Masada

| Masada | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Masada with the Dead Sea in the background |

|

| Contracting State (s): |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | iii, iv, vi |

| Surface: | 276 ha |

| Reference No .: | 1040 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 2001 (session 25) |

Situation in Israel |

Masada ( ancient Greek Μασάδα Masada , New Hebrew מצדה Metzada ) is an archaeological site in Israel . It is in the southern district . On a summit plateau on the edge of the Judean Desert , high above the Dead Sea , Herod had a palace fortress built. This royal refuge was completed around 15 BC. The architecture is partly traditional (Eastern-Hellenistic), partly based on the model of Roman villas . Herod offered his guests a special attraction with water luxury in the form of a thermal bath and a swimming pool.

Around 70 years later, during the Jewish War , many people used Masada as an escape rock. Archaeological findings show an everyday life characterized by poverty and a high fluctuation of the population living here. For years it was possible to come and go, until the Legio X Fretensis under Flavius Silva appeared in front of Masada in 73 or 74 AD, enclosed the fortress with a rampart and raised a siege ramp. After the portrayal of Flavius Josephus , the Romans finally managed to tear a breach in the outer wall. In a hopeless situation, the commander of Masada, Eleazar ben Jaʾir , had convinced all rebels to commit suicide with their wives and children. As is customary in ancient historical works, Josephus wrote these speeches for Eleazar. It is questionable whether the taking of Masada took place as Josephus describes it. The archaeological findings cannot be combined with the statements of Josephus without tension. But there is also no consensus on an alternative scenario.

In 1838, Edward Robinson and Eli Smith identified the ruins, called es-Sebbe in Arabic , with the ancient desert fortress described by Josephus. Since the 1920s, Masada gained symbolic importance for the Jewish inhabitants of Palestine : In Yitzhak Lamdan's verse Masada (1927), the desert fortress stands metaphorically for the Zionist project. During the Second World War, numerous groups undertook the difficult ascent to the summit plateau, an experience which, together with Lamdan's epic, contributed to the formation of a "Masada myth". The metaphorical meaning of Masada changed against the background of the establishment of the state and the further history of Israel. From 1963 to 1965, Yigael Yadin directed large-scale excavations on the summit plateau. He published a popular account of the life of the Zealots on Masada and the Roman conquest, in which he harmonized the archaeological findings with the account of Josephus.

In 1966 Table Mountain and the surrounding area with the Roman siege complex were declared an Israeli National Park . On December 14, 2001, UNESCO added Masada to the World Heritage List .

Surname

The ancient name of the place was Aramaic in the texts of Wadi Murabbaʿat מצדא Metzadaʾ and in Hebrew in the copper scroll of Qumran המצד haMetzad ; Both terms have the same meaning: "Mountain height, mountain fortress." The table mountain of Masada corresponds in an almost ideal way to the requirements of a refuge rock to which the population could withdraw in times of need. So it's very aptly named. Josephus transcribed the Aramaic name into Greek, Metzadaʾ became Masada .

Geology and geographical location

The archaeological site Masada is located on the plateau of an isolated table mountain made of dolomite of the Upper Cretaceous ( Cenomanium - Turonium ) on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert . It belongs to the Heʿetekim cliffs that border the Dead Sea valley on the west side. As a relatively young, little eroded eyrie on the edge of a tectonic plate , it is also geologically interesting. It has approximately the area of a diamond , the diagonals measure about 600 m in length and 300 m in width. The summit plateau rises about 450 m above the west bank of the Dead Sea. On the west side, however, the difference in altitude is only 75 m.

Two wadis arise on the lowest level of the Judean Desert and run from the west towards the table mountain of Masada. Wadi Nimre (Nachal Ben Jaʾir) bypasses the mountain in the north, Wadi Sebbe (Nachal Metzada) in the south; They then form, "falling suddenly over a cataract, a 200 m deep gorge with almost vertical walls." While Table Mountain is difficult to access from the east side, its west side is less steep. There it is connected to the heights of the Judean Desert by an approximately 200 m wide saddle between Wadi Nimre and Wadi Sebbe .

The historical traffic connections to Masada originated during the Jewish war; In 1932 Adolf Schulten stated: “The roads that Silva built back then to stock everything necessary for the siege are still available and passable today.” This network of paths is therefore presented in more detail as part of the Roman siege complex.

flora

Archaeobotanists identified plants in the range of finds of Masada that still grow here today: the shrubs Anabasis articulata , Hammada salicornica and Zygophyllum dumosum could serve as fuel for the ancient inhabitants. Acacias ( Acacia raddiana , Acacia tortilis ) and tamarisks ( Tamarix ) grew in the neighboring wadis then as now . Cattail ( Typha ), reed ( Phragmites ) and giant reed ( Arundo ) found in ancient times in the area of the bathing facilities on the summit plateau the necessary moisture.

fauna

Various animal species from the Judean Desert can be found in and around Masada, particularly birds. This includes the tristram star ( Onychognathus tristramii ), which is used to tourists in Masada and can be observed up close. The approximately sparrow-sized blacktail ( Oenanthe melanura ) shows a similar behavior . There are also corvids such as the bristle raven ( Corvus rhipidurus ) and the desert raven ( Corvus ruficollis ) in the Masada National Park .

Specimens of the Nubian ibex ( Capra nubiana ) are also commonly seen in Masada National Park.

Ancient source texts

With the exception of brief notes from Strabo and Pliny the Elder , two writings by Flavius Josephus are the sources for the story of Masada: Jewish antiquities and the Jewish war . For the time of Herod, Josephus was able to use the lost universal history of Nikolaos of Damascus . Josephus was in Rome while Masada was besieged and conquered. So he is not an eyewitness to these events, but may have seen reports from Roman commanders.

Josephus describes the buildings of Masada not in connection with the government of Herod, but as the scene of the Jewish war. It is unclear whether he knew the place firsthand. Josephus is nowhere known to show that there were two great palaces. According to Achim Lichtenberger , Josephus' description of the palace is vague and is reminiscent of a typical Hellenistic ruler's palace, a four-towered castle similar to Antonia Castle in Jerusalem. The description of the interior is also imprecise. Josephus writes of monolithic columns and stone paving of walls and floors; what he have meant is , are the stuccoed columns and marble inlays imitative wall decoration of the 2nd Pompeian style ( architectural style ). There are similar set pieces in other descriptions of the palace by Josephus. Ehud Netzer considers that Josephus saw the North Palace from a distance - and from below, so that the terrace walls appeared to him like towers. Whether the Jerusalem upper class had any knowledge of the buildings on the plateau in which Josephus participated as a member of this group also depends on how Herod used Masada. If he was doing government business here, it can be assumed if it was a private retreat for emergencies, less so.

history

Masada in the time of the Hasmoneans

According to Josephus, the Hasmonean high priest Jonathan was the first to have a fortress ( ancient Greek φρούριον phroúrion ) built on the Masada plateau . This Jonathan is mostly identified with Alexander Jannäus (103–76 BC). The pre-Eodian development of Masada emerges from the information given by Josephus and is also not in question, but there is no archaeological evidence for this so far.

In the unstable political situation after the murder of Herod's father Antipater (42 BC) an opponent occupied Masada, the strongest Hasmonean fortress. Herod granted him free retreat and thus took Masada. In 40 BC The Parthians conquered Judea and installed Antigonos Mattathias as high priest. Herod managed to escape to Idumea . There he left his family on Masada under the protection of a military unit of 800 men. Herod asked the King of the Nabataeans and the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra VII for help in vain . He then traveled to Rome by sea. Protected by Mark Antony , he received the support of the Senate . This gave him the title "King of Judea" and commissioned him to wage war against the Parthians and Mattathias. Meanwhile, Mattathias besieged Masada. The crew of the fortress was temporarily in a threatening position due to water shortages, which was defused by heavy rain. The dependence of Masada on cisterns becomes clear here. Herod returned to Judea, horrified Masada and successfully carried on the war.

Palace fortress of Herod

Herod was a Jewish client king of Rome. In his government activities he sought to combine various factors:

- He wanted to be perceived as an observant Jew. Therefore he had the temple rebuilt and expanded the Jewish shrines in Hebron ( Machpelah ) and Mamre . He complied with the Torah's ban on images when decorating his palaces and with the motifs on his coins .

- He showed himself to be a Hellenistic ruler: victorious and rich. Wealth could be represented well through construction projects, victory in the context of the Pax Romana only to a limited extent. Palace fortresses like Masada underline the defensive strength of Herod.

- He maintained good relations with Rome and communicated to his subjects that the power of Rome was behind him. Typical Roman villa architecture or thermal baths fit into this picture, even if the naming of major building projects as Antonia (after Marcus Antonius) and Caesarea were certainly a clearer message for contemporaries.

According to Josephus, Herod had Masada expanded as his private refuge ( ancient Greek ὑποφυγή hypophygḗ ), both in the event of an uprising of his own population and against a threat from the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII. After the battle of Actium , Herod went to Rhodes to pay his respects to the victor, Octavian . He previously placed part of his family on Masada; apparently a safe and befitting residence had now arisen there. After Herod's death, Masada fell to Herod Archelaus . He was deposed in 6 AD. After that a Roman garrison was probably stationed in Masada.

Scene of the Jewish War

In midsummer of AD 66, in the early stages of the Jewish War , a group of Zealots led by Menahem took Masada in a coup. They killed the Roman soldiers and distributed the stored weapons. Menahem and his retinue went to Jerusalem. There he became the leader of one of the civil war factions, but was defeated in the internal power struggle of the Zealots and was killed. Those who were able to save themselves from their people fled to Masada. In the following, Josephus consistently refers to this group as Sicarians . It is not a self-designation, but a term coined by the Roman authorities for extremists who had carried out attacks on Jewish collaborators in the run-up to the war (Latin sicarii from sica “dagger”). With the withdrawal to Masada, this group had taken itself out of the game and no longer had any influence on the decisive battles for Jerusalem. The Sicarians did not fight against the Roman army, but against other Jews - this is how Josephus portrays it.

The fortress was in command of Menahem's nephew, Eleazar ben Jaʾir . In the winter of 67/68, the sicarians from Masada attacked neighboring towns and murdered hundreds of Jews during the Passover festival in the spring of 68 in En Gedi . Josephus could have fabricated this information in order to show the occupation of Masada in the worst possible light; but such forays made sense to fill Masada's magazines with groceries. Josephus also mentions that Simon bar Giora , one of the leaders of the Zealots, was temporarily ousted from Jerusalem and found refuge with his people in Masada. After that, Bar Giora's zealots were active with forays into southern Judaea and Idumea. "These episodes highlight the strong fluctuation among the residents of Masada," comments Jodi Magness.

The war was decided after the fall of Jerusalem (70 AD). The fact that Masada became the target of an elaborate Roman military campaign years later was possibly due to the economic attractiveness of the balsam plantations of En Gedi. Masada was suitable as a base for forays into the area; Guy Stiebel suspects such a threat En Gedis could not be tolerated. In 73/74 AD Masada was besieged by the Legio X Fretensis and almost 4,000 auxiliary soldiers under the command of Flavius Silva . Dating is controversial in research. Werner Eck argued with good reason as early as 1969 that Flavius Silva had become governor of Judea in March 73 AD at the earliest and that Masada could not have been conquered in April 73. Therefore, the conquest of Masada must be dated to the spring of next year, April 74 AD. The appointment in April goes back to Josephus, Jewish War 7.401: The month of Xanthikos corresponds roughly to March / April. In contrast to other sieges during the Jewish War, Josephus in a striking way fails to report effective resistance from the defenders of Masada. However, their numerical inferiority made it impossible for Masada's defenders to make a sortie, the most effective means of countering the construction of a siege ramp.

According to Josephus, the siege ramp was 100 m high after its completion and was given a solid stone paving on an area of 25 × 25 m. A metal-clad, 30 m high siege tower was placed on top. The siege tower crew attacked targets in the fortress with projectiles and ballistae, forcing the defenders to withdraw from the outer wall. Now the Romans attacked this casemate wall directly with a battering ram and tore a breach into it. The defenders had built a wall of wood and earth behind it; Flavius Silva had this construction set on fire. The fortress was now defenseless, and the Romans, according to Josephus, withdrew until the next morning.

Shaye Cohen notes that Josephus, like any ancient historian, was free to translate the facts known to him into literature. The fact that the soldiers withdrew until the next morning is incomprehensible. Falling darkness was no obstacle to taking a fortress. But only through the possibly fake order to withdraw, Eleazar ben Jaʾir was given the opportunity to make two speeches, of which only the second really convinced his colleagues: suicide saves women from rape Children from Slavery. The treasures and the fortress should be set on fire beforehand, because the Romans would be "annoyed" if they could not steal any booty. Until morning there was time for the unanimous and organized destruction and killing actions in the portrayal of Josephus, in which the Sicarians, according to Josephus, saw “the test of their bravery ( ancient Greek ἀνδρεία andreía ) and their right will ( ancient Greek εὐβουλία euboulía )”.

“So they quickly threw all the property into a heap and set a fire on him. By lot they then chose ten men from among their number; they should be everyone else's murderers. Then everyone lay down next to his already stretched out family members, the wife and the children, wrapped his arms around them and, finally, willingly offered their throats to the men who had to perform the unhappy service. They all murdered without hesitation; then they determined the same law of lot for themselves among themselves. ... But the lonely last one overlooked the crowd all around. ... When he realized that all had been killed, he set fires in many places around the palace. Then he thrust the sword all the way through his body with concentrated strength and collapsed next to his own. "

960 people died; two women and five children who had gone into hiding survived and witnessed what happened. (The talk of collective suicide is common, but imprecise: only the last person committed suicide in the strict sense, and the death of women and children was decided by others.) The next morning the legionaries made their way through the burning ruins. They toured the palace and the bodies. Flavius Silva left a garrison in Masada and returned to Caesarea Maritima . So much for Josephus' report.

Cohen suggests a different, chaotic scenario: some families committed suicide, some Sicarians set fire to the buildings in several places, some stood up to fight, others went into hiding. The advancing legionaries killed who they found. Josephus, now in Rome, improvised his story with the information available to him. Eleazar's speeches play a central role. In addition to the above-mentioned motives for suicide, they contain other considerations that were obviously important to Josephus. “He wanted Eleazar, as the leader of the Sicarii, to assume the full blame for the war, that he recognized his policies as wrong, that he confessed that he had sinned along with his people, and that he expressed the blasphemous thought that God had not only punished his people but discarded. Convicted by their own words, Eleazar and his people then kill themselves and thus stand for the fate of all who imitate them and resist Rome. "

Byzantine period

Early Christian monasticism originated in Egypt. In the Judean Desert, however, a monastic landscape of its own soon developed, influenced on the one hand by its proximity to Egypt and on the other hand by pilgrimages to Jerusalem and Bethlehem. In the 6th century there were about 65 monasteries in the Judean Desert. The ruins of Herodian desert palaces were also inhabited by monks: in Herodion their settlement was called Castellium, in Masada it was probably Marda .

“[It is said that Euthymius of Melitene around 420] took the route into the southern desert along the Dead Sea and came to a high mountain called Marda ... which was separated from the other mountains. There he found a collapsed pool of water, repaired it, and stayed there. He fed on the plants he found ... was the first to build a church in this place ... and an altar in it. "

In the 7th century, under Islamic rule, the number of monasteries decreased, although some have survived to the present day, including the monastery of St. George in Wadi Qelt and Mar Saba in the Kidron Valley .

Research history

Identification of the place, cartography and first soundings

Edward Robinson and Eli Smith toured Palestine and neighboring countries from 1837–1838 with the aim of identifying biblical and ancient places. From En Gedi on May 11, 1838, the two of them looked at a pyramid-shaped cliff with a flattened peak rising steeply above the Dead Sea. There were ruins there, which the Arabs called es-sebbe . With the telescope , Robinson recognized “a building on its NW part and also traces of other buildings further east.” At first they thought the complex was an old monastery. Then they consulted Josephus' description of Masada and identified es-Sebbe with this ancient site.

The missionary Samuel W. Wolcott and the painter William J. Tipping climbed the high plateau in 1842 and provided the first close-up descriptions and drawings of the ruins. Other explorers followed their example. Before the archaeological excavations began, the ruins of the Byzantine church were the eye-catcher on the summit plateau. Since it was called ḳasr (castle) in Arabic , several travelers identified it with the palace of Herod; it was measured accordingly carefully. Louis Félicien de Saulcy removed parts of the floor mosaic from the nave in 1851; they are in the Louvre today . As part of the Survey of Western Palestine , Claude Reignier Conder drew up exact plans of the site in 1875.

Alfred von Domaszewski and Rudolf Ernst Brünnow traveled to the Middle East in 1897/98 to collect information about the Roman province of Arabia Petraea . In February 1897 they visited Masada. Domaszewski began with an inventory of the Roman siege complex; but there was only enough time to examine one of the camps. In March 1932, Adolf Schulten spent a month investigating Masada, but only made two ascent to the summit plateau and devoted the rest of the time to the Roman siege technique. Schulten was a specialist in this field; he had previously excavated the Roman camps of Numantia (Spain).

In 1955 and 1956 the Israel Exploration Society , the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Israel Antiquities Administration carried out the first site surveys in 10 days each with a team of experts led by Nahman Avigad . On the one hand, detailed maps of the plateau were created in the short time, on the other hand the foundations of a round building on the central terrace of the north palace were excavated.

Archaeological research

A team led by Yigael Yadin carried out extensive excavations on the summit plateau of Masada in two campaigns from October 1963 to May 1964 and from November 1964 to April 1965. Following this, Yadin published a popular book on Masada and a preliminary scientific report. A final report was not published until Yadin's death in 1984. Yadin's associates Gideon Foerster and Ehud Netzer , Hebrew University , were then given the task of reviewing and publishing the material; since 1989 eight volumes of the final report have appeared in print.

Between 1995 and 2000, Ehud Netzer and Guy Stiebel, Hebrew University, carried out small excavations on the summit plateau in connection with the tourist development. One of their most spectacular finds is a fragment of an amphora with the inscription “Herod, King of Judea.” Also in 1995, a team carried out archaeological studies of the Roman camps and the siege ramp (Gideon Foerster, Benjamin Arubas and Haim Goldfus, Hebrew University; Jodi Magness, Tufts University ). In February 2017, Guy Stiebel, now Tel Aviv University , led a new excavation on the summit plateau. Among other things, the cistern of the Byzantine monastic community near the church was exposed.

Ancient buildings

| Location map | |

|---|---|

|

1st east gate; 2. Zealot quarters; 3. Byzantine monk cells; 4. Eastern cistern; 5. Zealot quarters; 6. Jewish ritual bath; 7. South Gate; 8. Zealot quarters; 9. South cistern; 10. South Bastion; 11. swimming pool; 12. Small Palace; 13. Round Columbarium Tower; 14. Byzantine mosaic workshop; 15. Small Palace; 16. Small Palace; 17. Basin with steps. West Palace : 18th commercial wing ; 19. West palace of the first construction phase, later stately wing; 20. Storage rooms; 21. Administration wing. 22. tannery; 23. Byzantine West Gate; 24. Columbarium Towers; 25. Synagogue; 26. Byzantine Church; 27. Villa; 28. Villa; 29. earthfill; 30. Headquarters; 31st tower; 32. Administration building; 33rd gate; 34. Magazines; 35. Great thermal baths; 36. North gate (water gate). North Palace : 37th Upper Terrace; 38. Middle terrace; 39. Lower terrace. A. Location of the Hebrew Jesus Sirach Scroll; B. Throne Room; C. Polychrome mosaic; D. Break in the casemate wall; E. Münzhort; F. Location of the ostraka (lots); G. Bad; Location of skeletons. |

Approaches to Masada

When Herod began to develop Masada into a palace fortress, access was probably only via two mule tracks, one from the west and the other (the so-called snake path) from the east. The western approach could be older and pre-Eodian.

In times of peace there was then a well-developed path on the west side to the palaces of Herod; it was largely covered by the Roman siege ramp. The upper part of the Herodian Way was still there until a severe earthquake in 1927. So the travelers of the 19th century climbed the Roman siege ramp and used this old path for the last stretch until it crashed in 1927. Yigael Yadin's excavation team had made camp at the foot of the mountain. The archaeologists and volunteers climbed the Roman ramp to the excavation site on the plateau; Pioneers of the Israel Defense Forces had built a staircase to replace the broken ancient path.

The snake path already described by Josephus was connected to a route that led to En Gedi and the Dead Sea, which in ancient times was traveled by boats.

Water supply

The annual precipitation on the slopes of the southern Jordan Valley is a long-term average of 50–100 mm; it falls from November to March. Since no source could be used, the water supply for the people on the Masada plateau mainly depended on cisterns. The ancient engineers faced two challenges: to transfer water from the rainy winter months to the rainless summer months and also to compensate for years with low winter rainfall. The most important resource these engineers used were the two wadis that led past the Masada Table Mountain: Wadi Nimre (Nachal Ben Jaʾir) in the north, Wadi Sebbe (Nachal Metzada) in the south. When they filled with water from winter rains, it was dammed up by dams that no longer exist today and channeled into two groups of large cisterns on the north-western flank of the mountain. These cisterns had been knocked out of the surrounding dolomite rock, whereby the excavation could also be used as building material. There were 12 storage cisterns on the side of the mountain plastered with hydraulic mortar ; a staircase led to the bottom. The upper group of cisterns was accessed by a path that ended at the north gate ( 36 ); the path that connected the lower group of cisterns led to the snake path, which rose in a zigzag shape on the east side of the mountain and ended at the east gate ( 1 ). A tower halfway up the slope protected this water system. On the mule tracks, pack animals carried leather bags of water, which had been filled from the cisterns on the slope, onto the plateau. There the water was poured into the basins and cisterns distributed over the entire complex. A total of 48,000 m 3 of water could be stored on Masada , which means that 1000 residents would have had 130 liters of water per person available daily for a year. This effective storage enabled Herod and his guests to enjoy water luxury in the form of swimming pools and thermal baths.

Buildings from the time of Herod

According to Ehud Netzer, after analyzing the stratigraphy and the architecture "with the greatest plausibility, on an experimental basis", three development phases can be distinguished:

- First phase of construction, around 35 BC Chr .: Inner area of the West Palace ( 19a ), three centrally located small palaces ( 12 , 15 , 16 ); in the south of the plateau a large swimming pool ( 11 ); two administration and supply buildings in the north ( 27 , 32 ). At that time, the complex was only protected by its location on Table Mountain and three so-called columbarium towers ( 13 , 24 ). Swimming pools and columbarium towers are elements that can also be found in the Hasmonean palace complex in Jericho . So Herod had it built here in the traditional style of Jewish kings. This impression is reinforced by the similarity of the room layout with the palace complex in Jericho.

- Second phase of construction, around 25 BC. Chr .: Completion of the main buildings: the north palace ( 37 - 39 ), laid out on three levels, including thermal baths ( 35 ) and stores ( 34 ) as well as the west palace ( 18 - 21 ), which was enlarged by extensions. An acropolis had now emerged in the north of the plateau . A gatehouse ( 36 ) controlled the path that led to cisterns on the northwest flank of the mountain. The assignment of the two palaces is not clear. It would be plausible that the north palace was Herod's private living area, while the west palace was used for official receptions and the accommodation of guests. The architecture would then also express a distancing of the ruler from the other inhabitants of the plateau. But the north palace with its unusual architecture was in any case suited to impress guests. The West Palace, which is in the older Hasmonean building tradition, should perhaps "appeal to a different group of people than the exquisite North Palace with its Roman-Hellenistic architectural forms."

- Third phase of construction, around 15 BC Chr .: Only now the entire plateau was enclosed with a casemate wall and the north palace was clearly isolated from the other buildings on the plateau. At this point Herod's rule was established; But that means: this is primarily a prestige building, the military importance of the casemate wall was not a priority.

Netzer places Masada in an overall picture of Herodian building in the region, especially the buildings in nearby Jericho can be compared. Achim Lichtenberger takes over the three construction phases of Masada proposed by Netzer and, based on observations on the architecture of the north palace, carefully dates the second construction phase to the time after Herod's meeting with Octavian (30 BC). The considerable effort that was made here, and the influence of Roman architecture, go at a time when Herod had secured his rule and established stable relations with Rome.

West palace

The great west palace had a floor area of about 4000 m 2 . In terms of building typology, he placed himself in a Hasmonean or Eastern Hellenistic tradition. Characteristic for this are the seclusion of the facility from the outside, the multifunctionality of the rooms (living, representation, service, magazine) and the artistic execution of the floor mosaic and the wall decoration.

The stately wing of the West Palace ( 19a ) was created in the first phase of construction and at that time was the ruler's only living area. He had at least one other floor. This residential and representative building had a floor area of around 28 m × 23.5 - 24.5 m (the western outer wall deviates somewhat from the rectangular complex for unknown reasons). A visitor entered this palace from the north side through a series of two guard rooms and then stood in an open courtyard (12 × 10.5 m). Opposite, on the south side, he saw a reception room (7 × 6.7 m), which opened up as a covered portico in the shape of a distylon in antis to the inner courtyard. The Ionic columns and pilasters were stuccoed and painted black and red. The shady location made the stay here quite pleasant, so that Netzer suspects that Herod usually received his guests here, and that the so-called throne room B, which is adjacent to the east, was only avoided in extreme weather conditions . Three passages connected these two representative rooms. Four soil pits in the back corner of the room of B interpreted Yadin's team as hard shoulders of a throne or canopy . According to Gideon Foerster and Ehud Netzer, however, it is unlikely that the king would receive his guests sitting in a corner. They interpret the footprints as a reference to a display table, as it was in Hellenistic palaces. Luxurious tableware, for example, was presented on such a table to be admired by the guests. The throne room had another entrance on its north side. Here included a small hallway to the next room to a (possibly ceremonial for storing clothes) and the so-called mosaic room C resulted. The function of the mosaic room (8.0 × 5.0 m), which was divided into two by a distylon in antis, was obviously that of a passage room: from here one could get into the inner courtyard, exit the palace through a rear exit or climb the stairs to the upper floor . But the splendid furnishings suggest that the mosaic room could also fulfill representative tasks. On the opposite, western side of the central courtyard, there were living rooms, the function of which cannot be determined, while the rooms on the north side of the courtyard were partly utility rooms, partly (in the northeast corner) formed a small bathing complex in the “Greek-Jewish style”. The room layout of the upper floor can be accessed; there were probably bedrooms here.

In the second construction phase, two utility wings were added to the West Palace. The farm wing ( 18 ), which is larger with a floor area of 35 × 22 m , and a wing with around 20 rooms around an inner courtyard, was added to the north. Two units could only be entered through a guard room and were therefore suitable for storing valuable objects. Workshops could have been located in other rooms of this wing. The second commercial wing ( 21 ), measuring 20 × 15 m, was located to the northwest of the stately residential wing and was most likely used for food preparation. The main entrance to the “old” West Palace now ran between the two new economic wings.

In the third construction phase, the West Palace continued to grow and now received four storage rooms ( 20 ) in the west and south . Three were 27 m long, the fourth, 56 m long, is the largest storage room in Masada. In the north-western corner of the palace, two wings were added, one an utility wing, perhaps the central kitchen, the other a living wing ( 19b ), perhaps for the palace guard officer.

Three small palaces

The three small palaces 12 , 15 , 16 come from the first construction phase and show a similar room layout as the royal wing of the West Palace ( 19a ), which was built at the same time . They all have an open inner courtyard with a shady, open reception room on the south side with distylon in antis , which is adjoined by a closed reception room in the southeast corner. What all these palace complexes of the first construction phase have in common is that there are no windows that could provide views of the landscape. Their distribution on the plateau also seems to follow topographical conditions alone; the palaces appear isolated and do not form an ensemble. The three small palaces were probably designed for members of the royal family as well as for guests who Herod received on Masada.

Swimming pool

With their extensive pools, the Hasmonean palace complexes were innovative. The Winter Palace in Jericho had seven of them, some of which were in use at the same time. Located in a desert landscape, just filling the basin was a technical challenge, a demonstration of the abundance of water. Herod followed this tradition. For Masada, a swimming pool ( 11 ) from the first construction phase should be mentioned here. The Herodian and Hasmonean pools are very similar: the depth varies between 2.5 to 3 m, one side of the pool has a staircase, a kind of bench leads all the way around the edge of the pool, and this is plastered with hydraulic mortar.

Columbarium Towers

Three columbarium towers , two with a rectangular floor plan ( 24 ), one round ( 13 ), belong to the first construction phase. They stand out through numerous niches in the walls of the ground floor. Yadin tried an experiment to find out whether it was an ancient dovecote. Since a domestic pigeon did not accept the ancient columbarium, Yadin took the view that the ashes of deceased non-Jews who belonged to Herod's entourage had been buried in the niches. Yadin's hypothesis is no longer supported today because much more is known about pigeon breeding, which has been practiced on a large scale in Judea and especially in the Jerusalem area since the Hellenistic period. In Masada, keeping pigeons contributed to the palace kitchen. The three towers connected pigeon keeping on the ground floor and guard rooms on the upper floor.

North palace

The north end of the Masada plateau resembles a ship's keel and naturally has three terraces arranged in steps. The middle terrace is 18 m lower than the summit plateau, the lower terrace is another 12 m lower or 30 m lower than the summit plateau. Herod's architects took advantage of this fact and created a spectacular palace complex that opens up to the surrounding landscape. Located on the north side of the mountain, it was a pleasant, shady stay in the desert climate. This shows the Roman side of Herodian architecture. A multi-level axial villa architecture can also be found in suburban palaces and sea villas of the Roman upper class and the imperial family.

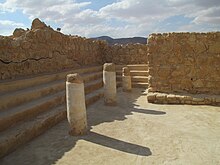

In order to be able to use the lower terrace ( 39 ) for a palace building, a 12 m high retaining wall had to be installed at the northeast corner. The buildings on this terrace are best preserved. A rectangular hall (10.3 m × 9.0 m) with surrounding colonnades allowed panoramic views of the surrounding desert landscape. You can imagine it as a covered triclinium . The limestone columns and half-columns with fluting made of stucco follow the Corinthian order and stand on raised wall plinths that alternate with windows. If necessary these windows could be closed with wooden shutters. The spaces between the half-columns were decorated with wall paintings of the 2nd Pompeian style. Foerster points out that this banquet hall is in the tradition of Alexandrian palace architecture. On the east side you came to a small bathhouse G , on the west side the stairwell and on this way up to the middle terrace ( 38 ).

The buildings on the middle terrace are poorly preserved. Ehud Netzer interprets two concentric circles of foundations as tholos , or a hall with an upper arcade and a surrounding ring hall. The outer circle has a diameter of about 15 m; the distance between the two circles is about 3 m.If you trust Herod that he wanted to provide his non-Jewish guests with a place of worship, you can understand the rotunda as a shrine to Aphrodite. Alternatively, it can also be a Belvedere . Gideon Foerster refers to round dining rooms in Vergina and Pella . The south adjoining exedra with five niches is interpreted as a library; Netzer considers this to be impossible, since the room was exposed to the weather. Decorative objects may have been exhibited in the niches.

On the upper terrace ( 37 ), the residents of Masada clearly found late Republican-Imperial villa architecture: in the center a large oecus (11.5 m × 7.6 m), from which three private rooms ( cubicula ) each led off on the west and east sides . They have geometric black and white floor mosaics ( opus sectile ) and wall paintings in the 2nd Pompeian style. From the south-east one entered the palace through a vestibule and then on the left hand side there was access to the Oecus and on the opposite side a wide view of the landscape. A porch on a semicircular floor plan (diameter 9 m) was used for this. Only small remains have been preserved, especially fallen column drums. This was probably a pergola with a columned portico, a kind of viewing platform that may have included a small garden.

To the south, adjacent to the upper terrace of the palace complex, there was a large thermal baths in Roman style as well as a warehouse building with a conspicuously narrow rectangular floor plan, and finally an administration building and barracks. There was thus a closed development at the northern end of the summit plateau.

Big thermal baths

The large thermal baths ( 35 ) were structurally separated from the north palace. Therefore, anyone wishing to visit this luxurious complex did not have to enter the North Palace, the seclusion of which was apparently important. The entrance was in the form of a palaestra (18 × 8.4 m), which was surrounded on three sides by colonnades . On its north side there was an exedra and next to it a basin into which steps led down. It can be interpreted as natatio or as mikveh . The actual thermal bath area had a floor area of 17.5 × 11.5 m and was divided into the changing room ( apodyterion ), the cold water basin ( frigidarium ), into which steps led, the painted and tiled warm room ( tepidarium ) and finally the largest room (6.8 × 6.6 m), the hot water and hot air system ( caldarium ). This room was domed, while the other rooms had flat ceilings. The caldarium had two niches. In one, rectangular, the bather found a quartzite water basin. In the other, on a semicircular floor plan, there was probably a marble hot water basin (labrum) . This is no longer available. Herod's thermal baths differed from their Roman model in the design of the frigidarium. A basin with steps leading down to it took up most of the room. Netzer assumes that this basin was also used as a ritual immersion bath (mikveh). Remnants of the rich interior with floor mosaics and frescoes have been preserved. With the exception of the palaestra, the floor mosaics were later replaced by opus sectile floors. The technical systems and ancillary rooms necessary for the operation of a thermal bath have been preserved ( hypocaust ) or can be recognized as imprints of lead pipes in the findings.

Casemate wall

With the exception of the Acropolis (north palace, large thermal baths, warehouse building), the 1.290 km long casemate wall with its 27 towers enclosed the entire plateau. It was erected in the third construction phase and included the gatehouses and two columbarium towers from the first construction phase. The casemate wall consists of a 1.4 m wide outer wall and an inner wall 4 m away from it. The approximately 70 casemates thus have a standardized width and the length (up to 35 m) varies. Their height is estimated at 4 to 5 m. The individual casemate rooms could be used in many ways, as storage for supplies or as living quarters for soldiers and staff. Several casemates were connected to one another in the western wall, possibly a residential unit, e.g. B. for a commander. The 27 towers were incorporated into the casemate wall at a distance of about 40 m. At the southern end of the plateau the casemate wall was reinforced by a bastion ( 10 ). This had several floors with 5 rooms each lined up along a corridor; a spiral staircase opened the presumably 3 or 4 floors.

Buildings and conversions from the time of the Jewish War

"Based on archeology, we would conclude that a single Roman legion was besieging a fairly small number of Jews, including families, who for some reason had taken refuge on the top of this desert fortress," said Atkinson. As a rule, however, the archaeological evidence is not considered in isolation, but combined with Josephus' report.

Living quarters and workshops

The people who fled to Masada in the Jewish War not only furnished the rooms of the casemate wall as apartments by inserting partition walls, they built groups of mud huts that leaned against the wall or other buildings ( 2 , 5 , 8 ). The thin walls of these huts could only support light roofs made of branches or textiles. The archaeological traces of everyday life are diverse: ovens and storage niches, remains of textiles, leather, baskets, glassware, bronze utensils, etc. were found in large numbers in these living areas, as well as hundreds of coins and several fragments of scrolls. Apparently the towers were often used as workshops; a workshop ( 22 ) that the excavators interpreted as a tannery is now identified as a laundry.

In the mosaic room of the West Palace ( C ) and an adjoining room, the Zealots set up a workshop for arrowheads. Perhaps they wanted to use the pools in the adjacent bathing wing to cool the forged iron. Over 200 arrowheads of the Roman type have been found here.

Synagogue / assembly room

In the north-western area of the casemate wall there is an installation ( 25 ), the function of which cannot be clearly determined in Herodian times. It may have been a stable because the archaeologists found several layers of dung on the ground. Yadin suspected that the building was already being used as a synagogue at the time of Herod and was only used as a stable by the garrison stationed on Masada before the Jewish War. Renovations took place during the Jewish War. The building has a floor area of 15 × 12 m; five columns in two rows carried the ceiling. The Zealots tore down a partition and added plastered benches all around the walls. In the northern corner they separated a chamber (5.7 × 3.5 m). Typical features by which ancient synagogues can be recognized are missing here: the niche for the Torah shrine, Jewish symbols as decorative elements, the orientation towards Jerusalem. Jodi Magness suggests that the term synagogue be understood here in its original sense of the word (“gathering”). It is undoubtedly a meeting room.

The chamber wasn't screed like the rest of the building, but had a floor made of rammed earth. Here Yadin's team came across pits from the time of the siege. This contained parchment remains from biblical writings. That was an additional argument for identifying the building as a synagogue. The excavators identified the chamber with a geniza in which sacred texts that had become unusable were deposited. Genizot have only been attested since the Middle Ages. Such repositories for sacred texts became necessary because restoration of damaged scrolls was considered possible only to a limited extent. The example of Qumran shows that in ancient times different beliefs prevailed and damaged rolls were mended in a way that would have been unacceptable in the Middle Ages. Seen in this way, ancient Jews did not need a geniza.

Ritual immersion baths (mikvehs)

“Pools of water with steps leading down to the bottom function as a bath in this region and epoch.” However, it is difficult to determine on the basis of archaeological criteria whether bathing was of religious significance for the users at the time. The Talmudic Mikwaot lays down precise rules for a ritual immersion bath, but they cannot be applied to all mikvahs from the 1st century AD. In particular, the requirement of “running water” seems to have been interpreted differently in this early period. It is also conceivable that suitable pools, for example in the frigidarium of the Masada thermal baths, were used for ritual immersion baths as required, without losing their everyday function as a bath. Yadin identified two mikvahs. Depending on the criteria used, 16 to 21 pools on the Masada site are interpreted as mikvehs today.

The difficulty of identifying a mikveh can be illustrated by building 17 (photo), “a mighty swimming pool in an asymmetrical shape, with stairs and dressing niches.” Yigael Yadin and Hanan Eshel dated the complex to the Herodian period and interpreted it as Swimming pool that was available to guests in the West Palace. Against this interpretation, the fact that typical features of Herodian bathing pools, such as a rectangular floor plan, are missing. Ehud Netzer , Ronny Reich , Asher Grossberg and Yonatan Adler, on the other hand, interpret 17 as a mikveh from the time of the Jewish War. It may have been used by Essenes who settled in the West Palace and / or in Palace 16 and created a small Essen district on the grounds of Masada. Against this interpretation, the fact that a water basin of this size could not be filled with "running water" (not even with the help of a roof construction for collecting rainwater) and filling with cistern water would have contradicted the later rules for a mikveh.

When Yigael Yadin and his team dug in Masada in the 1960s, little was known archaeologically about ancient mikvahs. For the next few decades, the mikvahs of Masada shaped the image that research made of these ancient immersion baths. A key scene was the inspection of an immersion bath on Masada by the Orthodox Rabbi David Muntzberg. It was an installation in the southern casemate wall ( 6 ): The plunge pool was mainly filled with cistern water, which could be mixed with rainwater from a neighboring reservoir. Because of this rainwater supply line, the entire contents of the immersion basin were regarded as "flowing water". Muntzberg examined the installation and declared it a mikveh, which meets the highest standards. Yadin assumed that modern rabbinical authorities in this area applied the same standards that applied in ancient times. This formed his image that the defenders of Masada were Orthodox Jews. Ritual baths and the synagogue document that religion was of great importance to the defenders of Masada. As fighters against Roman invaders they were a role model for the citizens of Israel, as traditional Jews they could be identification figures for Jews worldwide.

Roman siege complex

The buildings of the Roman military during the siege of Masada are among the best preserved of their kind. Neither vegetation nor overbuilding changed the structures, only winter torrents damaged some of the walls. Adolf Schulten was enthusiastic about the state of preservation in which the camps presented themselves to him in 1932: "The clavicula at the south gate of Camp F has been preserved in its old height, and one could still camp today on some of the triclines built into the barracks ."

The Roman tactic otherwise practiced during sieges of enclosing the enemy with a wall and then starving them to death was not promising in the case of Masada. Because there were large supplies of drinking water and food on the plateau, while the besiegers had to bring their own supplies relatively laboriously. Their strategy, therefore, was aimed at shortening the siege; the siege ramp was used for this.

Stage roads

The first measure taken by the Roman army was to upgrade the roads to Hebron and En Gedi, as the transport of food and drinking water was a significant logistical problem for the besiegers. That could be done in a week, possibly by a vanguard. Schulten described the Roman stage roads, which at the beginning of the 20th century were clearly visible in the terrain as 5 to 6 m wide strips:

- The 4 km long road to the Dead Sea began at the Porta Praetoria of bearing B . There was shipping traffic to En Gedi on the Dead Sea.

- The road to Hebron (34 km) began behind the Roman wall, then climbed down into Wadi Sejal , in two bends up to the plateau "and is still the road from here to Hebron today ."

- The Masada – En Gedi – Herodium – Jerusalem road (16 km) is believed to date from the time of Herod, but was expanded during the Roman siege: It began at Camp D , ran at the foot of the valley wall as a well-built road with a substructure; after 1800 m a road branched off to the right, which led through the beach level to En Gedi. In accordance with its special importance, it was given a small fort for protection.

Wall and warehouse

The approx. 2 m wide blockade wall made of unprocessed field stones has been preserved over a length of approx. 3.5 km. He blocked all regions that would have enabled the Masada garrison to break out or escape. Basically, the siege wall was superfluous, because even without a wall there was no unnoticed escape from the summit plateau. Roth sees this as an employment measure for those parts of the Legion that could not be used to build the ramp. Wall and ramp were therefore built parallel and not, as Josephus suggests, one after the other.

Jonathan Roth adopts Schulten's calculations that 8,000 Roman soldiers were involved in the siege, as well as around 2,000 military slaves. Roth also estimates that around 3,000 Jewish forced laborers had to bring the earth for the filling up of the ramp; they were probably housed in a walled area at the foot of the ramp.

Eight camps (designation: A to H ), also made of quarry stone without mortar, are located near the siege wall or are integrated into it. Usually their floor plan is a parallelogram . What is striking is the small area and the resulting dense interior development of the warehouse. Inside the camp you can still see walls up to 50 cm high, which, according to Schulten, are the outer walls of legionnaires' barracks and not markings for the tent sites. They were on average around 3.5 × 2.5 m, but this size does not seem to have been standardized. More recent surveys, aerial photographs and excavations supplemented this picture: the leather legionnaire's tents were stretched over the walls and secured with iron pegs. The horseshoe-shaped structures within these barracks were triclines, with sleeping places for eight soldiers per barrack, no berths for eating. With these triclines you gave away some of the already scarce space, but probably accepted it because it was easier to get to your own, only 45 cm wide sleeping place without disturbing your companions. The cooking facilities were in front of the entrance to the barracks and can often still be seen as a circle in the floor.

Camp F was the headquarters of the Roman army during the siege. The outer walls measure 168 × 136 m; within this camp there is a smaller camp ( F2 ) in the southwest corner ; this is likely to be the location of a Roman garrison after the conquest of Masada. Material from the larger camp was used to build camp F2 , so that of all things the Roman headquarters is comparatively poorly preserved. The final coin dates from the year 112 AD. The entrances to the two larger camps F and B were protected by extensions (clavicula) . After Schulten, half of the Legio X Fretensis was housed in these two camps.

Through camps A , B and C on the east side of Masada, Flavius Silva forced his opponent Eleazar Ben Jaʾir to deploy some of the defenders to protect the east gate and thus to withdraw from the west side, where the siege ramp was built. These three camps also blocked the Wadi Sebbe (Nachal Metzada) and thus the most promising escape route. Towers, namely massive stone base, had the bearing A and C . Guns were probably positioned on it.

The stock E and F were exposed to the artillery of the defenders, if one possessed. But the Romans did not build their camps within range of enemy artillery, stresses Andrew Holley. If the Zealots had artillery at all, the Romans probably viewed them only as a nuisance, not a danger.

Siege ramp

For the ramp, Flavius Silva's engineers made use of a natural rock ridge that ended just 13 m below the summit plateau. The ramp landed on him. The building material provided the environment; Forced laborers had to get it here. However, the legionaries themselves built the ramp to prevent sabotage. Tamarisk and date palm woods were used to hold the stone and earth packs together. Essentially, the ramp was made of rough-hewn limestone blocks that were broken nearby. According to Josephus, the legionaries built a mighty stone platform at the top of the ramp on which they placed the metal-clad siege tower . This was their base for the attack with projectiles and ballistae , while a battering ram finally brought the fortress wall to collapse. In their investigations of the Roman siege ramp, Benjamin Arubas and Haim Goldfus found no traces of the stone platform and no findings that would have confirmed a violent ballista fire in this segment, such as that which occurred e.g. B. from Gamla and Jotfata is known. According to Arubas and Goldfus, the fact that a piece of the casemate wall has broken out, which is usually interpreted as the work of the Roman besiegers, can also have other reasons, e.g. B. Construction work in Byzantine times. Arubas and Goldfus believe that the siege ramp has suffered little erosion since it was built in antiquity, and that it was never much higher than it is now. But that means that it was not completed enough to serve its purpose. They therefore believe that the last phase of the Roman siege of Masada took a different course from that described by Josephus, which one must remain open. Various authors have contradicted Arubas and Goldfus here. Gwyn Davies argues that the stone paving could have been buried in the strong earthquake in 1927, and even if one conceded that the siege ramp ended at about its current level, 13 m below the plateau, one placed on it would have been 30 m higher Siege tower clearly towers above the casemate wall.

Holley points out a depot of ballista balls in casemate room L 1038. It is unlikely that a ballista of the defenders was positioned here. But the point is strategically very favorable to attack the legionnaires with archers and slingshots while building the siege ramp. That is why the Roman ballistae took this section of the wall under heavy fire. According to Holley, the bullets struck in this area were collected in one place (depot) as part of the clean-up work after the capture of Masada.

A second siege ramp?

During the Yadin's excavations, a large pile of earth was found against the outer wall of the Acropolis in the north of the plateau. Volunteers from the youth organization Gadna were only busy for eleven months to remove this low-funded embankment. Hillel Geva suggests that this 20 m long and 15 m wide hill ( 29 ), about 600–750 m³ of earth mixed with architectural fragments, was another Roman siege ramp. Since the third Herodian construction phase, the acropolis with the north palace was an independent unit, separate from the rest of the building on the summit. Geva suspects that some rebels holed up there after the Roman army had entered the fortress and continued to offer resistance, so that the soldiers had to build a wide ramp to penetrate into the Acropolis. If so, the collective suicide reported by Josephus did not take place.

Byzantine monastic settlement

After the abandonment of the Roman fort in the early 2nd century, Masada was uninhabited until a Christian monastic community of around 15 to 20 people settled on the plateau in the 5th century. The only building that the monks rebuilt was the church with its extensions. All other buildings of the Byzantine period were built using the building material of the ruins of 73/74 AD.

The well-preserved Byzantine gate ( 23 ) consists of an outer gate, a courtyard and an inner gate. It was built in place of a Herodian west gate. From there a path leads to the center of the Lavra , the church complex: The church ( 26 ) consists of the nave (10.3 × 7.7 m) with an apse and a narthex (4.8 × 2.4 m). The walls are partially preserved almost up to the ridge height. They were plastered with smoothed mortar into which Roman ceramic shards were imprinted in such a way that they form geometric patterns. In the apse there is a central window with a round arch. The church has two extensions on the north side, including a room on a square floor plan (3.6 × 3.6 m) with a mosaic floor (photo). The central panel is well preserved and shows 16 medallions framed by a braided ribbon, with geometric shapes, plants, fruits and a basket with twelve loaves of bread. On the east side of the church, the monks built a courtyard (18 × 20 m), which they enclosed with a wall. The utility wing of the Lavra (kitchen and refectory ) was apparently housed in a section of the casemate wall, about 50 m west of the church. Stone tables and Byzantine storage vessels stood here. This area was also surrounded by a wall by the monks. The church complex and this economic tract were the areas of the lavra in which the community life of the monks took place. The rest of the time they spent as hermits in their cells, which were set up some distance apart. A total of 13 monk cells in the form of small stone buildings and caves can be found in several places on the plateau, for example:

- on the wall of the caldarium in the great thermal baths,

- in the entrance area of the West Palace,

- in a former cistern,

- in the round columbarium tower.

The workshop of the mosaic layer ( 14 ) can be localized by the quantities of mosaic stones available there.

Single finds

The desert climate and the remoteness of the rock plateau have preserved a rich spectrum of objects from ancient everyday culture. The individual finds can come from the Herodian period, from the years of the Jewish War or from the Byzantine period; this cannot be determined more precisely in every case. Most of the findings, however, belong to the destruction horizon of the Roman occupation in 73/74. After that, clean-up work took place on the plateau. The legionaries, or, less likely, the Byzantine monks, poured rubble and rubbish into excavated pits and some casemates; two examples:

- The casemate tower ( 22 ) used as a laundry was completely, ie 4 to 5 m high, filled with rubble; These included pieces of leather, ceramics, a papyrus fragment with Greek and Latin names, and 34 coins.

- Casemate L 1039, near the synagogue ( 25 ), was furnished with an oven and silo for residential purposes. In addition, a pile of ballista balls was found there and a thick layer of rubble with wicker baskets, remains of textile, coins (including silver shekels), seven fragments of biblical and extra-biblical scrolls, 18 Latin and 4 Greek papyri. The silver shekels lay together and must have been hidden in the wall as a small hoard.

Literary texts

Among the ancient manuscript finds in the Dead Sea area, the texts of Qumran and Masada have a special position: firstly, they come from the same period (the documents from Wadi Daliyeh are earlier, the finds from Nachal Zeʾelim , Nachal Chever , Nachal Mischmar , Wadi Sdeir , Wadi Murabbaʿat and Ketef Jericho are to be dated later), secondly, they are literary texts. Therefore it is discussed whether there is a connection between the two text corpora of Qumran and Masada.

- The remains of 13 scrolls with texts from the Hebrew Bible were found at various points on the summit plateau . They are of great importance for the textual history of the Bible because they provide insights into what the Hebrew text looked like before the unifying work of the Masoretes . The manuscript MasPs b , for example, is interesting because it belonged to a book of psalms that ended with Psalm 150 , while other textual traditions ( Septuagint , but also 11Q5 from Qumran) know more than 150 psalms. The biblical book of Ezekiel has a complicated genesis; Changes were made to the text until the Hellenistic period. The Ezekiel scroll fragment that was found in the synagogue of Masada ( 25 ) is very fragmentary, but covers several chapters and testifies to the same chapter order as the later Masoretic text. This is not a matter of course, because the papyrus 967 from the Egyptian Aphroditopolis, written around AD 200, has a different chapter arrangement. Overall, the biblical texts of Masada are very close to the later normative text of the Hebrew Bible, and according to Emanuel Tov this speaks for a Jewish community with close ties to Jerusalem, where the proto-Masoretic text (until the destruction of the city in 70) was in in a special way.

- In the rubble of a casemate ( A ) lay the remains of a scroll from the book Jesus Sirach .

- Among the text finds in casemate L 1039 was a copy of each of the Sabbath sacrificial songs , the Apocryphon of Joshua (uncertain) and the book of jubilees . Copies of these texts can also be found under the Dead Sea Scrolls . Emanuel Tov suspects that Essenes fled to Masada when the Roman army destroyed Qumran and brought these texts with them. However, it is also argued the other way round: the fact that nine copies of the Sabbath sacrificial songs were found in Qumran and one copy in Masada may indicate that the authors, despite linguistic features that point to Qumran, “are not necessarily sociologically located in the Jachad ”. Originally, the Sabbath sacrificial songs could come from the priestly liturgy in the Jerusalem temple. Even more so, the very popular anniversary book was not read exclusively in Qumran.

- The papyrus fragment Mas 721 lat (maximum dimensions: 16 × 8 cm) is inscribed on both sides with a Latin hexameter in a practiced handwriting. The sentence on the front comes from the Aeneid : "Anna, dream images frighten me, make me doubt and waver." If the writing was around the same time as the conquest of Masada, it is one of the earliest Virgil manuscripts. The past participle titubantia is clearly legible from the incompletely preserved hexameter on the reverse . However, the verse cannot be assigned within the well-known Latin poetry. The papyrus comes from the luggage of a soldier of the 10th Legion. Hannah M. Cotton and Joseph Geiger suggest in their final report that the writer wanted to express his emotions in the face of taking Masada through a literary quote. As a literary text, Mas 721 lat stands out from the group of Latin papyri. Other papyri allow insights into the everyday life of the Roman military, e.g. For example, a document listing amounts that a legionnaire named Gaius Messius paid for barley and clothing, among other things, that went from his wages, or a list of medical supplies such as bandages and oil.

Ostraka

Over 700 ostracas have been found on the Masada site. Most of them only have a single letter. Others are labeled with a name. These ostracas contribute to the paleography of the Hebrew script . According to Jodi Magness, the ostraka were primarily used to organize the distribution of food from the magazines. With ostracas, but also with corresponding inscriptions on vessels, one could also indicate whether the contents were cultically pure or impure, tithed or not tenthed. An ostracon apparently names an otherwise unknown son of the high priest Ananias . His name was ʿAḳavia, apparently staying with the rebels on Masada and certifying the cultic purity of goods there. Kenneth Atkinson concludes from the presence of a member of the Jerusalem priestly aristocracy that the leaders on Masada were a group of priests and Josephus obscured this - after all, he was a priest himself.

To the west of the Great Thermal Baths ( F ) there were traces of severe devastation, including more than 250 ostraca. Yadin designated twelve of the ostracas, which had been described by the same person, as lots and brought them in connection with Josephus' report that ten (not twelve) people had been drawn to kill the rest. One ostracon bears the name Ben Jaʾir, so probably referred to the commander of the fortress. Joseph Naveh , who published the ostraka in the final report, did not repeat this interpretation by Yadin. It is not possible to determine which tasks or rations were assigned with the help of name ostraca.

Presence of Essenes and Samaritans

Both Essenes and Samaritans are said to have stayed in Masada. The strongest argument for the presence of Essenes are literary text finds that can be compared to the Dead Sea Scrolls . Biblical texts, the Sirach book or the jubilee book may have been brought to Masada by fleeing Essenes from Qumran; This is relatively likely in the case of a copy of the Sabbath sacrificial songs found in Masada, which is very popular in Qumran. But it can hardly be ruled out that a non-Essener brought this scroll with him to Qumran.

Spinning whorls are very common in the Masada finds with 384 specimens. Spinning was a typical activity for women in ancient times. As expected, spindle whorls were often found in the context of Zealot accommodation, but it was striking that there were some buildings clearly used as living space in which spindle whorls were almost completely absent. Ronny Reich suspects that celibate Essenes lived here who also used a nearby mikveh ( 17 ) , architecturally reminiscent of Qumran . An additional argument is the distribution of found coins, combined with the assumption that the Essenes had a common treasury and therefore hardly lost coins individually. From this, Reich derives the hypothesis that an effective administration arranged the accommodation of the refugees on Masada, assigning families, individually arrived people and Essenes with their special religious practice to separate living areas. Jodi Magness objects that the distribution of the coins in the finds from Qumran shows no abnormalities, but what would be expected if they are characteristic of the hypothetical Essen district of Masada. The uneven distribution of spindle whorls and coins in the living areas of Masada is interesting, but since these are small, light objects, one cannot draw such far-reaching conclusions from it.

From casemate L 1039 comes a piece of papyrus that contained a fragmentary text in paleo-Hebrew script . This script was (and is) used by Samaritans for their sacred texts. The text contained the phrase "Mount Garizim"; the spelling הרגריזים without word separation is typical for Samaritan texts. Shemaryahu Talmon suspected that this papyrus belonged to a Samaritan who had fled to Masada. He therefore assumed that the population of Masada had been very heterogeneous during the Jewish War: alongside Zealots, whom he classified as “mainstream” in religious terms, dissidents such as Essenes and Samaritans. Hanan Eshel , in contrast, interpreted the text as anti-Samaritan poetry expressing joy over the destruction of the Samaritan temple on Mount Garizim. The text is so fragmentary that a decision on this issue is impossible. Although Talmon's papyrus fragment was given the suggestive name "Masada papyrus with paleo-Hebrew text of Samaritan origin" (Mas pap paleoText of Samaritan Origin) in the final report , Emanuel Tov considers the small fragment to be insufficient to draw historical or other conclusions from it.

Presence of women

The fact that there were numerous Jewish families living in Masada was emphasized by Josephus in connection with the collective suicide. Ronny Reich's spindle whorl study provided confirmation of this. The finds also include objects that belonged to women, e.g. B. several hairnets and cosmetics. A certain Joseph, son of Naqsan, resident of Masada, issued his wife Mariam, daughter of Jonathan, a letter of divorce (Get), which gave her the freedom to marry another Jew. The document is dated "Year 6" of the Jewish uprising - in year 5 Jerusalem fell. Mariam left the place before the Roman siege began. Her divorce letter was found among the documents in Wadi Murabbaʿat . Together with other evidence, this text finding points to the fluctuation in the population of Masada: "Until the beginning of the siege, the refugees came and went."

Nutritional situation

Josephus praised the magazines Herod had put on Masada, and archeology has confirmed him on this point. The finds include around 4,500 ceramic vessels, many of them Herodian, but almost all of them in use during the final phase of the Jewish War. Red-coated tableware and amphorae come from the context of the Herodian residence, but are rare. The bulk of the pottery is of local Judean production: storage vessels and saucepans. The fact that supplies remained in the magazines to the end contradicts Josephus' account and supports those who consider his report on the capture of Masada to be inaccurate.

37 vessels bear inscriptions indicating their contents, including over half of them were containers for dried figs. Berries or olives, fish, dough, meat and herbs were also mentioned. The finds contained pomegranate, olives and figs. Horticulture should have been possible to a modest extent in Masada, and some sheep and goats could have been kept. But that should not give the impression of rich nutrition, because these goods were probably only available to a few. According to Magness, the menu of the Zealot families can be imagined as follows: bread dipped in olive oil, bean mash or meatless lentil stew. The supplies from the stacks of Masada have been examined by archaeologists. They were heavily infested with parasites, especially the dried fruits.

As in the elegant Herodian quarters in Jerusalem and in Qumran , products of the local stone-cutting trade were also found in Masada. They look like large limestone mugs (31 complete specimens, 110 fragments). Since stone vessels, unlike ceramics, do not accept ritual impurity, they were popular with the wealthy, B. observed a high standard of ritual purity as a priest. Yadin's excavation team also found vessels made of sun-dried clay and animal manure in which grain and dried fruits were stored. According to the Mishnah, these vessels also do not accept impurity. Jodi Magness assumes, however, that vessels made of clay and dung were often used by poor Jews and non-Jews, but are only found in archaeological excavations under favorable conditions. Even during the siege of Masada one could make these unfired vessels on the spot; According to Magness, this need not be an indication of a high level of interest in cultic purity among the poor.

Skeleton finds

Yadin's team found remains of human bones in two places. They were buried on July 7, 1969 for religious reasons.

- In 1963 skeletal remains were found in a basin ( G ) on the lower level of the North Palace, which were assigned to three individuals, a woman, a man and a boy. Since the age of the woman was estimated to be a maximum of 18 years and that of the boy was estimated at around 12 years, it was agreed at the team meeting that the two adults could be a couple, but the boy not the son of that woman. In his publications in 1966, 1971 (contribution to the Encyclopaedia Judaica ) and a scientific lecture in 1973, Yadin asserted with increasing certainty that he was dealing with a "very important commander", his wife and their child. He killed his wife and child, set the palace on fire and then committed suicide. Nachman Ben-Yehuda points out that this version only appears to fit Josephus' account. Because after Josephus the last fighter does not kill his family, but the other nine drawn. The killing of over 900 people may have taken place at the West Palace, but there is no room for it in the North Palace.

- Yadin's team found human bones in a small cave on the southern slope below the southern gate ( 7 ). The exploration of this cave was directed by Yoram Tsafrir . Nicu Haas, the anthropologist of the excavation, identified the remains of 15 men, six women and four children as well as an embryo. So neither Roman soldiers nor Byzantine monks could be buried here, only Zealots, Yadin concluded. “Did your comrades bring you to this cave during the siege? It's hard to believe. So there is only the possibility that the irreverent Roman soldiers threw them there after the victory. ”In 1982 Shaye Cohen considered it unlikely that the soldiers would remove hundreds of bodies of their opponents by (probably) removing them over the wall into the depths threw, but selected 25 corpses and dragged them into a hard-to-reach cave, where they themselves were in danger of falling: "This is not disrespectful, this is foolish." Instead, he suggested that a group of Jews hid in the cave, there was discovered by the legionaries and killed on the spot.

From an anthropological point of view, Joseph Zias has raised objections to Yadin's interpretation of the skeletal finds since the 1990s. No skeletal remains of a woman were found in the basin of the North Palace, only her braids, which were cut off close to her scalp during her lifetime. Zias suspects that the two male dead were members of the Roman garrison who were killed by the insurgents in 66. The woman was left alive as a prisoner of war, but her hair was cut short, in accordance with the Torah laws of war ( Dtn 21.10–14 EU ) and their interpretation in the temple scroll . The skeletons in the basin of the North Palace may have been dragged to this place by hyenas . Noticeably, a lot of protein-rich bones were missing here.

The findings in the cave could be the bones of Romans. It was not until 1982 that Yadin announced to the public that pig bones had also been found at this point. A pig sacrifice at the funeral was common among Romans and Greeks in ancient times. It is widely documented in Europe and Cyprus. In the same interview in 1982, Yadin also stated that because of the pork bones he had reservations about assigning the skeletal finds from the cave to the Jewish defenders. However, rabbinical authorities had a keen interest in burying the bones and suggested that Masada's defenders kept pigs to clear up a waste problem. Zias doubts the number of 25 (or 24) dead after the brief report of the anthropologist Haas to Yadin became known. According to this, only 220 bones were found in total; assuming 24 deaths, 96% of the bones would be lost, which is a very high value in view of the conservation conditions in the desert climate of Masada. Then photos became known which Tsafrir had taken during the archaeological investigation of the cave. They show that there were three graves: two primary burials of individual individuals and one grave in which 5 to 6 individuals were buried together. Zias' conclusion is that the pig sacrifice clearly speaks for a Greek or Roman burial. The dead are Roman soldiers or civilians who were in Masada either before or after the Jewish War.

Ultimately, according to Jodi Magness, the lack of skeletons of the defenders is neither evidence nor refutation of the report of the end of Masada that Josephus wrote.

Reception history

Origin of the Masada myth

The events of Masada did not appear in rabbinic literature . The author of Josippon , a medieval Hebrew retelling of Josephus' Jewish War , has the defenders first kill their wives and children, but then face the Roman legionaries in a final battle instead of committing suicide. Although Josippon's version actually complies with the Masada myth, it has been little received over the centuries and also in the State of Israel. The Israeli Masada myth is based on Flavius Josephus. However, he made the following typical changes to this ancient text:

- It is not mentioned that the defenders of Masada were sicarians, in modern terms a kind of terrorist.

- The siege of Masada is extended to two to three years, although it only lasted a few months.

- The defenders are portrayed as heroic fighters, although Josephus does not write anything about them.

- Their suicide is interpreted as an act of self-liberation, which embodies the will to survive of the Jewish people.

Yitzhak Lamdan: Masada (1927)