Railway reform (Germany)

The term railway reform means the legal and organizational restructuring of the state-owned railways in Germany, by 1994 came into force Railroad Restructuring Act was introduced. Components of the rail reform include the establishment of Deutsche Bahn AG as a federal railway company organized under private law , the opening of the railways for private railway companies and the transfer of responsibility for local rail passenger transport from the federal government to the states .

Starting position

The situation of the Deutsche Bundesbahn in the Federal Republic of Germany had been characterized by constant economic decline since the 1950s. The increasing competition of motor transport as well as decades of political neglect of the railway as a mode of transport led to a long-term loss of market shares in passenger and freight transport. In addition, the repair of war damage in the 1950s and 1960s caused financial burdens for the Federal Railroad. The result was increasing debt - most recently the mountain of debt was around 34 billion euros - so that the Federal Railroad's ability to act was no longer guaranteed.

In the area of the German Democratic Republic , the Deutsche Reichsbahn enjoyed a monopoly-like position, so that the Reichsbahn was able to maintain its extraordinarily large share of the transport market until 1989. However, a shortage of materials and personnel made the infrastructure unsatisfactory, especially since the railway network had suffered considerable damage after 1945 through reparations to the Soviet Union. After reunification and the decline of the GDR economy, transport services collapsed, especially in freight traffic. In 1990 a financial requirement of 100 billion DM was estimated for the rehabilitation of the Reichsbahn within the next ten years .

Between 1950 and 1990, the railways' share of transport performance fell from 56 to 21 percent in freight transport and from 36 to 6 percent in passenger transport. The state-protected freight traffic of the Reichsbahn until reunification halved from 1990 to 1991. In 1990 the Reichsbahn had 224,000 employees, the Federal Railroad 249,000. In 1993 the Bundesbahn and Reichsbahn lost around 16 billion D-Marks (around 8.2 billion euros). The debts of both railways at that time were 66 billion D-Marks.

While the two German state railways were in an economically problematic state in 1990, politicians called for a stronger role for the railways in passenger and goods transport in order to be able to cope with the forecast increase in traffic due to the population's growing mobility needs and the opening of European markets. However, the two state railways were neither economically nor organizationally in a position to do this, especially since the organization of the railway in the form of an authority did not allow flexible action on the transport market. Thus the Federal and State Railways could hardly do anything to counter the competition of road and air traffic .

In order to develop a sustainable form of organization for rail traffic in Germany, the Federal Ministry of Transport set up the Government Commission Rail from 1989 to 1992, which developed a concept for the reform of the rail system in Germany, which finally resulted in the 1993 Railway Reorganization Act.

On December 2, 1993, the German Bundestag voted with 558 votes in favor, 13 against and four abstentions for the necessary legislative package. In addition to Article 87 of the Basic Law , around 130 laws were changed. These changes were necessary in order to establish Deutsche Bahn AG, to separate the tasks of the public services of general interest from the entrepreneurial tasks of the railways, to regionalize local rail passenger transport and to transfer the officials of the former Federal Railroad into a temporary employment relationship between DB AG and Federal Railroad Assets. After approval by the Federal Council , Deutsche Bahn AG was entered in the commercial register in Berlin-Charlottenburg in January 1994.

The changes took effect on January 1, 1994. With the rail reform, the demands of EC Directive 91/440 / EEC for non-discriminatory access to the rail network in Germany were implemented.

On December 4, 1997, the Supervisory Board of Deutsche Bahn approved the second stage of the rail reform. On January 1, 1999, five independent stock corporations were founded under the umbrella of Deutsche Bahn AG, which largely corresponded to the previous corporate divisions : DB Reise & Touristik AG emerged from the long-distance transport division, and DB Regio AG from the local transport division , DB Cargo AG from the Freight Transport UB, DB Netz AG from the Track UB and DB Station & Service AG from the Passenger Stations UB .

Legal and organizational changes to the rail reform

Basic principles

The rail reform essentially implemented three basic principles:

- Conversion of the Bundesbahn and Reichsbahn into a new, privately organized federal railway company, Deutsche Bahn AG, and debt relief for the new company

- Creation of non-discriminatory access to the railway network for private railway companies

- Transfer of responsibility for local rail passenger transport to the federal states, including financial responsibility (regionalization)

Organization under private law

Through a private-law organization (stock corporation) of rail traffic, on the one hand the goal of generating profits is a new company goal and at the same time the railway should be able to act more flexibly in the market. The company's financial capacity to act should also be guaranteed through debt relief, including the pension costs.

For this purpose, the previous federal authorities, the Federal Railroad and Reichsbahn , had to be split up : the business parts, the operation of the lines, stations and trains were brought into the new Deutsche Bahn AG (DB AG) ( Federal Railways ), and the sovereign tasks in the area of approval and corporate supervision were transferred to the newly established Federal Railway Authority , while the federal railway assets were assigned the debts of the Federal and Reichsbahn as well as the real estate not necessary for the railway operation for further utilization. The civil servants previously working for the state railways were also assigned to the federal railroad assets, which the civil servants lent to DB AG under temporary employment agreements. In order to be able to shoulder the enormous investments in modernizing the railway infrastructure, the German federal government promised DB AG annual grants amounting to billions and interest-free loans for a long time.

The newly founded DB AG was initially organized into four business areas, which were based heavily on the organizational structures of the two state railways:

- Passenger transport division, responsible for local and long-distance transport

- Freight transport division

- Traction & Works division, responsible for rolling stock, depot and repair shop

- Network division, responsible for the infrastructure

As part of the second stage of the 1999 rail reform, the responsibilities within DB AG were further unbundled, so that DB AG changed into a holding company with five independent subsidiaries:

- DB Reise & Touristik AG (later DB Fernverkehr AG), responsible for long-distance passenger transport

- DB Regio AG, responsible for local passenger transport

- DB Cargo AG (later Railion; 2008–2016 DB Schenker Rail; since then again DB Cargo), responsible for freight transport

- DB Netz AG, responsible for lines and line equipment (tracks, signal systems, overhead lines, etc.)

- DB Station & Service AG, responsible for the train stations

As part of the second stage, the locomotives, wagons and depots were also divided among the individual subsidiaries, so that the previous Traction & Works division could be omitted. So are z. B. ICE trains owned by DB Fernverkehr, while the S-Bahn railcars are owned by DB Regio.

In the future, a sale of DB AG as a whole or individual subsidiaries is conceivable, once the company is ready for the capital market. However, the law stipulates that the infrastructure must remain majority-owned by the federal government.

Free network access

A second central component of the rail reform was the creation of a transport market in rail traffic, on which other railway companies can offer their transport services in addition to DB AG. In order to make this possible, a distinction was made between the railway companies in railway companies (EVU) and railway infrastructure companies (EIU), whereby a company can also be both EVU and RIU. An RIU operates a rail network and enables RUs to use the railway facilities for train operations for a fee (train path fee). In order to enable free competition between the RUs, non-discriminatory access was stipulated by law as part of the rail reform. This means that every RU has the right, within the framework of the existing line capacities, to have its trains run on the railway lines of the EIUs for a fee. All RUs that apply to use the infrastructure must have the same terms and conditions with regard to timetable design and fees. An IM may therefore not arbitrarily favor or disadvantage a certain RU.

Since the regulations regarding non-discriminatory network access repeatedly led to disputes, the Federal Railway Authority was assigned the task of a regulatory authority in 2001. In 2006 this task was transferred to the Federal Network Agency . In 2005, with the Railway Infrastructure Usage Ordinance (EIBV), the regulations regarding non-discriminatory network access were further specified. Furthermore, the European Directive 2001/14 / EC defines non-discriminatory network access also at European level.

Regionalization

The third pillar of the rail reform is what is known as regionalization . This describes the change in responsibility for local rail passenger transport from the federal government to the federal states on January 1, 1996. In addition, the Regionalization Act came into force in 1994 . The states were free to delegate this responsibility further, so that various regulations have developed.

The organization of local transport was regulated by the individual countries in local transport laws. In doing so, u. a. in Bremen, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate municipalities and special-purpose associations commissioned to order the transport services. In Bavaria , Brandenburg , Schleswig-Holstein , Thuringia (and other federal states) this function was taken over by the federal states. In Lower Saxony , municipal associations were established for the greater Hanover and Braunschweig areas, and a regional railway company was set up for the rest of the country. Only in Hamburg no local traffic law was introduced and instead the Hamburger Verkehrsverbund was converted into a GmbH .

The change of responsibility also includes financial compensation. The federal states receive so-called regionalization funds annually from the federal government , which are intended to finance the regional rail transport . The amount of the funds was initially based on the expenditures that would be necessary to be able to offer the regional rail transport at the level before the rail reform. In 1996 a total of eight billion D-Marks were available, in 1997 around twelve billion. This amount was gradually increased to EUR 7 billion by 2005 and then reduced again to EUR 6.6 billion by 2008. In the coming years, the amount is expected to grow again by 1.5% annually.

Simultaneously with the change of responsibility, the ordering principle was introduced in local rail transport. This means that the public transport authorities (federal states or special purpose associations) order the provision of local rail transport services from the RUs. The RU provides the services on its own within the framework of the quality standards agreed with the contracting authorities. It receives a fee for this from the transport authority. Depending on the design of the contract, the RU retains the fare income (so-called net contract) or passes it on to the transport authorities (so-called gross contract). Transport contracts are typically concluded for a period of 8 to 15 years. The award of the transport services to the RUs can take place in the course of a tender as well as in the form of a direct award, i. H. without an invitation to tender through a direct price request to the RUs. However, in a ruling in 2011 , the Federal Court of Justice stipulated that direct awards are only permitted in special cases and for short periods of time, while a tendering process usually has to be carried out.

In the late 1980s , Schleswig-Holstein was the first federal state to sign a contract for regional transport with what was then the Federal Railroad.

In 2012, in view of what they saw as decreasing competition, several large transport companies called for more regional transport services to be awarded directly in the future . The Association of Private Railways (mofair) spoke out against direct awards.

Implementation and consequences of the rail reform

The change in the legal framework has had far-reaching consequences for the railways in Germany since 1994. Due to the considerable investment requirement, the long depreciation periods for rail vehicles of 15 to 30 years as well as the necessary establishment of new administrative and entrepreneurial structures, the rail reform cannot be regarded as complete to this day. Added to this are the changes at European level that will lead to the Europeanization of the large railway companies.

Corporate development DB

The newly founded DB AG was faced with the task of uniting the two previous state railways Deutsche Bundesbahn and Deutsche Reichsbahn and at the same time organizing itself privately. The previous regional division of responsibilities into federal and Reichsbahndirectors was replaced by a structure according to business areas, which in turn established regional branches. The various business areas are coordinated at the holding company level. It was soon started to outsource tasks from the five parts of the group and run them as independent subsidiaries. For example, DB AutoZug GmbH , which organizes traffic with road and night trains, S-Bahn Berlin GmbH and S-Bahn Hamburg GmbH as operators of S-Bahn networks. In order to be able to successfully assert itself against private competition in local traffic on branch lines, DB AG has been running a so-called SME offensive since 2000 , in which the route infrastructure and train operation on regional routes are again combined in one company so that it can operate more efficiently and closer to the market . In the meantime, several such regional networks have emerged.

In the area of operational business, DB began a comprehensive modernization and investment program, especially in the area of the vehicle fleet. In addition to modernizing the local transport fleet, the focus was primarily on the procurement of new locomotives and multiple units, which made it possible to make up some of the investment backlog from the time of the Federal Railroad. For example, between 1994 and 2006 more than 1000 new electric locomotives and more than 700 local electric multiple units were purchased. In the area of the route network, investments are primarily made in signaling and safety technology, in the construction of supra-regional new lines (Hanover-Berlin, Cologne-Frankfurt , Munich-Nuremberg ) and the new construction of the railway infrastructure in the greater Berlin area. Far-reaching plans to completely rebuild the tracks in Frankfurt am Main and Munich, however, have since been abandoned.

The costs caused by the restructuring and the large investment requirement led to renewed indebtedness of the DB Group in the order of 20 billion euros (2005). At least it was possible to achieve that the operative business can be carried out cost-covering and a profit could be made in 2005. In recent years, DB Regio and DB Netz have proven to be particularly successful financially, each with around a third of the profit. The logistics division, for example, generated only 13.7% of the profit with a turnover share of 41%.

The federal government intended to privatize parts of Deutsche Bahn. After several years of discussion, the coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD agreed in 2008 on a privatization draft known as the holding model , which provided for the outsourcing of the passenger and freight transport division of DB to a holding company called DB Mobility Logistics , which was partly to private investors should be sold. In contrast, the infrastructure divisions (network, train stations, energy supply) should remain fully owned by DB, which in turn should remain fully owned by the federal government. In May 2008, the CDU / CSU and the SPD submitted a motion to the Bundestag that private capital should acquire a 24.9 percent stake in DB Mobility Logistics AG. The sales proceeds were to be used in roughly equal parts for an “innovation and investment program for rail traffic”, an increase in equity and for the federal budget. The DB AG should remain fully owned by the federal government.

The initial public offering of DB Mobility Logistics, which had already been prepared for October 27, 2008, was stopped at short notice in October 2008, as the financial market crisis that had meanwhile resulted in only revenues of around four billion euros instead of the initially planned eight billion euros. Rail boss Grube has now described the failure of the IPO in 2008 as luck .

Development in local public transport

Local rail transport has become the most successful of all three types of transport since the rail reform. As a result of the commitment of the federal states and private competition, the range of services was soon improved through the introduction of integral cycle timetables (e.g. Allgäu-Schwaben-Takt , Rheinland-Pfalz-Takt ) and the renewal of the vehicle fleet. Occasionally, local passenger traffic was resumed on routes on which there had previously been no passenger traffic for years (e.g. Grünstadt-Eisenberg , Winden-Wissembourg , Mayen-Kaisersesch , Dissen-Bad Rothenfelde-Osnabrück ). Between 1996 and 2006, local passenger traffic was resumed on 31 route sections with a length of 441 km, plus some routes on which trains only run for tourist traffic on weekends. However, even after 1994, passenger traffic was discontinued on some routes, especially in rural areas in the new federal states .

Initially, the allocation of services to private railway companies was mainly limited to less frequented, diesel-powered secondary lines, while operation on the electrified main lines and in the metropolitan areas was outsourced directly to DB Regio. In 2011, a decision by the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) largely prohibited direct awarding of tenders. Since then, the more heavily frequented subnetworks have also been tendered, with both DB and private competitors winning important tenders.

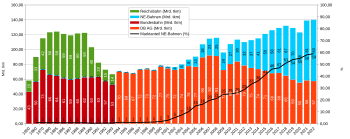

The share of private railways in the train services in local passenger transport increased from 3% to 33% (2017). The total number of passengers rose from 1.36 billion (1993) to 2.21 billion (2008) to 2.75 billion (2017) and has therefore doubled since 1993. In the awards of 53 million train kilometers carried out in 2013, the companies won in DB Group 72%. In 2012, 51 million train kilometers were awarded by tender, with DB winning 45%. The main competitors of DB in local rail transport are Transdev , Netinera , Benex , Abellio and Keolis .

The regionalization funds continue to be the most important building block for the financing of local rail passenger transport. It is true that operating costs have been reduced through tenders and additional revenues have been achieved through increased passenger numbers, but the fare revenues still only cover part of the costs. According to a study by the Federal Network Agency, 35% of the revenues in local rail passenger transport in 2005 came from fare revenues and 65% from order fees. The share of market revenues increased to 40% by 2008 and to 45% by 2017.

Development in long-distance passenger transport

While the development of passenger numbers and transport performance in long-distance passenger transport was initially positive in the 1990s, the early 2000s were marked by a significant slump, so that transport performance and passenger numbers fell below the level before the rail reform. The main reasons for this are the discontinuation of the interregional network and entrepreneurial errors on the part of DB in connection with the introduction of a new price system (2002). Both the number of passengers and the volume of long-distance passenger transport have increased steadily since 2004, and in 2017 they reached a new record of 41 billion passenger kilometers.

The abolition of the InterRegio network was ultimately a consequence of the separation of responsibilities for local and long-distance transport that came about with the rail reform: While local transport is ordered and paid for by the federal states from the railway companies, long-distance transport is carried out independently by the railway companies. The InterRegio network as a link between local and long-distance traffic, which could be used without surcharge with local transport tickets, could not be operated economically on some routes by DB Fernverkehr, so it gave up these connections. As a result, the federal states were forced to order fast local transport connections ( Regional Express ) from DB Regio or other railway companies if they wanted to prevent rural regions from being cut off from supra-regional transport.

As before, DB has a quasi-monopoly in long-distance passenger transport and operates more than 99% of all long-distance trains (2012). Only individual trains in a few routes have so far been established by private competitors. Georg Verkehrsorganization has been operating the Berlin – Malmö night express train since 2000, the first private long-distance train in Germany since the rail reform. Furthermore, Veolia Verkehr tried several times up to 2014 to set up long-distance connections under the name InterConnex in various relations . In the summer of 2012, a new private provider of long-distance trains was added with Hamburg-Cologne-Express . However, the opening of the long-distance bus market resulted in the end of some private long-distance transport providers, while others are currently refraining from entering the market. The Interconnex on the Leipzig – Berlin – Rostock route was explicitly discontinued on the grounds of long-distance bus competition. With the abolition of sleeper and car trains with the timetable change in December 2016, in addition to ÖBB under the name Nightjet , some private competitors also became active in this field , and in December 2016 Locomore entered the scene with a Berlin-Stuttgart connection. Locomore had to cease operations after five months in May 2017 due to bankruptcy . The product still exists, it is managed by Leo Express .

Development in freight transport

The development in freight transport has been inconsistent since the rail reform: while in the area of block train and combined transport private RUs were able to gain a foothold and thus make freight transport customers more attractive offers than before, the development in single wagon transport was the other way around: with the implementation of the MORA operating concept C the DB AG concentrated the single wagon traffic on larger customers, so that the service of whole regions in the rail freight traffic was given up. Partly there was collaboration between DB AG with private utilities, which in some areas to operate the railway sidings took over.

The corporate strategy of DB AG in freight transport is geared towards streamlining domestic activities to larger customers (MORA C) on the one hand and international expansion on the other: by taking over the freight transport divisions of the Dutch and Danish state railways, cooperating with other foreign railways and purchasing the two globally active forwarding companies Schenker and Bax were able to advance the prerequisites for establishing international transport chains. In order to make the international orientation of its freight transport division clear to the outside world, DB AG renamed it Railion in 2003 and DB Schenker Rail Germany in 2009 . On March 1, 2016, the company was renamed DB Cargo Germany .

Despite the entry of private RUs into the freight transport market, the transport volume initially fell from 337 million tons (1994) to 299 million tons (2000) and only reached the level of 1994 with 346 million tons in 2006. After the economic slump in 2009, transport volumes rose again reached the level of 1991 with 412 million tons in 2017. The transport distances and thus the transport performance increased from 70 billion ton-kilometers (1994) to 86 billion ton-kilometers (2004) and reached a peak of 115.7 billion in 2008, before increasing to the 2005 level collapsed, but then recovered and rose to 129 billion tonne-kilometers by 2017, about twice as much as in 1993. The share of private RUs in freight transport increased from 1.3% (1993) to 1.9% (2000) , 24.5% (2009) to 47% (2017). The modal split initially decreased from 16% to 15% (2000) and has since increased to 19.3% (2017).

Development of the route network

The route network has been owned by DB Netz since the rail reform . This makes timetable routes available to its sister companies and private competitors for a fee. However, the conditions under which this happens caused serious disputes between DB AG and the private railway companies, especially in the first few years, as the legally required non-discriminatory access to the network was not guaranteed by DB AG. The first train path pricing system from 1996 was judicially declared invalid because it benefited DB subsidiaries. There was also an antitrust investigation against the train path pricing system in 1998, before DB withdrew it itself. As a consequence of these disputes, the official supervision of the allocation of timetable routes was improved through the creation of a regulatory authority (Federal Railway Authority, later Federal Network Agency).

The condition of the route network has repeatedly led to discussions and the DB brought the charge of not investing enough in the network, especially in the secondary route network. Between 1994 and 2006, the DB route network was reduced from 40,385 kilometers to 34,128 kilometers and around 13,847 kilometers of track and 58,616 switches and crossings were dismantled. Since 2008 only very few and short routes have been shut down.

Development of the private railways

In 1994, the private railroad sector was essentially characterized by smaller railroad companies that operated individual branch lines with little traffic or, as works railways, were part of an industrial enterprise. Accordingly, the vehicle fleet and organizational forms were not designed for the operation of supra-regional connections, locomotives of larger power classes for route service were hardly available, and electric locomotives were almost completely missing. There were also only a few passenger and freight cars available.

Only in the course of time could larger, nationally active railway companies be formed. Some of these were start-ups (e.g. Prignitzer Eisenbahn GmbH ), companies that had emerged from factory railways (e.g. rail4chem ), municipal companies (e.g. HGK ) and international transport providers (e.g. eurobahn ). In the meantime, a process of concentration has begun in which larger corporate groups have been formed through takeovers. Foreign state railways are also increasingly involved in Germany. The Dutch State Railways Abellio and the Italian State Railways took over the EVU Arriva Deutschland ( today: Netinera ). The French State Railways are active in Germany through their subsidiaries Keolis , Captrain and ITL and the Danish State Railways participated in the Vias .

Particularly in the first few years, the private railway companies had difficulties with the procurement of locomotives and wagons, as the DB no longer sold any vehicles to its competitors before 2012. Thus, the private EVUs were dependent on vehicles from abroad or new construction vehicles, and in some cases museum vehicles were even reactivated. In the meantime, leasing companies for rail vehicles have been established that procure new vehicles and then rent them to the EVUs (e.g. Dispolok , Alpha Trains , Railpool, etc.). In addition, personnel service providers emerged who made specialist staff such as locomotive drivers available to private railway companies. Since access to the DB own Güterverladeanlagen, workshops and depots for private utilities or is possible only with difficulty, private utility companies mainly use private or municipal facilities or build their own.

Financing the rail reform

In order to be able to finance the railway reform - so the official reason - the mineral oil tax was increased by 7 pfennigs on January 1st, 1994. With the additional tax revenue, the old debts of the two former state railways DB and DR were to be paid off.

The financing of network maintenance is regulated in the service and financing agreement between the federal government and DB.

The rail reform in a European context

Similar to Germany, the development of the railways in the second half of the 20th century also took place in most of the other Western European countries. Falling market shares in passenger and freight transport as well as high financial deficits shaped the image of the state railways. At the same time, the development of the railway system within national boundaries created technical and organizational island solutions that made continuous train traffic across European national borders difficult.

Therefore, since the beginning of the 1990s, the European Union has been promoting a policy of restructuring the railways in the European Union and creating a European rail market. As an important transit country, Switzerland largely followed this policy even though it is not an EU member. The first step was Directive 91/440 / EEC , which provided for separate accounting for infrastructure and rail operations, stipulated non-discriminatory access to rail infrastructure in cross-border combined transport and called on the states to rehabilitate and discharge their state railways. In a series of further directives, which were combined into the first (2001), second (2004) and third railway package (2007), non-discriminatory network access was extended to all cross-border freight traffic and cross-border passenger traffic. Furthermore, the creation of national network conditions and regulatory authorities are required to secure access. To improve interoperability, standardized regulations for train driver training, safety regulations and passenger rights were introduced.

In addition to organizational standardization, the EU is striving to standardize the technical framework conditions in rail transport and has founded the European Railway Agency to promote the development of uniform technical standards. In the long term, the European rail traffic management system ERTMS is intended to replace the previous national train control systems on international connections in order to increase interoperability in rail traffic .

The regulations created by the rail reform in Germany go beyond the EU requirements in most areas. In particular, all freight and passenger transport in Germany is open to competition and foreign transport companies can therefore operate rail transport in Germany without restrictions, including purely domestic transport and cabotage . In contrast, in many other European countries certain areas of rail transport are still protected from competition. In a country comparison, Germany is one of the European countries that have pushed the opening of rail transport to competition the furthest, both in terms of legal regulations and their practical implementation. Nevertheless, has the European Commission , an infringement procedure initiated against the Federal Republic of Germany and other EU countries, as it does not look ensures the independence of infrastructure and train operations, as long as the infrastructure company DB remains power supply of the DB Group.

literature

- Deutsche Bahn, central area of corporate communications (ed.): The rail reform . Deutsche Bahn AG, Frankfurt 1994 (112 pages).

- Tim Engartner: The privatization of Deutsche Bahn. About the implementation of market-oriented transport policy. Dissertation. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008.

- Jürgen Gies: The strategies of the German railway reform and discussions about the development tendencies of the liberalized railway sector - an investigation from a discourse-analytical perspective. Dissertation. University of Heidelberg 2006. ( digitized version )

- Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies (CER) (Ed.): Railway reforms in Europe - A position determination. (Series: Railway Legislation). DVV Media Group | Eurailpress, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-7771-0321-7 .

- Maximilian Meyer: The failed rail reform. Causes - consequences - alternatives. Büchner-Verlag, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-941310-20-9 .

- Hans-Joachim Ritzau et al: The rail reform - a critical review. Ritzau − Verlag Zeit und Eisenbahn, Pürgen 2003, ISBN 3-935101-04-X .

- Christian Kuhlmann: Regionalization of local rail transport - opportunities and limits. Tectum, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-8288-5106-1 .

- Erich Preuss: The broken railway. 1990–2000 facts - legends - background. transpress Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-613-71154-0 .

- Erich Preuss: Railway in transition. Facts - Backgrounds - Consequences. transpress Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-613-71244-X .

Web links

- Extract from the Railway Reorganization Act

- Article about the rail reform and regionalization in Westphalia

- 20-year balance sheet of the railway reform from 1994 to 2014. (PDF, 164 pp.) Response of the federal government to the major question from the DIE LINKE parliamentary group. In: Drucksache 18/3266. German Bundestag, November 24, 2014, accessed on December 2, 2014 (1.15 MB).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing : "Traffic in Numbers" ( Memento of the original from November 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Heinz Dürr: Set on the common track. In: The world. September 25, 2010, accessed August 5, 2017 .

- ↑ a b 10 years of rail reform. In: Eisenbahn-Revue International , Issue 3/2004, ISSN 1421-2811 , pp. 114–116.

- ↑ Second stage of the rail reform. In: Eisenbahn-Revue International . Issue 1/2, 1998, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 2.

- ↑ a b Detlef Visser: Competition on the rails. In: TRAIN . No. 12, 1995, without ISSN, pp. 16-21.

- ↑ Ulrich Limbach: BGH ruling will in future almost rule out direct awards in local rail passenger transport. In: Railway courier . 4/2011 ISSN 0170-5288 , p. 7.

- ↑ Eberhard Happe: Zug-Zwang. The future of rail passenger transport - Part 1. In: Railway courier . 8, No. 215, 1990, ISSN 0170-5288 , pp. 34-37.

- ↑ Kerstin Schwenn: Little can be seen of the competition on the railways . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . February 22, 2012, p. 12 online .

- ^ Annual report 2005 of DB AG

- ↑ Alliance Rail for All: Deutsche Bahn, Alternative Annual Report 2011. (PDF; 3 MB)

- ↑ German Bundestag (ed.): Motion of the parliamentary groups of the CDU / CSU and SPD: Future of the railways, railways of the future - further developing the railroad reform (PDF; 64 kB). Printed matter 16/9070 dated May 7, 2008.

- ^ Welt Online: Railway privatization: Government pulls emergency brake , October 10, 2008

- ↑ DB AG: Optimism and Investments. Lok-Magazin 5/2010, p. 10.

- ↑ a b c d Deutsche Bahn AG, competition reports 2004 to 2014 ( Memento of the original from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Traffic in figures 2015/2015. DVV / BMVI, archived from the original on December 23, 2015 ; Retrieved December 19, 2015 .

- ^ Fritz Engbarth: Closures and reactivations. In: EK Special. 81 10 years of regionalization in local rail transport. 2006.

- ↑ Decision of February 8, 2011 on the award of service concessions for local rail transport (file number X ZB 4/10)

- ^ Kristina Walter: Eisenbahnverkehr 2008. Federal Statistical Office, Economy and Statistics 5/2008.

- ↑ a b c Competitor Report Railway 2013/2014. (PDF; 9.5 MB) mofair e. V. and Network of European Railways e. V., November 2013, archived from the original on December 3, 2013 ; Retrieved November 27, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e Railway Market Survey 2018, Federal Network Agency, December 2018

- ↑ Federal Network Agency: Railway Market Survey 2009 (PDF; 239 kB), p. 21.

- ↑ destatis ( Memento from August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ DB Cargo Deutschland AG - DB Schenker Rail AG becomes DB Cargo AG ( memento of March 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 9, 2016

- ↑ Roland Fischer, Eisenbahnverkehr 2004, Federal Statistical Office, Economy and Statistics 5/2005 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Roland Fischer, Eisenbahnverkehr 2005, Federal Statistical Office, Economy and Statistics 5/2006 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Kristina Walter: Eisenbahnverkehr 2006. Federal Statistical Office, Economy and Statistics 6/2007 ( Memento of the original from January 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Karl-Dieter Bodack: The Deutsche Bahn: data - facts - criticism: suggestions for realignment. (PDF; 78.5 KiB) April 9, 2008, accessed November 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Commission of the European Communities: White Paper, A Strategy for the Revitalization of the Railways in the Community (PDF) July 30, 1996.

- ↑ Rail Liberalization Index 2011. IBM Global Business Services, April 20, 2011 (PDF; 2.3 MB)

- ↑ EU Commission is suing Deutsche Bahn. In: Handelsblatt.com , June 25, 2011

- ↑ EU keeps Deutsche Bahn in its sights due to group integration. In: derwesten.de , October 19, 2011