Thylacine

| Thylacine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bag wolves at the National Zoo in Washington, DC (circa 1904) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Thylacine | ||||||||||||

| Harris , 1808 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||||

| Thylacinus cynocephalus | ||||||||||||

| Harris, 1808 |

The thylacine ( Thylacinus cynocephalus ), and Tasmanian wolf , bags Tiger or Tasmanian tiger called, was the largest predator living marsupial that after the Quaternary extinctions on the Australian continent lived. The last known specimen (" Endling ") died in 1936 in the Hobart Zoo in Tasmania .

description

General

Pouch wolves reached a head body length of 85 to 130 centimeters, a tail length of 38 to 65 centimeters and a shoulder height of around 60 centimeters. The weight varied from 15 to 30 kilograms, with females with an average of 13.7 kilograms being significantly lighter than males with an average of 19.7 kilograms. Their fur was short and rough, colored gray or yellowish gray. The 13 to 19 black-brown horizontal stripes on the back of the body and on the base of the tail, from which it owes its name "marsupial tiger" and which served as camouflage, were striking. He had white markings around the eyes and ears on his face. In terms of physique, the thylacine wolf showed astonishing similarities with some predators from the family of dogs (Canidae) and thus represents a prime example of convergent evolution . The skull was built a little wider, the tooth formula was 4 / 3-1 / 1-3 / 3 -4/4 x2, so a total of 46 teeth (tooth formula of dogs: 3 / 3-1 / 1-4 / 4-2 / 3 x2 = 42). Similar to dogs, the canines were long and the molars were sharp. It is noteworthy that the animals were able to open their lower jaws very wide, according to some statements up to 90 degrees. The limbs were rather short, the legs each ended in five toes. The animals were toe walkers and probably reached a speed of up to 40 km / h.

Convergences

There are similarities between wolf and thylacine not only in name . Although the ancestors of the two animals shared ancestral history very early in the Cretaceous period , the group of marsupials and higher mammals each developed a predator with astonishing similarities. In general, the similarities in training and proportions clearly outweigh the comparison, so that in this case one can speak of a prime example of convergence . Both have predatory teeth with very small incisors and large, curved canines. The premolar teeth are single-humped and the molars have multiple cusps. The tooth formulas are:

- for the bag wolf: 4 1 3 4/3 1 3 4 = 46

- for the wolf: 3 1 4 2/3 1 4 2 = 40.

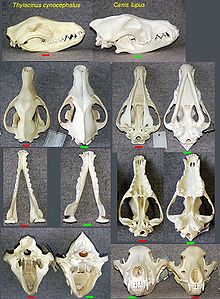

If you compare the skulls of these animals, not only inexperienced people find it very difficult to distinguish. The illustration on the right shows the skulls of the Tasmanian Wolf (red marking) and wolf (green marking) in different views. The clearest differences compared to the wolf are:

- In the side view: the base of the skull bends more strongly towards the bridge of the nose in profile; the forehead area is more voluminous; the zygomatic arch extends further back and widens there; the lower jaw is somewhat narrower.

- When viewed from above: the front skull in particular is narrower; The bulging forehead area is more clearly recognizable; the occiput appears truncated in comparison. The wolf's brain skull is proportionally much larger than that of the thylacine.

- When looking at the underside of the skull: in the area of the posterior margin of the palate there are two openings, the so-called palatal windows (characteristic of original mammals); The very small auditory bladders are noticeable at the rear edge of the zygomatic arches .

- When looking at the occiput at an angle from behind: the angular processes on the lower jaw are bent inwards, as in almost all marsupials.

distribution and habitat

At the time the Europeans arrived in Australia, the thylacine probably only lived in Tasmania . On the Australian mainland and New Guinea he had already disappeared. Its original habitat were open forest areas and grasslands, but in the last decades of its existence it was pushed into dense forests by humans.

Way of life

Tasmanian wolves were usually nocturnal, but could be seen sunbathing. There are different reports about the hunting technique. According to some reports, he chased his prey until it was tired and he could overwhelm them, according to other reports, he sneaked up on his victims and took them off guard. His strong jaw helped him do this - one report said he crushed a dog's skull with a single bite. However, recent research by a team led by Marie Attard from the University of New South Wales in Sydney using computer models and comparing teeth with other predators refutes this and confirms that the thylacine has rather low bite forces. According to the analyzes, the pouch- wolf appears to have mainly killed smaller animals such as wallabies and pouches . As a result, even sheep were too big as prey, and the extermination campaign against the thylacine as an alleged sheep killer was unjustified according to today's facts. In any case, he was not too fast, but an enduring runner. Sometimes it stood up like a kangaroo on its hind legs, with the tail serving as a support. He lived mostly alone, but sometimes he hunted in pairs or small groups. Well-known sounds included a dull bark during the hunt, a growl when he was annoyed, and a howl, which was presumably used to communicate with fellow dogs.

In general, Tasmanian wolves were described as rather shy and, compared to the Tasmanian devil, as less aggressive animals. There are very few reports of attacks on people, and animals in captivity are said to have behaved very tame .

food

It is believed that pouch wolves lived mainly on mammals such as Australian nosebabs , possums , wallabies and other small kangaroos , but also consumed other mammals (including wild rabbits and possibly also echins ) and birds . The extent to which it hunted sheep and other grazing animals after the arrival of the Europeans is controversial, as many of the sheep's cracks attributed to the thylacine were actually caused by feral dogs. In addition, researchers from the University of New South Wales , who ran a simulation with a 3D model of the thyroid's jaw, believe it was too weak to kill sheep.

Reproduction

Female marsupial wolves had a back open pouch that contained four teats. Most of the young animals were born during the summer of the southern hemisphere (December to March), the litter size was two to four young. After three months, the young left the pouch, but stayed with the mother until they were barely a year old. Life expectancy is estimated at a maximum of twelve to fourteen years.

Thylacine and human

Time before the Europeans

When the first humans settled the Australian continent, pouch wolves were widespread in large parts of Australia and New Guinea , as evidenced by Aboriginal rock carvings . For unknown reasons, however, pouch wolves became extinct in New Guinea and mainland Australia; the most recent fossil finds from the mainland (from the Northern Territory ) date back to 3000 BC. It is often assumed that the dingo , which was introduced by Austronesians to Australia 5,000 years ago , replaced the thylacine by increasing competitive pressure. This thesis is supported by the fact that the thylacine survived in Tasmania, where dingoes never appeared, until the 20th century.

Another theory takes into account that the extinction was caused by an increase in the human population. There is evidence of dramatic changes in the human population in many areas of Australia, which never reached Tasmania. These changes included a variety of innovations in hunting tools, population growth and settling in several areas, an intensification of the use of resources and the settlement of new areas into the deserts. Finds show that around 3000 years ago practically all of the main areas of the Australian continent were used by humans. On the one hand, the extinction could have been caused by direct hunting pressure (rock drawings from Northern Australia show how pouch wolves were carried away as prey). This approach is supported by grave finds with jewelry made from thylacine teeth, as well as the fact that Tasmania's aborigines hunted and ate thylacine wolves. On the other hand, there could have been a reduction in many types of prey and thus the displacement of the thylacine. An example is given with the grouse : Since the range of the grouse may have shrunk considerably before the dingo's arrival on the Australian continent, the intensification of hunting could also have led to the extinction of the thylacine. Consequently, this could explain why the Tasmanian devil was able to survive so much longer than the thylacine on the mainland, since the Tasmanian devil would have needed less large prey due to its smaller size and therefore would have been much less susceptible to the increased competitive pressure.

The intensification, the arrival of the dingo and the extinction of the thylacine also coincide with a climate change towards a briefly drier climate. Climate change is not seen as the main cause of the extinction, as the drought was relatively mild and also affected Tasmania. But it is also possible that this change accelerated the effects of intensification and the dingo. It is also likely that the effects of intensification and the dingo were linked, and the dingo was one of the reasons for intensification (new hunting tools had already appeared before). It is not clear to what extent this is related, as it is not known how quickly the dingoes formed wild populations or how strongly they were tied to the indigenous people.

When this extinction actually took place is a matter of dispute; there are claims that a small population in northern Australia may have survived until after the arrival of Europeans. There are occasional claims of sightings on the mainland, but there is no evidence to support this.

extermination

In Tasmania , where dingoes never existed, the species was still widespread and common at the beginning of the 19th century. After sheep were introduced to the island, the thylacine received the reputation of a bloodthirsty hunter, although in reality most of the sheep were killed by feral domestic dogs. In 1830, the government put a pound bounty on each thylacine killed. In the 1860s, the species was restricted to the more inaccessible mountain regions in the southwest of the island; however, the hunt with traps and dogs continued unabated. Around 1910 the species was considered rare. Zoos all over the world went in search of these animals.

Although the species was kept in different zoos, there was only one litter in captivity in its history; which fell in 1899 at Melbourne Zoo. The last known killing of an animal in nature was in 1930; the last known specimen to date - an animal named Benjamin, who according to different assessments was a male or a female - died on the night of September 6th to 7th, 1936 in the now closed Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart in Tasmania. It had come to the zoo on February 19, 1924, with another thylacine who died on April 14, 1930. Benjamin, at 12 years and 4 months the longest living in human care, was dissected after his death and is now in the art gallery of the museum in Hobart.

There has also been speculation that disease contributed to the extinction of the thylacine. Evidence for this is a sudden decline in the number of animals shot around 1906, a simultaneous extinction spread across Tasmania and eyewitnesses who spoke of a disease similar to canine distemper . As with the other conjectures, there is no evidence of an epizootic cause of extinction here either; More recent model investigations come to the conclusion that such an event cannot in itself have been responsible for the extinction. DNA examinations of museum specimens provided evidence that the population living in Tasmania was heavily inbred , so that the lack of genetic diversity could also have contributed to the extinction.

Pouch wolves in zoos

Pouch wolves were not very popular with the audience, they only received attention during feeding, mating, rearing young animals or during strange behavior such as yawning angry, which was usually not understood as a threatening gesture. It is documented that 68 pouch wolves lived in zoos between 1850 and 1936, 18 of them were exported to other zoos during this time.

| place | Period | Copies |

|---|---|---|

| London | 1850-1931 | 20th |

| Hobart / Beaumaris | 1910-1936 | approx. 16 |

| Melbourne | 1864-1931 | approx. 15 |

| Adelaide | 1886-1903 | approx 8 |

| Washington | 1902-1909 | 5 |

| place | Period | Copies |

|---|---|---|

| Berlin | 1864-1908 | 4th |

| Sydney | 1885-1924 | 2 |

| Cologne | 1903-1910 | 2 |

| Paris | 1886-1891 | 2 |

| Antwerp | 1912-1914 | 1 |

| place | Period | Copies |

|---|---|---|

| Hobart / Wilmot | 1843-1846 | 3 |

| Launceston | 1879-1900 | 3 |

Protective measures

The protective measures that were taken to preserve the species came too late. In 1936, bag wolves were protected by law just before the last known bag wolves died in captivity. Several expeditions in the following decades found no more evidence that could indicate a survival of the species. In 1966, the Tasmanian government established a 647,000 hectare reserve in the southwest of the island in case some animals were still able to keep in retreat areas.

Current status

With a probability bordering on certainty, the pouch wolf has become extinct . However, there are repeated reports of sightings of live animals from Tasmania, but unambiguous photographs or video recordings of them do not exist. In March 2017, two independent alleged sightings on the Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland caused a stir. On March 22, 2005, the Australian magazine The Bulletin offered a reward of the equivalent of 750,000 euros for proving a live and uninjured animal.

Genome

In 2000, scientists began researching the animal's DNA , perhaps in order to be able to breed the extinct species again. Five years later they gave up the attempt: the genetic material available was too destroyed to be reconstructed. Among other things, the researchers had experimented with the DNA of a fetus that had been immersed in alcohol in 1886. Just three months later, however, Mike Archer from the University of New South Wales announced that the project would be continued by another group.

In 2007, Australian zoologists from the University of Adelaide's Australian Center for Ancient DNA wanted to begin DNA analysis of fecal samples collected during the 1950s and 1960s that could have been from the thylacine. This could help clarify the question of whether the thylacine may have survived significantly longer in the wild than previously thought.

In 2008, researchers from the University of Melbourne and the University of Texas succeeded in smuggling the col2A1 enhancer gene of the tassel wolf, isolated from tissue preserved in ethanol, into a transgenic mouse , where it was able to perform the function of the orthologous mouse gene in the mouse's cartilage cells . In 2009, another group sequenced the mitochondrial genome of the thylacine using samples from two museum exhibits.

In 2017, a group of Australian scientists led by Andrew J. Pask from the University of Melbourne succeeded in decoding the presumably complete genome of the thylacine. For this purpose, they extracted the DNA of a young animal that was still in the pouch at the time of its death and that had been immersed in alcohol in 1909 at the Victoria Museum in Australia. They received DNA fragments of 300 to 600 base pairs , which were isolated and sequenced. By comparing the overlapping sequences, they obtained a total sequence of 188 giga base pairs. This was compared with the databases for microbial and fungal DNA sequences. After subtracting these impurities, a total frequency of 155 Giga base pairs remained, which presumably corresponds to the somewhat complete genome of the pouch wolf. This assumption is supported by the comparison of the sequence extent of the genome of still living marsupial species such as the marsupial devil ( Sarcophilus harrisii ), with which the thylacine wolf ( Thylacinus cynocephalus ) shares around 89.3% of the genome.

The genome analysis also answers the phylogenetic position of the pouch wolf, which, like the numbat , belongs to the basal dasyuromorphia . The Tasmanian Wolf is only distantly related to the Tasmanian devil, which belongs to the Dasyuridae .

Systematics

The pouch-wolf was the only surviving member of the pouch-wolf family (Thylacinidae), which belongs to the order of the predator-like (Dasyuromorphia). The family itself has been documented since the Oligocene and is known to have numerous extinct genera. A short selection of types follows:

- Badjcinus turnbulli from the lower Oligocene may have corresponded to today's bag martens in shape and way of life. It was about ten inches long.

- Nimbacinus dicksoni lived in the lower Oligocene and the Miocene and reached a head body length of around 50 centimeters. Fossil remains have been found in Riversleigh, Queensland and the Northern Territory .

- Thylacinus potens lived around eight million years ago in the late Miocene. With a length of 150 centimeters and a weight of 40 kilograms, the species was somewhat larger than the later pouch wolf and also differed in its shorter, wider head.

Thylacine specimens in museums

The International Thylacine Specimen Database keeps records of all preparations of Thylacinus cynocephalus preserved worldwide . Most of the preparations are only in magazines because of their poor state of preservation or the fact that they are not very realistic. Specimens that are well preserved are now very popular with visitors.

There are assassin specimens to visit in:

Further preparations are exhibited in France, Italy, England, Russia, Australia and the USA.

Others

The Australian horror thriller Dying Breed , published in 2008, picks up on the myth of the poet wolf believed to be extinct.

In the 2011 Australian drama The Hunter , which is based on the novel of the same name by Julia Leigh ( Sleeping Beauty ), a hunter is said to locate an allegedly last sighted specimen of the Tasmanian tiger so that it can be cloned.

literature

- Heinz Moeller: The thylacine. Thylacinus cynocephalus. Westarp-Wissenschaften, Magdeburg 1997, ISBN 3-89432-869-X (Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei, Vol. 642).

- Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World . 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9 (English).

- Ronald Strahan: Mammals of Australia. Smithsonian Books, Washington (DC) 1996, ISBN 1-56098-673-5 .

Web links

- The Thylacine Museum - A wealth of information (English)

- The International Thylacine Specimen Database (English)

- Imaging the Thylacine - University of Tasmania exhibit

- The pouch wolf of the Natural History Museum Mainz

- 1935 film , latest film discovered, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, NFSA, May 20, 2020

- Thylacinus cynocephalus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008 Posted by: M. McKnight, 2008. Accessed on December 31 of 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Douglass S. Rovinsky, Alistair R. Evans, Damir G. Martin, Justin W. Adams: Did the thylacine violate the costs of carnivory? Body mass and sexual dimorphism of an iconic Australian marsupial. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287, 2020, S. 20201537, doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2020.1537

- ↑ a b Selina Bryan: Tasmanian tiger was no sheep killer .

- ↑ a b c d Selina Bryan: Tassie tiger not so menacing after all .

- ↑ Peter Savolainen, Thomas Leitner, Alan N. Wilton, Elizabeth Matisoo-Smith, Joakim Lundeberg: A detailed picture of the origin of the Australian dingo, obtained from the study of mitochondrial DNA. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, No. 33, 2004, pp. 12387-12390.

- ^ CN Johnson, S. Wroe: Causes of extinction of vertebrates during the Holocene of mainland Australia: arrival of the dingo, or human impact? In: The Holocene. Vol. 13, No. 6, 2003, pp. 941-948 ( summary )

- ^ A b Robert Paddle: The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The History and Extinction of the Thylacine . Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-53154-3 , pp. 199, 231 .

- ^ Stephen R. Sleightholme: Confirmation of the gender of the last captive Thylacine. Zoologist 35 (4), 2011, pp. 953-956

- ^ TA Prowse, CN Johnson, RC Lacy, CJ Bradshaw, JP Pollak, MJ Watts, BW Brook: No need for disease: testing extinction hypotheses for the thylacine using multi-species metamodels. In: The Journal of animal ecology. [electronic publication before going to press] January 2013, ISSN 1365-2656 . doi: 10.1111 / 1365-2656.12029 . PMID 23347431 .

- ↑ BR Menzies, MB Renfree, T. Heider, F. Mayer, TB Hildebrandt, AJ Pask: Limited genetic diversity preceded extinction of the Tasmanian tiger. In: PloS one. Volume 7, number 4, 2012, p. E35433, ISSN 1932-6203 . doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0035433 . PMID 22530022 . PMC 3329426 (free full text).

- ↑ Elle Hunt: 'Sightings' of extinct Tasmanian tiger prompt search in Queensland The Guardian , March 28, 2017, accessed on the same day (English)

- ↑ Researcher: Cloned Tasmanian tiger still a long way off . In: Vista Verde News . Vista Verde News , June 6, 2002, accessed April 20, 2008 .

- ↑ Researchers revive plan to clone tassie tiger . Sydney Morning Herald , accessed March 25, 2013

- ↑ Pask, AJ, RR Behringer & MB Renfree: Resurrection of DNA function in vivo from an extinct genome . In: PLoS ONE . 3, No. 5, 2008, p. E2240. doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0002240 . PMID 18493600 . PMC 2375112 (free full text).

- ^ Tasmanian tiger gene lives again Nature News, May 20, 2008

- ↑ Miller W, Drautz DI, Janecka JE, et al. : The mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tasmanian tiger ( Thylacinus cynocephalus ) . In: Genome Res. . 19, No. 2, February 2009, pp. 213-20. doi : 10.1101 / gr.082628.108 . PMID 19139089 . PMC 2652203 (free full text).

- ^ A b Andrew J. Pask: Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insights into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore. (PDF) In: Nature Ecology & Evolution. Nature, December 11, 2017, accessed December 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Dying Breed. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ↑ The Hunter. Retrieved July 2, 2012.