Old South Arabic languages

| Old South Arabic | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

today's Yemen , Oman , Saudi Arabia , Ethiopia , Eritrea | |

| speaker | (extinct) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | (extinct) | |

The Old South Arabic languages (obsolete Himjar language , also Sayhadic ) are a group of extinct languages from the 9th century BC. BC to the 6th century AD in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, especially in Yemen . They belong to the Semitic languages . Old South Arabic was apparently superseded by Arabic in the early 7th century with the introduction of Islam in 630 ; the last dated inscription, however, dates back to 669 of the Himjar era (around 554 AD). It is not impossible that Old South Arabic as a spoken language died out as early as the 4th century AD. Old South Arabic is not a predecessor of the New South Arabic languages .

Kinship

Old South Arabic, like Classical Arabic and Hebrew, belongs to the Semitic languages , a branch of the Afro-Asian language family . Since the internal classification of the Semitic languages is not certain, there are also different views on how Old South Arabic is to be classified within this language family. The traditional model counts Old South Arabic together with Arabic, the New South Arabic languages and the Ethiosemitic languages in the South Semitic branch. Despite the name, the New South Arabic languages are not a direct successor to Old South Arabic. For a long time it was assumed that Old Ethiopian arose directly from Old South Arabic, but this view has now been refuted. More recent research suggests, however, that Old South Arabic is not a South Semitic language, but rather forms the central Semitic branch together with Arabic and the Northwest Semitic languages (including Hebrew, Aramaic ) . The clearest feature that separates Old South Arabic from the other Semitic languages is the determining suffix n , which is not found in this usage in any other Semitic language.

languages

Old South Arabic comprised several languages; the following have been handed down in writing (the years are based on the "Long Chronology", cf. Old South Arabia ):

-

Sabaean : language of the kingdom of Saba and the later Himjar ; also documented in the north-east African empire Da'amot ; very well documented, about 6000 inscriptions

- Old Arabic : 8th to 2nd century BC Chr.

- Middle Arabic : 1st century BC BC to 4th century AD (most documented)

- Late Sabaean : 5th and 6th centuries AD

- Minaic (also Madhabic ): Language of the city-states in Jauf - except Haram - or the later area-state Ma'in (documented from 8th to 2nd century BC) Inscriptions also outside of Ma'in in the trading colonies of Dedan and Mada'in Salih , in Egypt and also Delos . (approx. 500 inscriptions)

- Qatabanisch : Language of the kingdom Qataban , occupied by the 5th century BC.. BC to the 2nd century AD (almost 2000 inscriptions)

- Hadramitisch ( Hadramautisch ): language of Hadramaut , additionally an inscription from the Greek island of Delos. 5th century BC BC to 4th century AD (around 1000 inscriptions)

Of these languages, Sabaean is a so-called h language , the other s languages , since Sabaean shows an h in the third person pronoun and in the causative prefix , where the other languages show an s 1 .

Not all languages of pre-Islamic South Arabic belonged to Old South Arabic. Several incomprehensible inscriptions from Saba appear to be written in a language related to Old South Arabic, for which an ending -k was typical. Even the actual language of the Himyars , who wrote Sabaean before Islamization, does not seem to have been Old South Arabic. Arabic authors from the period after Islamization, when Old South Arabic itself was probably already extinct, describe some of its properties that differ significantly from both Old South Arabic and other known Semitic languages.

Lore

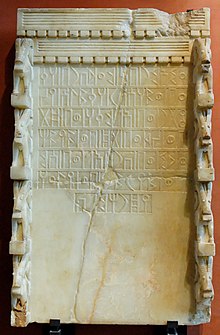

Old South Arabic was written using the Old South Arabic script , a consonant alphabet derived from the Phoenician alphabet . The number of preserved inscriptions is very high compared to other parts of the ancient world, for example Palestine , supposedly 10,000 inscriptions are preserved; the Sabaean vocabulary is about 2500 words. The inscriptions can be divided into the following groups according to the writing material and content:

- Stone inscriptions

- Votive inscriptions often contain historical reports of events that led to a dedication.

- Building inscriptions: name of the client and u. U. also historical circumstances

- Laws and Regulations

- Protocols and documents

- Atonement and penance inscriptions

- Rock graffiti

- literary texts: if such texts were ever available in large numbers, they are almost completely lost

- Inscriptions on wooden sticks and palm leaf veins (only Sabaean and Hadramitic)

- private texts

- Contracts and orders

- Inscriptions on everyday objects

A very formulaic but also precise expression is characteristic of the stone inscriptions; the wooden inscriptions written in a cursive form of script, on the other hand, have a less formulaic style.

Research history and didactics

Inscriptions from ancient South Arabia had been known in Europe since the 18th century, but it was not until Wilhelm Gesenius (1786–1842) and his student Emil Rödiger independently succeeded in deciphering the ancient South Arabic script in 1841/42. In the second half of the 19th century, Joseph Halévy and Eduard Glaser brought hundreds of Old South Arabic inscriptions, paper prints and copies to Europe. On the basis of this great material, Fritz Hommel presented a chrestomathy and an attempt at a grammar as early as 1893 . After him, the Sabaean Nikolaus Rhodokanakis in particular made further significant progress in understanding Old South Arabic . A completely new area of old South Arabic writing and writing opened up in the 1970s with the discovery of wooden sticks written on with a pen and in Sabaean language. The unknown writing and numerous incomprehensible words presented Sabaean studies with new problems, and to this day the wooden sticks are not completely understandable.

In the German-speaking countries, Old South Arabic is taught as part of Semitic Studies without there being any special chairs. Learning Old South Arabic requires knowledge of at least one other Semitic language, as learning the peculiarities of Semitic requires a language that is less fragmentary. Usually an introduction to the grammar of Old South Arabic is given, followed by reading some longer texts.

According to the system

With 29 consonantic phonemes, Old South Arabic had the richest consonant system in Semitic (according to Nebes / Stein 2004; the letters in brackets indicate the transcription):

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nonemph. | empathic | nonemph. | empathic | nonemph. | empathic | |||||||

| Plosives | stl. |

t ( |

tʼ ( |

k ( |

kʼ ( |

ʔ ( |

||||||

| sth. |

b ( |

d ( |

g ( |

|||||||||

| Fricatives | stl. |

f ( |

θ ( |

θʼ ( |

s ( |

sʼ ( |

ʃ ( |

x ( |

ħ ( |

h ( |

||

| sth. |

ð ( |

z ( |

ɣ ( |

ʕ ( |

||||||||

| Nasals |

m ( |

n ( |

||||||||||

| Lateral |

l ( |

|||||||||||

| Vibrants |

r ( |

|||||||||||

| Approximants |

w ( |

j ( y ) |

||||||||||

| lateral fricatives | stl. |

ɬ ( |

ɬʼ ( |

|||||||||

In the early days of Sabaean Studies, Old South Arabic was paraphrased using the Hebrew alphabet . The transcription of the alveolar or postalveolar fricatives is disputed; After great uncertainties in the early Sabaean period, the transcription chosen by the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum , Nikolaus Rhodokanakis and others prevailed until AFL Beeston suggested the designation by s plus index 1-3 instead . The latter designation has prevailed mainly in the English-speaking world, while z. For example, the older transcription characters, which were also taken into account in the table above, are still widespread in German-speaking countries.

The realization of the emphatic consonants ḍ, ṣ, ṭ, ẓ as velarized or ejective , as well as the emphatic q as uvular plosive or velar ejective are speculative. Likewise the determination of the sibilants s 1 / s, s 2 / š and s 3 / ś. In the oral lecture, the pronunciation of Old South Arabic is based on classical Arabic.

In the course of linguistic history, individual sound changes were evident, especially in Hadramitic, such as the change from ʿ to ʾ, from ẓ to ṣ, from ṯ to s 3 (cf. spellings like tlmyṯ for “Ptolemaios” (Minaic)). In late Sabaean s 1 and s 3 coincided to form graphic s 1 . As in other Semitic languages, n can be assimilated to a following consonant , compare vergleichnfs 1 "Souls"> ʾfs 1

Since the Old South Arabic script does not identify vowels, detailed statements about the vowels in Old South Arabic are not possible. Paragraphs of Old South Arabic names, especially in Greek, suggest that Old South Arabic, like Protosemitic and Arabic, had the vowels a , i and u . The name krb-ʾl appears in Akkadian as Karib-ʾil-u and in Greek as Chariba-el . The monophthongization of aw to ō is suggested by variants such as ywm and ym “day” (compare Arabic yawm ), Ḥḍrmwt / Ḥḍrmt / Greek Chatramot (Arabic Ḥaḍramawt ) “hadramaut”. However, since only very few words have been handed down vocalized, vocalized forms of old South Arabic names used in science are hypothetical and in some cases arbitrary.

morphology

Personal pronouns

As in other Semitic languages, Old South Arabic had pronominal suffixes and independent or absolute pronouns ; The latter are only sparsely documented outside of Sabaean. The personal pronouns are - as far as known - in detail:

| Pronominal suffixes | Independent pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabaean | Other South Arabic languages | Sabaean | ||

| Singular | 1st person | - n | ʾN | |

| 2nd person m. | - k | - k | ʾNt ; ʾT | |

| 2nd person f. | - k | |||

| 3rd person m. | - hw, h | - s 1 w (w), s 1 | h (w) ʾ | |

| 3rd person f. | - h, hw | - s 1 , - s 1 yw (qataban.), - ṯ (yw) , - s 3 (yw) (hadram.) | H | |

| dual | 2nd person | - kmy | ʾTmy | |

| 3rd person com. | - hmy | - s 1 mn (min.), - s 1 my (qataban .; hadram.) | hmy | |

| 3rd person m. | - s 1 m (y) n (hadram.) | |||

| Plural | 1st person | - n | ||

| 2nd person m. | - kmw | ʾNtmw | ||

| 2nd person f. | ||||

| 3rd person m. | - hm (w) | - s 1 m | hmw | |

| 3rd person f. | - hn | - s 1 n | hn | |

The use of the personal pronouns corresponds to that of other West Semitic languages. Appended to verbs and prepositions , the pronominal suffixes serve as object pronouns: qtl-hmw “he killed them”, ḫmr-hmy tʾlb “Taʾlab gave them both”, ʿm-s 1 mn “with them both”. Appended to nouns, they usually express a relationship of ownership: ʿbd-hw "his servant", bhn-s 1 w "his sons". The absolute pronouns served as the subject of noun and verb clauses : mrʾ ʾt "you are Lord" (nominal sentence); hmw f-ḥmdw “they thanked” (verbal sentence).

noun

Case, number, gender

The nouns of Old South Arabic distinguish the two genera masculine and feminine , the latter is usually marked in the singular with the ending - t : bʿl "Herr '" (m.), Bʿlt "Herrin" (f.), Hgr "Stadt" (m .) .), fnwt "Kanal" (f.). It has the three numbers singular, dual and plural. The singular is formed without changing the stem, the plural, on the other hand, can be formed in different ways, which can vary with the same word:

- Inner (“broken”) plurals: As in Arabic, they are very common.

- ʾ - Prefix : ʾbyt "houses" to byt "house"

- t - suffix : especially common for words with m -prefix: mḥfdt "towers" to mḥfd "tower".

- Combinations: for example ʾ prefix and t suffix: ʾḫrf “years” to ḫrf “year”, ʾbytt “houses” to byt “house”.

- without any external educational feature : fnw "channels" to fnwt (f.) "channel"

- w- / y- Infix : ḫrwf / ḫryf / ḫryft "years" to ḫrf "year" before.

- Reduplication plurals are rarely used in Old South Arabic : ʾlʾlt “gods” to ʾl “god”.

- Outer (“healthy”) plurals: In the masculine, their ending is different depending on the status (see below); in the feminine the ending is - (h) t , which probably reflects * -āt: Minaic nṯ-ht "women" to ʾnṯ-t "woman".

In Old South Arabic, the dual is already doing its job; its endings depend on the status: ḫrf-n "two years" (status indeterminatus) to ḫrf "year".

The Old South Arabic certainly knew a case inflection, which was formed by vowel endings, which is why it is not recognizable in the script; however there are traces in the spelling of v. a. of the Constructus status .

status

Like other Semitic languages, the Old South Arabic noun has several statuses , which were formed by different endings depending on gender and number. Outer plurals and duals have their own status endings, while inner plurals behave like singulars. In addition to the status constructus , which is also known from the other Semitic languages, there is also the status indeterminatus and the status determinatus , the functions of which are explained below. In detail there are the following status endings (forms of Sabaean; in Hadramitic and Minae there is an h in certain forms before the endings ):

| Stat. constr. | Stat. indet. | Stat. det. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Singular | -∅ | - m | - n |

| dual | -∅ / - y | - n | - nhn | |

| Outer plural | - w / - y | - n | - nhn | |

| Feminine | Singular | - t | - tm | - tn |

| dual | - ty | - tn | - tnhn | |

| Outer plural | - t | - tm | - tn | |

The three statuses have different syntactic and semantic functions:

- Status indeterminatus: it marks the indefinite noun: ṣlm-m "(any) a statue".

- Status determinatus: it marks the determinate noun: ṣlm-n "the statue", (hadramitic) bḥr-hn "the sea".

- Status constructus: it occurs when the noun is connected with a genitive, a personal suffix or - unlike in other Semitic languages - a relative clause:

- With pronominal suffix : (Sabaean) ʿbd-hw "his servant", (Qataban) bn-s 1 ww "his sons"

- With nominal genitive: (hadramitic) gnʾhy myfʾt "the two walls of Maifa'at", mlky s 1 bʾ "the two kings of Saba"

- With relative clause: kl 1 s 1 bʾt 2 w-ḍbyʾ 3 w-tqdmt 4 s 1 bʾy 5 w-ḍbʾ 6 tqdmn 7 mrʾy-hmw 8 “all 1 expeditions 2 , battles 3 and attacks 4 , which their two masters 8 led 5 , suggested 6 and quoted 7 "(the nouns in the status constructus are marked in italics)

verb

conjugation

Like the other West Semitic languages also distinguishes the Old South Arabian two types of finite verb forms: That with suffixes conjugated Perfect and with prefixes conjugated imperfect . In the past tense two forms can be distinguished: a short form and a form formed by n -suffix (long form or n- past tense ), which is missing in Qataban and Hadramitic. In use, the two past tense forms cannot be separated exactly. The conjugation of perfect and past tense can be summarized as follows (active and passive cannot be differentiated in the consonant spelling; example verb fʿl “make”):

| Perfect | Past tense | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short form | Long form | |||

| Singular | 1. P. | fʿl-k (?) | ||

| 2 pm. | fʿl-k | |||

| 2. P. f. | fʿl-k | t - fʿl | t - fʿl-n | |

| 3. P. m. | fʿl | y - fʿl | y - fʿl - n | |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl - t | t - fʿl | t - fʿl-n | |

| dual | 3. P. m. | fʿl (- y ) | y - fʿl - y | y - fʿl - nn |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl - ty | t - fʿl - y | t - fʿl - nn | |

| Plural | 2 pm. | fʿl - kmw | t - fʿl - nn | |

| 3. P. m. | fʿl - w | y - fʿl - w | y - fʿl - nn | |

| 3. P. f. | fʿl - y , fʿl - n (?) | t - fʿl - n (?) | t - fʿl - nn (?) | |

The perfect tense is mainly used to denote a past action, only in front of conditional clauses and in relative clauses with a conditional secondary sense does it denote a present action as in Arabic. Example: ws 3 ḫly Hlkʾmr w-ḥmʿṯt “And Hlkʾmr and ḥmʿṯt have pleaded guilty (dual)”.

The past tense usually denotes the simultaneity of a previously mentioned event or simply the present or future. There are four modes formed by prefixes :

- Indicative : it has no special feature in most languages, only in Qataban and rarely in Mina it is formed by a prefix b : bys 2 ṭ "he acts" (Qataban). With perfect meaning: w- y-qr zydʾl b-wrḫh ḥtḥr “And Zaid'il died in the month of Hathor ” (Minaic).

- Precative : it is formed with l- and expresses wishes: wly-ḫmrn-hw ʾlmqhw “ Almaqahu may grant him”.

- Jussiv : it is also formed with l- and stands for indirect commands: l-yʾt "so it should come" (Sabaean).

- Vetitiv : it is the negation 'l formed. It is used to express negative commands: w- ʾl y-hwfd ʿlbm “And no ʿilb trees may be planted here”.

Derived Tribes

Various derived stems can be formed from verbs by changing the consonantic root, which are related to this in terms of their meaning. Six such tribes are recorded in Old South Arabic . Examples:

- qny "get"> hqny (Sabaean) / s 1 qny (other languages) "sacrifice, donate"

- qwm "arrange"> hqm (Sabaean) / s 1 qm (other languages) "arrange", tqdm "fight"

syntax

sentence position

The order of the sentence in Old South Arabic is not uniform. The first sentence of an inscription always has the sentence position (particle) subject - predicate (SV), the other main clauses of an inscription are introduced by w - "and" and - like the subordinate clauses - usually have the position predicate - subject (VS). The predicate can be introduced by f -.

Examples:

| s 1 ʿdʾl w-rʾbʾl | s 3 lʾ | w-sqny | ʿṮtr | kl | ġwṯ |

| S 1 ʿdʾl and Rʾbʾl | have offered (3rd person plural perfect) | and have consecrated (3rd person plural perfect) | Athtar | all | Mending |

| subject | predicate | Indirect object | Direct object | ||

| "S 1 ʿdʾl and Rʾbʾl have offered the whole repair to Athtar and consecrated it" | |||||

| w-ʾws 1 ʾl | f-ḥmd | mqm | ʾLmqh |

| and Awsil | and he thanked (3rd person Sg. perfect) | Power (stat. Constr.) | Almaqah |

| "And" - subject | "And" - predicate | object | |

| "And Awsil thanked the power of Almaqah " | |||

In addition to sentences with a verbal predicate, Old South Arabic, like the other Semitic languages , knows nominal sentences , the predicate of which can be a noun, adjective or a prepositional phrase; the subject usually precedes:

| w-ḏn-m | wtfn | mṣdqm |

| And this one | Handover certificate (Stat. Det.) | binding (stat. indet.) |

| "and" attribute | subject | predicate |

| And this handover document is binding. | ||

Subordinate clauses

Old South Arabic has a variety of means for forming subordinate clauses through different conjunctions:

| main clause | subordinate clause | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wys 1 mʿ-w | k-nblw | hmw | ʾGreen | b-ʿbr | ʾḤzb ḥbs 2 t | |

| "and" -3. P. Pl. Imperfect | Conjunction - 3rd P. Pl. Perfect | attribute | subject | preposition | Prepositional object | |

| And they heard | that sent | this | Najranites | to | Abyssinian tribes | |

| And they heard that these Najranites (a delegation) had sent to the Abyssinian tribes. | ||||||

| subordinate clause | Postscript | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w-hmy | hfnk | f-tʿlmn | b-hmy | ||

| "and" - conjunction | 2nd person Sg. Perfect | "then" - imperative | Pronominal phrase | ||

| And if | you sent | and sign | on them | ||

| And when you send (it) sign it. | |||||

Relative clauses

In Old South Arabic, relative clauses can be marked with relativizers such as ḏ- , ʾl , mn- ; Marking is mandatory for free relative clauses. In contrast to many other Semitic languages, sumptive pronouns are rarely found in Old South Arabic.

| mn-mw | ḏ- | -ys 2 ʾm-n | ʿBdm | f-ʾw | ʾMtm |

| “Who” - enclitic | Relativizer | 3rd person singular past tense | object | "and or" | object |

| who | buys | a slave | or | a slave | |

| Whoever buys a slave [...] | |||||

| main clause | Relative clause | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ḏn | mḥfdn yḥḏr | dm | bs 2 hd | gnʾ | hgr-sm |

| Demonstrative pronouns | subject | Relativizer | preposition | Prepositional object | Possessor |

| this | the tower yḥḏr | which one | across from | Wall | your city |

| this tower yḥḏr, which (is) opposite the wall of their city. | |||||

| ʾL-n | ḏ- | -l- | -hw | smyn w-ʾrḍn |

| God - Nunation | Relativizer | preposition | Object (sumptive) | subject |

| the God | which one | For | him | Heaven and Earth |

| the God for whom heaven and earth are = the God to whom heaven and earth belong | ||||

vocabulary

The vocabulary of Old South Arabic is relatively diverse due to the diversity of the types of inscriptions, but it is quite isolated in the field of Semitic, which makes it difficult to understand. Even with the help of closely related languages such as Old Ethiopian and Classical Arabic, only part of the Old South Arabic vocabulary can be deduced, a large part has to be deduced from the context of the text, and some words remain incomprehensible. On the other hand, many words from agriculture and irrigation technology can be found in the works of Yemeni scholars from the Middle Ages and partly also in modern Yemeni dialects. Foreign loanwords are rare in Old South Arabic, only Greek and Aramaic words found their way into South Arabic inscriptions in the Rahmanistic , Christian and Jewish periods (5th to 7th centuries AD). B. qls 1 -n from Greek ἐκκλησία "church", which has been preserved in Arabic al-Qillīs as the name of the church built by Abraha in Sanaa .

swell

- ↑ a b Christian Robin: South Arabia - a culture of writing. In: Wilfried Seipel (Hrsg.): Yemen - Art and archeology in the land of the Queen of Sheba . Milan 1998. ISBN 3-900325-87-4 , pp. 79 ff.

- ↑ See Alice Faber: Genetic Subgrouping of the Semitic Languages . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): The Semitic Languages . London: Routledge, 1997. pp. 3-15. Here p. 5.

- ↑ John Huehnergard: Features of Central Semitic . In: biblica et orientalia 48 (2005). Pp. 155-203. Here p. 160 f.

- ^ A. Avanzini: Le iscrizioni sudarabiche d'Etiopia: un esempio di culture e lingue a contatto. In: Oriens antiquus , 26 (1987), pp. 201-221.

- ^ Dialects according to: Peter Stein: Zur Dialektgeographie des Sabaean. In: Journal of Semitic Studies XLIX / 2. Manchester 2004

- ↑ Peter Stein: Materials for Sabaean Dialectology: The Problem of the Amiritic ("Haramitic") Dialect . In: Journal of the German Oriental Society . tape 157 , 2007, p. 13-47 .

- ↑ Extrapolation based on samples from Beeston, Ghul, Müller, Ryckmans: Sabaic Dictionary (see bibliography)

- ↑ See: Ryckmans, Müller, Abdallah 1994; Serguei A. Frantsouzoff: Hadramitic documents written on palm-leaf stalks. In: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabien Studies , 29 (1999), pp. 55-65

- ↑ To this: P. Stein: Are there cases in Sabaean? , in: N. Nebes (Ed.): New contributions to Semitic studies. First working meeting of the Semitic Study Group in the German Oriental Society from September 11 to 13, 2000 , pp. 201–222

- ↑ For details: Norbert Nebes: Use and function of prefix conjugation in Sabaean , in: Norbert Nebes (ed.): Arabia Felix. Contributions to the language and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. Festschrift Walter W. Müller for his 60th birthday. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp. 191-211

- ↑ Norbert Nebes: The constructions with / FA- / in Old South Arabic. (Publications of the Oriental Commission of the Academy of Sciences and Literature Mainz, No. 40) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1995

- ↑ AFL Beeston: Foreign loanwords in Sabaic , in: Norbert Nebes (ed.): Arabia Felix. Contributions to the language and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. Festschrift Walter W. Müller for his 60th birthday . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp. 39-45

literature

Overview and brief descriptions

- Mounir Arbach: Le madhabien: lexique, onomastique et grammaire d'une langue de l'Arabie méridionale préislamique . (Tomes 1-3) Aix-en-Provence, 1993 (includes a lexicon, a grammar and a list of proper names in Minae)

- Leonid Kogan, Andrey Korotayev : Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) . In: Robert Hetzron (Ed.): Semitic Languages . Routledge, London 1997, pp. 157-183 .

- Norbert Nebes, Peter Stein: Ancient South Arabian , in: Roger D. Woodard (Ed.): The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008 ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9 , pp. 145-178

- Peter Stein : Ancient South Arabian . In: Stefan Weninger (Ed.): The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook . De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin 2011, ISBN 3-11-018613-6 , pp. 1042-1073 .

Grammars

- Peter Stein: Textbook of the Sabaean Language (2 volumes), Wiesbaden 2012/13 ISBN 978-3-447-10026-7

- A. Beeston: Sabaic Grammar , Manchester 1984 ISBN 0-9507885-2-X

- Maria Höfner : Old South Arabic grammar (= Porta linguarum Orientalium . Volume 24). Leipzig 1943

Dictionaries

- AFL Beeston, MA Ghul, WW Müller, J. Ryckmans: Sabaic Dictionary / Dictionnaire sabéen / al-Muʿdscham as-Sabaʾī (English-French-Arabic) Louvain-la-Neuve, 1982 ISBN 2-8017-0194-7

- Joan Copeland Biella: Dictionary of Old South Arabic. Sabaean dialect Eisenbrauns, 1982 ISBN 1-57506-919-9

- SD Ricks: Lexicon of Inscriptional Qatabanian (Studia Pohl, 14), Pontifical Biblical Institute, Rome 1989

Texts

- Alessandra Avanzini: Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions I-III. Qatabanic, Marginal Qatabanic, Awsanite Inscriptions (Arabia Antica 2). Ed. PLUS, Pisa 2004. ISBN 88-8492-263-1 .

- Barbara Jändl: Old South Arabic inscriptions on metal (epigraphic research on the Arabian Peninsula 4). Tübingen, Berlin 2009. ISBN 978-3-8030-2201-1 .

- Johann Heinrich Mordtmann : Contributions to the Minaean epigraphy , with 22 facsimiles printed in the text. Felber, Weimar 1897.

- Johann Heinrich Mordtmann and Eugen Wednesday : Sabaean inscriptions . Friederichsen, de Gruyter & Co., Hamburg 1931. Rathjens-von Wissmannsche Südarabien-Reise, Volume 1. Treatises from the field of foreign studies Volume 36; Series B, Ethnology, Cultural History and Languages Volume 17.

- Johann Heinrich Mordtmann and Eugen Wednesday: Old South Arabic inscriptions . Pontifico Instituto Biblico, Rome 1932 and 1933 in Orientalia issues 1–3, 1932 and issue 1 1933.

- Jacques Ryckmans, Walter W. Müller, Yusuf M. Abdallah: Textes du Yémen antique. Inscrits sur bois (Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain 43). Institut Orientaliste, Louvain 1994. ISBN 2-87723-104-6 .

- Peter Stein: The old South Arabic minuscule inscriptions on wooden sticks from the Bavarian State Library in Munich 1: The inscriptions of the middle and late Sabaean period (epigraphic research on the Arabian Peninsula 5). Tübingen u. a. 2010. ISBN 978-3-8030-2200-4 .

Web links

- Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions (so far includes all Hadramitic and Qatabanic as well as many Minaean and Sabaean inscriptions)

- Catalog of the old South Arabic minuscule inscriptions of the Bavarian State Library