no longer a yes, but a no.

... And nobody gets up from the grave,

And gives us back our freedom -

neither in the light name of the gods,

nor in the dark name of nature!

It's adorable, this haze.

It resembles a glow.

Good and bad, good and bad,

Therein the inseparable fusion.

The

minds of good and bad, of good and bad , heated to the point of white heat.

This volume contains the same sounds and motifs, which can only be heard in full expression in the work Raspad atoma (atomic decay). Ivanov addresses his “dear contemporaries” almost ironically, who have no idea what you can do with these words. Only after the appearance of the “atomic decay” will one fully understand the finesse of this poem, which probably corresponds best to the expression of Russian Toska at this point.

The stars are blue. The trees sway.

Ordinary evening. Ordinary winter.

Forgive everything. Nothing will forgive.

Music. Darkness.

We are all heroes. We are all traitors.

We believe all words equally.

Well, dear contemporaries,

do you feel happy?

Raspad atoma (atomic decay)

Ivanov's next book, Raspad atoma (atomic decay) , was published in December 1937 . The front page says 1938, but already in December the book was enthusiastically received at several Sunday meetings with the Mereschkowskis ( Dmitri Mereschkowski and Sinaida Hippius had run a literary salon on Sundays in their Paris apartment, where the young poets gathered for a literary society) and then discussed in the meetings of the “Green Lamp” on January 28, 1938. Mereschkowski called “Atomzfall” a “brilliant book” and Sinaida Hippius gave a lecture in the Green Lamp , which she then published under the title Tscherty ljubwi (The Signs of Love) in Almanach Krug (The Circle). A detailed article by Vladislav Khodasewitsch in the magazine Sowremennye zapiski (The contemporary notes) will follow in January . Otherwise, Ivanov's book was surrounded by a “wall of silence”. Ivanov's contemporaries did not understand this work and did not understand the message of the book. Only Leo Shestov was the only one who recognized the groundbreaking ideas in Ivanov's work at that time. He called atomic decay an existentialist book and called Georgi Ivanov an "existentialist".

Leo Schestow was busy with the philosophy of Kierkegaard at this time, he even gave his lectures in the Sorbonne on the "religious philosophy of Kierkegaard", especially since Kierkegaard's ideas and existential philosophy were almost unknown in France at the time . Schestov's philosophy itself also belonged “to the type of existential philosophy”, so it was no problem for him to recognize the true meaning of Ivanov's work. He noted, however, that Ivanov was by no means a “religious existentialist”. Certainly Georgi Ivanov cannot be called a philosopher either. Ivanov's work, though shaped by deep philosophical thoughts, was primarily a literary work, even a highly poetic work, which was written as a long prose poem . Ivanov did not choose the genre of the work by chance. Charles Baudelaire already described this genre as a highly sought-after type of poetry. In a letter to the publisher Arsène Houssaye , Baudelaire mentioned the merits of poetic prose:

“Who of us has not dreamed of the miracle of poetic prose in our days of ambition, which without meter and rhyme would be so full of music, so supple and exciting enough to be able to absorb the lyrical movements of the soul, the waves of dreams and unexpected leaps of consciousness to transform? Above all, the traffic in the huge cities and their countless, overlapping relationships create this seductive ideal. "

Therefore Georgi Ivanov received two highest honors for the work Raspad atoma (atomic disintegration ) at the same time: he created a highly poetic work in a desirable kind of poetry, and at the same time a completely new work on the rank of the time, that meant a poetic work with new ones philosophical-existentialist thoughts. Earlier philosophers and great writers had already established that human existence was without any meaning. Arthur Schopenhauer was already of the opinion that the meaninglessness of life could only be overcome through the “illusion of art”. Georgi Ivanov disillusioned this Schopenhauric thought in which, looking at his own time, he noticed a tragic change in the way of thinking and attitudes towards literature and art:

“You can describe tonight, Paris, the play of light and shadow in the feathered sky, the play of fear and hope in the lonely human soul. It can be done cleverly, talented, pictorially, believably. But one cannot work a miracle - one cannot pass the lie of art for the truth. A short while ago it was still successful. And now ...

What was successful yesterday became impossible today. One cannot believe in the appearance of a second Werther , through whom enthusiastic shots of fascinated, intoxicated suicides ring out all over Europe. One cannot imagine a little book of poems through which a modern person would wipe off the tears that came out of their own accord and look at the sky - just such an evening sky - with oppressive hope. Impossible. So impossible that it's hard to believe that it was once possible.

[...]

I envy the writer who hones his style, the painter who mixes the colors, the musician who sinks into the sounds, all those [...] who believe that a plastic reflection of life is at the same time its overcoming be. If there was only one talent, a special, creative restlessness of the mind, the fingers, the ear, one only needs something from the imagination, something from reality, something from sadness, something from the dirt, to take it with you To decorate style and fantasy, […] and the deed is done, everything is saved: the futility of life, the futility of suffering, loneliness, torment, sticky, nauseating fear - have been transformed by the harmony of art. "

Ivanov no longer believes in the redemption of human existence through art. Sinaida Hippius admires the expressiveness of Ivanov's portrayal of the withering of art:

“I don't know who among the writers could have shown with such force the withering away of contemporary literature, of all art, its nullity, its impossibility. The book doesn't want to be 'literature'. According to its immanent meaning, it breaks through the 'boundaries of literature'. Written, however, it is like a real literary work of art - and that is important: If it were written faintly and colorlessly, we would simply ignore what our contemporaries say, think and feel. "

But Ivanov touches on the subject of the withering of art only incidentally, with only one purpose, to show that there are nevertheless new ways for literature. Literature no longer needs sweet lies, no made-up fairy tales, it should not teach and no longer gloss over life. Literature should be just as merciless as life is merciless, the search for eternal truth is pointless and there is only one truth: the moment you are living through.

"- Wait. Do you know what it is This is our unique life. At some point, in a hundred years, a poem will be written about us, but it will only contain sounding rhymes and lies. The truth is here. The truth is this day, this hour, this slipping moment. "

That is why he tried to capture these fleeing moments, which only represent real life, on paper and to express them in simple words. Ivanov relentlessly and honestly displayed the appalling contradictions of human life: the timeless questions of love and the eternal questions of death, the alienation in times of complete loss of faith in every sense. The momentous seizure of the consciousness of complete loneliness of every single person is a guiding principle of the entire work, the total abandonment and thus the following alienation brings Ivanov to the highest level of understanding and shows that if there were a way out of the absurdity of existence, out of the To save oneself from definitive spiritual decay, a free decision about one's own death would be the right one. But Georgi Ivanov only leads the thoughts of his hero to the allegedly “inevitable” final frontier, to suicide, only to find out that this too is exactly the same absurdity as life itself, and that there is only one path left :

"Stride through life like an acrobat on a tightrope, through the unsightly, disheveled, contradicting shorthand of life."

Especially since everyone is somehow a part of the "deformity" that is ruling the world right now, it makes no sense to expose them:

“Even part of the deformity of the world - I see no point in blaming it. I would like to add, paraphrasing the words of the newly wed Tolstoy : "That was so senseless that it cannot end in death". I now understand this with astonishing, inevitable clarity. "

“Atomic decay” can be understood as a brave excursion to the abyss of human consciousness, where the picturesque images of Paris mix with historical allusions, thoughts about “fading world ideas” and about the meaning of life in general and merge with vicious fantasies.

Sinaida Hippius immediately suspected that the book could not be for everyone and that it would only be understood later.

“A Russian man is walking the streets of Paris. [...] He hardly differs from his contemporaries, at least he shouldn't be different from them; its uniqueness lies only in the fact that it can bring the hidden to light, opens up, reports in its own, as precise words as possible about itself and the environment, about how it sees or sees you and yourself in the moment.

This is the whole booklet “Raspad Atoma” by Georgiy Ivanov. Nothing appears to be happening in it, but in reality something so important is happening that it is more significant than any adventure, no matter how intricate.

[…]

Remarkable: Nothing new is revealed in the book, it only reveals the eternal in a new way. [...] The openness, the undisguised, fearless description of the hidden in the choice of words, of the secret desires of many, naturally turns out to be an obstacle between the book and these many: They by no means want their secret desires to be exposed.

[…]

And not only these descriptions alone, the whole linguistically exact way of writing has to meet human protective walls that make it difficult for the book to penetrate the big wide world.

[...]

The hero of the book knows, because he is a modern person! If I am not mistaken, he says on the first page: “I want to overcome the hideous feeling of numbness: the people have no faces, the words have no sound, everything lacks meaning. I want to smash it… ”

[…]

I do not make any concrete conclusions, but I would not be surprised if the book we are talking about turns out to be the voice of a preacher in the desert today. In the end, it's not that important. The important thing is that it is there, that it was written; and if it is true that “life begins tomorrow” - the person living tomorrow will say: Not all books written in emigration crumbled to dust; here is something remarkable that remains and will remain. "

Georgi Ivanov himself valued the book very highly, it was his "favorite work" and he repeated several times to his correspondent that it was "the best thing I have ever written".

"Man, little man, Zero looks helplessly ahead of himself. He sees black emptiness and in it, like fleeting lightning, the incomprehensible essence of life. A thousand unnamed, unanswered questions, illuminating for a moment through fleeting fire and devouring at once through darkness.

Consciousness trembling, powerless, looking for an answer. There is no answer to anything. Life asks questions and does not answer them. Love asks ... God asked man - through man - questions, but did not give the answer. And man, only to ask more predictively, less able to answer nothing. Eternal synonym of failure - answer. How many wonderful questions have been asked in the history of the world and what answers have been given ...

Two billion inhabitants of the globe. Everyone is entangled in their agonizing, unrepeatable, equal, useless, disgusting complexity. Everyone, like the atom in the core, trapped in the impenetrable armor of solitude. Two billion inhabitants of the globe - that is two billion exceptions to the rule. But at the same time the rule. All adverse. All unhappy. Nobody cannot change anything and understand nothing. My brother Goethe, my brother Concierge, you both don't know what you are doing and what is life doing with you.

Dot, atom with millions of volts flying through its soul. They are about to split them. Immediately immobile powerlessness frees itself through terrible explosive power. The same. Earth was already shaking. Something was already creaking in the pillars of the Eiffel Tower. Samum began to swirl cloudy strands in the desert. Ocean sinks ships. Trains derail. Everything tears, slips, melts, crumbles to ashes - Paris, street, time, your figure, my love. "

When Ivanov wrote his work, there were only initial attempts to split an atomic nucleus , there was no talk of nuclear weapons or even atomic bombs. But it seems that Ivanov had foreseen his time, in his work Raspad atoma (atomic disintegration ) he lets the “atom” split and triggers an atomic quake, as it actually happened later.

The masterful mixing of themes and motifs, the amalgamation of the conscious and the unconscious, the mercilessness of the representations should contribute to the renewal of literature. However, the first existentialist-poetic work went completely unnoticed due to the language barriers and the isolation of exile literature .

“What are we staying with?

[...] With the clear realization that you cannot save anyone and that there is nothing to console you. With the feeling that one could only penetrate the truth through the chaos of contradictions. That even reality cannot be trusted: a photograph lies, and every document is falsified from the outset. That everything average, classic, forgiving is unthinkable, impossible. That the sense of proportion slips like an eel from the hands of those trying to catch it, and that this incomprehensibility is the last of their remaining creative abilities. That when you finally catch it, the catcher holds onto a bad taste. "In his arms the child was dead." That everyone around hold these dead children in their arms. That everyone who wants to penetrate through the chaos of contradictions to the eternal truth, at least to its pale reflection, has a single path: like a circus performer on a tightrope over life ... "

And so later, Ivanov's contemporary Juri Terapiano wrote an important remark about "atomic decay", although not until after Ivanov's death:

“Long before Sartre , almost all of 'Sartreism' was revealed in Raspad Atoma . But only S. Hippius and D. Merezhkovsky dare - unlike Milyukov and Chodasewitsch - to describe the book as outstanding example of modern man. Georgy Ivanov exposed the disintegration of the soul that was so characteristic of the post-revolutionary epoch. He raised the problem of the tragic state of modern man to the rank of poetry and thus gave it a new note. [...] he created the new shudder ( frisson nouveau ) and brought the world feeling of the post-revolutionary generations to the day "

Georgi Ivanov later wrote a single poem on the subject of "Atom", but only after the great catastrophe of World War II.

There will be no Europe, no America,

no parks in Carskoe Selo, no Moscow -

attack of atomic hysteria

Will dust everything in a blue glow.

After that,

a light-permeable, all-forgiving plume of smoke will gently stretch across the sea ...

And he who could help and did not help

will remain in prehistoric solitude.

After the publication of Raspad atoma ( Atomic Decay ), Georgi Ivanov did not write anything for almost seven years, until the end of the Second World War. There is a thesis in research that Ivanov wanted to put an end to this work, so to speak “the end of his own poetry”. This thesis is contradictory and therefore controversial. Initially, Ivanov himself knew that he was creating a highly poetic, contemporary and modern work, that this work was "the best" that he ever wrote, as he later assessed himself. One can rather speak of a “ keystone ” that crowns his poetry. However, since not all of his contemporaries understood the work, this could have so astonished him that he no longer wanted to write “for dumbbells” afterwards. However, one must also take into account that the Ivanovs were busy buying a villa and moving to Biarritz shortly after the work was published. In addition, the Second World War began a year later.

Biarritz and Paris. After the Second World War

In May 1938, the Ivanovs bought a villa on the Atlantic coast in Anglet near Biarritz. In addition, an apartment in Biarritz itself, “two steps from the seashore” on Avenue Edouard VII. In 1933, Ivanov's wife received a magnificent inheritance after the death of her father. The couple moved into one of the most expensive arrangements from Paris and looked around for further investments.

So from May 1938 and then throughout the summer they were continuously on the Atlantic coast, and from July 1939 to 1946 they lived permanently in Biarritz, traveling to Paris only occasionally. At that time the “crème de la crème” of the Russian aristocracy lived in Biarritz: the families of the Grand Dukes Galicin, Gagarin, Naryschkin, Obolenski , Yusupov and others.

And so the Ivanovs also led a glamorous life on the Atlantic coast. The apartment on Avenue Edouard VII was in the Rocailles district, the aristocratic district of Biarritz, and the villa “ Parnass ” on the golden beach in Anglet, only a few kilometers from Avenue Edouard VII. The newspaper "La Gazette de Biarritz" reported repeatedly in the "Carnets mondains" section about "cozy" receptions at the Ivanovs. Ivanov's wife, the English generals, gathered around them for their bridge evenings, and the Ivanovs often screened the latest films, such as film adaptations by Countess Regis de Oliveira about Brazil and the Basque Country.

Such tea receptions and bridge evenings, as well as the receptions of Grand Duchess Cetlin, but also the lifestyle of full enjoyment were strange and incomprehensible to the art-making contemporaries, so that on the part of some literary colleagues towards Ivanov something like skepticism and sometimes even a kind of envy arose.

The visits to "Cinema" and parties at the English consulate, as well as the own receptions, came to an end with the German occupation of Biarritz on June 27, 1940. (Paris capitulated on June 14th, and then officially all of France on June 22nd.) Ivanov's villa "Parnass" in Anglet was requisitioned by the Wehrmacht for military purposes in 1943 and bombed by the British in March 1944 as a German military object. Latvia, where Iraida Heinicke still had sources of income from several manor houses, was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939 and her property was declared public property. All reserves, such as money, gold and securities, were already used up during the war and were no longer sufficient for their usual chic life. However, the real material problems for the Ivanovs did not start until 1948.

The emigration magazines in Europe were almost all destroyed after the war. That is why Ivanov published his first poems after the war from 1945 in the Parisian pro-Soviet magazine Sowetski patriot (Soviet Patriot). However, those of his poems have no political content. He then published in the Almanac Orion (Orion) from 1947 , from 1950 Ivanov worked as the head of the literature department in the Parisian magazine Vosroschdenie (The Rebirth), where he published some reviews, essays and stories, including some poems that would later be in his next volume of poetry were recorded:

Nothing can be undone. Yes and what for?

We forgot to love, we forgot to forgive,

We never learn to forget ...

The strange land sleeps

quietly, the sea rushes steadily. Spring begins

in this world in which we torment ourselves.

His next poem was also published in Wozroschdenie in 1949, after which it was included in the poetry book Portrait without Similarity . In May 1950 Georgi Ivanov published his first volume of poetry after the war, Portret bes schodstwa (portrait without resemblance).

Now you will not be destroyed

As that mad leader dreamed of.

Fate will help, God will help,

But the Russian man is tired ...

Is tired of suffering, is tired of being proud,

Pushing his head against the wall in masses.

It's time to enjoy oblivion,

maybe it's time to let yourself be wrecked.

... And nothing will rise.

Not under the sickle, not under the eagle!

From there 1951gelang Ivanov his poems in the magazine Novy schurnal to publish (New Journal) in the US for a better fee. The following poem was first published in New Journal in 1951 , and then included in the collection of poems 1943–1958 Stichi (1943–1958 poems):

I'm told you won the game!

It does not matter. I don't play any more.

As a poet I may not die, but

as a person I am dying.

Accustomed to a prosperous life, the Ivanovs were no longer satisfied with the income from the publications: The cost of living in France was made more difficult by the high prices of almost everything, especially food and medicines; Ivanovs moved from one hotel to the next, and if there was money they went straight to a better hotel, the two of them obviously couldn't handle their income. And so they constantly begged for money from various associations and sponsors. In 1952 Ivanov published a second edition of his memoirs of the Petersburg Winter in the USA. He received a good fee from the Chekhov Publishing House (New York), Ivanovs immediately moved to the “Haute Maison” castle in Sucyen Brie, later to the “Russian House” in Montmorency north of Paris, and from 1954 both lived in the “Luisiane” hotel “In the center of Paris.

Fateful for both of them, there was also a serious but unfounded accusation that only turned out to be a misunderstanding, even a deliberate defamation, much later after Ivanov's death: Ivanov had collaborated with the Germans during the occupation. The trigger for this fraudulent accusation was Ivanov's former friend Georgi Adamowitsch, who organized a bridge (!) Reception with the newspaper clipping from La Gazette de Biarritz that was sent to him with the report on a bridge reception by the generals (English!), Ivanov's wife the German generals reinterpreted. The vague rumor of the alleged collaboration of Ivanov spread willingly in the émigré circles, who had always viewed his luxurious life with disapproval. It was only a few years ago that the Petersburg Ivanov researcher Andrei Ariev succeeded in meticulously analyzing the data of the reports in Carnets mondains to unequivocally refute the accusation by referring to the time of the English stay in Biarritz and the time of the German occupation with the newspaper article in question about alleged bridge receptions for the "German generals" compared.

Ivanov had to explain this to his colleagues for a long time after the war. He was almost expelled from the Writers' Union, and as a result, he and his wife were not given any material or financial support from the associations or any help from abroad.

These years after the Second World War were the most horrific years for the Ivanovs, at least that is how Ivanov's widow Iraida Heinicke (known as Irina Odoewzewa) later described this time in her memoirs Na beregach Seny (On the banks of the Seine). This is how their so-called “poverty” began: Because they were too relaxed with their money as soon as something was there, both of them lived at their finest, and at the same time the support from the aid organizations was lacking, so their situation became unfortunate. Fortunately, both of them soon got a place with a free stay in one of the senior citizens' homes that were made available by the French state for the needy Russian nobility.

Hyeres. The last years of life. Poems from Dnevnik and Posmertnyj dnevnik

From January 1955, the Ivanovs received a place at the expense of France in the “Beau-Séjour” retirement home in Hyères , on the Mediterranean coast. In a letter to Roman Gul, Ivanov wrote the following about her new home: “But, finally, the thing is over and we are in the south: sun, sea and a free roof over our heads. I very much hope that I will come to my senses here after the life in Paris of recent times, which, to put it simply, was unbearable ... "

The "Beau-Séjour" house was in the center of Hyères on 1 Avenue du XV Corps and was formerly the "Grand Hotel Beau Séjour", which had recently been reorganized for charitable purposes. The property, surrounded by a large park, mostly blue skies, Mediterranean warm weather and the lingering green of palm trees, pines and oleanders, the scent of mimosa and almond trees initially affected Ivanov's feelings of having arrived in paradise: “In the shade 29ºC , in the sun 40ºC. Wonderfully fresh, but not hot. Hyères is not a small town, it was a splendid residence of Queen Victoria. It was from here that Saint Louis started his crusades. [...] Among the clients of the "Beau-Séjour" is Count Zamojski, who stranded here directly from the marble halls of his castle in Warsaw. [...] Also the other counts and princes: fine bridge evenings, hand kisses ... ”wrote Ivanov in the next letter to his correspondent Roman Gul.

So it is not surprising that Georgi Ivanov wrote his passionate, heart-moving poems during this time. The cycles of poems from the Dnewnik (The Diary) and Posmertnyj dnewnik (The Posthumous Diary) were created in Hyères , which Ivanov first published in the New Journal in the USA. Then the poems appeared in an anthology 1943-1958 Stichi (1943-1958 poems) in New York in September 1958, two weeks after the death of Georgi Ivanov. From the Dnewnik (The Diary) cycle , the poem Na juge Francii prekrasny (Wonderful in the south of France) is worth mentioning, which Ivanov himself described as important in a letter to Vladimir Markov:

Wonderful in the south of France

The Alps Cold, the gentle heat.

The yellow-red clay soil hisses

under an amethyst-colored wave.

And children gathering the crabs,

laughing to jellyfish and waves,

approaching the gate to the paradise of

which we only dream.

The coolness of the arm of the Luna sparkles

with stars on the

armlets,

And the violet summer

is certain to us - as long as

In the rays of blooming and withering,

In the ornament of foam and ivy,

eternal suffering shines ,

With the wings of the seagulls fluttering.

The next poem can also be named as indicative of Ivanov's "diary":

There aren't even expensive graves in Russia.

Maybe there were once - I've forgotten.

There is no Petersburg, no Kiev, no Moscow -

maybe there was once, but unfortunately I forgot.

The two poems clearly convey the mood of the poet. On closer inspection, the motifs in Ivanov's poems from this period are analogously the motifs from the work Raspad atoma (atomic disintegration ): " Senselessness of life, futility of suffering, loneliness, torment, sticky, nauseating fear". However, compared to the time when he wrote Raspad atoma and created everything from his imagination, the motives for such thoughts were now much closer to him: He got sick, felt lonely and abandoned, cut off from literary life, living far away from Paris. Despair, which he used to regard as a "game", has now become an everyday reality for him:

I made despair a game -

why the sighing and crying, indeed?