Greater Zimbabwe

| Great Zimbabwe National Monument | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Inside the great enclosure |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, iii, vi |

| Reference No .: | 364 |

| UNESCO region : | Africa |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1986 (session 10) |

Greater Zimbabwe (also Old Zimbabwe , English Great Zimbabwe ) is a ruined city 39 kilometers from Masvingo in the Masvingo Province in Zimbabwe . The name Zimbabwe means 'great stone houses' or 'honored houses' depending on the dialect. The settlement on the plateau of the same name was the capital of the fallen Munhumutapa Empire (also Monomotapa Empire ), which in addition to present-day Zimbabwe also included parts of Mozambique . Greater Zimbabwe had up to 18,000 inhabitants in its heyday from the 11th to the middle of the 15th century, was used by the Zimbabwean monarchs as a royal palace and was the center of political power. The wealth of the metropolis was based on cattle breeding , gold mining and long-distance trade . The Zimbabwe birds made of soapstone are evidence of the spiritual center . The facility is the largest pre-colonial stone structure in sub- Saharan Africa and one of the oldest.

The city was already abandoned and decaying when Europeans first noticed it in the 16th century. For a long time it was mistakenly interpreted as the home of the Queen of Sheba . The results of archaeological research refute this thesis, however; The late Iron Age is assumed to be the origin of the complex , which in this region corresponds to the 11th century.

Great Zimbabwe is on since 1986 UNESCO list of World Heritage .

geography

Location of Greater Zimbabwe in the Masvingo Province in Zimbabwe . |

location

Greater Zimbabwe is 240 kilometers south of the capital Harare and about 25 kilometers south-southeast of Masvingo, the former Fort Victoria, in the Masvingo Province in the southern half of Zimbabwe. The ruins are at an altitude of 1140 m . Immediately to the north, about two kilometers away, begins the Mutirikwi Recreational Park with Lake Kyle and Lake Mutirikwi . This reservoir covers about 90 km² and has been dammed since 1960 when the Kyle Dam was built in the Mutirikwi River , a tributary of the Runde .

The location on this plateau offered the city a natural protection against sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis) . This disease, spread by the tsetse fly , can kill humans and cattle, but tsetse flies are only found in lower-lying areas.

To the southwest of the ruins is the Morgenster Mission , a mission station and hospital built in 1894 by John T. Helm on behalf of the Dutch Reformed Church . The road to Masvingo leads to the north and the small town of Dorogoru to the east .

structure

The site covers a fenced area of 722 hectares and is divided into four parts: The so-called mountain ruins are located on the hill . in the valley south of it, the fences , east of it, the museum Shonadorf and west perimeters modern infrastructure with hotel, campground, administrative buildings and access roads.

A relatively wide valley opens to the south of the mountain ruins, in which there are fences, of which the large fence is the southernmost structure. In the west - from north to south - are the Outspan ruins , the camp ruins and the hill ruins . The other, smaller ruins were named primarily after their respective explorers: Immediately north of the Great Enclosure are ruins no. 1 , the Posselt ruins , Renders ruins and Mauch ruins . To the east of it are the Philips ruins , the Maund ruins and the Ostruine .

geology

The area on which the ruins of Great Zimbabwe are located is about 110 kilometers east of the Great Dyke , where coveted precious metals , especially gold , were mined. The subsoil of Greater Zimbabwe itself consists predominantly of granite with massive gneiss veins that were formed in the early Precambrian through contact metamorphosis . Geological investigations have shown that the granite blocks used to build the walls are mainly based on biotite . The composition consists of 35% quartz , 58% feldspar ( microcline 28%, plagioclase 30%), 4% biotite, 3% muscovite and less than 1% iron ore . Diorite was used as the harder stone for processing the granite for the structures .

climate

The place is located in a subtropical to tropical climate zone with humid, sometimes humid and hot summers and winter dry season. The average annual temperature in Greater Zimbabwe is between 20.8 and 26.1 ° C. The warmest months are October and November with an average of 29.2 and 28.7 ° C, the coldest June and July with 5.8 and 5.4 ° C on the minimum average. The temperature almost never falls below freezing point. Most of the precipitation is recorded in December with an average of 140 millimeters, the lowest in June and July with an average of 3 and 6 millimeters. Because of the summer monsoon , precipitation falls particularly in the period from mid-November to the end of January; the annual average is 614 millimeters. According to Innocent Pikirayi, lecturer in history and archeology at the University of Zimbabwe and expert on the excavation site, the rainfall for the area around the ruins is said to be higher, namely 800 to 1000 millimeters per year, which would mean that agriculture was more productive.

vegetation

The vegetation in Greater Zimbabwe, especially the Mobola plum or Muhacha ( Parinari curatellifolia ), a golden plum plant , is ascribed a mythical meaning. Exotic plants brought from the now dominate the city are the Jacaranda ( Jacaranda mimosifolia ), the eucalyptus and the lantana ( Lantana camara ). Over time, the ruins were made up of many specimens of the red milkwood ( Mimusops zeyheri , from the genus of the sapote family ) and overgrown by a shrubby nettle ( Girardinia condensata ).

history

Surname

There are two theories about the origin of the word "Zimbabwe": The first is that the word is derived from Dzimba-dza-mabwe , translated from the Karanga dialect of the Shona as "great stone house" ( dz imba = the houses, ma bwe = the stone) or large stone house / stone palace (the prefix z- marks a form of enlargement like the Italian suffix -one ). The Karanga-speaking Shona live all around Great Zimbabwe; presumably they already inhabited the region when the city was built. The second theory assumes that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of dzimba-hwe , which means "honored houses" in the Zezuru dialect of Shona, a term used for the tombs and houses of the chiefs. The city was named after the state of Zimbabwe (also Zimbabwe, formerly Southern Rhodesia ).

The addition "Groß" (or English "Great") is used to differentiate between around 150 smaller ruins, called "Zimbabwe" , which are distributed over the entire country of Zimbabwe. There are also around 100 Zimbabwe in Botswana , while the number of Zimbabwe in Mozambique cannot yet be estimated.

Iron Age history

The area around Greater Zimbabwe was settled between 300 and 650 AD. Rock paintings in Gokomere, about eight kilometers from Masvingo, bear witness to this . The Gokomere / Ziwa tradition with its characteristic ceramics and the use of copper is archaeologically assigned to the Iron Age . The Ziwakultur did not build any stone buildings.

The first rural settlements in Mapungubwe on Limpopo date back to around the year 900. The kingdom there existed between 1030 and 1290; with its decline due to changed climatic conditions, the rise of Greater Zimbabwe began. On the plateau of Greater Zimbabwe, hunters and gatherers, Iron Age agriculture and societies based on the division of labor seem to have collided directly. Several states emerged partly one after the other, partly in parallel. Greater Zimbabwe was the first center of the Mutapa empire, whose power extended to the coast and also went north and south beyond what is now Zimbabwe. Khami , a similarly large complex of walls seven kilometers west of Bulawayo , was initially built in parallel and later became the center of the Torwa Empire.

The Kingdom of Munhumutapa

Greater Zimbabwe is one of the oldest stone structures south of the Sahara . Work began in the 11th century and continued through the 15th century. There is strong evidence, but no clear evidence, that the builders and residents of the city were ancestors of today's Shona , the Bantu people who make up about eighty percent of the population of today's Republic of Zimbabwe. The ceramics found are very similar to today's. But since this culture did not develop a script, the final proof is lacking. In the heyday, 20,000 people are said to have lived on the area. Trade connections with Arab coastal cities are archaeologically documented by coin finds. In addition to numerous objects from the heyday, ceramics were found in the area, which are 600 years older than the buildings. The country's gold wealth was the main reason for the trading activities of Arab and Persian traders on the southern tip of Africa and for the founding of cities by the Swahili in Mozambique . Greater Zimbabwe was abandoned around 1450, probably because the high population concentration had drained the country. The Mutapa state shifted its center north and lost its supremacy to the Torwa state. The capital Khami became the new center for about 200 years .

Expeditions and archaeological exploration

Portuguese expeditions and their reception

As the first Europeans, the Portuguese founded a fort near Sofala at the beginning of the 16th century and tried to get their hands on the South African gold trade. So they were looking for Mwene Mutapa , head of the Karanga kingdom. In a letter from Diego de Alçacova to the Portuguese king from 1506, it is said that in Zunbahny , the capital of Mwene Mutapa, "the king's houses ... made of stone and clay, are very large and on one level" . In 1511, the Portuguese explorer António Fernandes was the first European to visit the site. He reported that "Embiere ... a fortress of the King of Menomotapa ... now made of stone ... without mortar " was. They also carried the legend to Europe that the city was the home of the Queen of Sheba . In 1531 Vicente Pegado , captain of the Portuguese garrison in Sofala, described Greater Zimbabwe as follows: “In the middle of the gold mines on the inland plains between the Limpopo and Zambesi rivers there is a fortress that was built of astonishingly large stones and completely without mortar ... This one The structure is almost entirely enclosed by hills on which similar stone structures stand without mortar. One of these structures is a tower over 22 meters high. The natives of the country call these buildings Symbaoe , which means courtyard in their language. ” João de Barros published the report in 1552 in his work Décadas da Ásia . The information was based primarily on descriptions by Swahili traders in Sofala.

The other mention of stone buildings in this early period can be found in the work Ethiopia Oriental by João dos Santos , published in 1609 , who worked as a missionary in the country of Mwene Mutapa between 1586 and 1595 . Its details refer to stone buildings at the other end of the plain, opposite Great Zimbabwe, on the Fura Mountain (today Mount Darwin ) in Mashonaland :

- “On the top of this mountain there are still some fragments of old walls and ancient ruins made of stone and mortar. ... The natives ... assure you: It was passed down to them by their ancestors that these houses were once a trading post for the Queen of Sheba. Large amounts of gold were brought from here, which were transported by ship on the Cuamas rivers to the Indian Ocean ... According to others, the ruins come from a settlement of King Solomon . ... Although I cannot express myself bindingly, I claim: The Fura or Afura mountain could be the "Land of Ophir", from where gold was brought to Jerusalem . This would give some credibility to the assertion that the buildings in question were King Solomon's trading post. "

Shortly after dos Santos published his report, Diogo de Couto , the successor of João de Barros, added to De Asia that “it is believed that ... the Queen of Sheba ... had gold mined in these places ... the great stone structures ... are called Simbaoe by the Kaffirs , and they are strong fortifications. ”Although de Barros and dos Santos recognized that they were embarking on questionable speculations, the performances they presented to the public caught the imagination of their recipients to such an extent that their description made two hundred It was repeated for years by the best geographers in Europe and its "exotic accessories grew to the same extent that speculation that still had something to do with conceptual thinking was transformed into an unquestionably accepted dogma." Such repetitions can be found in the works the Italians Sanuto (1588) and Pigafetta (1591), the Englishmen Samuel Purchas (1614), John Speed (1627), John Ogilby (1670) , Peter Heylin (1656) and Olfert Dapper (1668) as well as the French Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1727) and Charles Guillain .

Karl Mauch's expedition (1871)

After Adam Renders (1822 – after 1871) rediscovered the ruins in 1868 while hunting and claimed that “they could never have been built by blacks”, he showed them to Karl Mauch (1837–1875) on his fourth trip to southern Africa in 1871 . This equated them with the biblical gold country Ophir , 2000 years earlier than today's radiocarbon dating. Then he passed the upper course of the Zambezi , where he found a gold field (Kaiser-Wilhelms-Feld). Mauch, who was ill with malaria, returned to Germany in 1872. He later questioned his own Ophir Zimbabwe theory. The first publication by Alexander Merensky about the Zimbabwe ruins appeared in Petermanns Mitteilungen in Berlin in 1870 . In it he had summarized research reports.

James Theodore Bent's Expedition (1891)

When Cecil Rhodes conquered Mashonaland with the help of the British South Africa Company in September 1890 , he told the local Bantu chiefs that he had come to see "the ancient temples that once belonged to the whites." With William G. Neal, the head of the Ancient Ruins Company , who carried out robbery excavations on this and other Iron Age sites in Zimbabwe and destroyed important findings, he commissioned James Theodore Bent (1852-1897) to investigate the ruins in 1891 .

Bent's archaeological experience lay in the fact that he had traveled to the countries of the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf in search of the origin of the Phoenicians . As an archivist , he seems to have a tendency towards antiquity, but no archaeological training - and even less practical experience. In June 1891, Bent began digging around the conical tower in the elliptical structure and was very disappointed with the results. He later claimed the ruins were built by either Phoenicians or Arabs. But his reports made the ruins known to a wider English readership.

Much of the archaeological stratigraphy was destroyed during the excavation by Bent's team , making it more difficult for later archaeologists to determine the age of Greater Zimbabwe. In the end, Bent's team suggested that a “bastard” race of male white immigrants and Africans had constructed the structures. During Bent's research, the ruins were surveyed by mining engineer Robert Swan. Based on his plans, Swan developed his own theories, which assumed precise designs based on the number pi for the larger sections of ruins . On the basis of Swan's observations - and his assertion that altars that had now disappeared and were oriented towards the solstices had now stood in the centers of the elliptical arches - the geologist Henry Schlichter later attempted to calculate the absolute age of the due to their natural variability. He came to 1000 BC. However, since Swan's measurements were incorrect and taken at randomly selected points, this theoretical structure proved untenable.

Peter Garlake pointed out that in 1892 the British Army Officer, Major Sir John Willoughby , "gutted" three ruins in the valley "regardless of loss", destroying the stratigraphic layers within the north-west entrance to the Great Enclosure.

Carl Peters' expedition (1899)

Carl Peters (1856–1918) led a research trip to the Zambezi in 1899. He wanted to prove that the biblical gold country Ophir had been in Southeast Africa. Since, in the later judgment of the historian Joachim Zeller, he represented "National Socialist positions, a rigid master's position and a racist Social Darwinism", he could not imagine that the ruins of Greater Zimbabwe could be of African origin. He was therefore looking for master builders from the Middle East, with the Phoenicians playing a central role. Peters also wanted to win shareholders for his corporation, which bought land in Portuguese Mozambique to dig for gold there. Peters enriched his Ophir theory with violent defamations against black Africans and demanded the introduction of general forced labor in the colonies.

Richard Nicklin Hall's dig (1902–1904)

The discovery of several gold finds in the Dhlo Dhlo ruins in the 1890s led to the establishment of Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd. , who systematically searched 50 ruins in Zimbabwe for gold finds, but exempted the ruins of Greater Zimbabwe at the express request of Cecil Rhodes. The excavations yielded only 178 ounces of gold jewelry. The company was disappointed with the other finds. The results of the campaign were compiled in a book by local journalist Richard Nicklin Hall . After several financial difficulties, Hall was appointed curator of Zimbabwe in 1902, with the task of protecting Greater Zimbabwe - due to new legislation. Due to a double extension, Hall held this position for almost two years instead of the originally planned six months. His instructions consisted of “not carrying out any scientific investigations”, but to devote himself solely to “maintaining the building”. After Garlake, Hall didn't care what the purpose of his employment was. Instead, he had undocumented excavations carried out in the great enclosure, the mountain ruins and a large part of the other valley ruins. Not only were the trees, aerial roots and undergrowth as well as the spoil heaps of the Bent and Willoughby excavations removed, but also 0.9–1.5 meters, in places more than three meters of stratified archaeological material. His justification for what he himself called "modern and contemporary work of conservation" was that he was only removing the "dirt and trash of the Kaffir people" with the intention of exposing the remains of the "ancient" builders. After the criticism became louder, especially in scientific circles, the London office of the British South Africa Company finally dissolved the contract and dismissed Hall in May 1904.

The excavation by David Randall-MacIver (1905/1906)

The first scientific archaeological dig on the site was carried out in 1905/1906 by David Randall-MacIver (1873-1945), a student and employee of Flinders Petries . In the short time he had at his disposal, MacIver first dug in the ruins of Injanga , Umtali , Dhlo Dhlo and Khami and then with that experience in Greater Zimbabwe. He first described the existence of found objects in "medieval Rhodesia" that can be assigned to the Bantu . The lack of any artifacts of non-African origin led Randall-MacIver to suspect that the structures were carried out by native Africans. This was the first time he set himself apart from earlier scholars who wanted to attribute the buildings exclusively to Arab or Phoenician traders.

The Caton-Thompson Dig (1929)

Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888–1985) examined the "Ruins of Zimbabwe" in 1929 on behalf of the British Association for the Advancement of Science . During this excavation, Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), a British archaeologist, gained her first archaeological experience; she later taught at University College London. From the start, Caton-Thompson limited himself to narrowly defined basic questions about “who?” And “why?” And tried to find datable imported goods in stratigraphic contexts. To achieve these goals, she selected a structure that had been least damaged in previous excavations and had the architectural features of an original structure suggested by Hall , and so whatever she found could only be associated with the original builders. In terms of method, it was the first and only regular area excavation . Their choice fell on the so-called Maund Ruins, seen from the large enclosure at the end of the valley on the other side. She published the material obtained in seven working weeks with all find lists and detailed descriptions of all finds as well as photos of most of the objects.

In order to show that their results could be applied to all structures in Greater Zimbabwe, Caton-Thompson had six search trenches dug outside the great enclosure and a tunnel built under the conical tower. After their excavations, "not a single point remained that was incompatible with the statement that the Bantu people were the builders and that the structure was from the Middle Ages." The archaeologist Graham Connah and many historians believe that the city had to be given up at the end of the Middle Ages because the permanent over-settlement had led to an ecological catastrophe.

The Dig by Roger Summers, Keith Robinson and Anthony Whitty (1958)

In 1958 a large research program was started by Roger Summers , Keith Robinson and Anthony Whitty . The aim was not to raise the question of the builder again, but to clarify the chronology of the ceramics and the archaeological finds. The goal was: "To set up a ceramic sequence in Zimbabwe". In 1967 the chronology of ceramics was discussed again.

Radiocarbon Dating (1950s and 1996)

In 1950 the first radiocarbon dating was attempted with material from Greater Zimbabwe. These were two piles made of the wood of the Tamboti (Spirostachys africana) discovered in the Great Enclosure in the same year , which supported a drainage ditch through the inner wall of the Parallels Passage, one of the oldest walls in the building. The samples provided the following results: "590 AD ± 120 years (C-613) and 700 AD ± 90 years (C-917) or 710 AD ± 80 years (GL-19)" , the data has not yet been calibrated . Since the trees of the Tamboti can live up to 500 years old, this increases the margin of error in C-14 dating by this time span. It must also be taken into account whether the wood in the finding was possibly used for the second or more time. Ultimately, the data only say that the walls were erected at an unknown point in time after the 5th century AD. The next samples were dated 1952 and resulted in “AD 535 ± 160 years, AD 606 ± 16 years”. It was the same type of wood as the stakes discovered in 1950 and the data was also not calibrated. Further dates were made on material from the excavation of 1958 and resulted in "AD 1100 ± 40, AD 1260 ± 45, AD 1280 ± 45". The most recent dates were made in 1996 in Uppsala on samples of Mopane (Colophospermum mopane) from the wall of the Great Enclosure and resulted in: "1115 ± 73".

architecture

General description of the ruins

The remaining ruins of the city cover an area of seven square kilometers and are divided into three areas: the Hill Complex, which is 27 meters higher, also known as the mountain fortress or Acropolis, the Valley Complex and the elliptical enclosure, the so-called Great Enclosure (also known as the temple ). The walls of Greater Zimbabwe are made of granite blocks and without mortar. The great wall has a base of five meters, a height of nine meters and a total length of 244 meters. The dry stone walls even lack corner connections. And - despite the name - they never had roofs. They were stone fences. In the courtyards enclosed in this way, there were huts and houses made of clay and wood. Standing next to the four-meter-wide staircase to the Acropolis carved into the rock, monoliths could have served astronomical purposes.

Mountain ruins

In the 19th century, the mountain ruins were repeatedly given the ambiguous name "Acropolis" by visitors. At first, only the hill enclosure seems to have borne the name dzimbahwe . The hill extends 80 meters above the so-called valley , on the south side it is formed from a 30 meter high and 100 meter long cliff. The steepest and shortest route to the top is Cliff Ascent . On the high plateau in the west is the eight meter high and five meter thick wall of the western enclosure. Every two meters there were towers with stone pillars on the top of the wall. The only two columns and the four towers that exist today were reconstructed in 1916. The wall itself is original, but part of the outside had to be reconstructed due to damage; the reconstruction is easy to see.

The original entrance to the western enclosure is close to the edge of the steep rock step and is now walled up for safety reasons. The current entrance is part of the wall reconstruction from 1916. The western enclosure, the main area of life on the mountain ruins, was continuously inhabited for 300 years. Remnants of the former huts covered the inside of the enclosure up to eight meters deep. During safety work in 1915, a large part of it was thrown down the cliff. Nevertheless, the original inspection horizons can still be seen in many areas. With the help of inner walls, a similar “parallel passage” seems to have been intended as in the great enclosure in the valley. The southern wall stands directly on the edge of the rock and was decorated with columns. The north and east walls are formed by protruding rocks, over which the wall sections only had to be built by hand in places, because the builders seem to have sought to incorporate nature into their construction. In the north-eastern corner of the mountain plateau, the so-called balcony is about ten meters above the fence. Until the end of the 19th century, there were various granite and soapstone columns in this area, the largest of which was four meters high. One of the Zimbabwe birds was recovered from the rubble in this balcony.

Large enclosure with parallel passage and conical tower

The Great Enclosure was called Imba Huru (Great House) by the locals in the 19th century . The current entrance through the Great Wall is a 1914 reconstruction that was placed in an inaccurate location. The wall is 255 meters long and the weight of the approximately one million stones used was given as 15,000 tons. While the north-western part consists of relatively little ornate stones, the north-eastern part is masterfully made with a height of eleven meters and a thickness of four meters at the top and up to six meters at the base. The wall in the northwestern area is of the poorest quality, and it is only half as high and half as thick as on the other sections. Particularly hard diorite was used to work the stones . The interior of the large enclosure consists of several parts, initially enclosure number 1, the central area, the original outer wall, the conical tower and the narrow tower, as well as the Dakha platforms. Enclosure No. 1, a simple circular wall and the earliest building in the Great Enclosure, is located directly north of the central area. Inside were once a household's huts.

The so-called Parallel Passage connects to enclosure No. 15 in the north. It is formed from the current outer wall of the Great Enclosure and the original outer wall, which was built shortly after Enclosure No. 1. The inner wall is about a century older than the outer one. Archaeologist and former curator of the complex, Peter Garlake, suggested it was about the privacy of the royal family who lived behind the original wall. Privileged guests, who were allowed into the enclosure around the conical tower, could thus be admitted into the great enclosure and yet remained outside the royal living area. The passage is over 70 meters long and only 0.8 meters wide almost everywhere. Between the passage and the tower enclosure there are a number of platforms at different heights. Until 1891, all entrances to the tower enclosure were blocked with well-worked stones.

The conical stone tower is still ten meters high today. Its diameter is five meters at the base and about two meters at the top. Originally there was a three-line ornament on the upper edge, which consisted of stones rotated by 45 ° and thus formed a series of triangles in a zigzag pattern . For a long time it was assumed that there was a secret treasury inside the tower. In 1929 the tower was partially tunnelled by archaeologists, and it turned out that it was built massive and directly on the ground. The original structure and the original appearance of the spire is unknown. (Tower structures of unexplored function were also built in Oman and Nuraghe / Sardinia , for example .)

Enclosures in the valley

In addition to the large enclosure, there are a number of small enclosures: the Outspan ruins, the warehouse ruins, the hill ruins, the ruin No. 1, the Posselt ruin, the render ruin, the Mauch ruin, the Philips ruin , the Maund Ruin and the Ostruine.

Finds

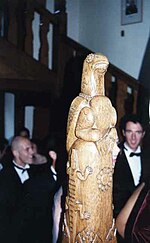

Birds made of stone

Six of the eight stone sculptures were found in the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins, which the population apparently regarded as a sacred place. These Zimbabwe birds are about 0.4 meter high stone figures that were placed on top of pillars and thus reached a height of one meter. Seven of the stone birds are completely preserved. Soft soapstone was used as the material . What is striking about the birds is how unrealistic they are, such as how thick their legs are or how misshapen their bodies.

Some of the birds were returned to Zimbabwe in 2003 after having been in Germany for almost 100 years. Today the birds are a national symbol that can also be found in the country's coat of arms and flag .

The first bird was removed from the Philips ruins by Richard Hall in 1903. The figure is 28 centimeters high and measures 1.64 meters with a foot. It is 23 inches deep and 6 inches thick. It is the most famous of the eight birds because it became the model for the representation on the flag and the coat of arms of Zimbabwe.

The second bird is one of the earliest artefacts removed from the ruins, taken by Willi Posselt from the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins in 1889 and probably sold to Cecil Rhodes. Since the bird was too big, Posselt separated it from the column. The bird is 32 centimeters high with bent legs and 12 centimeters wide at the thickest point. The bird is decorated with a diamond pattern ribbon around its neck.

The third, comparatively roughly shaped bird was removed by Bent from the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins. The figure is 43 centimeters high and 22 centimeters deep. The beak broke off, but it appears that it was the furthest into the sky of all eight figures. The bird stands on a suggested wooden ring (like bird 7).

The fourth bird was also removed from the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins by Bent. It measures 1.75 meters with the support column, whereby the bird is only 34 centimeters high. At the thickest point it is 10 centimeters wide. The eyes are marked by small humps. The tail is clearly spotted.

The fifth bird also comes from the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins and was removed by Bent in 1891. The bird is 1.73 meters high with the column, the figure alone is 33 centimeters high and 9 centimeters wide. The beak is also broken off, the eyes are knobby, the wings are suggested, but smooth. Diamond patterns are indicated on the back. The tail is also clearly spotted.

Bent also removed the sixth bird from the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins. It is 1.53 meters high with the support column. The bird figure itself is 33 centimeters high and 10 centimeters wide. It has similar diamond patterns on its back as Birds 2 and 5.

Only the lower 20 centimeters of the seventh bird have survived. It could have been the smallest of the eight figures and, like bird 3, stands on a suggested wooden ring. It stood in the eastern enclosure of the mountain ruins and was removed by Bent. The tail is decorated with a herringbone pattern.

The broken specimen of the eighth bird was removed from the mountain ruins by Richard Hall in 1902. He is said to have stood on the so-called balcony, from which the western enclosure of the mountain ruins can be seen. Hall found only the upper part of the figure, sold it to Cecil Rhodes, who already owned the lower part. In 1906 the figure came to the Völkerkundemuseum in Berlin through the missionary Axenfeld .

The royal treasure

In the enclosure no.12 in the so-called Renders ruins north of the Great Enclosure, a collection of objects was found in 1902 without observation or documentation of the findings or stratigraphy , which are addressed as royal treasure . About 100 kilograms of iron chopping with traditional designs, but also narrow iron chopping or adzes ( Dechsel ) axes and chisel . Furthermore, an iron gong with narrow iron striking devices, two large spearheads and over 20 kilograms of twisted wire. There were also copper and bronze wires in the find, some of which had already been made into jewelry. Another important find were tens of thousands of small glass beads , probably from India , as well as Chinese celadon- coated ceramics from the 13th century.

Other finds

Only a few finds from the early excavations can be seen in the museum on site. This includes four bronze spears with separate blades, which seem very impractical and were probably intended as a gift. Gongs and the associated batons have also been preserved, but also iron tongs, drawing boards and casting molds that were used by the metalworkers in the great enclosure. Other finds are Arabic coins and glassware. The finds that were discovered by the early European settlers in the hills around the ruins include wooden bowls with crocodile patterns , but also Chinese ceramics from the Ming dynasty and Assamian jewelry. It is not yet known with which Chinese fleets the ceramics came to the East African coast and from there on the trade routes to Greater Zimbabwe.

Political importance

The ruins are a very important archaeological site of southern Africa. Initially, the evaluations were carried out by Rhodesian Ancient Ruins Ltd. difficult, a commercial group of treasure hunters who had received official digging rights. Later excavations, especially of RN Hall, destroyed many traces of the Shona culture, as the researchers of European origin wanted to prove that the building of Old Zimbabwe did not go back to black Africans. During British rule in Rhodesia , as Zimbabwe was called until the black majority took over, the black African origin of the ruins was always disputed. In addition to the Phoenicians , other, exclusively fair-skinned people (or at least white men) were also referred to as founders.

1970 left the two archaeologists Roger Summers, employee at the National Museum (1947-1970), and Peter Garlake (1934-2011), conservationist in Rhodesia (1964-1970), the then Rhodesia because they worked under the white minority government under Ian Smith could no longer reconcile with their scientific way of working. 1978 Garlake lecturer was in anthropology at the University College of London University .

Robert Mugabe had a personality cult based on African traditions and traces his origins back to the kings of Greater Zimbabwe. That's why he was dubbed Our King . His services to the country and his heroic deeds during the war of liberation were celebrated in poems and hymns of praise that must be learned in schools. Furthermore, he was awarded numerous honorary titles that the kings of Shona had carried in earlier times .

Current attempts to connect the builders of Greater Zimbabwe with civilizations outside of Africa come from researchers who are trying to establish a connection between Semitic groups and the Lemba through genetic comparisons . However, the genetic characteristics date to around 3000 to 5000 BP , well before Greater Zimbabwe.

Infrastructure and tourism

Tourist development

The entire area is managed by the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe , with Godfrey Mahachi being the on-site director. The individual structures are accessed by paths and are explained in several places by boards. A guest house of the national park administration and a campsite are available to visitors. Despite the difficult political and economic situation, foreign guests continue to visit the site.

However, after the country reform program in 2000, tourism in Zimbabwe has steadily declined. After increasing during the 1990s, with 1.4 million tourists in 1999, the number of visitors fell by 75 percent in December 2000, with less than 20 percent of hotel rooms occupied in the same year. The total number of visitors to Zimbabwe in 2008 was 223,000 tourists. Since the ruins of Greater Zimbabwe is the second most visited main attraction in Zimbabwe after the Victoria Falls, this has a particularly positive impact on the local tourism industry. Local tourists were deterred from visiting by hyperinflation and the lack of basic services, while foreign visitors by the unstable political situation. More than 12,000 people lost their jobs due to the drop in tourist visits by over 70 percent in 2001. According to the information from the Foreign Office, Zimbabwe has "almost completely lost the former charm of a pleasant tourist and travel destination with a good infrastructure."

Up until the year 2000, the incoming visitors spent 2.5 hours in the facility sightseeing. The most visited point was the Great Enclosure, followed by the gift shop and then the Hill Complex. Within the great enclosure, the conical tower was most frequently visited. As a result of the political development in Zimbabwe, the number of visitors, which last stood at 120,000 in 1999, fell to 15,442 by 2008. For 2010, 30,000 visitors were expected. List of paying visitors:

- 1980: 42,632

- 1981: 56.027

- 1989: 84.960

- 1990: 87.820

- 1991: 88.296

- 1992: 70.720

- 1993: 102.877

- 1994: 111,649

- 1995: 120.993

- 1996: 91,652

- 1997: 88.122

- 1998: 153.343

- 1999: 120,000

- 2006: 20,000

- 2007: 27,587

- 2008: 15,442

- 2010: approx. 30,000

- 2013: 55,170

- 2014: 58,180

- 2018: 72,284

Greater Zimbabwe receives operational funding from the US government for the security forces and partly for the museum. The Culture Fund of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) provides additional funding for the development of the site. The National Public Investment Fund, which is based on a 50-50 rule, is helping to set up the infrastructure. Unesco occasionally made funds available in the 1990s, for example for fire fighting.

Museum-like Shona village

To the east of the ruins, a museum model of a 19th-century Shona village was built in 1986 as an additional attraction for tourists. The representation of the components, the staff and the activities of village life were described as not very authentic. In particular, the use of modern tools in demonstrating traditional crafts and modern clothing were criticized. Some researchers describe a confusion among visitors and rate the impact on the World Heritage site negatively.

Visitors to the ruins

The ruins have been a frequent destination for travelers since they were first announced by Mauch and Bent. Cecil Rhodes visited the ruins as early as 1890. Queen Elizabeth II visited the complex twice, initially on a three-month trip to South Africa in April 1947, together with her father, King George VI. , her mother Elizabeth and her sister Princess Margaret and again in October 1991. On July 12, 1993 Princess Diana was visiting Greater Zimbabwe and on May 20, 1997 Nelson Mandela .

Transport links

There are many local bus services between the ruins and the bus terminal in Masvingo. There are also direct bus connections ( coaches ) to Bulawayo or Harare from the ruins . The nearest international airports are Harare Airport to the north and Johannesburg Airport to the south .

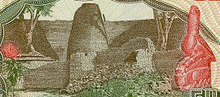

Others

| From the introduction of the Zimbabwe currency notes after independence in 1980 to the suspension of the currency in 2008, the ruins were depicted on the Z $ 50 note, which, however, has hardly been used since 2000 due to the hyperinflation . One of the Zimbabwe birds was the motif of the 1 cent coin.

In addition, a Z $ 1 stamp was issued to include the ruins in the 1986 World Heritage List, on which the large enclosure is depicted. Another postage stamp, this time with the conical tower and bird of Zimbabwe, was released in 2005. |

|

|

See also

- Dhlodhlo , Naletale , Khami and Ziwa (smaller ruins in the country of Zimbabwe)

- List of archaeological sites in southern Africa

Directory of literature, maps and documentation

literature

- David N. Beach: The Shona and Zimbabwe 900-1850. Heinemann, London 1980 and Mambo Press, Gwelo 1980, ISBN 0-435-94505-X .

- James Theodore Bent: The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland. London 1896.

- Kunigunde Böhmer-Bauer: Great Zimbabwe - An ethnological investigation. Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-89645-210-X

- Andries Johannes Bruwer: Zimbabwe: Rhodesia's Ancient Greatness. Johannesburg 1965.

- Shadreck Chirikure, Innocent Pikirayi: Inside and outside the dry stone walls: revisiting the material culture of Great Zimbabwe. In: Antiquity. 82 (2008), pp. 976-993. ( pdf )

- Graham Connah: African Civilizations: Precolonial Cities and States in Tropical Africa. Cambridge 1987 (pp. 183-213 on Greater Zimbabwe and gold mining). (Revised edition Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-26666-1 )

- Joost Fontein: The Silence of Great Zimbabwe: Contested Landscapes and the Power of Heritage. UCL Press, New York, NY 2006, ISBN 1-84472-122-1 . ( Review in English, by Jonathan R. Walz, University of Florida)

- Jost Fontein: Silence, Destruction and Closure at Great Zimbabwe: local narratives of desecration and alienation. In: Journal of Southern African Studies. 32 (4) (2006), pp. 771-794. doi: 10.1080 / 03057070600995723

- Peter S. Garlake: Zimbabwe. Goldland of the Bible or a symbol of African freedom? Bergisch Gladbach 1975, ISBN 3-7857-0167-5 .

- Peter S. Garlake: Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Bloomington 1987, ISBN 0-941934-51-9 . ( pdf , 3.9 MB)

- Peter Hertel: To the ruins of Zimbabwe. Gotha 2000, ISBN 3-623-00356-5 .

- Thomas N. Huffmann: Snakes and Crocodiles: Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press 1996, ISBN 1-86814-254-X

- Siegbert Hummel: Zimbabwe: the still unsolved archaeological riddle of the African continent; new ethnological, cultural-historical and linguistic assumptions. Ulm 1999, ISBN 3-931997-10-3 .

- Edward Matenga: The Soapstone Birds of Great Zimbabwe. Symbols of a nation. Harare 1998, ISBN 1-77901-135-0 .

- Edward Matenga: Archaeological Figurines from Zimbabwe. Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis, Uppsala 1993.

- Heinrich Pleticha (Ed.), Zimbabwe. Voyages of discovery into the past. Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-522-60620-5 .

- Herbert WA Sommerlatte: Gold and ruins in Zimbabwe. From diaries and letters of Swabian Karl Mauch (1837–1875). Gütersloh 1987, ISBN 3-570-07918-6 .

- Shadreck Chirikure, Thomas Moultrie, Foreman Bandama, Collett Dandara, Munyaradzi Manyanga: What was the population of Great Zimbabwe (CE1000 - 1800)? In: PLoS ONE 12/6 (2017), e0178335 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0178335 .

- Kevin Shillington: History of Africa. Revised 2nd Edition, Macmillan Education, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-333-59957-8 .

- Joseph O. Vogel: Great Zimbabwe: the Iron Age in South Central Africa. Garland, New York et al. a. 1994, ISBN 0-8153-0398-X .

cards

- Digital overview maps (English)

- TK 250 SF-36-1 Masvingo (English)

- 3D models in JSTOR's African Cultural Heritage Sites and Landscapes database (English)

Films and documentaries

- 1919: "Isban Israel", film, director: Joseph Albrecht

- 1982: "Terra X - Riddle of Old World Cultures" (43 min.), Directors: Gottfried Kirchner , Peter Baumann , with Dirk Steffens , Maximilian Schell and Frank Glaubrecht .

- 1995: "Lost Civilizations" (43 min.), Director: Jenny Barraclough, with Hans-Peter Bögel (English).

- 1996: "Great Railway Journeys: Great Zimbabwe to Kilimatinde" ( Henry Louis Gates Jr. and his family travel from Zimbabwe to Tanzania), directed by Nick Shearman

- 2005: "Digging for the Truth: Quest for King Solomon's Gold" (45 min.), Director: Brian Leckey, with Josh Bernstein (English).

- 2009: “Mysterious Kingdoms: Zimbabwe” (43 min.), Directed by Ishbel Hall , with Gus Casely-Hayford

- 2010: "BBC - Lost Kingdoms of Africa S01E03 Great Zimbabwe" (51 min.), With Gus Casely-Hayford

- 2016: Adventure archeology: Greater Zimbabwe: Uncovering a ruined city. (27 min.), Directed by Agnès Molia, Mikael Lefrançois

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- NMM of Zimbabwe (English)

- Peter Tyson: Mystery of Great Zimbabwe (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Innocent Pikirayia, Shadreck Chirikureb: Zimbabwe Plateau and Surrounding Areas. In: Encyclopedia of Archeology. Pp. 9-13. doi: 10.1016 / B978-012373962-9.00326-5

- ↑ Manu Ampim: Great Zimbabwe: A History Almost Forgotten Toronto 2004.

- ^ CJ Zvobgo: Medical Missions: A Neglected Theme in Zimbabwe's History, 1893-1957. In: Zambezia. 13 (2), (1986), pp. 109–118, here p. 110 pdf (English)

- ↑ a b World Heritage Sites and Suitable Tourism, Situational Analysis: Great Zimbabwe WHS pdf ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Webber Ndoro: The preservation of Great Zimbabwe. Your Monument our Shrine (ICCROM Conservation studies 4). Rome 2005, p. 22 pdf ( Memento of the original dated December 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ↑ Innocent Pikirayi: The Zimbabwe culture: origins and decline of southern Zambezian states. 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ Webber Ndoro: The preservation of Great Zimbabwe. Your Monument our Shrine (ICCROM Conservation studies 4). Rome 2005, p. 57 pdf ( Memento of the original dated December 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ^ Herbert WA Sommerlatte: Gold and Ruins in Zimbabwe. From diaries and letters of Swabian Karl Mauch (1837–1875). Gütersloh 1987, pp. 156-171.

- ↑ Michel Lafon: Shona Class 5 revisited: a case against * ri as Class 5 nominal prefix. (PDF; 797 kB) In: Zambezia. 21: 51-80 (1994).

- ↑ Lawrence J. Vale: Mediated monuments and national identity. In: Journal of Architecture. 4 (1999), pp. 391-408 doi: 10.1080 / 136023699373774 .

- ↑ Peter Garlake: Great Zimbabwe: New Aspects of Archeology. London 1973, p. 13.

- ↑ M. Sibanda, H. Moyana et al: The African Heritage. History for Junior Secondary Schools. Book 1. Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1992, ISBN 0-908300-00-X .

- ^ The Ruins of Great Zimbabwe. (English)

- ^ Neville Jones: Further Excavations at Gokomere, Southern Rhodesia. In: Man. Vol. 32 (Jul., 1932), pp. 161 f.

- ↑ Shadreck Chirikure, Innocent Pikirayi: Inside and outside the dry stone walls: revisiting the material culture of Great Zimbabwe. In: Antiquity. 82 (2008), pp. 976-993. pdf ( Memento of the original from July 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Thomas N. Huffman: Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. In: Journal of Anthropological Archeology. 28, H. 1, (2009), pp. 37-54. doi: 10.1016 / j.jaa.2008.10.004

- ^ Thomas N. Huffman: Climate change during the Iron Age in the Shashe-Limpopo Basin, southern Africa. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 35, H. 7 (2008), pp. 2032-2047. doi: 10.1016 / j.jas.2008.01.005

- ↑ Greater Zimbabwe (11th – 15th centuries) The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Shadreck Chirikure, Thomas Moultrie, Foreman Bandama, Collett Dandara, Munyaradzi Manyanga: What was the population of Great Zimbabwe (CE1000 - 1800)? In: PLoS ONE 12/6 (2017), e0178335 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0178335 .

- ↑ Reinhold Jordan: An Arab coin from the 14th century in Zimbabwe. In: Monetary History News. 14: 155-157 (1979).

- ↑ BBC report (English)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Peter S. Garlake: Zimbabwe. Goldland of the Bible or a symbol of African freedom? Bergisch Gladbach 1975, pp. 61-69.

- ^ Edward Powys-Mathers: Zambesia: England's El Dorado in Africa; being a description of Matabebland and Mashonaland . London: King, Sell & Reilton 1891

- ↑ Peter Hertel: To the ruins of Zimbabwe. Gotha, Klett Perthes 2000, ISBN 3-623-00356-5 , pp. 154-160.

- ↑ Communications from Justus Perthes' Geographischer Anstalt about important new researches in the whole field of geography. 16 (1870).

- ^ Willi Posselt: The Early Days of Mashonaland and a Visit to Great Zimbabwe Ruins. In: NADA. 2 (1924), pp. 70-74.

- ^ A b Richard Nicklin Hall, WG Neal: The ancient ruins of Rhodesia: (monomotapæ imperium). Methuen, London 1902. (Reprint: Negro University Press, New York 1969, ISBN 0-8371-1275-3 )

- ↑ James Theodore Bent: The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland: being a record of excavation and exploration in 1891. Longmans, Green & C., London 1892. (Reprint: Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, NY 1971, ISBN 0-8369-8528 -1 )

- ↑ a b c d e Peter S. Garlake: Zimbabwe. Goldland of the Bible or a symbol of African freedom? Bergisch Gladbach 1975, pp. 70-82.

- ↑ Free Essay: Great Zimbabwe

- ↑ Joachim Zeller: Picture School of the Herrenmenschen: Colonial Reklamesammelbilder. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-499-0 , p. 158.

- ↑ These travel reports from 1899 to 1901 are printed in: Carl Peters: In the gold land of antiquity: Research between Zambesi and Sabi. Featuring 50 original Tennyson Cole illustrations, made on the spot. Lehmann, Munich 1902. (Reprint: Time Life Books, Amsterdam 1982, ISBN 90-6182-752-3 )

- ^ Richard Nicklin Hall: Prehistoric Rhodesia. London 1909, p. 246.

- ↑ a b c d e Peter S. Garlake: Zimbabwe. Goldland of the Bible or a symbol of African freedom? Bergisch Gladbach 1975, pp. 83-120.

- ↑ Solomon's Mines. In: The New York Times . April 14, 1906, p. RB241.

- ↑ David Randall-MacIver: The Rhodesia Ruins: their probable origins and significance. In: The Geographical Journal. 27 (1906), No. 4, pp. 325-336 . doi: 10.2307 / 1776233

- ^ Franklin White: Notes on the Great Zimbabwe Elliptical Ruin. In: The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 35 (1), (1905), pp. 39-47. jstor

- ^ Gertrude Caton-Thompson: The Zimbabwe Culture: ruins and reactions. Oxford 1932.

- ↑ Webber Ndoro: The preservation of Great Zimbabwe. Your Monument our Shrine (ICCROM Conservation studies 4). Rome 2005, p. 29 pdf ( Memento of the original dated December 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ^ Huffman, TN, JC Vogel: The chronology of Great Zimbabwe. In: South African Archaeological Bulletin. 46: 61-70 (1991). ( pdf )

- ↑ Roger Summers: Dating of the Zimbabwe ruins. In: Antiquity. 29 (1955), p. 107.

- ↑ Edward Matenga: The Soap Stone Birds of Great Zimbabwe. Symbols of a Nation. Harare 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ Peter Garlake: Great Zimbabwe Described and explained '. Harare 1994, pp. 39-47.

- ↑ a b Peter Garlake: Great Zimbabwe described and explained. Harare 1994, pp. 31-37.

- ↑ Peter Garlake: Great Zimbabwe Described and explained '. Harare 1994, p. 35.

- ↑ a b c d Peter Garlake: Great Zimbabwe described and explained. Harare 1994, p. 58 f.

- ^ William J. Dewey: Repatriation of a Great Zimbabwe Bird. Tennessee 2006. pdf ( Memento of the original from November 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ↑ Dawson Munjeri: The reunification of the Stone Bird of Great Zimbabwe at at exhibition of the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, Belgium and its return from Germany to Zimbabwe. pdf (english)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Edward Matenga: The Soapstone Birds of Great Zimbabwe. Symbols of a Nation. Harare 1998, pp. 33-42.

- ↑ Antoon de Baets: Censorship of Historical Thought: a World Guide 1945-2000. Greenwood Press, London 2002, ISBN 0-313-31193-5 , pp. 621-625. pdf ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Marc G. Thomas, Tudor Parfitt et al.: Y Chromosomes Traveling South: The Cohen Modal Haplotype and the Origins of the Lemba - the "Black Jews of Southern Africa". In: The American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (2000), H. 2, pp. 674-686. doi: 10.1086 / 302749

- ^ David McNaughton: A Possible Semitic Origin for Ancient Zimbabwe. In: http://dlmcn.com/anczimb.html Mankind Quarterly 52 (2012), pp. 323-335.

- ↑ Lewis Machipisa: Sun sets on Zimbabwe tourism. In: BBC News of March 14, 2001

- ↑ a b c Godfrey Maravanyika: Visitors return to Great Zimbabwe. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Zimbabwe journalists. May 27, 2010

- ^ David Blair: Visitors abandon the Great Ruins. In: The Telegraph. May 29, 2001. (English)

- ↑ Travel advice from the Federal Foreign Office

- ↑ a b Data from 1989 to 1999 from July to June according to Webber Ndoro: The preservation of Great Zimbabwe. Your Monument our Shrine (ICCROM Conservation studies 4). Rome 2005, p. 80 pdf ( Memento of the original dated December 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ↑ Hamo Sassoon: The Preservation of Great Zimbabwe. Paris 1982 pdf (English)

- ↑ a b Kate Rivett-Carnac: Cultural world heritage site scan: Lessons from four sites. Development Bank of Southern Africa 2011, p. 15 pdf ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Tatenda Chitagu: Great Zimbabwe records upsurge in tourism activity , in: NewyDay of April 20, 2015

- ↑ Tatenda Chitagu: Great Zimbabwe records upsurge in tourism activity , in: NewyDay of April 20, 2015

- ↑ Tourism Trends and Statistics Report 2018, p. 50.

- ↑ Webber Ndoro, Gilbert Pwiti: Marketing the past: the "Shona village" at Great Zimbabwe. In: Conservation and management of archaeological sites. 2 (1), (1997), pp. 3-8. ISSN 1350-5033

- ↑ Gilbert Pwiti: Let the ancestors rest in peace? New challenges for cultural heritage management in Zimbabwe. In: Conservation and management of archaeological sites. 1 (3) (1996), pp. 151-160. ISSN 1350-5033

- ↑ Queen Elizabeth II Remembers Fondly Zimbabwe. ( Memento of the original from March 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Radio VOP. March 15, 2011

- ^ Queen Elizabeth in Zimbabwe. (English)

- ↑ Lady Diana in Zimbabwe. (English)

- ↑ Image of the stamp from 1986 (English)

- ↑ Illustration of the stamp from 2005 (English)

- ↑ Neil Parsons: Investigating the Origins of The Rose of Rhodesia, Part II: Harold Shaw Film Productions Ltd ( Memento of the original from May 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 2009 (English)

- ↑ Terra X - Puzzles of Ancient World Cultures. Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ^ Lost Civilizations. Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ^ Great Railway Journeys. Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ↑ Quest for King Solomon's Gold. Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ↑ BBC - Lost Kingdoms of Africa

Coordinates: 20 ° 16 ′ S , 30 ° 56 ′ E