Quechua (people)

Quechua or Ketschua , in Bolivia Qhichwa , in Peru also Qichwa , in Ecuador Kichwa is a collective name for members of the ethnic groups whose native language is the Quechua (or one of the Quechua languages) is. The name of the people who speak Quechua is Runakuna ("people"; in Junín and parts of Ancash: Nunakuna ; singular: Runa or Nuna ).

Ethnonym

The word Quechua or Qhichwa ( southern Quechua ), Qichwa ( Chanka-Quechua , Ancash-Quechua ), Qiĉwa ( Wanka-Quechua , Cajamarca-Quechua , Inkawasi-Kañaris ), Kichwa ( Quichua , northern Quechua) or Qheswa (spelling of the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua ) means in the Quechua languages "valley" or the altitude "Quechua" , which is why its inhabitants traditionally Qhichwa runa or Kichwa runa , "people of the high zone Quechua" (in contrast to the people of the Yunka or the Puna ), from which the language name Qhichwa simi or Kichwa shimi , "language of the high zone Quechua", is derived. In modern Quechua texts, however, Qhichwa runa or simply Qhichwa (plural Qhichwakuna ) stands for “speaker of the Quechua language” (Qhichwa simi parlaq, Qhichwa simi rimaq) . The same applies to the corresponding Spanish expression (los) quechuas .

Historical and socio-political background

The speakers of the Quechua language, a total of around 9-14 million in Peru , Bolivia , Ecuador , Colombia , Chile and Argentina , have so far developed little or no common identity. The different Quechua variants differ so much that mutual understanding is not possible. It should be noted that Quechua was not only spoken by the Incas , but e.g. T. also by long-time enemies of the Inca Empire , B. the Huanca ( Wanka-Quechua is a Quechua variant still spoken in the Huancayo area ), the Chanka (Chanca - dialect of Ayacucho) or the Kañari (Cañar) in Ecuador. The Quechua was so spoken of some of these nations the Wanka before the Incas in Cusco, while other peoples, especially in Bolivia but also in Ecuador, the Quechua language took over until the Inca period or after. The Spanish colonial administration and the church promoted the spread of Quechua as a lingua franca .

In Peru , Quechua was declared the second official language in 1969 under the military government of Juan Velasco Alvarados . Recently there have been tendencies towards nation-building among Quechua-speakers, especially in Ecuador ( Kichwa ), but also in Bolivia, where the linguistic differences are only minor compared to Peru. Expression of this is z. B. the umbrella organization of the Kichwa peoples in Ecuador, ECUARUNARI (Ecuador Runakunapak Rikcharimuy) . But also some Christian organizations (e.g. the evangelical radio HCJB , la “Voz de los Andes”) speak of a “Quichua people”. In Bolivia, on the other hand, the term “Quechua nation” appears e.g. B. on behalf of the "Education Council of the Quechua Nation" ( Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua , CENAQ), which is responsible for Quechua teaching and intercultural bilingual education in the Quechua- speaking areas of Bolivia. As part of Bolivia's policy as a plurinational state, students are encouraged to identify as Quechua in Quechua-language or bilingual classes. In Peru, on the other hand, there are no comparable national or supraregional Quechua organizations, so this is not reflected in a coordinated language policy for Quechua. A local or regional indigenous identity is still important, for example to the ethnic group or "nation" Qanchi in the province of Canchis (Cusco region). In recent times, but also the identification of indigenous politicians or other public figures playing as Quechuas an increasing role, such as when coming from Ayacucho politician Tania Pariona Tarqui consider when client acceptance as a Member of the Peruvian Congress in 2016 their oath, Ayacucho Quechua for abandoned the pursuit of the “good life” ( allin kawsayninta maskaspa) of the Quechua and other indigenous peoples, as did Oracio Pacori Mamani from Puno, who swore “for the Quechuas and Aymaras” of his region. A 2006 study on the Regional Academy of the Quechua Language in Cajamarca (ARIQC), which is supported by indigenous people from the Cajamarca region , came to the conclusion that the reappropriation of the discriminated and repressed indigenous language meant the rejection of an imposed, degrading identity while at the same time developing a new, positive indigenous Quechua identity. In the city of Huamanga / Ayacucho, an organization founded by women in times of armed conflict , Chirapaq (“rainbow” or “rain of falling stars”), and the associated youth organization Ñuqanchik (“ we ”) are developing a positive Quechua -Identity related. This organization (in which Tania Pariona was also active) started a campaign for an open commitment to an indigenous identity in connection with the 2017 Census under its chairman, Quechua activist Tarcila Rivera Zea .

Material culture and social history

Despite the ethnic diversity and linguistic and dialect differences, the Quechua ethnic groups have a number of common cultural characteristics that they essentially share with the Aymara or all indigenous peoples of the Central Andes.

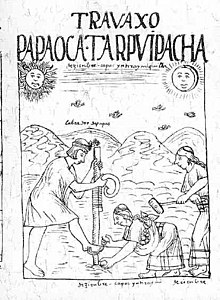

Traditionally the - locally oriented - Quechua identity is inextricably linked with the traditional economy. Their basis is agriculture in the lower regions, and grazing in the higher regions of the Puna . The typical Andean community comprises several altitudes and thus also the cultivation of a variety of crops and livestock. The land traditionally belongs to the village community ( ayllu ) and is cultivated jointly or distributed every year for cultivation. Before the arrival of the Europeans, the fields were dug up using only human muscle power using a step grave (chakitaklla) . In areas that are difficult to access, such as Q'ero (Cusco region, Peru), this technique has survived to this day, even if working with a plow and team of oxen is more common.

During the colonial era , the encomienda system was introduced, under which the Spanish crown gave land to aristocrats for use - but not as property - with the indigenous peoples who lived there being obliged to do labor for the encomenderos . The harsh conditions of exploitation repeatedly led to uprisings by the indigenous peasants, who were violently suppressed. The largest of these uprisings took place 1780–1781 under the leadership of José Gabriel Kunturkanki .

The founding of the independent republics in South America by the Criollos at the beginning of the 19th century favored the appropriation of formerly indigenous lands by large landowners , because corresponding laws from the colonial times, which had prevented this to the annoyance of the Criollos , were removed. Simón Bolívar decreed in 1825 for Peru and Bolivia that the communal lands were to be divided among the indigenous people and forbade their resale - limited until 1850. As early as 1847, however, President José Ballivián declared these lands to be state property, which quickly passed into the hands of private interested parties. When Bolivia became independent, three quarters of the arable land was still in indigenous hands, in 1847 this was only half, with 3,100 comunidades and 5,100 haciendas . The large landowners appropriated the land of the indigenous people or a large part of it and forced the indigenous people into debt bondage (in Ecuador referred to as Huasipungo , from Kichwa wasipunku , “front door”).

Land occupations and expulsions of the hacendados by indigenous farmers, who were organized in Peru in the Confederación Campesina del Perú , accompanied the takeover of reform-minded juntas in the middle of the 20th century, for example in 1952 in Bolivia ( Víctor Paz Estenssoro ) and 1968 in Peru ( Juan Velasco Alvarado ) . With the land reforms they initiated , the large landowners were expropriated and, especially in Bolivia, the land was distributed to the Indian farmers as individual property. This meant a break with the traditional Quechua and Aymara cultures. On the other hand, Ayllus have remained in remote areas to this day (see for example the Peruvian Quechua community Q'ero ).

The struggle for land rights is still a focal point of everyday political life in the Quechua. More recently, the Kichwa ethnic groups of Ecuador , organized in the ECUARUNARI association, have been able to fight for communal land titles and the restitution of land - also through militant actions. Among the Kichwa of the lowlands, the case of the community of Sarayaku became particularly well known, which successfully fought against the expropriation and exploitation of the rainforest for oil production over many years .

A distinction is made between two main types of joint work: Minka is joint work for projects in the common interest (e.g. building communal objects). Ayni , on the other hand, is working in mutual help, whereby members of the Ayllu help a family with larger projects of their own (e.g. house building) and everyone can benefit from this help on the one hand, and help others at some point on the other.

Important elements of the material culture of almost all Quechua ethnic groups are also a number of traditional crafts :

This includes the weaving of cotton and wool (from llamas , alpacas , guanacos , vicuñas ) that was traditionally passed from the Inca period or before . The wool is dyed with natural dyes. Numerous weaving patterns ( pallay ) are known.

When building houses, mud bricks ( tika or Spanish adobe ) dried in the warm air are usually used or twigs and mud mortar are used. The roofs are covered with straw, reeds or Punagras (ichu) .

The dissolution of traditional economic methods, regional z. B. through mining and subsequent proletarianization , has usually led to a loss of ethnic identity as well as the Quechua language. This also applies to permanent emigration to the big cities (especially Lima ), which results in acculturation to the local Hispanic society.

Recent examples of persecution of Quechua

To the present day, Quechua has been the victim of political conflict and ethnic persecution. In the civil war in Peru in the 1980s between the state power and Sendero Luminoso , around three quarters of the 70,000 fatalities were Quechua, while those responsible in the warring parties were without exception whites and mestizos. Dealing with these traumatic experiences led to a style of its own for the Quechua song, the “remembrance song”, based on the Ofrenda (1981) by Carlos Falconí Aramburú (* 1937), interpreted by Manuelcha Prado , among others . With his Quechua novel Aqupampa , published in 2016, Pablo Landeo Muñoz also grapples with the consequences of the war by describing the living conditions of the Quechua- speaking rural population who moved to the city because of the war.

The policy of forced sterilization under Alberto Fujimori affected almost exclusively Quechua and Aymara women, a total of over 200,000. The Bolivian film director Jorge Sanjines already deals with the problem of forced sterilization in his Quechua-language feature film Yawar Mallku from 1969.

Ethnic discrimination still plays a role at parliamentary level today: When the newly elected Peruvian MPs Hilaria Supa Huamán and María Sumire took their oath in Quechua on July 25, 2006 - for the first time in the history of Peru in an indigenous language - the Peruvian refused Parliamentary President Martha Hildebrandt and the Presidium Member Carlos Torres Caro stubbornly accept this.

religion

Virtually all Andean Quechua have been nominally Catholic since colonial times ; however, since the 20th century, Protestant churches expanded. In many areas forms of traditional religion live on, mixed with Christian elements ( syncretism ). The Quechua ethnic groups also share the traditional religion with the other Andean peoples. The belief in mother earth ( Pachamama ) , which gives fertility and which is therefore regularly offered to smoke or drink offerings, survives in the Andes . Also important are the mountain spirits ( apu ) and smaller local deities ( wak'a ) , which are still worshiped, especially in southern Peru.

The recurring historical experience of genocide was processed by the Quechua in the form of various myths . This includes B. the figure of Nak'aq or Pishtaku ("butcher"), the white murderer who sucks the fat from the murdered indigenous people, or the song of the bloody river. In the myth of Wiraquchapampa , the Q'ero tell of a victory by the Apus over the Spaniards . Among the myths that are still alive today, the Inkarrí myth, which is widespread in southern Peru, is particularly interesting, as it forms a connecting cultural element of Quechua in the regions from Ayacucho to Cusco .

Probably of European origin, the myth of Juan Oso , the son of a bear and a woman he abducted, as well as the dance of bears that is widespread in the Andes (bear and also bear dancer: ukumari , in Cusco ukuku ). In the Cusco region, the bear myth is linked to the legend of the Condenado (damned), which is widespread in the Andean region and can be traced back to Catholic influence , a soul condemned for serious sins, which terrorizes people and can only find salvation if someone pays the debt and such kills the damned for good. Through his victory over the Condenado , the son of a bear finds recognition and can integrate, whereby the Condenado is also redeemed through his final death.

The myth of the child-eating witch Achikay , which is particularly widespread in central Peru ( Ancash , Huánuco ) and is associated with the heartlessness of people in times of famine, is traced back to a pre-colonial core .

Additional articles on Quechua-speaking ethnic groups

The Quechua ethnic groups listed here are only a selection. The delimitation is also different. In some cases, village communities with a few hundred people are given here, in some cases also ethnic groups with more than a million people.

- Inca (historical)

Ecuador

Peru

Lowlands

Highlands

Bolivia

photos

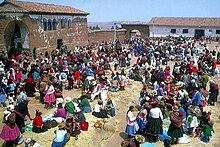

Woman in the indigenous market in Saquisilí near Latacunga , Ecuador

Inti Raymi solstice festival in Chibuelo , Ecuador

Wititi dancers in Chivay in the Colca Valley , Peru

Women in traditional costume in Cotacachi , Ecuador ( Otavalos )

See also

- ECUARUNARI

- the Quechua language (dialects including Kichwa and Southern Quechua )

- Inkarrí

- Bolivian dances

swell

- ↑ Jesús Lara: Folk poetry of the Quechua. Collected in the valleys of Cochabamba. Quechua and German. German by Ludwig Flachskampf and Hermann Trimborn. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1959.

- ^ A b Libro de Ciencias Sociales y Naturales. Material de apoyo para la educación del Pueblo Quechua. Nivel de educación: Primaria comunitaria vocacional. Campo: Comunidad y Sociedad. Vida, tierra y territorio. 2 ° año de escolaridad . Qhichwakuna kanchik. Somos Quechuas. P. 12.

- ↑ Qhichwa simip nanchariynin ( Memento of the original from July 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Ministerio de Educación, Chuqi Yapu (La Paz) 2011.

- ↑ Quechua . Series Introducción histórica y relatos de los pueblos originarios de Chile. Fucoa, Santiago de Chile 2014. p. 108: Chiqa pachap kasqan.

- ^ Nonato Rufino Chuquimamani Valer, Carmen Gladis Alosilla Morales: Reflexionando sobre nuestra lengua - Ayakuchu Chanka Qichwa simi . Ministerio de Educación, Lima 2005.

- ↑ ECUARUNARI - Confederación Kichwa del Ecuador , Confederación de los Pueblos de la Nacionalidad Kichwa.

- ↑ CUNAN CRISTO JESUS BENDICIAN HCJB: "El Pueblo Quichua" ( Memento from July 18, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (former Quichua-language site of Radio HCJB ).

- ↑ Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua: Quienes somos , Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua / Qhichwa Suyu Yachachiymanta Umalliq: Currículo Regionalizado de la Nación Quechua . Sucre 2012.

- ↑ Melquíades Quintasi Mamani: Más allin mejor kanankuta munanku. Visión educativa de la "Nación" Qanchi . Plural, PINSEIB, PROEIB Andes, La Paz 2006. 248 pages. Summary (Spanish)

- ^ Congresista Tania Pariona juramentó en quechua y por los pueblos indígenas . Diario Correo, July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Congreso: cinco parlamentarios juraron en lenguas originarias . El Comercio, July 22nd, 2016.

- ↑ Yina Miliza Rivera Brios: Quechua language education in Cajamarca (Peru): History, strategies and identity. University of Toronto, 2006. ISBN 0-494-16396-8 , 9780494163962

- ↑ Tapio Keihäs: ¿Ser y hablar quechua? The realidad sociolingüística de Ayacucho desde la visión subjetiva de los jóvenes indígenas. Ideologías e identidades en el discurso metalingüístico. Master thesis, University of Helsinki 2014.

- ↑ Jóvenes predicen un futuro incierto para las lenguas indígenas. ( Memento of the original from March 21, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Chirapaq Ayacucho, accessed March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Censo 2017: Tarcila Rivera disertará sobre identidad indígena. Chirapaq Ayacucho, accessed March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Inge Sichra. La vitalidad del quechua, chap. 2.3: Bolivia independiente - conservación del feudalismo agrario y consolidación de estructuras, pp. 86–89. Cochabamba 2003.

- ↑ Orin Starn: Villagers at Arms: War and Counterrevolution in the Central-South Andes. In Steve Stern (Ed.): Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980-1995 . Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1998, ISBN 0-8223-2217-X .

- ↑ Jonathan Ritter: Complementary Discourses of Truth and Memory. The Peruvian Truth Commission and the Canción Social Ayacuchana . Part III (Musical Memoralizations of Violent Pasts), 8 in: Susan Fast, Kip Pegley: Music, Politics, and Violence . Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connecticut 2012.

- ↑ Mass sterilization scandal shocks Peru, July 24, 2002, BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/2148793.stm

- ↑ Perú: Congresista quechua Maria Sumire sufrió presiones para juramentar en español. http://www.servindi.org/archivo/2006/927

- ↑ Congresistas indígenas sesionarán en Quechua. Diario Hispano Peruano, August 10, 2006. http://www.ociocritico.com/peru/noticias/060810quechua.php

- ↑ Examples ( Ancash-Quechua with Spanish translation) on S. Hernán AGUILAR: Kichwa kwintukuna patsaatsinan ( Memento from July 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). AMERINDIA n ° 25, 2000. Pishtaku 1, Pishtaku 2 (in Ankash-Quechua , with Spanish translation) and on http://www.runasimi.de/nakaq.htm (only Chanka-Quechua )

- ↑ Carnival Tambobamba. In: José María Arguedas: El sueño del pongo, cuento quechua y Canciones quechuas tradicionales. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago de Chile 1969. Online: http://www.runasimi.de/takikuna.htm#tambubamba (in Chanka-Quechua ). German translation in: Juliane Bambula Diaz and Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 172.

- ↑ a b Thomas Müller and Helga Müller-Herbon: The children of the middle. The Q'ero Indians. Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-88977-049-5 .

- ↑ http://www.runasimi.de/inkarri.htm (in Quechua)

- ↑ Juliane Bambula Diaz and Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 231 ff.

- ↑ Gerald Taylor: Juan Puma, el Hijo del Oso. Cuento Quechua de La Jalca, Chachapoyas ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . En: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines, N ° special: "Tradición oral y mitología andinas", Lima, 1997, Tomo 26, Nº3.

- ↑ Robert Randall (1982): Qoyllur Rit'i, an Inca fiesta of the Pleiades: reflections on time & space in the Andean world ( memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Etudes Andines XI, Nº 1-2, pp. 37-81. On the Bear's Son and Condenado : 43–44, 55–59.

- ↑ Francisco Carranza Romero: Achicay: Un relato andino vigente . In: David J. Weber, Elke Meier (ed.): Achkay - Mito vigente en el mundo quechua ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Lingüística Peruana series 54. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano ( SIL International ), Lima 2008, pp. 13-19.

literature

- Ann Marie B. Bahr, Martin E. Marty: Indigenous religions . Infobase Publishing, New York 2005. The Quechuas , pp. 124-141. ISBN 978-0-7910-8095-5 .

- Marisol de la Cadena: Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds . Duke University Press, Durham and London 2015, ISBN 978-0-8223-5944-9 . (Field study, based on conversations with Mariano & Nazario Turpo, Quechuas from the Cusco / Peru region)

- Álvaro Ezcurra Rivero: Dioses, bailes y cantos. Indigenismos rituales Andinos en su historia . Narr, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8233-6736-9 .

- Utta von Gleich (Ed.): Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Conflict Factor or Development Potential? Vervuert, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-89354-245-0 .

- Eva Gugenberger: Identity and language conflict in a pluriethnic society. A Sociolinguistic Study of Quechua Speakers in Peru . Wiener Universitätsverlag (WUV), Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-85114-225-X .

- Manuel M. Marzal: The Quechua religion in the southern Andean Peru . In: Thomas Schreijäck (ed.): The Indian faces of God . Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation (IKO), Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-88939-051-X , pp. 82–144.

- Thomas Müller, Helga Müller-Herbon: The children in the middle. The Q'ero Indians . Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-88977-049-5 .

- Roger Neil Rasnake: Domination and Cultural Resistance: Authority and Power among an Andean People . Duke University Press, Durham and London 1988, ISBN 0-8223-0809-6 . (Study on the Quechua-speaking Yura in the Department of Potosí / Bolivia)

- Matthias Thonhauser: In the face of the earth. On the importance of Indian religiosity in liberation processes using the example of a community in Surandino Peru . Brandes and Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-86099-302-X . (Study especially on the Comunidad Campesina Quico in Paucartambo / Peru)

- Rocha Torrico, José Antonio: “Looking ahead and back”. Ethnic ideology, power and the political with the Quechua in the valleys and mountain regions of Cochabambas . Dissertation, Ulm 1997.

- Sondra Wentzel: Bolivia - Problems and perspectives of the high and lowland Indians . In: Society for Threatened Peoples (ed.): "Our future is your future". Indians today. An inventory of the Society for Threatened Peoples . Luchterhand-Literaturverlag, Hamburg and Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-630-71044-1 , pp. 235–242.

- Jonas Wolff: Democratization as a risk to democracy? The political crisis in Bolivia and Ecuador and the role of the indigenous movement (= PRIF Report 6/2004). Hessian Foundation for Peace and Conflict Research, Frankfurt am Main 2004.

Web links

- Literature on Quechua in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin

- ECUARUNARI - Official Website (Spanish)

- Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua (CENAQ), Bolivia (Spanish)

- Inkawasi Awana - El tejido de la casa del Inka ( Memento of October 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (The fabric of the house of the Inca, Spanish)

- La Voz de los Andes - Pueblo Quichua - ¿Quienes Somos? ( Memento of March 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (Christian radio, evangelical, Spanish)

- Nina Schierstaedt: Indigenous people in Ecuador. Between institutional influence and street fighting . KAS -AI 5/06, pp. 72-105 (PDF file; 152 kB).