Knowledge management

Knowledge management [ -mænɪdʒmənt ] ( English knowledge management ) is a comprehensive term for all strategic or operational activities and management tasks that aim at the best possible use of knowledge . Contributions to knowledge management - theoretical as well as practical-application-oriented kind - are developed in many disciplines, especially in business administration , computer science , information science , social science , education or business informatics .

Individual versus structural knowledge

definition

Knowledge management is the methodical influence on the knowledge base of a company (organizational knowledge management) or an individual ( personal knowledge management ). The knowledge base is understood to mean all data and information , all knowledge and all skills that this organization or person has or should have to solve its diverse tasks .

In organizational knowledge management, individual knowledge and skills ( human capital ) should be systematically anchored at different levels of the organizational structure. Organizational knowledge management can therefore be understood as intervening action that is based on the theories of organizational theory and organizational learning and aims to systematically translate these into practice.

As a result of today's knowledge and innovation-oriented communication age, the knowledge capital available in the company is increasingly becoming a decisive production factor . The knowledge within a company is thus understood as a production factor that occurs alongside capital , labor and land . The strategic basis for knowledge management provides especially the knowledge-based theory of the firm ( English Knowledge-Based View of the Firm ). This represents an expansion of the view of seeing information (e.g. in the context of market design and influencing) as an operational resource or as a production factor .

Information systems usually form a central element in that they network employees in a communicative manner and provide and store information.

Scientists criticize the knowledge management approach above all for an undifferentiated concept of knowledge, which is often not sufficiently differentiated from the concepts of “data” and “information”. Furthermore, an objectively inappropriate or even paradoxical understanding of the production factor concept is criticized, as v. a. This is reflected in the talk of the “immaterial resource knowledge”, as well as a one-sided orientation towards certain older mechanistic concepts of control and feasibility, some of which have already been revised by modern management theory. The legal question of to what extent and under what conditions organizations (including commercial enterprises) can claim exploitation of the individual knowledge of their members (employees) is also unresolved . Such stocks of knowledge are first of all to be regarded as the (often expensive) intellectual property of their bearers. This fact is supported in free and democratic societies generally reflects these considerations between employers and workers labor contracts are closed, while the right to exploit the employers paid payment manpower , but not at the same time the knowledge of their employees attach. On such problems some authors occurs according to an ideological bias ( bias ) of the knowledge management approach to light, which tends always a theoretical viewing perspective with a practical mix of action and design perspective - a charge that recently against numerous "fashions and Myths of Management ”( Alfred Kieser ) has been raised.

Regardless of all objections, the board members of many companies have been expanded to include the position of Chief Information Officer ( CIO ) with a focus on information management , who is responsible for coordinating the information processing of a company with its overall strategy. The objectives of practical knowledge management go well beyond simply providing employees with information:

- Employees should be able to develop qualifications and skills by learning and use them to add value.

- The classification knowledge is performed in two expression Poland: on the one hand so-called. Codified knowledge ( Explicit knowledge ) that can be described and is therefore suitable to be held in documents, and on the other hand, implicit knowledge that can not be or is not brought profitably in codifiable form can.

These two extreme forms correspond to the two fundamental strategies of knowledge management, which are referred to in English as " people-to-document " ( codification ) and " people-to-people " ( tacit knowledge ). To pass on tacit knowledge, different approaches and methods are required than in the area of “ (bring) people-to-document (s) ”, where solution scenarios based primarily on database and document management are available.

The distinction between explicit vs. Tacit knowledge - and the fundamental focus of the knowledge management strategy to be derived from it - are particularly important in business application areas (companies), because it is precisely here that the business restrictions come into full effect: Real expert knowledge, e.g. B. has a strong tendency to combine extreme complexity with a rather short period of validity - and: the more something is expert knowledge, the more pronounced these two combination factors (high complexity and short duration) are. In a business context, however, it is neither sensible nor possible to use this implicit knowledge for codification ( documentation ), especially since hardly anyone on the recipient side would have the time to read this certainly very extensive documentation.

Conversely, that means nothing else than: Standard content is more suitable for a people-to-document strategy ( database , document management , etc.) - not very complex and with a long period of validity.

Knowledge acquisition

The acquisition and processing of knowledge is of great importance in the context of knowledge management, see also intellectual capital statement . There are three components here:

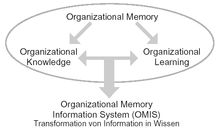

- Organizational Memory (English organizational memory )

- The organizational memory is the entirety of the components for knowledge acquisition (acquisition), knowledge processing ( maintenance ) and knowledge use ( search and retrieval , see also research ).

- Organizational Knowledge

- This includes the current knowledge of an organization and is often reflected in knowledge databases.

- Organizational Learning ( learning organization )

- This deals with the reproduction of organizational knowledge, e.g. B. through enterprise wikis .

Before implementing knowledge management in an organization, an information needs analysis is useful (Mujan 2006). Since the full range of knowledge management tools cannot be implemented in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (especially for reasons of cost), information needs analyzes are absolutely necessary for SMEs (Gust von Loh 2008).

Control versus creativity

Instructions mean something different to humans than they do to computers . Many authors (including Georg von Krogh ) believe that knowledge cannot be managed at all because management includes control, but knowledge is also based on the creative use of context and associations that are hindered by control.

Models

Knowledge management according to Nonaka and Takeuchi

As co-founder of knowledge management, the Japanese can Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi with its 1995 published book The Knowledge Creating Company (German in 1997 as the organization of knowledge are) considered. Building on the concept of tacit knowledge introduced by Michael Polanyi in 1966 , they design a model in which knowledge is generated in a continuous transformation between tacit and explicit knowledge. Through successive processes of "externalization" (implicit to explicit), "combination" (explicit to explicit), "internalization" (explicit to implicit) and "socialization" (implicit to implicit), knowledge within an organization is spiraling up from individual knowledge higher organizational levels such as groups of people and entire companies. This model, known as the SECI model, has had a major impact on the following literature and research on knowledge management. In 2004 Nonaka and Takeuchi defined knowledge management as follows: "knowledge management is defined as the process of continuously creating new knowledge, disseminating it widely through the organization, and embodying it quickly in new products / services, technologies and systems". (German: Knowledge management is the process of the continuous generation of knowledge, its wide organizational dissemination, and its rapid embodiment in new products, services and systems)

Features of knowledge management according to Probst / Raub / Romhardt

The building blocks of knowledge management are a common model and an easy to use method to manage knowledge. The method provides 8 modules, 6 of which form the core processes of knowledge management, in order to give these core processes an orienting and coordinating framework, 2 modules (knowledge goals, knowledge assessment) were added. The 6 core processes (building blocks) form the “inner” cycle, the strategic the “outer” cycle. These 8 building blocks are:

- Knowledge goals

- They give direction to knowledge management. They determine at which levels and which skills are to be developed. A distinction is made between normative knowledge goals (these have an effect on the corporate culture ), strategic (they are aimed at the future competence requirements of the organization) and operational knowledge goals that focus on concrete implementation.

- Knowledge identification

- This module is about creating transparency about the internal and external knowledge environment of a company, this includes internal and external data, information and skills. Many companies find it difficult to keep track of internal and external data, information and skills. For this reason, effective knowledge management must enable sufficient internal and external transparency and support individual employees in their search activities.

- Knowledge acquisition

- By recruiting experts or acquiring particularly innovative companies, companies can buy know-how that they cannot develop on their own. To put it somewhat casually: buy in or develop yourself?

- Knowledge development

- Knowledge development is a supplementary building block for knowledge acquisition. The knowledge that is not to be covered by the knowledge acquisition module must be developed internally.

- Knowledge distribution

- The key question is: Who should know what or to what extent, and how can the processes of knowledge (distribution) be facilitated? There are a variety of methods for this, such as: Lessons Learned , After Action Review , Workshops , Jour fixe , mentoring principle , newsletters and much more.

- Knowledge use

- Use is the productive use of organizational knowledge.

- Knowledge retention

- In order to obtain valuable specialist knowledge, it is necessary to design usable selection processes and then to save and update them appropriately.

- Knowledge assessment

- The focus here is on achieving the knowledge goals.

Ideally, the building blocks are processed in a cycle, in the above order of the building blocks, based on the knowledge goals, with the findings from the knowledge assessment flowing back into the building block knowledge goals. In reality there is a strong interlinking of the core processes.

Business process-oriented knowledge management

Business process- oriented knowledge management aims to focus knowledge and activities of knowledge management on the business processes of a company. In this way, an integration into the everyday work of employees is achieved at the same time. The approach is represented by Norbert Gronau ( University of Potsdam ), Holger Nohr ( Stuttgart Media University ), Andreas Abecker ( Research Center for Computer Science ) or Peter Heisig and the Fraunhofer IPK .

Knowledge management can be viewed in a process-oriented manner in several ways (Holger Nohr 2004):

- Knowledge management in the narrower sense can be viewed as a classic (knowledge) management process that sets the framework for individual or combined knowledge processes (e.g. identification, search, distribution or use of knowledge).

- A second view looks at the knowledge-based design process of business processes, whereby process knowledge is generated and applied.

- The third perspective of business process-oriented knowledge management deals with the integration of functional knowledge into the implementation of business processes and the connection of knowledge processes to business processes.

This approach is based on the knowledge-oriented modeling of business processes (e.g. with the KMDL or with the help of extended XML networks) and the use of application systems (e.g. workflow management systems ).

Knowledge engineering

The task of knowledge engineering is to map the complexity of world and expert knowledge on a regular structure andto present it tothe user in computer-aided applications in an intelligent information system. This area of knowledge management comprises four central categories in dealing with human information :

- Acquisition of knowledge

- Structuring and formulaic representation

- Illustration of knowledge in the computer

- System design and architecture

- Computer-based processing of knowledge

- Combination of explicit knowledge, problem solving and generating results

- Presentation of knowledge

- Presentation in terms of interactive applications by the user, e.g. B. the creation of views (" Views ") on content (" Content ")

Knowledge market

The concept of the knowledge market ( Engl . Knowledge Market ) is based on the assumption that interesting for a company knowledge (eg. As competences of the employees or customer information) is a scarce resource and therefore has a market value. Knowledge is a resource that does not diminish through use and when shared with others, but rather increases. Therefore knowledge can be developed and used competitively both within a company and across companies.

In a knowledge market, the information offered is difficult to compare with one another. The relationships between knowledge providers and knowledge seekers are often of a personal nature (initiators, coaches, sponsors or knowledge managers ) and are based on long-term trust. For the knowledge buyer who buys knowledge from outside, this trust is of central importance, as he does not always have the possibility to assess the quality of the services offered.

According to K. North, the concept of knowledge management is based on the design of necessary organizational framework conditions and sees the goal in the development of market mechanisms that should lead to a balance between the supply of knowledge and the demand for knowledge. The advantages of this model lie in the self-regulation of the emerging knowledge market.

In practice, this means that a suitable mix of personalization and codification (where the knowledge can be looked up, e.g. database, quality manual, checklists, process flow, etc.) must be found. Three conditions are indispensable for the development and transfer of knowledge from or in companies in the sense of a good knowledge market:

- Requirements for the corporate environment

- With the positive development of the company or business units, a solid corporate mission statement , management principles (management by methods) and an attractive incentive system must be established and coupled.

- Rules of interaction

- The knowledge market works just like all other markets, namely through suppliers and buyers. These define the way (definition of the rules of the game) for the knowledge market. It is therefore necessary that the rules of the game are laid down and generally articulated.

- Organizational structure for knowledge generation

- The implementation of knowledge development and knowledge transfer require a medium (e.g. through a knowledge map , employee workshops , expert communities, online assessment or traditionally using the interview method). Through internal benchmarking , the different best practices can be compared and the existing competencies introduced into knowledge markets.

Approaches to maturity assessment

Maturity models for knowledge management pursue the goal of a holistic qualitative or quantitative assessment of knowledge management activities and processes in an organization. Recommendations for action to achieve a higher level of maturity can then be derived on this basis. Existing maturity models for knowledge management are usually based on the Capability Maturity Model for Software ( CMMI ), a five-stage process model for the quantitative assessment and improvement of the maturity of software development processes in organizations, or on its European counterpart SPICE . There are currently some theoretical maturity models, some of which are also supported by appropriate tools, for assessing the WM maturity level, such as Berztiss' Capability Maturity for KM, Kochikar's Knowledge Management Maturity Model or the Knowledge Process Quality Model (KPQM).

Knowledge Process Quality Model

The Knowledge Process Quality Model ( KPQM ) by Oliver Paulzen and Primoz Perc was developed for the maturity assessment of knowledge processes and serves as support for knowledge managers . KPQM describes the development of process maturity on six stages, which are examined using four development paths. With the help of the detailed specification of necessary activities and results, a direct derivation of prioritized measures for knowledge management is possible from the evaluation results.

Maturity levels:

- 0 initial

- 1 Conscious

- 2 Controlled

- 3 Standardized

- 4 Quantitatively controlled

- 5 Continuous improvement

At each maturity level, the following development paths are considered to examine the knowledge processes:

- Process organization

- Employee engagement and knowledge networks

- Acceptance and motivation

- Computer-based support

Process attributes (e.g. training of employees and managers ) that are assigned to each maturity level and each development path are used for the detailed evaluation of the processes.

The basic idea of the model is based on the SPICE model ( Software Process Improvement and Capability Determination ) from software development and takes into account the special features of knowledge management through the inclusion of specific knowledge management models.

Methods

Knowledge management methods and instruments support the concrete implementation of knowledge goals in the company. Heiko Roehl, for example, provided a comprehensive overview or classification of knowledge management instruments according to partially overlapping functional groups. A distinction is made here between personal, problem-solving, communication-related, work-related and technical infrastructure related instruments. Selected instruments and methods are presented below:

- Planning methods

- Representation methods

- Creativity methods , see also brainstorming

-

Methods of promoting knowledge

- Lessons learned

- Best practice sharing

- Dialogic procedures

-

Methods of organization

- Communities of Practice (set up and manage)

- Valuation methods

- Storage Methods

techniques

- Groupware systems

- Social software

- Content-oriented systems

- Systems of artificial intelligence

- Expert systems

- Agent systems

- Text mining systems

-

Management information systems

- Data warehouse systems

- OLAP systems

- Data mining

- Other systems

These techniques can also be integrated in a system so that, for example, a company uses a knowledge management system based on an intranet . Several components such as a content management system , a document management system and a search function via a search engine can be implemented in this intranet .

Current topics in knowledge management

- Measure and manage knowledge, e.g. B. through the intellectual capital statement, knowledge audit , balanced scorecard , or the Skandia Navigator .

- Social networks , competence networks and communities of practice

- Organizational structure & knowledge management (knowledge market), organizational structure for knowledge generation, hypertext organization , starting points for designing a knowledge-oriented organizational structure

- Knowledge management and Web 2.0 - use of social software such as wikis and blogs in knowledge management

- Standardization of knowledge management (DIN)

- Knowledge transfer, e.g. B. Protection against loss of knowledge by leaving employees, see also demographic change

- Knowledge extraction, structuring and storage based on approaches from the Semantic Web

- Knowledge management best practices

- Success factors, benefits and sustainability of knowledge management approaches

- Create awareness of the relevance of knowledge management

- Knowledge culture , e.g. B. Influence of corporate culture on knowledge transfer, starting points for designing a knowledge-oriented organizational culture

See also

- Opportunity management

- Community of Knowledge

- Enterprise content management

- Technical information

- Common knowledge construction

- Knowledge Management Society

- Collaborative writing

- Competence management

- Learning organization

- Link management

- Organizational intelligence

- Strategic management

- Talent management

- Knowledge-based company view

literature

- A. Abecker, K. Hinkelmann, H. Maus, HJ Müller (eds.): Business process-oriented knowledge management . Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 2002, ISBN 3-540-42970-0 .

- E. Bäppler: Use of knowledge management in strategic management. For interdisciplinary links through the use of ICT . Gabler, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-1438-5 .

- T. Davenport: Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know . Mcgraw-Hill Professional, 2000, ISBN 1-57851-301-4 .

- S. Eschenbach, B. Geyer: Knowledge & Management - 12 concepts for dealing with knowledge in management. Linde International, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7143-0020-1 .

- W. Kreitel: Resource Knowledge: Successfully introduce and use knowledge-based project management. With recommendations and case studies . Gabler, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-0448-5 .

- K. Lenk, U. Meyerholt, P. Wengelowski: Managing knowledge in the state and administration . sigma, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-89404-844-0 .

- I. Nonaka, H. Takeuchi: The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation . Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-19-509269-4 .

- K. North: Knowledge-oriented corporate management: Value creation through knowledge . Gabler, 2005, ISBN 3-8349-0082-6 .

- Tilo Pfeifer, Gabriele Vollmar: Knowledge Management. In: Tilo Pfeifer, Robert Schmitt (Hrsg.): Masing handbook quality management . 6th, revised edition. Carl Hanser Fachbuchverlag, Munich / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-446-43431-8 , chapter 13.

- G. Probst, St. Raub, K. Romhardt: Managing Knowledge - How Companies Use Their Most Valuable Resource . Gabler, 2006, ISBN 3-8349-0117-2 .

- W. Sarges: Skill Management - Different Relevance of Knowledge Management. In: M. Bellmann, H. Krcmar , T. Sommerlatte (eds.): Practical handbook knowledge management - strategies, methods, case studies. Symposion, Düsseldorf 2005, pp. 529-548.

- H. Willke: Systemic Knowledge Management . UTB, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8252-2047-8 .

Web links

- Literature on knowledge management in the catalog of the German National Library

- What is knowledge management? (available under the Creative Commons license) Community of Knowledge, website about knowledge management

- Karl M. Wiig: Knowledge Management: An Emerging Discipline Rooted in a Long History. (1999; PDF; 162 kB)

- Konrad Paul Liessmann : Why you can't manage knowledge. ( Memento from June 28, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) 2006.

- Rafael Capurro: Can knowledge be managed? An information science perspective. 2001.

- TD Wilson: The nonsense of "knowledge management". 2002.

- Christian Schilcher: Implicit dimensions of knowledge and their importance for corporate knowledge management. Dissertation. 2006.

- Sibylle Schneider: Knowledge management and the "human factors". 2004.

- Knowledge management process systematics - guidelines of the BITKOM association : Systematic compilation of knowledge management processes / instruments, for free download even for non-BITKOM members

- Open Journal of Knowledge Management : Awards German and English language submissions on knowledge management (available free of charge under a Creative Commons license)

- Gabi Reinmann : Study text knowledge management 2009. (PDF; 1.2 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wivu transfer: Knowledge at the right time in the right place - is that possible? , in: UdZ - Company of the Future, FIR magazine for business organization and business development. Volume 10, Issue 3/2009, ISSN 1439-2585 , pp. 17-19. wivu-transfer.ebcot.info ( Memento from May 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ B. Meyer, K. Sugiyama: The concept of knowledge in KM: a dimensional model. In: Journal of Knowledge Management. 11 (1), 2007, pp. 17-35.

- ↑ JP Walsh, GR Ungson: Organizational Memory. In: Academy of Management Review. Vol. 16, 1991, pp. 57-91; Quoted in: Kevin Daniels: Putting Process into Strategy. The Open University, Milton Keynes 2002, ISBN 0-7492-9273-3 .

- ↑ Sonja Gust von Loh: Knowledge management and information needs analysis in small and medium-sized companies. In: Information - Science and Practice. 59 (2), 2008, pp. 118-126. wwwalt.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de (part 1) and 127–136 wwwalt.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de (part 2).

- ↑ Hirotaka Takeuchi, Ikujirō Nonaka: Hitotsubashi on knowledge management. Wiley, Singapore 2004, p. IX.

- ↑ G. Probst, St. Raub, K. Romhardt: Managing knowledge - How companies use their most valuable resource. Gabler, 2006, p. 25 ff.

- ↑ Holger Nohr: Knowledge Management. In: R. Kuhlen, T. Seeger, D. Strauch (eds.): Basics of practical information and documentation. Volume 1: Introductory Guide to Information Science and Practice. 5th edition. Saur, Munich 2004, pp. 257-270.

- ^ K. North: Knowledge-oriented corporate management. ISBN 3-8349-0082-6 , p. 259 ff.

- ↑ AT Berztiss: Capability Maturity for Knowledge Management, 13th International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications (DEXA'02), Aix-en-Provence, France, 2002.

- ↑ VP Kochikar: The Knowledge Management Maturity Model: A Staged Framework for Leveraging Knowledge, KMWorld 2000. Santa Clara, CA, 2000.

- ^ The Tenth Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2006). P. 403, accessed on July 31, 2012.

- ^ Heiko Roehl: Tools of the knowledge organization. Perspectives for a differentiating intervention practice. In: German University Publishing House. 2000.

- ^ K. North: Knowledge-oriented corporate management. ISBN 3-8349-0082-6 , p. 259 ff.

- ↑ H.-G. Schnauffer, B. Stieler-Lorenz, S. Peters: Networking Knowledge - Knowledge Management in Product Development. Springer, Berlin, pp. 12-45.

- ↑ M. Staiger: Knowledge Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises - Systematic Design of a Knowledge-Oriented Organizational Structure and Culture. Hampp, Munich 2008, p. 84 ff.

- ↑ AE Katzung, R. Fuschini, M. Wunram: ExTra (Expertise Transfer) - knowledge assurance at AIRBUS. In: VDI reports. 1964, pp. 243-266.

- ↑ Managing engineering knowledge effectively: Conference Berlin, September 14th and 15th, 2006. VDI Verlag, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 3-18-091964-7 .

- ↑ Company threatens to lose knowledge. In: FAZ. October 19, 2006, berufundchance.fazjob.net

- ↑ M. Staiger: Knowledge Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises - Systematic Design of a Knowledge-Oriented Organizational Structure and Culture. Hampp, Munich 2008, p. 139 ff.

- ↑ F. Kragulj: knowledge management and organizational culture - presentation, linked and views of an integrated model hypothesis. Vienna University of Economics and Business, 2010.