Orienteering

Orienteering , mostly short OL called, is a running sport . In the area several are checkpoints set with the help of map and compass must be found. The runner chooses the route that is optimal for him . As a result, orienteering requires not only physical fitness but also a high level of mental performance. Orienteering developed at the beginning of the 20th century in Scandinavia , where it is now a popular sport. Orienteering is practiced worldwide today.

International orienteering is organized in the International Orienteering Federation (IOF) with currently 76 member countries (as of March 2020). Orienteering is one of the sports recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) , but has not yet been played at the Olympic Games . In addition to the classic orienteering, there are numerous variants of the sport, such as mountain bike orienteering and ski orienteering . Since most types of orienteering take place in near-natural areas, the ecological effects of competitions are also controversial.

Basics

The basic aim of orienteering is to pass control points in the terrain as quickly as possible in a fixed order. The runner is generally completely free to choose the route to run between the individual checkpoints, which are called posts . A map and a compass are only available to every athlete to help them find the best possible running route; other technical aids are prohibited. Orienteering races are usually held in natural terrain, especially in the forest, but relatively well-developed areas such as parks are also suitable for sports. Since, to a large extent, people also run away from the paths, orienteering is usually not very attractive as a spectator sport.

Practical implementation

Before the start, the orienteer usually has little information available besides the general nature of the terrain, in particular the length of the route (measured as the crow flies ) and the meters in altitude to be completed (minimum gradient on an assumed optimal route). In addition, he is aware of the number and description of the checkpoints as well as any mandatory stretches to be completed. The card is usually only given to the athlete immediately before the start. The items to be approached are printed on it in the specified order, the so-called path . The completion of the positions in the prescribed order is checked by the control systems carried along , now mostly electronic devices.

A fundamental problem with orienteering is to ensure the same conditions for all participants as much as possible. In particular, it is important to prevent a simple run-on and to ensure that all runners orientate themselves independently. For this reason there is usually no mass start at the orienteering. Rather, the competitors start individually at intervals of two to five minutes, so that each runner is on his own as far as possible. In addition, a large number of different tracks for individual categories (gender, age and performance classes) are offered at orienteering events . This means that the number of participants per category is not too high, the participants are more widely distributed in the area and the benefit of running behind is further reduced. Several thousand athletes of different age and ability classes with adequate lengths can take part in large orienteering events.

In order to create the same conditions for all participants, only areas that have not been used for a long time and new maps are used for competitions. Entering the running area before the competition is prohibited.

The length of the lanes to be completed can vary greatly depending on the competition. In official World Cup races and title fights according to the standards of the International Orienteering Federation (IOF), for example, the track lengths are chosen so that the winning times are between 12 and 15 minutes in the sprint and up to 100 minutes in the long distance discipline ; But there are also much longer orienteering runs. The specific distances and inclines covered in a certain time can vary greatly depending on the nature of the terrain and the difficulty of the orientation tasks. For example, the distance (as the crow flies) in the long distance for men is usually around 10 to 15 kilometers.

equipment

Orienteering map

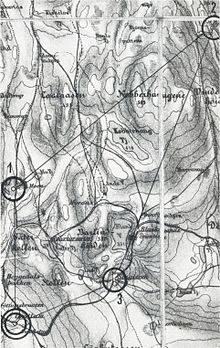

The map is the most important aid for orienteering. Nowadays, specially made orienteering maps are mostly used, which differ from conventional topographical maps by their higher level of detail. They therefore represent the terrain on a particularly large scale , according to the IOF regulations 1: 10,000 or 1: 15,000, and for sprints up to 1: 4,000. The equidistance , i.e. the vertical distance between two contour lines , is usually five meters, or two and a half in particularly flat terrain. Orienteering maps are particularly accurate, so even very small objects are shown, for example rocks one meter in size. In addition to accuracy and legibility, the presentation of the walkability of the terrain is particularly important. The signatures specified by the IOF therefore differ greatly from commercially available topographic maps. For example, forest is represented by white color, while green tones denote thickets that are differently difficult to penetrate .

The path to be covered is printed in red on the map (start, post and destination, connected in running order by straight line) and additional competition-related information such as refreshment and medical posts and any restricted areas or mandatory routes.

compass

After the map, the compass is the most important guide. Usually, special orienteering compasses are used for orienteering , which are easy and quick to use. The compass is used on the one hand for northing , i.e. for correct alignment of the map, and on the other hand for finding the desired point. This technique is particularly used when the terrain is very poorly structured and offers few clues that can be recognized on the map. However, extremely structured and detailed terrain with a vast amount of information can also be a reason for increased use of the compass. The most common is a combination of map and compass orientation. With the increasing accuracy of the map material since the beginnings of orienteering, the compass has tended to lose importance compared to the map.

Item description

The control description, which is usually issued before the start, is a small piece of paper that contains additional information on the control in the form of standardized symbols. The item description is intended to enable the item to be clearly identified and therefore contains, in addition to a control number, a description of the exact location of the item in the control room as well as any additional information (e.g. catering items). In addition, general information such as track length, vertical meters to be completed or the length of compulsory routes are given.

Control system

Post control systems must be carried in order to prove the completion of the control post . While control cards were used for a long time , which had to be marked with individual patterns using punch pliers attached to the post , electronic systems ( SportIdent , EMIT ) predominate today . A chip worn by the runner is electronically marked at the post location.

Clothing and footwear

Many runners run with orienteering shoes specially made for orienteering . These are light and sturdy shoes with hard soles, often with short steel spikes (“Dobb spikes”) to increase slip resistance. There are low models and those that reach over the ankle. In addition to shoes, gaiters or reinforced stockings are often used to protect the shins from injuries caused by vegetation.

The clothing is relatively irrelevant, but should be tear-resistant and water-permeable. Special orienteering suits are usually made of polyamide or similar materials that protect against injuries caused by nettles, thorns or branches.

Forms of competition, variants and related sports

Apart from the individual competition, the relay orienteering run and the team orienteering run are mainly important in orienteering . In the relay race, a relay, which usually consists of three to five, but also more runners, conquers different routes one after the other. In contrast to the individual run, such competitions are usually held with a mass start, since the problem of running behind can be avoided here by differently ranking the sections of the route to be covered by the individual runners.

In team races, a team usually consists of three to four runners. These start together, but then split up in order to process the required items without a fixed order. There may be compulsory posts for all team members, but also those that only one participant has to achieve. Since only the running-in time of the last runner of a team decides on the placement, the team strategy is particularly important when dividing the tasks.

There are also numerous variants of orienteering, which are mainly used as training methods, but only rarely as a competition format. These include, for example, runs with "reduced maps", i.e. maps that do not contain any paths that only consist of the contour lines ("contour lines-OL"), or in which only a narrow strip along the straight line ("corridor OL") or small areas around the posts are visible ("window OL"). An extreme form of reduced map is the “compass-blind flight”, in which the map contains no information except for the position of the posts and in which one only has to orientate oneself with the compass. In the "memory orienteering", the runner only has a small map section available at the post locations, which extends to the next post, so that he has to memorize the entire route.

The night orienteering , which involves running in the dark with a flashlight or headlamp , is particularly demanding in terms of orientation. In some countries championships of this special form are held. The score orienteering , in which as many items as possible (often of different values) have to be "collected" in any order in a given time, is often used as a training form in Europe, whereas in Australia it is in its extreme form, the up to 24 Rogaining for hours , also popular as a competition. In Europe, on the other hand, extremely long orienteering runs are usually held in the conventional form with a fixed sequence of posts. Such competitions, which often take place in the high mountains , sometimes extend over several days, with overnight equipment having to be carried in a backpack. Usually you don't run here individually, but in pairs or in teams. Another special feature are orienteering runs in the city area. The best known example is the annual city orienteering in the streets of Venice .

Orientation marches take place in a similar form in the military sector as part of combat training.

Orientation sports can also be practiced with the help of other means of transport. The IOF organizes traditional ski orienteering , mountain bike orienteering , which has been gaining in importance since the 1980s, and trail orienteering , a variant of orienteering that can also be practiced by athletes with disabilities . Orientation sports can, however, also be practiced by boat in the appropriate environment; competitions in orientation diving and orientation riding are also known . In sports hitchhiking, the participants hitchhike between the posts, usually in any order.

The haik is a type of orienteering that comes from the Swedish scout movement.

A sport related to orienteering with a focus on technical support is amateur radio direction finding , in which the guards are equipped with radio transmitters. The Fox Oring is a variant of amateur radio pinpointing with greater emphasis on the orienteering component. Geocaching is based on orientation with the help of satellite navigation systems , in which the competition aspect plays a subordinate role.

Orienteering from a sports science perspective

Physical factors

Sports scientists characterize orienteering as a long-distance run with micro-breaks, i.e. short interruptions that are created by marking the posts and running breaks for the purpose of orientation. In this respect, the OL is similar to an interval run . The amount of time these interruptions take varies greatly depending on the level, the nature of the terrain and the difficulty of the orientation requirements. It can be 10% of the total running time for hobby runners, but significantly less for top runners and in easy-to-run terrain. Elite runners can, for the most part, manage map reading and orientation without stopping even in untracked terrain . The time spent on orientation tasks can increase dramatically when errors occur.

Orienteering clearly differs from long-distance running on the track or on the road in terms of the demands placed on the runner by the changing ground conditions and different, sometimes difficult to walk on or steep terrain. Running on soft ground (moss, swamp, sand) requires significantly more energy than walking. A continuous running rhythm can hardly be maintained when running in the forest. For example, obstacles often have to be jumped over, breaks for orientation taken or the pace adapted to the terrain. The heart rate and lactate values of orienteering runners therefore reach a higher level and fluctuate more strongly in different competition sections and different types of terrain than in other endurance sports.

In this respect, muscle strength ( endurance and high speed strength ), mobility and coordination are particularly stressed during orienteering . The distribution of the individual condition factors is assumed to be around 70% endurance, 15% strength endurance, 10% speed strength and 5% coordination, depending on the running terrain and route. Characteristic of the running style in OL are high elevation of the knees, frequent quick changes of direction and irregular changes in step frequency and length. The importance of running technique compared to physical fitness factors is significantly higher than that of road running. In general, orienteering is aerobic , but top athletes sometimes also achieve anaerobic stress.

Running times and speed in orienteering are therefore hardly comparable with other sports. Even good runners need 5 to 6 minutes per kilometer in open forest terrain, in dense thickets this number can increase to over 25 minutes per kilometer, or the speed can drop to below 20% of the speed achieved in the forest. In addition, it should be noted that in the orienteering, the real distance covered can be up to 40% longer than the specified track length based on the linear distance between the individual posts. In addition, the altitude to be covered must be taken into account. Gradients of up to 4% of the running route are common in orienteering. Up to 7% is possible in steep terrain; Here too, however, it must be borne in mind that the altitude meters actually covered can be significantly higher than what is assumed on a hypothetical ideal route.

Psychological factors

Orienteering is a sport that not only places physical demands on people but also high demands on the mind. In addition to the competitive tactics that are comparable to other running sports, correct and quick map reading and route planning are of decisive importance. Important here are cognitive services such as the quick recognition and implementation of the map information in a mental representation , the recognition of possible running routes and the decision on an optimal route. This also includes good strategic planning of the respective procedure, such as the use of adequate orientation techniques in different phases of approaching the post (e.g. subdivision into sub-sections, different investment in precision in phases of "rough" and "fine orientation") . Good memory is important in order to minimize the frequency of interruptions or slowdowns for orientation purposes. While running, the map and the terrain are often compared with one another in order to be sure of your own position. Finding your own position on the map is particularly challenging if the runner discovers, due to discrepancies, that it does not correspond to the previously assumed position.

A high level of concentration is particularly important in orienteering , which must be maintained for a long time even under physical stress. In the course of comparing the map and the terrain, attention must alternately be directed to the map and nature and in some moments reach a high level of intensity, while it can decrease to a significantly lower level during long runs in easy terrain.

Orientation and running performance are closely interrelated in orienteering: Orientation errors result in longer running distances, and fatigue in turn leads to an increased incidence of orientation errors. Running to the limit of your physical exertion can therefore be counterproductive in some situations. The situation-appropriate choice of running speed is just as important as the weighing of alternatives with regard to different orientation techniques and routes in order to be able to maintain a balance between orientation work and running factors. In this respect, there is often no objective ideal route, rather every runner has to try to choose the route that is optimal for him in his or her condition.

Risk of injury

The vast majority of injuries during orienteering involve the lower extremities. Overall, over 90% of all orienteering injuries occur in the area below the knee. The focus here is on sprains (almost a third of all injuries), abrasions (about a quarter), ligament injuries , broken bones and bruises . The ankle joint is particularly often affected. Muscle strains usually occur in the thigh area. The main reasons for injuries in the course of the orienteering are overload, twisting ankle and falling. Accidents often happen in difficult terrain, such as stony, steep terrain rich in fallen wood, and in bad weather. Orienteers often use tape bandages to prevent ligament tears . Reinforced stockings or gaiters are worn as protection against shin injuries.

Since wounds often become very dirty when falling in nature, there is a risk of tetanus infection or sepsis . Cases of hepatitis B infections from scratches and abrasions that are common in OL are also known. In some regions, tick bites can carry the risk of early summer meningoencephalitis or other infectious diseases (e.g. borreliosis ). In some areas, snakebites can be dangerous.

Orienteering and the environment

Orienteering and its effects sometimes lead to conflicts with the interests of nature conservation as well as with other forest users such as hunters, foresters, forest owners and farmers. In order to reduce the impact on the environment and conflicts with other interest groups as much as possible, extensive planning measures to minimize damage are common today, especially at larger events. For example, when the course is being laid, quiet zones are planned for the game , which should offer the animals a refuge. Greater consideration for the animal world is necessary, especially at the time of setting . Zones that are particularly worthy of protection can also be marked as restricted areas for runners. Fields often have to be crossed on prescribed mowed compulsory stretches in order to avoid damage to the vegetation. Large competitions with many participants should only take place in an area at longer intervals (several years) in order to give the vegetation the opportunity to regenerate. The use of spiked shoes may be restricted or prohibited in certain regions. Regulations and recommendations on environmental issues are drawn up by the IOF's environmental commission.

Permanent damage to nature due to walking in the forest does not usually occur if the relevant guidelines are observed. Nevertheless, orienteering is subject to increasingly strict regulations in many countries, with reference to possible damage to nature. Obtaining permits to host large runs generally becomes more difficult.

Elite sport

In the history of the sport, outstanding orienteering athletes came mainly from the Scandinavian countries of Sweden , Norway and Finland . B. the seven-time world champion Øyvin Thon from Norway, the Swedish double world champion Jörgen Mårtensson , the Swedish double world champion Ulla Lindkvist or the Swedish three-time world champion Annichen Kringstad . Well-known non-Scandinavian athletes are Thierry Gueorgiou from France as well as the multiple world champion Daniel Hubmann and the 23-time record world champion Simone Niggli , both from Switzerland .

The most important competitions of the year are the orienteering world championships (WOC for short). From 1966 onwards, the WOC has been held every two years, and has been held annually since 2003. Since 2001 there have been three course lengths at world championships (sprint, middle distance, long), before that there was only one world champion for men and women. The traditional relay race is viewed by many nations (especially the Scandinavian countries) as the most important competition in the world championships. Student World Championships (WUOC) and Army World Championships (CISM) are also held.

In addition to the World Championships, the European Orienteering Championships (EOC) are held, where competition is often more intense than at World Championships, as several runners from the top nations are eligible to start. The Orienteering World Cup takes place throughout the year, the final ranking of which is made up of the results of the individual world ranking events at the end of the year.

Since orienteering has not yet been included in the program of the Olympic Games, the World Games are the most important multisport event at which orienteering races are held.

For young orienteers, the most important international competitions are the Junior World Championships (JWOC), the Youth European Championships (EYOC) and the Junior European Cup (JEC).

The Park World Tour (PWT for short) is also popular , with sprint orienteering races close to the city, especially in park areas. This should make the sport, which is otherwise difficult to watch for the public, also more attractive for live viewers and television broadcasts. Another innovation to counteract the shortcoming of poor publicity are electronic systems that enable the runners to be tracked on a map in real time on a monitor.

Popular sport

Orienteering is a sport with a comparatively low number of spectators and high numbers of participants. The financial resources of the extremely organization-intensive sport are limited, which is due, among other things, to the poor media suitability and advertising effectiveness of running in natural terrain. On the other hand, orienteering races offer competition opportunities for participants of all ages. Owing to the widespread system of dividing runners into competitions according to age and performance classes and offering adequate route lengths, OL is seen as a particularly family-friendly sport. At major events, routes for age groups between 10 and 95 years are offered. Multi-day runs with three to six stages, in which several thousand athletes often take part, are particularly popular.

Orienteering is still popular today, especially in the Scandinavian countries, where orienteering is considered a national sport. Orienteering is taught in schools and the largest orienteering events take place here. The highest number of participants is usually found in the annual Swedish five-day O-ring run , in which up to 25,000 runners start. The largest relay races are also held in Scandinavia, such as the Swedish Tiomila and the Finnish Jukola , where usually over 10,000 participants start.

In Central Europe, Switzerland is an important center for orienteering. The triple election of Simone Niggli as Swiss Sportswoman of the Year (2003, 2005 and 2007) shows the popularity of the OL. In some cantons, orienteering is part of the school sports program. In Germany and Austria, however, orienteering is far less common. Outside of Europe, orienteering is particularly popular in Australia , New Zealand and Brazil . The number of orienteers around the world is not exactly known, at least there are several hundred thousand athletes.

history

As early as 1817, Johann Christoph Friedrich GutsMuths suggested orientation exercises for the sons of the fatherland in his gymnastics book as part of the military sports education of young people, but this idea was hardly heard. In the further course of the 19th century there were various approaches to combine orientation and sport, which were also founded in the military environment. So-called “scouting exercises”, as they were practiced in northern Europe in the middle of the 19th century, were increasingly carried out with a sporting background and also included orientation tasks to varying degrees. In Scandinavia, particularly Norway, maps were used in military cross-country skiing training in the late 19th century . Most of these early forms of orienteering took place in winter. However, the so-called "foot orienteering" was increasingly being practiced as a form of training for ski orienteering, starting in Sweden. The first public competitions are known from Norway from 1897. On May 13, 1897, a run is said to have been held near Bergen . The first well-known run took place near Oslo on October 31, 1897: eight runners set out on a 10.5-kilometer route with three set posts, with the winner covering the distance in 1:41:07 h . The scale of the map was 1: 30,000 and the equidistance was 20 meters. In addition, ski orienteering also flourished: the first relay competition took place in Sweden in 1900, and Swedish championships were held as early as 1910.

Although the sport began to detach itself from its military environment at this time, today Major Ernst Killander , a Swedish scout functionary , is mostly seen as the inventor of civil orienteering. From 1913 onwards, he recognized that young people were becoming less interested in athletics and tried to make training more diverse by moving running to nature and additional orientation tasks. The first smaller races were a great success and so on March 25, 1919 the first larger competition was held with 155, according to other sources 220 participants. A monument about 15 kilometers south of Stockholm marks the venue of this run as the birthplace of orienteering. The first local championships were held in Sweden as early as 1922. Orienteering quickly developed into a popular sport. The first orienteering club was founded in 1928 with the Swedish SK Gothia , and in 1932 the first international competition took place between Norway and Sweden. At that time, the runners had only very inaccurate, small-scale maps available, which is why the early orienteering races were rather challenging in terms of runners. In the 1930s the quality of the compasses and the Swedish maps improved considerably and the orientation component became increasingly important.

In 1937 the first national championships took place in Sweden and Norway. In 1938, the Svenska Orienteringforbundet (SOFT) was the first national orienteering association. At that time, SOFT, which was dominated by members of the scouting movement, stood in contrast to the ski association, which organized competitions in ski orienteering independently. Orienteering received a lot of support from the Swedish government and was soon made compulsory in Swedish schools, where it is still taught today.

From around 1930 the orienteering became popular in Finland as well. In Central Europe, Switzerland and Hungary, where the first races have been held since the 1930s, were among the pioneers, and Denmark followed shortly afterwards . In Switzerland, orienteering experienced a great boom during the Second World War , with the idea of physical training again coming to the fore in the course of the preliminary lessons and orienteering being seen as part of military training. The National Socialists in Germany also promoted orienteering. The slow spread of sport in Germany after the Second World War is attributed to the association of the orienteering with this paramilitary background. The German Orienteering Championships have been held since 1963 .

In 1946 the first international orienteering association was founded with NORD (Nordisk Orienteringsrat), which encompasses the Scandinavian countries. In the same year the first orienteering took place in the USA . In Central and Eastern Europe, too, there was a popularization in the following period; Orienteering was introduced in Czechoslovakia , the GDR , Bulgaria and Yugoslavia . Furthermore, the years after the Second World War were characterized by professionalization, especially in the field of maps, so in 1948 a map created entirely for orienteering purposes was used for the first time in Norway, the first colored map followed in 1950.

In 1959, the International Orientation Sports Conference, organized by NORD, took place in Sweden, in which, in addition to the Scandinavian countries, Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the FRG , the GDR, Yugoslavia, Switzerland and Hungary also took part. This conference was an important signal for the further international dissemination of orienteering. On May 21, 1961, the International Orienteering Federation (IOF) was founded in Copenhagen , to which at that time associations from Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the FRG, the GDR, Switzerland and Hungary belonged. In 1962, the IOF hosted the first European championships in Løten, Norway , followed by the first world championships in Fiskars, Finland in 1966 . The beginning of the international standardization of orienteering maps in 1966 also coincides with this time. The history of the large multi-day orienteering events also began in the 1960s. The first O-rings were held in 1965 , a competition that has taken place annually in Sweden since then and which grew to a size of 25,000 participants in the following decades. By 1969 the IOF already had 16 member countries, with Japan and Canada for the first time non-European nations were also represented.

In 1977 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided to recognize orienteering. In the following year, the IOF established the official post description signatures.

An unofficial World Cup was held for the first time in 1983, the first official IOF Orienteering World Cup followed in 1986. In 1994, an electronic post control system was used for the first time in a World Cup race, and in the following years electronic control also established itself in popular sport. A year later, with the start of the Park World Tour, attempts were made to bring orienteering closer to the cities and thus to open up new audiences. Other important competition series introduced during the 1990s were the Junior World Championships (JWOC), established in 1990, and the Senior World Championships (WMOC), which were first held in the Czech Republic in 1998.

Currently (January 2016) the IOF has 79 member nations. While there are hardly any states left in Europe, America and East Asia, there are so far only a few member nations in Africa and the Arab world.

literature

- Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- Wilfred Holloway, Jörg Mumme: Orienteering: Endurance sports for leisure and health . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1987.

- Erich Krauss: Orienteering . Sports publishing house Berlin 1980.

- Stefan Cornaz , Herbert Hartmann: Orienteering (orienteering) as a leisure sport in schools and clubs. A didactic and methodical introduction. Verlag Karl Hofmann, Schorndorf 1978.

- Stefan Cornaz , Roland Hirter: orienteering. Smart jogging. Hallwag Verlag, Bern 1981.

- Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 .

- International Orientierungslaufverband (Ed.): Scientific Journal of Orienteering . ISSN 1012-0602 ( Online [accessed February 18, 2020]).

Web links

Orienteering associations

- International Orienteering Federation (IOF)

- German orienteering portal

- Austrian Association for Orienteering (ÖFOL)

- Swiss orienteering association

- Swedish orienteering association

useful information

- World of O - News, runners and card archive, WoO-TV

- Swiss orienteering lexicon

- Information on orienteering from the point of view of nature conservation authorities ( memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) at the Internet Archive

- Orienteering Wiki

Individual evidence

- ↑ International Orienteering Federation (Ed.): Competition Rules for International Orienteering Federation (IOF) Foot Orienteering Events 2010 . 2011, p. 19 (English, IOF Foot Orienteering Competition Rules 2011 [PDF; 335 kB ; accessed October 24, 2011]).

- ↑ a b c Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 21 .

- ^ A b International Orienteering Federation (Ed.): Competition Rules for International Orienteering Federation (IOF) Foot Orienteering Events 2010 . 2010, p. 15–16 (English, IOF Foot Orienteering Competition Rules 2010 [PDF; 331 kB ; accessed on November 7, 2010]).

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 64 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ↑ Björn Persson, Andreas Dresen, Søren Nielsen, Christopher Shaw, László Zentai: International Specification for Orienteering Maps . Ed .: International Orienteering Federation . 2000, p. 4 (English, International Specification for Orienteering Maps 2000 [PDF; accessed on November 7, 2010]). International Specification for Orienteering Maps 2000 ( Memento of the original dated November 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ International Orienteering Federation map commission (ed.): International Specification for Sprint Orienteering Maps (ISSOM) . 2006, p. 6 (English, online [PDF; accessed December 24, 2010]). online ( Memento of the original from December 18, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Björn Persson, Andreas Dresen, Søren Nielsen, Christopher Shaw, László Zentai: International Specification for Orienteering Maps . Ed .: International Orienteering Federation . 2000, p. 24 (English).

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 47 .

- ↑ Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 31 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 29 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 174 .

- ↑ a b Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 51-52 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 107-109 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 115 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 101 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 106-107 .

- ↑ Navigation Marathon and Dundurn Rogaine on sleepmonsters.de, accessed on November 16, 2010.

- ↑ a b Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 142-144 .

- ^ A b Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 65–67 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 73 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ^ Canoe and Kayak Orienteering of the Western Hemisphere. Western Hemisphere Affiliation of Canoe and Kayak Orienteers, archived from the original on October 27, 2009 ; Retrieved November 14, 2010 .

- ↑ German Tramp sports community. DTSG, accessed January 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 25 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 16 .

- ↑ Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 29 .

- ↑ a b Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 38-39 .

- ↑ a b c Uwe Dresel, Heinz Helge Fach, Roland Seiler: Orienteering training . More than 40 practical training examples. Competition preparation. Coaching. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89899-381-4 , pp. 23–24 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 40 .

- ↑ a b Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 16 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 150 .

- ↑ Björn Persson, Andreas Dresen, Søren Nielsen, Christopher Shaw, László Zentai: International Specification for Orienteering Maps . Ed .: International Orienteering Federation . 2000, p. 14 (English, International Specification for Orienteering Maps 2000 [PDF; accessed November 7, 2010]). International Specification for Orienteering Maps 2000 ( Memento of the original dated November 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 15-16 .

- ^ A b Uwe Dresel, Heinz Helge Fach, Roland Seiler: Orienteering training . More than 40 practical training examples. Competition preparation. Coaching. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89899-381-4 , pp. 36–37 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 34 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ^ Uwe Dresel, Heinz Helge Fach, Roland Seiler: Orienteering training . More than 40 practical training examples. Competition preparation. Coaching. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89899-381-4 , pp. 42 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 41 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ^ Uwe Dresel, Heinz Helge Fach, Roland Seiler: Orienteering training . More than 40 practical training examples. Competition preparation. Coaching. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89899-381-4 , pp. 30 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Roland Seiler: Of ways and detours . Information processing and decision-making in orienteering. In: Subject: Psychology and Sport . bps, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-922386-38-5 , p. 46 .

- ^ Uwe Dresel, Heinz Helge Fach, Roland Seiler: Orienteering training . More than 40 practical training examples. Competition preparation. Coaching. Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89899-381-4 , pp. 48–49 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 33 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ↑ a b c Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 194-198 .

- ^ Kurt Biener: Sports medicine . Canoe - rowing - judo - orienteering - ice hockey - water polo. tape 3 . Habegger, Derendingen-Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85723-219-6 , pp. 138 .

- ^ Kurt Biener: Sports medicine . Canoe - rowing - judo - orienteering - ice hockey - water polo. tape 3 . Habegger, Derendingen-Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85723-219-6 , pp. 136 .

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 12 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ↑ Dante Bettucchi: Lo Sport dell'orientamento . gare e passegiate con carta e bussola. Mondadori, Milano 1979, p. 116-117 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 213-214 .

- ↑ Environment Commission ( Memento of the original of December 18, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed January 22, 2011.

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 19 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ↑ Park World Tour , accessed November 15, 2010.

- ^ Ian Bratt: Orienteering . Training - technique - competition. 1st edition. Pietsch, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-50447-2 , p. 77 (English: Orienteering. The essential guide to equipment and techniques . Translated by Hermann Leifeld).

- ↑ a b c Tom Renfrew: Orienteering . In: Outdoor pursuits series . Human Kinetics, Champaign 1997, ISBN 978-0-87322-885-5 , pp. 3–4 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Ernst Biedermann, Jules Fritschi: The orientation sport . An introduction. Paul Haupt, Bern 1952, p. 5 .

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 21 .

- ^ Kurt Biener: Sports medicine . Canoe - rowing - judo - orienteering - ice hockey - water polo. tape 3 . Habegger, Derendingen-Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85723-219-6 , pp. 130 .

- ↑ O-rings ( Memento of the original from August 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at www.oringen.se, accessed on November 6, 2010.

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 17 .

- ↑ a b c d Heiner Brinkmann: Orientierungssport . Leisure time and competition. Limpert, Frankfurt 1967, p. 1-2 .

- ^ A b Kurt Biener: Sports medicine . Canoe - rowing - judo - orienteering - ice hockey - water polo. tape 3 . Habegger, Derendingen-Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85723-219-6 , pp. 126 .

- ↑ a b c d e The historic controls of the world. (No longer available online.) Center for Orienteering History, archived from the original on September 21, 2010 ; accessed on November 14, 2010 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c Steven Boga: Orienteering . The Sport of Navigating with Map & Compass. Stackpole, Mechanicsburg 1997, ISBN 978-0-8117-2870-6 , pp. 1–2 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Heiner Brinkmann: Orientierungssport . Leisure time and competition. Limpert, Frankfurt 1967, p. 4-5 .

- ^ Kurt Biener: Sports medicine . Canoe - rowing - judo - orienteering - ice hockey - water polo. tape 3 . Habegger, Derendingen-Solothurn 1985, ISBN 3-85723-219-6 , pp. 129 .

- ↑ Heiner Brinkmann: Orientierungssport . Leisure time and competition. Limpert, Frankfurt 1967, p. 7-8 .

- ^ Past & present. (No longer available online.) IOF, archived from the original on November 18, 2010 ; Retrieved November 14, 2010 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Heiner Brinkmann: Orientierungssport . Leisure time and competition. Limpert, Frankfurt 1967, p. 9 .

- ↑ Swiss Society for Cartography (ed.): History of the orienteering map . Autumn conference 2003. 2003, p. 3 ( kartographie.ch [PDF; accessed on January 1, 2011]). History of the orienteering map ( Memento of the original from May 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Günter Kreft: Orienteering . Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-87439-178-7 , p. 17 .

- ^ World Cup 1986. IOF, archived from the original on June 20, 2010 ; accessed on November 14, 2010 (English).

- ^ IOF: National Federations. Retrieved September 20, 2012 .