Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat ([ basˈkja ] born December 22, 1960 in New York City , † August 12, 1988 ibid) was an American artist, painter and draftsman. He was the first African American artist to break through in the mostly white art world. Basquiat contradicted the usual classification as a graffiti artist: “I am not part of graffiti art.” To this day, he polarizes when determining his position in art history. In order to understand his pictures, writes the essayist bell hooks , one must be ready to accept the tragic dimension of a black life; she refers to James Baldwin's essay The Fire Next Time (1963), “that there is no language for the horrors of black life.” Basquiat's work gives this horror an artistic expression.

Life

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born a year after the death of his brother Max (1959), the second son of Matilda Basquiat, whose family came from Puerto Rico , and Gerard Basquiat, who had left Haiti in the 1950s . At the age of four he learned to read and write. His mother, who was interested in art, who painted and drew herself, visited the Brooklyn Museum with him , for which he received an annual ticket. His family belonged to the rising middle class and could afford to send their son to a Catholic private school. In 1968, Matilda Basquiat separated from her husband and children. Jean-Michel had no friends; mostly he played with children who also had no friends. At the age of eleven he spoke perfect French and Spanish in addition to American English. When his mentally ill mother visited her children, she would sit with them on the steps in front of the house. From 1974 to 1976 he lived in Puerto Rico with his sisters and father. Back in Brooklyn, he ran away from home for a few days after problems with his father. He came to City As School for talented teenagers with problems. The students are given special support there. In 1977 Basquiat ran away from home again.

From April 1979 he played clarinet and synthesizer in the noise band Gray, which appeared in clubs such as Max's Kansas City , CBGB , Hurray at the Mudd Club , and at Arleen Schloss . From 1979 Basquiat was together with Walter Steding , Debbie Harry , Chris Stein and Klaus Nomi a regular "TV Party" guest, a weekly underground punk rock show with Glenn O'Brien , the music critic of the magazine Interview by Andy Warhol . He met Andy Warhol through Glenn O'Brien. Until 1981 he lived alternately with friends in Soho, before he was able to buy his first apartment in 1982 by selling pictures. He lived there with his partner Susanne Mallouk. He painted daily in the basement of the gallery of Anina Nossei, his gallery owner. There he produced pictures at a breathtaking pace, some of which were sold before completion. In 1982, at the age of 21, he was still the youngest participant in a documenta ( documenta 7 ). In 1983 he rented a house on Great Jones Street from Andy Warhol, where he lived and worked. Exhibitions in museums and galleries around the world made his work more and more popular. In 1984 he moved to the Mary Boone Gallery, one of the most prestigious galleries in New York. "I wanted to be in a gallery with older artists," says Basquiat. According to McGuigan, however, he wanted above all to end art critics' defamatory comparisons with graffiti and become an "established" artist, because, according to Fred Braithwaite aka Fab 5 Freddy : "Graffiti had become another word for nigger."

Basquiat ended the collaboration with the Mary Boone Gallery in 1986. He traveled to Germany, where he had a solo exhibition in the Hanoverian Kestner Society . In Hamburg he worked with Salvador Dalí , Keith Haring , Joseph Beuys and others on the equipment for André Heller's Luna Luna , an avant-garde amusement park. When Andy Warhol died in February 1987, Basquiat fell into a serious crisis. From June 1987 the New York art dealer Vrej Baghoomian was his gallery owner, but Basquiat did not exhibit for over a year. In 1988 Basquiat showed his last pictures in the gallery Vrej Baghoomian, in which he made death the subject of reference to death through the repeated words MAN DIES in the “Eroica” pictures and the picture “Riding with Death”.

With the artist Ouattara Watts , whom he had met in Paris at the beginning of 1988, Basquiat planned to fly to Abidjan , Ivory Coast , in his homeland on August 19, 1988 . There shamans should rid him of his drug addiction. The plane tickets remained unused; on August 12, 1988 he died of an overdose. He left behind more than 1000 paintings and objects as well as 2000 drawings. In one of his last notebooks he noted that he wanted to buy a saxophone.

“When he died, it was immediately clear to me which scenario had to be used to get him under control with explanations: too much in too short a time, an indisciplinary greed for life. It is the nature of the media beast to simplify the complex so that it is distorted beyond recognition. "

SAMO ©

Together with his school friend Al Diaz, he wrote poetic and often critical phrases on the walls of houses in the Soho gallery district from 1977 on, such as “SAMO © as an end to playing art”, “SAMO © as an end to mindwash religion, stop running around with the radical chic playing art with daddy's dollars ”, which he signed with the pseudonym SAMO ©. SAMO © is an abbreviation for “same old shit”, which in Afro-American colloquial language stands for the unchanged racist conditions in the United States. The secret SAMO © messages moved the New York art scene, which had been puzzling for over a year as to who could be behind the messages with the pseudonym SAMO ©. One suspected a white representative of Conceptual Art, explained the rapper Fab 5 Freddy in Interview magazine. Basquiat and Diaz made sure to put their graffiti where it could be seen by lovers of the latest art. Basquiat's early Samo graffiti can rather be described as a kind of “anti-graffiti” to the existing New York graffiti, he wrote in a deliberately unaffected style that was characterized by an ironic, educated and refined observation of reality. The secret of SAMO © was revealed in December 1978 by the town magazine Village Voice with the article "The SAMO Graffiti .. Boosh Wah or CIA?"

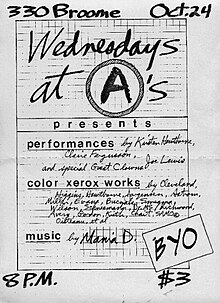

In January 1979 Basquiat and Al Diaz separated, Basquiat exhibited XEROX work at Arleen Schloss on October 24, 1979 under his pseudonym SAMO © . The lettering “Samo © as a neo art form” is considered to be the hour of birth of conceptual graffiti art. The copyright symbol © was a game between brands and commerce; so Basquiat wanted to provoke the Soho art scene. The art historian Catherine Hug ( Kunsthalle Wien ) sees Samos' graffiti aphorisms as interventions that were staged like a political conspiracy campaign. “SAMO” was the title of his first exhibition in Europe, at the Mazolli Gallery in Modena in 1981. The art historian Dieter Buchhart sees a final erasure of the pseudonym in the 1981 painting “Cadillac Moon”, in which “Samo ©” crossed out and “Jean-Michel Basquiat ”is set against it. The "samo-isms" have disappeared from the New York cityscape. In 1979 Basquiat wrote a "Samo-ism" in a saxophonist's case, which has been preserved to this day. Henry Flynt, American philosopher and artist, photographed the secret messages in the late 1970s and saved them for posterity.

Art historical classification

Basquiat's gestural and direct way of working has often led to his painting being referred to as Neo-Expressionism. The layer structure of the paintings, their surface damage, the collaboration with Andy Warhol, the sampling of his own earlier ideas and the interplay of radical emptiness and horror vacui stand against it. His pictures are partly reminiscent of black African folk art, partly of a hodgepodge of street and consumer culture in North American cities. The materials and techniques that he used are equally diverse. He could use anything to produce pictures. He used words, signs and pictograms he found in his work, which he called "facts". “I get my facts from books. Stuff about atomizers, the blues, methyl alcohol, Egyptian style geese. I get my suggestions from books. What I like appears in my pictures. I do not take responsibility for my facts. You exist without me. A menu in a restaurant is a picture. Maybe I won't eat the roast pork, but its image lives on. The menu, the writing, they continue to exist without me ”. Combining various imaging elements is an integral part of Basquiat's art. His images are usually covered in words, letters, numbers, pictograms, logos, symbols, cards, graphics and more.

Voices about the work

- Keith Haring : “It had content to offer, but that was not the only thing that stood out from the graffiti scene. He did not write on subway cars, but on the walls of houses, wherever his forays led him. And mostly they took him to SoHo, where the galleries were and where his peers and soulmates lived and hung around ”.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat about himself: “My work has nothing to do with graffiti, most people are just racists ... and they talk about graffiti endlessly, even though I don't consider myself a graffiti artist. They have this picture of me: the savage on the run, the savage ape man or whatever the hell they think, ”in an interview with Tamra Davis in 1986.

- Susanne Reichling: Basquiat did not see himself as a painter, but as a “writer” of lists, tables and “vocabulary books”. The hasty but popular classification of Basquiat in the context of painting of the eighties as a graffiti artist or neo-expressionist misjudges the diversity and meaning of his works.

Characters

In Basquiat's work, writing has a central role that is on an equal footing with elements, color and figuration. He makes use of a certain canon of signs and shapes that keep appearing, such as the trademark (TM) and copyright (©) and hobo (tramp) symbols. He crosses out words to draw attention to them. With his integration of writing into the picture, Basquiat ties in with the tradition of Dadaism , Futurism and analytical Cubism . He integrates hip-hop texts into his pictures that have no syntactic connection. Just like Anselm Kiefer , who inserts writing into his paintings "in order to connect them to historical, mythological or literary contexts", Basquiat also uses writing to refer to "things, events and conditions inside and outside the pictorial space". The writing in his works is mostly in English, occasionally also in German, French and Spanish.

Collaboration Warhol, Basquiat, Clemente

In 1983, the gallery owner Bruno Bischofberger suggested a collaboration between the artists he represented. Andy Warhol, as a representative of Pop Art , brought graphic and serial elements into the collaboration in a clear, often cool-looking style. The spirited opposite pole came from Jean-Michel Basquiat with an angry expressive gesture, a mixture of symbols, pictograms and letters. The dreamlike, mystical, almost surreal parts in the joint work come from Francesco Clemente , a representative of the Transavanguardia . The "Collaboration" shows the basic idea of Pop Art - namely to replace abstract art with trivialized, objective content, to establish the banality of everyday life, the consumer and advertising world in the visual arts.

reception

The New York critics' camp was divided into the euphoric (left) supporters and the mostly conservative enemies of Basquiat. The African-American feminist bell hooks took in her essay “Altars of Sacrifice. Remembering Basquiat “1993 position on the Basquiat retrospective at the Whitney Museum from 1992 and criticized above all the misunderstood reception of Basquiat among white art critics. Because he is black and young, some critics won't be able to resist associating Basquiat with the more obvious forms of black or Puerto Rican street art in New York.

Renowned white art critics such as Hilton Kramer and Robert Hughes see in Basquiat a little talented artist, a graffiti artist who has been “cheered” upwards by the New York art scene, Hilton Kramer ( New York Times ) stated in a 1985 film interview: “Basquiat's importance is so small that it is practically zero ”. After Basquiat's death, Robert Hughes wrote the article “Jean-Michel Basquiat. Requiem for a featherweight "(Requiem for a featherweight). Basquiat's first major retrospective at the Whitney Museum, New York in 1992, was what Hilton Kramer called “A Disaster”. Robert Hughes wrote "Life was so sad and short and the art that came out of it so limited makes it unfair to go into it". Rammellzee , New York Hip-Hop Musician and Artist "We were called graffiti artists, but he wasn't".

Through his life and work, Jean-Michel Basquiat embodied the synthesis of African, Caribbean, Afro-American, white American and European cultures. Appropriate study of his work moves between situating his life and work within the New York subculture of the early eighties and an "academic" reading of his pictorial content, as Greg Tate states in his 1992 catalog essay "Black Like B.": “Basquiat was… a populist postmodernist. He belongs to a black tradition, well established by our musicians, of making work that is heady enough to confound academics and hip enough to capture the attention span of the hip-hop nation. "

Art market

Basquiat's works are among the most sought-after art objects of the 20th century. In 2008, his 1982 work Untitled (Boxer) was sold to an unknown person at an auction in New York by the Christie’s auction house for around 13.5 million US dollars. The previous owner was Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich . One of the highest prices for a Basquiat work is $ 14.6 million for his Untitled (Pecho / Oreja) , which was put up for auction by the rock band U2 in 2007 . A nameless self-portrait, created in Italy in 1982, was auctioned in May 2016 at Christie's auction house for $ 57.3 million (50.37 million euros) to an anonymous Asian collector, which at the time meant a record price for a work by Basquiat. On May 18, 2017, a work by Basquiat was auctioned at Sotheby's for the new record price of 110.5 million dollars (99.4 million euros). The picture "Untitled" went to the Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa . It is the first painting since 1980 that retailed for more than $ 100 million.

Johnny Depp , Dave Stewart (Eurythmics), Dennis Hopper , John McEnroe , Madonna and Leonardo DiCaprio are among others. a. to the collectors of his works. Most of his best work is in the hands of a few collectors such as Peter Brant , Eli Broad , Philippe Niarchos, Dennis Scholl and the Mugrabi family of collectors, who own a great many works. Alberto "Tico" Mugrabi (1970) had the Basquiat crown tattooed on his wrist.

From June 1988 until his death, Basquiat worked with the German entrepreneur and artist Helmut Diez to develop a concept for an Association of Painters whose object was to sponsor young artists by world-famous ones.

Fakes

Vrej Baghomian, Basquiat's last art dealer, sold several Basquiat paintings to the dealer Daniel Templon in 1994 , which the latter exhibited at the FIAC art fair in Paris. A visitor to the fair discovered that these pictures could not be from Basquiat. The Basquiat Authorization Committee with Gerard Basquiat, John Cheim, Jeffrey Deitch, Larry Warsh, Diego Cortez and Richard Marshall confirmed this. Image titles such as "Smoke Bomb, Tax-Free, Balloon, Mass Slums and Ascecticism" did not correspond to the artist's choice of words.

Filmography

- Basquiat played the leading role in the film New York Beat . He did not see the film, which was published in 2010 under the title Downtown 81 , "they always kept me away from looking through the filmed footage".

- In the Blondie video clip "Rapture", Basquiat played a disc jockey who, by wearing Bavarian country fashion, forms an optical antithesis to Debbie Harry .

various

- The poet Kevin Young dedicated a compendium of 117 poems in 1991 to To Repel Ghosts , Basquiat.

- The poet MK Asante dedicated the poem "SAMO" in his book Beautiful to Basquiat in 2005 . And Ugly Too .

- Julian Schnabel made a film about the artist called Basquiat (1996).

- Jazz bassist Lisle Ellis wrote the Sucker Punch Requiem - An Homage to Jean-Michel Basquiat in 2007 .

- In 2010 Tamra Davis produced a documentary on Basquiat called The Radiant Child .

- The documentary Jean-Michel Basquiat - Portrait of the Graffiti Artist was shown by Jean-Michel Vecchiet on Swiss TV SRF in 2013 .

- In 2017 BBC Two showed the documentary Basquiat - Rage to Riches by David Shulman.

Retrospectives

In October 1992 to February 1993 the Whitney Museum of American Art showed the first "Jean-Michel Basquiat" retrospective, which was then exhibited in Texas , Iowa and Alabama . The catalog for this exhibition by Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat , Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992 (out of print) offers a differentiated view of Basquiat's working method and style and is considered a relevant source. In 2005, from March – June , the Brooklyn Museum showed Basquiat, an exhibition that later went to Los Angeles and Houston.

The Fondation Beyeler in Riehen near Basel , Switzerland , showed a Basquiat retrospective in 2010, which had almost 110,000 visitors. The exhibition then moved to the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris, where more than 200,000 visitors saw the exhibition.

The Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt showed the first Basquiat retrospective in Germany from February to May 2018.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1980 SAMO ©, Arleen Castle , New York

- 1980 Times Square Show

- 1981 New York – New Wave, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Long Island City, Queens / New York

- 1981 Galleria Emilio Mazzoli, Modena

- 1981 Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

- 1982 Larry Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles

- 1982 documenta 7, Kassel

- 1982 Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

- 1982 Marlborough Gallery, New York

- 1982 Bruno Bischofberger Gallery, Zurich

- 1982 Fun Gallery, New York

- 1982 New New York, Florida-State University Art Gallery, Tallaliasse, Florida

- 1982 Metropolitan Museum & Art Center, Coral Gables, Florida

- 1982 Body Language - Current Issues in Figuration, University Art Gallery, San Diego State University, San Diego, California

- 1982 Avanguardia e Transavanguardia '68 - '77, Rome

- 1982 Cinque Americani, Museo Civico, Modena

- 1982 Drawings / Visions, New York, Janus Gallery, Los Angeles

- 1982 Works on Paper, Larry Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles

- 1982 The Pressure to Point, Marlborough Gallery, New York

- 1982 Transavanguardia Italia - America, Galleria Cicica, Modena

- 1982 Still Modern After All These Years, Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia

- 1982 New York Now, Kestnergesellschaft Hannover

- 1983 Larry Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles

- 1983 Bruno Bischofberger Gallery, Zurich

- 1983 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Tokyo

- 1983 West Beach Café, Venice, Californie

- 1983 New York Now, Kunstverein Munich ; Musée cantonal des beaux-arts de Lausanne ; Art Association for the Rhineland and Westphalia Düsseldorf

- 1983 Whitney Biennale, Whitney Museum of American Art , New York

- 1983 Back to the USA, Kunstmuseum Luzern

- 1983 Artists, The Seibu Museum of Art, Tokyo

- 1983 Written Imagery Unleashed in the Twentieth Century, Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, Long Island / New York

- 1983 From the Streets, Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, South Carolina

- 1983 Paintings, Mary Boone Gallery, New York

- 1984 Mary Boone Gallery, New York

- 1984 The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

- 1984 Institute of Contemporary Arts London

- 1984 Painting and Sculpture Today, Indianapolis Museum of Art , Indianapolis, Indiana

- 1984 American Neo-Expressionists, Aldri Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, Connecticut

- 1984 New Art, Musée d'Art Contemporain, Montréal

- 1984 Free Figuration France / USA Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris

- 1985 Bruno Bischofberger Gallery, Zurich

- 1985 Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum Rotterdam

- 1985 Mary Boone / Michael Werner Gallery, New York

- 1985 XIII BIENNALE DE PARIS - Biennale de Paris, Paris

- 1986 Larry Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles

- 1986 Bruno Bischofberger Gallery, Zurich (drawings)

- 1986 Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery , Salzburg

- 1986 Center Culturel Français, Abidjan, Ivory Coast

- 1986 Kestnergesellschaft , Hanover

- 1986 Michael Werner Gallery, Cologne

- 1987 Daniel Templon , Paris

- 1987 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Tokyo

- 1988 Hans Mayer Gallery, Düsseldorf

- 1988 Vrej Baghoomian, Inc., New York

- 1988 Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

- 1989 Paintings Drawings, Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, Salzburg

- 1992 Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective, New York

- 1994 The Theater of Refusal: Black Art & Mainstream Criticism - Center for Art and Visual Culture, Baltimore, MD

- 1996 23 ° Bienal de São Paulo - Bienal de Sao Paulo, São Paulo

- 1996 Collaborations - Warhol, Basquiat, Clemente - Kunsthalle Fridericianum , Kassel

- 1998 Poèmes à petite vitesse - Musée d'Art Contemporain Lyon, Lyon

- 1999 The American Century - Art & Culture 1900–2000 Part II - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

- 2000 Around 1984 - A Look at Art in the Eighties - MoMA PS1, New York City, NY

- 2000 Painting the Century: 101 Portrait Masterpieces 1900–2000 National Portrait Gallery , London

- 2001 One Planet Under a Grove: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art - Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York City, NY

- 2003 American Figures. Between Pop Art and Trans-Avantgarde - Stella Art Foundation, Moscow

- 2003 50th International Art Exhibition Venice Biennale / Biennale di Venezia - La Biennale di Venezia, Venice

- 2005 Beautiful Losers - Contemporary Art and Street Culture - University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, Tampa, FL

- 2005 Basquiat - Brooklyn Museum

- 2005 El foc davall de les cendres (de Picasso a Basquiat) - Institut Valencià d'Art Modern , Valencia

- 2005 De Picasso a Basquiat - Musée Maillol - Fondation Dina Vierny, Paris

- 2005 BIG BANG - Center Georges Pompidou - Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- 2005 my private Heroes - MARTa Herford

- 2006 Basquiat - una antología para Puerto Rico - Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, Santurce

- 2006 Basquiat 1960–1988 - Basquiat Retrospective - Shanghai Duolun Museum of Modern Art, Shanghai

- 2006 Radical NY! The Downtown show: the New York art scene, 1974-1984 and abstract expresionism: 1940-1960 - Austin Museum of Art - AMOA, Austin, TX

- 2006 THE 1980s - A TOPOLOGY - Museu Serralves - Museu de Arte Contemporânea , Porto

- 2006 The Downtown Show: The New York Art Scene, 1974–1984 - The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburg, PA

- 2006 Sound & Vision - Museo della Città, Perugia

- 2007 Schönwahnsinnig - Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation - Gottorf Castle, Schleswig

- 2007 Crossing Currents - The Synergy of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Ouattara Watts - Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, NH

- 2007 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Works on Paper - Van de Weghe Fine Art, New York City, NY

- 2007 Basquiat in Cotonou - Fondation Zinsou, Cotonou

- 2007 POP ART 1960's to 2000's - Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima

- 2007 From Klimt to Krystufek - Museum der Moderne Salzburg , Rupertinum

- 2007 Panic Attack! - Art in the Punk Years - Barbican Center , London

- 2012 Ménage à trois - Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany , Bonn

- 2012 Meneer Delta - Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen , Rotterdam

- 2012 God Save the Queen: Punk in the Netherlands 1977–1984 - Centraal Museum, Utrecht

- 2013 Warhol / Basquiat - Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien , Vienna

- 2015 NOW'S THE TIME - Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao

- 2017/2018 Boom for Real - Barbican Center , London, and Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt am Main

- 2018/2019 Schiele / Basquiat - Fondation Louis Vuitton , Paris

- 2019 Basquiat - The Artist and his New York Scene - Museum im Glaspalast Schunck, Heerlen

literature

- Doris Berger: Projected Art History Transcript; Edition: 1st edition (February 2009) ISBN 978-3-8376-1082-6

- Dieter Buchhart, Glenn O'Brien, Jean-Louis Prat, Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat , Hatje Cantz, 2010. ISBN 978-3-7757-2593-4

- Jennifer Clement : Widow Basquiat. A love story . Payback Press, Edinburgh 2000, revised edition 2014.

- Mallory Curley: A Cookie Mueller Encyclopedia , Randy Press, 2010.

- J. Deitch, D. Cortez, Glenn O'Brien: Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1981: the Studio of the Street , Charter, 2007. ISBN 978-88-8158-625-7

- Leonhard Emmerling: Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960–1988 . Taschen, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-8228-1636-1

- Sam Keller (Ed.): Basquiat . Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective. Hatje Cantz Publishing House . ISBN 978-3-7757-2592-7

- Eric Fretz: Jean-Michel Basquiat: a biography , Santa Barbara, Calif. [u. a.]: Greenwood, 2010, ISBN 978-0-313-38056-3

- Phoebe Hoban: Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (2nd edition), Penguin Books, 2004.

- Luca Marenzi: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Charter, 1999. ISBN 978-88-8158-239-6

- Richard Marshall: Jean-Michel Basquiat , Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art. Hardcover 1992, paperback 1995 (Catalog for 1992 Whitney retrospective, out of print).

- Richard Marshall: Jean-Michel Basquiat: In World Only. Cheim & Read, 2005 (out of print).

- Marc Mayer, Fred Hoffman et al .: Basquiat , Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. The Afro-American context of his work . Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1999.

- Greg Tate: Flyboy in the Buttermilk . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 978-0-671-72965-3

Web links

- Literature by and about Jean-Michel Basquiat in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Jean-Michel Basquiat in the German Digital Library

- Materials by and about Jean-Michel Basquiat in the documenta archive

- Jean-Michel Basquiat on kunstaspekte.de

- Information about Basquiat on artcyclopedia (with information about the locations of his pictures)

- Basquiat.com Official site of The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sam Keller (ed.): Basquiat . Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective, Hatje Cantz Verlag, p. XXIX

- ↑ Sam Keller (ed.): Basquiat . Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective, Hatje Cantz Verlag, article by the art historian Dieter Buchhart, p. X

- ↑ bell hooks: "Altars of Sacrifice: Remembering Basquiat". Art In America. June 1993, pp. 68-75.

- ↑ Biography ( Memento from July 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file)

- ^ Jean-Michel Basquiat and National Heroes. February 4, 2009, accessed January 13, 2015 . In: famz.deviantart.com

- ↑ Sam Keller (ed.): Basquiat . Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective, Hatje Cantz Verlag, p. XXIII

- ^ Basquiat at Houston & # 039; s Museum of Fine Arts. In: artinfo.com. September 11, 2007, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ A's * A’s , In: Bowery Artist Tribute NEW MUSEUM, Editor Ethan Swan, New York 2010.

- ^ Cathleen McGuigan: New Art, New Money - The Marketing of an American Artist. The New York Times Magazine. February 10, 1985, pp. 20–28, 32–35, 74 (title report)

- ^ Anthony Haden-Guest: Burning Out. In: Vanity Fair. Vol. 51, No. 11, November 1988.

- ^ Kestner Society, Hanover: Jean-Michel Basquiat. November 28, 1986 - January 25, 1987.

- ↑ Franklin Sirmans In: Marshall, Richard (Ed.): Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art 1992. p. 248.

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban: Hyped to Death by The New York Times (August 9, 1998). In: New York Magazine. dated Sept. 26, 1988, ISSN 0028-7369 , Volume 21, No. 38, p. 36 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban: Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (2nd edition), Penguin Books, 2004, Preface S. x

- ↑ Kieth Haring: Remembering Basquiat In: Vogue. November 1988, pp. 230-234.

- ↑ Ingrid Sischy: Jean-Michel Basquiat as told by Fred Braithwaite aka Fab 5 Freddy. Interview. October 1992, 119-123.

- ↑ Interview Magazin 10 / XXII, October 1992, page 119.

- ^ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Hamburg 1998, p. 37.

- ↑ Philip Faflick: The SAMO Graffiti .. Boosh Wah or CIA? , Village Voice December 11, 1978.

- ↑ SAMO ESTA EN ALGO, a young man is in the suitcase. In: evaresken.de. September 10, 2014, archived from the original on April 26, 2012 ; accessed on January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ a b This is not a suitcase, it just looks like it. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung of March 27, 2011. p. 31.

- ↑ The SAMO © Graffiti photographed by Henry Flynt. In: henryflynt.org. Retrieved January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Dieter Buchhart, Glenn O'Brien, Jean-Louis Prat, Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat , Hatje Cantz, 2010.

- ↑ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Afro-American Context of His Work Dissertation, University of Hamburg, 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Basquiat, In: Carl Haenlein (Ed.): Jean-Michel Basquiat. Exhibition catalog, Hanover 1987, p. 23.

- ^ John Berger : Seeing Through Lies: Jean-Michael Basquiat . In: Harper's Foundation (ed.): Harper’s . 322, No. 1,931, 2011, pp. 45-50. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ Tamra Davis: Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child. Independent Lens. PBS. October 25, 2011.

- ^ Kieth Haring: Remembering Basquiat. In: Vogue November 1988, pp. 230-234.

- ↑ Sam Keller (ed.): Basquiat. Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective, Hatje Cantz Verlag, p. XXVI.

- ^ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. The Afro-American context of his work. Dissertation, University of Hamburg, 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ Dominique Selzer: Legible characters in painting of the 20th century. Heidelberg, 2001, pp. 216-218.

- ^ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Hamburg 1998, p. 37, p. 36.

- ^ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. The Afro-American context of his work. Dissertation, University of Hamburg, 1999, p. 36.

- ↑ accessed on March 21, 2012 Westzeit - GERMAN POP. In: westzeit.de. November 1, 2014, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ^ Warhol, Basquiat, Clemente in the Bundeskunsthalle In: welt.de

- ^ Susanne Reichling: Jean-Michel Basquiat. The Afro-American context of his work. Dissertation, University of Hamburg, 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ bell hooks: Altars of Sacrifice: Remembering Basquiat. In: Art In America. June 1993, pp. 68-75.

- ^ Robert Farris Thompson: Activating Haeven: The Incantatory Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Exhibition catalog Mary Boone Michael Werner Gallery, New York. 1985.

- ↑ 'Radical Chic' - Still Alive And Well. In: articles.nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012 ; accessed on January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ The Radiant Child , film by Tamara Davies, 2010.

- ^ The new Republic , Nov. 12, 1988, pp. 34-36.

- ^ Greg Tate: Nobody loves a genius Child Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lonesome Flyboy in the 80s Art Boom Buttermilk: The Crisis of Black Artist in White America. In: The Village Voice of November 14, 1989.

- ^ Greg Tate, In: Marshall, Richard (Ed.): Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art 1992. p. 56.

- ↑ Jean-Michel Basquiat's self-portrait auctioned for a record price. In: derStandard.at. May 11, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017 .

- ^ Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) | Untitled | 1980s, Paintings | Christie's In: christies.com , accessed March 21, 2018.

- ↑ Basquiat sells for $ 110.5 million, acquired by entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa , artdaily.org, news from Agence France-Presse .

- ↑ Cheyenne Westphal: The image hunter. In: art-magazin.de. June 30, 2011, archived from the original on September 27, 2011 ; accessed on January 13, 2015 .

- ^ A Basquiat comes of age. In: theartnewspaper.com. June 7, 2010, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban: Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (2nd edition), Penguin Books, 2004, pp. 324, 325.

- ^ New York Beat Movie (1981). In: imdb.com. June 10, 2014, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Sam Keller (ed.): Basquiat . Catalog for the Beyeler retrospective, Hatje Cantz Verlag, S. XXV

- ^ Jean-Michel Basquiat: Artist Biography-Early Training . The Art Story Foundation. 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ↑ Kevin Young: To Repel Ghosts (1st edition), Zoland Books, 2001.

- ↑ Marc Mayer, Fred Hoffman et al: Basquiat , Merrell Publishers, Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- ↑ Almost 110,000 saw a Basquiat retrospective. In: news.ch. September 6, 2010, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Roland Hagenberg's Basquiat photos in museum catalog and film (trailer for the Paris exhibition 2010). In: faz.net. Retrieved January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Le Figaro (video) Exposition Basquiat: les raisons du succès

- ↑ BASQUIAT - SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT In: schirn.de , accessed on March 21, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Basquiat, Jean-Michel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American graffiti artist, painter, and draftsman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 22nd, 1960 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 12, 1988 |

| Place of death | New York City |