Battle on the Plains of Abraham

| date | September 13, 1759 |

|---|---|

| place | Quebec |

| output | British victory |

| consequences | British occupation of Quebec |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 4800 regular soldiers | 2000 regular soldiers 600 colonial soldiers 1800 militias and indigenous people |

| losses | |

|

658 men |

644 men |

European theater of war:

Pirna * - Lobositz * - Prague * - Kolin * - Hastenbeck ** - Groß-Jägersdorf * - Moys * - Hastenbeck * - Roßbach * - Breslau * - Leuthen * - Rheinberg ** - Krefeld ** - Domstadtl * - Olomouc * - More ** - Zorndorf * - Saint-Cast - Hochkirch * - Bergen ** - Kay * - Minden ** - Kunersdorf * - Lagos *** - Hoyerswerda * - Bay of Quiberon *** - Maxen * - Koßdorf * - Landeshut * - Emsdorf ** - Warburg ** - Liegnitz * - Berlin * - Kampen Monastery ** - Torgau * - Döbeln * - Vellinghausen ** - Ölper ** - Burkersdorf * - Reichenbach * - Freiberg *

(* Third Silesian War , ** western theater of war - Great Britain / Kur-Hanover and other allies against France , *** naval battle )

American theater:

Seven Years War in North America

Monongahela - Carillon - La Belle Famille - Québec - Beauport - Abraham Plain - Sainte-Foy - Restigouche

Asian theater:

Cuddalore - Negapatam - Pondicherry - Wandiwash - Manila

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham was a battle of the Seven Years' War , also known as the French and Indian War on the North American scene . It took place on September 13, 1759 near the city of Québec in what is now Canada . British and French troops faced each other on the Abraham Plain , a high plateau just southwest of the city walls of Québec . Although fewer than 10,000 men were involved in the battle, this turned out to be a decisive event in the conflict over the rule of New France and later had an impact on the formation of Canada.

The actual battle lasted only about 15 minutes, but it was the culmination of the two and a half month siege of Québec by the British Army and Navy. The British, under the command of General James Wolfe , successfully withstood a sortie attack by French troops and Canadian militias under General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm . They employed new tactics that proved extremely effective against standard military formations such as those used in most major European conflicts. Both generals were fatally wounded during the battle. Wolfe was hit by three bullets and died minutes after the battle began; A day later, Montcalm succumbed to his injuries sustained by a musket ball.

As a result of the battle, the French gave up the city and their remaining troops in North America came under increasing pressure from the British. Although the French continued to fight after the conquest of Québec and retained the upper hand in some skirmishes, the British no longer gave up the strategically important city. With the Peace of Paris in 1763 , most of the French territories in eastern North America passed into British possession.

siege

In 1758 the British took the fortress Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island , Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley and Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario . The French were encircled, but were initially able to stop the complete conquest of New France with the victory in the Battle of Fort Carillon . The British blockade of the Saint Lawrence River during the winter proved to be a failure , as numerous French ships managed to deliver supplies to Québec. In May 1759, the French began to evacuate the population and to entrench themselves. On June 26, the British fleet landed in the vicinity of Québec, whereupon the soldiers occupied the Île d'Orléans and set up the main camp there. A French attack on the fleet with fire failed. The following day, the British also occupied the south bank of the Saint Lawrence River and began building artillery batteries .

British artillery bombardment from across the bank began on July 12 and continued unabated for the next two months. The heavy shelling, which the French had little to counter, took place mainly at night and caused great damage in the city. Numerous buildings, including the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral and the Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church , fell in flames. On July 31, General James Wolfe attempted a first serious attack on the north bank. The British landed at Beauport but were repulsed by the French. In total, this Battle of Beauport resulted in 443 losses on the British and 60 losses on the French side. In retaliation, Wolfe ordered the demolition of all the houses in a dozen kilometers long stretch along the south bank of the Saint Lawrence River, also northeast of Beauport. While this action was in progress, he drafted new plans of attack and rejected them again. He had to interrupt his work in August due to a prolonged period of illness.

Preparations and landing

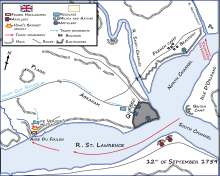

At the end of August, Wolfe and his brigadiers agreed to cross the St. Lawrence River west of the city. Numerous soldiers had already boarded the ships and drifted up and down the river for several days when Wolfe made the final decision on September 12th and his choice of landing site was Anse au Foulon. This small bay is located southwest of the town near Sillery , about three kilometers from Cap Diamant . It is located at the foot of a 53 meter high rock wall that merges into the plateau above; At that time it was protected by a cannon battery . It is not known why Wolfe chose this site, as the landing was originally intended to be further upstream. There the British could have set up a landing head and acted against the troops of Louis Antoine de Bougainville lying further west in order to lure Louis-Joseph de Montcalm out of the city and onto the high plateau. Brigadier George Townshend said the general changed his mind based on scout reports. In his last letter, dated September 12th at 8:30 p.m. on the HMS Sutherland, Wolfe wrote:

“I had the honor to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and ability, I have fixed upon that spot where we can act with most force and are most likely to succeed. If I am mistaken I am sorry for it and must be answerable to His Majesty and the public for the consequences. "

“I had the honor to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and belief, I have chosen the position where we can act with the greatest strength and where we are most likely to be successful. Should I be wrong, I am sorry and I will have to bear responsibility for the consequences to His Majesty and the public. "

Wolfe's plan of attack depended on secrecy and surprise. A small group was to go ashore on the north bank at night, climb the steep slope, occupy a small road, and overpower the garrison standing guard there. The majority of the army (5000 men) was supposed to overcome the slope via the small road and then form on the high plateau. Even if the first group were successful and the army succeeded in following them, their troops would be placed within the French defense line, with the river as the only means of retreat. Possibly Wolfe's decision to change the landing site had less to do with a desire for secrecy and more to do with his general disdain for his brigadiers (a feeling that was mutual). Perhaps he was still suffering from the effects of his illness in the latter part of August and the opiates he was taking as pain relievers. Historian Fred Anderson believes that Wolfe ordered the attack believing the vanguard would be repulsed and that he expected to die chivalrously with his men instead of returning home in disgrace.

Bougainville, who was in charge of the defense of the vast plateau, was on the evening of September 12th with his troops further upriver at Cap Rouge and did not notice the numerous British ships floating downstream. A group of 100 militiamen, under the command of Captain Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, was charged with guarding the narrow street at Anse au Foulon that followed the banks of the Saint-Denis brook. On the night of September 13th there were probably only 40 men at their post as the others were busy collecting the harvest. Vaudreuil and others had expressed concern about the possible weakness at Anse au Foulon, but Montcalm rejected it, saying 100 men would be enough to hold off an army by sunrise. He commented: “The enemy cannot be presumed to have wings so that he crossed the river that night, disembarked, climbed the obstacle-ridden slope and climbed the walls, carrying ladders for the latter. "

Guards did see boats on the river, but awaited a French supply convoy - a plan that had been canceled without Vergor's notice. When the first boats landed, the crew was asked to identify themselves. An excellent French-speaking officer from the 78th Fraser Highlanders responded and dispelled the suspicion. The boats were a little off course. Instead of landing at the end of the road, numerous soldiers found themselves at the bottom of a slope. A group of 24 volunteers, led by William Howe , were sent out to clear the fence along the road and climb the hillside. This allowed them to emerge from behind Vergor's camp and quickly take it. Wolfe followed an hour later when he was able to use a convenient access road to get to the high plateau. When the sun rose over the Plains of Abraham , Wolfe's army had a solid base above the slope.

The battle

With the exception of Vergor's camp, the high plateau was undefended, as Vaudreuil had ordered one of the French regiments shortly before landing to go to the east side of the city. Had the immediate defenders been more numerous the British might not have managed to line up and might even have been pushed back. An officer, who usually patrolled the rocks at night, was absent that night because one of his horses had been stolen and the other two were paralyzed. The first report of the landing came from an errand boy who had fled Vergor's camp, but one of Montcalm's staff said the man was crazy, sent him away and went back to sleep. Vice Admiral Charles Saunders had carried out maneuvers off Beauport to simulate a landing operation. To this end, he fired at the bank fortifications and had boats loaded with troops (many of the soldiers were patients in the field hospitals). This drew Montcalm's attention to himself.

Montcalm was stunned to learn of the British landing operation and his reaction was described as hasty. He could have waited for reinforcements from Bougainville's column, which would have allowed him to attack the British from the front and rear at the same time. He could also have avoided the battle while concentrating his troops. Instead, he decided to attack Wolfe's forces directly. Had he waited, the British would have been completely cut off - they would have come under fire on the entire way back to Anse au Foulon. To an artillery officer named Montbelliard, Montcalm explained his decision as follows: “We cannot avoid intervention; the enemy is holed up, he already has two cannons. If we give him time to settle down, we'll never have the opportunity to attack him with the troops we have. "

First battles

A total of 13,390 regular soldiers, marines and militiamen were available to Montcalm in Québec and in the shore area of Beauport, plus 200 cavalrymen, 200 artillerymen, 300 Indian warriors (including numerous Odawa under Charles Michel de Langlade ) and 140 Acadian volunteers . However, most of these troops were not involved in the fighting. Many militiamen were inexperienced; the Acadians, Canadians, and Native Americans were more familiar with guerrilla warfare . In contrast, almost all of the British were regular soldiers.

On the morning of September 13, Wolfe's army lined up with their backs to the river. She then swarmed over the high plateau, with the right flank on the steep slope parallel to the St. Lawrence River and with the left flank on a steep slope above the valley of the Rivière Saint-Charles . As the regular French forces approached from Beauport and Québec, Canadian and Native American snipers fired on the British left flank from trees and bushes. The militias held their positions throughout the battle and fell back from there during the general retreat; finally they held the bridge over the Rivière Saint-Charles.

Around 3,300 British soldiers formed a flat horseshoe formation that stretched across the entire width of the plateau; the main line of fire was about a kilometer long. To cover the entire high plateau, Wolfe had to arrange his soldiers two rows deep (instead of the usual three rows). On the left wing, regiments under Townshend fought an exchange of fire with the militia in the bushes and took several houses and a flour mill to anchor the line. The defenders drove the British away from one of the houses but were repulsed, whereupon they set several houses on fire so as not to let them fall into the hands of the enemy. The rising smoke obscured the British left flank and possibly contributed to Montcalm's misjudging the width of the line. As Wolfe's men waited for the defenders to arrive, the fire grew so bad that he ordered them to lie down in the tall grass and bushes.

When the French troops arrived from Beauport, Montcalm (one of the few mounted men in the field) decided that a swift attack was the only way to drive the British from their position. Accordingly, he raised the troops available in and near Québec and prepared an immediate attack without waiting for further reinforcements from Beauport. He arranged the roughly 3,500 soldiers: the best regular soldiers in three rows, others in six rows and the worst regiment in a column. At 10 o'clock, Montcalm ordered a general advance towards the British line. Sitting on his black horse, he waved his sword to encourage the men.

As a European-trained military leader, Montcalm relied on large, standardized battle formations in which regiments and soldiers moved in precise order. Such an approach required disciplined troops who had been painstakingly drilled for months in the parade ground to march to the beat, change formations on one word, and hold together in the face of rifle volleys and bayonet assaults. The regular regiments (the troupes de terre or metropolitains ) were used to this formal warfare, but in the course of the campaign their ranks were supplemented with less professional militiamen, whose talents as guerrilla fighters emphasized the individual. They tended to fire early and drop to the ground to reload, reducing the effect of concentrated fire at close range.

Crucial combat operations

When the French approached, the British lines held back. Wolfe had developed a firing method in 1755 to stop French column advances. For this purpose, the center, consisting of the 43rd and 47th Infantry Regiments, waited until the advancing French had approached to about 30 meters and opened fire massively at a short distance. Both armies waited about two to three minutes before the French finally fired two disorderly volleys. Wolfe had instructed his soldiers to double-load their muskets in preparation for this battle . After their first volley, the British lines advanced a few meters and fired a second volley at the French. The subsequent attack with bayonets attached wearied the French and forced them to retreat.

Wolfe, who was stationed with the 28th Regiment and the Louisbourg Grenadiers, had gone to a hill to watch the battle. He had been hit in the wrist at the beginning of the fight, but had bandaged the wound and carried on. James Henderson of the Louisbourg Grenadiers had been assigned to hold the hill and then reported that Wolfe was hit by two bullets moments after the order to fire. The first hit the epigastric region, the second (ultimately fatal) the chest. According to Knox, one of the soldiers near Wolfes shouted: "They're running, see how they're running!" Lying on the ground, Wolfe opened his eyes and asked who was running. When he learned that the French were fleeing, he issued several orders. He turned on his side and said, "Now, bless God, I will die in peace." Soon after, he succumbed to his injuries.

With Wolfe dead and several key officers wounded, the pursuit of the retreating French was disorganized. The 78th Regiment (Fraser Highlanders) was ordered by Brigadier James Murray to run after the French with swords drawn. Near the city wall , however, they got caught in the fire of a battery that covered the bridge over the Rivière Saint-Charles; They were also attacked by militiamen who remained in the trees. The 78th regiment suffered the highest losses of any British unit in battle. Townshend took command and saw Bougainville approaching from Cap Rouge behind them. He quickly formed two battalions and sent them to meet the advancing French. Bougainville withdrew as Montcalm's army crossed the Rivière Saint-Charles. Ultimately, it was Townshend's maneuver that secured British victory.

During the retreat, the still mounted Montcalm was hit either by a grape shot from the British artillery or by repeated musket fire. He suffered injuries to his abdomen and hip. He made it back to town, but his wounds were fatal and he died early the next morning. Montcalm was buried in a shell crater in the floor of the Ursuline Chapel (in 2001 his remains were transferred to the cemetery of the Hôpital général de Québec ). The battle resulted in a similar number of casualties on both sides: 644 French were killed or wounded, while the British counted 658 dead and wounded.

consequences

As a result of the battle, confusion spread among French troops. Governor de Vaudreuil, who later blamed the late Montcalm for the defeat in a letter to the government, decided to give up Québec and the shore area of Beauport. He ordered all of his troops to march west, eventually joining Bougainville. He left the garrison in Québec under the command of Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay .

First under Townshend's command and later under Murray, the British set out to besiege the now surrounded city together with Saunders' fleet. Five days later, on September 18, the French garrison surrendered, whereupon Ramezay, Townshend and Saunders signed the surrender agreement. In it, the British pledged to protect the civilian population and their property and to guarantee the free practice of religion by Catholics . The remaining French troops positioned themselves west of the city on the Rivière Jacques-Cartier .

The British fleet was forced to leave Québec as the river began to freeze over. Before the ice melted in April, François-Gaston de Lévis , Montcalm's successor, marched to Québec with around 7,000 soldiers. The British, under the command of James Murray, were weakened, with several hundred soldiers dying of scurvy during the winter . On April 28, 1760, Lévis' troops defeated the British at the Battle of Sainte-Foy . This battle was more costly than that on the Abraham level. The British were defeated, but managed to retreat behind the city walls. The shortage of artillery and ammunition, as well as improvements to the defenses made it impossible for the French to take the city before the re-arrival of the British fleet in mid-May. The sea battle in the Bay of Quiberon off the coast of France led to the destruction of the French fleet, so that no more supplies could get to New France. On September 8, the remaining French troops bowed to the overwhelming British forces near Montreal and capitulated. With the Peace of Paris in 1763 , France had to cede its holdings in North America.

memory

Most of the banks of Anse au Foulon, where William Howe and his men climbed the slope on the morning of the battle, is now an industrial zone. The Abraham level was about overbuilt to two-thirds; The side facing the St. Lawrence River has been preserved in its natural state. In the Montcalm district is the Parc des Braves , where a memorial commemorates the battle of Sainte-Foy that took place there in 1760 . The Abraham Plain and the Parc des Braves are administered by a commission of the Canadian federal government under the collective name Parc des Champs-de-Bataille ("Battlefield Park "); both are therefore considered to be urban national parks.

Large celebrations and military parades were planned for 1909 to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, which caused unease among French Canadians. They feared the celebrations would degenerate into a jubilee event for the British Empire . Political pressure from Québec meant that the celebrations were postponed by a year and instead dedicated to the 300th anniversary of the founding of the city by Samuel de Champlain .

In 2009, the National Battlefield Commission planned a re-enactment of the battles on the Plains of Abraham and at Sainte-Foy for the 250th anniversary . Leading separatist politicians described the planned event as a "slap in the face of all Québecans of French descent" and as an "insult to the Francophone majority". Individual groups threatened to use force, whereupon the commission canceled the event.

literature

- Fred Anderson: Crucible of War. The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Alfred A. Knopf, New York NY 2000, ISBN 0-375-40642-5 .

- Rene Chartrand: Québec. The heights of Abraham 1759. The armies of Wolfe and Montcalm (= Order of Battle Series 3). Osprey Military, Oxford 1999, ISBN 1-85532-847-X .

- R. Douglas Francis, Richard Jones, Donald B. Smith: Origins. Canadian History to Confederation. 4th edition. Harcourt Canada, Toronto et al. 2000, ISBN 0-7747-3664-X .

- Derek Hayes: Historical Atlas of Canada. Canada's History illustrated with original maps. Douglas & McIntyre Ltd., Vancouver et al. 2002, ISBN 1-55054-918-9 .

- Franz Herre : The American Revolution. Birth of a world power. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1976, ISBN 3-462-01124-3 .

- Peter Macload: Vérité sur les plaines d'Abraham. Les huit minutes de tirs d'artillerie qui ont façonné un continent. Les èditions de l'Homme, Montréal 2008, ISBN 978-2-7619-2575-4 .

- Stuart Reid: Quebec 1759. The Battle That Won Canada (= Campaign 121). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2003, ISBN 1-85532-605-1 .

- Mark Zuehlke: The Canadian military atlas. The Nation's battlefields from the French and Indian Wars to Kosovo. Stoddart Publishing, Toronto 2001, ISBN 0-7737-3289-6 .

Web links

- National Battlefield Commission (English, French)

- Battle of the Plains of Abraham , article in the Canadian Encyclopedia (English, French)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hibbert: Wolfe At Quebec . P. 125.

- ↑ Hibbert: Wolfe At Quebec . P. 121.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 117.

- ↑ Anderson: Crucible of War. P. 353.

- ↑ Anderson: Crucible of War. Pp. 354, 789.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 103.

- ↑ Casgrain: Wolfe And Montcalm. P. 164.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 55.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 37.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 125.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. Pp. 58-61.

- ^ Eccles: France in America. P. 123.

- ↑ Anderson: Crucible of War. Pp. 355-356.

- ↑ Anderson: Crucible of War. P. 359.

- ^ Eccles: France in America. Pp. 203-204.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. Pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Casgrain: Wolfe And Montcalm. P. 117.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 61.

- ↑ Hibbert: Wolfe At Quebec. P. 148.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 69.

- ↑ Chartrand: Quebec 1759, p. 86.

- ^ Eccles: France in America. P. 197.

- ^ A b Eccles: France in America. P. 182.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. Pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Hibbert: Wolfe At Quebec. P. 151.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 139.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. Pp. 76-77.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 82.

- ↑ Anderson: Crucible of War. P. 363.

- ↑ Chartrand: Quebec 1759. P. 90.

- ↑ Chartrand: Quebec 1759, p. 94.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. P. 83.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 149.

- ^ Lloyd: The Capture of Quebec. P. 142.

- ^ Reid: Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. Pp. 74-75.

- ^ Francis et al .: Origins: Canadian History to Confederation. P. 142.

- ↑ Au cœur de Québec, le parc des Champs-de-Bataille. Commission des champs de batailles nationaux, June 17, 2013, accessed on November 17, 2014 (French).

- ^ Jean-Marie Lebel, Alain Roy: Québec 1900–2000, le siècle d'une capitale . Éditions Multimondes, Québec 2000, ISBN 2-89544-008-5 , pp. 14-15 .

- ^ Organizers cancel mock Battle of the Plains of Abraham. CBC News , February 17, 2009, accessed November 17, 2014 .