Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, Jr. (born May 8 1937) is an American writer based in New York City. He is noted for his dense and complex works of fiction. Born in New York (on Long Island), Pynchon spent two years in the United States Navy and earned an English degree from Cornell University. After publishing several short stories in the late 1950s, he began composing the novels for which he is best known today: V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), Gravity's Rainbow (1973), Vineland (1990), and Mason & Dixon (1997).

Pynchon is widely acclaimed as among the finest of contemporary authors. He is a MacArthur Fellow and a recipient of the National Book Award, and is regularly cited as a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Both in fiction and non-fiction his writing encompasses a vast array of subject matter, styles and themes, including the fields of history, science and mathematics. Pynchon is also known for his avoidance of publicity: very few photographs of him have ever been published, and rumors about his location and identity have circulated since the 1960s.

Biography

Thomas Pynchon was born in 1937 in Glen Cove, Long Island, New York to Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, Sr., and Katherine Frances Bennett Pynchon. His earliest American ancestor, William Pynchon, emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, and thereafter a long line of Pynchon descendants found wealth and repute on American soil. Pynchon's family background and aspects of his ancestry have provided source material for his fictions, particularly in the Slothrop family histories related in "The Secret Integration" (1964) and Gravity's Rainbow.

Childhood and education

Pynchon attended Oyster Bay High School, where he wrote for the school newspaper and excelled in his studies. After graduating in 1953, he studied engineering physics at Cornell University, but left at the end of his second year to serve in the U.S. Navy. In 1957 Pynchon returned to Cornell to pursue a degree in English. His first published story, "The Small Rain", appeared in the Cornell Writer in May 1959, and narrates an actual experience of a friend who had served in the army; subsequently, however, episodes and characters throughout Pynchon's fiction draw freely upon his own experiences in the navy.

While at Cornell, Pynchon became a close friend of Richard Fariña, and both briefly led what Pynchon has called a "micro-cult" around Oakley Hall's 1958 novel Warlock. (He later reminisced about his college days in the introduction he wrote in 1983 for Fariña's novel Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, first published in 1966.) Pynchon also reportedly attended lectures given by Vladimir Nabokov, who then taught literature at Cornell. While Nabokov later said that he had no memory of Pynchon (though Nabokov's wife, Vera, who graded her husband's class papers, commented that she remembered his distinctive handwriting), other of Pynchon's lecturers at Cornell recall him as being a gifted and exceptional student. Pynchon received his BA in June 1959.

Early career

After leaving Cornell, Pynchon began to work on his first novel. From February 1960 to September 1962 he was employed as a technical writer at Boeing in Seattle, where he compiled safety articles for the Bomarc Service News (see Wisnicki 2000-1), a support newsletter for the BOMARC surface-to-air missile deployed by the U.S. Air Force. Pynchon's experiences at Boeing inspired his depictions of the "Yoyodyne" corporation in V. and The Crying of Lot 49, and both his background in physics and the technical journalism he undertook at Boeing provided much raw material for Gravity's Rainbow. When it was published in 1963, Pynchon's novel V. won a William Faulkner Foundation Award for best first novel of the year.

After resigning from Boeing, Pynchon spent time in New York and Mexico before moving to California, where he was reportedly based for much of the 1960s and early 1970s, most notably in an apartment in Manhattan Beach (see Frost 2003). In 1964 his application to study mathematics as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, was turned down (Royster 2005). In 1966 he wrote a first-hand report on the aftermath and legacy of the Watts riots in Los Angeles. Entitled "A Journey Into the Mind of Watts", the article was published in the New York Times Magazine (Pynchon 1966).

Pynchon's second novel, The Crying of Lot 49, is also set in California. It was published in 1966, and won the Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award. Although it is more concise and linear in its structure than Pynchon's other novels, its labyrinthine plot features an ancient, underground mail service known as "The Tristero" or "Trystero", a parody of a Jacobean revenge drama entitled The Courier's Tragedy, and a corporate conspiracy involving the bones of World War II American GIs being used as charcoal cigarette filters. It proposes a series of seemingly incredible interconnections between these and other similarly bizarre revelations that confront the novel's protagonist, Oedipa Maas. Like V., the novel contains a wealth of references to science and technology and to obscure historical events, and both books dwell upon the detritus of American society and culture. The Crying of Lot 49 also continues Pynchon's habit of composing parodic song lyrics and punning names, and referencing aspects of popular culture within his prose narrative. In particular, it incorporates several allusions to Nabokov's Lolita.

Gravity's Rainbow and Pynchon's rise to prominence

Pynchon's most celebrated novel is his third, Gravity's Rainbow, published in 1973. An incredibly intricate and allusive fiction which combines and elaborates on many of the themes of his earlier work, including preterition, paranoia, racism, colonialism, conspiracy, synchronicity, and entropy, the novel has spawned a wealth of commentary and critical material, including two reader's guides (Fowler 1980; Weisenburger 1988), books and scholarly articles, on-line concordances and discussions, and art works, and is regarded as one of the archetypal texts of American literary postmodernism. The major portion of Gravity's Rainbow takes place in London and Europe in the final months of the Second World War and the weeks immediately following VE Day, and is narrated for the most part from within the historical moment in which it is set. In this way, Pynchon's text enacts a type of dramatic irony whereby neither the characters nor the various narrative voices are aware of specific historical circumstances, such as the Holocaust, which are, however, very much to the forefront of the reader's understanding of this time in history. Such an approach generates dynamic tension and moments of acute self-consciousness, as both reader and author seem drawn ever deeper into the "plot", in various senses of that term. Encyclopedic in scope, the novel also displays enormous erudition in its treatment of an array of material drawn from the fields of psychology, chemistry, mathematics, history, religion, music, literature and film. Perhaps appropriately for a book so suffused with engineering knowledge, Pynchon reputedly wrote the first draft of Gravity's Rainbow in longhand on engineer's graph paper, in California and Mexico City.

Gravity's Rainbow was a joint winner of the 1974 National Book Award for Fiction, along with Isaac Bashevis Singer's A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories. In the same year, the fiction jury unanimously recommended Gravity's Rainbow for the Pulitzer Prize, however, the full Pulitzer panel vetoed the decision, describing the novel as "unreadable", "turgid", "overwritten", and in parts "obscene". The jurors refused to amend their recommendation, and as a result no fiction prize was awarded that year (Kihss 1974). In 1975, Pynchon declined the William Dean Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Post-Gravity's Rainbow

A collection of Pynchon's early short stories, entitled Slow Learner, was published in 1984, with a lengthy autobiographical introduction. Pynchon's fourth novel, Vineland, was published in 1990, and was regarded as a disappointment by the majority of reviewers and critics. The novel is set in California in the 1980s and 1960s, and describes the relationship between an FBI COINTELPRO agent and a female radical filmmaker. Its strong socio-political undercurrents detail the constant battle between authoritarianism and communalism, and the nexus between resistance and complicity, but with a typically Pynchonian sense of humor.

In 1988, he received a MacArthur Fellowship and, since the early 1990s at least, many observers have mentioned Pynchon as a Nobel Prize contender (see, for example, Grimes 1993; CNN Book News 1999; Ervin 2000). Renowned American literary critic Harold Bloom has named him as one of the four major American novelists of his time, along with Don DeLillo, Philip Roth, and Cormac McCarthy.

Pynchon's most recent novel is Mason & Dixon, a work which had been in the pipeline since 1978 at least (Roeder 1978; see also Ulin 1997). Published in 1997, the meticulously-researched novel is a sprawling postmodernist saga recounting the lives and careers of the English astronomer, Charles Mason, and his partner, the surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, and the birth of the American Republic. While it received some negative reviews, the great majority of commentators acknowledged it as a welcome return to form.

It has been rumored that Pynchon's next book will be about the life and loves of Sofia Kovalevskaya, whom he allegedly studied in Germany. The former German minister of culture Michael Naumann has stated that he assisted Pynchon in his research about "a Russian mathematician [who] studied for David Hilbert in Göttingen". No reliable information about the novel's date of publication has so far been forthcoming.

Themes and influence

Along with its emphasis on loftier themes such as racism, imperialism and religion, and its cognizance and appropriation of many elements of traditional high culture and literary form, Pynchon's work also demonstrates a strong affinity with the practitioners and artifacts of low culture, including comic books and cartoons, pulp fiction, popular films, television programs, cookery, urban myths, conspiracy theories and folk art. This blurring of the conventional boundary between "High" and "low" culture, sometimes interpreted as a "deconstruction", is seen as one of the defining characteristics of postmodernism.

In particular, Pynchon has revealed himself in his fiction and non-fiction as an aficionado of popular music. Song lyrics and mock musical numbers appear in each of his novels, and in his autobiographical introduction to the Slow Learner collection of early stories he reveals a fondness for both jazz and rock and roll. The character McClintic Sphere in V. is a fictional composite of master jazz musicians such as Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk. In The Crying of Lot 49, the lead singer of "The Paranoids" sports "a Beatle haircut" and sings with an English accent. In the closing pages of Gravity's Rainbow there is an apocryphal report that Tyrone Slothrop, the novel's protagonist, played kazoo and harmonica as a guest musician on a record released by The Fool in the 1960s (having magically recovered the latter instrument, his "harp", in a German stream in 1945, after losing it down the toilet in 1939 at the Roseland Ballroom in Roxbury, Boston, to the strains of the jazz standard 'Cherokee', upon which tune Charlie Parker was simultaneously inventing bebop in New York, as Pynchon describes). In Vineland, both Zoyd Wheeler and Isaiah Two Four are also musicians; Zoyd played keyboards in a '60s surf band called "The Corvairs", while Isaiah plays in a punk band called "Billy Barf and the Vomitones". In Mason & Dixon, one of the characters plays on the "Clavier" the varsity drinking song which will later become "The Star-Spangled Banner".

In his Slow Learner introduction, Pynchon also acknowledges a debt to Spike Jones; later, Pynchon penned the liner notes for Spiked, a collection of Jones's music. He also wrote the liner notes for Nobody's Cool, the second album of indie rock band Lotion, in which he states that "rock and roll remains one of the last honourable callings, and a working band is a miracle of everyday life. Which is basically what these guys do." He is also known to be a fan of Roky Erickson.

In terms of literary influences and affinity, an eclectic catalogue of Pynchonian precursors has been proposed by readers and critics. Beside overt references in the novels to writers as disparate as Henry Adams, Giorgio di Chirico, Emily Dickinson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ishmael Reed, Patrick O'Brian and Umberto Eco, credible comparisons with works by Rabelais, Laurence Sterne, Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Mann, Jorge Luis Borges, William Burroughs, Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison have also been made. Some commentators have detected similarities with those writers in the Modernist tradition who wrote extremely long novels dealing with large metaphysical or political issues. Examples of such works might include Ulysses by James Joyce, A Passage to India by E.M. Forster, The Apes of God by Wyndham Lewis, The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil, or The Castle by Franz Kafka. In his 'Introduction' to Slow Learner, Pynchon explicitly acknowledges his debt to Beat Generation writers, and expresses his admiration for Jack Kerouac's On the Road in particular; he also reveals his familiarity with works by T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, Saul Bellow, Herbert Gold, Philip Roth and Norman Mailer. Other contemporary American authors whose fiction is often categorised alongside Pynchon's include John Hawkes, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, Donald Barthelme, John Barth, William Gaddis and Don DeLillo.

Investigations and digressions into the realms of human sexuality, psychology, sociology, mathematics, science and technology recur throughout Pynchon's works. One of his earliest short stories, "Low-lands" (1960), features a meditation on Heisenberg's uncertainty principle as a metaphor for telling stories about one's own experiences. His next published work, "Entropy" (1960), introduced the concept which was to become synonymous with Pynchon's name (though Pynchon later admitted the "shallowness of [his] understanding" of the subject, and noted that choosing an abstract concept first and trying to construct a narrative around it was "a lousy way to go about writing a story"). Another early story, "Under the Rose" (1961), includes amongst its cast of characters a cyborg set anachronistically in Victorian era Egypt (a type of writing now called steampunk). This story, significantly reworked by Pynchon, appears as Chapter 3 of V. "The Secret Integration" (1964), Pynchon's last published story, is a sensitively-handled coming-of-age tale in which a group of young boys face the consequences of the American policy of racial integration. At one point in the story, the boys attempt to understand the new policy by way of the mathematical operation, the only sense of the word with which they are familiar.

The Crying of Lot 49 also alludes to entropy and communication theory, and contains scenes and descriptions which parody or appropriate calculus, Zeno's paradoxes, and the thought experiment known as Maxwell's demon. At the same time, the novel also investigates homosexuality, celibacy and both medically-sanctioned and illicit psychedelic drug use. Gravity's Rainbow describes many varieties of sexual fetishism (including sado-masochism, coprophilia and a borderline case of tentacle rape), and features numerous episodes of drug use, most notably marijuana but also cocaine, naturally-occurring hallucinogens, and the mushroom Amanita muscaria. Gravity's Rainbow also derives much from Pynchon's background in mathematics: at one point, the geometry of garter belts is compared with that of cathedral spires, both described as mathematical singularities. His most recent novel, Mason & Dixon, explores the scientific, theological and sociocultural foundations of the Age of Reason whilst also depicting the relationships between actual historical figures and fictional characters in intricate detail and, like Gravity's Rainbow, is an archetypal example of the genre of historiographical metafiction.

Pynchon's work has been cited as an influence and inspiration by many writers, musicians, artists and filmmakers, including T. Coraghessan Boyle, Don DeLillo, William Gibson, Elfriede Jelinek, Rick Moody, Richard Powers, Salman Rushdie, Neal Stephenson, Laurie Anderson, Zak Smith and Adam Rapp. Thanks to his influence on Gibson and Stephenson in particular, Pynchon became one of the progenitors of cyberpunk fiction. Though the term "cyberpunk" did not become prevalent until the early 1980s, many readers retroactively include Gravity's Rainbow in the genre, along with other works—e.g., Samuel R. Delany's Nova and many works of Philip K. Dick—which seem after the fact to anticipate cyberpunk styles and themes. The encyclopedic nature of Pynchon's novels also led to some attempts to link his work with the short-lived hypertext fiction movement of the 1990s (Page 2002; Krämer 2005).

Gravity's Rainbow and the more recent Mason & Dixon both feature wildly eccentric characters, episodes of frenzied action and frequent digressions on topics which are seemingly tangential to the central narrative. These characteristics, combined with the novels' imposing lengths, have led critic James Wood to classify Pynchon's work as hysterical realism. Other writers whose work has been labelled as hysterical realism include Rushdie, Stephenson and Zadie Smith.

Media scrutiny

Relatively little is known about Thomas Pynchon as a private person; he has carefully avoided contact with journalists for over forty years. Only a few photos of him are known to exist, nearly all from his high school and college days, and his whereabouts have often remained undisclosed.

A review of V. in the New York Times Book Review described Pynchon as "a recluse" living in Mexico, and introduced the media brand name which has pursued Pynchon throughout his career (Plimpton 1963:5). Nonetheless, Pynchon's absence from the public spotlight is one of the notable features of his life, and it has generated many rumors and apocryphal anecdotes.

1970s and 1980s

After the publication and success of Gravity's Rainbow, interest mounted in finding out more about the identity of the author. At the 1974 National Book Award ceremony, the president of Viking Press, Tom Guinzberg, arranged for double-talking comedian "Professor" Irwin Corey to accept the prize on Pynchon's behalf (Royster 2005). Many of the assembled guests had no idea who Corey was, and, having never seen the author, they assumed that it was Pynchon himself on the stage delivering Corey's trademark torrent of rambling, pseudo-scholarly verbiage (Corey 1974). Towards the end of Corey's address a streaker ran through the hall, adding further to the confusion.

An article published in the Soho Weekly News claimed that Pynchon was in fact J. D. Salinger (Batchelor 1976). Pynchon's written response to this theory (reported in Tanner 1982) was simple: "Not bad. Keep trying."

One of the first pieces to cash in on Pynchon's burgeoning repute and notoriety after Gravity's Rainbow was a biographical account written by a former Cornell University friend, Jules Siegel, and printed in Playboy magazine. In the article Siegel reveals that Pynchon had a complex about his teeth (so far as to have undergone oral surgery), was nicknamed "Tom" at Cornell and attended Mass diligently, acted as best man at Siegel's wedding, and that he later also had an affair with Siegel's wife. Siegel recalls Pynchon saying he did attend some of Vladimir Nabokov's lectures at Cornell but that he could hardly make out what Nabokov was saying because of his thick Russian accent. Siegel also records Pynchon's comment that "[e]very weirdo in the world is on my wavelength", an observation borne out by the crankiness and zealotry which has attached itself to his name and work in subsequent years, particularly across the Internet (Siegel 1977).

1990s and 2000s

Pynchon's avoidance of publicity and public appearances caused journalists to continue to speculate about his identity and activities, and reinforced his reputation within the media as "reclusive". More astute readers and critics recognized that there were and are perhaps aesthetic (and ideological) motivations behind his choice to remain aloof from public life. For example, the protagonist in Janette Turner Hospital's short story, "For Mr. Voss or Occupant" (publ. 1991), explains to her daughter that she is writing "a study of authors who become reclusive. Patrick White, Emily Dickinson, J. D. Salinger, Thomas Pynchon. The way they create solitary characters and personae and then disappear into their fictions." (Hospital 1995:361-2) More recently, book critic Arthur Salm has written that "the man simply chooses not to be a public figure, an attitude that resonates on a frequency so out of phase with that of the prevailing culture that if Pynchon and Paris Hilton were ever to meet—the circumstances, I admit, are beyond imagining—the resulting matter/antimatter explosion would vaporize everything from here to Tau Ceti IV" (Salm 2004).

Belying this reputation somewhat, Pynchon has published a number of articles and reviews in the mainstream American media, including words of support for Salman Rushdie and his then wife, Marianne Wiggins, after the fatwa was pronounced against Rushdie by the Iranian ayatollah (Pynchon 1989:29). In the following year, Rushdie's enthusiastic review of Pynchon's Vineland prompted Pynchon to send him another message hinting that if Rushdie were ever in New York, the two should arrange a meeting. Eventually the two did meet, and Rushdie found himself surprised by how much Pynchon resembled the mental image Rushdie had formed beforehand (Hitchens 1997).

In the early 1990s Pynchon married his literary agent, Melanie Jackson, and fathered a son, Jackson, in 1991. The disclosure of Pynchon's location in New York, after many years in which he was believed to be dividing his time between Mexico and northern California, led some journalists and photographers to try to track him down. Shortly before the publication of Mason & Dixon in 1997, a CNN camera crew filmed him in Manhattan. Angered by this invasion of his privacy, he rang CNN asking that he not be identified in the footage of the street scenes near his home. When asked about his reclusive nature he remarked, "My belief is that 'recluse' is a code word generated by journalists ... meaning, 'doesn't like to talk to reporters.'" CNN also quoted him as saying, "Let me be unambiguous. I prefer not to be photographed" (CNN 1997). The next year, a reporter for Sunday Times managed to snap a photo of him as he was walking with his son (Bone 1998).

Pynchon's attempt to maintain his personal privacy and have his work speak for itself has resulted in a number of outlandish rumors and hoaxes over the years. Indeed, claims that Pynchon was the Unabomber or a sympathizer with the Waco Branch Davidians after the 1993 siege were upstaged in the mid-1990s by the invention of an elaborate rumor insinuating that Pynchon and one "Wanda Tinasky" were the same person. A spate of letters authored under that name had appeared in the late 1980s in the Anderson Valley Advertiser in Anderson Valley, California. The style and content of those letters were said to resemble Pynchon's, and Pynchon's Vineland, published in 1990, also takes place in northern California, so it was suggested that Pynchon may have been in the area at that time, conducting research. A collection of the Tinasky letters was eventually published as a paperback book in 1996; however, Pynchon himself denied having written the letters, and no direct attribution of the letters to Pynchon was ever made. "Literary detective" Donald Foster subsequently showed that the Letters were in fact written by an obscure Beat writer called Tom Hawkins, who had murdered his wife and then committed suicide in 1988. Foster's evidence was conclusive, including finding the typewriter on which the "Tinasky" letters had been written (Foster 2000).

An article purporting to be the transcript of an interview with Pynchon in the wake of the September 11 attacks on the U.S. appeared in the December 2001 issue of Playboy Japan. Melanie Jackson, the author's wife and literary agent, subsequently denied the authenticity of this interview.

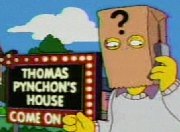

Responding ironically to the image which has been manufactured in the media over the years, during 2004 Pynchon made two cameo appearances on the animated television series The Simpsons. The first occurs in the episode "Diatribe of a Mad Housewife", in which Marge Simpson becomes a novelist. He plays himself, with a paper bag over his head, and provides a blurb for the back cover of Marge's book, speaking in a broad Long Island accent: "Here's your quote: Thomas Pynchon loved this book, almost as much as he loves cameras!" He then starts yelling at passing cars: "Hey, over here, have your picture taken with a reclusive author! Today only, we'll throw in a free autograph! But, wait! There's more!" The second appearance occurs in "All's Fair in Oven War," which was the sixteenth-season premiere. In this appearance Pynchon's dialogue consists entirely of puns on his novel titles (e.g., "the frying of latke 49").

Works

- V. (1963), winner of William Faulkner Foundation Award

- The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), winner of Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award

- Gravity's Rainbow (1973), 1974 National Book Award for fiction, judges' unanimous selection for Pulitzer Prize overruled by advisory board, awarded William Dean Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1975 (award declined)

- Slow Learner (1984), collection of early short stories

- Vineland (1990)

- Mason & Dixon (1997)

As well as fictional works, Pynchon has written essays, introductions and reviews addressing subjects as diverse as missile security, the Watts Riots, Luddism and the work of Donald Barthelme. Some of his non-fiction pieces have appeared in the New York Times Book Review and The New York Review of Books, and he has contributed blurbs for books and records. His 1984 Introduction to the Slow Learner collection of early stories is significant for its autobiographical candour. More recently, he wrote the Introduction to the Penguin Centenary Edition of George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 2003.

References

- Batchelor, J.C. "Thomas Pynchon is not Thomas Pynchon, or, This is End of the Plot Which Has No Name". Soho Weekly News, 22 April 1976. (back)

- Bone, James. "Who the hell is he?" Sunday Times (South Africa), 7 June 1998. (back)

- CNN. "Where's Thomas Pynchon?" 5 June 1997. (back)

- CNN Book News. "Early Nobel announcement prompts speculation". 29 September 1999. (back)

- Corey, Irwin. "Transcript of National Book Award acceptance speech", delivered 18 April 1974. (back)

- Ervin, Andrew. "Nobel Oblige". Philadelphia City Paper 14–21 September 2000. (back)

- Foster, Don. Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous. Henry Holt, New York, 2000. (back)

- Fowler, Douglas. A Reader's Guide to Gravity's Rainbow. Ardis Press, 1980. (back)

- Frost, Garrison. "Thomas Pynchon and the South Bay". The Aesthetic, 2003. (back)

- Grimes, William. "Toni Morrison Is '93 Winner Of Nobel Prize in Literature". New York Times Book Review, 8 October 1993. (back)

- Hitchens, Christopher. "Salman Rushdie: Even this colossal threat did not work. Life goes on." The Progressive, October 1997. (back)

- Hospital, Janette Turner. Collected Stories 1970-1995. University of Queensland Press, 1995. (back)

- Kihss, Peter. "Pulitzer Jurors; His Third Novel". The New York Times, 8 May 1974, p. 38. (back)

- Krämer, Oliver. "Interview mit John M. Krafft, Herausgeber der 'Pynchon Notes'". Sic et Non.

- Page, Adrian. "Towards a poetics of hypertext fiction". In The Question of Literature: The Place on the Literary in Contemporary Theory, edited by Elizabeth B Bissell. Manchester University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-71905-744-2.

- Plimpton, George. "Mata Hari with a Clockwork Eye, Alligators in the Sewer". Rev. of V. New York Times Book Review, 21 April, 1963, p. 5. (back)

- Pynchon, Thomas. "A Journey into the Mind of Watts". New York Times Magazine, 12 June 1966, pp. 34-35, 78, 80-82, 84. (back)

- Pynchon, Thomas. "Words for Salman Rushdie". New York Times Book Review, 12 March 1989. (back)

- Roeder, Bill. "After the Rainbow". Newsweek 92, 7 August 1978. (back)

- Royster, Paul. "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology". Faculty Publications, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2005. (back)

- Salm, Arthur. "A screaming comes across the sky (but not a photo)". San Diego Union-Tribune, 8 February 2004. (back)

- Siegel, Jules. "Who is Thomas Pynchon, and why did he take off with my wife?" Playboy, March 1977. (back)

- Tanner, Tony. Thomas Pynchon. Methuen & Co., 1982. (back)

- Ulin, David. "Gravity's End". Salon, 25 April 1997. (back)

- Weisenburger, Steven C. A Gravity's Rainbow Companion: Sources and Contexts for Pynchon's Novel. University of Georgia Press, 1988. (back)

- Wisnicki, Adrian. "A Trove of New Works by Thomas Pynchon? Bomarc Service News Rediscovered." Pynchon Notes 46-49 (2000-1), pp. 9-34. (back)

External links

- The following links were last verified on 8 February, 2006.

- Literary Encyclopedia biography

- "Look! Up in the Sky! It's a Bird! It's a Plane! It's . . . Rocketman!": Pynchon's Comic Book Mythology in Gravity's Rainbow

- HyperArts Pynchon Pages

- Template:De icon Pynchon Index

- Pynchon Notes, a journal operated by Miami University in Oxford, Ohio

- Protective Coating: Bearing the Weight of Pynchon Using the Spectrum of Freud's Insight An analysis of Pynchon's use of parody in relation to Freudian theory

- The Pynchon-L mailing list

- pynchonoid, a blog which "juxtaposes contemporary texts" with Pynchonian passages

- San Narciso Pynchon Page, hosted in Claremont, California, "a town that looks a lot, in fact, like San Narciso"

- Spermatikos Logos

- Lineland: Mortality and Mercy on the Internet's Pynchon-L@Waste.Org Discussion List by Jules Siegel