Soviet intervention in Afghanistan

| date | December 25, 1979 to February 15, 1989 |

|---|---|

| place | Afghanistan |

| output | Withdrawal of the Soviet troops and takeover of the opposing parties to the conflict |

| consequences | Civil War in Afghanistan (1989-2001) |

| Peace treaty | Geneva Convention of April 14, 1988 |

The Soviet intervention in Afghanistan ( Pashtun په افغانستان کې شوروی جګړه, Persian جنگ شوروی در افغانستان, DMG Ğang-i Šouravī dar Afġānistān , 'War of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan'; Russian Афганская война Afganskaja wojna , German 'Afghan War' ) took place between 1979 and 1989. It began with the military support by the Soviet Union of the Afghan rulers who had come to power after a coup against the numerous groups of the Mujahedin , which formed primarily as a reaction to the secularization of Afghanistan. These Islamist rebel groups were subsequently supported politically and materially by the USA and some NATO countries and parts of the Islamic world . With the invasion and assassination of Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin , the government of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) was supposed to be "stabilized". In addition, it was supposed to stop further meetings with US diplomats and prevent an Islamic revolution along the lines of Iran .

course

Afghan Civil War until 1979

After the coup d'état by the Communist Democratic People's Party of Afghanistan (DVPA) under Nur Muhammad Taraki on April 27, 1978 through the acid revolution , the latter operated a rapprochement with the Eastern bloc in order to promote social transformation (expropriations for land reform).

In particular, the forced secularization as well as the disempowerment and sometimes murder of the upper class quickly led to broad resistance from the population. Around 30 Islamist mujahideen groups were founded during this time. In addition, there were political disputes over direction and power struggles within the DVPA. With the assassination of Prime Minister Nur Muhammad Taraki in September 1979, Hafizullah Amin took power and tried to put down the resistance. As a result, the civil war escalated, which was soon supported and financed by the CIA .

Since the end of 1978, Taraki had repeatedly and urgently asked for Soviet military aid to fight civil unrest. At that time, the Soviet Union rejected military aid, partly because of the high foreign policy risk. However, since the KGB feared that Amin could lean on the West and call NATO troops into the country to secure his power, voices in the leadership of the USSR increased in favor of a temporary military intervention. When relations with the West had reached a new low after the NATO double decision of December 12, 1979, this position prevailed, and so Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev gave the order for action. However, this was not an expression of the Brezhnev doctrine , with which the Soviet Union granted itself the right to intervene in socialist states. Afghanistan under the Taraki regime was not regarded as a socialist state, but only as a “state of socialist orientation”.

The reason given for the intervention was concern for the Muslim population of the southern Soviet republics, who could possibly be infected by the uprising of the Afghan resistance groups. It is also believed that the Soviet Union was pursuing the strategic goal of penetrating as far as the Indian Ocean. The German political scientist Helmut Hubel, on the other hand, advocates the thesis that the Soviet leadership, from a position of its own strength, would have wanted to defend its position of power, which was already believed to be secure, and to keep Afghanistan in its sphere of influence .

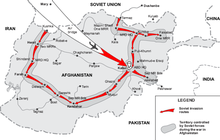

Soviet invasion

On December 25, 1979, the first units of the newly formed Soviet 40th Army under Marshal Sergei Sokolow , the 5th and 108th Motorized Rifle Divisions, crossed the border into Afghanistan at Termiz and Kuschka . At the same time, 7,000 elite soldiers from the 103rd Vitebsk Airborne Division were flown into Kabul and Bagram . On the first day of the invasion, the pilot, 37 paratroopers and nine other soldiers were killed in a crash of an Il-76 military transport aircraft on a mountain near Kanzak (northeast of Kabul).

On December 27, special forces of the KGB , which had been in the country for some time, carried out Operation Storm-333 with the support of paratroopers , by storming the Tajbeg Palace and other operationally important points in Kabul and killing Amin. The previous Afghan leadership was eliminated in one fell swoop, political prisoners were freed and on the same day the takeover of government by Babrak Karmal was announced on the radio . Resistance from the Afghan army was low and most of the commanders soon agreed to cooperate with the new government under the influence of the Soviet military advisers who were on their side . This tried on the one hand to de-escalate the civil war and on the other hand to strengthen the ties to the Soviet Union, among other things through an agreement on the stationing of troops.

The limited contingent of Soviet troops in Afghanistan (official name; Russian Ограниченный контингент советских войск в Афганистане, OКСВА) already comprised 85,000 soldiers in February 1980. The troop strength was increased further to about 115,000 by 1988.

International response

The military intervention was immediately condemned by Western and Islamic states. It overshadowed the 1980 Summer Olympics (Moscow / Tallinn) , which were therefore boycotted by many countries.

Military resistance

About two thirds of the Afghan army joined the resistance against the Soviets. The conservative mujahideen received increasing international support. On March 21, 1980, the Islamic Alliance for the Freedom of Afghanistan was founded as an alliance of Islamist and monarchist groups. These were divided among themselves and the cooperation was limited to the fight against communist rule. The war was ruthless and cruel on both sides; both the Soviets and government forces and the mujahideen committed war crimes.

The fight against the Soviet invaders and the communist government was led in particular by an alliance of seven Islamic parties , which had their joint general staff in Pakistan and were at odds with one another. The leaders of these parties were also called warlords (" warlords ") by the western press . Pakistan, which particularly supported the Islamist warlord Hekmatyar intensively and pursued its own interests in the neighboring country, was the most important ally of the anti-communist forces alongside the USA.

Despite their military superiority and air sovereignty, the Soviet and Afghan government troops did not succeed in breaking the resistance of the mujahideen. While they could quickly occupy important cities and roads in the valleys, they had no control over large areas outside the big cities. A military stalemate was finally reached in 1982, as the struggle became increasingly brutal on both sides. The Soviet army reacted to the guerrilla tactics of the mujahideen in hunting , which usually did not take prisoners, with terrorism against the civilian population. A turning point in the ongoing conflict came in 1986 with the election of Mikhail Gorbachev as the new general secretary of the CPSU , who had started with the promise to end the war in Afghanistan. This at a time when the Soviets had begun to move their troops by transport helicopters and Mil Mi-24s transporting troops to combat areas in the country in order not to have to fight the rebels from below. After the first such successes, as a result of the CIA's delivery of state -of-the- art Stinger missiles to the mujahideen , the Soviet troops lost the possibility of such air transport . The Soviet leadership realized that the war was not to be won and henceforth looked for a way to withdraw their troops from the country without losing face.

In May 1986, Mohammed Najibullah succeeded Karmal as head of government and tried to defuse the war through negotiations. Babrak Karmal remained chairman of the Revolutionary Council and thus head of state until November 20, 1986.

Withdrawal of the Soviet troops

The indirect negotiations between Afghanistan and Pakistan, which began in 1982 in Geneva with the mediation of the United Nations, led to the signing of the Geneva Agreement on April 14, 1988 , which provided for the normalization of relations between the two countries and non-interference in the internal affairs of the other country. In addition, the return of the Afghan refugees in Pakistan was agreed. The Soviet Union and the United States guaranteed the renunciation of any interference in the internal affairs of Afghanistan. The withdrawal of the Soviet troops was to be completed by mid-February 1989. The mujahideen rejected the agreement that came into force on May 15, 1988, and did not want to participate in the coalition government under Najibullah. From May 15, 1988, the Soviet Union began to withdraw officially 100,300 soldiers from Afghanistan. According to journalist Sawik Schuster , Gorbachev had insisted on a UN guarantee that no Mujadehin soldiers would be killed while the troops were withdrawn. On a secret UN mission, Schuster was in Afghanistan in April 1988 and received the promise Gorbachev demanded from the combined commanders a week before the Geneva Agreement was signed. Due to further attacks by the mujahideen, however, the Soviet soldiers were again involved in fighting in July 1988, a description which Schuster strongly contradicted; "Never" would any shots have been fired from the guards that the Mujadehin had set up along the road from Kabul to Termiz . On the contrary, the Soviets broke their promise when up to two thousand civilians were killed in Operation Typhoon from January 23, 1989. Dead civilians had been filed as charges on the street where the troop withdrawal took place.

The withdrawal was over by February 15, 1989. Afghanistan had over a million deaths and five million people had fled the country because of the war. On the Soviet side, around 13,000 soldiers died in the more than nine years of war .; According to later information from the Russian General Staff, there were over 26,000 deaths on the Soviet side.

The way to the new civil war

The withdrawal of Soviet troops left Afghanistan politically and militarily disordered. Like the heterogeneous resistance, the Mohammed Najibullah government was unable to develop its claim to leadership and form a government that was largely accepted by the population. As early as January 1989, Kabul, which was enclosed by the Mujahideen, was only supplied via a Soviet airlift . The anti-communist resistance organizations formed a counter-government in Peshawar, Pakistan in February 1989 . After the last Soviet soldier withdrew on February 15, 1989, the Soviet Union initially provided material support for the leadership in Kabul. Since the Geneva Agreement only regulated the withdrawal of the armed forces, numerous Soviet advisors remained in Kabul. The battle of Jalalabad raged until the summer , in which the groups of the Mujahedin were unsuccessful. The mujahideen, especially their largest parties Hizb-i Islāmī and Jamiat-i Eslami-ye Afghanistan under Burhānuddin Rabbāni , became entangled in fights that lasted for years. In the spring of 1990, then Minister of War Nawaz Tanai attempted a coup against Najibullah. This failed and political cleansing followed. Nevertheless, as a result of the increasing resistance, the communist ruling party gave up its monopoly of power in June 1990 and renamed itself the “Home Party” (“ Watan ”).

By the spring of 1992, the Mujahideen had brought most of Afghanistan under their military control. On April 16, 1992, Najibullah relinquished power through the mediation of the UN after Russia, the successor state of the USSR, agreed with the United States to stop the respective military aid and agreed to accept an Islamic government in Afghanistan. A council of four from Najibullah's Watan party took over the political leadership. On April 25, 1992, Kabul was surrendered to the Mujahedin without a fight and divided into six spheres of influence, the borders of which were mined. In the days that followed, the mujahideen took over all the other towns and garrisons in the area. However, the various mujahideen groups began to fight each other immediately after the capture of Kabul. Another civil war broke out .

The fundamentalist Taliban finally emerged victorious from the subsequent clashes, which met with little interest in the West, and established an Islamist state of God .

Role of individual states

Pakistan

At the time of the entry of the Soviet troops, Pakistan was under an Islamist military government under Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq . Pakistan felt its existence threatened by the Soviet Union advancing into Afghanistan in the west and the Soviet ally India in the east and wanted to prevent a possible coordinated attack by the two hegemonic powers. Both the defense of Islam and the Pakistani state played a role. Zia entrusted General Akhtar Abdur Rahman Shaheed , General Director of the Secret Service, who is considered the country's second greatest authority , with working out possible solutions, and finally decided to secretly support the mujahideen. Zia hoped for support from the Arab world as a fighter for Islam and from the West as an opponent of communism.

Even before the war began, Afghan Islamist parties, which were in conflict with the secular Afghan government under Mohammed Daoud Khan , settled in Peshawar, Pakistan. With the Soviet invasion, Pakistan stepped up its efforts to support the Sunni resistance. Seven mujahideen groups selected by Pakistan were allowed to settle in Pakistan. The Pakistani secret service Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) took over the organization and training of the various mujahideen groups, the distribution of weapons and other resources as an intermediary, and the strategic planning of the war. Pakistan used the “strategy of a thousand pinpricks”, which consisted of destabilizing the enemy through a large number of guerrilla attacks. Pakistan's role in the war in Afghanistan has always been denied from the official side.

The ISI base from which the Afghanistan war was directed was the Ojhri camp in the north of Rawalpindi . In addition to a camp through which 70% of the weapons passed, there was also a training camp with simulators, which was later used in particular for the Stinger missiles , and a unit for psychological warfare . Other ISI camps were located near the mujahideen quarters in Peshawar and Quetta . From 1984 to 1987, over 80,000 mujahideen underwent weapons training in Pakistani camps.

United States

The National Security Advisor to US President Jimmy Carter , Zbigniew Brzeziński , claims that Carter, with the support of the mujahedin he recommended, increased the likelihood that the Soviet Union would fall into what he later called the “Afghan trap”. The claim that the Soviets were lured into such a trap is rejected by contemporary witnesses as "not based on facts".

In the first months of the war, the United States Department of Defense and the CIA were reluctant to support Zia, as the Soviet Union's early control of Afghanistan seemed inevitable. In fact, after the capture of Kabul, the new regime was recognized by the USA by sending the ambassador Adolph Dubs to the Afghan capital as diplomatic representative.

However, leading members of the CIA, including its director William Joseph Casey , soon saw war not just as a way of fighting communism in general. The opportunity arose to make people forget the lost Vietnam War in Afghanistan . The role of the CIA was both to provide weapons and to assist Pakistan with intelligence such as satellite images and tapped radio messages from the Soviet Army. The weapons came from China , Egypt , Israel , the USA , Great Britain and other countries. They were delivered to Pakistan by the CIA, from where the ISI distributed them to the bases of the mujahideen leaders. The total financial volume of US support ranged between two and six billion US dollars.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has supported the Sunni mujahideen since 1980 . The country doubled funding for the mujahideen from the United States. In addition, Saudi Arabia financed the participation in the war of Islamist extremists who were in opposition to the Saudi royal family.

Iran

Iran took in around 1.7 to 2.2 million Afghan refugees. The country supported the Shiite mujahideen. Since Iran was in the First Gulf War during the Soviet-Afghan War , support from Iran remained low. At the urging of Iran, the Shiite mujahideen parties united in 1989.

Federal Republic of Germany

The invasion of the Red Army was the beginning of the German Operation Summer Rains of the Federal Intelligence Service . The aim was to get the most modern military equipment from the Soviet Union to West Germany. The Federal Republic of Germany is also said to have supported the mujahideen.

German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic trained soldiers, NCOs and officers of the Afghan armed forces, and police officers were trained. The NVA supported the Afghan army with communications technology. There was also cooperation between the Stasi and the Afghan secret service. The Stasi is said to have trained around 1,000 Afghans. The main part of GDR-Afghan cooperation in the GDR, however, lay in support for the education sector.

Other states

Numerous other states are associated with the support of the Mujahideen, such as the People's Republic of China , the United Kingdom , Egypt , Turkey , Israel , Japan , Libya or France . However, the nature and extent of support from these states have so far hardly been researched.

Perception in western states

Due to the difficult conditions of the extremely tough guerrilla struggle, few journalists were able to accompany the mujahideen, and the information published about this war necessarily remained inaccurate and influenced. Some journalists persuaded the mujahideen commanders to simulate missile attacks on camera. Much of the film footage of the war was made by private individuals who used this material to solicit financial support for the mujahideen in western countries. Another large part of the privately produced film recordings dealt with the situation of the refugees who were dependent on outside help in the Pakistani and Iranian refugee camps.

Consequences for the Soviet Union

The Afghan War was extremely unpopular in the Soviet Union itself. Many young conscripts from all over the Soviet Union who had to fight as soldiers in this war fell ill, suffered injuries and / or war trauma or died. In addition, the Afghan war acted as a catalyst for the growing drug problem and crime within the Soviet Union, because it promoted the spread of narcotic drugs such as heroin enormously. In this respect, too, there is a parallel to the US war in Vietnam . Because of the secrecy surrounding all military affairs and the censorship of the media, reports on these aspects of the war were impossible. The Soviet population could not identify with the goals of the mission "in the foreign desert"; the confidence of the Soviet people in the political leadership continued to decline. The Afghan war and its enormous costs hastened the process that eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union . Assaults by the mujahideen on Soviet territory remained the exception.

Reception in the cinema

In the late 1980s the issue was in several Hollywood - action films processed. The international rejection of the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan was used to upgrade the respective film hero, who fought on the side of the locals against the Soviet invaders, as in James Bond 007 - The Living Daylights , Rambo III , Bestie Krieg or Red Scorpion . The 1994 film Ken Follett's Red Eagle , based on Ken Follett's thriller The Lions , also uses the events in Afghanistan as a framework. The political background to the financing of the insurgents by the CIA is dealt with in the 2007 film Charlie Wilson's War . Adam Curtis' 2015 documentary Bitter Lake is also dedicated to this complex of issues.

The subject was also taken up in films in the Soviet Union and Russia, such as in Hot Summer in Kabul from 1983, in Afghan Breakdown from 1990 or in The Ninth Company from 2005, where combat operations by the Soviet Army against the mujahideen in 1988 be thematized.

See also

literature

- Svetlana Alexijewitsch : zinc boys, Afghanistan and the consequences . 1st edition 2016, Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-3-518-46648-3 .

- Pierre Allan, Dieter Klay: Between Bureaucracy and Ideology: Decision-making Processes in Moscow's Afghanistan Conflict , 1st edition, Haupt Verlag, Bern Stuttgart Vienna 1999.

- Douglas A. Borer: Superpowers defeated Vietnam and Afghanistan compared , 1st edition 1999, Frank Cass Publishers, London 1999.

- Gennady Botscharow: The shock. Afghanistan - Soviet Vietnam. Structure of the Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-7466-0070-7 .

- Rodric Braithwaite: Afghantsy. The Russians in Afghanistan 1979–1989 , Profile Books, London 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-983265-1 .

- Bernhard Chiari: The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the occupation from 1979 to 1989 in: Bernhard Chiari (Hrsg.): Afghanistan. Guide to history , published by the Military History Research Office , Paderborn, ISBN 978-3-506-76761-5 .

- Steve Coll : Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Books, London 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-193579-9 .

- Konstanze Fröhlich: Afghanistan hotspot an analysis of the regional security effects, 1979–2004 , 1st edition, Arnold-Bergstraesser-Inst., Freiburg im Breisgau 2005.

- David N. Gibbs: The Background of the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 . In: Bernd Greiner, Christian Th. Müller, Dierk Walter (eds.): Hot wars in the cold war . Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-936096-61-9 , pp. 291-314. ( Review by H. Hoff , review by I. Küpeli ).

- Antonio Giustozzi: War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan 1978–1992 . Georgetown University Press 2000, ISBN 0-87840-758-8 .

- Jan-Heeren Grevenmeyer: Afghanistan after over ten years of war. Perspectives of social change , Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-88402-018-8 .

- David C. Isby: War in a Distant Country - Afghanistan: Invasion and Resistance . Arms and Armor Press, 1986, ISBN 0-85368-769-2 .

- M. Hassan Kakar: Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982 . University of California Press, Berkeley 1995.

- Robert D. Kaplan : Soldiers of God: With Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan . Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990, ISBN 1-4000-3025-0 .

- William Maley: The Afghanistan Wars , 1st edition, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire 2002.

- Thomas J. Moser: Politics on the path of God, On the genesis and transformation of militant Sunni Islamism , IUP, Innsbruck 2012, pp. 105–120, ISBN 978-3-902811-67-7 .

- Tanja Penter, Esther Meier (Ed.): Sovietnam. The USSR in Afghanistan 1979–1989 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-506-77885-7 .

- Michael Pohly: War and Resistance in Afghanistan: Causes, Course and Consequences since 1978 , 1st edition, Das Arabische Buch, Berlin 1992.

- Oliver Roy: Islam and Resistance in Afghanistan , Cambridge 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-39700-1 .

- Mark Urban: Was in Afghanistan . Macmillan Press 1988, ISBN 0-333-51478-5 .

- The Russian General Staff: The Soviet-Afghan War. How a Superpower Fought and Lost . Translated and edited by Lester W. Grau and Michael A. Gress, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 2002, ISBN 0-7006-1185-1 , ( online ).

- Mohammad Yousaf, Mark Adkin: Afghanistan - The Bear Trap: The Defeat of a Superpower . Casemate, 2001, ISBN 0-9711709-2-4 , (German translation: The bear trap. The fight of the mujahideen against the Red Army - ISBN 3-924753-50-4 or ISBN 3-89555-482-0 ).

- Odd Arne Westad: The Global Cold War - Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times . Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-70314-7 .

- Artemy M. Kalinovsky: A Long Goodbye - The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan . Harvard University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8 .

Web links

- Islamism and Great Power Politics in Afghanistan

- Henning Sietz: The war that couldn't be won ( Die Zeit article, 40/2001)

- Interview with ex-President Carter's security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski

- Russia in Afghanistan 1979 to 1989 - video in three parts

- Nicolas Jallot: Nightmare Afghanistan - Death Struggle of the Soviet Union. ZDFinfo, 2019 .

- Mayte Carrasco, Marcel Mettelsiefen: Afghanistan. The wounded land. Arte, 2020 .

Individual evidence

- ^ India to Provide Aid to Government in Afghanistan - NYTimes.com, March 7, 1989

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Cold War, Volume 2 in Google Book Search

- ↑ Lally Weymouth: EAST GERMANY'S DIRTY SECRET . In: Washington Post . October 14, 1990.

- ^ German-Afghan and GDR-Afghan relations

- ^ The Pakistan Taliban - Geopolitical Monitor

- ↑ CRG - Who Is Osama Bin Laden? ( Memento from May 25, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) - South Asia Analysis Group ( Memento from September 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ stj: "Operation Summer Rain": BND agents were active in the Afghan war against the Soviets. In: Focus Online . October 6, 2013, accessed October 14, 2018 .

- ↑ http://www.mepc.org/articles-commentary/commentary/lessons-soviet-withdrawal-afghanistan

- ^ A b Richard F. Nyrop, Donald M. Seekins: Afghanistan: A Country Study . United States Government Printing Office , Washington, DC January 1986, p. XVIII-XXV . here ( Memento from November 3, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20111121131224/http://www.global-politics.co.uk/issue6/Stahl/

- ^ The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan - Total War Center Forums

- ^ Afghanistan hits Soviet milestone - Army News

- ^ Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century

- ^ Hilali, A. (2005). US-Pakistan relationship: Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co. (p. 198).

- ↑ Florian Rötzer: Ongoing war in Afghanistan causes severe environmental damage. In: Telepolis , 23 August 2007.

- ↑ Files show Western aid for Islamists in Afghanistan. In: Die Zeit , December 30, 2010.

- ^ Joseph J. Collins: Understanding War in Afghanistan . National Defense University Press, Washington, DC 2011. ISBN 978-1-78039-924-9 .

- ↑ 'Timeline: Soviet Was in Afghanistan' , BBC News, February 17, 2009, accessed December 15, 2018.

- ↑ Kate Clark: Afghan Death List Published: Families of forcibly disappeared end 30 yr wait. Afghanistan Analysts Network, September 26, 2013, accessed October 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Helmut Hubel: The end of the Cold War in the Orient. The USA, the Soviet Union and the conflicts in Afghanistan, the Gulf and the Middle East 1979–1991 . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1994 ISBN 978-3-486-82924-2 , pp. 132-136; similar to Bernhard Chiari: Kabul, 1979. Military Intervention and the Failure of Soviet Third World Policy in Afghanistan. In: Andreas Hilger (Ed.): The Soviet Union and the Third World. USSR, State Socialism and Anti-Colonialism in the Cold War 1945–1991 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-70276-7 , pp. 259–280, here p. 267 (both accessed via De Gruyter Online): “Overall, the Soviet policy on Afghanistan up to the crisis of 1978/79 appears to be long-term systematic plan designed to integrate the country into the Soviet sphere of power ”.

- ↑ Aviation Safety Network ( Memento from September 22, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Wichard Woyke: Formative conflicts after the Second World War . In: Wichard Woyke: Concise dictionary of international politics . 9th edition, Wiesbaden 2004, p. 419.

- ^ Conrad Schetter: Brief history of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. Beck, 2010, p. 102 .

- ↑ Amnesty International: Country Report of January 11, 2001 ( Memento of October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d Every input has an output. , Novaya Gazeta, January 6, 2020

- ↑ Knaurs Weltspiegel 1989 . ISBN 3-426-07797-3 .

- ↑ Major General Alexander Antonowitsch Lyakhovsky: "If you order that I shoot, I will obey the order, but I will curse myself." , February 13, 2009

- ↑ 'Timeline: Soviet Was in Afghanistan' , BBC News, February 17, 2009, accessed December 15, 2018

- ↑ The Russian General Staff: The Soviet-Afghan War. How a Superpower Fought and Lost . Translated and edited by Lester W. Grau and Michael A. Gress, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 2002, ISBN 0-7006-1185-1 , pp. 43-44 ( online ).

- ↑ Olaf Kellerhoff: The role of the military in the political system of Pakistan. In: bpb.de. May 14, 2010, accessed April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Conrad Schetter: Brief history of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. Beck, 2010, p. 108 .

- ↑ Conrad Schetter: Ethnicity and ethnic conflicts in Afghanistan . S. 425 .

- ↑ Michel Chossudovsky: The staged terrorism: The CIA and Al Qaeda. In: globalresearch.ca. Retrieved August 9, 2016 . (Quoted from the Canadian globalization critic Michel Chossudovsky )

- ^ Bob Gates: From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider's Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War . Simon and Schuster, 2007, ISBN 9781416543367 , pp. 145-47. When asked whether he expected that the revelations in his memoir (combined with an apocryphal quote attributed to Brzezinski) would inspire "a mind-bending number of conspiracy theories which adamantly — and wrongly — accuse the Carter Administration of luring the Soviets into Afghanistan," Gates replied: "No, because there was no basis in fact for an allegation the administration tried to draw the Soviets into Afghanistan militarily." See Gates, email communication with John Bernell White, Jr., October 15, 2011, as cited in John Bernell White: The Strategic Mind Of Zbigniew Brzezinski: How A Native Pole Used Afghanistan To Protect His Homeland . May 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved on April 20, 2019.

- ↑ In December 2018, the US State Department published a comprehensive review of US policy: https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/12/288220.htm

- ↑ Conrad Schetter : Ethnicity and ethnic conflicts in Afghanistan . Ed .: Dietrich Reimer Verlag . S. 424 .

- ↑ Hasnain Kazim : The Soviet Waterloo. In: Spiegel Online . December 22, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2016 .

- ^ Guido Steinberg: Saudi Arabia. Politics, history, religion . ISBN 978-3-406-65017-8 , pp. 66 .

- ↑ Schetter, Conrad: Small history of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. 2010, p. 104 f .

- ^ Conrad Schetter: Brief history of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. Beck, 2010, p. 109 .

- ↑ Andreas Rieck: Iran's Politics in the Afghanistan Conflict since 1992 . In: Conrad Schetter; Almut Wieland-Karimi (ed.): Afghanistan in past and present. Contributions to Afghanistan research . 1999, p. 109 .

- ^ Conrad Schetter: Brief history of Afghanistan . 2nd Edition. 2010, p. 116 f .

- ↑ a b c Michael Pohly: War and Resistance in Afghanistan . S. 154 .

- ↑ Lally Weymouth: EAST GERMANY'S DIRTY SECRET . In: Washington Post . October 14, 1990.

- ^ German-Afghan and GDR-Afghan relations

- ↑ a b Bernd Stöver: The Cold War. Story of a radical age . S. 415 .

- ^ Inken Wiese: The engagement of the Arab states in Afghanistan. Retrieved March 18, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Conrad Schetter: Ethnicity and ethnic conflicts in Afghanistan . S. 430 .

- ^ William Maley: The Afghanistan Wars . 1st edition, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire 2002, pp. 159-162.