History of Zimbabwe

The history of Zimbabwe describes the history of the territory of what is now the state of Zimbabwe from the beginning to the present day.

Stone age

Until the turn of the ages, today's highlands of Zimbabwe were inhabited by Stone Age hunters and gatherers who belonged to the Khoisan peoples. Their late Stone Age culture differed from the Neolithic in other regions in the complete absence of pottery, agriculture and livestock. The Khoikhoi only took over these from the Iron Age immigrants, the San .

Iron age

Research problems

Written records have only been available since the arrival of the Portuguese around AD 1500. Older Arabic records from the region exist, but the most important author, Al Masudi, probably only noted in the 10th century what was reported to him on the coast about the hinterland. Therefore, what happened before was mainly reconstructed from archaeological finds, which are more reliable than oral tradition.

All-African context

According to archaeological finds, iron smelting was invented in Africa in the Sahel zone and then taken over by the Bantu in what is now Cameroon and carried with their expansion into eastern and southern Africa. It arrived on the Zambezi and Okavango in the centuries around the turn of the times. In addition to this picture, which is then shown in more detail, there is also the view that the Bantu did not reach the Zambezi until the turn of the first to the second millennium. According to both theories, the highlands of Zimbabwe were populated by Bantu when Greater Zimbabwe had its heyday between 1200 and 1450 .

Early Iron Age culture

Around the turn of the ages, the Bantu peoples from East Africa began to spread south across the Zambezi. They brought with them an early Iron Age culture, which also included pottery, agriculture and cattle breeding, but mainly sheep and goats, hardly any cattle. Mabveni , the first Iron Age settlement from the late 2nd century, was found in the highlands of Zimbabwe. By 1000 AD they had extended to the entire highlands. During the Bantu immigration, Khoikhoi resident in the area appear to have taken over cattle-raising from them.

Iron Age culture

A second Bantu immigration with a more advanced Iron Age culture left traces on the upper Zambezi in the middle of the first millennium. These people seem to have moved west of the Zimbabwe highlands past the Limpopo . A culture with large settlements of several thousand inhabitants (including Musina ) emerged there in the 9th and 10th centuries . Shortly before the turn of the millennium, this culture experienced a decline, possibly due to ecological exhaustion of the region. Apparently, a large part of the population left the Limpopo area and spread from the southwest over the highlands of Zimbabwe in the 10th to 15th centuries.

They are considered by several, but not all, historians to be the ancestors of today's Shona, who make up roughly 80% of today's population. They brought a culture of the later Iron Age with them and, in addition to farming, practiced cattle breeding on a large scale. On the edges of the highlands, cattle breeding led to transhumance . The city of Zimbabwe and other permanent settlements were on the less malaria-infested highlands, where agriculture was practiced in the summer rainy season. In the dry season, the cattle were driven into the sparsely populated lowlands wherever possible, where there was plenty of dry grass.

port city of Cefala = Sofala,

Manich = Manica,

Simbaoe = Greater Zimbabwe ,

Zuama = Zambezi; almost all of Africa's major rivers flow from the same central lake in this map.

Several states emerged partly one after the other, partly in parallel. Greater Zimbabwe near Masvingo , the largest complex of old stone buildings in Africa south of the equator, is regarded as the first center of the Mutapa Empire, whose power then extended to the coast and also went north and south beyond what is now Zimbabwe. Khami, a similarly large complex of walls seven kilometers west of Bulawayo, was initially built in parallel and later became the center of the Torwa Empire .

Greater Zimbabwe was abandoned around 1450, probably because the population had drained the country. The Mutapa state shifted its center north and lost its supremacy to the Torwa state. The capital Khami became the new center for about 200 years . In the middle of the 17th century, the Torwa state was taken over by the Changamire dynasty. Shortly before or after that, Danangombe (Dhlodhlo) became the capital.

The Shona states had lively trade relationships with Swahili- speaking traders along the Indian Ocean coast . They exchanged gold , ivory and copper against cloth and glass , the foreign trade reached to China (archaeological finds). There was a local textile production and its products were very prestigious. However, because of the use of looms, which were technically outdated compared to other contemporary models, this could not hold its ground against the competition from imported cloths.

Modern times

During the 15th century, Islamic and Portuguese traders competed for influence in the royal courts. When Portugal made the Mozambican coast its colony and cut off the Swahili coastal trade, the Shona Empire lost its leading role. In the 17th century, the Nguni peoples , who came from the Congo area and were strictly organized in military terms, immigrated to the area south of the Zambezi, best known the Zulu in South Africa. In today's Zimbabwe, it was the Nguni people of the Ndebele (Matabele) who conquered the country in 1835 under their King Mzilikazi and subjugated the Shona. The last Shona state of the Changamire dynasty was weakened by civil wars and was simply passed over by the new political actors, both African and European. The area of the Matabel area was almost congruent with that of today's Republic of Zimbabwe. The capital was Bulawayo .

Colonial rule

Since the establishment of their settlements on the coasts of Angola and Mozambique, the Portuguese had claimed the inland areas of southern Africa from the west to the east coast without seriously enforcing this claim to power. In the 19th century traders, hunters and missionaries of the British (see David Livingstone ) and Kapholländer ( Boers ) questioned the Portuguese rule in the inland with reference to the continued existence of the Arab slave trade and began to intervene in the area north of Limpopo.

In 1888 the British colonial politician Cecil Rhodes acquired mining rights from Ndebele King Lobengula . In 1889 Rhodes received a license for the British South Africa Company , with which he - supported by departments of the Cappolizei and hired adventurers - made the Matabele Kingdom and areas north of the Zambezi his own (see also below). He promoted the settlement and the precious metal and mineral processing. Both the Ndebele and the Shona undertook bitter but unsuccessful uprisings against European colonization in 1896–1897.

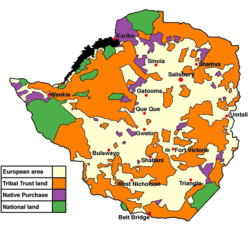

In 1911 Rhodes' territory was divided into Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia ) and Southern Rhodesia , which became a self-governing British settlement colony in 1923 . In 1930 the country was divided into white and black settlement areas, and so African agriculture was displaced into low-yield areas. In 1950 Joshua Nkomo founded the National Democratic Party , which fought for complete independence for the country. In 1953, the two parts of Rhodesia were reunited and connected to Nyasaland, now Malawi , to form the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland under the leadership of Roy Welensky . After the dissolution of the federation in 1963, the whites living in southern Rhodesia, supported by the apartheid government of South Africa , demanded their independence (Rhodesia 1964).

While black African majority governments seized power in neighboring Northern Rhodesia and Nyassaland, a white minority government under Ian Smith unilaterally declared independence on November 11, 1965. Great Britain called the declaration illegal, but did not enforce a violent restoration of the old conditions. The majority of African leaders then went to the Zambian exile or been imprisoned by the white government. When negotiations failed in 1966 and 1968, Great Britain demanded economic sanctions against Rhodesia from the United Nations . The white minority government proclaimed the republic in 1970 . This was not recognized by any country in the world except the Republic of South Africa.

In contrast to South Africa, Rhodesia's census voting rights were not based directly on skin color, but on income and education. Regardless of skin color, anyone who could fill out the registration form and achieved a certain income level was eligible to vote. In practice, this electoral system largely excluded the African population from political participation; only a few thousand Africans could ever be registered, although theoretically a few tens of thousands would have been eligible to vote. Men and women were allowed to vote in the 1930 elections. However, since active and passive voting rights were tied to educational criteria and financial requirements, namely to paying income tax or property, fewer than 2,000 black Africans voted. Between 1953 and 1964 Zimbabwe was in a network with Malawi and Zambia. At that time, the right to vote in Zimbabwe was gradually extended to black women for the first time. Before 1957, only men and European women could vote. From 1957 onwards, married black women were granted limited voting rights and gradually expanded. There was a special voter list for black women, in which they were included under certain conditions (education, wealth). The women were treated in the same way as their husbands; in the case of multiple marriages, however, this privilege only applied to the first woman. Wives had to read and write the English language and be able to prove that they had attended school. To be registered for an election, an individual had to meet one of the following four requirements: an annual income of at least £ 720 or real estate of at least £ 1500; Annual income of £ 3,480 and real estate valued at £ 1,000 plus primary education that met required standards; religious leadership after the person had completed a certain training, was able to demonstrate a certain period of office and only if no other profession was exercised; political leaders (chiefs) according to legal requirements. These complex electoral requirements were included in the 1961 constitution, which allowed blacks 15 seats in parliament. Around 50,000 blacks were able to exercise limited political power at that time.

In 1969 a constitution was presented. This curtailed the role of the black electorate, especially that of women, because half of the seats reserved for blacks were given by a male electoral body. In 1970, a separate electoral register was created for the Africans and 16 members of parliament were assigned to them; their number should increase with the growing tax share of the black majority population. However, the requirements were set so high that a takeover of power by the black majority “for a thousand years” should be ruled out (realistic forecasts assumed that this case could have come about between 2030 and 2070).

Racial segregation prevailed in Rhodesia, but not apartheid in the South African style; the African population was involved in the economy and administration and made up the majority of professional soldiers (officers only from 1977) and the paramilitary police, but conscription was only for whites. It was not until 1978 that the general active and passive right to vote was introduced.

Rhodesia conflict and growing African nationalism (1965–1980)

Unilateral independence and UN sanctions

Immediately after Rhodesia declared independence in 1965, Britain adopted a policy of economic sanctions. It became the spokesman in the UN committees. The UN Security Council gradually took over the positions shaped by British foreign policy and adopted fully binding sanctions measures in May 1968. The United States prevented together with the UK in 1970 at the United Nations to extend the sanctions on South Africa and Portugal . Both states were among the main supporters of Ian Smith's system of government.

This approach, which has been consolidated over the years, contributed significantly to the growing tension in the domestic political situation. The Smith government relied on a tightening of its racially justified supremacy, an immigration policy to strengthen the ethnic group of the European population and the recruitment of well-trained mercenaries in the western states for tasks in the Rhodesian armed forces or paramilitary organizations ( e.g. Rhodesian Special Air Service ). Diverse and long-established connections between military and secret service circles in South Africa and Rhodesia proved helpful. South Africa initially tried, as part of its detente policy, to create a system of government in the neighboring state that was acceptable to it by means of relaxation.

Guerrilla warfare

In 1966 the rebels of ZANU and ZAPU declared a guerrilla war against the “white” power structures. The military activities of the few and inexperienced fighters initially remained low and sporadic. It was only between 1973 and 1974 that the attacks from the Mozambican province of Tete achieved noticeable foreign policy effectiveness, which led, for example, to the South African government's conviction that the fragile Smith regime would be better placed in the sphere of influence of its Africa policy through an alternative, more stable system of power controlled from Pretoria to involve. Meanwhile dissatisfaction with government policy also grew among the white population. In response to the results of the negotiations at the Rhodesia Conference in Geneva, some members of the ruling party resigned from the Rhodesian Front on July 3, 1977 . Shortly afterwards they founded an ultra-right party, the Rhodesian Action Party, with a negative attitude towards previous government policies.

Smith responded by dissolving parliament and holding new elections for 85,000 whites and a very small circle of “black” voters. Ambiguities in the preparations for the election and with regard to future political goals contributed to the unstable domestic political situation. To make this more difficult, there were clear political divergences in public in 1977 among the African nationalist leaders involved, such as Abel Muzorewa , Joshua Nkomo , Robert Mugabe and Josiah Tongogara . The latter led a guerrilla group and had received military training in the People's Republic of China . During this phase the Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere tried to reach an agreement among the nationalists and in August 1978, after a conversation with US President Jimmy Carter, he could count on support for his efforts. But Nyerere also emphasized that the solution for Rhodesia could only be achieved by dismissing Ian Smith by means of violence. Muzorewa tried together with Smith to weaken the liberation movements in Rhodesia. This strengthened the political basis in South Africa for influencing conditions in its neighboring country according to one's own ideas. With extensive arms and fuel deliveries, it preserved the functionality of the military structures of Rhodesia. If necessary, SADF units intervened directly or indirectly in the military conflicts in the neighboring country. By cooperating with the Rhodesian security forces, South Africa tried to destabilize the situation in Mozambique , since MK groups of the ANC had moved into important retreat areas there.

Mugabe turned to Beijing in this situation and publicly commented on the Rhodesian situation during his stay. In doing so, he snubbed other nationalist leaders who, on the other hand, sought support in the Soviet-controlled Eastern Bloc .

Efforts to negotiate, which should lead to a peaceful solution to the Rhodesian conflict and to a power participation of the African people, failed because of the division and information policy of the government of Ian Smith.

From the mid-1970s, the economic situation for the white government began to deteriorate: Mozambique's independence offered the rebels an additional refuge, relations with South Africa cooled noticeably, and the ever-expanding guerrilla war confronted white Rhodesian society with ever greater proportions Charges. More and more men were drafted into the security forces for longer and longer, and attacks on remote farms and on the traffic routes increased. Labor shortages, acts of sabotage, a rising military budget, fuel shortages and expenses for securing settlements and farms all affected the country's economy. The political and military leadership finally came to the realization that the war could no longer be won militarily and that the participation of the black majority in the government was inevitable. Smith therefore started negotiations with moderate, conservatively oriented African leaders who were not involved in the guerrilla war, to resolve the war within the framework of an internal settlement without involving the guerrillas, neighboring African states and western countries ( especially the former colonial power).

Transitional government

After several secret constitutional meetings between Smith, Muzorewa, Sithole and Chirau , which took place from December 1977 to March 1978, Smith signed an agreement on March 3, 1978 with three black leaders under the leadership of Bishop Abel Muzorewa to form a transitional government called the Provisional Executive Council . The Provisional Executive Council was supposed to work towards a speedy resolution of the conflict, which it was too late for in view of the continuing escalating guerrilla war. The Provisional Executive Council finally agreed on a complex mode for the election of a parliament with 100 members, in which 28 seats would in fact be reserved for the whites:

- 72 seats were distributed among the parties according to proportional representation .

- 20 seats were reserved for the voters of the “White Roll”. The “White Roll” was the electoral roll used until the 1974 general election . It was drawn up in accordance with the census suffrage: Only those who met certain requirements in terms of property, assets and formal schooling were entered. Almost all blacks were excluded.

- The remaining 8 seats were given to whites who did not meet the requirements for the "white roll".

According to this mode, the parliament was elected by three partial elections of the three groups of voters mentioned on April 10, April 21 and May 7, 1979. With a high turnout, Muzorewa's party won an absolute majority with 51 out of 100 seats.

At midnight on June 1, 1979, the new constitution came into force, the country was renamed Zimbabwe-Rhodesia , and the new government, with Muzorewa as head of government, began work. Ian Smith, who remained in cabinet as a minister with no portfolio , told the press that he was asleep at the time.

However, the transitional government was unable to meet the high expectations placed on it - the end of the civil war, the lifting of economic sanctions, international recognition - precisely because the necessary actors were not involved in it. Nevertheless, the “internal solution” represented a first step towards internationally recognized independence. As part of the Conference of the Heads of State of the Commonwealth of Nations in Lusaka , the British government invited all parties to a peace conference in London on September 12, 1979 began in Lancaster House . With the mediation of Lord Carrington , representatives of the Patriotic Front and the Zimbabwean-Rhodesian interim government agreed after weeks of negotiations on a ceasefire and elections involving the Patriotic Front. To enable the elections to go smoothly, Southern Rhodesia should be briefly re-declared a British colony and an international police force should monitor the ceasefire and monitor the elections.

In December, the Lancaster House Agreement was signed, the armistice entered into force and the Zimbabwean-Rhodesian Parliament withdrew the unilateral declaration of independence of 1965. The government and parliament dissolved, and Lord Christopher Soames became the last governor of Southern Rhodesia .

Recognized independence

The new elections at the end of February 1980 led to a surprising election victory for Western observers, Robert Mugabe , whose ZANU-PF had its backing mainly from the numerically dominating Shona . Mugabe thus established his enduring career as a key driver in Zimbabwe. Muzorewa suffered a devastating defeat, and his UANC party received only 3 seats out of a possible 100 in the newly elected parliament. This result was a political shock for the government in South Africa. The Citizen in Johannesburg wrote on March 5, 1980 " Mr. Mugabe won a landslide victory that transcends even our worst expectations ." The thus changed balance of power in Southern Rhodesia effectively ended Pretoria's political strategy of a community of states in Southern Africa. But also domestically, this election result meant a new insight for South Africa. It became clear that the collaboration of black puppet politicians with a white government found no support from black voters. The independence ceremony took place on April 18, 1980, but 20 of the 100 seats in parliament were reserved for the white minority for seven years - in addition to the guarantee that land ownership and pension rights would remain intact.

According to Rhodesian data, the War of Independence claimed 20,350 lives (468 white civilians, 1,361 members of the security forces (around half white), 10,450 insurgents and 7,790 black civilians). The rebel groups spoke of over 30,000 dead.

Establishment and reorientation 1980–1990

In October 1981 there were nationwide strikes involving over 1,000 nurses and teachers; 200 of them were arrested or given suspended sentences.

On December 18, 1981, a bomb explosion occurred in the ZANU party headquarters, killing six people and injuring more than 100.

At the beginning of February 1982, the ZANU security forces discovered several arsenals which, according to State Minister Muangagwa, had been set up by the ZAPU. For this reason, on February 17, 1982, Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo, who had been appointed president, and two other ministers were dismissed from the cabinet for plotting a conspiracy. As a result of the government crisis, fierce fighting (so-called Gukurahundi ) broke out between ZAPU supporters (so-called dissidents ) in the Ndebele-speaking part of the country and the ruling ZANU. The government assumed that South Africa was secretly involved in the unrest and acted accordingly.

On March 4, 1982, nine white MPs from the Republican Front (RF) left their faction to cooperate with the government as independents in parliament. After a cabinet reshuffle, two members of the RF were appointed ministers on April 16, 1982.

On April 18, 1982, the capital Salisbury was renamed Harare.

In 1987 the Mugabe government (ZANU) carried out “punitive expeditions” to north and south Matabeleland against the competing ZAPU movement, with numerous civilian victims. Negotiations on a peace treaty then resulted in the merger with the ZAPU to form the ZANU-PF (1988).

Strengthened in this way, the ruling party decided to turn the 1990 elections into a vote on the establishment of a one-party government and anchoring socialism in the constitution. Despite the favorable outcome for them, the project was discontinued for fear of an international flight of capital and instead adopted economic measures and austerity programs supported by the IMF . This turnaround was justified not least by the probably worst drought of the century in southern Africa, which occurred in 1992 and hit Zimbabwe so severely that a national emergency was declared.

Foreign policy 1980–1989

From 1980 the US tried to improve relations with Zimbabwe, which had close ties with the Soviet Union , and between 1981 and 1986 gave aid totaling US $ 350 million. As the leader of the non-aligned movement , Robert Mugabe consistently criticized the United States and also supported a resolution in the United Nations Security Council condemning the US invasion of Grenada , but abstained from condemning the Soviet downing of a South Korean passenger plane. In July 1986, US President Ronald Reagan suspended a US $ 20 million aid program.

On August 8, 1981, more than 100 military advisors from North Korea arrived to build and train an elite force in the armed forces.

The ZAPU supported resistance groups of the South African African National Congress (ANC) and the Umkhonto we Sizwe . South Africa responded with a bombing raid on Thornhill Air Force Base in Harare on July 25, 1982, destroying ten aircraft and seriously damaging five.

Dictatorship and economic crisis from 1990 to the fall of Mugabe

In the early 1990s, President Mugabe began a campaign against homosexuality , which he portrays as "unnatural" and "un-African". Homosexuals - who for Mugabe are "inferior to pigs" - have since been punished with ten years in prison. In 2006, acts such as kissing and holding hands between gays were criminalized.

Despite the majority government, which increasingly took on the form of a personal dictatorship, the whites - less than 1% of the population - had 70% of the arable land in their hands for commercial use. In 1999 the government began proclaiming the distribution of returned land as a vital program. The “ fast-track land reform ” since 2000 developed from a program of land redistribution from white farmers to landless black farmers into a violent campaign against the opposition, some of which were racist. According to ARD reports, occupied farms were taken over by relatives and friends of Mugabe's. Along with periods of drought, the campaign contributed to the ongoing economic crisis and food shortages in the country. The whites, who produced most of the gross national product as well as the food, were put under increasing psychological and physical pressure by Mugabe.

The most important opposition party since 1999 has been the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), led by Morgan Tsvangirai until 2018 , and from 2005 Movement for Democratic Change - Tsvangirai (MDC-T), which was able to steadily broaden its base, mainly due to the increasing dissatisfaction with the government .

Zimbabwe has been suspended from the Commonwealth for violations of human rights and postponing the 2002 elections and election fraud .

As a result of expropriations, corrupt currency management and the high rate of agricultural exports that have been maintained, the social situation deteriorated, especially in the countryside. The economy suffered, not least among them that Zimbabwe is an HIV / AIDS - a pandemic raged; however, the rate of 15 to 49-year-olds infected with HIV fell to 13.5% by 2016.

In 2001 young people were called up to the National Youth Service in camps for the first time . There they are trained politically and militarily in accordance with the ZANU-PF. According to press reports, political opponents such as the MDC are being hyped up as enemies in the camps and young green bombers are being trained in torture techniques. Female inmates must fear sexual abuse. In the long term, every young person should go through this service.

Around 2002, Western trading partners and donors increasingly withdrew from Zimbabwe. As a result, China's influence on the country increased.

The independent daily Daily News , which had been bombed several times, was banned in 2003. In December 2003 the country left the Commonwealth.

The " Operation Murambatsvina ", during which slum settlements were crushed in 2005, was criticized internationally. In the same year Mugabe's ZANU-PF won the general election; he was again accused of voting fraud. As of 2006, the Zimbabwe dollar was devalued due to hyperinflation . In 2007, opposition leader Tsvangirai was severely ill-treated by police officers.

In March 2008 there was a presidential election . In the first round, Tsvangirai received 47.9% more votes than Mugabe, but he was harassed and withdrew before the second round. After Mugabe had clearly won the election in the second round, he became president of a unity government in February 2009 with Tsvangirai as prime minister. From August 2008 to June 2009, the country experienced a cholera epidemic that hit all provinces and killed over 4,000 people. In November 2008, hyperinflation peaked with a calculated annual price increase of 79.6 billion percent.

The Zimbabwe dollar was effectively abolished in 2009 and replaced by foreign currencies; In 2015 it was officially withdrawn from circulation. In 2010 the Daily News was re-admitted. In the 2013 presidential election, which was held for the first time together with the parliamentary election, Mugabe again clearly won; in parliament his ZANU-PF received a two-thirds majority . At the same time, a new constitution was adopted that limits the president's term of office to two five-year terms.

Military coup and presidency of Emmerson Mnangagwas

On November 15, 2017, the military effectively took power. Mugabe had previously sacked his Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa , who had received military support. On November 19, Mugabe was deposed as chairman of ZANU-PF; Mugabe resigned as president on November 21 after parliament launched impeachment proceedings. Three days later, Mnangagwa was sworn in as president.

On July 30, 2018, presidential and parliamentary elections were held, from which Mnangagwa and his party ZANU-PF emerged victorious. The opposition called for protests and questioned the validity of the election.

In January 2019, riots erupted under Mnangagwa's rule, killing up to 17 people after the government more than doubled gasoline prices. The United Kingdom then refused to support a re-entry into the Commonwealth.

See also

Single receipts

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 272.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 339.

- ↑ a b c d e f June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 7.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 429.

- ↑ a b c - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 13, 2018 .

- ^ Peter Godwin , Ian Hancock : 'Rhodesians Never Die'. The Impact of War and Political Change on White Rhodesia, c.1970-1980 Baobab Books, Harare 1995, ISBN 0-908311-82-6 , p. 152.

- ^ Simplified presentation of the Rhodesian suffrage in: Dolf Sternberger, Bernhard Vogel, Dieter Nohlen, Klaus Landfried (eds.): The election of parliaments and other state organs. Volume II: Africa: Political Organization and Representation in Africa. De Gruyter, 1978, ISBN 3-11-004518-4 , pp. 1627-1690.

- ↑ Martin Pabst: Zimbabwe. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-39878-2 , p. 63.

- ↑ Caroline Daley, Melanie Nolan (Eds.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York University Press New York 1994, p. 352.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 429.

- ↑ Ruth Weiss , William Minter, Hans Detlef Laß: Rhodesia's future is called Zimbabwe. Between colonialism and independence . ISSA - Bonn / Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-921614-35-X , pp. 15, 28, 67.

- ↑ Weiss, Minter, Laß, 1977, pp. 18-19, 20.

- ^ Ronald Meinardus: The Africa policy of the Republic of South Africa . ISSA , Bonn 1981, p. 139.

- ↑ a b Weiss, Minter, Laß, 1977, pp. 69, 84-85.

- ↑ Meinardus, 1981, p. 430.

- ↑ Weiss, Minter, Laß, 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ Meinardus, 1981, p. 121.

- ^ Proportional suffrage in Rhodesia . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of June 2, 1978, p. 4.

- ↑ BBC On this day report: June 1, 1979 .

- ^ Ronald Meinardus: The Africa policy of the Republic of South Africa . Bonn 1981, ISBN 3-92164-50-3 , pp. 145-148.

- ↑ Peter Godwin , Ian Hancock : "Rhodesians Never Die". The Impact of War and Political Change on White Rhodesia, c. 1970-1980 . Baobab Books, Harare 1995, ISBN 0-908311-82-6 , pp. 208 f, 374.

- ↑ Fischer World Almanac. 1983, ISSN 0430-5973

- ↑ Dan Smith: The Fisherman's Atlas Wars and Conflicts. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-596-13637-7 .

- ^ K. O'Brien: Special Forces for Counter Revolutionary Warfare: the South African Case. ISSN 0959-2318 .

- ^ Zimbabwe gay rights face dim future. bbc.co.uk of November 17, 1999 (English), accessed November 15, 2017

- ↑ Zimbabwe criminalizes holding hands between gays. dbna.de from July 2006, accessed on November 15, 2017

- ^ Zimbabwe suspended by Commonwealth. sahistory.org.za, accessed November 14, 2017

- ↑ United Nations HIV statistics for Zimbabwe , accessed on November 14, 2017

- ^ Andrew Meldrum: Living in fear of Mugabe's green bombers. The Guardian, February 19, 2003, accessed November 14, 2017

- ↑ Sapa / dpa: MPs horrified at Zim youth camps - report. iol.co.za, May 24, 2007, accessed November 14, 2017

- ↑ Simon Tisdall: Zimbabwe: was Mugabe's fall a result of China flexing its muscle? The Guardian, November 17, 2017, accessed November 17, 2017

- ↑ a b c d e Zimbabwe profile - Timeline bbc.com from September 21, 2017 (English), accessed on November 13, 2017

- ↑ Cholera in Zimbabwe - update 4th WHO from June 9, 2009 (English), accessed on November 14, 2017

- ↑ Steve H. Hanke, Alex KF Kwok: On the measurement of Zimbabwe's hyperinflation. In: Cato Journal 2009/5 (PDF), accessed on November 14, 2017

- ↑ Mugabe is under house arrest. 20min.ch from November 15, 2017, accessed on November 15, 2017

- ↑ Mnangagwa sworn in as Zimbabwe's new head of state. spiegel.de from November 24, 2017, accessed on November 24, 2017

- ↑ Zimbabwe enters a new era, but struggles to escape its past. BBC News, August 4, 2018, accessed August 4, 2018 .

- ^ Ray Ndlovu: SADC backs Mnangagwa despite Zimbabwe crisis, calls for end to sanctions. timeslive.co.za on February 12, 2019, accessed on February 14, 2019

literature

- David N. Beach: The Shona and Zimbabwe 900-1850. Heinemann, London 1980, ISBN 0-435-94505-X . (also: Mambo Press, Gwelo 1980)

- Schoresch Davoodi, Adama Sow: Democracy and Peace in Zimbabwe. ( Memento of March 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: EPU Research Papers. Issue 12/08, Stadtschlaining 2008.

- Farai Maguwu: Land Reform, Famine and Environmental Degradation in Zimbabwe. In: EPU Research Papers. Issue 06/07, Stadtschlaining 2007.

- items

- Willy Lützenkirchen, photos: Georg Fischer: Zimbabwe: Peace that came like a miracle. In: Geo-Magazin. Hamburg 1980, 6, pp. 84-110. Historically informative experience report. ISSN 0342-8311

Web links

- The history of the Shona Tribe of Zimbabwe (English)

- Africanet: Zimbabwe History (English)

- Abstract in the Encyclopaedia Britannica: Zimbabwe: History (English)

- Issues in African History ( Memento of 30 December 2013, Internet Archive ) on the website of the University of Iowa (English)

- Mapungubwe: SA's lost city of gold The fall of Mapungubwe coincided with the rise of ancient Zimbabwe

- A Brief History of Botswana The previous culture also included the east of what is now Botswana

- Peter S. Garlake: Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe (PDF; 3.9 MB, English)

- Pre-colonial Fortified Settlements in Northern Zimbabwe, 1550–1750 AD ( Memento from May 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Cefala (Sofala) and the Gulf States in its hinterland from the Voyages Fameux by Vincent Leblanc 1648, translation from 1660 (English)