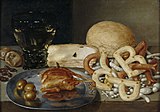

Meal still life

|

| Still life with a fish meal, ham and cherries |

|---|

| Jacob van Hulsdonck , 1614 |

| Oil paint on a wooden panel |

| 65.4 x 106.8 cm |

| The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, Durham county , UK |

The meal still life is a special form of the still life . Tables are shown with food, dishes and other objects on them, and in some cases animals such as insects. The meal still life has existed in art since the autonomy of the still life as a separate genre around 1600 and had its heyday in the first half of the 17th century. The term meal still life is synonymous with: Banket (je) , Ontbijt (je) , Laid table , Breakfast-piece , Banquet piece , Snackstillleben and Breakfast still life .

Concept history

Since the meal still life was created at the beginning of the 17th century, names for such paintings can only be traced back to the 17th century. Even before the word stilleven appeared in Dutch inventories for the first time around 1650, painting names such as “Een bancket schilderytgen” (1624), “Een bancketgen met een pastey” (1624), “Een cleyn viercant bancquetien van een schuttel met appelen en” were already in use moerbesien met een witte broodt ”(1627) or“ Een ontbytgen van een pekelharingh ”(1627) common.

Ingvar Bergström established the English term “Breakfast-Piece” with his dissertation Dutch Still-Life Painting in the Seventeenth Century , which was also translated into English in 1956 . Closer to the Dutch painting names - at least etymologically - is the u. a. term “banquet piece” used by Sam Segal. Sam Segal also makes a distinction between ontbijtje and banketje . Following his remarks, the banketje is simply a richer or larger variant of the ontbijtjes . Thus the ontbijtje corresponds to the representation of a breakfast or snack and the banketje corresponds to the representation of a feast. The contemporary inventories only partially prove such a clear differentiation. In the German art encyclopedias, monographs and overview works, terms such as “banquet piece”, “laid table”, “meal picture” or “breakfast still life” can be found.

Both banketje and ontbijtje , when used as a painting designation, are temporally neutral. The change in meaning of the word ontbijt , which in today's Dutch language means breakfast , probably caused confusion , but in the 17th century only referred to a small snack at any time of the day. Most likely the misleading description of the banketjes as breakfast still life arose from the anachronistic translation of ontbijtje or the unreflective translation of the English breakfast piece . Because this is also incorrect. The English breakfast never had the meaning of a meal (snack) independent of the time of day. It has always referred to the morning breaking of night fasting.

development

precursor

butcher's shop with an escape to Egypt scene in the background , 1551, oil on panel, 123 × 167 cm, Uppsala University's art collection

The market and kitchen items manufactured since the 16th century are regarded as the preliminary stage of the autonomous meal still life. Pieter Aertsen and his nephew Joachim Beuckelaer made works of art for secular buildings (town halls and private palaces). They are philosophical interpretations of the visible world, sometimes still with scenes from the history of salvation in the background - often a moral reference such as that to good household and life management through the scene of Christ in the house of Mary and Martha .

The paintings of the Aertsen workshop reflect the contemporary ambivalence between the joy of wealth and prosperity - expressed through the ostentatious presentation of victuals in the foreground - and the reflection on biblical religious values such as spiritual nourishment and temperance - expressed through the moralizing figurative representation in the background contrary. A corresponding example is Aertsen's painting from 1552 in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna . In the foreground it shows a still life consisting of several objects - including a particularly large piece of meat and the moralizing scene of Christ with Mary and Martha in the background. The pictorial motif established by Pieter Aertsen is present in art up to the early 17th century and influenced artists such as Vincenzo Campi , Lucas van Valckenborch and Georg Flegel . Also the so-called. Bodegones by Diego Velázquez go back to the Flemish and Italian models of Pieter Aertsen and Vincenzo Campi.

With the establishment of the autonomous meal still lifes that resulted from the richly laden market stalls and kitchen tables, the genre of market and kitchen items did not cease to exist, but continued to develop in parallel, as the paintings by Frans Snyders impressively demonstrate. In the process, these depictions of court kitchens and richly laden goods tables increasingly lost the moralizing or admonishing element. Paintings like Frans Snyder's fish market from approx. 1618–1620 in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna are no longer an expression of the conflict between luxury and morality, but evidence of the prosperity of the client or buyer and a very high level of artistic skill.

The emergence of the meal still life in the course of the independence of individual image motifs went hand in hand with a very specialized art production. There is evidence of a well-thought-out system of specialist painters in Flanders . This means that several artists made a painting, which consisted of different motifs. Each artist contributed the motif (animals, people, architecture, flower arrangements, arranged tables, etc.) which he was particularly good at. An example of this, although somewhat advanced in time, is the painting Madonna in a wreath of flowers . In this painting the impressive floral wreath is from Jan Brueghel the Elder. Ä. The figures in the picture are from a different artist - in this case from Peter Paul Rubens . A similar cooperation is the Holy Family of Jan Brueghel, who painted the impressive garland of fruit and flowers, and probably Pieter van Avont, who contributed the figures in the picture. Claus Grimm allows the entirely logical conclusion that the first early autonomous still lifes may only be parts of an unfinished, more complex work.

Joachim Beuckelaer

kitchen piece with the scene Jesus in the house of Maria and Martha in the background , 1566, oil on panel, 171 × 250 cm, Rijksmuseum , AmsterdamPieter Aertsen Vegetable

Stand with Saleswoman , 1567, oil on panel, 110 × 110 cm, State Museums , BerlinVincenzo Campi

Fruit Seller , ca.1580, oil on canvas, 145 × 215 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera , MilanPeter Paul Rubens & Jan Brueghel , Madonna in a wreath of flowers, ca.1619, Alte Pinakothek , Munich

Forms of meal still life

Flanders

Still Life with Cheese, Artichokes and Cherries , ca.1625, oil on panel, 46.7 × 33.3 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

At the beginning of the 17th century in Flanders, especially in Antwerp, the individual motifs of the Aertsen-Beuckelaer workshop definitely became independent pictorial themes. This first generation of still life painters in Flanders included Clara Peeters , who visited Amsterdam several times or even moved there, Osias Beert , Jacob van Es and Jacob van Hulsdonck . The specialization of these painters was not so advanced that they only painted banquets, but also still lifes with flowers , fish or fruit still lifes and combined them with one another.

The early Flemish banquetjes, in contrast to the Dutch ones, have a fairly close viewing point. The number of objects depicted on the table, including oysters, olives, fruits and baked goods as well as crockery made of metal and porcelain, is manageable. The composition is similar for all Flemish masters of the early banquet: a clear picture structure prevails, with the plates and bowls arranged symmetrically around a center. This emphasis on the surface is usually broken up by outstanding objects such as tall wine glasses, goblets or a tazza with biscuits. It is noticeable that the objects only allow a small amount of overlap. The individual plates and bowls are treated like individual studies and, thanks to the high point of view, are presented in an overview that overlooks the entire table. Osias Beert and his painter colleagues give the viewer an insight into the eating habits of the upper class through their still lifes. A distinctive feature of the Flemish banquet seems to be the presentation of the food and valuable objects on an uncovered stone table and the combination with flowers (in a vase).

In addition to goods that could be bought on the city market, the still lifes also show expensive imported groceries and, time and again, confectionery and confectionery. The preference of Flemish painters for the depiction of fine pastries and confectionery can be explained by their close ties to Spain as a stronghold of fine confectionery. Presumably such still lifes were also commissioned by Spanish buyers. In Osias Beert's paintings in particular, bowls with confectionery can be found alongside his typical oyster plate. Likewise with Clara Peeters, for whom v. a. the representation of unprepared fish, cheese and noble vessels such as the golden lidded goblet she often painted is characteristic. In Jacob van Hulsdonck's paintings, there is a clear contrast between expensive and cheap food, with the plate with the pork paws and the cut-up herring prepared for consumption as leitmotifs. For the Flemish still life painters active in the 1620s and 1630s, Frans Snyder's painting became the strongest influence. Frans Snyder's informal composition and increased color values became binding for the Flemish still lifes. Jacob van Hulsdonck's paintings also show this clear influence.

Clara Peeters

Still Life with Pastries and a Vase of Flowers , ca.1611, Museo del Prado , MadridFrans Snyder's

fish shop , 1616, Pushkin MuseumOsias Beert

Still Life with Oysters , ca.1610, oil on copper, 46.6 × 66 cm, Staatsgalerie , StuttgartJacob van Hulsdonck

still life with fish meal, pork paws a. a.

Holland

At the same time - at the beginning of the 17th century - pure still lifes were also created in the northern Netherlands. On the one hand, an influence by the Flemish still life painters cannot be ruled out, but on the other hand it should not be overrated either. It is known that after the fall of Antwerp (1585), numerous Flemings fled their Catholic homeland to the reformed north because of religious persecution or the hope of better working and living conditions. These immigrants brought not only capital and Flemish way of life, but also many years of professional experience and that sophisticated system of artistic production to their new home. So it is not surprising that artists like Nicolaes Gillis or Pieter Claesz , who were to bring the Banketje to full bloom in the following years, came from the southern Netherlands.

Haarlem display boards

In the northern Netherlands - especially in the city of Haarlem - Nicolaes Gillis and Floris van Dyck established this type of still life. There are also still lifes in the style of the Haarlem display boards by the two painters Floris van Schooten and Roelof Koets, who are also active in Haarlem. The reason for the Haarlem artists' special preference for these display boards and later for the small banquets cannot be clearly explained. Ingvar Bergström suspected that there might be a certain tradition of depicting set tables in Haarlem - an example of this is the portrait of a family by Maarten van Heemskerck in the picture gallery in Kassel , which was made before 1532 .

In terms of composition, her depictions of set tables are very similar to the Flemish meal still lifes by Osias Beert the Elder. Ä., Clara Peeters and Jacob van Hulsdonck. The treatment of the individual plates, bowls, jugs and glasses as individual studies modeled by light and shadow is also the same. The objects on the table are presented to the viewer as if in a "showcase". APA Vorenkamp therefore called these paintings in its investigation of Dutch still lifes "uitgestalde stillevens" ( uitstallen ndl. = To display , to display). Flemish and Dutch banquetjes also agree on the point that for the most part it is very exclusive and expensive items and food on the table. The dishes are made of imported Chinese porcelain , goldsmiths such as the cup screws, pewter dishes and also imported Venetian glasses . The fact that the rest of the population ate from wooden plates and drank from wooden cups at the time shows that the upper class set the table here.

But there are also clear differences to the Flemish still lifes. So the focus in the paintings by Gillis and Dyck is further away from the table being viewed. Objects can also be found on the Haarlem still lifes that the Flemish painter colleagues did not depict - for example the pyramid of cheeses stacked on top of each other, so typical of the Haarlem display boards. An equally striking feature is the table, which is decorated with a tablecloth and table runner made of damask . In contrast, the Flemish painting colleagues preferred a presentation of their fine dishes and valuable crockery on uncovered tables. A characteristic of the Haarlem meal still lifes is, in addition to the cheese, the often painted pewter plate with a sliced apple or a piece of melon that is pushed a little over the front edge of the table. Both Gillis and Dyck also had a particular fondness for nuts, which are scattered across the table in each of their paintings. Together with the other foods on the table (fruit, olives, fruits, etc.), these are all components of a dessert and not a main course.

Floris van Dyck

Still Life with Cheese, Fruit a. a. , 1613, oil on canvas, 49.5 × 77 cm, Frans-Hals-Museum , HaarlemFloris van Dyck

Still Life with Cheese , Fruit a. a., around 1615 , Rijksmuseum , AmsterdamNicolaes Gillis

Still Life with Cheese, Fruit a. a., approx. 1611, Frans-Hals-Museum , HaarlemFloris van Schooten

Still Life with Cheese , Von der Heydt Museum , Wuppertal

Monochrome banquets

→ Main article: Het Monochrome Banketje

In the 1620s and 1630s there was a drastic redesign of the meal still life. The Haarlem display boards were reduced to a few objects - sometimes even without a meal - with the typical color scheme determined by a basic color. Shifting the focus downwards is also an essential characteristic and creates more perspective in the still lifes and, in combination with the addition of signs of use, a changed effect in the sense of a "random snapshot". NRA Vroom examined this particular form of Dutch still life and named it "Het Monochrome Banketje". The main representatives of this special still life painting are Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz. Heda .

Pieter Claesz . Still life with oysters, Romans a. a. 1633, oil on panel, 38 × 53 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel

Willem Claesz. Heda , Still Life with Oysters , 1634, oil on panel, 43 × 57 cm, Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum , Rotterdam

Pieter Claesz .

Still life with herring, beer glass and bread roll , 1636, oil on wood, 36 × 49 cm, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen , Rotterdam

Amsterdam and Leiden

In Amsterdam in particular, there was an examination of the monochrome banquets of the Haarlem artists. Vroom referred especially to Paulus van den Bosch, Laurens Craen, Jan Jansz. van de Velde (III), Jan Jansz. the Uyl and his student Jan Jansz. Treck In addition to the Banketje, the Amsterdam artists mainly adopted the smoking still life , which Pieter Claesz only created in its purity.

Jan Jansz's paintings show independent qualities by far. the Uyl. This was not only based one-sided on the Haarlem meal still lifes, but also gave it such an impressive personal touch in its own implementation that innovations from his work had an effect on the painters working in Haarlem. That Jan Jansz. That Uyl was an artist with very independent qualities is also proven by the fact that in his painting he seems to anticipate the tendencies of the following generation of painters, e.g. Willem Kalfs .

Also Jan Davidsz de Heem seems to have (1625-1631) dealt with the Haarlem banketjes in his time in Leiden. At least the influence is from Jan Jansz. evident to the Uyls on the young Heem. Jan Davidsz. de Heem also painted arrangements reminiscent of the Dutch banquet in Antwerp, where he stayed from 1636 to 1664. In the years that followed, these were visibly adapted to the Flemish view of the image, which ultimately culminated in opulent and colorful, splendid still lifes from the 1740s.

Jan Jansz. den Uyl

Still Life with a Pewter Jug, Flute Glass and Römer , 1637, oil on panel, 83 × 69 cm, private collectionJan Jansz. Treck

Still Life with a Pewter Jug, Measuring Glass and Wanli Bowl , 1645, oil on panel , 67 × 51 cm, Museum of Fine Arts , BudapestStill life with a lobster and nautilus cup, 1634, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart , Stuttgart

Simon Luttichuy's

Still Life with Wine Glass (Snake Vase ) , around 1650–1660, oil on wood, 53.5 × 40.5 cm, Kunsthalle Hamburg

Germany

Generally speaking, the influence of Dutch artists was omnipresent in Europe in the 17th century. In the German-speaking countries, the set tables and representations of snacks by Peter Binoit , Gottfried von Wedig and Georg Flegel are noteworthy. All of them were directly or indirectly influenced by the Dutch meal still lifes.

As with contemporary flower painting, Georg Flegel stands out for its independent qualities. Georg Flegel was the first German painter to specialize in depicting food and dishes on a table, after having worked as a sculptor in the Linz workshop of the Dutch painter Lucas van Valckenborch . His paintings are inspired by the early Flemish banquetjes. In his still lifes, Flegel always reveals an image conception that is somewhat similar to that of his Dutch colleagues. In his last painting from 1638 he also presented the objects on the table from a high point of view. The painters of Banketjes in other countries had already overcome this successfully. But his paintings also have individual features. For example, he painted table utensils and food that were only available in Frankfurt am Main . He also integrated birds into his paintings and came up with innovative ideas such as a candlelit meal or arranging objects in an open cupboard. The colourfulness in some of his works from the 1930s can possibly be traced back to an orientation towards the clayey Dutch meal still lifes.

The meal still lifes of Peter Binoit , whose father emigrated from the Netherlands, are also reminiscent of the Flemish models. Similar to Osias Beert or Clara Peeters in his painting in the Galleria Sabauda in Turin, he painted a tazza with sugar cookies amidst other foods. But the Haarlem display boards must also have had an influence on him, because his two paintings in the Swedish National Museum and in the Louvre show characteristic features of this type of meal still life.

Another artist who made a name for himself as a painter of banketjes in Germany is Gottfried von Wedig from Cologne. His painting style was under the direct influence of Georg Flegel and the Flemish still life painters. He took over the idea of the meal illuminated by candlelight at night from Georg Flegel.

Unfortunately, little is known about Georg Hinz . Hinz probably established still life painting in Hamburg. His painting in the Hamburger Kunsthalle is not possible without knowledge of Dutch still lifes. On the one hand, a high focus and clear shadows point to early Flemish and Haarlem banquetjes. On the other hand, the ruffled tablecloth, the visible table edge and the portrait format show that the artist was dealing with the more mature, reduced Dutch snack pictures of the 1630s and 1640s.

Georg Flegel

Still life with roast, fish meal, wine etc. a. 1638, oil on copper, 29.5 × 46 cm, Václav Butta collectionGeorg Flegel

Still life with sugar cookies and a mouse by candlelight , oil on beech wood, 21.9 × 15.8 cm, private collectionPeter Binoit

Still Life with Pastries , ca.1615, Groninger Museum , GroningenGeorg Hinz

Still Life with Herring, Cheese, Bread and Beer , ca.1662, Hamburger Kunsthalle

Spain and Italy

The Old Cook , ca.1618, oil on canvas, 105 × 119 cm, Scottish National Gallery , Edinburgh

The meal still life is related to the content of the bodegones . The word, which means “poor tavern” in Spanish, developed into the generic term for the Spanish fruit and meal still lifes. What is meant here are all types of set tables, pantries, arrangements with meal items, dishes and utensils - with and without figures. The earliest bodegones are the still lifes by Juan Sánchez-Cotán. These are not representations of meals or ready-made dishes, but rather factual arrangements of various vegetables and occasionally dead animals. His signed and dated painting from 1602 in the Museo del Prado in Madrid shows various vegetables such as cardons , carrots and radishes, fruits such as lemon and apples and poultry in a stone niche . His paintings are not depictions of typical Spanish kitchens, but rather “mystically enhanced observation of nature”.

The more the genre painting attributable paintings by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez , which usually address the preparation of meals in kitchens, as Bodegones referred. However, these are not meal still lifes in the narrower sense - even if the still life-like arrangements are an essential part of these paintings. However, pure still lifes exist from his student Francisco de Palacios. In his paintings, the influence of his teacher's kitchen interiors is evident. As in Velázquez's paintings around 1620, the objects are depicted very factually and without excessive overlap. The application of paint with thicker brushstrokes also shows the influence of the later style of his teacher. The works of Francisco de Zurbarán also belong in this context, although he did not focus on the meal, but on individual fruits or vessels.

Juan van der Hamen y León is considered to be the “most important Spanish still life painter of the 17th century” . He was trained as a painter by his father from Brussels and had a large workshop in Madrid from 1622 to 1628. In his paintings, too, which emphasize the preciousness, the objects are treated in isolation. The tenebrismo used - an atmospheric chiaroscuro - as well as the depiction of the objects on stone pedestals of different heights, adopted by the Roman still life painters of Caravaggio's successors, is characteristic of Juan van der Hamen's painting . The visually appealing rendering of glass cups with their light reflections emerging from the dark was most likely taken over from his Flemish painter colleague Osias Beert the Elder . Ä.

Claus Grimm observed a characteristic development in Spanish still life painting, which led from a “rigid, partly symmetrical row of isolated vessels” to a “loose arrangement with overlaps and softer painterly transitions”. The latter can be seen in the works of the painter Luis Eugenio Meléndez , which also show neo-realistic tendencies - similar to the works of Chardin. In terms of content, the Spanish meal still lifes deal primarily with the presentation of desserts and confectionery - later, in the course of the return to rural, rustic values - also with rural meals. At no time did the meal still life in Spain experience such a clear differentiation as in Holland in the 17th century - the same applies to Italy and France.

The Italian and French examples of meal still life were created under the direct or indirect influence of the Dutch masters. During the 17th century, Italian painting in particular showed no real interest in the representations of opulent or modestly laid tables made in the north. In the 18th century, however, Christian Berentz, who worked in Rome, succeeded in establishing a "new type of elegant table setting" he had invented. The painter, who was born in Hamburg, was a student of Georg Hinz and trained through him in the Dutch flower and pompous still lifes. His painting in turn influenced artists such as Pietro Navarra, Maximilian Pfeiler and Gabriello Salci. The painters Giacomo Ceruti and Carlo Magini, who were also active in the 18th century, with their reduced, rustic-looking table settings, are in the sphere of influence of the innovations in still life painting based on Meléndez and Chardin.

Juan Sánchez Cotán

Still Life with Wild Birds, Vegetables and Fruits , 1602, oil on canvas, 68 × 89 cm, Museo del Prado , MadridJuan van der Hamen y León

Still Life with Pastries, Bowls and Glasses , 1622, oil on canvas, 52 × 88 cm, Museo del Prado , MadridFrancisco de Palacios

Still Life with Pastries , 1648, oil on canvas, 60 × 80 cm, Count Harrach's family collection, Rohrau Castle Picture GalleryLuis Eugenio Meléndez

Still Life with Salmon, Lemon and Vessels , mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 42 × 62 cm, Museo del Prado , Madrid

France

A notable French painter of the still life of meals is the Alsatian Sebastian Stoskopff . The son of Dutch emigrants was trained by Daniel Soreau in Hanau and worked in Venice, Paris, Strasbourg and Idstein. Stoskopff brought elements of Hanau painting to France, but also took up French influences - especially with regard to composition and coloring. He was in a mutually influencing relationship with the artists Lubin Baugin , Louise Moillon and Jacques Linard . Only a few pure meal still lifes are known from Sebastian Stoskopff. Most of his paintings are assigned to the splendid still life, with the reproduction of glasses being a specialty of Stoskopff. The painting in the Residenzgalerie in Salzburg, attributed to the painter, reflects most clearly the tendencies of the meal still life of the 17th century. The typical characteristics of the early Flemish banquets, which Stoskopff were probably conveyed through the Hanauer Kreis, can still be clearly identified. These merge in the painting with elements of contemporary French painting. The design of the space around the table is eye-catching, with a detailed cabinet and a shelf above the arrangement on which a box of chipboard lies.

In the 18th century, Alexandre-François Desportes again took up the subject of the meal still life as a French painter. However, these paintings only have formal similarities with the Dutch meal still lifes of the 17th century. Desportes' paintings, which in turn would be inconceivable without the works of Pieter van Boucle, have a purely decorative function. The Flemish-looking colors and relaxed composition can be derived from his Flemish teacher Nicasius Bernaerts, who in turn was a student of Frans Snyders .

The paintings by Jean Siméon Chardin and by artists who were influenced by him - such as the painter Anne Vallayer-Coster , for example , represent a rediscovery of the meal still life that emerged from the depiction of the everyday . These paintings have overcome the solidification in purely decorative values and show the meal as part of everyday life. Atmosphere and seriousness were more important to Chardin than baroque pomp and drama.

Sebastian Stoskopff

Still life with cheese, rolls and wine , 1st half of the 17th century, oil on canvas, 28.5 × 31.5 cm, Musée des beaux-arts André Malraux, Le HavreSebastian Stoskopff

Still Life with Pate and a Basket of Glasses , ca.1640, oil on canvas, 50 × 64 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg , StrasbourgLubin Baugin

The Dessert , mid-17th century, oil on panel, 52 × 40 cm, Musée du Louvre , ParisJean Siméon Chardin

Still Life with Brioche , 1763, oil on canvas, 47 × 56 cm, Musée du Louvre , Paris

Fictional display or real meal?

Group portrait of the Amsterdam Rifle Guild , 1533, oil on panel, 130 × 206.5 cm, Historical Museum, Amsterdam

A definitive statement as to whether the artists in the banquet of the 17th century painted actual meals or images of the wealth and household treasures only presented for viewing can only be assumed and cannot be clearly clarified by historical sources. The early Flemish banquets and the Haarlem display boards in particular pose a mystery in this regard. The designation as "display boards" or "special sideboard [...] for exclusive admiration" dictates the reading.

Most art historians reject an interpretation of the set tables depicted as depicting a festive buffet , as it could actually have been set up for the guests on the occasion of a celebration or a high-ranking visitor. If it is a question of the image of contemporary existing tables, then at most in their function as a purely representative sideboard or display board on the occasion of weddings, baptisms, professional anniversaries, etc.

The fact that there are not enough glasses, plates and cutlery on the tables for several guests speaks against the assumption that it could be a real banquet - just without the diners. The painters of such still lifes were familiar with the group portraits of the 16th century. These show how a table should have been set for several people. One of the numerous examples is the group portrait of the Amsterdam Rifle Guild from 1533 by the artist Cornelis Anthonisz. Here every diner has at least one of their own plates.

The sparsely set tables appearing in family portraits of the 16th century, which may have served as role models, also speak against the reading as images of real meals. The table in the foreground of Maerten van Heemskerck's family portrait from around 1532 is not the lunch table of the wealthy patrician family portrayed , but a “symbolic meal” as a sign of piety . The market and kitchen pieces by Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer, which are considered preliminary stages to the meal still lifes of the early 17th century, also fit into this context. These sumptuous combinations of different foods are just as far removed from reality as the symbolic meal in the family portrait.

Banquet in the house of Mayor Rockox , approx. 1630–1635, oil on oak, 62.3 × 96.5 cm, Alte Pinakothek , Munich

However, an interpretation of the Flemish banquets and Haarlem display boards as images of real festive buffets cannot definitely be ruled out. An indication that there is more reality hidden in the still lifes than assumed is the description of the preparation of the various foods themselves - i.e. apples in bowls, bread rolls on the plate, cherries and berries in small bowls, etc. It is reasonable to assume that at least these representations were derived from real festive tables. In addition, Sybille Ebert-Schifferer pointed out that the foods on the Haarlem display boards such as cheese, nuts and fruits were consumed as dessert. Something similar must apply to the Flemish banquets with their sugar cookies, oyster plates and fruit bowls. A plausible interpretation that does not contradict the symbolic reference to certain foods would be an interpretation of these tables in the sense of serving well-off citizens with delicacies provided for the guests - in the sense of finger food . This could also explain the “lack” of dishes. The painting by Frans Francken the Elder shows that this interpretation is possible. J. in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. In the painting from around 1630, which depicts the reception room of the Mayor of Antwerp Nicolaes Rockox, the guests courageously reach for the table set with oyster plates - certainly exaggeratedly lavish.

The image perception changed dramatically in the course of the 1920s and especially in the 1930s. The set tables no longer show different plates and bowls full of food, but only small - thematically arranged - arrangements. This theming according to individual motifs culminated in the monochrome Banketje . The clayey snack pictures by artists like Pieter Claesz. or Willem Claesz. Heda are determined by a respective main motif. This can be: the fruit pie, the plate with seafood (mainly oysters), a fish meal, a ham with a mustard pot or a roast. The symbolic references and the need for representation are still part of the picture's message. However, the painter no longer needed an abundance of plates and bowls bulging with various foods, but only a snack combined with a glass of wine or beer. The abstract display boards were transformed into “accidental snapshots” of spontaneous food intake.

These paintings are also works of the studio. This means that - as with the early banquetjes - no real meals were painted. But there is also no reason to deny that the artists had a real meal in front of their minds eye while composing the paintings. The thesis that the Banketjes or Ontbijtjes of the 20s, 30s and 40s of the 17th century represent meals as they existed in reality, support contemporary genre representations . A master of everyday observation was the painter Jan Steen , who ran an inn himself. His painting of a young woman offering oysters to the viewer from 1658 in the Mauritshuis shows an arrangement in the foreground consisting of an oyster plate, the associated pepper, a knife, a jug, a bread roll and a glass with wine. It is not possible to interpret this as a show buffet or a fictitious meal. The painting is an idea of the artist captured on canvas in order to convey certain content. But reality was copied for this purpose - with a real meal. Other main motifs of the 17th century meal still life, such as ham or pate, can also be found in the genre paintings.

From the still lifes of Jean Siméon Chardin and definitely from the still life as a test field for color modulations or emotional concepts in the 19th century, the question of whether the artist depicted real objects or situations is superfluous. With the still lifes in Realism , Impressionism or Expressionism , the representation of the real thing is a prerequisite. The meal still life is only found sporadically in these and the following styles.

Jan Steen

Girl with Oysters , c. 1658, oil on panel, 20.5 × 14.5 cm, Mauritshuis , The Hague

↓Esaias van de Velde

Happy company outdoors , 1615, oil on panel, 34.7 × 60.7 cm, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

↓Jan Steen

The Happy Family , 1668, oil on canvas, 110.5 × 141 cm, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

↓Pieter Claesz .

Still Life with Oysters , 1645, oil on panel, 62.2 × 48.3 cm, Saint Louis Art MuseumPieter Claesz .

Still Life with Turkey Pie , 1627, oil on panel, 132 × 75 cm, Rijksmuseum AmsterdamWillem Claesz. Heda

Still Life with Ham , 1635, oil on panel, 58 × 78 cm, Alte Pinakothek , Munich

literature

- reference books

- Abraham Bredius: artist inventories. Documents on the history of Dutch art in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1915, 7 volumes, register.

- Erika Gemar-Költzsch: Dutch still life painter in the 17th century. Luca-Verlag, Lingen 1995, ISBN 3-923641-41-9 .

- Fred G. Meijer, Adriaan van der Willigen: A dictionary of Dutch and Flemish still-life painters working in oils. 1525-1725. Primavera Press, Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-74310-85-0 .

- Monographs and exhibition catalogs

- Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century . Translated from the Swedish by Christina Hedström and Gerald Taylor. Faber & Faber, London 1956.

- Pieter Biesboer (among others): Pieter Claesz: (1596 / 7-1660), Meester van het stilleven in de Gouden Eeuw. (Aust.cat .: Frans-Halsmuseum Haarlem 2005). Uitgeverij Waanders BV, Zwolle 2004, ISBN 90-400-9005-X .

- Martina Brunner-Bulst: Pieter Claesz .: the main master of the Haarlemer still life in the 17th century. Critical oeuvre catalog. Luca-Verlag, Lingen 2004, ISBN 3-923641-22-2 .

- Andreas Burmester & Lars Raffelt & Konrad Renger & George Robinson & Susanne Wagini: Flemish Baroque Painting. Masterpieces from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. Hirmer, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7774-7030-9 .

- Pamela Hibbs Decoteau: Clara Peeters: 1594 - ca.1640, and the development of still-life painting in northern Europe. Luca-Verlag, Lingen 1992, ISBN 3-923641-38-9 .

- Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The history of the still life. Hirmer, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7774-7890-3 .

- HE van Gelder: W. Heda, A. van Beyeren, W. Kalf. Becht, Amsterdam 1941.

- Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. Belser, Stuttgart (inter alia) 1988, ISBN 3-7630-1945-6 .

- Eddy de Jongh (Ed.): Still-life in the age of Rembrandt. (Aust.cat .: Auckland City Art Gallery & National Art Gallery Wellington & Robert McDougall Art Gallery Christchurch 1982). Auckland City Art Gallery, Auckland 1982, ISBN 0-86463-101-4 .

- Eddy de Jongh (and others): Tot lering en vermaak: betekenissen van Hollandse genrevoorstellingen uit de zeventiende eeuw. (Aust.cat .: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam 1976). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1976.

- Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Ed.): Still life in Europe. (Aust.kat .: Westphalian State Museum for Art and Cultural History Münster & State Art Hall Baden-Baden 1980). Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe, Münster 1979.

- Koos Levy-Van Halm (Red.): De trots van Haarlem. Promotion van een stad in art en historie. (Aust.cat .: Frans Halsmuseum Haarlem & Teylers Museum Haarlem 1995). Haarlem (et al.) 1995.

- Michael North: History of the Netherlands. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-41878-3 .

- Simon Schama: Overvloed en onbehagen: de Nederlandse cultuur in de Gouden Eeuw. Translated from the English by Eugène Dabekaussen, Barbara de Lange en Tilly Maters. Contact, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-254-6838-1 .

- Norbert Schneider: Still life. Reality and symbolism of things. The still life painting of the early modern period. Taschen, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-8228-0398-7 .

- Sam Segal, William B. Jordan: A prosperous past. The sumptuous still life in the Netherlands. 1600-1700. (Aust.cat .: Delft & Cambridge & Massachusetts & Texas). SDU Publ., The Hague 1989, ISBN 90-12-06238-1 .

- Sam Segal: Jan Davidsz. de Heem en zijn kring. (Aust.cat .: Utrecht & Braunschweig 1991). SDU Publ., Utrecht 1991, ISBN 90-12-06661-1 .

- APA Vorenkamp: Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van het Hollandsch stilleven in de 17 eeuw: proefschrift the Verkrijging van den graad van doctor in de letteren en wijsbegeerte aan de Rijks-Universiteit te Leiden. NV Leidsche Uitgeversmaatschappij, Leiden 1933.

- NRA Vroom: A modest message as intimated by the painters of the "Monochrome banketje" . Vol. 1 & 2: Interbook International, Schiedam 1980, Vol.3: Wilson DMK, Nuremberg 1999.

- NRA Vroom: De Schilders Van Het Monochrome Banketje. Kosmos, Amsterdam 1945.

- Essays and Articles

- Pieter de Boer: Jan Jansz. the Uyl. In: Oud Holland. 57, 1940, pp. 48-64.

- Claus Grimm: Kitchen pieces - Market pictures - Fish still life. In: Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Hrsg.): Still life in Europe. (Aust.kat .: Westphalian State Museum for Art and Cultural History Münster & State Art Hall Baden-Baden 1980). Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Münster 1979, pp. 351–378.

- Eddy de Jongh: De interpretatie van stillevens: boundaries en mogelijkheden. In: Eddy de Jongh: Kwesties van betekenis. Subject en motief in de Nederlandse schilderkunst van de zeventiende eeuw. Primavera Pers, Leiden 1995, ISBN 90-74310-14-1 , pp. 130-148.

- Wouter Th. Kloek: The migration from the South to the North. In: Ger Lujten (Ed.): Dawn of the Golden Age. Northern Netherlandish art 1580-1620. (Aust.cat .: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 1993/94). Waanders, Zwolle 1993.

- Joseph Lammers: Fasting and Enjoyment. The set table as a theme of still life. In: Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Hrsg.): Still life in Europe. (Aust.kat .: Westphalian State Museum for Art and Cultural History Münster & State Art Hall Baden-Baden 1980). Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Münster 1979, pp. 402-429.

- Fred G. Meijer: Breakfast still life and monochrome banketjes. In: Kunst & Antiquitäten 1–2 (1993), pp. 19–23.

Web links

Notes and individual references

- ↑ APA Vorenkamp: bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van het Hollandsch stilleven in de 17 eeuw. 1933, p. 6ff.

- ^ Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century. 1956, pp. 98ff & 112ff.

- ↑ Sam Segal, William B. Jordan: A prosperous past. 1989.

-

^ "[...] early 17th-century still lifes with tables set for a meal - banketjes (banquet pieces) and ontbijtjes (breakfast pieces). The banketje is simply a richer form of the breakfast piece. ”

Sam Segal, William B. Jordan: A prosperous past. 1989, p. 28. -

↑ On the basis of the artist inventories published by Bredius, it should be noted that the term ontbijt (with its variants) occurs only very sporadically. The term banket (in different variations) is represented far more often. Repeatedly in the inventories depictions of gods gathered at a banquet table are referred to as gods banquets. In addition, there is also a list of dessert still lifes and small arrangements as a banquet. The diminutive seems to have been but binding in these cases.

See: Abraham Bredius: Artist Inventories. 1915. - ↑ a b c d e f Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 81.

- ↑ Norbert Schneider: Still life. Reality and symbolism of things. The still life painting of the early modern period. 1989, p. 101.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 118.

- ^ Gerhard Strauss, Harald Olbrich: Lexicon of Art. Volume 7, 1994, p. 64.

-

↑ “Een lichte maaltijd, op welk oogenblik van den dag ook; forg. hd. snack. “

Matthias de Vries: Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal. Volume 11, Nijhoff, Leiden 1993, p. 1811.

See also: Jan de Vries: Nederlands Etymologische Woordenboek. Koninklijke Brill, Leiden 1997, p. 486. -

↑ Bredius may have laid the foundation for the wrong terminology in his artist inventories. At least he translated just as wrongly:

"Een ontbytie (Still life from a breakfast table [sic]) sonder lyst van Pieter Claesz."

Abraham Bredius. Artist inventories. Volume 1, 1915, p. 5. -

↑ “1472 'brekefaste'; earlier variant of 'breffast' (1463), from the earlier verb phrase 'breken faste' […], in reference to 'break' and 'fast', in the sense of ending one's fast of the night before. "

Robert K. Barhhart (Ed.): Chambers Dictionary of Etymology. Chambers, Edinburgh et al. a. 2006, p. 115. - ↑ Claus Grimm: kitchen pieces - market pictures - fish still life. In: Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Hrsg.): Still life in Europe. 1979, pp. 351-378.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters . 1988, p. 28.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 43.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life . 1998, p. 43ff & Claus Grimm: Stilleben. The Dutch and German masters . 1988, p. 30.

- ↑ The painting Fischmarkt is a collaboration between Frans Snyders and Anthonis van Dyck , who contributed the figures in the background.

- ↑ Andreas Burmester u. a .: Flemish baroque painting. (1996), p. 92.

-

↑ Andreas Burmester u. a .: Flemish baroque painting. (1996), p. 50.

Figure: Holy Family by Jan Brueghel the Elder. Ä. - ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 73.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: kitchen pieces - market pictures - fish still life. In: Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Hrsg.): Still life in Europe. 1979, p. 370.

-

↑ Pamela Hibbs Decoteau: Clara Peeters. 1992, p. 90.

Fred Meijer, however, doubts that it is Clara Peeters, the painter. See: Fred G. Meijer: Still Life paintings from the Netherlands. In: Oud Holland. 114, 2000, p. 232 & Fred G. Meijer: The Ashmolean Museum Oxford. 2003, cat.no.62. - ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 115.

-

^ "The bare table and inclusion of flowers suggests a contact with Flemish art."

Pamela Hibbs Decoteau: Clara Peeters. 1992, p. 92. -

↑ Norbert Schneider dedicated a separate chapter in his book to these special still lifes: “Dessert and confectionery still life”

In: Norbert Schneider: Stilleben. (1989), pp. 89ff. - ↑ a b c Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 118.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 104.

-

^ "Within a very short span of time, specialization introduced genres to the standard painter's repertoire previously unexplored in painting of the northern provinces. Until 1585, hardly any landscapes, city views, or scenes from everyday life had been painted in the northern netherlands, no land or sea battles, or still lifes. The extraordinarily successful development of numerous new genres after 1600, genres that had not all initially been developed in the south, was primarily the immigrants' doing. "

Wouter Th. Kloek: The migration from the South to the North. In: Ger Lujten (Ed.): Dawn of the Golden Age. 1993, p. 58. - ↑ See: Roelof Koets: Still life with fruit, cheese, drinking vessels, etc. a. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. & Floris van Schooten: Still life with jug, shrimp and cheese ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

-

↑ “It was mentioned in the introduction that academicians and genre painters at Haarlem showed a great predilection for arranging the figures they painted round a laid table. Heemskerck can be cited as an example; the many group portraits of volunteers round a table should also be mentioned. In Haarlem there was thus a certain tradition in this field which may have favored the development of breakfast-piece. "

Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century. 1956, p. 100, note 7 (= p. 303). - ↑ APA Vorenkamp: bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van het Hollandsch stilleven in de 17 eeuw. (1933), p. 24f.

- ↑ Lammers, Joseph: Fasting and Enjoyment. The set table as a theme of still life. 1979, p. 424.

- ↑ Pamela Hibbs Decoteau: Clara Peeters. 1992, p. 92.

- ↑ Sibylle Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 90.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 83.

-

^ NRA Vroom: De Schilders Van Het Monochrome Banketje. Kosmos, Amsterdam 1945.

In English and with some additions: NRA Vroom: A modest message as intimated by the painters of the “Monochrome banketje”. Vol. 1 & 2: Interbook International, Schiedam 1980, Vol.3: Wilson DMK, Nuremberg 1999. - ↑ About Paulus van den Bosch ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the RKD.

- ↑ About Laurens Craen ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the RKD.

- ↑ Jan Jansz. van de Velde was born and educated in Haarlem, but lived in Amsterdam for a long time. About Jan Jansz. van de Velde ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the RKD.

- ↑ About Jan Jansz. Trek ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the RKD.

- ^ NRA Vroom: De Schilders Van Het Monochrome Banketje. 1945, p. 108 ff.

- ^ Martina Brunner-Bulst: Pieter Claesz. (2004), p. 173.

- ^ Pieter de Boer: Jan Jansz. the Uyl. In: Oud Holland. 57, 1940, p. 51.

-

↑ "The style of the Dutch fine painters radiated especially in Northern Europe, as the painters' purchases and stays abroad testify [...]."

Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 78. - ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Christian Klemm: World Interpretation - Allegories and Symbols in Still Life. In: Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (Hrsg.): Still life in Europe. 1979, p. 153.

- ^ Gerhard Langemeyer, Hans-Albert Peeters (ed.): Still life in Europe. 1979, Cat. No. 222, p. 561.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 120ff.

- ^ Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century . 1956, pp. 98-111.

- ↑ a b c Sibylle Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 122.

- ↑ Fred G. Meijer, Adriaan van der Willigen: A dictionary of Dutch and Flemish still-life painters working in oils. (2003), p. 38.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 209.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Dutch and German masters. 1988, p. 78.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 162.

- ↑ Wolf Stadler et al. a .: Lexicon of Art. Volume 2, 1994, p. 218.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 163.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 147.

- ↑ Juan van der Hamen y León ( Memento of the original from May 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

- ↑ a b c Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 139.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 181.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 222.

- ↑ About Christian Berentz ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the RKD.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, pp. 208f.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 218.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 19.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 229.

- ↑ Still life with pastries, fruits and cheese basket at www.lib-art.com.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: Still life. The Italian, Spanish and French masters. 1995, p. 246.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 196.

- ^ Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century. 1956, p. 100, note 7 (= p. 303).

- ^ Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century. 1956, p. 12.

- ↑ Claus Grimm: kitchen pieces - market pictures - fish still life. 1979, p. 360.

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: The story of the still life. 1998, p. 90.

- ↑ Banquet in the house of Mayor Rockox ( Memento of the original from January 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. in the database of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

- ^ Fred G. Meijer: Breakfast Still Life and Monochrome Banquet. 1993, p. 23.

- ↑ Wolf Stadler et al. a .: Lexicon of Art. Volume 11, 1994, p. 172.

- ^ Gerhard Strauss, Harald Olbrich: Lexicon of Art. Volume 7, 1994, p. 66.

-

^ Tarte aux pommes (1882) by Claude Monet

Coffee, Milk and Potatoes (around 1896) by Albert Anker