Singapore strategy

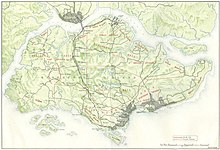

The Singapore Strategy was a strategy pursued by the British Empire between 1919 and 1941. It consisted of a series of strategic plans developed over a period of twenty years with the aim of preventing the Japanese Empire from attacking the Empire or repelling such an attack by moving a Royal Navy fleet to the Far East can. Ideally, this fleet should be able to intercept and defeat a Japanese force advancing on Australia or British India . In order to be able to effectively implement the strategy, a well-equipped naval base, a kind of " Gibraltar of the East", was required, as the position of which the planners chose Singapore in 1919 . Singapore was strategically located on the Strait of Malacca and thus controlled the transition between the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal and thus ultimately the eastern access by sea to British India, the largest and most important possession of the British Empire. The expansion of the naval base and its defenses dragged on over the next two decades.

The planners envisaged three phases for a war against Japan: While the garrison forces were defending the fortress Singapore, strong naval formations from British waters would move towards Singapore and set out from there to relieve or retake the crown colony of Hong Kong . They would then set up a sea blockade against the main Japanese islands to force the Japanese government to accept British peace terms. The idea of an amphibious invasion of Japan was rejected as impracticable. Rather, the naval planners reckoned that the Japanese Navy would not seek a decisive battle against a superior naval force and, based on their own experience as an island nation, believed the economic effects of a blockade would be sufficient to exert the necessary pressure on Japan.

The Singapore Strategy formed the cornerstone of Britain's defense strategy for the Far East in the 1920s and 1930s, with strategic planning increasingly becoming dogma . However, a combination of financial, political and practical problems made the strategy unfeasible. It came under increasing criticism within the Empire in the 1930s, particularly in Australia, where it served as a pretext for low defense spending. In the Second World War , the Singapore strategy finally led to the deployment of Force Z to Singapore. The sinking of the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse by Japanese naval aviators on December 10, 1941 and the subsequent surrender of Singapore , which was perceived as shameful, described Winston Churchill as "the worst disaster and the greatest surrender in British history".

Origins

With the self-sinking of the Imperial High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow after the First World War , a potentially equal opponent of the Royal Navy had been eliminated; The expanding navies of the United States and the Japanese Empire increasingly threatened the status of the Royal Navy as the most powerful navy in the world. The decision by the United States to create what Admiral of the Navy George Dewey said was "unmatched" suggested a new maritime arms race .

In 1919, the Royal Navy was still the largest navy in the world. However, by continuing to build the more modern warships laid down in the United States during World War I, the US Navy gained a technological edge. The maxim of the " two-power standard " of 1889 stated that the Royal Navy had to be strong enough to be able to withstand any combination of two other navies. In 1909, politics reduced this requirement to a sixty percent superiority with the dreadnoughts . Growing tensions over the continued American construction program led to heated discussions between First Sea Lord Rosslyn Wemyss and Chief of Naval Operations William S. Benson in March and April 1919 , despite a 1909 directive by the British government that the United States was not considered potential opponents are to be considered. The British Cabinet upheld this policy in August 1919 to prevent the Admiralty from demanding a similar one for the Royal Navy due to the American construction program. In 1920 the First Lord of the Admiralty Walter Long proclaimed a "one-power standard" according to which the Royal Navy should be "not [...] of less strength than the navy of any other power". The “one-power standard” became the official guideline through its public announcement at the 1921 Reich Conference.

The Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominions met at the Imperial Conference of 1921 to agree on a common foreign policy, particularly towards the United States and Japan. The most pressing question was whether the Anglo-Japanese alliance , which expired on July 13, 1921 , should be extended. The strongest advocates of an extension were the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand, Billy Hughes and William Massey , who wanted to prevent their countries from getting caught between the front lines in a war between the United States and Japan. They pointed to the generous support Japan had given during World War I. In contrast, the United States withdrew from international politics after the war. “The British Empire,” said Hughes, “must have a reliable partner in the Pacific ". Canadian Prime Minister Arthur Meighen , on the other hand, declined an extension because it would negatively affect relations with the United States, which Canada relied on for its protection. As a result, the conference participants could not agree on the question of the extension, so that the alliance contract expired on July 21 of that year.

The Washington Naval Conference of 1922 established a ratio of 5: 5: 3 for the naval strengths of the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan. As a result, the Royal Navy remained the largest navy in the world until the late 1920s, keeping the navy of Japan, considered the most likely adversary, at bay. The Washington Naval Agreement also banned the fortification of Pacific islands, but Singapore explicitly exempted from this ban. The 1930 London Fleet Treaty limited the construction of warships, which the British shipbuilding industry suffered. The refusal of the German Reich , continued in the Treaty of Versailles laid down arms limitations observed for the size of its navy, led in 1935 to the British German fleet agreement . The British viewed the agreement as a sign that the German Reich was making serious efforts to avoid a conflict with the United Kingdom (before the First World War the German Empire was not prepared to impose such contractual restrictions on its naval armament). In 1934, First Sea Lord Ernle Chatfield began pushing for an armament program for the Navy in order to be able to confront Japan and the strongest European power at the same time. For this program, he planned to fully utilize the capacities of the British shipyards. The high cost of the project, estimated at £ 88 to 104 million , aroused opposition from the Treasury. It was not until 1938 that the Treasury gave up its fight against British rearmament, as both politicians and the public feared the possibility of falling into a war with Germany or Japan unprepared rather than a possible financial crisis in the distant future caused by armaments spending.

plans

The Singapore Strategy was a series of war plans developed over twenty years in which the stationing of a fleet in Singapore was a common, but not mandatory, aspect. Both defensive and offensively oriented plans were developed. Some envisaged the overthrow of Japan, while others were designed to prevent hostilities from breaking out altogether.

In November 1918, the Australian Secretary of the Navy, Joseph Cook , asked British Admiral John Jellicoe to draft a maritime defense scheme for the Empire. In February 1919 Jellicoe went on a tour of the Empire on board the battle cruiser HMS New Zealand . In August of that year he presented a first report to the Australian government. In one section of the classified report, he concluded that the interests of the Empire and Japan would inevitably collide. As a counterweight to the Japanese Navy, he suggested the establishment of a British Pacific fleet. According to his estimates, such a fleet should have eight battleships, eight battlecruisers, four aircraft carriers, ten cruisers, 40 destroyers and 36 submarines as well as supporting ships of smaller types.

That fleet should, in Jellicoe's opinion, have large enough shipyards somewhere in the Far East. In October 1919 the Committee of Imperial Defense debated a document entitled "The Naval Situation in the Far East". In this, the Naval Staff stated that a continuation of the Anglo-Japanese alliance could lead to war between the Empire and the United States. In the following year the Admiralty presented the "War Memorandum (Eastern) 1920", which contained a series of instructions in the event of a war against Japan. The defense of Singapore has been described as "absolutely essential". The strategies of the War Memorandum were presented to the Dominions at the 1923 Reich Conference.

The authors of the memorandum divided a possible war with Japan into three phases. In the first phase, the Singapore garrison would defend the city until a fleet arrived from home waters. This would run from Singapore to Hong Kong and horror the city or, in the event of an interim conquest, recapture it from the Japanese. The third phase saw the naval blockade of Japan in order to force it to accept the British peace conditions.

The greatest planning effort was made for phase 1, which was considered the most important. For this purpose, the construction of defense systems in and around Singapore was planned. The second phase required the establishment of a naval base that was able to supply a larger fleet. While the United States had built a dry dock between 1909 and 1919 at its central Pacific base at Pearl Harbor , which was also able to accommodate battleships, the Royal Navy had not had any such facility east of Malta . In April 1919, the Admiralty's planning department prepared a report examining possible positions for such a dock in order to effectively support a war against Japan or the United States. Hong Kong was considered too vulnerable but discarded, while Sydney was considered safe but too far from Japan. In the end, Singapore remained the best compromise solution.

Estimates of how long it would take to send a fleet to Singapore after the outbreak of war varied. They had to include the time of fleet assembly and equipment as well as the time of approach to Singapore. The first estimate was 42 days, but assumed a certain warning time before the outbreak of war. In 1938 the estimates were increased to 70 days, including 14 additional days for equipping the ships. In June 1939 it was increased to 90 days and finally to 180 days in September of that year.

To support the relocation and movement of the fleet, a number of oil depots have been set up near Gibraltar , Malta, Port Said , Port Sudan , Aden , Colombo , Trincomalee , Rangoon and Hong Kong, as well as in Singapore itself. To make matters worse, the battleships could not cross the Suez Canal when their fuel bunkers were full, which meant they had to bunker new oil after the passage. Singapore was given warehouses in which 1,270,000 tons of oil could be stored. Secret bases have been set up on Kamaran , Addu Atoll and Nancowry . Estimates assume a monthly requirement of 111,000 t of oil, which would be brought to the required locations by 60 tankers . The oil refineries near Abadan and Rangoon were to serve as the source , supplemented by the entire oil production of the Dutch East Indies , which would be bought in.

Phase 3 received the least amount of attention, but naval planners found that Singapore was too far away to effectively support operations in the waters surrounding Japan. Accordingly, the clout of the fleet would decrease the further it moved from its Singapore base. In the event of American support, Manila should be used as an advanced base. The idea of invading the main Japanese islands was discarded as unrealistic. The naval planners did not expect the Japanese fleet to face a decisive battle as long as it was in the weaker position. That is why they preferred a sea blockade that was far less risky - also based on their own experience of how vulnerable an island nation based on overseas possessions was to one. They considered the economic pressure this created to be sufficient.

Studies have been conducted into Japan's vulnerability to sea blockades. Based on data provided by the Board of Trade and the Naval Attachés in Tokyo, naval planners estimated that 27% of Japanese imports came from the Empire. Most of these imports, however, could be offset by imports from China and the United States in the event of a trade embargo. They identified metals, machines, chemicals, oil and rubber as strategically most important trading goods. The Empire controlled the world's most abundant sources of some of these raw materials. The planners intended to prevent Japan's access to neutral shipping space by renting shipping space, which was intended to reduce the available capacity. Furthermore, ships going to Japan should no longer be insured.

The problem of a sea blockade that was tightly drawn around the Japanese archipelago was the wide dispersion of the ships involved, which made them vulnerable to air attacks and submarines. Blocking the Japanese ports by smaller ships was considered, but most of the Japanese fleet would have to be sunk. However, it was considered uncertain whether the Japanese could be put into a bigger battle. There were also plans for a broader blockade, in which the British fleet was supposed to arrest ships going to Japan on the Panama Canal and near the Dutch East Indies. Japan could still trade with China, under its rule Korea, and possibly the United States in implementing this plan . Accordingly, those responsible viewed such a blockade with skepticism.

Rear Admiral Herbert Richmond , East Indies Station Commander, noted that the logic of the plans was circular :

- We are forcing Japan to surrender by cutting it off from its essential raw materials.

- We cannot cut them off from their essential raw materials until we have defeated their fleet.

- We cannot beat their fleet if they do not go into battle.

- We should force their fleet into battle by cutting them off from their essential raw materials.

The 1919 plans included a Mobile Naval Base Defense Organization (MNBDO) to establish and defend an advanced base. The MNBDO consisted of an anti-aircraft brigade, a coastal artillery brigade and an infantry battalion and had a total strength of 7,000 men. These were entirely recruited from the ranks of the Royal Marines . In a simulation game, Royal Marines occupied Nakagusuku Bay on Okinawa without resistance and enabled the MNBDO to set up a base from which the British fleet blocked Japan. To test the MNBDO concept, the Navy carried out fleet exercises in the Mediterranean in the 1920s. A lack of interest on the part of the Royal Marines in amphibious warfare and the poor organizational structure for such reduced the ability to conduct amphibious operations. In the 1930s, the Admiralty expressed concern that Japan and the United States had become superior to British forces in this area. She therefore suggested the formation of the Inter-Service Training and Development Center of the Air Force, Army and Navy, which began its service in July 1938. Under his first commander, Loben Maund , research into problem areas of amphibious operations such as the construction of suitable landing vehicles began .

Amphibious operations were not the only area in which the Royal Navy lost its technical-strategic advantage during the 1930s. In the 1920s, Colonel William Forbes-Sempill led the semi-official Sempill mission to help the Japanese Navy establish its own naval aviation. At the time, the Royal Navy was the world leader in the use of naval aviators. The Sempill mission taught complicated maneuvers such as landing on the flight deck of a carrier and conducted training on modern machines. It also provided engines, weapons and technical equipment. Within a decade, Japan managed to outperform the UK in this area. The Royal Navy was the first to introduce armored flight decks, which made the carriers more resistant, but also reduced the number of aircraft that could be used. They trusted in the effectiveness of the anti-aircraft guns installed on the carriers and saw little use in stationing high-performance fighters on them. On the contrary, they developed a number of multi- role fighter jets such as the Blackburn Roc , Fairey Fulmar , Fairey Barracuda , Blackburn Skua and the Fairey Swordfish , so that the few aviators of a carrier had the widest possible range of possible uses.

The possibility that Japan might take advantage of a war breaking out in Europe was considered. The Tientsin incident of June 1939 brought another possibility into focus, namely that the German Reich might try to take advantage of a war in the Far East. In the event of the worst possible scenario, a simultaneous war against the German Reich, Italy and Japan, two options were envisaged. The first was to reduce the war to the German Empire and Japan by pushing Italy out of the war as quickly as possible. The former First Sea Lord Reginald Drax , who had been recalled from retirement, planned to send a "flying squadron" of four to five battleships, an aircraft carrier and several cruisers and destroyers to Singapore. This squadron would not have the strength to fight the Japanese fleet, but it could protect British merchant shipping in the Indian Ocean. Drax argued that a small, swift bandage could do this better than a large, clumsy one. As soon as more ships could be dispensed with, the "flying squadron" could form the core of a larger battle fleet. Lord Chatfield, meanwhile appointed Minister for Defense Coordination, rejected the concept. For him, the planned squadron was no more than a target for the Japanese fleet. He advocated abandoning the Mediterranean in the event of war and moving the entire Mediterranean fleet to Singapore.

Construction of a naval base

After prospecting, a site in Sembawang was chosen as the location for the proposed naval base. The Straits Settlements donated 1,151 hectares for this purpose and the Hong Kong Crown Colony donated £ 250,000 in 1925 . That figure exceeded the UK's £ 204,000 expense that year to build the floating dock. The Federated Malay States and New Zealand provided further sums of 2 million and £ 1 million respectively. The contract for the construction of the base went to Sir John Jackson Limited, which had submitted the cheapest offer at £ 3.7 million. The dock facilities extended over an area of 57 km² and comprised the largest dry dock and third largest floating dock in the world at the time, as well as sufficient fuel stores to supply the entire Royal Navy for six months.

To defend the base, batteries with heavy 381 mm coastal guns were set up in Changi and Buona Vista to repel attacking battleships. Medium guns of caliber 234 mm were supposed to repel smaller attacking ships. Smaller caliber batteries to repel air and ground raids were stationed at Fort Siloso , Fort Canning and Fort Pasir Panjang . The first of the 381 mm guns came from obsolete naval stocks and were built between 1903 and 1919. Part of the costs was financed by a gift of £ 500,000 that Sultan Ibrahim gave to King George V of Johor on the silver jubilee of the throne. Three of the guns had a swivel range of 360 ° and underground magazines.

In addition, the Royal Air Force stationed air units around the base. Plans envisaged an association of 18 flying boats, 18 reconnaissance fighters, 18 torpedo bombers and 18 single-seat fighter planes to protect them. For stationing, it built the airfields RAF Tengah and RAF Sembawang . The chief of the air staff , Air Marshal Hugh Trenchard noted that 30 torpedo bombers could make the heavy coastal artillery superfluous. The First Sea Lord David Beatty rejected this proposal. As a compromise, the guns should be stationed for the time being and the matter should be renegotiated if better torpedo bombers were available. Practice shooting of the 381 and 234 mm guns in Malta and Portsmouth in 1926 revealed that more advanced ammunition would be needed to have a realistic chance of hitting an attacking battleship.

The King George VI dry dock was inaugurated on February 14, 1938 by the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Shenton Thomas . Two squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm flew over the dock in celebration of the day. The 42 ships attending the inauguration included three US Navy cruisers. The presence of such a fleet was used by the military to hold a series of air and naval maneuvers. The aircraft carrier HMS Eagle was able to approach Singapore undetected up to 217 km and launched several air strikes against the airfields there. The local air commander Arthur Tedder found this failure of his aviators an embarrassment. Land Forces Commander William Dobbie also shamed the performance of his air defense. Analyzes of the maneuvers recommended the installation of radar systems on the island, but this did not happen until 1941. The naval defense did better, but could not prevent landing units disconnected from HMS Norfolk from occupying the Raffles Hotel . What worried Dobbie and Tedder most was the possibility of complete bypassing of the fleet if the enemy came over land and attacked the Straits Settlements. A maneuver ordered by Dobbie in southern Malaya proved that the jungle there was anything but impassable. The Chiefs of Staff Committee concluded that it was most likely that the Japanese would land on the east coast of Malaysia and attack Singapore from there.

Australia

The Conservative government of Stanley Bruce in Australia supported the Singapore Strategy as best it could. According to her, Australia should support the Royal Navy with a squadron that should be as strong as the country could handle. Following this guideline, the country invested £ 20 million in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) between 1923 and 1929 , while the Australian Army and defense industry totaled £ 10 million and the nascent Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) 2.4 million Received £. This policy, which was geared towards the Singapore strategy, had the advantage of being able to shift the responsibility for the defense of the country onto the British mainland. Unlike New Zealand, however, Australia did not contribute to the costs of building the Singapore Naval Base. In order to get a higher budget from the thrifty government, the Australian Army had to refute the Singapore Strategy, which was considered "an obviously well-discussed and well-founded strategic doctrine that has been affirmed at the highest level of the imperial decision-making process".

The Australian Labor Party , which was not in the opposition for only two years during the 1920s and 1930s, advocated a different policy from 1923 onwards. This stipulated that Australia's first line of defense should be strong air forces, supported by a well-equipped Australian Army, which could be greatly increased in the event of an impending invasion. However, this required a well-developed armaments industry. Labor politicians cited critics of conservative politics such as the American Rear Admiral William F. Fullam , who highlighted the vulnerability of ships to air raids, sea mines and submarines. Albert Green calculated in 1923 that if a battleship was currently £ 7 million and an airplane was £ 2,500, it must be a question of concern whether a battleship was a better investment than hundreds of airplanes when an airplane could sink a battleship. The Labor Party's policy was ultimately based on the demands of the Army.

In September 1926, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wynter gave a lecture at the Royal United Services Institute in Victoria entitled The Strategical Inter-relationship of the Navy, the Army and the Air Force: an Australian View , which appeared in the British Army Quarterly in April 1927 . In the lecture, Wynter claimed that war would be most likely to break out in the Pacific if the UK was bound by a crisis in Europe and unable to send sufficient forces to Singapore. He advocated the thesis that Singapore was vulnerable to attacks, especially from land and air, and advocated a more balanced arms policy that did not focus solely on the RAN. “Going forward,” wrote the Australian historian Lionel Wigmore, “the attitude of the leading planners of the Australian Army towards British insurance companies to send a sufficient fleet to Singapore in times of crisis has been (frankly) this: 'We do not doubt the sincerity of your convictions, but to be honest, we don't think you can. '"

Frederick Shedden wrote a thesis paper that identified the purpose of the Singapore strategy as defending Australia. He argued that, as an island nation, Australia was also vulnerable to a sea blockade. If Australia can be defeated without an invasion, its defense strategy should be a maritime one. Colonel John Lavarack , who had attended the 1928 class of Imperial Defense College with Shedden , contradicted him. He stated that Australia's long coastline made a sea blockade much more difficult and its remarkable internal resources meant that it could withstand the economic pressures of such a blockade. After Herbert Richmond attacked the Labor Party positions in the British Army Quarterly in 1933 , Lavarack penned a rebuttal.

In 1936, the Australian opposition leader John Curtin read an article by Wynters in front of the House of Representatives . Wynter's open criticism of the Singapore strategy led to his transfer to a lower post. Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities with the German Reich on September 3, 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies replaced Lavarack as Chief of the Army with the British Lieutenant General Ernest Squires . Within a few months, the Chief of Air Force had also been replaced by a British officer.

Second World War

After the outbreak of war with Germany, Menzies sent Richard Casey to London to seek reassurance on the defense of Australia in the event that Australia would send troops to Europe and the Middle East. In November, Australia and New Zealand received assurances that the fall of Singapore must be prevented at all costs and that in the event of a war with Japan, the defense of the Far East would take precedence over that of the Mediterranean. This seemed possible because the German navy was relatively small and France was available as an ally. Stanley Bruce, now Australian High Commissioner in the UK, met with members of the UK Cabinet on November 20th. After the meeting, he got the impression that, despite the reinsurance, the Royal Navy was not strong enough to deal with parallel crises in Europe, the Mediterranean and the Far East.

In the course of 1940, the situation slowly but inexorably moved towards the worst possible assumed scenario. In June Italy entered the war on the side of the German Empire and France capitulated. The Chiefs of Staff Committee reported:

“The security of our imperial interests in the Far East lies ultimately in our ability to control sea communications in the south-western Pacific, for which purpose adequate fleet must be based at Singapore. Since our previous assurances in this respect, however, the whole strategic situation has been radically altered by the French defeat. The result of this has been to alter the whole of the balance of naval strength in home waters. Formerly we were prepared to abandon the Eastern Mediterranean and dispatch a fleet to the Far East, relying on the French fleet in the Western Mediterranean to contain the Italian fleet. Now if we move the Mediterranean fleet to the Far East there is nothing to contain the Italian fleet, which will be free to operate in the Atlantic or reinforce the German fleet in home waters, using bases in north-west France. We must therefore retain in European waters sufficient naval forces to watch both the German and Italian fleets, and we cannot do this and send a fleet to the Far East. In the meantime the strategic importance to us of the Far East both for Empire security and to enable us to defeat the enemy by control of essential commodities at the source has been increased. "

“The security of our imperial interests in the Far East ultimately depends on our ability to control sea connections in the Southwest Pacific, for which an adequate fleet must be stationed in Singapore. Since our previous assurances on this matter, the whole strategic situation has changed considerably as a result of the French defeat. The result is a complete shift in maritime forces in our home waters. Previously, we were ready to abandon the eastern Mediterranean and move a fleet to the Far East, confident that the French fleet would control the Italian navy in the western Mediterranean. If we move our Mediterranean fleet to the Far East, there will be nothing to control the Italian fleet, which will then be free to operate in the Atlantic or to strengthen the German fleet in home waters and use bases in north-west France. We must therefore have sufficient naval forces in European waters to observe both the German and Italian fleets and we cannot do this and at the same time send a fleet to the Far East. In the meantime, the strategic importance of the Far East has increased both for the security of the Empire and for our ability to defeat the enemy by controlling essential goods at their source. "

The prospect of American support still existed. During secret talks in Washington, DC in June 1939, the American Chief of Naval Operations William D. Leahy had considered the possibility of sending an American fleet to Singapore. In April 1940, the American naval attaché in London, Alan G. Kirk , asked the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff, Tom Phillips , whether, if an American fleet were to be relocated to the Far East, the docks in Singapore would be available because the company's own in the Filipino Subic Bay are not sufficient for this. He received a confirmation for this. A secret staff conference in Washington, DC in February 1941 put a damper on hopes of such a move. The Americans made it clear at the conference that their focus would be in the Atlantic in the event of a war. The Royal Navy could, relieved of pressure in the Atlantic, move its own ships to the Far East.

In July 1941, Japan occupied Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina , which the Royal Navy included in their plans as an anchorage for a march north. As a result, the Japanese came within a striking range of Singapore that was uncomfortably close for the British. As interstate relations continued to deteriorate, the Admiralty and the Chiefs of Staff discussed for the first time in August 1941 which ships could move to Singapore. They decided to move the HMS Barham out of the Mediterranean first , followed by four Revenge- class battleships that were in British and American docks for overhaul. On November 25, the Barham was sunk by a torpedo hit by the German submarine U 331 in the ammunition magazine off the Egyptian coast and three weeks later an Italian commando operation severely damaged the two battleships HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Valiant, which were still in the Mediterranean . In response, the Admiralty decided to be able to send the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle in an emergency .

Winston Churchill commented on this shortage of available ships that since the German battleship Tirpitz alone binds a large British fleet, a small fleet in Singapore could have the same disproportionate effect on the Japanese. The Foreign Office believed that the presence of modern battleships in Singapore could prevent Japan from entering the war. Following this opinion, in October the Admiralty ordered the Prince of Wales to leave home waters for Singapore, where the Repulse would join them. The carrier Indomitable was supposed to join this squadron, but ran aground off Jamaica on November 3rd .

In August 1940 the chiefs of staff put the force needed to defend Malaysia and Singapore, if a fleet were not available, at 336 fighter jets and a garrison of nine brigades . Churchill renewed reassurance to the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand that in the event of attack their defense would have the highest priority, just after that of the British Home Isles. A defense conference was held in Singapore in October . Representatives from all three branches of the armed forces attended, including the Commander in Chief of China Station , Vice Admiral Geoffrey Layton , the Commanding Officer of Malaya Command , Lt. Gen. Lionel Bond and the Commanding Air Officer of the RAF in the Far East, Air Marshal John Tremayne Babington . Australia sent its branch deputy commanders in command, Sea Captain Joseph Burnett , Major General John Northcott and Air Commodore William Bostock . The conference participants discussed the situation in the Far East for ten days. They estimated the need for the successful air defense of Burma and Malaya to be at least 582 aircraft. When Japan entered the war on December 7, 1941, there were only 164 combat aircraft in Malaya and Singapore and the fighter units consisted of obsolete Brewster F2A . The land forces also had only 31 of the planned 48 infantry battalions and no tanks, although two tank regiments were planned. Furthermore, most of the units were poorly trained and poorly equipped. In contrast, the United Kingdom delivered 676 aircraft and 446 tanks to the Soviet Union between late June and late December 1941 alone .

The Japanese were aware of the state of the defense efforts in Singapore. They had spies in Singapore like British Captain Patrick Heenan . In addition, they received secret documents prepared by the German Reich in August 1940 about the situation in the Far East, which they captured when the auxiliary cruiser Atlantis attacked the SS Automedon on November 11th of that year . Some historians suspect that the detailed information obtained in this way influenced the Japanese decision to enter the war.

On December 8, 1941, Japanese troops occupied the international concessions in Shanghai and a few hours later troop landings began at Kota Bahru , an hour before the attack on Pearl Harbor . On December 10th, Japanese planes sank the Prince of Wales and the Repulse off the coast of Malaysia. After the disastrous Battle of Malaya for Commonwealth troops , Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942. During the final stages of the fighting, the 381 mm and 234 mm guns fired at targets at Johor Bahru , RAF Tengah and Bukit Timah .

aftermath

The surrender of Singapore

From February 8, 1942, Japanese troops coming from the north began to cross over to Singapore. There they succeeded in gaining space for tanks to land and consistently pushing the Commonwealth troops back south over the next few days. After repeated requests by the Japanese commander Yamashita Tomoyuki and also by his own officer corps, the British commander Arthur Percival capitulated on February 15. He acted against the order of Winston Churchill, who had categorically refused to surrender. He later described the event as "the worst disaster and the greatest surrender in British history". It represented a deep setback for British prestige and war morale. The promised fleet could not be dispatched and the fortress, which was considered to be "impregnable", fell within a short time. The British and their allies lost approximately 139,000 men, 130,000 of whom were captured. Among the 38,000 British casualties was nearly the entire 18th Infantry Division ordered to Malaya in January . 18,000 Australians, mostly from the Australian 8th Division, and 14,000 members of local troops also fell or were captured. Most of the losses were suffered by the British Indian associations with around 67,000. About 40,000 of the prisoners later joined the Indian National Army fighting on the side of the Japanese . Particularly humiliating was the fact that a numerically clearly superior British force had capitulated to the Japanese.

Richmond, in a 1942 article in The Fortnightly Review , claimed that the loss of Singapore demonstrated "the folly of inadequate preparation for control of the sea in a war that unfolded on two oceans." He argued that the Singapore strategy has always been unrealistic. The resources devoted to defending Malaya were inadequate for the defense and the way they were distributed was generally wasteful, inefficient and ineffective.

The surrender had both military and political consequences. Before the parliament, Churchill declared that after the end of the war a committee of inquiry should look into the case. The publication of the speech in 1946 led the Australian government to inquire whether such a committee of inquiry was still planned. The United Planning Staff responded to the request and stated that such an investigation was not possible. He justified his decision by stating that it was not possible to concentrate solely on the events leading directly to the surrender of Singapore. In this context, it is inevitable to examine the diplomatic, military and political aspects of the Singapore strategy over a long period of time. Prime Minister Clement Attlee heeded this recommendation and no committee of inquiry was set up.

In Australia and New Zealand, after years of appeasement, this led to a certain feeling of being betrayed by Britain. “In the end,” wrote one historian, “you can turn it around as you like, the British let you down.” This strained political relations between the countries for decades. In a speech delivered to the House of Representatives in 1992, Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating re- fueled the debate:

“I was told that I did not learn respect at school. I learned one thing: I learned about self-respect and self-regard for Australia - not about some cultural cringe to a country which decided not to defend the Malayan peninsula, not to worry about Singapore and not to give us our troops back to keep ourselves free from Japanese domination. This was the country that you people wedded yourself to, and even as it walked out on you and joined the Common Market, you were still looking for your MBEs and your knighthoods, and all the rest of the regalia that comes with it. "

“I was told that I didn't learn respect in school. I learned one thing: I learned about self-respect and self-esteem for Australia - not about cultural subservience to a country that chose not to defend the Malay Peninsula, not to care about Singapore, and to send our troops back to us could have protected us from Japanese rule. This was the country to which you submitted yourself, and even when it trampled you and turned to the European single market , you continued to hope for your MBEs , knights and all the other trappings that go with it. "

A sufficiently large fleet was necessary for the downfall of Japan. From 1944 the British Pacific Fleet was used in the Far East, where it operated together with the United States Pacific Fleet . The cooperation that began before the war against Japan and the alliance that deepened during the war represented a long-term replacement for the Singapore strategy.

The Singapore Naval Base suffered only minor damage during the battle for the city and was subsequently able to serve as the most important naval base away from the main islands by the Japanese. The British damaged their 381 mm coastal guns before the surrender, but the Japanese were able to repair all but four of the guns. In 1944 and 1945 there were repeated air raids on Singapore , which also damaged the naval base. After Japan surrendered , the British took possession of Singapore again.

Operation Mastodon

In 1957, the Singapore strategy was revived in the form of Operation Mastodon . The operation Mastoton foresaw with nuclear weapons -equipped V-bombers of the RAF Bomber Command to deploy in Singapore. These should form part of SEATO's UK defense contribution in the region. There were again logistical problems. Since the V bombers could not cover the whole distance to Singapore in one go, a new intermediate base had to be built on the Maldives with RAF Gan . Since the runway at RAF Tengah was too short for the V bombers, they had to move to RMAF Base Butterworth until Tengah's runway could be extended. The stationing of nuclear armed aircraft and additional nuclear weapons without consulting the local authorities quickly led to political complications.

The operation Mastodon saw the deployment of two squadrons of eight Handley Page Victor on Tengah and a squadron of eight Avro Vulcan prior to Butterworth. The British nuclear arsenal consisted of 53 warheads in 1958, most of them of the older Blue Danube type. In contrast, the plans of Operation Mastodon envisaged the stationing of 48 warheads of the newer, lighter Red Beard type . They were to be stored in Tengah so that every V-bomber there and in Butterworth could be loaded with two bombs. In 1960 the Royal Navy relocated the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious with Red Beards and nuclear-equipped fighter planes of the type Supermarine Scimitar to the Far East. As with the original Singapore strategy, this time too there were concerns about whether the stationed units could be adequately supplied with spare parts in the event of a crisis that required them. The concerns were particularly expressed after the detonation of the first Chinese atomic bomb in 1964.

When the Konfrontasi between Indonesia and Malaysia intensified in 1963, the Bomber Command sent squadrons from Victors and Vulcans to the Far East. For the next three years four V-bombers were permanently stationed there. The stationed squadrons alternated in turn through the corresponding squadrons. In April 1965, the No. 35 Squadron RAF made an urgent move to Butterworth and Tengah. Air Chief Marshal John Grandy reported that the V-bombers would provide an effective deterrent against waging conflict on a large scale. Political, ethnic and personal tensions caused Singapore to break away from Malaysia in 1965 and proclaim its independence. With the end of the Konfrontasi, the Royal Air Force withdrew its last V-bombers from the region in 1966. The following year the British government announced its intention to withdraw any remaining troops from the Far East. On December 8, 1968, the Singapore Naval Base was officially handed over to the Singapore government.

literature

- Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 2000, ISBN 0-8047-3978-1 , OCLC 45224321 .

- Christopher M. Bell: The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan. Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z. In: The English Historical Review. Volume 116, No. 467, June 2001, doi: 10.1093 / ehr / 116.467.604 , ISSN 0013-8266 , pp. 604-634.

- J. Bartlet Brebner: Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference. In: Political Science Quarterly. Volume 50, No. 1, March 1935, doi: 10.2307 / 2143412 , pp. 45-58.

- Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. In: Journal of Contemporary History. Volume 9, No. 2, April 1974, doi: 10.1177 / 002200947400900203 , pp. 69-92.

- James Lea Cate: The Pacific. Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945 . In: Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate (Eds.): The Twentieth Air Force and Matterhorn. (= The Army Air Forces in World War II. Volume V). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1953, OCLC 9828710 .

- Winston Churchill : The Hinge of Fate. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts 1950, ISBN 0-395-41058-4 , OCLC 396148 .

- David Day: The Great Betrayal. Britain, Australia and the Onset of the Pacific War, 1939-1942. Norton, New York 1988, ISBN 0-393-02685-X , OCLC 18948548 .

- Peter Dennis: Australia and the Singapore Strategy. In: Brian P. Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Eds.): A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore 2010, ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9 , OCLC 462535579 .

- Peter Edwards: A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965-1975. Allen and Unwin, 1997, ISBN 1-86448-282-6 .

- Brian P. Farrell: Introduction. In: Brian P. Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Eds.): A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore 2010, ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9 , OCLC 462535579 .

- John R. Ferris: Student and Master. The United Kingdom, Japan, Airpower and the Fall of Singapore. In: Brian P. Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Eds.): A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore 2010, ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9 , OCLC 462535579 .

- Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. (= Cass Series - Naval Policy and History. Volume XXII). Frank Cass, London 2004, ISBN 0-7146-5321-7 , ISSN 1366-9478 , OCLC 52688002 .

- G. Hermon Gill: Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942 ( Memento of September 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). (= Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Series 2, Volume I). Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1957, ISBN 0-00-217479-0 , OCLC 848228 .

- Douglas Gillison: Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942 . (= Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Row 3, Volume I). Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1962, OCLC 2000369 .

- Ken Hack and Kevin Blackburn: Did Singapore Have to Fall? Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 0-415-30803-8 , OCLC 310390398 .

- Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. In: The International History Review. Volume 25, No. 2, June 2003, doi: 10.1080 / 07075332.2003.9640998 , ISSN 0707-5332 , pp. 306-333.

- Greg Kennedy: Symbol of Imperial Defense. In: Brian P. Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Eds.): A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore 2010, ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9 , OCLC 462535579 .

- Gavin Long: To Benghazi . (= Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Row 1, Volume I). Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1952, OCLC 18400892 .

- Ian C. McGibbon: Blue-Water Rationale. The Naval Defense of New Zealand, 1914-1942. Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand 1981, ISBN 0-477-01072-5 , OCLC 8494032 .

- W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. (= Cambridge Commonwealth Series. ). MacMillan Press, London 1979, ISBN 0-333-24867-8 , OCLC 5860782 .

- Alan R. Millett: Assault from the Sea. The Development of Amphibious Warfare between the Wars. The American, British and Japanese Experiences. In: Williamson Murray , Alan R. Millett (Eds.): Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996, ISBN 0-521-55241-9 , OCLC 33334760 .

- Malcolm M. Murfett: An Enduring Theme. The Singapore Strategy. In: Brian P. Farrell and Sandy Hunter (Eds.): A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish Editions, Singapore 2010, ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9 , OCLC 462535579 .

- Rab Paterson: The Fall of Fortress Singapore. Churchill's Role and the Conflicting Interpretations. In: Sophia International Review. Volume 30, 2008, ISSN 0288-4607 , pp. 31-68. ( PDF file ).

- Stephen Wentworth Roskill: The Defensive. (= History of the Second World War - The War at Sea. Volume I). Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1954, OCLC 66711112 .

- Geoffrey Till: Adopting the Carriar Aircraft. The British, American and Japanese Case Studies. In: Williamson Murray and Alan R. Millett (Eds.): Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996, ISBN 0-521-55241-9 , OCLC 33334760 .

- Merze Tate and Fidele Foy: More Light on the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. In: Political Science Quarterly. Volume 74, No. 4, December 1959, doi: 10.2307 / 2146422 , pp. 532-554.

- Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust ( October 12, 2013 memento on the Internet Archive ). (= Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Row 1, Volume IV). Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1957, OCLC 3134219 .

- Humphrey Wynn: RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces. The Stationery Office, London 1994, ISBN 0-11-772833-0 , OCLC 31612798 .

Individual evidence

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 214.

- ^ A b c Winston Churchill: The Hinge of Fate. 1950, p. 81.

- ^ Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. 1974, p. 69.

- ^ The New York Times: Urges a Navy Second to None . December 22, 1915.

- ^ A b c d W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. 1979, pp. 19-23.

- ^ A b Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. 1974, p. 74.

- ^ Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. 1974, p. 70.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ Merze Tate and Fidele Foy: More Light on the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. 1959, p. 539.

- ^ J. Bartlet Brebner: Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference. 1935, p. 48.

- ^ J. Bartlet Brebner: Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference. 1935, p. 54.

- ↑ Merze Tate and Fidele Foy: More Light on the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. 1959, pp. 535-538.

- ↑ Merze Tate and Fidele Foy: More Light on the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. 1959, p. 543.

- ^ J. Bartlet Brebner: Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference. 1935, pp. 48-50.

- ^ J. Bartlet Brebner: Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference. 1935, p. 56.

- ^ A b W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. 1979, pp. 30-32.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, pp. 103-105.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, pp. 26-28.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, p. 60.

- ^ A b W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. 1979, pp. 4-5.

- ^ Peter Dennis: Australia and the Singapore Strategy. 2010, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ a b c Christopher M. Bell: The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan. Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z. 2001, pp. 608-612.

- ^ Rab Paterson: The Fall of Fortress Singapore. Churchill's Role and the Conflicting Interpretations. 2008, pp. 51-52.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, pp. 93-94.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 174.

- ^ A b Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. 2000, pp. 84-85.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, pp. 77-78.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Alan R. Millett: Assault from the Sea. The Development of Amphibious Warfare between the Wars. The American, British and Japanese Experiences. 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, pp. 159-164.

- ^ Alan R. Millett: Assault from the Sea. The Development of Amphibious Warfare between the Wars. The American, British and Japanese Experiences. 1996, pp. 61-63.

- ^ Pearson Phillips: The Highland peer who prepared Japan for war. In: The Daily Telegraph . January 6, 2002. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ John R. Ferris: Student and Master. The United Kingdom, Japan, Airpower and the Fall of Singapore. 2010, pp. 76-78.

- ^ John R. Ferris: Student and Master. The United Kingdom, Japan, Airpower and the Fall of Singapore. 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Geoffrey Till: Adopting the Carriar Aircraft. The British, American and Japanese Case Studies. 1996, pp. 218-219.

- ^ Geoffrey Till: Adopting the Carrier Aircraft. The British, American and Japanese Case Studies. 1996, p. 217.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, p. 153.

- ^ A b W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. 1979, pp. 156-161.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan. Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z. 2001, pp. 613-614.

- ^ Andrew Field: The Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939. Preparing for War against Japan. 2004, pp. 107-111.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 25-27.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 55.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 57-58.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 61-65 and 80.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 67.

- ^ Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. 1974, p. 80.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 71-73.

- ^ A b Charles H. Bogart: The Fate of Singapore's Guns - Japanese Report. ( Memento of the original from 23 August 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Naval Historical Society of Australia. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 120-122.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 74.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 75-81.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 83.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 135-137.

- ↑ a b c Gavin Long: To Benghazi. 1952, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Gavin Long: To Benghazi. 1952, p. 10.

- ^ Peter Dennis: Australia and the Singapore Strategy. 2010, p. 22.

- ↑ G. Hermon Gill: Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942. 1957, pp. 18-19.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, p. 8.

- ^ Peter Dennis: Australia and the Singapore Strategy. 2010, pp. 23-25.

- ^ A b Gavin Long: To Benghazi. 1952, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Gavin Long: To Benghazi. 1952, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Gavin Long: To Benghazi. 1952, p. 27.

- ↑ David Day: The Great Betrayal. Britain, Australia and the Onset of the Pacific War, 1939-1942. 1988, pp. 23-31.

- ↑ a b c Rab Paterson: The Fall of Fortress Singapore. Churchill's Role and the Conflicting Interpretations. 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ David Day: The Great Betrayal. Britain, Australia and the Onset of the Pacific War, 1939-1942. 1988, p. 31.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 165.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, p. 19.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 156.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 163.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 178-179.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 182.

- ↑ a b Stephen Wentworth Roskill: The Defensive. 1954, pp. 553-559.

- ^ Christopher M. Bell: The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan. Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z. 2001, pp. 620-623.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, p. 92.

- ^ Raymond Callahan: The Illusion of Security. Singapore 1919-42. 1974, p. 83.

- ^ Douglas Gillison: Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942. 1962, pp. 142-143.

- ^ Douglas Gillison: Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942. 1962, pp. 204-205.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Ken Hack and Kevin Blackburn: Did Singapore Have to Fall? Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. 2003, pp. 90-91.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 192-193.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, p. 144.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, pp. 382 and 507.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, p. 208.

- ^ Lionel Wigmore: The Japanese Thrust. 1957, pp. 182-183, 189-190 and 382.

- ^ A b c W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. 1979, p. 230.

- ↑ a b Christopher M. Bell: The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan. Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z. 2001, pp. 605-606.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 214-216.

- ^ Brian P. Farrell: Introduction. 2010, p. Ix.

- ↑ Malcolm M. Murfett: An Enduring Theme. The Singapore Strategy. 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Commonwealth of Australia: Parliamentary Debates. House of Representatives, February 27, 1992.

- ^ W. David McIntyre: The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919-1942. 1979, pp. 221-222.

- ^ Greg Kennedy: Symbol of Imperial Defense. 2010, p. 52.

- ↑ James Lea Cate: The Pacific. Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945. 1953, p. 156.

- ^ Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. 2003, pp. 316-318.

- ^ Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. 2003, pp. 320-322.

- ^ Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. 2003, p. 325.

- ^ Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. 2003, p. 329.

- ^ Matthew Jones: Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962. 2003, p. 333.

- ^ Humphrey Wynn: RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces. 1994, pp. 444-448.

- ↑ a b Humphrey Wynn: RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces. 1994, p. 448.

- ^ Peter Edwards: A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965-1975. 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Peter Edwards: A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965-1975. 1994, p. 146.