Bladder cancer

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C67 | Malignant neoplasm of the urinary bladder |

| D09.0 | Carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

As a bladder cancer (bubbles carcinoma ) generally are from the bladder outgoing malignant tumors designated (malignant tumors). The causes of bladder cancer are chronic inflammation (including parasite infections), tobacco consumption , the ingestion of certain chemical substances (for example aromatic amines such as 2-naphthylamine ), radiation exposure and defense-suppressing drugs . Depending on its extent, bladder cancer is treated with transurethral resection of the urinary bladder (TUR-B) , complete removal of the bladder, local chemotherapy or radiation therapy in combination with systemic chemotherapy. The chances of recovery are good if cancer is discovered early, but low in the case of an extensive disease with metastases .

Frequency (epidemiology)

Bladder carcinoma is (as of 2006) the fifth most common malignant tumor disease in humans. The risk for men of developing bladder cancer is around three times higher than the risk for women. Bladder cancer is the fourth most common tumor in men and the tenth most common in women. Around 30 new cases per year were counted for every 100,000 men and 8 new cases per year for 100,000 women. Around 16,000 new cases of bladder cancer occurred in the Federal Republic of Germany each year.

| Incidence | Men | Women |

| New cases only invasive tumors |

11,680 | 4,170 |

| with precursors also non-invasive papillary carcinomas and in situ tumors |

22,430 | 7,100 |

| raw morbidity rate | 29.4 | 10.1 |

| standardized disease rate | 18.2 | 4.9 |

| median age of onset | 74 | 76 |

Notes: The raw disease rate indicates the annual number of new diseases per 100,000 population. The standardized morbidity rate takes into account the age of the sick and puts it in relation to a European age distribution of the population. The table shows that a large proportion of the preliminary stages never develop into an invasive carcinoma. This is due to the slow development of precancerous stages and the high median age of onset of patients who die of other diseases before the transition to invasive carcinoma.

The average age of occurrence varies depending on the source, in Germany 76 years for women and 74 for men (as of 2014). Diseases in patients younger than 50 years are rare. In industrialized countries bladder cancer is approximately six times higher than in developing countries , the incidence of the disease increased during the 20th century as a whole. At the initial diagnosis, about 75% of the cases are found to be superficial carcinoma. In 20% of the cases it is already invasive and in 5% there are already metastases . Bladder cancer often occurs in different places within the bladder at the same time. After successful healing, the tumor often recurs ( relapse ).

causes

Aromatic amines

Contact with aromatic amines ( 2-naphthylamine , benzidine ) is the longest known risk factor. In many professions, contact with such cancer-causing substances is possible and bladder cancer is recognized as an occupational disease . These include workers in the chemical, steel and leather industries, car mechanics, as well as dental technicians and hairdressers. The aromatic amines are made water-soluble in the liver by coupling with hydroxyl groups and glucuronic acid so that the body can excrete them in the urine. In doing so, however, they develop a carcinogenic potential. Aromatic amines can be inactivated by the enzyme N-acetyltransferase . Some people who have a higher enzyme activity due to a genetic polymorphism have a lower risk of developing bladder cancer. According to a Spanish study, these polymorphisms are so widespread that they could play a role in around 31% of bladder cancers.

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco smoking is the number one risk factor for bladder cancer, which is not widely known by the public. In a survey of urological patients, almost all of them indicated a link between smoking and lung cancer , but only 34% knew that bladder cancer can be caused by smoking. The amount of tobacco products consumed in total correlates linearly with the risk of developing bladder cancer. It increases by two to six times depending on the consumption behavior and duration. The cause is considered to be the occurrence of aromatic amines such as 2-naphthylamine in smoke. Whether stopping nicotine abuse after the onset of cancer can improve the prognosis of the disease or prevent its recurrence has not yet been conclusively clarified (2002).

According to a study from 2011, tobacco smoking is responsible for 50 percent of all bladder cancers in men and 52 percent in women. A 4-fold increased risk of illness was calculated for active smokers and a 2.2-fold increased risk for former smokers.

Chronic inflammation

Chronic inflammation in the bladder area also increases the risk of malignant neoplasm. These include long-standing bladder stone problems and chronic urinary tract infections . In Africa and parts of the Arab world, parasite-induced schistosomiasis is an important risk factor for the development of bladder cancer. Carcinomas caused by inflammation are usually squamous cell carcinomas. The cause is assumed to be the formation of nitrosamines as part of the inflammatory reaction.

Irradiation

Likewise, one is radiation therapy in the pelvic area, a risk factor for bladder cancer.

Medication

Other iatrogenic risk factors are some drugs. Chlornaphazine , a drug used to treat polycythemia vera , and phenacetin , a pain medication, promote the development of bladder cancer. The first mentioned active ingredient has not been on the market since 1963, the second mentioned was withdrawn from the market in 1983. Another drug used is the immunosuppressant cyclophosphamide , which can cause hemorrhagic cystitis and thereby promote bladder cancer. When used correctly together with the active ingredient Mesna , however, the risk of cancer is negligible. The cytostatic chloronaphazine , which was used in the treatment of polycythemia vera until 1963 , caused bladder carcinomas in around a third of the patients treated.

The oral anti-diabetic drug pioglitazone is also suspected of causing bladder cancer. The US Food and Drug Administration published updated safety information in 2011 and 2016, indicating the potential risk.

Sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners such as saccharin and cyclamate have been shown to increase the incidence of bladder cancer in animal studies. The effect in humans is controversial as the majority of studies in humans have not proven this effect. In addition, the studies in animal experiments are not relevant insofar as the substances were injected directly into the bladder with a cannula. The observed tumors are more likely to be associated with penetration of the needles than with the sweetener. Research on the consumption of coffee is also not clear to date.

water

A Spanish case control study found that chlorinated water increased the risk of bladder cancer. According to this, people who drank chlorinated water have a 35 percent increased risk of bladder cancer. Swimming in chlorinated water actually increases the risk by 57 percent. Studies with large numbers of cases from the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) came to the conclusion that arsenic contamination in drinking water increased the risk of bladder cancer.

nutrition

Statistically, a high total consumption of fruit has a slightly protective effect against bladder cancer. The exact mechanism by which this protective effect takes place has not yet been clarified. A protective effect of vitamin E is debated in the literature, but has not been proven.

Symptoms

The classic symptom of bladder cancer is the admixture of blood in the urine without causing pain. This can be seen with the naked eye ( macrohematuria ) or it can only be noticed in the laboratory when examining the urine ( microhematuria ). In rare cases, the tumor can also cause pain if the urethra is blocked by clotted blood. In the late stage, it can be obtained by a large tumor in a urinary or renal congestion come (when the tumor moves the Blasenaus- or input) and the associated pain in the area of the bladder or the flanks lead. If there are bone metastases , these are often noticeable as pain in the affected parts of the skeleton.

Diagnosis

Since most cancers are characterized by hematuria , a cause of this symptom in the kidney must first be ruled out. An ultrasound examination of the kidneys and urinary bladder is recommended . In some cases, a bladder tumor can be identified by this examination. Likewise , indications of bladder carcinoma can be obtained through a urogram , in which intravenous contrast medium is excreted in the urine and the kidneys and urinary tract can be visualized in several x-rays . A computed tomography (CT) can detect the tumor. It can also be used to search for enlarged lymph nodes . However, it only represents lymph nodes from a size of 1 cm and is therefore of limited diagnostic significance and of little value in bladder carcinoma. For magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) basically the same thing applies. Another measure is a cytodiagnostic examination ( urine cytology ). Exfoliated surface cells in the urine that come from the bladder and urinary tract are examined microscopically. This investigation has a sensitivity of around 80–90% for poorly differentiated tumors .

With the liquid biopsy of the urine it could be shown that immune cells found in urine were more representative for the diagnosis of bladder cancer than immune cells from the blood, which suggests that the procedure using urine instead of blood can contribute to to closely examine the response to immunotherapy . T lymphocytes are not normally found in the urine in healthy individuals. It is crucial that the T cells match those in the tumor environment of the bladder carcinoma, regardless of the cancer stage and the course of treatment. Immunotherapy shows promise for cancers that are difficult to treat, but only 30-40 percent of patients respond to immunotherapy. These can thus be identified.

If the tumor is still well differentiated, the chance of discovering the cancer is not satisfactory. With the test for the nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP 22) released in the urine , a tumor marker for bladder carcinoma is available. The test has a higher sensitivity than the normal urine cytology, but a lower specificity . It can thus increase the likelihood of detecting the disease at an early stage in combination with conventional diagnostic methods. In contrast, the IGeL monitor of the MDS (Medical Service of the Central Association of Health Insurance Funds) rates the NMP2 test for the early detection of bladder cancer as "tending to be negative" after systematic research of the scientific literature. Even for high-risk groups, the test does not appear to be very accurate and does not reveal any indications of any benefit. In addition, early detection examinations always carry the risk of triggering false alarms and leading to unnecessary examinations and treatments. If the results are normal in normal white light endoscopy, photodynamic blue light endoscopy may under certain circumstances provide information about tumor foci. If there is still a suspicion of a tumor (urine cytology, marker) despite the normal tissue findings, a more detailed examination of the upper urinary tract is essential, as these are also lined with urothelium.

The final diagnosis is made after endoscopic removal ( TUR-B ) of the tumor through a tissue examination . During the first operation, in addition to the removal of endoscopically clear findings, four biopsies should also be taken from normal-appearing bladder mucosa and one from the part of the urethra that runs in the prostate , so as not to overlook a carcinoma in situ .

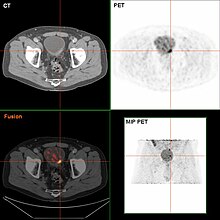

After the operation, staging should take place to answer the question of the local finding outside the bladder and the presence of metastases . Bladder cancer most commonly metastasize to the lungs, liver, and skeleton via the bloodstream. A CT scan of the pelvis to look for enlarged lymph nodes, an ultrasound scan of the liver, an x-ray of the chest to look for metastases in the lungs, and a scintigram of the bones are recommended. A PET examination has only unreliable informative value for bladder cancer.

classification

The classification of mucosal tumors follows the TNM classification . Bladder carcinoma is no exception. The classification is roughly outlined in the following table:

| T | Ta | Non-invasive papillary carcinoma in situ of the urothelium |

| Tcis | Non-invasive carcinoma in situ | |

| T1 | Growing under the mucous membrane into the submucosal connective tissue (sub-forms: T1a: above the mucous membrane muscle layer; T1b: below the mucous membrane muscle layer) | |

| T2 | Growing into the muscle layer of the urinary bladder (sub-forms: T2a: inner half, T2b: up to the outer half) | |

| T3 | Outgrowth beyond the muscle layer of the urinary bladder (sub-forms: T3a: only visible under a microscope, T3b: visible to the naked eye) | |

| T4 | Growing into neighboring organs (sub-forms: T4a: prostate, uterus, vagina, T4b: pelvic or abdominal wall) | |

| N | N0 | No local lymph nodes involved |

| N1 | Single affected lymph nodes smaller than 2 cm | |

| N2 | single lymph nodes 2 to 5 cm in diameter or several affected lymph nodes <5 cm | |

| N3 | Lymph nodes over 5 cm | |

| M. | M0 | No distant metastases detected |

| M1 | Distant metastases detected (sub-forms: M1a: metastases in non-regional lymph nodes; M1b: other distant metastases) |

| Stage 0a | Ta | N0 | M0 |

| Stage 0is | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Stage I. | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T2 or T2b | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIIA | T3a or T3b or T4a | N0 | M0 |

| T1-4a | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage IIIB | T1-4a | N2 or N3 | M0 |

| Stage IVA | T4b | N0 | M0 |

| any T | any N | M1a | |

| Stage IVB | any T | any N | M1b |

In addition to the classification of the extent of the tumor, grading is also carried out as part of a tissue examination . Since 2004, according to the WHO criteria, grading has only included two options, either high or low grade. Low-grade carcinomas are better differentiated and have a better prognosis than high-grade carcinomas with many atypias. When grading, the worst differentiated proportion of the tumor counts, regardless of its proportion in the total tumor. In addition, a classification is common in German-speaking countries, which divides the tumors from G1 to G3 according to the degree of differentiation. G1 represents a relatively less atypical tumor and G3 a very poorly differentiated tumor. G2 lies between these two extremes.

pathology

The most common malignant tumor found in the urinary bladder is urothelial carcinoma originating in the urothelium of the urinary bladder . Squamous cell carcinoma can also occur. These arise on the basis of a metaplasia of the normal urothelium to squamous epithelium. This process is triggered by the chronic inflammation caused by schistosomiasis , which is endemic to parts of Africa and the Arab world. Glandular adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas are very rare . Sarcomas can also very rarely develop from the muscle layer of the urinary bladder .

Macroscopy

With the naked eye, bladder tumors can be macroscopically divided into two types. On the one hand there are tumors that extend flat over the surface of the organ (solid tumors), on the other hand those that grow wart-like (papillary) into the lumen of the urinary bladder. The visual inspection gives no indication of the invasiveness of the tumor.

histology

Histologically , the most common type shows urothelial tissue with “cancer-typical” atypia . The cell nuclei are changed, stained more intensely, do not look the same and are different from one another in their polarity . In its entirety, the epithelium shows an abolition of the stratification and a lack of the maturation observed in healthy subjects from the lower to the near-surface layer. The remaining types are characterized by non-existent types of surface tissue in the urinary bladder, which is also atypically changed.

The penetration of the tumor into the deeper layers of the urinary bladder usually takes place in small groups of cells. These are often surrounded by an inflammatory reaction from lymphocytes and plasma cells .

A special form of urothelial carcinoma is the "nested variant". This shows only slight cell atypia and also immunohistologically no particular abnormalities, but often grows malignantly into the surrounding tissue. It can be recognized by the nest-like arrangement of tumor cells. The comparatively harmless morphological appearance can make diagnosis more difficult if the invasion into deeper layers is not recorded by the biopsy material.

Immunohistochemistry

The cover cells of the urothelium also develop cytokeratin in healthy people . As with other carcinomas, cytokeratin expression can also be demonstrated immunohistochemically in bladder tumors . The urothelial character of the tumor can be proven with an antibody directed against the protein uroplakin . The degree of differentiation and the possible malignancy of the tumor cells can be estimated, among other things, by staining with the proliferation marker Ki-67, which marks cells that are dividing. In general, the more cells that are dividing, the more aggressive the tumor will be. An increased accumulation of p53 protein in the cell nucleus also has an unfavorable prognostic significance.

Molecular pathology

The division between solid and papillary tumors, already made with the naked eye, is reflected on the genetic level. The papillary tumors show changes on both arms of chromosome 9. The solid tumors show a mutation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 on chromosome 17 as the main genetic change .

therapy

Treatment of the tumor

The therapy is carried out depending on the stage, taking into account the living conditions of the patient (biological age, comorbidities , life expectancy ) using various methods.

The carcinoma in situ , by the instillation of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin treated (BCG) into the bladder. These are attenuated tuberculosis pathogens . These trigger an inflammatory reaction in the urinary bladder, which can destroy the tumor cells. Treatment includes one to two cycles. Long-term success is achieved in around two thirds of patients. With three or more cycles, in 2008 even 90.8% were relapse-free after 3 years. The long-term therapeutic success should be based on the microscopic examination of detached bladder cells from the urine. In the event of a relapse or treatment failure, surgical removal of the bladder is indicated.

Superficial tumors (pTaG1 to pT1G2) are removed by a TUR-B . The instillation of chemotherapeutic agents such as mitomycin C is recommended as part of the treatment of superficial tumors . This should be done immediately after the operation. Patients with poor grading and evidence of atypical cells in the initial random biopsies have a higher risk of recurrence. Therefore, an intensive instillation therapy should be carried out with them, which, depending on the therapy scheme, can extend over several months. Lifelong follow-up with endoscopic and cytological controls is mandatory.

The pT1G3 tumor represents a special case. The tumor is not yet muscle invasive, but has a high risk of metastasis due to its poor differentiation. Radical bladder removal is the method of choice, especially if there is a relapse .

Muscle-invasive bladder carcinomas are treated with radical bladder removal. Numerous surrounding organs or parts of organs have to be removed, in addition the uterus , ovaries and fallopian tubes in women, and the prostate and seminal vesicles in men . If the urethra is also affected by the tumor, it must be removed in both sexes. Since this is a comparatively large procedure, the death rate during the procedure is 2-3% even if it is performed optimally. The effect of chemotherapy before and after surgery is still the subject of studies. In the case of lymph node metastases , removal of the lymph nodes up to the main artery fork is recommended.

As an alternative to radical surgery, radiation therapy or chemoradiation can be considered. Urothelial carcinomas are among the radiation-sensitive tumors and can be destroyed with good success with radiation. Radiation therapy, possibly in combination with radiation-intensifying chemotherapy, achieves the same survival rates as radical surgery, but around 70% of all patients can maintain their bladder with good bladder function. This can represent an alternative to a surgical approach, especially in patients for whom an operation has to be assessed critically due to age or previous illnesses.

Metastatic bladder carcinoma is treated with chemotherapy as standard . There are different therapy schemes in which a combination of several active ingredients is administered in each case. The various combinations differ in their effectiveness and in the frequency and occurrence of side effects. Since combination therapy has proven to be superior to treatment with only one preparation, the latter has become obsolete. In individual cases, surgical removal of a metastasis can also be useful. The use of new drugs that specifically block receptors on tumor cells, e.g. B. trastuzumab and lapatinib , are currently in clinical trials. Chemotherapy can also be carried out in patients whose bladder removal appears too risky due to old age or poor general health. The survival rate and time are lower than in operated patients.

Urinary diversion after removal of the bladder

In patients who have had their bladder removed ( cystectomy ), there are several ways to drain their urine. A distinction is made between continents and so-called wet discharges.

One possibility is the creation of a new bladder as a urinary bladder replacement. To do this, a segment of the small intestine ( ileum ) that has been switched off is sutured into a ball and connected to the ureter and the urethra. Since the bladder sphincter is retained when the bladder is removed, a high percentage of the patients are continental and excrete the urine via the urethra as usual.

Another method is the implantation of the ureters in the lower section of the large intestine ( colon sigmoideum ) according to Coffey. The urine is then excreted together with the stool via the intestinal outlet ( cloaca ). This method has largely been abandoned in favor of the Mainz pouches. At the junction between the ureter and the intestine, the formation of carcinomas can be observed after around a decade.

The urine can also be drained through an artificially created outlet ( urostoma ) in the abdominal wall. For this purpose, a so-called ileum conduit is created: a segment is removed from the small intestine ( ileum ), connected to the ureters and connected to the stoma. A replacement bladder made up of parts of the intestine can also be diverted via a stoma; it is then referred to as a pouch. These methods are an option for patients who have had their urethra removed as part of the operation.

In all discharges with intestinal segments, the acid-base balance must be checked, since the reabsorption of urine can lead to acidosis ; If necessary, treatment of acidosis with bicarbonate is indicated.

The simplest form of urinary diversion is the ureteral skin fistula. The ureters are sewn directly into the skin. The advantage is that the bladder removal is less stressful because the peritoneum does not have to be opened. The disadvantage is the permanent splinting of the ureters with regular splint changes.

In the 1950s, US surgeons developed the drainage of urine via the intestine and worked out the method of forming a neo-bladder from parts of the intestine.

forecast

The prospect of a cure depends very much on the extent of the tumor at the start of treatment. Stage T1 patients have a 5-year survival rate of around 80%. In stage T2 this falls to around 60%, in stage T3 it is 30–50%. Of the patients in whom a T4 tumor is detected, only 20% are still alive after 5 years, despite optimal therapy. Other factors for a poor prognosis are lymph node metastases, infiltration of the urethra, multiple tumor locations within the bladder and a tumor size over three centimeters.

Occupational disease

In 1895, the German surgeon Ludwig Rehn established the connection between activities in the aniline processing industry and the development of bladder cancer. Bladder cancer is one of the recognized occupational diseases with the appropriate constellation. The Hessian State Social Court in Darmstadt decided in 2019 that a car mechanic - when he was 38 years old, was diagnosed with a bladder tumor according to BK No. 1301 - had an occupational disease for which the trade association has to compensate financially. Long-term contact with toxic lead compounds in petrol was fundamental to his illness. In addition, the man was a non-smoker; Tobacco consumption usually has a harmful effect on bladder tumors. (Az. L 3 U 48/13) The court did not allow an appeal.

Economic aspects

The average cost of treating a patient with bladder cancer in the United States ranged from $ 96,000 to $ 187,000 . In 2001, a total of $ 3.7 billion was spent on diagnosis and treatment of this cancer in the United States.

literature

- R. Hautmann, H. Huland: Urology. 3rd, revised. Edition. Springer, Heidelberg et al. 2006, ISBN 3-540-29923-8 .

- R. Rubin, D. Strayer et al: Rubin's Pathology. 5th edition. Kluwer, Philadelphia 2008, ISBN 978-0-7817-9516-6 . (English)

- JA Efstathiou et al .: Bladder sparing approaches to invasive disease. In: World J Urol. 24, 2006, pp. 517-529.

- C. Weiss et al: Radiochemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil after transurethral surgery in patients with bladder cancer. In: Int J radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 68, 2007, pp. 1072-1080.

Web links

- Bladder carcinoma chapter from the online urology textbook for doctors and healthcare professionals

- K. Golka among others: Etiology and prevention of bladder carcinoma. Part 1 of the series on bladder cancer In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 104, issue 11 of March 16, 2007, p. A-719.

- Treatment recommendation for bladder carcinoma. University Hospital Essen, accessed on February 1, 2016 .

- First S3 guideline on bladder cancer published. Deutsches Ärzteblatt , Oncology Guideline Program , October 4, 2016, accessed on October 17, 2016 .

- S3 - Guideline for bladder carcinoma - early detection, diagnosis and therapy of the various stages of the German Society for Urology eV (DGU) and the German Cancer Society (DKG) -> AWMF registration number: 032-038OL (registration date: April 16, 2013); Planned completion: February 28, 2017. In: AWMF online

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dieter Jocham, Andreas Böhle: Systematic chemotherapy for urothelial carcinoma. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 1996, accessed on October 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Hartwig Huland, MG Friedrich: Urinary bladder carcinoma. In: Richard Hautmann, Hartwig Huland: Urology. 3. Edition. Heidelberg 2006, pp. 202-212.

- ↑ a b Cancer - Cancer in Germany 2013/2014 - frequencies and trends. (PDF) A joint publication by the Robert Koch Institute and the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany. V. , accessed on October 10, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Ivan Damyanov: The Lower Urinary Tract and Male Reproductive System. In: R. Rubin, D. Strayer et al .: Rubin's Pathology. 5th edition. Philadelphia 2008, pp. 752-758.

- ↑ a b c d e f g J. N. Eble, G. Sauter, JI Epstein, IA Sesterkenn (Ed.): World Health Organization Classification of Tumors- Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon 2004, pp. 90-108.

- ↑ Montserrat García-Closas et al .: NAT2 slow acetylation, GSTM1 null genotype, and risk of bladder cancer: results from the Spanish Bladder Cancer Study and meta-analyzes . In: Lancet (London, England) . tape 366 , no. 9486 , August 2005, p. 649-659 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (05) 67137-1 , PMID 16112301 , PMC 1459966 (free full text).

- ↑ AM Nieder, S. John, CR Messina, IA Granek, HL Adler: Are patients aware of the association between smoking and bladder cancer? In: J Urol . 176, 2006, pp. 2405-2408. PMID 17085114 .

- ↑ P. Aveyard et al .: Does smoking status influence the prognosis of bladder cancer? A systematic review . In: BJU international . tape 90 , no. 3 , August 2002, p. 228-239 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1464-410x.2002.02880.x , PMID 12133057 .

- ↑ rme / aerzteblatt.de: Smoking explains half of all bladder cancers . (No longer available online.) In: aerzteblatt.de . August 17, 2011, archived from the original on April 24, 2015 ; accessed on February 2, 2015 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Klaus Golka et al .: Etiology and prevention of bladder carcinoma. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. March 16, 2007, accessed April 4, 2020 .

- ↑ D. Schmähl: Iatrogenic carcinogenesis . In: Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology . tape 99 , no. 1-2 , 1981, pp. 71-75 , doi : 10.1007 / bf00412444 , PMID 7251640 .

- ↑ FDA Safety Alerts: FDA Drug Safety Communication: Update to ongoing safety review of Actos (pioglitazone) and increased risk of bladder cancer .

- ↑ FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated FDA review concludes that use of type 2 diabetes medicine pioglitazone may be linked to an increased risk of bladder cancer. FDA, December 12, 2016, accessed October 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Deutsches Ärzteblatt: Pioglitazon: FDA is examining possible bladder cancer risk . ( Memento of the original from December 3, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 20th September 2010.

- ↑ Pioglitazone: Study confirms bladder cancer risk. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. August 14, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2017 .

- ^ MR Weihrauch and V. Diehl: Artificial sweeteners - do they bear a carcinogenic risk? In: Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology . tape 15 , no. 10 , October 2004, p. 1460-1465 , doi : 10.1093 / annonc / mdh256 , PMID 15367404 .

- ↑ Cristina M. Villanueva et al .: Bladder cancer and exposure to water disinfection by-products through ingestion, bathing, showering, and swimming in pools . In: American Journal of Epidemiology . tape 165 , no. 2 , January 15, 2007, p. 148-156 , doi : 10.1093 / aje / kwj364 , PMID 17079692 .

- ↑ Maurice PA Zeegers et al .: The association between smoking, beverage consumption, diet and bladder cancer: a systematic literature review . In: World Journal of Urology . tape 21 , no. 6 , February 2004, p. 392-401 , doi : 10.1007 / s00345-003-0382-8 , PMID 14685762 .

- ↑ Urine liquid biopsies could help monitor bladder cancer treatment , September 26, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ↑ Ashley Di Meo et al .: Liquid biopsy: a step forward towards precision medicine in urologic malignancies . In: Molecular Cancer . tape 16 , no. 1 , April 14, 2017, p. 80 , doi : 10.1186 / s12943-017-0644-5 , PMID 28410618 , PMC 5391592 (free full text).

- ↑ H. Barton Grossman et al .: Detection of bladder cancer using a point-of-care proteomic assay . In: JAMA . tape 293 , no. 7 , February 16, 2005, p. 810-816 , doi : 10.1001 / jama.293.7.810 , PMID 15713770 .

- ↑ IGeL-Monitor, Assessment of the NMP22 test for the early detection of bladder cancer , accessed October 8, 2018.

- ^ ER Ray, K. Chatterton, MS Khan, K. Thomas, A. Chandra, TS O'Brien: Hexylaminolaevulinate 'blue light' fluorescence cystoscopy in the investigation of clinically unconfirmed positive urine cytology. In: BJU Int. 103 (10), May 2009, pp. 1363-1367. PMID 19076151 .

- ↑ a b G. Jakse, M. Stöckle, J. Lehmann, T. Otto, S. Krege, H. Rübben: Metastatic urinary bladder carcinoma. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . Vol. 104, issue 15, April 13, 2007, pp. 1024-1028.

- ↑ a b c K. Lindemann-Docter, R. Knüchel-Clarke: Histopathology of the urinary bladder carcinoma. In: The Urologist. 47, 2008, pp. 627-638.

- ^ Bladder Cancer Staging | Bladder Cancer Stages. Accessed October 10, 2018 .

- ↑ a b W. Böcker, H. Denk, Ph. U. Heitz, H. Moch: Pathology. 4th edition. Munich 2008, pp. 893-896.

- ↑ K. Lindemann-Docter et al .: The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma . In: The Pathologist . tape 29 , no. 5 , September 1, 2008, ISSN 1432-1963 , p. 383-387 , doi : 10.1007 / s00292-008-1018-y .

- ^ R. Moll et al .: Uroplakins, specific membrane proteins of urothelial umbrella cells, as histological markers of metastatic transitional cell carcinomas . In: The American Journal of Pathology . tape 147 , no. 5 , November 1995, pp. 1383-1397 , PMID 7485401 , PMC 1869506 (free full text).

- ↑ K. Mellon et al .: Cell cycling in bladder carcinoma determined by monoclonal antibody Ki67 . In: British Journal of Urology . tape 66 , no. 3 , September 1990, pp. 281-285 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1464-410x.1990.tb14927.x , PMID 2207543 .

- ↑ AS Sarkis et al .: Nuclear overexpression of p53 protein in transitional cell bladder carcinoma: a marker for disease progression . In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute . tape 85 , no. 1 , January 6, 1993, p. 53-59 , doi : 10.1093 / jnci / 85.1.53 , PMID 7677935 .

- ↑ Marc Decobert et al .: Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin in high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: how much is enough? In: Cancer . tape 113 , no. 4 , August 15, 2008, p. 710-716 , doi : 10.1002 / cncr.23627 , PMID 18543328 .

- ↑ Alexandre R. Zlotta et al .: The management of BCG failure in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an update . In: Canadian Urological Association Journal . tape 3 , 6 Suppl 4, December 2009, p. S199-S205 , PMID 20019985 , PMC 2792453 (free full text).

- ↑ M. Babjuk (chair), A. Böhle, M. Burger, E. Compérat, E. Kaasinen, J. Palou, BWG van Rhijn, M. Rouprêt, S. Shariat, R. Sylvester, R. Zigeuner: EAU Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1 and CIS) ( Memento from July 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) 2014.

- ↑ Raymond H. Mak et al .: Long-term outcomes in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer after selective bladder-preserving combined-modality therapy: a pooled analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocols 8802, 8903, 9506, 9706, 9906, and 0233 . In: Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology . tape 32 , no. 34 , December 1, 2014, p. 3801–3809 , doi : 10.1200 / JCO.2014.57.5548 , PMID 25366678 , PMC 4239302 (free full text).

- ↑ FW Klinge and EM Bricker: The evacuation of urine by ileal segments in man . In: Annals of Surgery . tape 137 , no. 1 , January 1953, p. 36-40 , doi : 10.1097 / 00000658-195301000-00005 , PMID 12996965 , PMC 1802393 (free full text).

- ^ EM Bricker: Substitution for the urinary bladder by the use of isolated ileal segments . In: The Surgical Clinics of North America . August 1956, p. 1117–1130 , doi : 10.1016 / s0039-6109 (16) 34949-0 , PMID 13371525 .

- ↑ https://sozialgerichtsbarkeit.hessen.de/pressemitteilungen/berufsgenossenschaft-muss-blasenkrebs-eines-kfz-mechanikers-als-berufskrankheit

- ↑ M. Botteman, CL Pashos, A. Redaelli, B. Laskin, R. Hauser: The Health Economics of Bladder Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of the Published Literature. In: Pharmacoeconomics . 22 (18), 2003, pp. 1315-1330.