Principia (staff building)

The Principia ( plural word ) were the administrative and religious center at almost every fortified garrison site of the Roman army . From the middle of the 1st century BC Until the beginning of late antiquity, its structure followed a more or less standardized floor plan, which usually included a central courtyard with a surrounding portico , two suites of rooms on the two narrow sides and a basilica with an adjoining row of other rooms in the rear. The flag sanctuary (Aedes) and the unit's cash desk (aerarium) were also located in the center of this rear suite . Due to its location at the intersection of the most important road axes of a fort, the importance of the staff building is underlined. In the literature, the word middle building is therefore also used for this structure. The appearance of this central building has undergone a multitude of changes over the centuries. In contrast to the fortified garrison types, the term principia in the Roman Marschlagers denoted the central area in front of the praetorium , where u. a. the troop commander owned his quarters.

Marching camp

From the ancient literary sources it appears that there were principia in the marshals of the Roman army . It is not clear from the information that has been handed down what this term clearly refers to. One of these important ancient texts is an incompletely preserved short text entitled De munitionibus castrorum ("From the fortifications of the forts"), which comes from a collection compiled by a surveyor named Hyginus Gromaticus . Hygin, however, is not the author of this military writing of unknown origin. Therefore it is also referred to as pseudo-hygin in the specialist literature in connection with De munitionibus castrorum . The period of origin of this writing is associated with the 1st or 2nd century AD. It emerges from it, for example, that the Principia must have been a central square within the camp, which also gave its name to the Via principalis , which ran within a Roman camp . The via principalis connected the two gates opposite on the two long sides of the fortification. De munitionibus castrorum mentions a few other facilities around the camp commandant's tent, such as the place where priests, the so-called augurs , observe the flight of birds (auguratorium) in order to explore the will of the gods, and a podium for the speeches of the troop leaders (Tribunal) . Identifying the remains of such temporary facilities during an excavation is very difficult due to the perishable materials used and the often poor state of preservation. Only the more firmly established camps, which were set up for longer-term sieges, offer good viewing opportunities and allow conclusions to be drawn about the marching camps. For example, the archaeologist Adolf Schulten (1870–1960) succeeded in recording the interior of the camp at Masada . He assumed, among other things, to have recognized the remains of a tribunal, an auguratory and the locations of several altars and a niche for placing the legionary eagle directly in front of the praetorium. The Trajan Column in Rome also offers illustrative material for the configuration of the surroundings at the Praetorium. In one scene, Emperor Trajan (98–117) is shown at an altar in front of the general tent. Next to the praetorium are the legionary eagles and a vexillum . It is possible that this important and central place in front of the general tent with all its individual, independently existing building and functional complexes formed the space that ancient writings refer to as the Principia . This could also explain the plural form of the word.

Stand storage

development

By the middle of the 1st century AD

The principia of the standing camps may have developed from the various functional buildings that were loosely grouped around the praetorium of the marching camps . At permanent garrison locations, the building of the praetorium moved behind the staff building or was built on its flanks. The urban, civil forum architecture is assumed to be the model for the early and mid-imperial staff building . The basic form of the Principia was completed in the 2nd half of the 1st century, as evidence in the legionary camps of Mirebeau-sur-Béze (France), Nijmegen (Netherlands), Neuss (Koenenlager), Vetera I and Inchtuthil (Scotland) show . But there were also changes later, for example in the design of the flag shrine. Therefore, the central building typical of the middle of the 2nd century AD was gradually built. By comparing different sites that have preserved the remains of fort buildings from different epochs, the detachment of the residential wing and the reorientation or regrouping of the building elements can be gradually traced. In many cases it has been shown that the staff buildings of the cohort forts were simpler than those of the legions, but there were also components that are explicitly indicative of the type of garrison used by the auxiliary troops. These include the elongated, rectangular transverse halls above the Via principalis . The floor plans of individual staff buildings that deviate from the standard grid could possibly be explained by the construction histories and regional circumstances that are unknown or only partially comprehensible today. With the size of the stationed troops, the size of the Principia also varied in many ways . However, comparisons between forts in Germania and Britain, which have the same workforce and size, show that the staff buildings on the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes were larger.

Early pre-forms of the development towards the well-planned, unified building scheme are for the 2nd century BC. By the campaigns of Scipio Aemilianus from 134 to 133 BC. Occupied in Spain. At that time, the residential and administrative wings still formed a unit, as the excavations in the castles of Castillejo and Peña Redonda showed the circumvallation of Numantia . However, the further development of more solid command centers in long-term camps up to the Augustan period is still unknown. The early administration tracts bordered directly on the private quarters of the general and were built as lightweight huts (hibernacula) during long-lasting sieges or other more permanent army operations . The floor plan was not strictly standardized, but it is noticeable that the room lines arranged in the square opened up towards the Lagerstraße. The courtyard-like shape of the Principia , open to the street , can still be recognized by the significantly further developed command post in the Augustan legionary camp Neuss , period C. Due to the stone buildings of the middle imperial period on the Roman border fortifications, the relatively strongly standardized floor plan of this epoch has become known.

The gradual development is exemplarily clear when comparing the early Dangstetten legionary camp with the Rödgen fort in the Wetterau and with the Oberaden and Haltern legionary camps . In the center of the Dangstetten camp, a building can be seen with an inner courtyard as its center. Traces of rows of rooms can also be seen. However, the finding does not allow any distinction between a residential wing and office rooms.

In line with the Oberaden complex, a central portico courtyard was also built in the Rödgen fort. A building wing with a complex interior division was connected to the southern long side. While another wing of the building was built on the western side of the courtyard, there is no one on the north side. The scientists agree that the Rödgen staff building also had living spaces in addition to the offices. However, it is no longer possible to precisely assign the individual building functions. Oberadern in turn shows a further stage of development. Here the living area was already outsourced. The portico courtyard surrounded by columns also existed in this camp, but it was considerably widened at the rear. Behind it was a series of rooms that closed off the building at the rear. Instead of the center to be expected in this room escape flags sanctuary was in its place, access to the behind the Principia located Praetorium . The findings for the staff building in the legionary camp of Haltern were similar. Two construction phases could be recorded on the building. In period 1 it seems as if the portico courtyard was joined to the rear by a basilica, which could also apply to period 2. Perhaps there was also a second, rear courtyard here. In both construction phases, however, the staff building ends with a rear suite, the center of which is a passage to the adjoining praetorium . The cellar pits found in the second period in front of the final rows of chambers in the area of the presumed basilica or the second courtyard can possibly be regarded as aeraria .

A further stage of development in the design of the Principia was reached with the headquarters of the Legio XXI Rapax in Vindonissa , built in AD 47 . The rear basilica with the concluding suite of rooms stands out clearly there. Similar to Haltern, a cellar-like room explored in this basilica can be understood as the location of the troop coffers. In contrast to the Haltern camp, however, there is no longer a passage to the Praetorium at the rear : the row of chambers is closed. The inner courtyard in Vindonissa was not surrounded by a portico, but there were two sets of rooms on the flanks that served as armamentaria (armory). The staff building in the Vetera I legionary camp from the time of Emperor Nero (54–68) is already a fully developed type that already combines all the structural elements that are typical from this point in time.

2nd century AD

The flag sanctuary, which was previously housed in a rectangular room, is now equipped with a semicircular apse at the rear. The design of the sanctuary with apses had become common in the Roman castles, especially in the Germanic area, from the middle of the 2nd century. In addition, the rear rooms of the staff building in particular will be partially equipped with hypocaust heating. Both wood and earth and stone staff buildings could be equipped with mostly red, simple frescoes. For example, corresponding finds from the Upper Pannonian fort Ács-Vaspuszta (Ad Statuas) were known.

The floors in the rooms of the staff building were very individual. It was not only the principia of the wood-earth forts that had floors made of rammed earth. In the Pannonian fort Százhalombatta-Dunafüred (Matrica) , the flag sanctuary of the stone construction phase from the Middle Imperial period was equipped with a clay floor, while the adjoining rooms had partly terrazzo floors and at times brick floors . The surface of the inner courtyard could also range from clay floors and various gravel to different types of stone paving. The use of marble as a building material for the staff buildings does not seem to have been all that widespread. A special feature of the Ács-Vaspuszta fort was a marble column with a spiral-shaped shaft that was found by the excavators of the furnishings in the courtyard of the Principia. attributed.

3rd century AD

As can be shown with the examples of Künzing and Kapersburg , the rear room lines with the flag sanctuary were architecturally emphasized in many cases. It can be observed that in some cases the expensive hypocaust heating that had existed up to that point was shut down or replaced by canal heating . The much simpler technique of duct heating became common in late antiquity and, in contrast to the hypocaust, survived antiquity. The slow disappearance of the transverse hall from the architectural principle of the staff building, which began in the 2nd century, is attested by the findings at Niederbieber Fort . It can also be observed that the imperial cult replaces the cult around the standard in meaning.

4th century AD

In late antiquity, the appearance of the administrative wing changed significantly. It took on individual forms, which may have been based on local conditions. In a number of well-known late antique staff buildings, such as the Luxor fort , which used a temple as the centerpiece of the camp, the architectural specifications of the early and middle imperial era can no longer be recognized. The individualization was also evident at the Dionysiados fort in Fayum, Egypt . Instead of the inner courtyard, a row of columns was erected there, which led to the flag shrine. In the case of the Principia of the Mosian fort Iatrus from the Constantinian period, the representative building with its solid masonry and the walls decorated with paintings was based on the older specifications in a simplified manner, but was relatively smaller. The staff building of Iatrus was directly connected to the only gate of the fort via a via praetoria which was developed as a colonnaded street . In late antiquity, the monumental character of the Principia remained in general . preserved, but the buildings sometimes showed a very primitive, fleeting execution. The same restrictions often applied to the design of the rooms and the courtyard.

The reduction in the size of the fort areas, which can often be observed, or the adaptation of the buildings to new troop structures and often fewer units, resulted in the demolition and conversion of the previous interior development in the late period. For example, the area of the flag sanctuary of the principia of Fort Százhalombatta-Dunafüred, which had previously been demolished, was converted into a waste pit in post-Valentine times, while the crew at Fort Ács-Vaspuszta dug beehive-like grain pits through the layers of the former staff building. In other places, the presence of civilians - at least in parts of the fort area - could also be determined. This could be demonstrated at the Rhaetian fort Eining (Abusina) at the Upper Germanic small fort Haselburg and at the Pannonian fort Baracspuszta (Annamatia) .

Individual structural members

Groma

The main entrance to the Principia was located directly at the intersection of the two most important camp streets within a fort, the Via principalis connecting the two gates on the long sides and the Via praetoria coming from the main gate facing the enemy . In many cases, this access was monumental, for example at the legion camp of Nijmegen. Here the entrance was designed in the form of an arched monument. The construction of the entrances to the staff building in the Vindonissa legionary camp was similar. As a special feature, however, the staff building was pushed over the crossing point so that the Via principalis led across the Principia via an entrance in each of the two building flanks and touched the rear basilica along the length of the building. This particular structural form is known from the civil Gallic forum architecture. But there are also special deviations in the castles of the auxiliary troops, as is evident in the Hungarian Danube Fort Budapest-Albertfalva , whose stone buildings were built in the early 2nd century. Here the Via principalis also leads directly into an inner courtyard, the square of which opens onto the street.

Above the main entrance to the staff building there was usually a building inscription above the cornice, which named the ruling emperor, the builder and the construction team. In some cases, the entrance to the Principia was also designed in the form of a large gate building that spanned the intersection of the two main camp roads. This structure can take the form of a quadrifron , as happened in Lambaesis , Dura-Europos , Lauriacum or Aquincum . Based on an inscription handed down from Lambaesis, the name of this gate building on the ideal camp center is also known. This point, located exactly in the middle of the Via principalis , was the main survey point during the construction of a Roman camp site and was called - like the surveying instrument of the same name installed there - Groma .

An important structural detail from the outer front of a staff building was handed down from the Remagen fort. There the garrison commander at the time had the camp's sundial replaced from his private fortune in 218 AD, as it no longer displayed the time correctly due to age. Water clocks, which may also have been set up in the Principia , were also used especially for sun-free days and nights . Because this is where the night guards gathered before the winding up to take their orders.

patio

An always uncovered, square or rectangular inner courtyard formed the central and connecting element of almost all excavated staff buildings in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The various structures with their different functions that are necessary for a commandant's office are grouped around it in a square. It was only from the second half of the 3rd century that this architectural element lost its importance, as a courtyard was occasionally dispensed with from then on.

The main entrance to the courtyard area was reached via the Via principalis . In the auxiliary forts, from the 2nd half of the 1st century AD, the front transverse hall often had to be passed in order to get there. In Theilenhofen the former gravel of the farm was obviously in good condition when it was excavated. Pavement could be found at other garrison sites. The simplest execution was a ground reinforcement with the help of pounded earth. The inner courtyard was usually surrounded by porticos on three, sometimes on four sides. Depending on the type of construction, these entrances could be supported by wooden or stone pillars. Elsewhere, such as the Scottish fortress Bar Hill on Antoninus Wall , the luxury of stone columns with capitals was afforded. Finds indicate that barriers made of metal or wood were incorporated between the pillars or columns, so that direct access to the inner courtyard was only possible at predetermined points. The found on the edge of some patios stone troughs for the eaves show that the whorls to the farms dropping towards towing or gable roofs had. The inventory of the courtyards also occasionally included wood-paneled shaft wells, which were mostly placed in the corners. Other fixtures could be water tanks that had to be built when the water table was too deep or the ground was too rocky. In the underground of the courtyards there were often water pipes that lead sewage out of the building. A pipe and water purification system was discovered in the courtyard of the Principia of Benwell, which had five stone settling basins.

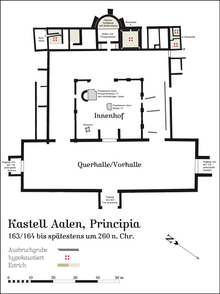

Sometimes foundations have been preserved in the middle of the open space that could have once supported a statue or honorary column. The larger than life statues of Julia Domna († 217) and Emperor Severus Alexander (222–235 AD ) were apparently placed together in the courtyard of Fort Murrhardt . The excavator Dieter Planck suspected a water basin for the Principia -Hof von Aalen , behind which the portrait of a spring nymph could have stood in a semicircular apse. A square floor plan in the courtyard of the Saalburg was interpreted by the excavators as the foundation of a tribunal. Similar inner courtyard foundations emerged from the ground , for example, in the Hessian fort Arnsburg and in the Romanian Casei. Their interpretation is controversial. In the center of the courtyards there was often a consecration altar in honor of the personification of military discipline and order (Disciplina) . In some places the Disciplina Augusti - loyalty and inner solidarity with the emperor - was venerated there. Together with the flag shrine, the consecration stones and altars set up in the inner courtyards testify to the religious significance that the staff building had for the troops.

Armories and prisons

On the two long sides of the inner courtyard, behind the portico, there were mostly rows of chambers, the entrances to which were opened from the courtyard. These rooms served - at least in the archaeologically verifiable cases - as magazines and armamentaries (Armamentaria) , as shown at Künzing Castle . It is assumed that the armories in particular could have been housed in their own buildings within the garrisons, as not all Principia had appropriate premises. An inscription from the Dutch fortress in Leiden-Roomburg attests to the new construction of an apparently independent armamentary. But other functions are also conceivable for the rooms discussed. At the southwest corner of the Principia von Pfünz was still an iron chain with a lockable ring in which the lower leg bone of a prisoner was stuck. The excavators therefore suspected a prison wing within the staff building. The prisoner himself is said to have been burned to death during a final, all-destructive enemy attack with the Principia .

basilica

The wing of the staff building, which closes off the inner courtyard at the rear, was architecturally often higher due to its importance, at least in parts. In the early days there were further office rooms (tabularia) and, in the case of independently operating units, the flag sanctuary, in which the standards of the troops were kept and the image of the emperor to be worshiped stood. But even under Emperor Augustus (31 BC - 14 AD), a new building element can possibly already be found in the Haltern legionary camp. A large, roofed transverse hall had been installed there between the back office and the inner courtyard. As an inscription from the English Reculver testifies, this hall was called the Basilica . Like the market halls in the Roman forums in the legionary camps, these basilicas could have up to three naves and most of them were probably of a corresponding height. Only the archway of the main entrance to the transverse hall at the Legion Fort Burum in Dalmatia was completely preserved in 1774 with a height of nine meters. The total height of the front wall at Fort Arbeia / South Shields on Hadrian's Wall in northern England was also described as at least nine meters after the excavations. As was shown, among other things, during the investigations in the Hesselbach fort , period 2, these basilicas could also be found in command offices that had been built using pure wood construction technology. Some principia , which do not have basilicas, had at least one particularly wide portico in front of the rear room, as is attested by the findings from the Numidian Gemellae or from Niederbieber.

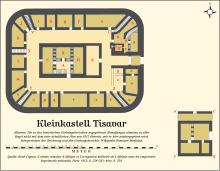

In a number of transverse halls it was found that there were also rooms on both narrow sides. In the Lambaesis legionary camp , there were inscriptions relating to the Scholae . These were the officers' meeting rooms in the garrisons. The basilica of a fort was also used to erect consecration altars and statues. In the Stockstadt Fort , the foundations of an altar were excavated at its original location. It was located in front of the flag sanctuary, to which there was direct access from the basilica. The striking similarity of the transverse hall with the city basilicas makes it clear that many administrative, ceremonial, religious and legal meetings could have taken place here. Due to a lack of evidence, however, nothing more can be said about the functions of this building section. The importance of the basilica has apparently decreased as the 2nd century progressed. Although the principia of the Százhalombatta-Dunafüred fort , which was only built in stone after the Marcomann Wars (166–180), were equipped with such a hall, the principia of the Aalen riding fort on the Rhaetian Limes , for example, built in 163/164 AD do not already have a basilica more. Here the mighty vestibule, which was in front of the Principia as a head building , could have fulfilled their function. Why some forts had a basilica and others did not, can hardly be determined without a doubt.

Writing rooms

In the office of a castle from the middle imperial period, a considerable amount of administrative work had to be done every day for the files. The standardized daily reports included the morning report, which gave the officers information about the exact number of crews on the day. This report also included information about detachments and feedback. The archives of the Principia also contain the personal files on each individual soldier. In addition to personal details, the number of years of service, promotions and salary were recorded there. Research also knows general official correspondence, vacation lists, watch lists and marching orders, as well as receipts for transfers, promotions and legal notices as well as receipts for requisitions. The office in the staff building was subordinate to an administrative officer ( Cornicularius ) , his deputy ( Actuarius ) and often several typists (Librarii) . The office of the administrative officer was evidently mostly in the rear suite of the Principia on one side of the flag shrine and could include up to two rooms. An inscription was found in the eastern corner of the Niederbieber fort, which was dedicated by a scribe to the genius of the tabularium of unity. The adjoining room contained metal fittings, locks, and hinges that might have come from filing cabinets or chests. An inscription from Dura Europos also shows that the tabularium was in one of the corner rooms.

Further rear service and meeting rooms

The rear chambers in some forts were equipped with at least one heatable room . In Niederbieber, a consecration to the genius of the Vexillarii and Imaginiferi was found in the room next to the flag shrine . It was therefore assumed that a schola , a meeting and cult room for standard bearers could have been there. In the Lambaesis legionary camp, the two rooms to the left and right of the flag shrine also served as a scholae, according to the inscriptions . An inscription from the Aquincum legionary camp (Budapest) mentions the renovation of the guard house for the soldiers who were on duty at the standards. Several papyri from the Syrian Dura-Europos also testify that a guard stood in front of the flag shrine. The oath of these guards is also known from the same garrison:

- quod imperatum fuerit faciemus et ad omnes tesseram parati erimus

Translation: “We will do what is commanded; we are ready to carry out every command. "

The defense of the standard had the highest priority because, among other things, they represented the personified embodiment of unity. In Niederbieber, for example, the skeleton of the standard bearer (signer) with a standard was found in an adjoining room of the flag sanctuary. The soldier had defended his flag to the last in the last devastating attack by the Germans. Perhaps the room in which the signer was found was also his office, because the bookkeeping and cash management, which were also housed in the rear rooms of the Principia , belonged to the administrative work of the field sign carrier .

Flag sanctuary and troop coffers

In the middle of the rear suite of the staff building was the flag sanctuary in which the standards of the troops were kept for independently operating Roman units. Inscriptions provide several names for the area of the flag sanctuary. As the already mentioned inscription by Reculver testifies, the term Aedes principiorum was used there. The words Sacellum , Aedes aquilae , Adyton , Domus signorum and - from the Reiterkastell Aalen - Capitolium have become known. In 1992, the ancient historian Oliver Stoll , citing critical remarks by the archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz , restricted that the current use of these terms is in principle artificial or simplistic, since the actual historical reference point for the different words is unknown. Karlheinz Dietz , another ancient historian, also expressed himself critically in 1993 about the attempt by Géza Alföldy to reconstruct the text in the building inscription from Aalen. In his opinion, the place [c] ap [i] / tol [i] has been incorrectly added to cum pri [ncipiis] ("the flag sanctuary and the staff building"). In his opinion, the correct reading would be praetorium cum principiis ("the commandant's house and the staff building"), since the flag sanctuary and the principia formed a structural unit and therefore would not have been mentioned separately in a building inscription. For many researchers like the archaeologist Marcus Reuter or Stoll, however, this conclusion was not correct. According to the archaeologist Dieter Planck, there is no ancient evidence for equating the word Sacellum with the flag shrine . Since the term was used in Roman times for simple state places of worship and private sanctuaries, it is not immediately permissible for him to relate the word Sacellum to the flag sanctuaries. Stoll confirmed this statement. For him, only the archaeological sources that can be evaluated with the help of epigraphy, such as building inscriptions and papyri, reflect true sacred toponymy . Therefore, in addition to Aedes principiorum and Capitolium , the locality names Aedes aquilae and Adyton, known from a papyrus from the second quarter of the third century AD, have a much higher authentic value. The term domus signorum , used by the Roman poet Publius Papinius Statius (around 40 - around 96) in a poetic passage, should, however, only be used with caution, as it is not clear whether the terminology can be trusted in this case.

The flag shrine played the most important role within the shrines of a garrison. With the emperor's portrait erected there and the almost religiously venerated standard, this part of the building can be seen as the center of the staff building.

Flag sanctuaries were initially housed in rectangular rooms, but after the middle of the 2nd century AD many received semicircular apses as a special emphasis . In addition, their architectural importance was often highlighted inside by vaults and their spatial structure emerged from the back wall of the Principia . This structural measure had a decisive influence on the external architectural appearance of a staff building. The standards of the unit were, as Tacitus (around 58 to 120) reported, placed on a raised podium on the back wall or in the semicircle of the apse. In Fort Collen , Wales, this bench was found on the flanks and the back wall of the sanctuary, in the north of England fortress Risingham there was a podium with three steps leading up to it and in Aalen the semicircular imprint of the stone bench in the floor of the apse was still visible . The apse of the flag sanctuary in the Constantinian Principia of Fort Iatrus was separated from the rectangular transverse hall in front of it by a 0.60 meter high step made of mighty monolithic swelling stones. The flooring consisted of burnt brick panels. The inlet grooves visible in the swell stones could have belonged to a wooden balustrade, which was interrupted in the middle by an entrance that was accessible from the level of the transverse hall via a wooden staircase.

On important holidays of the Roman army, which were recorded in an official festival calendar ( called feriale Duranum after a surviving copy ), there was the festival rosalia signorum , celebrated in May , the festival of the rose- adorned standards . In the courtyard of the Principia , the unit stood up and watched as the standards were decorated with rose garlands in a solemn act. An honor to the gods was part of the ceremony. Another important ceremony was celebrated on the birthday of the standards (natalis signorum) . This festival was celebrated on the respective founding days of the troops on which they received the standard. There are other official celebrations at which the standards played an important role. In addition to the standard symbols, at least some units also set up altars and statues of gods in the flag sanctuaries. A figure of genius was found in the Limes Fort Kapersburg and parts of a bronze statue came to light in Theilenhofen . In the course of time the imperial cult pushed the importance of the flag cult more and more into the background in the army's holiday calendar. This is illustrated by a papyrus from the year 232 AD for the Syene Fort in Aswan , Upper Egypt , which describes the camp sanctuary as Caesareum (imperial sanctuary). As the finds from the area of the flag sanctuaries testify, other deities may have found their place there, for example the genius of the troops and Hercules or Fortuna.

Usually the troop coffers were also kept in the flag sanctuaries. This was where the funds intended for salaries and material purchases were located. As the late antique military writer Flavius Vegetius Renatus reports, every soldier was required to keep half of his pay in the cash register "with the standards" (ad signa) . This should prevent people from deserting. Since Vegetius is often not clear from which point in Roman military history his traditions originate, this note cannot be presented as generally valid. Nevertheless, with the help of the preserved accounts, it was possible to prove that the soldier had to accept fixed deductions. In addition to clothing and shoes, food and probably also bedding were billed. There were also "social contributions" from which the death benefit of the individual soldier and occasional banquets were financed. Vegetius reports that the money was administered by the flag bearers (Signiferi) . The discovery of a chest key in the Neuss legionary camp , which bears the punched inscription centuria Bassi Claudi / L. Fabi signiferi , fits this message . Translation: "Property of the standard-bearer Lucius Fabius from the centurion of Bassus Claudius."

Research suggests that the chests, sacks, or baskets containing the money in most of the 1st century AD wood-and-earth forts stood right on the floor of the sanctuary. In some places, such as the pre-Flavian garrisons of Baginton (Central England) and Oberstimm Fort (Danube), wood-paneled pits were also found in this area of the Principia . From the Flavian-Traian period at the latest, wood and earth camps could also have stone cellars for their troop coffers , as was the case in the northern English fort Brough-by-Bainbrige . However, these additional protective measures were more or less solidly developed; individual features in a fortification are by no means always to be found during the excavations. In some forts, the cash register was not stored in the flag shrine, but in one of the adjoining rooms. This could be observed , for example, at the castles Kastell Chesters and Kastell Benwell on Hadrian's Wall.

The flag sanctuaries are often the most massive building parts of the Principia . It happens that only the flag sanctuary of a staff building has been expanded in stone.

As rare finds of various types of garrison show, bronze tablets of law were attached to the walls at or in the flag sanctuary, on which the special rights and privileges of the soldiers, such as tax exemptions, were written down. The boards contained, for example, the requirements for tax exemptions, whereby, among other things, a gradation was made between active, honorable dismissed ( Honesta missio ) and those who had left for health reasons (Causaria missio) . The boards also dealt with changes in administrative processes, for example the issue of military diplomas , and were able to stipulate how dishonored soldiers should be treated. On one of these tablets of the law, in the military camp Brigetio was found is held the procedure of publishing, "must in every single military camp (by singulaquaeque castra) , near the flags (apud Signa) , as a bronze plaque (in tabula aerea) be immortalized (consecrari) ".

lobby

Before the middle of the 1st century AD, the square of the Principia was often closed with a one-sided, open stone or wooden portico (column arcade). The main entrance was also located here, and a building inscription was often placed above it. Previously, as in the Neuss legionary camp, period C, the square of the Principia in this area towards the camp street simply remained open or was separated from the via principalis by the less attractive rear wall of the arcades of the inner courtyard (Haltern, periods 1 and 2) . As early as 90 AD, one of the oldest examples in Künzing Castle was a large wooden vestibule that lay over the Via principalis and served various purposes. This structure was particularly widespread in the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes and, more rarely, in England. It is completely absent from the staff buildings of the legionary camps. Instead, Gromae appear there. Research suggests that roll calls and exercises took place there in bad weather. This could be derived from a reference by Flavius Vegetius Renatus and the local weather conditions. In addition, justice may also have been given here. Since nothing is known exactly about the function of this building, much remains unclear. The excavations in the Germanic and Rhaetian provinces have shown that a number of vestibules, which were many times wider than the Principia itself, are architecturally connected to their neighboring buildings. However, the stone construction of these vestibules in the auxiliary troop forts apparently only took off in the Antonine period from the middle of the 2nd century AD. Up until the beginning of the 3rd century, they were structurally improved. Usually the vestibules had wide entrances on both front sides, which sometimes had larger porches, as has been demonstrated in Aalen, among other places. At the front, facing Via praetoria , there was often just a single gate, which could also be architecturally emphasized by a porch. However, some principia have several entrances at this point, as is attested by the Buch fort . Many vestibules show sophisticated architectural features that reinforce the representative character. In the English fort Ribchester there was even a side aisle in the vestibule, which was formed by eight columns. Some of these halls were only added to existing staff buildings at a later date, as could be observed for the early 3rd century AD at the Lower Pannonian fort Intercisa .

The commandant's residence (praetorium) was usually located next to or behind the staff buildings .

literature

- László Borhy, Dávid Bartusm, Emese Számadó: The bronze tablet of Philip the Arab from Brigetio . In: László Borhy u. a. (Ed.): Studia Archaeologica Nicolae Szabó LXXV annos nato dedicate , Budapest 2015, pp. 25–42.

- Rudolf Fellmann : The Principia of the legionary camp Vindonissa and the central building of the Roman camps and forts. Vindonissa Museum, Brugg 1958.

- Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building. (= Small writings on the knowledge of the history of the Roman occupation of Southwest Germany. 31). Limes Museum and others, Aalen and others 1983.

- Rudolf Fellmann: Principia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 23, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017535-5 , pp. 458-462. limited preview in Google Book search

- Henner von Hesberg : Design principles of Roman military architecture. In: Henner von Hesberg (Hrsg.): The military as a cultural carrier in Roman times. (= Publications of the Archaeological Institute of the University of Cologne ). Archaeological Institute of the University of Cologne, Cologne 1999, pp. 87–115.

- Anne Johnson , edited by Dietwulf Baatz : Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD in Britain and in the Germanic provinces of the Roman Empire. (= Cultural history of the ancient world . 37). 3. Edition. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X .

- Harald von Petrikovits : The interior structures of Roman legion camps during the principate's time. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1975, ISBN 3-531-09056-9 ( Treatises of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften 56).

- Harald von Petrikovits: The special buildings of Roman legion camps. In: Legio VII gemina. Diputación Provincial, León 1970, pp. 229-252. Reprinted in: Harald von Petrikovits: Contributions to Roman history and archeology. Volume 1: 1931-1974. (= Bonner Jahrbücher. Supplements 36). Rheinland-Verlag et al., Bonn 1976, ISBN 3-7927-02889-4 , pp. 519-545.

- Marcus Reuter : On the inscription equipment of Roman auxiliary staff buildings in the north-western provinces of Britain, Germania, Raetia and Noricum. In: Saalburg yearbook. 48, 1995, ISSN 0080-5157 , pp. 26-51.

- Tadeusz Sarnowski: For the statues of Roman staff buildings. In: Bonner Jahrbücher. 189, 1989, ISSN 0938-9334 , pp. 97-120.

Remarks

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, p. 15.

- ^ Anne Johnson : Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 13-21.

- ^ Hygin, De munitionibus castrorum , 11-12.

- ^ A b Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany , 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, p. 22.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 23, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017535-5 , p. 461.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , pp. 13-123.

- ↑ Ludwig Wamser (ed.): The Romans between the Alps and the North Sea. Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2615-7 , p. 27.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles . Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 152.

- ^ Dénes Gabler (ed.): The Roman Fort at Ács-Vaspuszta (Hungary) on the Danubian limes. Part 2. BAR, Oxford 1989, p. 642.

- ^ Péter Kovács : The principia of Matrica. In: Communicationes archeologicae Hungariae 1999, pp. 49-74, here, p. 69.

- ^ Dénes Gabler: Use of marble in the northern part of Upper Pannonia. Relationship between art and business. In: Gerhard Bauchhenß (Ed.): Files of the 3rd International Colloquium on Problems of Provincial Roman Art Creation. Bonn 21.-24. April 1993. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7927-1516-3 , p. 43.

- ↑ Heinz Heinen , Hans H. Anton, Winfried Weber : History of the Diocese of Trier . Volume 1: In the upheaval of cultures - late antiquity and early Middle Ages. Paulinus, Trier 2003, ISBN 3-7902-0271-1 , p. 516 (publications from the Trier diocese archive).

- ^ Gerda von Bülow: The Fort of Iatrus in Moesia Secunda: Observations in the Late Roman Defensive System on the Lower Danube (Fourth-Sixth Centuries AD). In: Andrew G. Poultier (Ed.): The transition to late antiquity on the Danube and beyond . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-726402-7 , pp. 463-466 (Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 141).

- ^ Bernhard Döhle: On the late Roman military architecture. The Limes Fort Iatrus (Moesia Secunda). In: Archeologia. 40, 1989, p. 51.

- ^ Péter Kovács : The late Roman Army. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 33.

- ^ Dénes Gabler (ed.): The Roman Fort at Ács-Vaspuszta (Hungary) on the Danubian limes. Part 2. BAR, Oxford 1989, p. 86.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Nuber Centurial Fort Haselburg. In: Dieter Planck (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Roman sites from Aalen to Zwiefalten. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , p. 360 ff., Here, p. 361.

- ^ Péter Kovács: Annamatia Castellum In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 121.

- ↑ AE 1989, 580 .

- ↑ Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus: Military camp or marble workshops: new investigations in the eastern area of the work and quarry camp of Simitthus / Chemtou. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 , p. 69.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 140.

- ↑ CIL 8, 2571 and 2571b.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 55.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 125.

- ↑ Oliver Stoll: Roman Army and Society. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07817-7 , p. 186.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd completely revised edition. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 124.

- ↑ The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire. Department B, No. 11, p. 33, note 1.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, p. 16.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8824 .

- ↑ a b AE 1962, 258 .

- ^ Péter Kovács: The late Roman Army. In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): The Roman army in Pannonia. Teleki Lázló Foundation, Budapest 2003, ISBN 963-86388-2-6 , p. 110.

- ^ AE 1986, 528 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 7752 .

- ↑ Oliver Stoll: Roman Army and Society . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07817-7 , p. 768.

- ↑ CIL 13, 7753 .

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 130.

- ↑ Harald von Petrikovits: The special buildings of Roman legion camps. In: Harald von Petrikovits: Contributions to Roman history and archeology Volume 1. Rheinland-Verlag 1976, ISBN 3-7927-0288-6 , p. 527 (first 1970).

- ↑ CIL 3, 3526 .

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 132.

- ^ AE 1989, 581 .

- ↑ Oliver Stoll: Sculpture equipment for Roman military installations on the Rhine and Danube - The Upper German-Rhaetian Limes . Scripta Mercaturae, St. Katharinen 1992, ISBN 3-928134-49-3 , p. 5.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Dietz: The renewal of the Limes Fort Aalen from the year 208 AD. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica. 25, 1993, pp. 243-252.

- ↑ Marcus Reuter: On the inscription equipment of Roman auxiliary staff buildings in the north-western provinces of Britain, Germania, Raetia and Noricum. In: Saalburg yearbook. 48, 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ Dieter Planck: Arae Flaviae. New investigations into the history of the Roman Rottweil. Müller & Gräff, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-87532-061-1 , p. 82, footnote 136.

- ↑ Oliver Stoll: Between integration and demarcation: The religion of the Roman army in the Middle East. Studies on the relationship between the army and civilian population in Roman Syria and neighboring areas. Scripta Mercaturae, St. Katharinen 2001, ISBN 3-89590-116-4 , p. 262.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, p. 17.

- ^ A b c Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 131.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles . Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 152.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd completely revised edition. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 123.

- ^ Bernhard Döhle: On the late Roman military architecture. The Limes Fort Iatrus (Moesia Secunda). In: Archeologia. 40, 1989, p. 51.

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, p. 18.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 133.

- ^ Hans Schönberger: Fort Oberstimm. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-7861-1168-5 , p. 98.

- ^ Anne Johnson: Roman castles. Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 136.

- ↑ László Borhy, Dávid Bartusm, Emese Számadó: The bronze panel of the Act of Philip the Arab Brigetio . In: László Borhy u. a. (Ed.): Studia Archaeologica Nicolae Szabó LXXV annos nato dedicate , Budapest 2015, pp. 25–42; here: p. 29.

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Fort Hesselbach and other research on the Odenwald Limes . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-7861-1059-X , p. 32 ( Limes research 12, studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube).

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Fort Hesselbach and other research on the Odenwald Limes . Mann Verlag, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-7861-1059-X , p. 145 ( Limes research 12, studies on the organization of the Roman imperial border on the Rhine and Danube).

- ^ Rudolf Fellmann: Principia - staff building . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 31), Limesmuseum, Aalen 1983, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Zsolt Visy: The Pannonian Limes in Hungary . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-8062-0488-8 , p. 103.