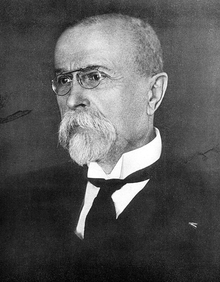

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (born March 7, 1850 in Hodonín , Moravia , † September 14, 1937 in Lány ) was a Czech philosopher , sociologist , writer and politician as well as co-founder and president of Czechoslovakia .

He is rarely given as Tomáš Masaryk . In the Czech Republic, its name is often abbreviated to TGM . He took the second name Garrigue after marrying the American industrialist daughter Charlotte Garrigue .

Masaryk was appointed professor of philosophy at Charles University in Prague in 1882 . When he called for a revision of the Hilsner case , he appeared in the Czech press against anti-Semitic prejudice. Masaryk, who was twice elected as a member of the Austrian Reichsrat , successfully campaigned for the establishment of an independent and democratic Czechoslovak state during the First World War, of which he was president from 1918 to 1935.

Life

origin

Tomáš Masaryk came from a humble background. He was the son of Jozef Masaryk, a Slovak coachman on imperial estates, and the Terezie Masaryková, née Kropáčková, a farmer's daughter and cook from Hustopeče . He later referred to his mother differently as German, Hannakin or Mährerin , and himself as a Czech, a Moravian or a Slovak. Despite this simple background, Masaryk was able to attend the German grammar school in Brno and later the academic grammar school in Vienna with the help of the then police director of Brno, Anton Ritter von Le Monnier .

There is speculation that Masaryk could have been the illegitimate son of a high-ranking person, possibly even the son of Emperor Franz Joseph , and was therefore intensely sponsored in his academic and professional career. In order to either verify or falsify the strong evidence of Franz Josef's paternity, a DNA comparison with material samples provided by the Masaryk Museum was planned for 2017. The investigation was not allowed by Masaryk's great-granddaughter Charlotta Kotík.

Academic career

From 1872 Masaryk studied philosophy at the University of Vienna , among others with Franz Brentano . After his doctorate on Plato , Masaryk went to Leipzig , where he studied with Wilhelm Wundt and had contact with Edmund Husserl . There he also met the American pianist Charlotte Garrigue , who he married in New York in 1878. Their five children together were the sociologist Alice Masaryková (* 1879), the painter Herbert Masaryk (* 1880), who died early, the diplomat and politician Jan Masaryk (* 1886), Eleanor (* 1890), who died in infancy, and Olga Masaryková (* 1891).

In 1878 Masaryk completed his habilitation in Vienna with a paper on suicide . As a young doctor of philosophy, he had also been given anatomy lessons in a private course held by the then student and later orthopedic surgeon Adolf Lorenz in Vienna. In 1879 Masaryk became a lecturer in Vienna, in 1882 an associate professor and in 1897 a full professor in Prague .

In 1886 he became known to the general public in one fell swoop when he intervened in the dispute over two manuscripts supposedly from the Middle Ages , but in reality forged at the beginning of the 19th century (the Königinhofer handwriting and the Grünberger handwriting ). As editor of the Athenaeum magazine , he let the opponents of the authenticity of these manuscripts have their say and vehemently advocated the opinion that the modern Czech nation should not refer to an invented past. He supported the linguist Jan Gebauer in demanding paleographic and chemical analyzes of the manuscripts.

In 1899, Masaryk defended the Jewish defendant Leopold Hilsner in one of the last ritual murder trials in Central Europe .

Political commitment

In 1887 he went into politics and founded a group called The Realists . In 1891 he was elected to the Austrian Reichsrat for the so-called Young Czechs , a Czech national party, but resigned again in 1893 because of differences of opinion with this party. In 1900 he founded the Realistic Party , for which he sat in the Reichsrat from 1907 to 1914.

With the outbreak of World War I , he pursued his plans for an independent Czechoslovak state and, without his intention, at the age of 64 became a key figure in the beginning Czech resistance struggle, which ended with the dissolution of Austria-Hungary . In September and October 1914 he made two conspiratorial trips to the Netherlands and in December 1914 another to Italy and Switzerland . In Switzerland he was warned that he would be arrested if he returned, so he stayed abroad with his daughter Olga. From Geneva he began to form an exile movement that was connected to the Prague underground, in which Czech politicians had come together in a secret society known as a " Maffie " to popularize the idea of state independence, and to the exile groups in France , Great Britain , the United States and Russia had to be coordinated.

In autumn 1915 Masaryk traveled via Paris , where Edvard Beneš was his closest colleague , to London as the political center of the Allies . On November 14, 1915, the Comité d'action tchèque à l'étranger , in which the foreign Czech organizations had come together, announced the establishment of an independent Czechoslovak state as their goal. The committee became the Czechoslovak National Council in February 1916 , with Masaryk as chairman. He succeeded in making the Czechoslovak question an international topic. On the initiative of Masaryk and the National Council, the Czechoslovak legions fighting on the side of the Allies were founded as an army in exile. Shortly after the Russian February Revolution in 1917 , Masaryk took over the organization of the local army in exile in May 1917. In December 1917, France allowed the establishment of a Czechoslovak army on its territory. From February 1918, the Allies saw the Czechoslovak army in Russia as part of the troops assembled in France. During his stay in Russia, Masaryk began writing his political program in Saint Petersburg , which he finished in the USA: The New Europe . First of all, it was intended to "make the fundamental problems of war clear to the soldiers".

From May to December 1918 Masaryk managed to convince the Allies to form a Czechoslovak state. France was the first allied to accept the Czechoslovak National Council as the basis of a future government on June 29, 1918, Great Britain followed on August 9, 1918, and the USA on September 3, 1918. In Paris, Edvard Beneš formed the previous National Council on October 14, 1918 as the provisional Czechoslovak government with Masaryk as Prime Minister. On October 18, 1918, Masaryk proclaimed an independent Czechoslovak state in the so-called Washington Declaration (see also the Pittsburgh Agreement ), invoking natural law , history and the democratic principles of the USA and France. The new state should be a republic with a parliamentary form of government, guaranteed basic rights of the citizens, the separation of church and state, universal suffrage, equal rights for women, minority protection and far-reaching social reforms such as the expropriation of large estates and the abolition of aristocratic privileges. On October 28, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian government accepted President Woodrow Wilson's terms for ending the war and offered an immediate armistice, making this day officially the founding day of the Czechoslovak Republic.

Presidency

On November 14, 1918, Masaryk was elected President of the Czechoslovak National Assembly, and on December 21, 1918 he returned to Czechoslovakia. As a result, all of Bohemia, Moravia and Austrian Silesia, as well as roughly the area of present-day Slovakia, were occupied by Czechoslovak and Allied troops as the territory of the new state of Czechoslovakia.

As an advocate of liberal and democratic humanism, he represented a moderate direction in the nationality conflicts, but was unable to persuade the agitators in the Czech five-party government to find a compromise with the large minorities of Germans , Slovaks , Hungarians and Ukrainians . In an interview given on January 10, 1919, before the start of the Paris peace negotiations , however, he expressed himself so ineptly that the German minority, especially occupied by Czech troops, was mainly using the terms “ de-Germanization ” and “foreigners” "Had to feel threatened:" (...) our historical boundaries quite coincide with the ethnographic boundaries. Only the north and west edges of the Bohemian quadrangle have a German majority as a result of the strong immigration during the last century. A certain modus vivendi will perhaps be created for these foreigners (French: “étrangers”) , and if they prove to be loyal citizens, it is even possible that our parliament (…) will grant them some kind of autonomy. I am also convinced that a very rapid de-Germanization of these areas will take place ”. Among other things, contrary to all promises of 1919, Czech remained the only state language.

Masaryk was re-elected a total of three times (1920, 1927 and 1934) and was for a long time the dominant figure in the new state. In terms of foreign policy, he leaned on Great Britain and France. After his resignation on December 14, 1935, Edvard Beneš succeeded him.

In the course of the stabilization of the Czechoslovak Republic from the mid-1920s, Masaryk, whose mother tongue was also German, acquired a certain reputation among parts of the Sudeten German population and thus became one of the few integrative factors of the new state, which on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of his death was also highlighted on Czech radio.

From 1927 Masaryk became involved in the informal regulars' group of Prague intellectuals Pátečníci , which met from 1925.

Effect as a philosopher

As a philosopher and staunch democrat, he developed some utopian ideas about the emergence of a “new person” through a better society. As a necessary basis for this he considered a Christian-social worldview, in which religion should be "free from the state and the arbitrariness of absolutist dynasties": " Jesus , not Caesar - this is the slogan of democratic Europe (...)." He was fundamentally suspicious of the state because it opposed the nation as a democratic organization. In the nation, every individual is called to show himself off; "The state is an aristocratic, coercive, oppressive organization: democratic states are only just emerging". The failure of these ideas in “his” country - not least because of the unsolved nationality problem - he did not live to see. Among many others, the author Max Brod , Thomas Mann and the philosopher and journalist Felix Weltsch were experts on Masaryk's writings. Masaryk has been nominated seventeen times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In 2002, the Swiss lawyer Radan Hain named TG Masaryk an outstanding but little-known figure in modern European history. In the meantime, for example, there is also a study in German by Dalibor Truhlar on Masaryk's philosophy of democracy (1994).

Honors

The Masaryk University in Brno , founded in 1919, bears his name, and the Automotodrom Brno motor racing circuit and its predecessor are known in the Czech Republic as Masaryk Ring ( Masarykův okruh in Czech ) . The oldest train station in Prague was named after him for the first time in 1919 and is still called Praha Masarykovo nádraží today . He was also instrumental in founding the School of Slavonic and East European Studies , part of the University of London .

Numerous squares and streets in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and other countries bear Masaryk's name. For example, the Avenida Presidente Masaryk in Mexico City , Masaryktown in Florida or the Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk in Israel are named after him.

In 2003, on the 85th anniversary of the founding of the Czechoslovak Republic, the Czechs named Masaryk, Jan Hus or Emperor Karl IV first in surveys after their greatest compatriot .

Fonts (selection)

- Suicide as a social mass phenomenon of modern civilization. 1881.

- D. Hume's Principles of Morality. 1883.

- D. Hume's skepticism and the principles of probability. 1884.

- Attempt a concrete logic. 1886.

- Česká otázka. Prague 1895 (the Czech question)

- Otázka sociální. Prague 1895 (the social question)

- Jan Hus. 1896.

- The philosophical and sociological foundations of Marxism . Vienna 1899.

- For correction [reply to Labriola]. In: The New Time. Volume I, 1899-1900, pp. 217-219 in response to Antonio Labriola: On the crisis of Marxism. In: The New Time. Volume I, 1899-1900, pp. 68-80.

- Rusko a Evropa. Prague 1913. (German: Russia and Europe. Studies on the spiritual currents in Russia. First part: On the Russian philosophy of history and religion. Sociological sketches. 2 volumes. Diederichs, Jena 1913)

- The new Europe. engl. and French 1918. (German 1922) FU Berlin

- Světová revoluce. Za války a ve válce 1914–1918. Prague 1925. (German: The world revolution. Memories and reflections. 1914–1918. Berlin 1927)

- The Making of a State. 1925. (English 1927)

Work editions

- Thomas Garrigue Masaryk: Works. 1930ff. (Czech)

literature

- Josef Hromádka : Masaryk's philosophy of religion and the foundations of scientific dogmatics. [ü Masaryk] Habilitation at the Hus Faculty in Prague 1920.

- Jan Herben : Thomas Garrigue Masaryk. 2 volumes. 1926 ( Czech )

- Sergi Bulgakov : What is the word? In: Festschrift Th. G. Masaryk, Bonn 1930, pp. 25–46.

- Festschrift for Th. G. Masaryk on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Bonn 1930.

- Josef Lukl Hromádka : Masaryk. 1930, Masaryk as European 1936.

- Johann Petrus: Thomas Garrigue Masaryk. From the bottom up. The life novel of a great man. Nordböhmischer Verlag, Reichenberg 1934.

- Oskar Kraus : Basics of Thomas Garrigue Masaryk's worldview. 1937.

- A. Werner: Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, picture of his life. 1937.

- W. Goldinger: Masaryk Thomas (Garrigue). In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 6, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-7001-0128-7 , p. 123 f. (Direct links on p. 123 , p. 124 ).

- Inocenc Arnošt Bláha : Krásný individualism. TG Masarykovi k šedesátým narozeninám. 1910, 1930.

-

Karel Čapek : Hovory s TG Masarykem also Hovory s TGM. three volumes, 1928–1935. (German: Masaryk tells his life. Conversations with Karel Čapek. Gutenberg Book Guild , Zurich 1934 - see more: Karel Čapek - German editions )

- Mlčení s TG Masarykem. 1935. (German silence with TG Masaryk , the fourth volume of the original trilogy, a subsequent sequel to Hovory's TG Masarykem )

- Otakar A. Funda : Thomas Garrigue Masaryk: His philosophical, religious and political thinking. Bern 1978.

- Radan Hain: State Theory and State Law in TG Masaryk's World of Ideas. Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-7255-3913-8 .

- Milan Machovec : Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. Graz 1969.

- Zdeněk Nejedlý : TG Masaryk I – IV. Prague 1931-1937.

- Zdeněk Nejedlý: Masaryk ve vývoji české společnosti a státu. 1950.

- Jaroslav Opat : Filozof a politik TG Masaryk 1882–1893. Příspěvek k životopisu. Praha 1990, ISBN 80-7023-044-4 .

- Jaroslav Opat: Průvodce životem a dílem TG Masaryka. Praha 2001, ISBN 80-86142-13-2 .

- Jan Patočka : Tři study o Masarykovi. Prague 1991.

- Alain Soubigou : Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. Praha, Litomyšl 2004, ISBN 80-7185-679-7 .

- Holm Sundhaussen : Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue , in: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe . Vol. 3. Munich 1979, pp. 112-114

- Dalibor Truhlar : Thomas G. Masaryk - Philosophy of Democracy. Frankfurt am Main 1994.

- Valentina von Tulechov: Tomas Garrigue Masaryk. His critical realism in terms of his understanding of democracy and Europe. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-89971-802-7 . (At the same time dissertation at the Munich University of Philosophy , 2010).

- Peter Diem : Tomáš G. Masaryk - From Reichsrat Member to Founder of the Czechoslovak Republic - Report on the MASARYK SYMPOSIUM on June 22, 2017 in Vienna. Platform Historia, June 22, 2017, accessed December 29, 2018 .

Web links

- Barry Smith: From TG Masaryk to Jan Patočka: A philosophical sketch. From: J. Zumr, T. Binder (eds.): TG Masaryk and the Brentano School. Akademie věd ČR, Graz / Prague 1993, pp. 94–110 (PDF, 148 kB)

- Literature by and about Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the German Digital Library

- Works by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the Gutenberg-DE project

- TG Masaryk on the Internet Archive

- Newspaper article about Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economy .

- Literature and other media by and about Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the catalog of the National Library of the Czech Republic

- Holdings at the Austrian National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Schamschula: History of Czech Literature II. From Romanticism to World War I Building blocks for the history of literature among the Slavs. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 1990, ISBN 3-412-02795-2 , p. 249.

- ↑ This is where Masaryk's studies began. ( Memento from November 11, 2011 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Landeszeitung. 08/2003.

- ↑ The Emperor and the Cook. on orf.at

- ↑ Explosive speculation: Was Masaryk a son of the Austrian emperor? on radio.cz

- ↑ Adolf Lorenz: I was allowed to help. My life and work. (Translated and edited by Lorenz from My Life and Work. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York) L. Staackmann Verlag, Leipzig 1936; 2nd edition, ibid. 1937, p. 90.

- ↑ Erich later : Villa Waigner. Hanns Martin Schleyer and the German elite of extermination in Prague 1939–1945. Konkret Literatur Verlag, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-930786-57-2 , p. 30.

- ↑ Jörg K. Hoensch : History of Bohemia: From the Slavic conquest to the present. 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-41694-2 , p. 410.

- ^ TG Masaryk: The new Europe. The Slavic point of view. Volk und Welt, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-353-00809-8 , p. 7.

- ↑ On Masaryk's political activity, cf. Radan Hain's account. ( Memento from October 17, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Une visite à Masaryk . In: Le Matin , Paris, January 12, 1919.

- ↑ See Masaryk on the 70th anniversary of his death

- ↑ Jan Bílek: Pátečníci u TGM v Lánech , in: Pražský hrad - programový čtvrtletník, online at: old.hrad.cz / ...

- ↑ Last sentence in his work Das neue Europa. The Slavic point of view. Volk und Welt, Berlin 1991, p. 201.

- ↑ TG Masaryk (1991), p. 54.

- ↑ Nomination Archive Nobel Prize

- ↑ Radan Hain on TG Masaryk ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Silja Schultheis on Masaryk veneration

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Masaryk, Tomáš |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder and first President of Czechoslovakia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 7, 1850 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hodonín |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 14, 1937 |

| Place of death | Lány |