Rugjer Josip Bošković

Rugjer Josip Bošković (born May 18, 1711 in Ragusa (now Dubrovnik ) , Republic of Ragusa ; † February 12, 1787 in Milan , Duchy of Milan ) was a Croatian mathematician , physicist and Catholic priest who was also involved in astronomy , natural philosophy and poetry as well worked as a technician and geodesist , from the Republic of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik in Croatia ).

Diversity of names and activities

In the specialist literature Bošković is present under the following spellings:

- Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich

- Ruđer (Roger) Bošković

- Ruđer Josip Bošković

- Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich

- Roger Joseph Boscovich , and Roger Boscovich

- Josip Ruđer Bošković

- Rugjer (Rudjer) Josip Bošković (or written without diacritics).

Bošković stands out among his contemporaries for the diversity of his activities. He is one of the last polymaths in southern Europe . He spent most of his life in Italy. As a scientist and consultant he was also active in the Papal States , in Austria and France , as well as in the diplomatic service and as a poet .

His name is still linked to important advances in geodesy , adjustment calculations and natural philosophy , as well as to the beginnings of atomic physics . He has also made a name for himself as an appraiser for endangered monumental buildings. The six decades of his academic activity are spread over ten European countries and around 15 university cities. Individual historians of science consider Bošković to be a kind of founder of atomic theory, a forerunner, even the founder of atomic physics .

From Ragusa to Rome

His parents were Nikola Bošković, a farmer from the village of Orahov Do in Herzegovina, and Paola Bettera, a Romanian from Dubrovnik.

As a boy, Rugjer attended the prestigious Jesuit grammar school in his hometown Ragusa, where he soon attracted attention due to his talent for science and languages. At the age of 14 he was sent to Rome to continue his studies , where he later entered the Jesuit order . At the Collegium Romanum he received a solid education in natural sciences , philosophy and theology.

Bošković published his first works on astronomy and geodesy as early as 1723 at high school. For the next three decades he lived mainly in Rome, where he was ordained a priest in 1744. In the same year he was appointed professor for mathematics and philosophy at the Collegium Romanum .

Scientist and diplomat in Europe

Bošković counted with Joseph Liesganig , Christoph le Maire and others to those scientifically active Jesuits who dealt intensively with new currents in physics and the study of the earth's body. He was fascinated by Newton's theory of gravity and defended it against numerous attacks.

Between 1750 and 1753, on behalf of the Pope , he directed the degree measurement from Rome to Rimini , where an approximately 200 km long meridian arc was laid out to determine the regional earth radius and measured astrogeodetically . Bošković's contacts with the land surveying of the then great powers Austria and France prompted him to search for methods of compensation calculation in order to optimally derive the parameters of the earth's figure from several - slightly contradicting - degree measurements .

In 1756 he made his first diplomatic trip to Lucca in central Italy and to Vienna . He left Rome three years later and went to Paris , and a year later to London, Flanders and Germany . Other trips took him to Poland and Warsaw , as well as to the Ottoman capital Constantinople .

Contact to numerous researchers and philosophers

Due to his universal way of thinking, sociability and interdisciplinary interests, Bošković had contact with numerous well-known researchers and intellectuals. Particularly noteworthy among them are:

- several regents and popes, numerous ministers and diplomats,

- Scientists like Bradley, Clairaut, Franklin, Lalande, Laplace, Mairan, Michell and various philosophers

- the geoscientists Bouguer, Liesganig, Lemaine, Maire, Maupertuis u. a.

- the astronomer Karl Scherffer, who worked in Graz and later (from 1753) in Vienna,

- but also longer professional oppositions, e.g. B. with d'Alembert .

Astronomy and optics in Italy and France

In 1763 he took up a professorship at the University of Pavia , but soon moved to Paris and later taught in Milan . At the nearby college of Brera he set up an observatory and had some of it equipped at his own expense. His special research topics naturally included optics, solar physics and the determination of the sun's rotation by observing sunspots .

In the following years Bošković's diplomatic skills were in demand again when the abolition of the Jesuit order became apparent. After this turmoil he was appointed "Director of Optics " in the French Navy in 1773 . The king provided him with a salary of 8,000 livres . Soon, however - in the course of the Jesuit persecution - he was attacked by d'Alembert and other French scholars, so that he resigned his office and turned to Bassano , where he got the edition of his works.

Finally, at the age of 72, he returned to Milan, where he died of mental confusion five years later.

The lunar crater Boscovich and the asteroid (14361) Boscovich are named after him.

From Bošković's research in physics and astronomy

In Northern Italy, Bošković is counted among the most important scientists of the 18th century and in Croatia, along with Nikola Tesla, is considered the most outstanding physicist in the country. Numerous researchers in south-east Europe referred to his pioneering work, among which his dynamic atomistics stands out.

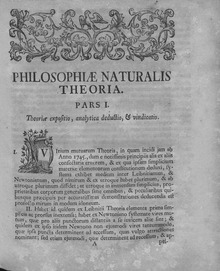

It is a precisely formulated system that is based on Newtonian mechanics . This work inspired Michael Faraday to his electric field theory. In an essay on natural philosophy and criticism of religion it says: According to J. BOSCOVICH, the "primae materiae elementa" of his atomic theory are "puncta penitus inextensa et indivisibilia, a se invicem aliquo intervallo disiuncta" (Theor. Philos. 1763, p. 41).

In another context, too, Bošković was fascinated by the concept of mass points - he systematically introduced them into physics as part of mathematical models.

Contributions to astronomy, geodesy, technology and poetry

Bošković also made important contributions to astronomy. Among them was a method for calculating the orbit of a planet from three measured positions in the starry sky, and the first geometric method for calculating the equator of a rotating celestial body from three observations of its surface shape. He also determined the elements of rotation of the sun from observations of sunspots.

For a similar task in the above-mentioned degree measurement from 1750 to 1753, he developed a calculation method to compensate for the small contradictions that occurred by minimizing the absolute sum of the residuals (remaining residual errors). When Carl Friedrich Gauss notes found on Bošković 'work to " orbit determination of the heavenly bodies" and the vertical deflection that for later asteroids like Ceres and the Hannover'sche state survey were useful.

Bošković and the structural engineering

In several libraries of southern Europe there are reports Bošković 'on the statics of large buildings. The two most famous cases are St. Peter's Basilica (1742) and the Vienna Court Library (1763). Regarding the latter, Empress Maria Theresa asked the scholar who was present at the Viennese court as envoy from Lucca to support the architect Nikolaus Pacassi in rescuing the dome of the state hall, which was threatened with collapse.

Bošković owes his fame as a civil engineer to a theoretically and practically well-founded report on St. Peter's Basilica in Rome from 1742, which he prepared with the Franciscan Fathers and mathematics professors Thomas Le Seur and François Jacquier . It is considered the first known static calculation and was described (by Hans Straub) as the “birth of civil engineering”. There were clear cracks in this world's tallest dome ; Their causes should be explored and suggestions for remedying the damage should be developed. The “mathematical physicist” was especially asked about the theory of processes. In the introduction to their report, they wrote:

"We may be obliged to apologize to the many who not only prefer practice to theory, but consider the first one alone to be appropriate and necessary, the second perhaps even harmful."

Poems and Aurora Borealis

Bošković wrote mainly in Latin , but also in French and Italian. His Latin style is classic and sometimes seems a bit old-fashioned. He wrote his own poems, but also published those by friends and commented on them scientifically.

The first (1747) was a poem by his teacher Caroli Neceti about the aurora borealis - the northern lights . Bošković's idea of this effect on the ionosphere was similar to Mairan's, but its height was still completely unknown. He assigned 825 miles to an apparition from December 1737 - which, interestingly, is much higher than the Earth's atmosphere was ascribed to in the 19th century .

The second "scientific poem" (1755) came from Father Benediktus Stay and was about modern philosophy. The more modern Bošković's research topics were (e.g. on Newton's theory of gravitation ), the freer the style of his writings became.

Honors

From 1748 he was a member of the Académie des Sciences . In 1760 he was accepted as an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg .

Most important works

- De expeditione ad dimetiendos duos meridiani gradus , Rome 1755

- Journal d'un voyage de Constantinople en Pologne , Paris 1772

- Theoria philosophiae naturalis redacta ad unicam legem virium in natura existentium , Vienna 1758, 2nd edition Venice 1763.

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Boscovich, Roger Joseph . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 2nd part. Publishing house of the typographical-literary-artistic establishment (L. C. Zamarski, C. Dittmarsch & Comp.), Vienna 1857, pp. 82–85 ( digitized version ).

- Hans Ullmaier: Puncta, particulae et phaenomena. The Dalmatian scholar Roger Joseph Boscovich and his natural philosophy. Wehrhahn, Laatzen 2005, ISBN 3-86525-015-7 .

- Helmuth Grössing and Hans Ullmaier (eds.): "Ruđer Bošković (Boscovich) and his model of matter". Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-7001-6797-6

- Karl-Eugen Kurrer : The History of the Theory of Structures. Searching for Equilibrium , Berlin: Ernst & Sohn 2018, pp. 921f. and p. 924f. (Biography), ISBN 978-3-433-03229-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Rugjer Josip Bošković in the catalog of the German National Library

- Rudjer Bošković, scholar and diplomat

- Rudjer Bošković Institute in Zagreb (English)

- Biography (English)

- History of geophysics

- Entry to Boscovich; Roger Joseph (1711–1787) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Technical school Ruđer Bošković in Zagreb (Croatian)

- Author profile in the database zbMATH

Individual evidence

- ↑ (here the autographs: [1] )

- ↑ (Ranking according to Google: 37000, 1900, 1300, 1000, <100 links)

- ↑ Thomas E. Woods: Great moments instead of the dark middle ages. MM Verlag, Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-928272-72-1 , p. 144 ff.

- ↑ Franka Miriam Brückler: 300th birthday of Ruđer Josip Bošković (Roger Joseph Boscovich) . Mathematics in Europe. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ↑ Istvan Szabo History of Mechanical Principles , 1987. Hans Straub History of Civil Engineering 1992

- ↑ Report of the meeting of the Austrian Academy of Sciences ( Memento of the original from January 1, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ List of members since 1666: Letter B. Académie des sciences, accessed on September 24, 2019 (French).

- ^ Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences since 1724: Rugjer Josip Bošković. Russian Academy of Sciences, accessed September 24, 2019 (Russian).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bošković, Rugjer Josip |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Boscovich, Roger Joseph; Boscovich, Ruggero Giuseppe; Boscovich, Ruggiero Giuseppe; Bošković, Ruđer; Bošković, Roger; Boskovic, oar; Bošković, Ruđer Josip; Boscovich, Roger; Bošković, Josip Ruđer; Bošković, Rudjer Josip; Boskovic, Rudjer Josip; Boskovic, Rugjer Josip |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mathematician, physicist and Catholic priest |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 18, 1711 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ragusa , city republic of Ragusa |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 12, 1787 |

| Place of death | Milan , Duchy of Milan |