Sahajanand Saraswati and Othello: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses}} |

|||

'''Swami Sahajanand Saraswati''' (1889-1950), was born in a Jijhoutia [[Bhumihar| Bhumihar Brahmin]]<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| first = Sharma |

|||

| last = Raghav Sharan |

|||

| title = Builders of Modern India: Swami Sahajanand Saraswati |

|||

| publisher = Prakashan Vibhag, Suchna evam Prasaran Mantralaya, Bharat Sarkar |

|||

| location = New Delhi |

|||

| year = 2001 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

family of [[Gazipur]] of [[Uttar Pradesh]] [[States and territories of India|state]] of [[India]], was an [[ascetic]] ([[Dandi sanyasi]]) of Dashnami Order of [[Adi Shankara]] Sampradaya (a monastic post which only [[Brahmins]] can hold) as well as a [[nationalist]] and peasant leader of [[India]]. Although he was born in [[Uttar Pradesh]] (U.P.), his social and political activities centered mostly in [[Bihar]]. He had set-up an ashram at [[Bihta]],near [[Patna]] and carried out most of his work in the later part of his life from there. |

|||

{{Infobox Play |

|||

[[Government of India]] had issued a commemorative stamp <ref>[http://pib.nic.in/archieve/phtgalry/pgyr2000/pg062000/pg26june2000/260620001.html Shri [[Ram Vilas Paswan]] to release commemorative postage stamp on Swami Sahajanand Saraswati]</ref>in the memory of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, and the stamp was officially released on [[26 June]] [[2000]] by [[Ram Vilas Paswan]], the-then Minister of Communications, Government of India. |

|||

| name = Othello, The Moor of Venice |

|||

| image = FirstFolioOthello.jpg|200px |

|||

| caption = Title page facsimile from the ''[[First Folio]]'', (1623) |

|||

| writer = [[William Shakespeare]] |

|||

| genre = Tragedy |

|||

| setting = Venice and Cyprus |

|||

| subject = |

|||

| premiere = 1 November 1604 |

|||

| place = [[Whitehall Palace]], [[London, England]] |

|||

| orig_lang = {{English}} |

|||

| ibdb_id = |

|||

| iobdb_id = |

|||

}} |

|||

'''''Othello, The Moor of Venice''''' is a tragedy by [[William Shakespeare]] based on the short story "Moor of Venice" by [[Cinthio]], believed to have been written in approximately [[1603]]. The work revolves around four central characters: [[Othello (character)|Othello]], his wife [[Desdemona (Othello)|Desdemona]], his [[lieutenant]] [[Michael Cassio|Cassio]], and his trusted advisor [[Iago]]. Attesting to its enduring popularity, the play appeared in 7 editions between 1622 and 1705. Because of its varied themes — [[racism]], [[love]], [[jealousy]] and [[betrayal]] — it remains relevant to the present day and is often performed in professional and community theatres alike. The play has also been the basis for numerous operatic, film and literary adaptations. |

|||

The [[Indian Council of Agricultural Research]] has an award [[Swamy Sahajanand Saraswati Extension Scientist/ Worker Award]]<ref>http://www.icar.org.in/merits.html</ref> instituted in his honour.<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.icar.org.in/awards.htm |

|||

==Source== |

|||

| title = [[Indian Council of Agricultural Research]] Awards |

|||

The plot for ''Othello'' was developed from a story in [[Giovanni Battista Giraldi|Cinthio]]'s the ''Hecatommithi'', "Un Capitano Moro", which it follows closely. The only named character in Cinthio's story is "Disdemona"<!--this is the correct spelling for Cinthio's version-->, which means "unfortunate" in Greek; the other characters are identified only as "the standard-bearer", "the captain", and "the [[Moors|Moor]]". In the original, the standard-bearer lusts after Disdemona and is spurred to revenge when she rejects him. |

|||

| publisher = [[Indian Council of Agricultural Research]] |

|||

Unlike Othello, the Moor in Cinthio's story never repents the murder of his beloved, and both he and the standard-bearer escape Venice and are killed much later. Cinthio also drew a moral (which he placed in the mouth of the lady) that European women are unwise to marry the temperamental males of other nations.<ref>[http://www.virgil.org/dswo/courses/shakespeare-survey/cinthio.pdf Hecatommithi]</ref> |

|||

| date = 2008-09-03 |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-09-03 |

|||

}}</ref> Bihar Governor [[R. S. Gavai]] released a book on the life of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati on his 57th death anniversary in Patna.<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.patnadaily.com/news2007/june/062607/tribute_to_sahajanand.html |

|||

| title = Governor Pays Rich Tribute to Swami Sahajanand |

|||

| publisher = PatnaDaily.com |

|||

| date = 2007-06-26 |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-08-19 |

|||

}}</ref> Chief Minister [[Nitish Kumar]], along with other Bihar leaders celebrated the 119th birth anniversary of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, the architect of the farmers' movement.<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.patnadaily.com/news2008/mar/030508/sahajanand_birth_anniversary.html |

|||

| title = Swami Sahajanand Saraswati's Birth Anniversary Observed |

|||

| publisher = PatnaDaily.com |

|||

| date = 2008-03-05 |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-08-19 |

|||

}}</ref> Present [[Minister of Railways]], president of [[Rashtriya Janata Dal]] and former [[Chief Minister of Bihar]], [[Laloo Prasad Yadav]] had promised way back in 2003 to erect a life-size atatue of Swamiji at [[Patna]] exhorting that the “The [[BJP]] should have installed his portrait in [[Parliament]]".<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| url = http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/cms.dll/html/uncomp/articleshow?artid=39106910 |

|||

| title = Forget past, Laloo tells Bhumihars at rally |

|||

| publisher = [[Times of India]] |

|||

| date = 2003-03-03 |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-08-30 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[Othello (character)|Othello's character]], in particular, is believed to have been inspired by several Moorish [[delegation]]s from [[Morocco]] to [[Elizabethan England]] at the beginning of the 17th century.<ref name=Matar>Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), ''Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor'', [[Sam Wanamaker]] Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare’s [[Globe Theatre]] ([[cf.]] [[Mayor of London]] (2006), [http://www.london.gov.uk/gla/publications/equalities/muslims-in-london.pdf Muslims in London], pp. 14-15, Greater London Authority)</ref> |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

The foremost of the leaders of the peasantry in [[Bihar]] was Swami Sahajanand Saraswati. Sahajanand was born in [[Ghazipur]] district in eastern U.P. in the late nineteenth century (1889?) [Sahajanand, 1952] to a family of [[Bhumihar| Bhumihar Brahmin]] of Jujautia clan. He was the last of six sons and had no sisters. His mother died when he was a child and Naurang Rai (as he was known then) was raised by an aunt. His father, Beni Rai was primarily a cultivator, and was so divorced from priestly functions that he did not even know the gayatri mantras. The family held a small zamindari, income from which had sufficed in Sahajanand's grandfathers' time, but as the family grew and the land was partitioned, prosperity dwindled and (tenant) cultivation became the main occupation. However, the family was not so extremely poor that its condition would prevent Naurang from going to school, where he did very well both in the primary grades and in the German Mission high school where he studied English. Even at an early age, however, Naurang showed sings of brilliance and scepticism of conventional populist religious practices. He questioned the institution of people taking guru- mantra from fake religious personages and wanted to study religious texts deeply in order to be able to find real spiritual solace by renouncing the world. To prevent him from doing this, his family had him married to a child bride but, before the marriage could stablise, in 1905 or early 1906, his wife died. The last fetter in his way to sanyas (renunciation of the world) having been removed, in 1907 Naurang Rai was initiated into holy orders and took on the name of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati. This adoption of sanyas prevented him from appearing for the matriculation examination but he spent the rest of his life, especially the first seven years after sanyas, in studying religion, politics and social affairs. In all these he became increasingly radicalised so that towards the end of his life, the world was presented with the incongruous sight of a saffron-clad swami who denounced organised religion [Sahajanand, 1948:96-123]. |

|||

==Date and text== |

|||

==Metamorphosis from narrow to national interests== |

|||

[[Image:Othello title page.jpg|thumb|right|Title page of the first [[quarto]] edition of ''Othello'', published in 1622]] |

|||

However, before Sahajanand came to this stage, he had to traverse a long road. Quite naturally, his first involvement in public activity started from the narrow [[Bhumihar| Bhumihar Brahmin]] platform. Only gradually did Sahajanand become involved in nationalist [[Congress]] politics, and then in [[peasant movements]], progressively in [[Patna]], [[Bihar]] and, finally, all over [[India]]. |

|||

The play was entered into the [[Stationers' Register|Register]] of the [[Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers|Stationers Company]] on [[October 6]], [[1621]] by [[Thomas Walkley]], and was first published in [[book size|quarto]] format by him in 1622, printed by [[Nicholas Okes]], under the title ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice''. Its appearance in the [[First Folio]] (1623) quickly followed. Later quartos followed in 1630, 1655, 1681, 1695, 1699 and 1705; on stage and in print, it was a popular play. |

|||

==Characters== |

|||

Even in order to get to the peasant question, however, Sahajanand went through political schooling in the [[Indian National Congress]] under [[Gandhi]]. In fact, the Swami and the Mahatma had a curious filial relationship. Sahajanand started off in Congress as a devoted Gandhian, admiring Gandhi's fusion of tradition, religion and politics and, by 1920, threw himself into the nationalist movement as directed by Gandhi. However, he first became disgusted with the petty, comfort-seeking hypocrisy of the self-proclaimed `Gandhians' especially in jail and, within 15 years, he was disillusioned with Gandhi's own ambiguity and devious pro-propertied attitudes. The final break came in 1934 after Bihar had been violently shaken by the great earthquake of that year. During the relief operations in which Sahajanand was deeply involved, he came across many cases where, in spite of the destruction perpetrated by the natural calamity, he found the suffering of the people to be less on account of the earthquake than as the result of the cruelty of the landlords in rent collection. When Sahajanand found no way of tackling this situation, he went to meet Gandhi, who was then camping at Patna, to ask for advice. Gandhi sanguinely told him, 'the zamindars will remove the difficulties of the peasants. Their managers are Congressmen. So they will definitely help the poor' [Sahajanand, 1952:426]. In spite of this, the oppression of the peasantry by the `zamindari machinery including Congressmen managers' continued. These platitudes of Gandhi disgusted Sahajanand and he broke off his 14 year association with the Mahatma. After that, he consistently saw the Mahatma as a wily politician who, in order to defend the propertied classes, took recourse in pseudo-spiritualism, professions of non-violence and religious hocus-pocus. |

|||

*'''[[Othello (character)|Othello]]''', a [[Moors|Moor]] in the service of the [[Republic of Venice]] and Desdemona's husband |

|||

*'''[[Desdemona (Othello)|Desdemona]]''', Othello's wife and Brabantio's daughter |

|||

*'''[[Iago]]''', Othello's ensign (standard bearer) |

|||

*'''[[Emilia (Othello)|Emilia]]''', Iago's wife and Desdemona's maid |

|||

*'''[[Michael Cassio|Cassio]]''', Othello's lieutenant |

|||

*'''[[Bianca (Othello)|Bianca]]''', a courtesan involved with Cassio |

|||

*'''[[Brabantio]]''', a Venetian senator and Desdemona's father |

|||

*'''Roderigo''', a Venetian who harbours an unrequited love for Desdemona |

|||

*'''[[Doge of Venice|Duke of Venice]]''', or the "Doge" |

|||

*'''Gratiano''', Brabantio's brother |

|||

*'''Lodovico''', Brabantio's kinsman and Desdemona's cousin |

|||

*'''Montano''', Othello's Venetian predecessor in the government of Cyprus |

|||

*'''Clown''', Montano's servant |

|||

*Officers, Gentlemen, Messenger, Musicians, Herald, Sailor, Attendants, servants etc. |

|||

==Synopsis== |

|||

After his break with Gandhi, Sahajanand kept out of party politics (though he continued to be a member of the Congress) and turned his energies into mobilising the peasants [Hauser, 1961:109-133]. By the end of the decade, he emerged as the foremost kisan leader in India. In this task of organising the peasants, at different times his political impetuosity took him close to different individuals, parties and groups. He first joined hands with the Congress Socialists for the formation of the [[All India Kisan Sabha]]; then with [[Subhas Chandra Bose]] organised the Anti-Compromise Conference against the [[United Kingdom|British]] and the [[Congress]] [Sahajanand, 1940]; then worked with the [[Communist Party of India]] during the [[Second World War]] [Das, 1981]; and finally broke from them, too, to form an `independent' Kisan Sabha [Rai, 1946]. In spite of these political forays, however, Sahajanand remained essentially a non-party man and his loyalty was only to the peasants for whom he was the most articulate spokesman and forthright leader. As a peasant leader, `by standards of speech and action, he was unsurpassed' [Hauser, 1961:85]. He achieved that status by a remarkable ability to speak to and for the peasants of Bihar; he could communicate with them and articulate their feelings in terms whose meaning neither peasant nor politicians could mistake. `He was relentlessly determined to improve the peasants' condition and pursued that objective with such force and energy that he was almost universally loved by the peasants, and almost equally both respect and feared by the landlords, Congressmen and officials. The Swami was a militant agitator; he sought to expose the condition of agrarian society and to organise the peasants massively to achieve change. He did this through countless meetings and rallies which he organised and which he addressed in his own inimitable forthright manner. He was a powerful speaker speaking the language of the peasants. Sahajanand was a Dandi Sanyasi and always carried a long bamboo staff (danda). In the course of the movement, this staff became the symbol of peasant resistance. They cry of "Danda Mera Zindabad" (Long live my staff), was thus taken to mean "Long live the danda (lathi) of the Kisans" and it became the watchword of the Bihar peasant movement. The inevitable response by the masses of peasants was "Swamiji ki Jai" (Victory to Swamiji) [Hauser, op cit]. "Kaise Logey Malguzari, Latth Hamara Zindabad" (How will you collect rent as long as our sticks are powerful?) became the battle cry of the peasants. |

|||

[[Image:Othello-cwcope-1853.jpg|thumb|left|220px|Othello relating his adventures to Desdemona, (steel engraving by [[Charles Knight]], 1873)]] |

|||

The play opens with Roderigo, a rich and foolish gentleman, complaining to Iago, a high-ranking soldier, that Iago has not told him about the secret marriage between [[Desdemona (Othello)|Desdemona]], the daughter of a Senator named Brabantio, and Othello, a black general of the Venetian army. He is upset by this development because he loves Desdemona and has previously asked her father for her hand in marriage. Iago is upset with Othello for promoting a younger man named Michael Cassio above him, and tells Roderigo that he (Iago) is simply using Othello for his own advantage. Iago's argument against Cassio is that he is a scholarly tactician and has no real battle experience from which he can draw strategy. By emphasizing this point, and his dissatisfaction with serving under Othello, Iago convinces Roderigo to wake Brabantio and tell him about his daughter's marriage. After Roderigo rouses Brabantio, Iago says aside that he has heard rumors that Othello has had an affair with his wife, [[Emilia (Othello)|Emilia]]. This acts as the second explicit motive for Iago's actions. Later, Iago tells Othello that he overheard Roderigo telling Brabantio about the marriage and that he (Iago) was angry because the development was meant to be secret. This is the first time in the play that we see Iago blatantly lying. |

|||

This was the manner in which a common communication was achieved. And it was vastly enhanced by the fact that Sahajanand was a Swami, which gave him a tremendous charisma. In 1937, he was reported to have said that as religious robes had long exploited the peasants, now he would exploit those robes on behalf of the peasants' [Hauser, ibid]. When landlords raised the question as to how a sanyasi (mendicant) was taking part in temporal problems of the poor, Sahajanand quoted the scriptures at them: |

|||

News arrives in the Senate that the Turks are going to attack Cyprus; therefore Othello is summoned to advise. Brabantio arrives and accuses Othello of seducing Desdemona by [[witchcraft]], but Othello defends himself successfully before an assembled Senate, explaining that Desdemona became enamored of him for the stories he told of his early life. |

|||

Prayen deva munayah swavimukti kama |

|||

By order of the Duke, Othello leaves [[Venice]] to command the Venetian armies against invading Turks on the island of [[Cyprus]], accompanied by his new wife, his new lieutenant Cassio, his [[Ensign (rank)|ensign]] [[Iago]], and Iago's wife [[Emilia (Othello)|Emilia]], who works as a maid to Desdemona. When they arrive, they find that a storm has destroyed the Turkish fleet, and all break out in celebration. |

|||

Maunam charanti vijane na pararthnsihthah |

|||

[[Iago]], who resents Othello for favoring Cassio, takes the opportunity of Othello's absence from home to manipulate his superiors and make Othello think that his wife has been unfaithful. He persuades Roderigo to engage Cassio in a fight, then gets Cassio drunk. When Othello discovers Cassio drunk and in a fight, he strips him of his rank and confers it upon Iago, which in turn strips Iago of one of his two stated reasons to exact revenge on Othello. After Cassio sobers, Iago persuades Cassio to have Desdemona act as an intermediary between himself and Othello, hoping that she will persuade the Moor to reinstate Cassio. It is of some note that throughout the text, Othello and other characters refer to Iago as "good" and "honest". |

|||

Naitan vihaya kripnan vimumuksha eko |

|||

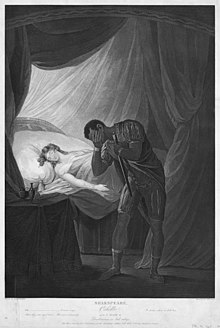

[[Image:Josiah Boydell Desdemona in bed asleep - Othello Act V scene 2.jpg|thumb|left|220px|"Desdemona in bed asleep", from Othello (Act V, scene 2), part of "A Collection of Prints, from Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakspeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain", published by John and Josiah Boydell (1803)]] |

|||

Nanyattwadasya sharanam bhramato nupashye |

|||

Iago now persuades Othello to be suspicious of Desdemona and Cassio. As it happens, Cassio is courting a woman named Bianca, who is a seamstress and prostitute. Desdemona drops a handkerchief that was Othello's first gift to her and which he has stated holds great significance to him in the context of their relationship; Emilia obtains this for Iago, who has asked her to steal it, having decided to plant it in Cassio's lodgings as evidence of Cassio and Desdemona's affair. Emilia is unaware of what Iago plans to do with the handkerchief. After he has planted the handkerchief, Iago tells Othello to stand apart and watch Cassio's reactions while Iago questions him about the handkerchief. He goads Cassio on to talk about his affair with Bianca; because Othello cannot hear what they are saying, Othello thinks that Cassio is referring to Desdemona. Bianca, on discovering the handkerchief, chastises Cassio. Enraged and hurt, Othello decides to kill his wife and orders Iago to kill Cassio. |

|||

(Mendicants are selfish, living away from society, they try for their own salvation without caring for others. I cannot do that, I do not want my own salvation apart from that of the many destitutes. I will stay with them, live with them and die with them)[Sahajanand, 1952:171]. |

|||

Iago convinces Roderigo to kill Cassio because Cassio has just been appointed in Othello's place, whereas if Cassio lives to take office, Othello and Desdemona will leave Cyprus, thwarting Roderigo's plans to win Desdemona. Roderigo attacks Cassio in the street after Cassio leaves Bianca's lodgings and they fight. Both are wounded. Passers-by arrive to help; Iago joins them, pretending to help Cassio. Iago secretly stabs Roderigo to stop him talking and accuses Bianca of conspiracy to kill Cassio. |

|||

Such was Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, the charismatic sanyasi rebel, who laid the foundations of kisan organisation in [[Bihar]], built it up into a massive movement, spread it to other parts of [[India]] and radicalised it to such an extent that what had started off as a move to bring about reform in the zamindari system, ended up by destroying the system itself. Sahajanand could not, however, witness the legal death of [[zamindari]] in [[Bihar]]. While the battle for this was still being fought in the legislature and the courts, on 26 June 1950, Sahajanand died [Sudhakar, 1973:14]. |

|||

In the night, Othello confronts Desdemona, and then kills her by [[Asphyxia|smothering]] her in bed, before Iago's wife, Emilia, arrives. At Emilia's distress, Othello tries to explain himself, justifying his actions by accusing Desdemona of adultery. Emilia calls for help. The Governor arrives, with Iago and others, and Emilia begins to explain the situation. When Othello mentions the handkerchief (distinctively embroidered) as proof, Emilia realizes what Iago has done; she exposes him, whereupon Iago kills her. Othello, realizing Desdemona's innocence, attacks Iago but does not kill him, saying that he would rather have Iago live the rest of his life in pain. Lodovico, a Venetian nobleman, apprehends both Iago and Othello, but Othello commits [[suicide]] with a dagger, holding his wife's body in his arms, before they can take him into custody. At the end, it can be assumed, Iago is taken off to be [[torture]]d and possibly [[capital punishment|executed]]. |

|||

==The Organisation== |

|||

==Themes and tropes== |

|||

Swami Sahajanand Saraswati was, of course, a fascinating personality but what also added immense social significance to him was the fact that he was able to found a massive organisation. This took a great deal of both imagination and effort and the fact that it has had a turbulent history is evidence of the role of the individual as well as the relevance of the political-economic context. |

|||

{{SectOR|date=October 2007}} |

|||

===Othello's racial classification=== |

|||

Although the [[Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha]] was formed in 1929 and a smaller [[Kisan Sabha]] had been formed even earlier in [[Patna district]] with a formal organisational structure, it really was institutionalised only after a few years. Actually, it is correct to say that the Kisan Sabha never really became an `organisation', but remained a movement [Hauser, 1961:87]. |

|||

[[Image:MoorishAmbassador to Elizabeth I.jpg|thumb|Portrait of Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Moorish Ambassador to Queen Elizabeth]] |

|||

There is no consensus over [[Othello (character)|Othello]]'s [[Race (classification of human beings)|racial classification]]. Othello is referred to as a "[[Moors (meaning)|Moor]]", but for Elizabethan English people, this term could refer either to the [[Berber people|Berbers]] or [[Arab]]s of [[North Africa]], to the people now called "[[Black (people)|black]]", or to [[Muslim]]s in general. In his other plays, Shakespeare had previously depicted what he called a "tawny Moor" (in ''[[The Merchant of Venice]]'') and a black Moor (in ''[[Titus Andronicus]]''). |

|||

E.A.J. Honigmann, the editor of the Arden edition, concludes that Othello's race is ambiguous. Various uses of the word 'black' (for example, "Haply for I am black") are insufficient evidence, Honigmann argues, since 'black' could simply mean 'swarthy' to Elizabethans.<ref>''Oxford English Dictionary'', 'Black', 1c.</ref> Moreover, Iago twice uses the word 'Barbary' or 'Barbarian' to refer to Othello, seemingly referring to the [[Barbary]] coast inhabited by the "tawny" Moors. Roderigo calls Othello 'the thicklips', which seems to refer to European conceptions of Sub-Saharan African physiognomy, but Honigmann counters that, arguing that because these comments are all insults, they need not be taken literally.<ref>E.A.J. Honigmann, ed. ''Othello''. London: Thomas Nelson, 1997, p. 15.</ref> Furthermore, Honigmann notes a piece of external evidence: an ambassador of the Arab King of Barbary with his retinue stayed in London in 1600 for several months and occasioned much discussion. Honigmann wonders whether Shakespeare's play, written only a year or two afterwards, might have been inspired by the ambassador.<ref>Honigmann, 2-3.</ref> |

|||

But if that is so for the whole of the history of the Sabha, in its first years it was even more nebulous: an idea, a forum, a propaganda platform, a lobby. Almost immediately after the formation of the Sabha Bihar was plunged, with the rest of India, into the Civil Disobedience Movement, which, although it helped in arousing the general consciousness of the masses, did not give the leaders of the Sabha the time to formalise its structure [Williams, 1933:1- 30]. In fact, the experiences of the [[Civil Disobedience Movement]] both outside and inside jails created the beginnings of the rift between the Kisan Sabhaites and some of the Congress leaders [BSCRO:21/1933], and so disgusted the supreme leader of the Sabha, Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, that for several years he cut himself off from politics altogether [Sahajanand, 1952:373-381]. |

|||

Michael Neill, editor of the Oxford Shakespeare edition, disagrees, arguing that the earliest external references to Othello's colour ([[Thomas Rymer]]'s 1693 critique of the play, and the 1709 engraving in [[Nicholas Rowe (dramatist)|Nicholas Rowe]]'s edition of Shakespeare) assume him to be a black man, while the earliest known North African interpretation was [[Edmund Kean]]'s production of 1814.<ref>Michael Neill, ed. ''Othello'' (Oxford University Press), 2006, p. 45-7.</ref> Modern-day readers and theatre directors now normally lean towards the "black" interpretation, and North African Othellos are rare.<ref>Honigmann, 17.</ref> |

|||

But while, because of these problems, the Kisan Sabha remained disorganised, the landlords recognised its potentially dangerous character. In order to meet its challenge and to consolidate their position, they organised themselves and their supporters into three main bodies. The first was a clearcut Bihar Landholders' Association which included within it all the prominent zamindars. The second was a more clever attempt to hide the organisation's basic class character; it was called the United Party and was supposed to represent the interests of various sections of the population. It even included a few Congressmen though its leadership was composed of the leading landlords, including the Maharajadhiraj of [[Darbhanga]] and the Raja of Surajpura. Having failed in their first attempt in 1928-29 to get the Tenancy Act amended, the landlords tried to do so through this United Party. Rai Bahadur Shyamnandan Sahay, one of the richest zamindars of Bihar, accordingly drew up a new tenancy bill with the obvious intention of strengthening the zamindars' position by giving them more powers. However, in order to achieve a semblance of zamindar-tenant unity in presenting the new legislation, the United Party conspired to develop a compromise measure by forming a `Kisan Sabha' which held its meeting at Patna early in 1933 [Sankrityayana, 1943:112]. Ironically, it was this effort of the landholders which brought Sahajanand back into politics and vastly strengthened the Kisan Sabha [Sudhakar, 1973:9]. |

|||

===Iago / Othello=== |

|||

There was no unanimity among Congressmen about their approach to the United Party and its `Kisan Sabha'. While leaders like [[Rajendra Prasad ]]felt that as an election trick the United Party was doomed to failure, they also thought it might actually gain some concessions for the peasantry. Hence they felt opposition to the United Party was `unnecessary'. Some other Congress leaders thought otherwise: |

|||

Although the title suggests that the tragedy belongs primarily to Othello, Iago is also an important role and has more lines than the title character. In ''Othello'', it is Iago who manipulates all other characters at will, controlling their movements and trapping them in an intricate net of lies. [[A. C. Bradley]] — and more recently [[Harold Bloom]] — have been major advocates of this interpretation.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shakespeare |first=William |authorlink= |coauthors=Ruffiel, Burton |editor= |others=Bloom, Harold |title=Othello (Yale Shakespeare) |origdate=Oct. 3 |origyear=2005 |publisher=Yale University Press}}</ref> |

|||

Other critics, most notably in the later twentieth century (after [[F. R. Leavis]]), have focused on Othello. Apart from the common question of jealousy, some argue that his [[honour]] is his undoing, while others address the hints of instability in his person (in Act IV Scene I, for example, he falls "into a trance").{{Fact|date=May 2008}} |

|||

My colleagues were agitated thinking that (an amended tenancy law) would increase the new party's influence among the peasants. They wanted the move to be opposed, but most of the Congressmen were in prison and the organisation was banned and could not do anything. They thought, therefore, of reviving the dormant Kisan Sabha. Word was passed on to Swami Sahajanand to activise the Kisan Sabha and expose the United Party's move... I felt that all this was unnecessary but, as I could not oppose it, kept quiet. [Prasad, 1957:361]. |

|||

===Sexuality=== |

|||

Sahajanand was apprised of the `bogus Kisan Sabha' and its proposed session at Patna by [[Pandit Yadunandan (Jadunandan) Sharma]] and induced by him to attend the meeting. After much hesitation about re-entering politics, Sahajanand agreed and made a dramatic entry in the Patna meeting which was being conducted by such well-known zamindars and their henchmen as Dr Sachidanand Sinha (the `Founder Modern Bihar') and Guru Sahay Lal (later President of the [[Bihar Chamber of Commerce]]). The Swami's unexpected presence caused considerable embarrassment to the sponsors of the meeting and his forthright stand there condemning such devious manoeuverings marked the end of the effort by the zamindars to play politics through the use of the name of the Kisan Sabha. At the same time, this abortive attempt proved that even the zamindars had recognised the potential of an organisation like the Kisan Sabha even though until then it was no more than a name. Recognising that even the name spelled powerful magic for the Kisans, Sahajanand decided to organise the Sabha. |

|||

At the beginning of the 21st century, several critics inferred that the relationship between the Moor and his Ancient is one of Shakespeare's characteristic subtexts of repressed homosexuality. Most notably [[David Somerton]], [[Linford S. Haines]] and JP Doolan-York in their 2006 publication "Notes for Literature Students on the Tragedy of Othello", devote several chapters to arguing the case for 'Sexuality and Sexual Imagery' in the play. They analyze in great depth the play's climax, Act III Scene III, with its oaths, vows, and formal, semi-ritualistic declarations of love and commitment as being a dark [[parody]] of a [[heterosexual]] [[wedding]] ceremony; they continue by saying that Iago replaces Desdemona in Othello's affections. |

|||

In spite of the efforts of Swami Sahajanand in the direction of giving the Kisan Sabha a live but formal organisational structure, it remained more a movement than an organisation. However, after 1934, the movement was, in a way, institutionalised though its primary instruments of operation continued to by numerous meetings, rallies, `struggles' and annual conventions rather than paper-work. This was a reflection of the impatient leadership of Sahajanand which, in spite of resolutions to the contrary, was not basically concerned with the formal niceties of organisation. While the agitational character marked the movement as necessarily transitory in nature, it also provided it with an element of spontaneous strength. While the Congress relied on its organisational character for mobilising the people for its movements, the Kisan Sabha drew its organisational vitality from the different movements and struggles. And, for the time being at least, the Kisan Sabha's mode of working was more effective. Even the officials remarked that the `Kisan Sabha touches the ryot more directly and its meetings are larger than the Congress' [BSCRO:16/1935]. |

|||

Somerton, Haines, and Doolan-York come to the conclusion that Iago is a pre-[[Jungian]] expression of Shakespeare's [[shadow (psychology)|shadow]], his repressed homosexuality (which remains the subject of much heated debate among today's scholars). This also would explain why the antagonist of this tragedy is so much more appealing and developed as a character than in any of Shakespeare's other plays. The discourse concludes with the speculation that Shakespeare has drawn on the [[androphilia]] of Classical society and that Iago's unrequited love for the General is the explanation for his otherwise motiveless but passionate loathing. |

|||

But Sahajanand also recognised and emphasised the need for organisation of the peasants, except that organisation to him meant organisation of mass action rather than a fossilised hierarchy of constitutional formalities: |

|||

==Critical analysis== |

|||

You must speak in great numbers. Government officials are here and when you come in tens of thousands they will listen, otherwise they will think you need nothing because you are silent. In [[Gaya]] there were 50,000 kisans and it caused a furore... We do not teach you to assault zamindars, only to get what is your right. We do not seek to create trouble between zamindars and tenants. The Government, zamindars and capitalists are strong. I want you to be strong too and the way to do it is to hold meetings. If you do not organise and hold Kisan Sabhas, troubles will not end [BSCRO:16/1935/I)]. |

|||

There have been many differing views on the character of Othello over the years. They span from describing Othello as a hero to describing him as an egotistical fool. A.C Bradley calls Othello the "most romantic of all of Shakespeare's heroes" and "the greatest poet of them all". On the other hand, F.R. Leavis describes Othello as "egotistical". There are those who also take a less critical approach to the character of Othello such as [[William Hazlitt]]. Hazlitt makes a statement that would now be regarded as [[xenophobic]], saying that "the nature of the Moor is noble...but his blood is of the most inflameable kind". |

|||

[[Laurence Olivier]] in his book, ''[[On Acting]]'' offers a comical fiction of how Shakespeare came to write Othello. He imagined [[Richard Burbage]] and Shakespeare getting drunk one night together and, as drunken colleagues are wont to do, both begin bragging about their greatness until finally he imagined Burbage to shout, "I'm the best actor and there's nothing you can write that I can't perform!" |

|||

The formal organisational structure of the movement was expressed through the Rules of 1929 and the Constitution framed in 1936. The 1936 Constitution served as the official statement of organisation form and objectives which included the winning of the `fundamental rights' of the peasants [BPKS, 1936]. It also outlined the rules and procedures for membership and other organisational details. All peasants were admitted as members of the Kisan Sabha with a membership fee reduced from two annas (Rs.0.12) to one price (Rs.0.015) in 1936. The basis of organisation was the village, or gram Kisan Sabha, electing representatives to thana Kisan Sabhas, which similarly elected members to the district body which in turn elected members of the Provincial Kisan Sabha. The executive organ of each of these bodies was the Kisan Council, elected by respective memberships. In the case of the Provincial Kisan Sabha, the Kisan Council comprised 15 members including officer-bearers who were specifically designated as a president, secretary and two joint secretaries. However, in practice there was considerable variation, with an increase in the number of joint secretaries normally to cover regional areas and often there were also some vice-presidents. These offices were all held for an annual term but a treasurer was elected to serve `until it was thought necessary to change him'. Income was derived from membership fees and from small levies on the members of various councils, with funds divided between local and provincial bodies. Provision was made for annual sammelans, or conventions of the several bodies of the Kisan Sabha with a president elected for such conferences. it was indicated that reports of the provincial sammelans were to be printed. |

|||

==Performance history== |

|||

In practice, the formal organisation of the movement was confined to the activities of the Provincial Kisan Council and the annual provincial sammelan, though, on an irregular basis, sammelans at other levels were also held. In addition, a secretary was active for the period of 1935 to 1940 and an office was maintained at the Bihta ashram of Swami Sahajanand. In very large measure, the Swami himself co-ordinated much of the work of the Provincial Kisan Sabha when it was formed. |

|||

[[Image:Stanislavski as Othello 1896.jpg|thumb|right|160px|The seminal [[Russians|Russian]] [[actor]] and [[theatre practitioner]] [[Constantin Stanislavski]] as Othello in 1896.]]''Othello'' possesses an unusually detailed performance record. The first certainly-known performance occurred on November 1, 1604, at [[Whitehall Palace]] in [[London]]. Subsequent performances took place on Monday, [[April 30]], [[1610]] at the [[Globe Theatre]]; on [[November 22]], [[1629]]; and on [[May 6]], [[1635]] at the [[Blackfriars Theatre]]. ''Othello'' was also one of the twenty plays performed by the [[King's Men (playing company)|King's Men]] during the winter of 1612-13, in celebration of the wedding of Princess [[Elizabeth Stuart|Elizabeth]] and [[Frederick V, Elector Palatine]].{{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

The membership of the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha was estimated at 80,000 in 1935 and the figure for 1938 was placed at upwards of 250,000, which made it by far the largest such provincial body in India. However, these and all other membership figures can be taken as no more than approxzimations. Verification is extremely difficult in the absence of any other data as a basis of comparison. The one possible measure of activity and an indication of participation, if not of membership, is to be derived from the press and official estimates of local meetings and provincial rallies. At the height of the agitation, Sahajanand consistently addressed local village meetings of up to 5000 peasants, and the estimates of peasant rallies in Patna were commonly as high as or even higher than 100,000. |

|||

At the start of the [[English Restoration|Restoration]] era, on [[October 11]], [[1660]], [[Samuel Pepys]] saw the play at the [[Cockpit Theatre]]. [[Nicholas Burt]] played the lead, with [[Charles Hart (17th-century actor)|Charles Hart]] as Cassio; [[Walter Clun]] won fame for his Iago. Soon after, on [[December 8]] [[1660]], [[Thomas Killigrew]]'s new [[King's Company]] acted the play at their Vere Street theatre, with [[Margaret Hughes]] as Desdemona—probably the first time a professional actress appeared on a public stage in England. |

|||

With the formation of the [[All India Kisan Sabha]] at [[Lucknow]] in April 1936, the Bihar Kisan Sabha became one of the provincial units of that national body. The [[Congress Socialist Party]] pressed for the organisation of an all-India peasant association, and [[N.G. Ranga]] [1949:69; 1968:216] became a prime mover in the effort. While Sahajanand was named president of the first meeting at Lucknow, he had come to support the idea reluctantly, holding that a national organisation could function effectively only on the basis of a network of well-developed provincial bodies, which did not in fact exist [Sahajanand, 1952:449-453]. While Sahajanand, once involved, extended total support, and to a large extent created and maintained the organisational framework by his own efforts, the A.I.K.S. suffered from the very shortcomings he had indicated: there was insufficient local depth to sustain a national movement [Mitra, 1938:387-389]. |

|||

It may be one index of the play's power that ''Othello'' was one of the very few Shakespearean plays that was never adapted and changed during the Restoration and the eighteenth century.<ref>F. E. Halliday, ''A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964,'' Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 346-47.</ref> Famous nineteenth century Othellos included [[Edmund Kean]], [[Edwin Forrest]], [[Ira Aldridge]], and [[Tommaso Salvini]], and outstanding Iagos were [[Edwin Booth]] and [[Henry Irving]]. |

|||

Some of his ''followers'' and ''students'' in the spirit of serving the deprived masses were [[Pandit Yamuna Karjee]], [[Pandit Karyanand Sharma]], [[Pandit Yadunandan (Jadunandan) Sharma]] and [[Pandit Panchanan Sharma]], [[Rahul Sankrityayan]] and [[Baba Nagarjun]]. |

|||

[[Image:Robeson Hagen Othello.jpg|thumb|left|250px|The 1943 run of ''Othello'' — starring [[Paul Robeson]] and [[Uta Hagen]] — holds the record for the most performances of any Shakespeare play ever produced on [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]].]]The play has maintained its popularity into the 21st century. The most famous American production may be [[Margaret Webster]]'s 1943 staging starring [[Paul Robeson]] as Othello and [[Jose Ferrer]] as Iago. This production was the first ever in the [[United States of America]] to feature a black actor playing Othello with an otherwise all-white cast (there had been all-black productions of the play before). It ran for 296 performances, almost twice as long as any other [[Shakespearean]] play ever produced on [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]]. Although it was never filmed, it was the first nearly complete performance of a Shakespeare play released on records. Robeson had first played the role in [[London]] in 1931 opposite a cast that included [[Peggy Ashcroft]] as Desdemona and [[Ralph Richardson]] as Roderigo, and would return to it in 1959 at [[Stratford on Avon]]. |

|||

Swamiji established an ashram at [[Neyamatpur]], [[Gaya]] ([[Bihar]]) which later became the centre of freedom struggle in bihar. All the prominent leaders of congress visited there frequently to meet [[Pandit Yadunandan (Jadunandan) Sharma]], the leader of Kisaan Aandolan. |

|||

Another famous production was the 1982 [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] staging with [[James Earl Jones]] as Othello and [[Christopher Plummer]] as Iago, who became the only actor to receive a [[Tony Award]] nomination for a performance in the play. |

|||

Few will know that it was [[Yadav]] peasants who, in 1927, pleaded with Sahajanand to aid them in their struggles against the [[Bhumihar| Bhumihar Brahmin]] [[zamindars]] of Masaurhi, and that it was from that beginning that the most powerful peas-ant movement in India, the [[Bihar provincial Kisan Sabha]], emerged.<ref>{{cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.lib.virginia.edu/area-studies/SouthAsia/Misc/Sss/whpsnts96.html |

|||

| title = Peasant Surprise |

|||

| author = Walter Huaser |

|||

| publisher = [[The Telegraph (Kolkata]]), 21 May 1996, p. 8 |

|||

| date = 1996-05-21 |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-04-01 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

And among the many beneficiaries of that movement were precisely those productive and upwardly mobile middle caste groups now courted so assiduously by the [[Janata Dal]], the [[Samata Party]], the [[Congress]], and indeed, the [[BJP]] |

|||

When [[Laurence Olivier]] played his legendary and wildly acclaimed performance of Othello at the [[Royal National Theatre]] in 1964, he had developed a case of stage fright that was so profound that when he was alone onstage, [[Frank Finlay]] (who was playing Iago) would have to stand offstage where Olivier could see him to settle his nerves.<ref>Laurence Olivier, ''Confessions of an Actor'', Simon and Shuster (1982) p. 262</ref> This performance was recorded complete on LP, and filmed by popular demand in 1965 (according to a biography of Olivier, tickets for the stage production were notoriously hard to get). The film version still holds the record for the most [[Academy Award|Oscar]] nominations for acting ever given to a Shakespeare film - Olivier, Finlay, [[Maggie Smith]] (as Desdemona) and [[Joyce Redman]] (as Emilia, Iago's wife) were all nominated for [[Academy Awards]]. Olivier was among the last white actors to be greatly acclaimed as Othello, although the role continued to be played by such performers as [[Paul Scofield]] at the [[Royal National Theatre]] in [[1980]], [[Anthony Hopkins]] in the [[BBC Shakespeare]] television production on videotape. ([[1981]]), and [[Michael Gambon]] in [[London, England|London]] stage production directed by [[Alan Ayckbourn]] in 1990. |

|||

==[[Subhash Chandra Bose]] on Swamiji<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| first = S.K. |

|||

| last = Bose |

|||

| title = Subhas Chandra Bose: The Alternative Leadership - Speeches, Articles, Statements and Letters |

|||

| publisher = [[Orient Longman]] |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

| isbn = 9788178241043 |

|||

| page = 244 |

|||

}}</ref>== |

|||

Swami Sahajanand Saraswati is, in the land of ours, a name to conjure with. The undisputed leader of the peasant movement in [[India]], he is today the idol of the masses and the hero of millions. |

|||

When [[Patrick Stewart]] played Othello at the Shakespeare Theater Company in [[Washington, D.C.]], he portrayed the Moor as a white man with the other characters played by black actors. |

|||

==Works by Swami Sahajanand Saraswati== |

|||

Actors have alternated the roles of Iago and Othello in productions to stir audience interest since the nineteenth century. Two of the most notable examples of this role swap were [[William Charles Macready]] and [[Samuel Phelps]] at [[Drury Lane]] (1837) and [[Richard Burton]] and [[John Neville (actor)|John Neville]] at the [[Old Vic Theatre]] (1955). When [[Edwin Booth]]'s tour of [[England]] in 1880 was not well attended, [[Henry Irving]] invited Booth to alternate the roles of Othello and Iago with him in [[London]]. The stunt renewed interest in Booth's tour. [[James O'Neill (actor)|James O'Neill]] also alternated the roles of Othello and Iago with Booth, with the latter’s complimentary appreciation of O'Neill’s interpretation of the Moor being immortalized in O'Neill’s son [[Eugene O'Neill|Eugene’s]] play ''[[Long Day's Journey Into Night]]''. |

|||

===Well Researched Books=== |

|||

1. ''[[Bhumihar|Bhumihar Brahmin]] Parichay'' (Introduction to Bhumihar [[Brahmins]]), in Hindi. |

|||

''Othello'' opened at the [[Donmar Warehouse]] in [[London]] on the 4th of December, 2007, directed by [[Michael Grandage]], with [[Chiwetel Ejiofor]] as Othello, [[Ewan McGregor]] as Iago and [[Kelly Reilly]] as Desdemona. Despite tickets selling as high as £2000 on web-based vendors, only Ejiofor was praised by critics, winning the [[Laurence Olivier Award]] for his performance; with McGregor and Reilly's performances receiving largely negative notices. |

|||

2. ''Jhootha Bhay Mithya Abhiman'' (False Fear False Pride), in Hindi. |

|||

==Adaptations and cultural references== |

|||

3. ''Brahman Kaun?'' |

|||

===Ballet=== |

|||

4. ''Brahman Samaj ki Sthiti'' (Situation of the Brahmin Society) in Hindi. |

|||

*''Othello'' ([[2002]]) has been performed as a ballet piece by the San Francisco Ballet featuring an Asian Desdemona, portrayed by dancer Yuan Yuan Tan.<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/shows/othello/othello.html Great Performances . Dance in America: Lar Lubovitch's "Othello" from San Francisco Ballet | PBS<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*A ''Othello'' ballet by [[John Neumeier]], created in 1985, is still (2008) in the repertiore of the [[Hamburg Ballet]], having had its 100th performance in 2008. |

|||

===Opera=== |

|||

5. ''Brahmarshi Vansha Vistar'' in [[Sanskrit]], [[Hindi]] and [[English language|English]]. |

|||

''Othello'' is the basis for three [[opera]]tic versions: |

|||

*The opera ''[[Otello (Rossini)|Otello]]'' (1816) by [[Gioacchino Rossini]] |

|||

*The opera ''[[Otello]]'' (1887) by [[Giuseppe Verdi]], [[libretto]] by [[Arrigo Boito]] |

|||

*The opera ''[[Bandanna (opera)|Bandanna]]'' (1999) by [[Daron Hagen]]<ref>[http://www.daronhagen.com/bandanna/ Bandanna | The opera by Daron Hagen and Paul Muldoon :: Home<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

===Film=== |

|||

6. ''Karmakalap'', in [[Sanskrit]] and [[Hindi]]. |

|||

:''See also [[Shakespeare on screen#Othello|Shakespeare on screen (Othello)]]. |

|||

There have been several [[film]] adaptations of ''Othello''. These include: |

|||

===Autobiographical Works=== |

|||

*''[[Othello (1922 film)|Othello]]'' (1922) starring [[Emil Jannings]]. [[Silent film|Silent]].<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0013469/ Othello (1922)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

1. ''Mera Jeewan Sangharsha'' (My LIfe Struggle), in Hindi. |

|||

*''[[Othello (1952 film)|The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice]]'' (1952) by [[Orson Welles]]<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0045251/ The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice (1952)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''Отелло'' (1955), [[USSR]], starring [[Sergei Bondarchuk]], [[Irina Skobtseva]], [[Andrei Popov]]. Directed by [[Sergei Yutkevich]]. <ref>See {{imdb title |id=0048455|title=Отелло}}</ref> |

|||

2. ''Kisan Sabha ke Sansmaran'' (Recollections of the Kisan Sabha), in Hindi. |

|||

*''[[All Night Long (1961 film)|All Night Long]]'' (1961) A British Adaptation in which the character of Othello is Rex, a Jazz Bandleader. Featuring [[Dave Brubeck]] and other [[Modern Jazz]] musicians.<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0054614/ All Night Long (1962)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Othello (1965 film)|Othello]]'' (1965) starring [[Laurence Olivier]], [[Maggie Smith]], [[Frank Finlay]], and [[Joyce Redman]]<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0059555/ Othello (1965)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Othello (1981 television)|Othello]]'' (1981), actually shot on videotape, part of the [[BBC]]'s complete works of William Shakespeare on television. Starring [[Anthony Hopkins]] and [[Bob Hoskins]].<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082861/ Othello (1981) (TV)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Otello (1986 film)|Otello]]'' (1986) A film version of [[Giuseppe Verdi|Verdi's]] opera, starring [[Plácido Domingo]], directed by [[Franco Zeffirelli]]. Won the [[British Academy of Film and Television Arts|BAFTA]] for foreign language film.<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091699/ Otello (1986)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Otello (1990 television)|Otello]]'' (1990) A TV film version staring [[Michael Grandage]], [[Ian McKellen]], [[Clive Swift]], [[Willard White]], [[Sean Baker]], and [[Imogen Stubbs]]. Directed by [[Trevor Nunn]]. |

|||

[[Image:Othelloiagomovie.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Laurence Fishburne]] and [[Kenneth Branagh]] as Othello and Iago respectively, in a scene from the [[Othello (1995 film)|1995 version of ''Othello'']].]] |

|||

3. ''Maharudra ka Mahatandav'', in Hindi. |

|||

*''[[Othello (1995 film)|Othello]]'' (1995) starring [[Kenneth Branagh]], [[Laurence Fishburne]], and [[Irene Jacob]]. Directed by [[Oliver Parker]].<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114057/ Othello (1995)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

4. ''Jang aur Rashtriya Azadi'' |

|||

*''[[Kaliyattam]]'' (1997), in [[Malayalam language|Malayalam]], a modern update, set in [[Kerala]], starring [[Suresh Gopi]] as Othello, Lal as Iago, [[Manju Warrier]] as Desdemona, directed by [[Jayaraaj]].<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0199669/ Kaliyattam (1997)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:OmkaraStill.jpg|thumb|250px|Still from the film [[Omkara (film)|''Omkara'']] featuring [[Saif Ali Khan]] (left) as Langda Tyagi (Iago) and [[Ajay Devgan]] as Omkara 'Omi' Shukla (Othello)]] --> |

|||

* [[O (film)|''O'']] (2001) a modern update, set in an American high school. Stars [[Mekhi Phifer]], [[Julia Stiles]], and [[Josh Hartnett]]<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0184791/ O (2001)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Othello (2001 TV film)|Othello]]'' (2001). TV film. A modern-day adaptation in modern English, in which Othello is the first black Commissioner of [[London]]'s [[Metropolitan Police]]. Made for [[ITV]] by [[London Weekend Television|LWT]]. Scripted by [[Andrew Davies (writer)|Andrew Davies]]. Directed by [[Geoffrey Sax]]. Starring [[Eamonn Walker]], [[Christopher Eccleston]] and [[Keeley Hawes]].<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0275577/ Othello (2001) (TV)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

*''[[Omkara (film)|Omkara]]'' (2006) ([[Hindi]]) is an Indian version of the play, set in the state of [[Uttar Pradesh]]. The film stars [[Ajay Devgan]] as Omkara (Othello), [[Saif Ali Khan]] as Langda Thyagi (Iago), [[Kareena Kapoor]] as Dolly (Desdemona), [[Vivek Oberoi]] as Kesu (Cassio), [[Bipasha Basu]] as Billo (Bianca) and [[Konkona Sen Sharma]] as Indu (Emilia). The film is directed by [[Vishal Bharadwaj]] who earlier adapted Shakespeare's Macbeth as ''[[Maqbool]]''. All characters in the film share the same letter or sound in their first name as in the original [[Shakespeare]] classic. It is one of the few mainstream [[Cinema of India|Indian movies]] to contain uncensored swear-words. |

|||

* [[Eloise (2002 film)|''Eloise'']] (2002) a modern update, set in [[Sydney]], [[New South Wales|NSW]], [[Australia]]. |

|||

* [[Jarum Halus]] (2008) a modern Malaysian film, in English and Malay by Mark Tan.<ref>[http://www.jarumhalus.com Jarum Halus official website]</ref> |

|||

* Othello (2008 TV movie) directed by [[Zaib Shaikh]] and starring [[Carlo Rota]] (both of [[Little Mosque on the Prairie | Little Mosque on the Prairie]] fame) in the title role. This version uses an alternate definition of "Moor" as someone of the Islamic faith, and places more emphasis on the cultural clash between Othello as a Muslim and the Christianized environments of Venice and Cyprus. |

|||

==Gallery of ''Othello'' images== |

|||

5. ''Ab Kya ho?'' |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Desdemona othello.jpg|"Desdemona" by [[Frederic Leighton]], ca. 1888 |

|||

6. ''[[Gaya]] jile mein sava maas'' |

|||

Image:Othellopainting.jpeg|"Othello and Desdemona in Venice" by [[Théodore Chassériau]] (1819–1856)]] |

|||

Image:Othello and Desdemona by Alexandre-Marie Colin.jpg|"Othello and Desdemona" by [[Alexandre-Marie Colin]], 1829 |

|||

7. ''Samyukta Kisan Sabha, Samyukta Samajvadi Sabha ke Dastavez''. |

|||

Image:Dante Gabriel Rossetti - Desdemona's Death Song.JPG|"Desdemona's Death Song" by [[Dante Gabriel Rossetti]], ca. 1878-1881 |

|||

Image:Death of Desdemona.jpg|"The Death of Desdemona" by [[Eugene Delacroix]] |

|||

8. ''Kisanon ke Dave'' |

|||

Image:John Graham A bedchamber Desdemona in Bed asleep - Othello Act V scene 2.jpg|"A Bedchamber, Desdemona in Bed asleep", from Othello (Act V, scene 2), part of "A Collection of Prints, from Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakspeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain", published by John and Josiah Boydell (1803) |

|||

Image:Salvini as Othello Vanity Fair.jpg|Italian actor Tommaso Salvini (1829-1915) as William Shakespeare's Othello, as depicted in Vanity Fair, May 22nd, 1875 |

|||

9. ''Dhakaich ka bhashan'' |

|||

Image:John McCullough as Othello.jpg|American actor John Edward McCullough (1837-1885) as Othello, 1878. Colour lithograph. Library of Congress |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===Ideological Works=== |

|||

1. ''Kranti aur Samyukta Morcha'' |

|||

2. ''[[Gita]] Hridaya'' (Heart of the [[Gita]]) |

|||

3. ''Kisanon ke Dave'' |

|||

4. ''Maharudra ka Mahatandav'' |

|||

5. ''Kalyan mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

===Works related to Peasantry and Zamindars=== |

|||

1. ''Kisan kaise ladten hain?'' |

|||

2. ''Kisan kya karen?'' |

|||

3. ''Zamindaron ka khatma kaise ho?'' |

|||

4. ''Kisan ke dost aur dushman'' |

|||

5. ''Bihar prantiya kisansabha ka ghoshna patra'' |

|||

6. ''Kisanon ki phasane ki taiyariyan'' |

|||

7. ''On the other side'' |

|||

8. ''Rent reduction in Bihar, How it Works?'' |

|||

9. ''Zamindari kyon utha di jaye?'' |

|||

10.''Khet Mazdoor'' (Agricultural Labourer), in Hindi, written in Hazaribagh Central Jail. |

|||

11.''Jharkhand ke kisan'' |

|||

12.''Bhumi vyavastha kaisi ho?'' |

|||

13.''Kisan andolan kyun aur kya?'' |

|||

14.''Gaya ke Kisanon ki Karun Kahani'' |

|||

15.''Ab kya ho?'' |

|||

16.''Congress tab aur ab'' |

|||

17.''Congress ne kisanon ke liye kya kiya?'' |

|||

18.''Maharudra ka Mahatandav'' |

|||

19.''Swamiji ki Diary'' |

|||

20.''Kisan sabha ke dastavez'' |

|||

21.''Swamiji ke patrachar'' |

|||

22.''Lok sangraha mein chapen lekh'' |

|||

23.''Janta mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

24.''Hunkar mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

25.''Vishal Bharat mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

26.''Bagi mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

27.''Bhumihar Brahmin mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

28.''Swamiji ki Bhashan Mala'' |

|||

29.''Krishak mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

30.''Yogi mein chapein lekh'' |

|||

31.''Kisan sevak'' |

|||

32.''Anya lekh'' |

|||

33.''Address of the Chairman, Reception Committee, The All India Anti-Compromise Conference'', First Session, Kisan Nagar, Ramgarh, Hazaribagh, 19 & 20 March, 1940, Ramgarh, 1940. |

|||

33.''Presidential Address, 8th Annual Session of the Kisan Sabha'', Bezwada, 1944. |

|||

33.''The Origin and Growth of the Kisan Movement in India'' (Unpublished) |

|||

''''Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali (Selected works of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati) in Six volumes has been published by Prakashan Sansthan, [[Delhi]], 2003''''. |

|||

==Translations into English== |

|||

*''Swami Sahajanand and the Peasants of Jharkhand: A View from 1941'' translated and edited by [[Walter Hauser]] along with the unedited [[Hindi]] original ([[Manohar Publishers]], paperback, 2005). |

|||

*''Sahajanand on Agricultural Labour and the Rural Poor'' translated and edited by [[Walter Hauser]] ([[Manohar Publishers]], paperback, 2005). |

|||

*''Religion, Politics, and the Peasants: A Memoir of India`s Freedom Movement''translated and edited by [[Walter Hauser]] ([[Manohar Publishers]], hardbound, 2003). |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist|2}} |

{{reflist|2}} |

||

== External links == |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{Wikisource}} |

|||

*''Sahajanand on Agricultural Labour and the Rural Poor'', edited by Walter Hauser, ISBN 81-7304-600-X) |

|||

{{Wikiquote}} |

|||

{{Commonscat}} |

|||

*Swami And Friends: Sahajanand Saraswati And Those Who Refuse To Let The Past of Bihar's Peasant Movements Become History By Arvind N. Das, Paper for the Peasant Symposium, May 1997 [[University Of Virginia]], [[Charlottesville]], [[Virginia]] |

|||

* [http://publicliterature.org/books/othello/xaa.php ''Othello''] — text by PublicLiterature.org |

|||

* [http://www.maximumedge.com/shakespeare/othello.htm ''Othello''] — Scene-indexed and searchable version of the text. |

|||

*AIKS ([[All India Kisan Sabha]]), Proceedings and Resolutions, 1954- 1959, New Delhi. |

|||

*[http://www.ibdb.com/show.php?id=6823 ''Othello'' at IBDB] lists numerous productions. |

|||

*[http://community-1.webtv.net/thebardofavon/othello/ photographs of a production of ''Othello''] |

|||

*AIUKS (All-India United Kisan Sabha), 1949, The Programme and Charter of Kisan Demands, Patna. |

|||

{{Shakespeare}} |

|||

*Bagchi, A.K., 1976, `Deindustrialisation in Gangetic Bihar, 1809- 1901' in Essays in Honour of Prof. S.C. Sarkar, New Delhi. |

|||

*Banaji, Jairus, 1976, "The Peasantry in the Feudal MOde of Production: Towards an Economic Model", Journal of Peasant Studies, April. |

|||

*Bandopadhyay, D., 1973, `Agrarian Relations in Two Bihar Districts', Mainstream, 2 June, New Delhi. |

|||

*Banerjee, N., 1978, `All the Bakcwards', Sunday, 9 April, Calcutta. Bihar, 1938, Board of Revenue, Average Prices of Staple Food Crops from 1888, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar, 1939, Legislative Assembly Proceedings, Vol. 4 Part 1, 16 January -- 15 March, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar, 1972, Legislative Assembly, Report of the Committee to Inquire into Atrocities at Gahlaur, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa, Rev(enue) Pro(ceedin)gs, 1923, Progs. No.3, Enclosure 1, Letter from Settlement Officer, Santal Parganas, 12 October 1923, para 2. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa 1924, Bihar and Orissa in 1923, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa, 1926, Bihar and Orissa in 1924-25, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa, 1929, Bihar and Orissa in 1927-28, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa, 1930, BIhar and Orissa in 1928-29, Patna. |

|||

*Bihar & Orissa, 1934, Report on the Administration of Civil Justice in the Province of Bihar and Orissa, 1933, Patna. |

|||

*BPKS (Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha), 1936, Bihar Prantiya Kisan Sabha ka Vidhan -- (Constitution of the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha), in Hindi, Patna. |

|||

*BPKS, -- a, Bihar Prantiya Kisan Sabha ka Ghoshna Patra aur Kisanon ki Maangen (Manifesto of the BPKS and Peasants' Demands), in Hindi, Bihta, n.d. |

|||

*Brahmanand, 1971, Rahul Sankrityayana, in Hindi, Delhi. |

|||

*Brown, Judith, 1972, Gandhi's Rise to Power: Indian Politics, 1915-1922, London. |

|||

*BSCRO (Bihar State Central Records Office) File 281/1929, Political (Special) Department, Sonepur Mela Kisan Sabha Meeting. |

|||

*BSCRO, File 34/1931, Letter of N.F. Peck, Shahabad District Magistrate dated 15 December 1931. |

|||

*BSCRO, File 21/1933, Agrarian Affairs, Kisan Sabhas. |

|||

BSCRO, File 163/1934, Notes and Orders on Swami Sahajanand's Gaya Report, 12 November 1934. |

|||

*BSCRO, File 16/1935, Extract from Fortnightly Report of the Commissioner of Bhagalpur, 4 April 1935. |

|||

*BSCRO, File 16/1935, Fortnighly Report from J.R. Dain, Commissioner of Bhagalpur, 2 December 1935. |

|||

*BSCRO, File 16/1935(I), report on Swami Sahajanand, Nasirganj, Shahabad district, 18 January 1935. |

|||

*Chaudhuri, B.B., 1971, `Agrarian Movements in Bengal and Bihar, 1919-1939' in B.R. Nanda, ed., Socialism in India, New Delhi. |

|||

*Chaudhuri, B.B., 1975, `The Process of Depeasantisation in Bengal and Bihar, 1885-1947', Indian Historical Review, 2(1), July, New Delhi. |

|||

*Chaudhuri, B.B., 1975a, `Land Market in Eastern India, 1793-1940', Indian Economic and Social History Review, 13 (1 & 2), New Delhi. |

|||

*Chaudhuri, B.B., 1976, `Struggle for Produce Rent in Bihar, 1793- 1930', Paper presented to Seminar at A.N.S. Institute of Social Studies, Patna, Cyclostyled. |

|||

*Collins, A., 1927, Bihar and Orissa in 1925-26, Patna. |

|||

*Das, Arvind N., 1976, `Promises to Keep', National Labour Institute Bulletin, December, New Delhi. |

|||

*Das, Arvind N., 1981, Agrarian Unrest and Socio-economic Change in Bihar, 1900-1980, Delhi : Manohar. |

|||

*Das, Arvind N. (ed.),1982, Agrarian Movements in India : Studies on 20th Century Bihar, London : Frank Cass. |

|||

*Das, Arvind N., 1992, The Republic of Bihar, New Delhi : Penguin. |

|||

*Das, Arvind N., 1996, Changel : The Biography of a Village, New Delhi : Penguin. |

|||

*Datta, K.K., 1957, History of the Freedom Movement in Bihar, Patna. |

|||

*Devanand, Swami, 1958, Virat Kisan Samaroh (Massive Peasant Convention), in Hindi, Bihar Kisan Sangh, Bihta. |

|||

*Diwakar, R.R., ed., 1957, Bihar Through the Ages, Patna. |

|||

*Engels, Frederick, 1969, "Preface to the Second Edition of The Peasant War in Germany" in Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels, Selected Works, Vol. II, Moscow. |

|||

*Gandhi, M.K., 1921, `The Zamindar and the Ryots', Young India, Vol. III (New Series) No. 153, 18 May. |

|||

*Gandhi, M.K., 1940, An Autobiography or The Story of My experiments in Truth, Ahmedabad. |

|||

*Gupta, R.L., 1934, Bihar and Orissa in 1932-33, Patna. |

|||

*Hauser, Walter, 1961, `Peasant Organisation in India: A Case Study of the Bihar Kisan Sabha, 1929-1942'. Ph.D. Thesis, Chicago University, (Forthcoming publication) |

|||

*Hauser, Walter, 1994, Sahajanand on Agricultural Labour and the Rural Poor, New Delhi : Manohar |

|||

*Hauser, Walter, 1995, Swami Sahajanand and the Peasants of Jharkhand, New Delhi : Manohar |

|||

*India, 1976, Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, New Delhi. JSES (Journal of Social and Economics Studies), 1976, `Sarvodaya and Development', Vol. IV No.1, Patna. |

|||

*Lacey, G. 1928, Bihar and Orissa in 1926-27, Patna |

|||

*Maharaj, R.N., 1976, `Freed Bonded Labour Camp at Palamau', National Labour Institute Bulletin, October, New Delhi. |

|||

*Mansfield, P.T., 1932, Bihar and Orissa in 1930-31, Patna. |

|||

*Marx, Karl, 1973 Grundrisse, Harmondsworth. |

|||

*Mishra, G., 1968. `The Socio-economic Background of Gandhi's Champaran Movement', Indian Economic and Social History Review, 5(3), New Delhi. |

|||

*Mishra, G., 1978, Agrarian Problems of Permanent Settlement: A Case Study of Champaran, New Delhi. |

|||

*Misra, R.N., 1952, Kisan ki Samasyayen (Problems of Peasants), in HIndi, Darbhanga. |

|||

*Mitra, Manoshi, 1983, Agrarian Social Structure in Bihar: Continuity and Change, 1786-1820, Delhi : Manohar. |

|||

*Mitra, N., ed, 1938, Indian Annual Register, July-December 1937, Vol. II, Calcutta. |

|||

*Narayan, K. , 1938, Bihar and Orissa in 1935-36, Patna. |

|||

*Nehru, Jawaharlal, 1936, An Autobiography, London. |

|||

*O'Malley, L.S.S., 1913, District Gazetters, Calcutta. |

|||

*Owen, G.E., 1922, Bihar and Orissa in 1921, Patna. |

|||

*Pouchepadass, J., 1974, `Local Leaders and the Intelligentsia in the Champaran Satyagraha', Contributions to Indian Sociology, New Series, No.8, November, New Delhi. |

|||

*Prasad, P.H., 1979, `Semi-Feudalism: Basic Constraint in Indian Agriculture' in Arvind N. Das & V. Nilakant, eds., Agrarian Relations in India, New Delhi. |

|||

*Prasad, R., 1949, Satyagraha in Champaran, Ahmedabad. |

|||

*Prasad, R., 1957, Autobiography, Bombay. |

|||

*Prior, H.C., 1923, Bihar and Orissa in 1922, Patna. |

|||

*Rai, Algu, 1946, A Move for the Formation of an All-Indian Organisation for the Kisans, Azamgrah. |

|||

*Ranga, N.G., 1949, Revolutionary Peasants, New Delhi. |

|||

*Ranga, N.G., 1968, Fight For Freedom, New Delhi. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1916, Bhumihar Brahman Parichay (Introduction to Bhumihar Brahmins), in Hindi, Benaras(?) |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1940, Address of the Chairman, Reception Committee, The All India Anti-Compromise Conference, First Session, Kisan Nagar, Ramgarh, Hazaribagh, 19 & 20 March, 1940, Ramgarh, 1940. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1944, Presidential Address, 8th Annual Session of the Kisan Sabha, Bezwada. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1947, Kisan Sabha ke Sansmaran (Recollections of the Kisan Sabha), in Hindi, Bihta. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1948, Gita Hridaya (Heart of the Gita), Allahabad. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, 1952, Mera Jeewan Sangharsha (My LIfe Struggle), in Hindi, Patna. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, a, Brahman Samaj ki Sthiti (Situation of the Brahmin Society) in Hindi, Benaras (?), n.d. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -b, Karmakalap, in Sanskrit and Hindi, Benaras (?) |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -c, Jhootha Bhay Mithya Abhiman (False Fear False Pride), in Hindi, Patna(?). |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -d, Kisanon ko Phansane ki Taiariyan (Plans to Ensnare Peasants), in Hindi, Bihta. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -e, The Origin and Growth of the Kisan Movement in India, Bihta, Unpublished ms. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -f, Gaya ke Kisanon ki Karun Kahani (Pathetic Plight of the Peasants of Gaya), in Hindi, Patna (?) |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -g, Khet Mazdoor (Agricultural Labourer), in Hindi, written in Hazaribagh Central Jail. See Hauser Walter, op cit. |

|||

*Sahajanand, Swami, -h, Maharudra ka Mahatandav, in Hindi, Bihta (?), n.d. |

|||

*Sankrityayana, R., 1943, Naye Bharet ke Naye Neta (New Leaders of New India), in Hindi, Allahabad. |

|||

*Sankrityayana, Rahul, 1957, Dimagi Gulami (Mental Slavery), in Hindi, Allahabad. |

|||

*Sankrityayana, Rahul, 1961, Meri Jeewan Yatra (My Journey through Life), in Hindi, Allahabad. |

|||

*The Searchlight (Patna) (newspaper). |

|||

*Shanin, Teodor, 1978, "Defining Peasants: Conceptualisations and Deconceptualisations: Old and New in a Marxist Debate", Manchester University. |

|||

*Sharma, Yadunandan, 1947, Bakasht Mahamari Aur Uska Achook Ilaaz (Bakasht Epidemic and its Infalliable Remedy) in Hindi, Allahabad. |

|||

*Singh, K.S., n.d. `Agrarian Transition in Chotanagpur', Unpublished ms. |

|||

*Sinha, A.N., 1961, Mere Sansmaran (My Recollections), in Hindi Patna. |

|||

*Sinha, Indradeep, 1969, Sathi ke Kisanon ka Aitihasic Sangharsha (Historic Struggle of Sathi Peasants), in Hindi, Patna. |

|||

*Solomon, S., 1937, Bihar and Orissa in 1934-35, Patna. |

|||

*Stevenson Moore, C.J., 1901, Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operations in Muzaffarpur District, 1892-99, Calcutta. |

|||

*Sudhakar, T.S., 1973, Lok Nayak Sswami Sahajanand Saraswati, in Hindi, Gaya. |

|||

*Sudhakar, T.S. -- , Mahapandit Rahul Sankrityayana, in Hindi, Gayaa. |

|||

*Swanzy, R.E., 1938, Bihar and Orissa District Gazetteers, Patna. |

|||

*Sweeney, J.A., 1922, Final Report on the Survey and Settlement (Revision) Operations in the District of Champaran, 1913-19, Patna. |

|||

*Wasi, S.M., 1938, Bihar in 1936-37, Patna |

|||

*Williams, R.A.E., 1933, Bihar and Orissa in 1931-32, Patna. |

|||

[[Category:English Renaissance plays]] |

|||

==External links== |

|||

[[Category:Italy in fiction]] |

|||

* [http://www.lib.virginia.edu/area-studies/SouthAsia/Misc/Sss/sahaj.html Swami Sahajanand Saraswati images] |

|||

[[Category:Shakespearean tragedies]] |

|||

[[Category:1603 plays]] |

|||

[[ |

[[af:Othello]] |

||

[[ |

[[ar:عطيل]] |

||

[[bs:Otelo]] |

|||

[[Category:Indian people]] |

|||

[[ca:Otel·lo]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Ghazipur]] |

|||

[[cdo:Ó̤-tái-lò̤]] |

|||

[[Category:Indian independence activists]] |

|||

[[cs:Othello (drama)]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Patna]] |

|||

[[cy:Othello]] |

|||

[[Category:People of British India]] |

|||

[[de:Othello]] |

|||

[[Category:Indian philosophers]] |

|||

[[el:Οθέλος]] |

|||

[[Category:Ascetics]] |

|||

[[es:Otelo]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Patna]] |

|||

[[fa:اتلو]] |

|||

[[fr:Othello ou le Maure de Venise]] |

|||

[[gl:Othello]] |

|||

[[ko:오셀로]] |

|||

[[id:Othello]] |

|||

[[it:Otello]] |

|||

[[he:אותלו]] |

|||

[[la:Othello, Maurus Venetiae]] |

|||

[[hu:Othello]] |

|||

[[nl:Othello (Shakespeare)]] |

|||

[[ja:オセロ (シェイクスピア)]] |

|||

[[no:Othello]] |

|||

[[pl:Otello]] |

|||

[[pt:Othello, the Moor of Venice]] |

|||

[[ru:Отелло]] |

|||

[[simple:Othello]] |

|||

[[sk:Othello]] |

|||

[[sr:Отело (драма)]] |

|||

[[fi:Othello]] |

|||

[[sv:Othello]] |

|||

[[tr:Othello (oyun)]] |

|||

[[zh:奧賽羅]] |

|||

Revision as of 07:26, 11 October 2008

| Othello, The Moor of Venice | |

|---|---|

Title page facsimile from the First Folio, (1623) | |

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Date premiered | 1 November 1604 |

| Place premiered | Whitehall Palace, London, England |

| Original language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Venice and Cyprus |

Othello, The Moor of Venice is a tragedy by William Shakespeare based on the short story "Moor of Venice" by Cinthio, believed to have been written in approximately 1603. The work revolves around four central characters: Othello, his wife Desdemona, his lieutenant Cassio, and his trusted advisor Iago. Attesting to its enduring popularity, the play appeared in 7 editions between 1622 and 1705. Because of its varied themes — racism, love, jealousy and betrayal — it remains relevant to the present day and is often performed in professional and community theatres alike. The play has also been the basis for numerous operatic, film and literary adaptations.

Source

The plot for Othello was developed from a story in Cinthio's the Hecatommithi, "Un Capitano Moro", which it follows closely. The only named character in Cinthio's story is "Disdemona", which means "unfortunate" in Greek; the other characters are identified only as "the standard-bearer", "the captain", and "the Moor". In the original, the standard-bearer lusts after Disdemona and is spurred to revenge when she rejects him. Unlike Othello, the Moor in Cinthio's story never repents the murder of his beloved, and both he and the standard-bearer escape Venice and are killed much later. Cinthio also drew a moral (which he placed in the mouth of the lady) that European women are unwise to marry the temperamental males of other nations.[1]

Othello's character, in particular, is believed to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the 17th century.[2]

Date and text

The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on October 6, 1621 by Thomas Walkley, and was first published in quarto format by him in 1622, printed by Nicholas Okes, under the title The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice. Its appearance in the First Folio (1623) quickly followed. Later quartos followed in 1630, 1655, 1681, 1695, 1699 and 1705; on stage and in print, it was a popular play.

Characters

- Othello, a Moor in the service of the Republic of Venice and Desdemona's husband

- Desdemona, Othello's wife and Brabantio's daughter

- Iago, Othello's ensign (standard bearer)

- Emilia, Iago's wife and Desdemona's maid

- Cassio, Othello's lieutenant

- Bianca, a courtesan involved with Cassio

- Brabantio, a Venetian senator and Desdemona's father

- Roderigo, a Venetian who harbours an unrequited love for Desdemona

- Duke of Venice, or the "Doge"

- Gratiano, Brabantio's brother

- Lodovico, Brabantio's kinsman and Desdemona's cousin

- Montano, Othello's Venetian predecessor in the government of Cyprus

- Clown, Montano's servant

- Officers, Gentlemen, Messenger, Musicians, Herald, Sailor, Attendants, servants etc.

Synopsis