Juan van der Hamen y León

Juan van der Hamen (baptized 8. April 1596 in Madrid ; † 28. March 1631 ) was a Spanish painter of the Baroque , whose work in the time of de Oro Siglo fell. His family came from a Flemish background. He and his father served in the Flemish Guard of Archers of the Spanish King. In 1615 he finished his artistic training, about which little is known, and opened his studio. The still life became his artistic and financial mainstay early on. In 1619 he was appointed to the Spanish court, where he sought recognition as a portrait and history painter in order to increase his chances of being appointed court painter. In 1627 he applied for this position without success. Juan van der Hamen died at the age of 35 at a time when he was devoting himself to various genres of painting and had also turned to autonomous landscape painting .

Van der Hamen y León is best known for his still lifes, behind which the other facets of his oeuvre take a back seat. In fact, he was also recognized by his contemporaries for his portraits and history painting. In the 1620s he made a significant contribution to popularizing the still life as an art form at the Madrid court and beyond. After Sánchez Cotán , Juan van der Hamen y León had a decisive influence on this genre in Spain and enriched it with still lifes with flowers and garlands as well as allegories and new forms of composition. However, even in the contemporary reception of baroque art in Spain, van der Hamen was primarily perceived as a painter of still lifes, which became even more pronounced in the period that followed. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that his portraits and history paintings began to attract more research.

Life

Family background

The van der Hamen family originally came from the northern Netherlands near Utrecht , but a branch of theirs had settled in Brussels . Juan van der Hamen y León's father, Jehan van der Hamen, was born in Brussels and served King Philip II between 1581 and 1583 as a soldier on his campaign in Portugal. On June 4, 1586, at the age of about 25, he applied in El Escorial to confirm his Christian origin, which happened the next day. In the second half of 1586 he became a member of the Flemish Guard of Archers and thus a member of the King's Life Guard, for which his origins from the lower Flemish nobility had legitimized him. Shortly after his arrival in Spain, Jehan van der Hamen married Dorotea Whitman Gómez de León, the daughter of another royal archer, and with this marriage also gained ties to a Spanish family of the same rank. The couple settled in San Andrés, the Flemish quarter of Madrid. In the older literature on Spanish painting, it was assumed that Jehan van der Hamen was already a painter. But there is no evidence of this, his career in the Flemish Guard of Archers shows him more as a capable soldier.

childhood and education

Juan van der Hamen y León was baptized on April 8, 1596 as the third son of the van der Hamens. His brothers Pedro and Lorenzo later also made at the court of Philip III. Career. Despite his ancestry, Juan van der Hamen y León was thought to be a Spaniard by his contemporaries. Between 1601 and 1606 Jehan van der Hamen and his family spent most of the time at the court in Valladolid . In 1612, when Juan van der Hamen was 16 years old, his father died.

There is hardly any information about the youth and education of Juan van der Hamen y León. Early biographies assumed that he had first been trained in Flemish and then adapted Spanish elements in his painting, and were mainly based on his name as an indication. Actually instruct his early works Juan van der Hamen rather than Italian art trained painter from what the historical situation in Spain corresponds to the time where as under Philip II. Italian artists in the design of El Escorial had participated . Many Spanish artists also traveled to Italy, but there is no evidence of such a trip for Juan van der Hamen. It is certain that he received his training in Madrid . It stands to reason that he learned from painters who worked at court and who had experience abroad. However, there is no indication of who exactly taught and trained Juan van der Hamen. It could have been leading artistic personalities such as Vicente Carducho , Eugenio Cajés or Felipe Diricksen , who also belongs to the Flemish archers, as indicated by his mastery in the style of the Madrid school. However, due to the inadequate sources, such an assignment cannot be substantiated. As a result, he also trained himself on Sánchez Cotán . In 1615 he probably finished his education.

Start of career and appointment to the court

On March 6, 1615, Juan van der Hamen y León applied to the Vicar General of Madrid for permission to marry 17-year-old Eugenia de Herrera Barnuevo. One of the three character witnesses was the painter Francisco de Herrera , who may have been related to the bride. Juan van der Hamen applied for an immediate marriage without having to wait, as he had to leave Madrid for an important but no longer comprehensible cause. The marriage to Eugenia de Herrera Barnuevo was turned down by van der Hamen's family, who hoped for a better match. Despite this resistance, he married on March 7th. Immediately after the wedding, Juan van der Hamen left Madrid on business, which suggests that he had received an assignment or was assisting an established painter with one. The exact length of his absence from Madrid is unknown, but on May 23, 1616 his son Francisco was baptized.

Between 1615 and 1620 Juan van der Hamen y León built his studio . Although he worked for clients, he also sold pictures freely. In his studio he employed other painters as assistants, of whom he sold lower quality pictures under his name. During these years he also began painting still life , but no works can be assigned. However, he must have already developed his compositions and specialized in certain objects, which then found expression in the well-known works from 1621 onwards. During these years, the young family moved several times within Madrid. She lived first in San Ginés, then in short succession in Santiago and Santa Cruz. Juan van der Hamen's ties to San Andrés, the Flemish quarter, broke after his wedding, and the majority of the couple's friends were Spanish.

In 1619, at the age of 23, Juan van der Hamen y León was appointed to the Spanish court in Madrid. During this time he increasingly turned to still life. At court, van der Hamen probably met the Italian Giovanni Battista Crescenzi , an architect and promoter of naturalistic painting who supported the Spanish King Philip III. enthusiastic about still lifes. The acquisition of one by Juan Sánchez Cotán in 1618 and the appointment of van der Hamen were probably due to his influence . He also owned some still lifes by Juan van der Hamens. The first purchase of one of his fruit still lifes by the king is documented as early as the year he was appointed to the court, which was supposed to complete five still lifes by Cotán, which the king acquired from the estate of Cardinal Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas for the El Pardo hunting lodge in 1519 . The architect Juan Gómez de Mora , who was entrusted with the design of the castle, was associated with van der Hamen throughout his career and acquired pictures from him. Van der Hamen also made a portrait of him, which is next to that of King Philip III. was one of his most valuable works.

Establishment as an artist and at court

As a result, Juan van der Hamen y León became the first major painter in Spain to rely on the still life as a commercial mainstay and regard it as a serious artistic challenge. This direction of his work also showed his knowledge of the development of the art market in other parts of Europe, where in the first two decades of the 17th century the still life was an emerging genre of painting. Despite this openness to the still life, Juan van der Hamen did not want to be committed to it and sought a position as a recognized history and portrait painter that would have given him the prospect of being appointed as an official court painter. One of his first orders for paintings with a religious theme came from the wealthy El Paular Charterhouse in Rascafría near Segovia and is dated around 1619/1620. It is not known whether van der Hamen also had religious commissions. However, he painted other pictures with a religious theme such as San Isidro and John the Baptist praying , both of which were created between 1620 and 1622. The first still lifes signed and dated by Juan van der Hamen date back to 1621 and are still known today.

After the death of his father, Philip IV was proclaimed king on May 2, 1621. Under the new king, Juan van der Hamen seemed to have good opportunities for advancement as a young artist. He tried to be accepted into the Flemish Guard of Archers. In April 1621 he reached the required age of 25 for admission, but there was no vacant position. On January 1, 1622 van der Hamen succeeded Gaspar de Mollegien, but he re-entered the service, so that he lost the position again. On September 25, 1622, with reference to his family tradition, he applied for the next vacancy in the Guard and was accepted in January 1623. Thus Juan van der Hamen belonged to the young king's bodyguard. This gave him free access to the palace, which was expressed in the reception of the courtly flair in his paintings. In his first year in his new position, only a few of the paintings known today were created, which is attributed to the fact that the Guard was particularly challenged as a result of the six-month visit of the Prince of Wales Charles Stuart .

In 1622 van der Hamen's first daughter, María, was born. At that time he was living in the Santiago neighborhood, where the family rented the silversmith Juan de Espinosa near the Palacio Real . In the first two years of Philip IV's reign, Juan van der Hamen y León devoted himself particularly to still life and created works that further shaped Spanish painting. They added to his fame and financial security, even if he deliberately did not limit himself to still lifes. In 1622 he began painting portraits, which was a mainstay of his ambitions at court. In addition to commissioned work by aristocrats and courtiers, he painted the series los ingenios literaros . This series of over 20 paintings documented the relationship to various writers that came about through his brother Lorenzo, who had worked with Lope de Vega . This series meant for van der Hamen on the one hand an artistic reputation, on the other hand the portrayed praised his skills. In the mid-1620s, Juan van der Hamen was a successful and established artist. On October 26, 1624, he accepted Antonio Ponce (1608–1677), his only known student, whose contract has been handed down for three years of training. From 1628, after he had completed his apprenticeship, Ponce was even related to van der Hamen's niece Francisca de Alfaro through his marriage. He adopted the brushwork of his teacher when depicting objects, but often modeled plants in an exaggerated manner, giving them a hard appearance.

Strive for greater recognition at the court

The Juan van der Hamens family made a good living as a result of his position at court. As a member of the Archers Guard, Juan van der Hamen received 159 reales a month, as well as funding for accommodation, free medical care, bread rations and a pension. With these privileges he was better off than the court painters up to Velázquez , while their basic income was at the same level. On June 29, 1623, the second daughter Ana María was baptized, but she died a short time later.

In 1625 the family moved to their widowed sister-in-law, who also lived in the Santiago district, where Juan van der Hamen lived until his death. Shortly before, he painted some pictures for the Trinitarios Calzados monastery in Madrid, the construction of which began shortly before the end of the reign of Philip II. It is no longer known which pictures Juan van der Hamen painted, but they were related to those that Eugenio Cajés , a highly respected painter at the court, had painted. This commission may have overlapped with his work for the Real Monasterio de la Encarnación , for which Juan van der Hamen made a series of pictures dated to 1625. His most important work for this monastery was The Adoration of the Apocalyptic Lamb, which was placed in the chapel donated by the Condesa de Miranda. While Juan van der Hamen was working on this commission, he probably met the art theorist Francisco Pacheco del Río . He later stated that van der Hamen was not pleased with his fame as a still life painter and the associated reduced attention for his other works. He saw this assessment as contrary to his efforts to further establish himself at court. Nevertheless, his portraits were also valued at this time.

One of Juan van der Hamen's greatest supporters at court was Jean de Croÿ , the Comte de Solre and captain of the royal guard of archers. He owned gardens in which van der Hamen could study the plants and collected paintings. He was open to new genres such as landscape painting and still life. Although only a few paintings can be exactly assigned, it is certain that the Comte de Solre owned a large number of works by Juan van der Hamen, including probably landscapes to which van der Hamen had turned towards the end of his life. Another sponsor was Diego Mexía Felípez de Guzmán , the Marqués de Leganés , who owned arguably the largest collection of van der Hamen's works, including some of his best paintings. While there is no record of the purchases and the relationship between the painter and the patron, given the size of the collection, a closer connection between the two can be assumed. This is also important because the Marqués was an influential patron who even advised the king, and thus seemed conducive to van der Hamen's further rise.

There was a rival relationship at court between Diego Velázquez and Juan van der Hamen. While Velázquez was mainly supported by Pacheco, Cardinal Francesco Barberini seemed to support van der Hamen during his stay in Spain in 1626. He had portraits made by both painters and, as is documented by Cassiano dal Pozzo , preferred the work of van der Hamen. In addition, Juan van der Hamen y León received support from Juan Gómez de Mora , who worked in the royal administration and had been associated with the painter since his first commission at court in 1619. According to Pacheco, Velázquez had the privilege of being the only one to portray the king and his queen, but van der Hamen also made such portraits from the paintings of his competitor. Juan van der Hamen tried in vain for the position of court painter in 1627 after Bartolomé González died and one of the four official court painter positions became vacant. He registered on November 5, 1627 for the competition, in which eleven other painters took part and whose judges were the three court painters Velázquez, Carducho and Cajés. Antonio de Lanchardes emerged as the winner, but could not take the position due to financial problems of the king. Van der Hamen probably didn't get the position because he was best known for his still lifes. However, after he had previously achieved greater fame as a portraitist and could have been dangerous in the Velázquez area, it is also possible that there were tactical reasons for not being considered.

Last years of life and death

As a result of Peter Paul Rubens' presence at the Spanish court in 1628 and 1629, the popularity of Flemish painting increased there. In this changing climate, Velázquez in particular was able to assert himself, but Juan van der Hamen also succeeded in receiving royal commissions. So he painted two paintings for the decoration of the king's apartment in his summer residence. In the large vestibule of the royal bedroom, there were two paintings by van der Hamen, as well as Flemish paintings. They were the only Spanish in the room. This order was probably mediated by Juan Gómez de Mora. Van der Hamen was able to sell a total of three paintings to the king, for which a total of 3,000 reales is listed in the documents. One of the pictures was Boy, Carrying a Fruit Bowl, who redeemed just as much with 1100 reales as The Meal of Bacchus of Velázquez, his first history painting acquired by the king. This suggests that van der Hamen and Velázquez were classified by their contemporaries as being much more equal than they appear in retrospect.

From 1628 Juan van der Hamen turned to new pictorial forms. So he introduced the motif of the flower garland in Spanish painting and was one of the first Spaniards to paint autonomous flower still lifes and landscapes. And beyond the motif, there were innovations in van der Hamen's painting. So now copper plates and wooden panels were used as painting grounds , and he also painted octagonal and round formats. But he also continued to work in the courtly environment. He made the painting The Virgin Mary presents the baby Jesus to St. Francis, which the art writer Antonio Palomino de Castro y Velasco described almost a century later as being ahead of his time, for the Real Monasterio de San Gil . In the late 1620s, van der Hamen painted not only for the king, but also for his brother Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand , the Archbishop of Toledo . He was the patron saint of the Convento de Santa Isabel de los Reyes in 1630 and 1631 and probably commissioned the painting The Virgin Appears to Saint Francis from Juan van der Hamen. In addition, van der Hamen worked on works for the Galería del Infante, but could not finish this work for the Cardinal Infante because of his death. The four paintings that he made for this commission were worth a total of 100,980 maravedíes (around 290 ducats).

In the first three months of 1631 Juan van der Hamen was very active artistically. He sold works and worked on others, as the larger number of unfinished works in the estate suggests. On February 3, he accepted the order to compile the inventory of an inheritance, but could no longer do this. On March 28, 1631 Juan van der Hamen y León died unexpectedly. The cause of death and a possible illness are not known, he had no more time to write a last will, to confess and to receive the final rites. On April 4, the widow Eugenia de Herrera commissioned an inventory of her husband's property. It took several months to create. It included paintings, plaster models, weapons, furniture, tapestries, books, gold, silver, and jewelry. The studio comprised 150 paintings, only a small part of which were still lifes. It also comprised 900 engravings, which probably served as templates. Alonso Pérez de Montalban took care of the interests of the underage children .

plant

Still life

About 70 still lifes by Juan van der Hamen y León are known, about half of which were created in 1621 and 1622. The first dated works refer to the year 1621, but van der Hamen must have made such paintings beforehand, as he was already using the compositional structure and pictorial elements typical of him. In addition to classic still lifes, van der Hamen also painted mixed forms such as paintings with elements of the still life, whose main focus, however, was on the allegorical representation, or flower garlands that enclosed another motif. The latest in Spain were an innovation by Juan van der Hamen y León, who explored the possibilities of this pictorial form.

Juan van der Hamen y León introduced two new forms of composition into Spanish still life painting: the symmetrical composition principle and the three-tier composition. Both went back to ancient models that he might have got to know through the Italian art and antique collector Cassiano dal Pozzo or Giovanni Battista Crescenzi . Overall, Juan van der Hamen did not follow Juan Sánchez Cotán so much in this genre , but received still life painters from other parts of Europe and, with the decision for this genre, also pursued more commercial interests. He knew still lifes from Italy, Flanders and the Netherlands, which were in Spanish collections, and turned to their very representational style of representation, which was in contrast to Velázquez with his moralizing and anecdotal pictures, which also showed people.

Early still life

According to the art historian Felix Scheffler, the first known still life by Juan van der Hamen y León is the picture Still Life with Fruit Bowl, Birds and Window View from 1621, which formed a pair of pictures with a painting of the same name from 1623. It was a copy of a still life with the same title by the Flemish painter Frans Snyders . Van der Hamen also received Snyders in other motifs. The painting Still Life with Fruits and Sweets with Monkeys, probably completed by his workshop, was based on Snyders' painting Fruits, Monkeys and Birds . The monkeys are not copied, but their mischievous depiction is borrowed from the Flemish. In further still lifes, Juan van der Hamen broke away from the Flemish models a little by replacing the Chinese porcelain popular in the Netherlands with a woven wicker basket and showing hanging fruits next to the bowl arrangement by Sanchez Cotán. In 1622 he made the portrait-format painting Still Life with a Hanging Grape and Goldfinch , which with the dark, undifferentiated background, the fruit hanging without visible attachment and the angular stone tray clearly reverted to typical Spanish still life elements in the tradition of Cotán.

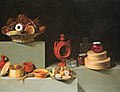

But he went beyond that and developed his own style, which he had adapted to court conditions. Although he mostly painted fruit, vegetables and game, he also gave the pictures the appearance of luxury, such as the representation of glassware. He also showed ceramics from Talavera de la Reina , Mexican ceramics, Chinese porcelain and table silver . Van der Hamen also introduced the sugar-refined food culture as a subject in Spanish painting. In doing so, he broke away from the mere representation of the fruits and other goods in their natural state and showed them, for example, preserved and preserved, denatured and only identifiable through the packaging. In the still life with turrones from 1622, Juan van der Hamen decided against arranging the objects parallel to the picture and positioned a glass and a bowl on a chipboard box containing fruit jelly to make better use of the picture space. With this he already anticipated his three-stage compositions of later years. In addition, the picture is dominated by an unusually large number of angular shapes.

Van der Hamen developed compositional principles, which he often repeated in slightly modified form. The first is the principle of baskets, boxes and glasses with sweets, the second is arranged around a large, green Venetian glass bowl and the third is the composition with baskets full of peas and cherries. An example of the composition with the symmetrical tripartite division around the Venetian glass bowl with a faun's head is the picture Still Life with Fruit Bowl and Hanging Grapes from 1622. The influence of German or Dutch models was significantly less in these pictures than the antique models, whose echoes in the Research have been proven.

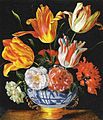

Two paintings by Juan van der Hamens that stand out from the Spanish still life production are the still life couple with flower vases, dog and puppies playing ball from the mid-1620s. They were commissioned for Jean de Croÿ , captain of the Spanish king's bodyguard, and framed a doorway or were even attached to the door leaves. Conceptually it was about trampantojos, trompe-l'œils , which continued the Catalan tile floor into the picture. The composition follows the three-part symmetrical structure that is typical of many of Juan van der Hamen's works, but in this case is monumentally exaggerated by the height of the bouquets. The framing chipboard boxes, candy, French table clock and Venetian glasses are clearly dominated. The dog portraits in the lower half of the picture exist autonomously from the table still lifes. The Swiss Mountain Dogs make the paintings directly into a courtly context, because such Hundebildnisse were usually shown in portraits of nobles. The two extensive bouquets were early examples of Flemish-inspired flower painting in Spain. The flowers are not painted from nature, but come from different blooming times and are freely composed according to color and shape contrasts and picture filling, which is why the bouquets are actually too big for the vase openings are. Individual blossoms such as the sunflower refer to their own studies of nature in their detailed execution.

Juan van der Hamen y León, fruit plate, hanging grapes and flower vase, 78 × 41 cm, oil on canvas, 1622, Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León, fruit basket with hanging grapes and vases made of terracotta and glass, 66.5 × 103.5 cm, oil on canvas, 1623, private collection in Paris

Late still life

In 1626 Juan van der Hamen y León introduced the three-level composition type into Spanish still life painting with the painting Still Life with Pomegranates and Precious Glass . With the representation at different height levels in front of a neutral background, he intended to show as many objects as possible from a full view without overlapping. In addition to the function for the presentation of objects, this form of composition also restructured the image space. Hamen y León used this type of image until his death. The pictures are characterized by the color contrast between the gray stone steps and the objects shown, as well as by the contrast of the massive, hard and right-angled steps with the round and organic shapes. In doing so, Juan van der Hamen only kept perspective regularities very loosely, which causes irritation in the viewer about the viewing angle and the view of the steps. Courtly representation or the storage and presentation of goods in pantries and shop window decorations were assumed to be the background to the emergence of this type, but ancient models inherent in art are far more likely. The visit of Cardinal Francesco Barberini accompanied by Cassiano dal Pozzo at the Madrid court is seen in a special context . Dal Pozzo met Juan van der Hamen y León and may have shown him sketches of ancient Roman models. Even Giovanni Battista Crescenzi could have made the van Hamen acquainted with these models. Another possibility would be Roman mosaics , which he himself might have seen in Spain. Van der Hamen used recurring objects as in his early still lifes, but in most cases he varied the compositions significantly.

Two of his largest still lifes with the couple Still Life with Flowers and Fruit and Still Life with Fruit and Glassware, both painted in 1629, date from this period . Both pictures are characterized by their splendid decor and virtuosity in their presentation. Many of the elements used in them can be found in other pictures by van der Hamen. Other, smaller still lifes, which were also created at this time, are partly borrowed from these.

His late still lifes also include those that had tables with furnishings as the theme. Examples are Das Gabelfrühstück and Die Zwischenmahlzeit, the latter dated to the year of his death. The picture of a sideboard with tableware and food stems from his early work , but the later works are much more freely composed. These pictures are in the tradition of Northern European meal still lifes , such as those painted by Pieter Claesz , but are much more reduced and not as opulent.

When Juan van der Hamen died in 1631, 14 small fruit still lifes were recorded in the inventory of his studio, which probably showed individual fruit plates or other smaller motifs. Some of these paintings are still known today. It is not entirely certain whether they were intended for sale or as role models for inclusion in larger still lifes. Since the directory also contains preliminary drawings for such paintings after death, the former suggests more. In addition, in some inventories of the 17th century there are paintings under the name plates with fruits, which were ascribed to van der Hamen. There were also twelve other small paintings in the studio inventory that showed fruit. These paintings also served as models for his successors after his death. In this way, certain elements can be found in paintings from this environment. Among the most outstanding works by Juan van der Hamens in this group of works are plates with plums and morello cherries and plates with pomegranates .

Juan van der Hamen y León, Still Life with Sweets and Ceramics, 84.2 × 112.8 cm, oil on canvas, 1627, National Gallery of Art , Washington, DC

Juan van der Hamen y León, Still Life with Flowers and Fruit, 84 × 131 cm, oil on canvas, 1629, Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York

Allegories

Allegorical representations were rare in Spain. Juan van der Hamen y León painted in 1626 and 1627 Pomona and Vertumnus as an allegory of autumn and an offering to Flora as an allegory of spring. The first picture shows, inspired by Ovid's Metamorphoses , the goddess of fruit growing and horticulture Pomonas with the god of change, prosperity and autumn Vertumnus . Pomona's right hand rests on the opening of a cornucopia from which peaches, quinces, apples, grapes, apricots, pomegranates, cherries, plums, melons, pumpkins, peppers, radishes and an artichoke, lemon and cardon each pour out and form a barrier in the foreground of the picture . Vertumnus is holding a basket of grapes and apples. The depiction of the goddess of flowers and the spring flora shows a woman crowned with a wreath of flowers in a court garden, who is offered a basket of roses by a boy. Juan van der Hamen y León added the fruits and flowers to the mythological figures in the manner of a still life, but the pictures show that the painter was able to paint figures convincingly. This was in contrast to his exclusive perception as a good still life painter.

Juan van der Hamen y León, Pomona and Vertumnus 229 × 149 cm, oil on canvas, 1626, Banco de España in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León, Offering to Flora , 216 × 140 cm, oil on canvas, 1627, Museo del Prado in Madrid

Garlands

Juan van der Hamen y León introduced the garland as a motif in Spanish painting in 1628. This led to the fact that he experimented with the new subject for the first two paintings of this kind, Garland with Landscape , and tried out different motifs for the circle section. These can be proven by x-rays and also prove that the two paintings were created at the same time. First, Juan van der Hamen chose female saints, then two Old Testament scenes and finally came to the solution with the two landscapes. Today only the rear part of the landscape on the left half of the picture is preserved in both paintings, the foreground was lost due to improper restorations and is now painted over dark because the underpainting shone through. These two paintings are exceptions in van der Hamen's work, as he filled other garlands with religious motifs.

This is how the garland with the immaculate conception, the virgin with child in the Gorie and the garland with the sleeping baby Jesus were created . The former picture in particular is very well preserved. On the basis of the diverse selection of flowers compared to the garland with landscape of the Hood Museum, it can be proven that Juan van der Hamen used the same preliminary drawings for them. For example, the White Star of Bethlehem and the white lilies are the same in both images. The preliminary drawings were made in the royal gardens and in the gardens of his sponsor, the Comte de Soler, which also made the variety of flower species possible. The figure representation in the garland with the immaculate conception is not as convincing, especially in the face, as in the portraits of van der Hamen, which is attributed to the smaller format. The garland with the sleeping Jesus child with the attributes of the crown of thorns , the nails and dice refers to the image type Jesus child triumphant over death . Juan van der Hamen referred in his depiction to the ancient motif of the sleeping Eros on a skull. The depictions of birds in this painting are extraordinary. While the bee eater on the cross refers to the resurrection, the goldfinch connects the garland with the medallion. Juan van der Hamen was a pioneer with this painting; other paintings of this type did not appear until the middle of the 17th century.

Autonomous floral still life

At the end of the 1620s, Juan van der Hamen y León also painted some of the first autonomous flower still lifes in Spain. The inventory of his studio, which was put up after his death, contained 24 flower pictures, but no signed copies have survived. William B. Jordan tried to attribute two flower still lifes to van der Hamen, but this is not certain. He established this in the blue glow of the Chinese porcelain, the chiaroscuro of the tulips , the free ductus of the roses and the similarities to flowers that were in the garlands.

Portraits

Juan van der Hamen y León was a recognized portrait painter . He began to turn to this genre in 1622, which, in contrast to the still lifes, supported his ambitions at court. In addition to commissioned work for aristocrats and courtiers, he made a series of over twenty portraits that showed famous writers and established his reputation as a portraitist. In the inventory of his studio after his death, twenty of these works were listed under one item, which separated them as a fixed group of works from the individually listed portraits. The writers themselves modeled the busts called los ingenios literaros . Some of the sitters are named in the estate's estimate. There were Lope de Vega , Francisco de Quevedo , Luis de Góngora , José de Valdivielso , Juan Pérez de Montalbán , Juan Ruiz de Alarcón , Francisco de la Cueva y Silva , Fracisco de Rioja , Jerónimo de Huerta , Luis Pacheco Naváes , Luis de Torres and Catalina de Erauso , all of whom were important figures in the Spanish literature of the Siglo de Oro, among those portrayed. Many of them also praised van der Hamen's portraiture and painting. The series also includes a portrait of his brother Lorenzo van der Hamen y León .

The chronological classification of the series in the work of Juan van der Hamen is difficult, since most of the paintings are not dated. However, due to the age of the person depicted, the portrait of his brother suggests that Juan van der Hamen may have started work on this series as early as 1620. It shows a quite spontaneous and fluid style, which differs from his court portraits, in which he revived the very conservative style from the time of Philip II. The style of the portraits could, however, also be less lively and therefore stronger and more rigorous, as is the case with the portrait of Don Francisco de la Cueva y Silva . This picture also shows how van der Hamen used his skills as a still life painter in some portraits. He used the books on the right edge of the picture to charge the picture with meaning. The head is modeled by the light in contrast to the black clothing, as are the hands, which are given a special presence in the picture. The focus on the volume and details of the head is somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of objects in van der Hamens still lifes. Van der Hamen kept these portraits in his studio and commissioned them to paint versions of them for his customers. The portrait of Don Francisco de la Cueva y Silva was acquired by the Marqués de Leganés, who owned eight of the portraits.

With the portrait of Catalina de Erauso, which was recently convincingly attributed to Juan van der Hamen y León and is also one of the los ingenios literaros , he created one of the most bizarre portraits in Spanish painting. The picture painted in 1626 shows the runaway nun Catalina de Erauso, disguised as a man and was controversial among contemporaries. One of his portraits, probably carried out rather quickly and in a study-like manner, is the head of a cleric, who shows van der Hamen's quality of painting lively figures that stand out from the more formal portraits and also the figures of some of his history paintings. In 1971, Diego Angulo Iñiguez published a portrait that stood out from the rest of van der Hamen's work and clearly referred to his courtly ambitions. It is the painting Jean de Croÿ, II Comte de Solre, which was also made in 1626. It is considered to be one of the most outstanding portraits created at the Spanish court in the 1620s. The picture shows the Comte de Solre against a black background in the golden armor of a knight from the Order of the Golden Tile, who stands next to a table covered with a red velvet cloth. Van der Hamen created a dramatic lighting atmosphere and used a very warm color scheme, which is only broken by the white fur of the Dalmatian . The portrait is characterized by Juan van der Hamen's ability to translate the weight and structure of the objects represented onto the canvas.

Another important work is the portrait of a dwarf, which van der Hamen painted around 1626 and which was also in the collection of the Marqués de Leganés. The painting shows a strongly naturalistic representation and stands with the strong colors and the intense contrast of light and shadow in the tradition of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio . Juan van der Hamen y León also met the demand for portraits of the royal couple. Velazquéz was the only painter to whom the king sat as a model, but his workshop could not meet the great demand. Therefore, a large number of painters made paintings based on the portraits of Velazquéz. Van der Hamen organized the painting of these pictures particularly efficiently. The portrait of Philip IV, for example, is very similar to that of Velazquéz in terms of the face and pose, but it differs significantly in the rich and detailed decoration of the clothing. Both the representation of the king and his queen Isabel de Borbón are characterized by a strong chiaroscuro , which gives them a great presence despite the focus on the costume representation. The portraits of Philipp IV, Isabel de Borbón and Doña Margarita de Austria , which are known today , cannot be ascribed to van der Hamen with absolute certainty, but their execution shows clear parallels to Jean de Croÿ, II Comte de Solre . The portrait of Infanta María de Austria, Reina de Hungría is also included in this group of works . Especially when comparing this picture with the portrait of Isabél de Borbón , the origin of an efficiently working studio becomes clear. The contours of the dresses are almost identical and the pose with the arm resting on the back of the chair and the handkerchiefs held in the left hand refer to a common preliminary drawing that was used for both portraits.

There were significant differences in value in the portraits. For example, van der Hamen sold oil sketches of the head of Cardinal Francesco Barberini for 10 reales, while he was able to redeem 200 reales for a full-length portrait of King Philip IV. The pictures in the scholarly series were also priced differently depending on the degree of their execution and ranged from 33 to 44 reales and more.

Juan van der Hamen y León (?), Philip IV, 199 × 115.5 cm, oil on canvas, Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León (?), Isabel de Borbón, 199.2 × 115 cm, oil on canvas, Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León (?), Infanta María de Austria, Reine de Hungría, 191 × 103 cm, oil on canvas, Musée Fesch in Ajaccio

Juan van der Hamen y León (?), Doña Margarita de Austria, 198 × 117.5 cm, oil on canvas, Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan in Madrid

History painting

The first known history paintings by Juan van der Hamen y León date from the period between 1620 and 1622. The picture of San Isidro was a popular motif in Madrid at the time, so that by choosing this subject, van der Hamen also responded to a customer demand. The painting is characterized, as well as the simultaneously generated John the Baptist in prayer , by a strong tenebrist from which models the figures.

In the mid-1620s, Juan van der Hamen began to devote himself more to history painting. This is also in connection with his position at court and his striving for further official recognition, which he believed he could only achieve through the classic, recognized genres of history and portrait. He increasingly painted paintings for monasteries that were donated by the nobles at court. An important work of this phase was The Adoration of the Apocalyptic Lamb, which he painted for the Real Monasterio de la Encarnación . In this painting Juan van der Hamen took up the theological writings of his brother Lorenzo, who was also portrayed as Saint Lawrence on the far left of the picture. In the figures he referred in some cases to people connected to the monastery. Overall, this picture expresses the ambivalence that can be demonstrated in most of van der Hamen's histories. The large figures in the foreground are full of character and convincingly, while the figures in the sky around the lamb appear archaic and schematic. In addition to this large altar painting, there are other paintings by van der Hamens in this monastery, which were installed over ceramic altars from Talavera de la Reina , but are no longer in their original location in the monastery. One of these is the picture of John the Baptist, which shows his naturalistic style and his ability as an animal painter on the sheep's fur.

In 1628 van der Hamen painted the painting The Virgin Mary presents the baby Jesus to St. Francis for the Real Monasterio de San Gil . It relates to the reform efforts of the late 16th century in the Franciscan order and shows a vision that dates before the stigmatization of Francis . This motif was coined in Italy by the brothers Agostino and Annibale Carracci , van der Hamen was probably one of the first Spaniards to adapt it. Another unsecured work for this monastery could have been Christ on the pillar . It is a slightly modified copy of a painting by Orazio Borgianni , which he painted in Pamplona in 1601 . The chiaroscuro , which roughly corresponds to that of John the Baptist , speaks for the fact that Juan van der Hamen painted the picture . The painting The Virgin Appears to Saint Francis, which was probably also painted for a Franciscan monastery between 1630 and 1631, is in the ideological context of the attempt by this order and the Spanish crown to secure papal recognition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception . Van der Hamen used the same face for Francis as in his 1628 painting, but this time his hands show the wounds. Overall, the figure is presented very convincingly. Maria is reminiscent of Italian models and materializes through depictions of flowers. It is a rare motif, but it was also treated by other painters at the court such as Carducho.

Another history painting attributed to van der Hamen is the image of Abraham and the three angels . It covers an Old Testament theme popular in Spain at the beginning of the 17th century. The story of Abraham , to whom God appears in the form of three angels, is one of the motifs in which the commandment of hospitality towards strangers, which is important in Spain, was negotiated. The picture is attributed to van der Hamen on the basis of stylistic analyzes. In it he combines his abilities to tell the Historia and at the same time to represent the various objects in their own texture and physicality, as he did in his still lifes. In addition to these paintings that are known today, there were other histories that Juan van der Hamen painted. Most of them have either been lost or are hidden in collections. In the inventory of the studio after his death there are several more history paintings, some of them not yet completed. In addition, such paintings by van der Hamen can be found in some collection inventories from the 17th century. Research suggests that he was able to sell many such paintings and some may even have ended up abroad.

Juan van der Hamen y León, John the Baptist, 168 × 140 cm, oil on canvas, 1625, Real Monasterio de la Encarnación in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León, The penitent Saint Peter, 87.3 × 130.8 cm, oil on canvas, 1625, Real Monasterio de la Encarnación in Madrid

Juan van der Hamen y León, The Virgin presents the Christ Child to Saint Francis, 236 × 138 cm, oil on canvas, Blondeau Associés in Paris

Landscapes

Juan van der Hamen y León painted some of the first autonomous landscape paintings in Spain in the late 1620s , but these have not survived. When estimating his studio after his death, 22 landscapes were listed, some of which were not completed. They were quite small formats of 21 or 28 centimeters, five of them were round.

In some of his still lifes a turn towards the landscape can already be discerned, such as in the still life with cardoon and a winter landscape or in the two still lifes with a bowl of fruit, birds and a window view . From these, conclusions are drawn about the possible appearance of his independent paintings of this genre. The garlands with landscape come closest to independent landscapes . They both show a light and lively style of painting in the intact parts of the picture, which create an atmospheric effect. Both also show that van der Hamen dominated different types of landscape. Once a northern landscape in the picture of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College , while the painting in the Meadows Museum of Southern Methodist University shows a more classical landscape. With these landscapes, Juan van der Hamen is close to those of Francisco Collante , who started this genre around the same time, and those of his friend Pedro Núñez de Valle . Apart from that, the backgrounds of his history paintings were also used to draw conclusions about the independent landscapes. For example, John the Baptist at prayer, John the Baptist and The Spacious Saint Peter each show very different, atmospheric landscapes that were executed relatively freely.

At the wedding of María van der Hamen y León in 1639, she still owned 13 landscape paintings by her father. A landscape was in 1638 owned by Juan María Forno, the house Meier of Giovanni Battista Crescenzi , twelve more appeared in 1642 in the collection of inventory Gregorio Guión on. Today van der Hamen's landscapes are no longer known.

reception

Artistic aftermath

After the death of Juan van der Hamen y León, there must have been further activities in his studio on Calle de Fuentes for some time. Otherwise the existence of a large number of still lifes, which were clearly in his tradition and used the same models, could not be explained. The most important figure in this context is Antonio Ponce , who was trained by van der Hamen and married into his family. A large number of still lifes originate from him, which refer very directly to Van der Hamen's models and largely imitate his style. In doing so, he did not achieve the virtuosity of his master; Particularly characteristic of this is a series of monthly pictures in which many of Juan van der Hamen's motifs appear. In his Still Life with Candy Boxes and Fruit Plates , Ponce made clear references to boxes and jars of candy . This very direct reference in a large number of works indicates that Ponce had little originality or only had to emancipate himself from his master and his workshop over time.

There are also three other still lifes, possibly by Francisco van der Hamen y León, son of Juan van der Hamens. After his marriage at the age of 18 in 1634, he took over his father's preliminary drawings. The style and composition are very different from the monthly pictures of Ponce. The still lifes are designed symmetrically and show hanging fruits. They stand in the tradition of the works of Juan van der Hamen, but do not come close to this in terms of execution. However, since no signed painting by Francisco van der Hamen y León is known, the hypothesis of his authorship cannot be confirmed.

There are also three paintings that were created by an unknown artist, and van der Hamens added two allegories. They are not similar stylistically or compositionally, but they do capture the impression of these works. However, the artist copied the figure of Vertumnus in his Allegory of Summer . Overall, these works are more in the style of Peter Paul Rubens .

Antonio Ponce , The Month of April, Private Collection

Contemporary rating

Juan Pérez de Montalbán wrote about Juan van der Hamen y León in his work Para todos , published in 1632 : “Juan van der Hamen y León was one of the most celebrated painters of our century because he exceeded his maturity in his drawings, paintings and narrative works. And in addition to his uniqueness in his art, he wrote extraordinary verses that demonstrated the interrelationship between painting and poetry. He died very young, but from the fruits, portraits and large canvases he left behind, we can conclude that he would be the greatest Spanish painter if he were still alive. ”In Para todos de Montalbán described important personalities at the Madrid court, Juan van der Hamen y León was the only painter in this selection. In addition, other authors such as Luis de Góngora , Gabriel Bocángel , Lope de Vega and his brother Lorenzo van der Hamen y León also praised van der Hamen's artistic skills.

The art theorist Francisco Pacheco del Río listed Juan van der Hamen y León in his work Arte de la pintura , published in 1649, as an example for painters of outstanding flower and fruit still lifes. He wrote: “I have also tried this exercise and that of flower painting and do not consider it very difficult. Juan van der Hamen painted them extremely well, and he painted the sweets even better, surpassing the figures and portraits he made with this painting, which, to his annoyance, earned him greater fame. ”This annoyance described by van der Hamens can be traced back to the equation of the painted object and the real model and the disdain for this genre in most writings on art theory. A reference to the Zeuxis legend can also be established. Vicente Carducho and Rodrigo de Holanda attached great importance to the recourse to antiquity when assessing still lifes, in addition to imitating nature. Van der Hamen was seen in this context as the painter who brought the ancient art of still life into the modern age and did this in his art and did not just leave the reception of antiquity in the ekphrasis .

Research history

For a long time, the information known about Juan van der Hamen y León was based primarily on the work of Julio Cavestany de Anduaga , who curated the first large and important exhibition on Spanish still life, Floreros y bodegones en la pintura española , in 1935 . The publication published on the occasion of this exhibition and not published until 1940 as a result of the Spanish Civil War was decisive until the 1960s. In 1962, José López Navío published the inventory of the collection of the Marqués de Leganés, in which he also contributed further information about van der Hamen y León as a portrait and still life painter. In 1965, van der Hamen y León's religious paintings were also made available to the public and research when the Patrimonio Nacional opened the Real Monasterio de la Encarnación . That there are works by van der Hamen was published by Elías Tormo as early as 1917 .

The art historian William B. Jordan has dealt intensively with Juan van der Hamen y León since the 1960s. His two-volume dissertation from 1967 was an early monograph on the painter, but is only available in a few large art libraries. In it, Jordan named the three-level composition type for the first time. He also evaluated new archive material such as van der Hamen's estate and documents relating to the care for his children in the Archivo de Protocolos de Madrid , his marriage documents in the archbishop of Madrid and documents relating to his position at court in the Archive General de Simanca and the archives of the Royal Palace in Madrid. Jordan also found genealogical documents on Jan van der Hamen's brother Lorenzo in the archives of the Archbishop's Palace in Grenada, which also contained information on the other family members. Thus, Jordan was able to present a comprehensive and reliable biography of van der Hamen for the first time. As a result, he undertook several stays in Spain with the aim of submitting another monograph, which he did not complete. However, he was able to find out about van in the catalogs “Spanish Style Life in the Golden Age 1600–1650” ( Fort Worth , Kimbell Art Museum , 1985) and “Spanish Still Life from Velázquez to Goya” ( London , National Gallery , 1995) update the hats. Jordan curated “Juan van der Hamen y León and the Court of Madrid” , which was shown in Madrid and Dallas in 2005 and 2006, the first monographic exhibition on this artist. In it, van der Hamen y León's work as a history painter and portraitist was juxtaposed with still lifes on an equal footing. In addition, Jordan presented some works that could potentially be attributed to him. The catalog published on the occasion of this exhibition is the most recent monograph on Juan van der Hamen y León. William B. Jordan continues to pursue the project of a catalog raisonné on Juan van der Hamen y León.

literature

- William B. Jordan : Juan van der Hamen y León & The Court of Madrid . Yale University Press, New Haven 2005. ISBN 0-300-11318-8 .

- Ira Oppermann: The Spanish Still Life in the 17th Century. From the windowless room to the light-flooded landscape . Reimer, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-496-01368-6 .

- Felix Scheffler: The Spanish still life of the 17th century: theory, genesis and development of a new pictorial genre . Vervuert, Frankfurt am Main 2000. ISBN 3-89354-515-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Oppermann, p. 23.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 45.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 40.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 46-47.

- ↑ a b Oppermann, p. 23.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 24.

- ↑ a b c Jordan, p. 51.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Oppermann, p. 27.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 75.

- ↑ a b c Jordan, p. 73.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 74.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 54-57.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 59.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 60-61.

- ↑ a b Scheffler, p. 316.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 124.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 119.

- ^ Jordan, p. 120.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 70.

- ↑ Oppermann, p. 29.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 131.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 147.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 170.

- ^ Jordan, p. 176.

- ^ Jordan, p. 183.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 202.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 207.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 212-213.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 217.

- ^ Jordan, p. 226.

- ^ Jordan, p. 229.

- ↑ a b c Jordan, p. 233.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 251.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 252.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 264-265.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 284.

- ^ Jordan, p. 285.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 74.

- ↑ Oppermann, p. 26.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 220.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 106-107.

- ↑ a b Scheffler, p. 321.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 317.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 80, 90 and 97.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 267.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 329.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 330.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 261.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 267.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 262.

- ↑ Scheffler, pp. 262-263.

- ↑ Scheffler, pp. 264-265.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 270.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 281.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 282.

- ^ Jordan, p. 192.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 278.

- ↑ a b Gerd-Helge Vogel: How did the plants get into painting - on the botanical representation in European art between the late Gothic and Biedermeier periods. In: Gerd-Helge Vogel (Hrsg.): Plants, flowers, fruits - botanical illustrations in art and science. Lukas, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86732-198-3 , p. 48.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 398.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 399.

- ^ Jordan, p. 237.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 147-148.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 120.

- ↑ a b Jordan, pp. 151-152.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 158.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 153.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 171.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 197-198.

- ^ Jordan, p. 219.

- ^ Jordan, p. 220.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 63.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 135.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 134.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 137.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 254-255.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 255.

- ↑ Jordan, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Jordan, p. 258.

- ^ Jordan, p. 233.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 248.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 249.

- ^ Jordan, p. 286.

- ^ Jordan, p. 287.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 290.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 291.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 293.

- ↑ freely translated from Jordan, p. 15: “Juan de Vanderhamen y León, among the most celebrated painters of our century, because in drawing, painting, and narrative works he surpassed Mature herself. And aside from being unique in his art, he composed extraordinary verses with which he proved the interrelationship of painting and poetry. He died very young, and from what he left us in fruits, as well as in portraits and large canvases, one deduces that if he were living, he would have been the greatest Spaniard of his art. "

- ^ Pacheco, Arte de la pintura (Sevilla 1649), edited by Bonaventure Bassegoda i Hugas, Madrid 1990, p. 511.

- ↑ Translation Scheffler, p. 94 after Pacheco, (1649) 1990, p. 512: “Tambien he probado este exercisio, y el de las flores, que jusgo no ser muy dificil. Juan Vanderramen los hizo extremadamente, y mejor los dulces, aventajándose en esta parte a las figurasy retratos que hacía y, así, esto le dio, a su despecho, mayor nombre. "

- ↑ Scheffler, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 149.

- ↑ Jordan, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Jordan, p. 17.

- ↑ a b Oppermann, p. 15.

- ^ William B. Jordan, Juan van der Hamen y León, 2 vol., Diss. New York University 1967, University Microfilm International, Ann Arbor.

- ↑ Scheffler, p. 261.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hamen y León, Juan van der |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | baptized April 8, 1596 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Madrid |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1631 |

| Place of death | Madrid |