Joseph Suess Oppenheimer

Joseph Ben Issachar Süsskind Oppenheimer (short Joseph Süss Oppenheimer , also defamatory Jud Süss ; born probably February or March 1698 in Heidelberg , Electoral Palatinate ; died on February 4, 1738 in Stuttgart , Duchy of Württemberg ) was court factor of Duke Karl Alexander von Württemberg . After the Duke's death, Oppenheimer was executed as a victim of a judicial murder on anti-Jewish accusations and his body was executed Displayed in a cage for six years.

Joseph Süss Oppenheimer served as a historical model for Wilhelm Hauff's novella Jud Suss from 1827 and Lion Feuchtwanger's novel Jud Suss from 1925; the Nazis used the story in 1940 for propaganda purposes for the anti-Semitic film Jud Suss .

Life

Early years

Joseph Süss Oppenheimer grew up in a middle-class family in Heidelberg in a respected Jewish merchant family. From 1713 to 1717 he made trips to Amsterdam , Vienna and Prague . The professions that Jews were allowed to take up at the time were largely limited to commercial and financial activities. As a rule, they were not allowed to own land or join guilds . Oppenheimer began successfully to earn his living in the Palatinate as a private financer; Debt collection was also one of his first activities. With the granting of credits to indebted nobles, he rose socially; he always stepped in when banks refused to finance the money-seekers' lavish lifestyle.

As a finance broker and banker, he quickly achieved wealth and prestige. Among other things, he worked for the Palatinate and Cologne electors. During a marriage brokerage on behalf of Duke Eberhard Ludwig von Württemberg , he met his nephew Karl Alexander in Wildbad in 1732 , who suffered from a chronic lack of money. In the same year, he appointed Oppenheimer to his court and war factor .

Counselor to the Duke

When Karl Alexander became Duke of Württemberg after Eberhard Ludwig's death on October 31, 1733 , Oppenheimer had become so important to him that he gave him a wide range of decisions on economic and financial issues in the state. In 1736 Oppenheimer was appointed to the Duke's Secret Finance Council and political advisor and quickly rose to the top. Duke Karl Alexander had converted from the Protestant to the Catholic creed long before his accession to the throne . In his four-year reign (1733–1737), a Catholic prince, advised by a Jew without full civil rights, ruled over a Protestant population, which created considerable tension.

In order to reconcile the desolate finances of the country with the absolutist need for representation and money of Duke Karl Alexander, Oppenheimer introduced numerous innovations in the sense of a mercantilist economic system. He founded a tobacco, silk and porcelain manufacture and also the first bank in Württemberg, which he ran himself. He taxed civil servants' salaries and sold trading rights for salt, leather and wine to Jews for high fees. He also traded in precious stones and metals, leased the state mint , organized lotteries and other games of chance and mediated in legal disputes.

Duke Karl Alexander decided the measures and reforms proposed by Oppenheimer in absolute power without the consent of the Protestant Württemberg provinces , although they would have granted the right of tax approval under the Tübingen Treaty , which was also considered the Württemberg constitution. Against the background of these political and denominational tensions, Oppenheimer's successful state restructuring, his prosperity and his rigid monetary and tax policy aroused envy, hatred and anti-Jewish resentment among many state officials and citizens . Since Oppenheimer was aware of these tensions, he wanted to resign from the Duke's service, but was forbidden to do so. The ruler is said to have threatened that he will have him declared outlawed if he leaves.

Fall and execution

When Karl Alexander died unexpectedly of pulmonary edema on March 12, 1737 , a "conservative revolt" ( Hellmut G. Haasis ) began against his progressive financial and economic policy. Since the Duke was no longer protecting Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer was arrested the same day by the commander of the vigilante group , Major von Röder, and placed under house arrest.

Immediately after Oppenheimer's arrest, all of his staff were arrested, his apartment sealed and all of his property confiscated, and private and business documents were confiscated. Oppenheimer's home furnishings and all of his valuables, insofar as they were in Württemberg, were publicly auctioned or sold on August 18, 1737, six months before his conviction. On March 30th, he was taken in a carriage under the strict guard of a general of 2 officers and 60 dragoons, first to tightened solitary confinement at Hohenneuffen Castle , where a first provisional interrogation took place. On May 30th, he was transferred to Hohenasperg Fortress , where he continued his hunger strike. The charges were high treason , lese majesty , robbery of state coffers, official dealing , corruption , desecration of the Protestant religion and sexual contact with Christian women. Among other things, he was accused of having molested a fourteen-year-old. However, their virginity was confirmed by two midwives. Luciana Fischer, 20 years her junior, a Christian and the eldest daughter of a noble family, had a relationship with Oppenheimer. She was arrested along with him and heard in nine interrogations. When she gave birth to a son in prison in Ludwigsburg on September 14, 1737, she admitted the sexual relationship. The infant died around the turn of the year 1737/38 in the icy penitentiary. Birth and death were kept secret from the father. The women's stories accused of him were quickly swept under the carpet when it turned out that there were also women of honor under his circumstances . There was no evidence of other charges based on anti-Jewish stereotypes. The court attorney Andreas Michael Mögling took over the defense of Oppenheimer. He wrote a letter of defense that was demonstrably submitted to the special court. The closed court, however, did not take notice of them, because the death sentence passed on January 9, 1738 had already been determined. The defense was removed from the case files. It was previously known from a copy (in the Tübingen University Library ), but it was not until 2011 that the Württemberg State Archives succeeded in acquiring the original, which had been in private hands until then and was therefore unknown. When the verdict was pronounced, criminal offenses were not named and no reasons were given. The death sentence was signed by Duke Carl Rudolf , the guardian of Karl Alexander's underage son Carl Eugen, on January 25, 1738, he is said to have said: "It is a rare occurrence that a Jew pays the bill for Christians". On January 30, the emaciated Oppenheimer (he had refused to eat because it was not kosher) was transferred to the Herrenhaus am Marktplatz in Stuttgart, where those sentenced to death were kept until their execution.

Oppenheimer was exhibited in a red-painted cage and promises to pardon him if he converted to Christianity, which he refused. Before his death he spoke the Shema of Israel . Mardochai Schloß , the head of the Jewish community, was allowed to assist him, but a rabbi was withheld from him.

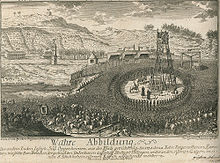

On February 4, 1738, the day of the execution , a massive military presence was shown: 1200 soldiers cordoned off the market square, 600 more secured the place of execution , citizen guards ran patrols and there were tightened controls at all city gates. At around 9 a.m., the 13-member court met in the mansion to announce the unanimous verdict. Oppenheimer, emaciated to a skeleton, threw himself on his knees and asked for mercy one last time , but in vain. He did not touch his executioner's meal . Then he was dragged into the cart. 120 grenadiers escorted the train to Galgenberg outside Stuttgart. Oppenheimer prayed incessantly. He had tied the Ten Commandments around his forehead with a black handkerchief. He also resisted the two clergymen who wanted to convert him to Christianity to the end. At the place of execution, grandstands were built, "especially stalls for cavalliers and dames" to protect against sun and rain. In the middle of the square the twelve-meter-high iron gallows towered on a high foundation: the tallest in the entire German Empire. Over 49 rungs had to be climbed. Above hung an iron cage painted red. More than 50 Stuttgart master locksmiths and journeymen had to make it so that they could not be declared dishonest according to the guild rules of the time . Four executioners pushed the condemned man up the ladder, where he was not hanged at the top but was strangled with a rope. A French executioner had been hired for the execution. The corpse was then lifted into the cage and the housing was locked several times. To intimidate and warn all Jews, the body was left in the cage, which was later forged into a balcony railing.

Since he had stated during the trial that he could not be hung higher than the gallows, the iron gallows built by the alchemist Georg Honauer in 1596 was used for his execution, in the sense that the higher the gallows, the more disgraceful the punishment. According to contemporary sources, a large number of people watched the killing on the execution site, the Stuttgart Galgenberg above the Tunzenhofer Steige, where the south entrance to the Prague cemetery is today . Numbers of up to 20,000 spectators are handed down at a festival-like event with booths and stands, beer and wine sales and the sale of leaflets with diatribes. Oppenheimer's body was put on public display in the iron cage for six years; it was not until 1744 that Duke Carl Eugen had it hanged and buried as his first government act when he took office.

The case files

Until 1918, the 7.5 meter shelf files were secret. Even in the 19th century, it was only possible to look into individual documents for research purposes. In the 19th century, the case files were transferred to the then Royal State Archives by the authorities involved. The files with the signature A 48/14 in the main state archive in Stuttgart have been freely accessible since 1918 . It comprises all documents from the years 1727 to 1772, starting with the oldest confiscated documents up to the dissolution of the inventory deputation responsible for Oppenheimer's assets in 1772.

Initial investigations showed meticulous documentation of every possible suspicion and all interrogation protocols. The aim of the prosecutors was to prove that Oppenheimer must have been the evil advisor to Duke Karl Alexander. All means were right, such as the demand for denunciation , which was read publicly and posted in town halls throughout Württemberg. 607 people responded to this request. Even the auction proceeds were listed except for pennies and pennies.

The case files essentially comprise:

- the interrogation protocols and investigations of the Inquisition Commission, which had prepared the subsequent trial,

- confiscated documents from Oppenheimer's private rooms,

- the so-called land reports that were received as a result of the public request to denounce Oppenheimer,

- regular reports from the inventory deputation entrusted with the property,

- the files from the court process with judgment.

The extremely extensive trial files have not been fully worked through up to the present. Deciphering and assigning the handwritten and often incoherently collected records is complicated. This means that the source basis for a complete assessment of the historical person Joseph Suss Oppenheimer has not yet been fully developed scientifically.

Separate from the specific files of the Defendant Oppenheimer there are further sub-files of co-defendants Oppenheimer:

- A 48/01 Johann Christoph Bühler

- A 48/06 Jakob Friedrich Hallwachs

- A 48/08 Professor Johann Friedrich Hobbahn

- A 48/09 Johann Albrecht Mez

- A 48/11 Franz Joseph Freiherr von Remchingen

- A 48/13 Johann Theodor Scheffer

Artistic and propaganda exploitation

The rise of a Jew who grew up in the ghetto to the top of court society was an unprecedented event until the 18th century. Jews were set tight barriers. Only by giving up their faith was it possible for them to break out of these boundaries. Oppenheimer succeeded in the previously impossible, which made his story interesting early on and made the subject of many publications. But the triumph of deeply rooted anti-Judaism and anti-Semitic sexual fantasies also served as models for the reception.

19th century

In 1827 the novella Jud Suss by Wilhelm Hauff appeared , which had to rely largely on hearsay and interpretation, as the trial files were only accessible from 1919. Hauff advocated the separation between “Jews” and “non-Jews”, but rejected the judgment as being unjust.

In 1848 Albert Dulk developed the drama Lea from and at the same time against Hauff's novella, which sided with the Jewish emancipation . In the years 1872 and 1886, with the novels by Marcus Lehmann , Suess Oppenheimer , and Salomon Kohn , Ein deutscher Minister , "erotically colored" holy kitsch "".

20th century

In Fritz Runge's 1912 play Jud Suss , Oppenheimer was a “moral thug to the taste of the anti-Semites”.

Lion Feuchtwanger's novel Jud Süß from 1925, which also does not save with drastic love scenes, became world famous . Feuchtwanger's 1918 play of the same name had received far less public response. An Anglo-American film production by Lothar Mendes Jew Süss built on the novel in 1934 , in which Oppenheimer becomes a climber in the sense of the self- made man who hopes to free his people from the ghetto. It was an attempt to warn against anti-Semitism in the newly established “Third Reich” . The film was banned in Germany and Austria.

In anti-Semitic Handbook of the Jewish question of Theodor Fritsch Joseph Suss Oppenheimer was highlighted with the words: "Among the, factors ',' agents ', residents' German princes stuck out [...] especially the Mannheim moneylenders Suss Oppenheimer , who from 1732 to In 1737 he served Duke Karl Alexander von Württemberg and fought against the old class with ducal absolutism. "

In 1933 Eugen Ortner worked on the material for the stage in line with the National Socialist conception of culture. Like Karl Otto Schilling's radio opera from 1937, the piece was based on Wilhelm Hauff's novella.

During the National Socialist era , only the anti-Semitic UFA (or Terra ) propaganda film Jud Suss , which Veit Harlan made and which premiered in 1940, was known. The film was partly based on the Hauff novella. As a compulsory program for the SS as well as for all leaders and guards in the German extermination camps, the film was primarily intended to remove remaining scruples and inhibitions in the persecution and murder of Jewish people. Eberhard Wolfgang Möller and Ludwig Metzger were involved in the script . Veit Harlan let his Jew Suss live in Frankfurt's Judengasse , a ghetto that underlined the negative clichés of National Socialism with crowded narrowness, dirt and rubbish . In 1941, Ufa-Buchverlag Berlin published JR George's novel on the film "with 16 images from the Terra film of the same name".

21st century

The opera Joseph Süß by Detlev Glanert , which premiered in 1999, processes the historical events and tells the story from the perspective of Oppenheimer, who is awaiting execution.

Jud Suess - Film Without a Conscience is a film biography from 2010 by the German director Oskar Roehler . The film deals with the making of the anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Süss , and thus indirectly the reception of Suss in the Third Reich.

In 2013, the play Der Kaufmann von Stuttgart by Joshua Sobol , directed by Manfred Langner, premiered in the Alten Schauspielhaus in Stuttgart. Here Oppenheimer is portrayed as a visionary, capitalist free thinker who fails because of the resistance of the guilds to his reforms.

Since 2013, a group of cultural workers has been initiating a series of events at Joseph Süss Oppenheimer's execution site, the Stuttgart Galgenbuckel, which deals with the location, its history and the current changes in its surroundings.

On November 7, 2013, on the occasion of the 275th anniversary of the execution, the state parliament of Baden-Württemberg held a commemorative event to commemorate the injustice committed against Joseph Süß Oppenheimer.

The exhibition rehabilitatio by the artist René Blättermann was presented as part of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in the Protestant church district of Überlingen-Stockach in the monastery and palace of Salem on October 31, 2017 .

Honors

In 1998, at the suggestion of the Geißstrasse Sieben Foundation and in the presence of Ignatz Bubis, then Chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, a square in downtown Stuttgart was named after Josef Süss Oppenheimer.

Since 2015, in memory of Joseph Süßkind Oppenheimer, the State Parliament of Baden-Württemberg and the Israelite Religious Community of Württemberg (IRGW) have jointly presented the "Joseph-Ben-Issachar-Süßkind-Oppenheimer Award" for outstanding commitment to anti-minority and prejudice in science and Journalism ”awarded. The first prize winner is the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, registered in Heidelberg .

Novels and short stories (selection)

- Wilhelm Hauff : Jud Suss . In: Wilhelm Hauff: Novellen , Volume 2. Franckh, Stuttgart 1828 (New edition: Winkler, Darmstadt 1984, ISBN 3-538-06201-3 )

- Lion Feuchtwanger : Jud Süß , Drei Masken-Verlag, Munich 1925 (new edition: Aufbau, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-351-01660-3 )

- Rolf Schneider : Süß and Dreyfus , Steidl, Göttingen 1991, ISBN 3-88243-199-7

- Hellmut G. Haasis : Joseph Süß Oppenheimer's Rache , short story, Gollenstein Verlag, Blieskastel 1994

Movie

- Jew Süss (based on the novel by Lion Feuchtwanger), 1934 (director: Lothar Mendes )

- Jud Süß (National Socialist propaganda film ), 1940 (Director: Veit Harlan )

- Joseph Süß-Oppenheimer , documentary television film on ZDF, Germany 1983, with Jörg Pleva and Manfred Krug

- Jud Süß - A film as a crime? , Docu-drama, Germany 2001, with Axel Milberg , (director: Horst Königstein)

- Jud Süß - Film Without a Conscience , Feature Film, 2010 (Director: Oskar Roehler )

- The Oppenheimer Files , Documentation, 2017 (Direction and Production: Ina Knobloch)

literature

- Manfred Zimmermann: Josef Süss Oppenheimer, a financier of the 18th century. A piece of absolutism and Jesuit history. According to the defense files and the writings of contemporaries. Riegersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1874 Digitized in the Freimann collection

- Curt Elwenspoek : Jud Suss Oppenheimer. The great financier and gallant adventurer of the 18th century. First representation based on all files, documents and records. Süddeutsches Verlagshaus, Stuttgart 1926 Digitized in the Freimann Collection .

- Peter Baumgart : Oppenheimer, Joseph Suess. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , p. 571 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Gudrun Emberger: Joseph Suess Oppenheimer. From favorite to scapegoat. In: House of History Baden-Württemberg in connection with the state capital Stuttgart (Hrsg.): Political prisoners in southwest Germany (= Stuttgart Symposion 9). Silberburg, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-87407-382-3 , pp. 31-52.

- Barbara Gerber: Jud Suess. Rise and Fall in the Early 18th Century. A contribution to historical anti-Semitism and reception research (= Hamburg contributions to the history of German Jews 16). Christians, Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-7672-1112-2 (also dissertation at the University of Hamburg , 1988).

- Hellmut G. Haasis : Joseph Suss Oppenheimer, called Jud Suss. Financier, free thinker, victim of justice ( rororo non-fiction book 61133). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-499-61133-3 .

- Hellmut G. Haasis, Ursula Reuter; Volker Gallé (ed.): Joseph Süss Oppenheimer - a judicial murder. Historical studies on the situation of the Jews in the southwest and the court Jews in the 18th century. Documentation of the scientific symposium of the city of Worms on September 12, 2009 , Worms-Verlag, Worms 2010, ISBN 978-3-936118-73-5

- Hellmut G. Haasis: memorial book for Joseph Suss Oppenheimer. With the Hebrew memorial sheet by Salomon Schächter, translated and the new Hebrew sentence by Yair Mintzker (Princeton University), Worms Verlag 2012, ISBN 978-3-936118-85-8 .

- Hellmut G. Haasis: Joseph Suss Oppenheimer's revenge. Story, biographical essay, documents from prison and the trial. With illustrations by Jona Mach (Jerusalem) and historical engravings. Gollenstein, Blieskastel 1994, ISBN 3-930008-04-1 .

- Utz Jeggle : Jewish villages in Württemberg , Tübingen 1969 (= people's life; 23).

- Robert Kretzschmar , Gudrun Emberger (Ed.): Let the sources speak. The criminal trial against Joseph Suess Oppenheimer 1737/38. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-17-020987-9 .

- Jörg Koch: Joseph Suess Oppenheimer, called "Jud Suess". Its history in literature, film and theater. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24652-6 .

- Yair Mintzker: The Many Deaths of Jud Süss. The Notorious Trial and Execution of an Eighteenth-Century Court Jew , Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford 2017, ISBN 978-0-691-17232-3 .

- Alexandra Przyrembel , Jörg Schönert (Ed.): "Jud Süss". Court Jew, literary figure, anti-Semitic caricature. Campus, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2006, ISBN 3-593-37987-2 (See web links: Conference report Hamburg 2004, conference proceedings) In particular, also via Hauff.

- Selma Stern : Jud Süß. A contribution to German and Jewish history. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1929 (= publications of the Academy for the Science of Judaism. Historical Section 6, ZDB -ID 566687-9 ) [Unchanged new edition = 2nd edition: Müller, Munich 1973].

- Aron Dancer : The History of the Jews in Württemberg. J. Kauffmann , Frankfurt am Main 1937.

- Thomas Marchart, Stefan Suppanschitz: SYN Reflexive: Thinking history. LIT Verlag Münster, 2011, section by Matthias Georg Jodl: Staged Ewigkeitswerte, pp. 43–60.

- Daniel Jütte: The Age of Mystery: Jews, Christians and the Economy of the Secret (1400–1800). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012 ISBN 978-3-647-30027-6 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Joseph Süss Oppenheimer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sweet Oppenheimer. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 41, Leipzig 1744, columns 157-165.

- Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg: Confiscated correspondence. The criminal trial against Joseph Suess Oppenheimer 1737/38

- The anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Suess

- Hetzblatt from 1738 in the Freimann Collection

- Conference report from July 2004 in Hamburg "On the power of an iconic figure"

- Exhibition Jud Süß stories of a character

- The defense letter for Joseph Suess Oppenheimer.

- Hellmut G. Haasis: Joseph Suess Oppenheimer vulgo "Jud Suess".

- Kathrin Zeilmann: Jud Süß. The biography behind the film. In: Focus online and print, 23 September 2010.

- Robert Kretzschmar: Joseph Süß Oppenheimer (1698–1738) , published on April 19, 2018 in: Stadtarchiv Stuttgart: Stadtlexikon Stuttgart .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Focus Online : Jud Suss - The Duke and the dear money - A slave in golden chains

- ↑ a b Selma Stern u. Marina Sassenberg: The Court Jew in the Age of Absolutism , Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2001, p. 241 (= series of scientific papers of the Leo Baeck Institute , 64)

- ↑ Robert Kretzschmar, Gudrun Emberger: Let the sources speak: The criminal trial against Joseph Suess Oppenheimer 1737/38 , Stuttgart, Kohlhammer 2009

- ↑ Hellmut G. Haasis: Joseph Suss Oppenheimer, called Jud Suss. Financier, Freethinker, Justice Victim , Reinbek, Rowohlt 1998, p. 341

- ↑ - ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bettina Wieselmann: The death sentence was certain. ( Memento from 7 July 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: Südwest-Presse , 8 June 2011

- ↑ www.landesarchiv-bw.de

- ↑ Jost Auler (2008): Richtstättenarchäologie 2 Books on Demand, ISBN 3-938473-12-6 Google book excerpt

- ↑ Inventory overview A48 Old Württemberg Archive of the Baden-Württemberg State Archive

- ↑ Template for “Jud Suss”: Find confirms judicial murder of the Jew Oppenheimer . In: "Die Welt", June 7, 2011

- ↑ Anat Feinberg : "Because I am a Jew". Albert Dulks Lea , in: Hans-Peter Bayerdörfer, Jens Malte Fischer (Ed.): Jews roles. Forms of representation in European theater from the restoration to the interwar period . Tübingen 2008, pp. 89 - 100 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Friedrich Knilli : Thirty years of teaching and research on the media history of "Jud Süß". A report. In: Alexandra Przyrembel, Jörg Schönert (Ed.): "Jud Süß". Court Jew, literary figure, anti-Semitic caricature. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2006, p. 75 ff.

- ^ Fritz Runge: Jud Suss. A play. Verlag von J. Kaufmann, Frankfurt a. M. 1912.

- ↑ Friedrich Knilli : Thirty years of teaching and research on the media history of "Jud Süß". A report. In: Alexandra Przyrembel, Jörg Schönert (Hrsg.): "Jud Süß" Court Jew, literary figure, anti-Semitic caricature. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2006, p. 75 ff.

- ^ Theodor Fritsch: Handbuch der Judenfrage. The most important facts for judging the Jewish people. 41st edition, Hammer-Verlag, Leipzig 1937, p. 174.

- ^ Lexicon history Baden + Württemberg on Süss-Oppenheimer ( Memento from May 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Altes Schauspielhaus Stuttgart ( Memento from September 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Information about the play; Retrieved June 5, 2013

- ↑ http://galgenbuckel.bplaced.net/wordpress/

- ↑ State Parliament of Baden-Württemberg: Memorial event on the occasion of the 275th anniversary of the execution of Joseph Süss Oppenheimer. In: landtag-bw.de. State Parliament of Baden-Württemberg, November 7, 2013, accessed on November 3, 2017 .

- ↑ REHABILITATIO - A TRIPTYCH AND TWELVE PICTURES BY RENÉ BLÄTTERMANN INSPIRED BY LION FEUCHTWANGER'S ROMAN JUD SÜSS. Retrieved November 3, 2017 .

- ^ "Südwestpresse", October 17, 1998

- ^ Hellmut G. Haasis : Stuttgart judicial murder . In: "Context: weekly newspaper", October 30, 2013

- ↑ Amadeu Antonio Foundation receives award SWR.de, August 25, 2015

- ↑ Lionel Richard: Changes of a historical figure: The Jew Suss . In: "Le Monde diplomatique", No. 6549, September 14, 2001, p. 23. German by Edgar Peinelt, haGalil onLine, September 4, 2001

- ↑ The chapter is not closed in FAZ from December 15, 2017, page 15

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Oppenheimer, Joseph Suess |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Oppenheimer, Joseph Ben Issachar Susskind |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German finance broker and banker |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 1698 or March 1698 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Heidelberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 4, 1738 |

| Place of death | Stuttgart |