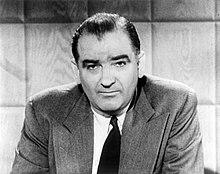

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond "Joe" McCarthy (born November 14, 1908 in Grand Chute , Wisconsin , † May 2, 1957 in Bethesda , Maryland ) was an American politician . He was a member of the Republican Party and was best known for his campaign against the alleged infiltration of the United States government by communists . The so-called McCarthy era of the early 1950s is named after him , in which anti-communist conspiracy theories and denunciations determined the political climate in the USA.

Life

Beginnings

McCarthy was born the fifth of seven children to strict Catholic farmers. To help support the family, he dropped out of school early in 1922 and ran a small poultry farm and a grocery store, among other things. He made up his high school graduation in just one year in 1928 and began law school at Marquette University . From 1935 he worked as a lawyer, in 1939 he was elected District Judge of Wisconsin . In 1942 he volunteered for action in World War II and was employed as an intelligence officer with the rank of lieutenant in the US Air Force . At home he stylized himself through skillful publicity and manipulation as the experienced rear gunner of a bomber "Tail-Gunner Joe", including an alleged wounding in battle with (fake) later commendation ; in fact, he had a party accident with the company. In serious combat missions he was hardly involved with personal risk due to his service position; He was only "gunner" in the Marine Corps on Bougainville in the hinterland that was already militarily secured, where he caused civil damage.

Upon his return, McCarthy used his fabricated image as a war hero in the Wisconsin Republican primaries : "Wisconsin needs a tail-gunner" was the claim of his campaign. His rival candidate, Senator Robert M. La Follette junior , who had not been able to take part in the World War due to age, could do little to counter this. The fact that La Follette had represented the Wisconsin Progressive Party from 1934 to 1944 and had only recently returned to the Republicans cost him further sympathy among the party people. McCarthy, who also spread that La Follette was a war profiteer , narrowly won the primaries. In November 1946, he then prevailed with 61.2% of the vote against his Democratic rival Howard McMurray and entered the Senate .

The first years in Washington

The 80th Congress of the United States (1947-1948) was dominated by the Republicans, who for the first time since 1933 had a majority in both chambers. As the youngest Senator, McCarthy quickly understood how to develop his image as a man with a great political future through numerous legislative initiatives as well as through excellent contacts to the press (including columnist Jack Anderson , later his bitter opponent) and to the top people of the Republican Party. The conservative Saturday Evening Post described him in August 1947 as a "notable newcomer to the Senate."

Politically, McCarthy harmonized on most questions with the conservative wing of the Republicans around their Senate leader Robert Taft . The topics to which he devoted himself in particular were determined by the concerns of the immediate post-war period: He campaigned for a quick end to the rationing of sugar and was committed to overcoming the precarious housing situation in large parts of the United States. Political opponents later accused him of having acted as a lobbyist in both fields, on the sugar issue for Pepsi-Cola and on the housing issue for a construction company from Ohio.

McCarthy came out early on with harsh anti-communist remarks. As early as 1947, he spoke out in favor of a ban on the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) and declared in July of the same year:

"We have been at war with Russia for some time , and Russia is about to win this war faster than we did at the end of the last war - so we are about to lose it."

McCarthy had made few friends in Washington with his gruff and unscrupulous manner. When the legislative term drew to a close in 1950, he was still missing a topic that would secure his popularity and re-election.

McCarthy's anti-communist campaign

Beginning

McCarthy began his campaign against the alleged infiltration of the government apparatus by communists in early 1950. Before the Republican Women's Club in Wheeling , West Virginia , he declared on February 9, 1950 that he had a list of 205 people, including the Democratic Foreign Minister Dean Acheson knows that they are "members of the Communist Party" and that they "still work in the State Department and have a say in its politics."

McCarthy was unable to substantiate his claim or give any specific names. In the following weeks he varied his information on the number of communists allegedly known to him in the civil service. In fact, such a list of names did not exist at all. Nevertheless, his statements met with a great response in the media and society. In the heated climate of the early Cold War, the indirect accusation that the incumbent US Secretary of State was covering up a communist infiltration of his ministry was sensational. Quite a few people were inclined to believe McCarthy because they could only explain the recent successes of the Communist camp, long regarded as hopelessly backward in scientific and military matters, through betrayal and covert collaboration by Americans.

It was only in September 1949 that the Soviet Union succeeded in successfully testing its own atom bomb ; At the beginning of February 1950, headlines about the confession of the German-British nuclear spy Klaus Fuchs confirmed the suspicion, which was rampant among the American public, that this development was made possible by betrayal of secrets from the West. In addition, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, marking the communist victory in the Chinese civil war , which for most Americans was both surprising and shocking . In East Asia, direct military clashes between the two political systems in the form of the Korean War were imminent.

The Wheeling speech and a few public appearances that followed made the previously largely unknown Senator from Wisconsin a sought-after interviewee within a few days. McCarthy's accusations have made headlines in many newspapers. As early as February 16, at one of his regular press conferences, President Harry S. Truman felt compelled to respond to McCarthy's repeated statements about communists in the State Department by stating that they contained "not a true word".

Asked by journalists to substantiate his allegations about communists at the State Department, McCarthy said at a press conference that he would present "detailed information" to the Senate if requested. As recently as February 1950, the Senate's Foreign Affairs Committee formed a relevant subcommittee, the Subcommittee on the Investigation of Loyalty of State Department Employees , better known as the Tydings Committee ( Tydings Committee) - named for its chairman, Democratic Senator Millard Tydings .

This subcommittee asked McCarthy to name the alleged communists in the State Department, but the Senator was unable to name a few suspicious officials. After five months of intensive investigation, the Tydings Committee came to the conclusion in a report published on July 17, 1950 that the people named by McCarthy were neither communists nor sympathetic to communism. McCarthy's allegations were "fraud and fraud committed in the US Senate and the American people." The report was signed by the three Democratic committee members but not by the two Republicans on the committee.

The Tydings Committee had given McCarthy the publicity he wanted. In November 1950 he was re-elected with 54.2% of the vote, his Democratic opponent Thomas E. Fairchild received 45.6%. McCarthy continued his campaign with undiminished vehemence. For example, he accused the well-known liberal columnist Drew Pearson of being a "Moscow-controlled character assassin" who had " hounded to death" former Secretary of Defense James V. Forrestal . Forrestal fell ill with severe depression in May 1949 from the sixteenth floor of the Naval Hospital in Bethesda. General George C. Marshall , the Democratic ex-foreign minister, was suspected by McCarthy in June 1951 of being in league with the communists, because in 1947 the later Nobel Peace Prize laureate had recommended that military aid for the national Chinese movement in Chiang Kai-shek be stopped. The, in his opinion, critical situation of the nation can only be explained with evil intentions, which are secretly pursued in the Truman government:

“It must be the result of a great conspiracy on such a scale that it makes every previous similar enterprise in human history seem ridiculously small. A conspiracy of shame, so sinister that its leaders, once exposed, deserve the curse of all righteous men forever. […] What can one say about this uninterrupted series of decisions and actions that contribute to a strategy of defeat? It cannot be attributed to incompetence [...] According to the laws of probability, at least a part [...] of the decisions would have to serve the interests of the country. "

During the 1952 election campaign, McCarthy concentrated his attacks on the Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson , from whose various relationships with former leftists he constructed a "guilt by association": Because his employees and acquaintances had not clearly positioned themselves against communism, Stevenson also supported himself guilty of communism. In January 1954 McCarthy finally defamed the entire term of office of the Democratic presidents Roosevelt and Truman since 1933 as "twenty years of high treason " in a press conference . Before defamation suits McCarthy was always protected in all these defamatory allegations because, as Senator political immunity enjoyed.

Chairman of the Government Operations Committee

In November 1952, the Republican Party candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower won the presidential election, with the Republicans gaining a slim majority in both houses of Congress . It is controversial whether McCarthy's campaign harmed or used them. Candidates who were closely associated with him performed worse than those who had kept a greater distance. The election results from Wisconsin also justify doubts about McCarthy's popularity at the time: In the Senator's home state, moderate Eisenhower was elected with 61% of the vote, while McCarthy himself only achieved 54% - seven percentage points less than six years earlier.

Nevertheless, the prevailing belief in the Republican Party was that the election success was at least partly due to the issue of anti-communism in general, and McCarthy in particular. As a gesture of thanks, McCarthy was offered the coveted position of chairman of a Senate committee in 1953 by the party leadership - but only for the rather insignificant Government Operations Committee (GOC). One goal was already to prevent the party friend, who was perceived as a possible compromise, from further political escapades and to involve him in routine parliamentary work where "he can do no harm", as the Republican majority leader Taft put it. McCarthy immediately countered public speculation that he would deal less with the communist threat to the United States in the future.

The task of the committee was a general control of state authorities and institutions. McCarthy's interest lay primarily in its 1952 established the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations) to make a tool to investigate the alleged instances of Communist infiltration of American society and thereby carry out high-profile convictions tests within the government. McCarthy's committee rivaled the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Justice Department over who got the most sensational headlines . Eisenhower's Vice President Richard Nixon had played a role in the HUAC from 1948 onwards, as McCarthy now imagined for himself in the GOC. The two committees were therefore often confused in public later on.

McCarthy took advantage of the new prerogatives of a committee chairman to set the course of the subcommittee almost single-handedly. He often surprised even its Republican members by not disclosing the subject of the deliberations to them until the day of a hearing. With some skill, he also quickly formed a powerful team by hiring young, ambitious lawyers such as Roy Cohn and Robert F. Kennedy . Within a few weeks McCarthy developed such a broad interest in the control of government and authorities that the spectacular and almost daily hearings of his subcommittee in the first half of 1953 have shaped his image to this day. Cohn soon became McCarthy's key collaborator and greatly influenced the course of these investigations.

A total of 653 witnesses were summoned during McCarthy's tenure as committee chairman whose civil rights were systematically violated. The hearings took on the character of court hearings , with the difference that at the end there was not a final conviction or an acquittal , but often the ruin of reputation and public standing, against which those concerned had no legal remedies . If they invoked their right under the 5th Amendment to refuse to testify, McCarthy revealed their names to the public and insulted them as "5th. Additional communists ” . In his role as prosecutor and judge in one person, he stylized himself as the guardian of American values , the protector from the "Red Danger". In doing so, he did not take into account the fact that the government was now provided by his own party. The minutes of the hearings held in private meetings (“Executive Sessions”) were not released to the public until 2003.

Hearings on the Voice of America and the US Information Service

In the first half of 1953 McCarthy made a name for himself with hearings on the International Information Administration (IIA). The agency with semi-autonomous status in the State Department employed around 10,000 people worldwide at the beginning of 1953 and had a budget of 100 million dollars. In addition to the Voice of America (VoA) radio service , which produced programs in 40 languages for a potential 300 million listeners, her area of responsibility was primarily the United States Information Service (USIS, also known as the Foreign Information Service , FIS). A wide variety of cultural, information and training programs were located in its almost 200 information centers abroad . The libraries of these institutions, also known as America Houses , were particularly popular . 41 information centers alone had been set up with a view to re- education in the Federal Republic of Germany and in West Berlin . Since 1945 it had become almost a tradition among Republicans in Congress to infiltrate the staff of VoA and USIS as communist and brand the whole program as one gigantic mismanagement - a leitmotif that was now taken up by McCarthy.

McCarthy declared on February 12, 1953 that his committee would deal with "mismanagement, subversion and nepotism" within the VoA with immediate effect . One of the allegations was that their program was too left-wing. This was evidenced by an IIA instruction, according to which works by the communist writer Howard Fast (Spartacus) could be used as demonstration material. McCarthy did not mention that the permission to use Fast's works had only been listed as an exceptional case in the context of an IIA directive actually aimed against communist authors and their works.

In the six weeks of hearings, some of which were televised, he extended his investigation to the entire Foreign Information Program of the United States Information Agency . He and his committee created a forum in which even extreme and defamatory accusations found attentive listeners. Instead of concentrating on investigating the waste of public money, as the party leadership had hoped and initially promised by McCarthy himself, McCarthy moved the alleged communist infiltration of American society into the center of the hearings. There were hardly any tangible disclosures: if the allegations raised by witnesses were of legal relevance, the actually responsible law enforcement authorities had investigated them long ago, sometimes years ago. Nevertheless, a number of VoA and other IIA employees were transferred or terminated as a result of the hearings. A VoA employee committed suicide, according to his testimony.

Since a witness testified during the VoA investigation that the works of no fewer than 75 Communist authors belonged to the holdings of USIS libraries, the work of the information centers abroad now came into McCarthy's field of fire. Thereupon Secretary of State John Foster Dulles issued the instruction on March 17, 1953: "Works by Communist authors are to be removed from all public libraries and information centers of the USIS," for which McCarthy publicly praised him. When defining what a “communist” is, the Foreign Ministry followed the guidelines of the senator: as a communist, whose books were to be subject to the ban, anyone who made the statement with reference to the Fifth Amendment was counted among others had denied a congressional committee.

After further investigation into the matter, McCarthy sent his coworkers Roy Cohn and G. David Schine on an inspection trip to Europe, where they were to convince themselves that the new, strict guidelines of the State Department had meanwhile been implemented. Because of the forced witnesses called McCarthy was held at a committee meeting that he was planning a " book burning " in the style of the Nazis , this trip was also referred to as "book-burning mission" ( "book-burning mission") in various media soon. Between April 4 and 18, 1953, it led to ten European cities (Paris, Bonn, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Munich, Vienna, Belgrade, Athens, Rome, London) and quickly developed into a comprehensive PR disaster McCarthy's associates were often portrayed as juvenile rowdies, especially in European newspapers and magazines. Cohn later wrote in his memoir:

“Unknowingly, David Schine and I gave McCarthy's enemies the opportunity to spread the myth that a pair of young, inexperienced clowns were blasting around Europe, ordering State Department officers and burning books, and messing everywhere they went spread and disrupted international relations. "

Because he had come across the crime novels The Maltese Falcon and The Skinny Man by Dashiell Hammett (who had previously invoked the Fifth Amendment to McCarthy's subcommittee) in the library of the Frankfurt America House , Cohn was able to triumphantly declare that the Dulles Guidelines were apparently not yet followed everywhere.

Conflict with the military

A little later, in the fall of 1953, McCarthy's committee began looking for Communists in the armed forces . The conflict arose over the case of a New York dentist who had been promoted to major and honorably discharged from the Army despite refusing to provide information about membership in subversive organizations. When the responsible brigadier general replied evasively in front of the committee, McCarthy yelled at him that he had the "mind of a five-year-old child" and was "unsuitable to wear a general's uniform" . These abuse led the United States Secretary of the Army , Robert T. Stevens , to forbid his officers from appearing before McCarthy's committee. However, he could not keep up with this instruction.

Instead, as McCarthy himself believed, the army began to pay back with the same coin the humiliation of one of its employees. In early 1954, she accused McCarthy and Cohn of using undue pressure to promote the military career of her former employee, David Schine. In March 1954 the magazine Time appeared with Cohn and Schine on the front page and the scornful subheading: "The army got its orders". "The army has its orders" . McCarthy immediately replied with a conspiracy theory : He was convinced that the army was holding his former employee as a "hostage" in order to prevent his committee from exposing other communists in their ranks.

To clear up the matter, a subcommittee was convened under the chairmanship of Republican Senator Karl Mundt, which began its work on March 22, 1954. After hearing 32 witnesses, including McCarthy and Cohn, the committee concluded that, while not the Senator, his closest associate, Cohn, had made “inappropriately emphatic or aggressive efforts” to advance Schine's career.

More important than this partial defeat was an exchange of words on June 9 between McCarthy and the lawyer Joseph Welch , who represented the army. The senator countered Welch's allegations with the counter-charge that a young man worked in his Boston office who was a member of a legal organization allegedly related to the CPUSA. In doing so, he violated the agreements that had been made before the hearing, which is why Welch, noticeably outraged by the casualness with which the senator ruined the career of an innocent man, cut him off:

“We don't want to continue murdering this fellow. (...) You have already done enough. Don't you have any sense of decency at all, sir? Do you have no sense of decency left? ”This criticism of his personal integrity, broadcast live on national television, earned McCarthy the first bad press. His public image of a gruff but honest fighter against subversion had begun to crack - public opinion was beginning to turn against him.

"See It Now"

The next attack came on October 20, 1953, when television journalist Edward R. Murrow's popular political magazine See It Now reported the dismissal of a US Air Force lieutenant accused of being a communist. Even more negative was the impact of See It Now's March 9, 1954 broadcast, which consisted almost entirely of footage of McCarthy spreading his usual accusations, accusing Democratic politicians of high treason, or berating witnesses on his investigative committee. McCarthy then appeared on the show himself, but his tried and tested method of intimidating opponents through suspicion had the opposite effect. (The story of this first politician's dismantling by the means of television journalism is told in George Clooney's 2005 film Good Night, and Good Luck .)

McCarthy and Eisenhower

In 1954, McCarthy also lost the president's support. Because the senator's conspiratorial tones were initially received positively by large parts of the population, Eisenhower had long let him go, even though President McCarthy's worldview by no means shared. During the election campaign, for example, he had inserted General Marshall's defense against McCarthy's suspicions in one of his speech manuscripts, but deleted the passage again at the request of his advisors.

In office Eisenhower moved more and more away from him, but without ever criticizing him publicly. The reason for this growing distance was that McCarthy continued to attack the government sharply, as if the Republicans were still in the opposition . In his diary, less than three weeks after taking office, President Eisenhower complained that it was apparently very difficult to convey to some Republicans "that they are now on the team that includes the White House ."

In public, Eisenhower warned McCarthy very carefully to exercise moderation. At a press conference, for example, he declared that Congress should use its right to investigate subversion with “self-restraint” and, above all, not damage the fundamental principle of the presumption of innocence. Significant, however, was his order not to provide McCarthy's committee with any documents from executive organs and not to allow them to testify under oath, as this could affect national security issues. This severely restricted the examination options.

McCarthy, on the other hand, continued his course against supposed communists, their supporters and belittlers. Out of disappointment with the trade policy towards communist China, he varied his campaign slogan in 1953 and spoke of "21 years of high treason", even suspected Eisenhower himself as a "disguised communist" and thus began a direct confrontation with the Eisenhower government.

Fall

There had been criticism of McCarthy's actions for some time in his own party. Senator Ralph Flanders, for example, is quoted as saying that McCarthy's anti-communism has striking parallels with Hitler's .

In late July 1954, Flanders moved in the Senate to reprimand McCarthy for improper conduct. A subcommittee, chaired by Senator Arthur Vivian Watkins , was set up to investigate the 46 allegations made against McCarthy. Most of these points were found to be inconclusive or not found in a majority among committee members. Two points remained: McCarthy had shown himself to be uncooperative with a Senate subcommittee in 1952, and, second, he had described the Watkins committee as the “unwitting maid” of the Communists. Based on the results of this review, after days of discussion, on December 2, 1954, a majority of 67-22 voted for McCarthy's conviction. Although he remained Senator of Wisconsin until his death, his position of power in the Senate was broken: he had to hand over the chairmanship of his committee to the Democrat John L. McClellan , who was to head the Government Operations Committee until 1972.

death

On April 28, 1957, McCarthy was admitted to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland . As on other similar occasions since the summer of 1956, when the senator had to go into inpatient treatment, his wife Jean again told reporters that the reason for the hospitalization was an old knee injury. Joseph McCarthy died on May 2, 1957 at 5:02 p.m. local time. While the death certificate stated "acute hepatitis , cause unknown" as the cause of death , his doctors declared (without wanting to provide further details) that McCarthy had suffered from a "non-infectious" liver disease for weeks. Media such as the news magazine Time then reported that the senator had died of cirrhosis of the liver . Today, alcoholism is widely believed to be the cause of McCarthy's health problems and death.

personality

McCarthy was considered a passionate politician, sometimes violent to ruthless nature. It is said that he was able to become extremely aggressive towards his political opponents. After a preview of the film Good Night, and Good Luck , the audience unanimously agreed that the actor who played the Senator had exaggerated greatly - even though the film only showed original footage by McCarthy. McCarthy also became violent at least once: in the cloakroom of a Washington club he is said to have slapped a journalist, according to another source he kicked him in the groin.

His critics, as well as some historians, attribute this lack of self-control to severe drinking problems . On the other hand, supporters of McCarthy claimed that he was by no means a Blue Cross , but also not an alcoholic; rather, the hepatitis was caused by an infection.

While he was still alive, his opponents spread the rumor that McCarthy and his close colleague Roy Cohn were homosexual . When a Las Vegas newspaper reported this on October 25, 1952, the Senator waived a libel suit and married his secretary Jeannie Kerr. The couple, who had no children until then, later adopted an infant from a New York orphanage. The allegations applied to Roy Cohn: he was a "closet homosexual" whose sexual orientation in his circle had been an open secret for decades; this only became known to the general public when Cohn died of AIDS in 1986 .

McCarthy and McCarthyism

Joseph McCarthy became a symbol of the anti-communist climate of the first post-war decade. For the so-called “Second Red Scare” - after the first in the years after the October Revolution - the terms McCarthy era or McCarthyism are also used. This first appeared on March 29, 1950 in a cartoon in the Washington Post . It shows Robert A. Taft and other leading Republican politicians guiding an elephant, the symbol of their party, to a rickety tower of dirt buckets, the top of which is labeled "McCarthyism". The headline echoes the elephant's fearful words: "Do you really think I should be on top of that?" McCarthy took this originally critical term and turned it into positive: "McCarthyism is Americanism with its sleeves rolled".

The senator's policies were typical of the persecution of alleged and actual communists in the United States in the early 1950s. In this early era of the Cold War, a conspiracy-theoretical, Manichean view of communism dominated, which saw in the Eastern Bloc the absolute evil that sought to destroy the values and the lifestyle of America. McCarthy can be seen as a good example of what Richard Hofstadter described in a much-cited 1964 essay as “the paranoid style in American politics”. From this perspective, constitutional principles seemed to him to be a dispensable luxury.

However, he was not the author of this persecution. There were public statements about an alleged infiltration of the State Department as early as 1947. The actual persecution began years before McCarthy's political crusade: at the latest when ten filmmakers were sentenced to prison terms in November 1947 because they were on theirs before the Committee on Un-American Activities of the House of Representatives constitutional rights of freedom of expression and the refusal to testify passed, it was clear that the wind had turned sociopolitically: Galt in the long years of the depression Great of capitalism have failed in many intellectuals to be manifestly and socialism as a more humane alternative that stood since the beginning of the Cold war basically everything left up to the left-wing liberal wing of the democrats under the general suspicion of subversion and espionage. The persecutions with which the American state sought to defend itself against this, such as the spectacular trials against Alger Hiss or Ethel and Julius Rosenberg , were also not due to McCarthy's initiative. Nonetheless, the anti-communist persecution carried out by the GOC, the HUAC and, last but not least, the FBI is inseparable from his name. The historian Ellen Schrecker therefore thinks:

“ McCarthyism outlasted McCarthy just as it had preceded it. […] Although in many ways he was more of a creature than the creator of the anti-communist crusade, McCarthy helped fuel it. Therefore it may not be entirely misleading that it is named after him. "

controversy

McCarthy was the subject of bitter controversy in his lifetime and continues to be today. In 2003, the right-wing conservative journalist Ann Coulter published her book Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism (in German, for example: High treason: Liberal faithlessness from the Cold War to the War on Terror ). In it she defends McCarthy, whom she admires, because the KGB , as has been known at least since the VENONA project deciphered the telegrams of its agents in the USA , actually had over 350 spies in the USA, including Harry Dexter White up to and including rose to higher positions in the Ministry of Finance . Therefore McCarthy's campaign was not a witch hunt, but justified, necessary and salutary.

This is countered by the fact that Coulter has no interest in historical truth; she only uses history to justify the neoconservatives and the renewed restriction of civil rights, for example through the USA PATRIOT Act . ( Liberal has been an effectively derogatory term in the American public since the Nixon period for the representatives of any non-revolutionary political position on the left the middle). There were certainly Soviet spies in the USA, but McCarthy's witch hunt was not directed against KGB agents, but against the far more harmless CPUSA and its alleged sympathizers. McCarthy did not succeed in identifying even a single communist spy within the USA.

The political scientist Harvey Klehr takes a mediating position: he also emphasizes that at the beginning of the 1950s the threat from communists and Soviet spies was real and greater than generally assumed. At the same time, however, he underlines that none of this offers any justification for McCarthy's excited and reckless behavior towards this threat:

“He remains a political hooligan who has harmed a large number of people. But his exaggerated and unfounded accusations also harmed the cause of anti-communism. [...] His foul accusations trivialized and weakened the well-founded allegations that existed. Real Soviet spies could present themselves as victims of McCarthyism. They found open, compassionate ears from not a few who were convinced that anyone who was dragged into espionage or communism must be innocent, because some innocent people had been charged. "

literature

- Jack Anderson, Ronald W. May: McCarthy. The Man, the Senator, the "Ism" . Beacon Press, Boston 1952. Dt. Edition: McCarthy, the Man, the Senator, McCarthyism . Arkos, Hamburg 1953.

- Edwin R. Bayley: Joe McCarthy and the Press . University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 1981, ISBN 0-299-08620-8 .

- William F. Buckley Jr., L. Brent Bozell: McCarthy and His Enemies. The Record and Its Meaning . Regnery, Chicago 1954. Dt. Edition: William F. Buckley: In the shadow of the Statue of Liberty . New West Publishing House, Munich 1954.

- Fred J. Cook: The Nightmare Decade. The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy . Random House, New York 1971, ISBN 0-394-46270-X .

- Donal F. Crosby, SJ: God, Church, and Flag. Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Catholic Church 1950–1957 . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1978, ISBN 0-8078-1312-5 .

- William Bragg Ewald Jr .: Who Killed Joe McCarthy? Simon & Schuster, New York 1984, ISBN 0-671-44946-X .

- Roberta Strauss fire light. Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism. The Hate That Haunts America . McGraw-Hill, New York 1972.

- Leslie Fiedler: McCarthy and the Intellectuals . In: Ders .: An End to Innocence. Essays on Culture and Politics . The Beacon Press, Boston 1955, pp. 46-87.

- Richard M. Fried: Men Against McCarthy . Columbia University Press, New York 1976, ISBN 0-231-03872-0 .

- Robert C. Goldston: The American Nightmare. Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Politics of Hate . Bobbs-Merrill Company, New York 1973, ISBN 0-672-51739-X .

- Robert Griffith: The Politics of Fear. Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate . 2nd edition. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1987, ISBN 0-87023-554-0 .

- Arthur Herman: Joseph McCarthy. Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator . Free Press, New York 1999, ISBN 0-684-83625-4 .

- Mark Landis: Joseph McCarthy. The Politics of Chaos . Susquehanna University Press, Selinsgrove 1987, ISBN 0-941664-19-8 .

- Earl Latham: The Communist Controversy in Washington. From the New Deal to McCarthy . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1966.

- David M. Oshinsky: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the American Labor Movement . University of Missouri Press, Columbia 1976, ISBN 0-8262-0188-1 .

- David M. Oshinsky: A Conspiracy So Immense. The World of Joe McCarthy . Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-515424-X .

- Thomas C. Reeves: The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, ISBN 0-8128-2337-0 .

- Michael Paul Rogin: The Intellectuals and McCarthy. The Radical Specter . MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London 1967.

- James Rorty, Moshe Decter: McCarthy and the Communists . Beacon Press, Voston 1954.

- Richard Rovere: Senator Joe McCarthy . Hartcourt Brace, New York 1959.

- Michael Straight: Trial By Television . Beacon Press, Boston 1954 (via the Army McCarthy Hearings).

- Thomas Lately: When Even Angels Wept. The Senator Joe McCarthy Affair. A story without a hero . Morrow and Co., New York 1973, ISBN 0-688-00148-3 .

- Arthur V. Watkins: Enough Rope. The Inside Story of the Censure of Senator Joe McCarthy by His Colleagues, the Controversial Hearings that Signaled the End of a Turbulent Career and a Fearsome Era in American Public Life . Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ 1969, ISBN 0-13-283101-5 .

- Tom Wicker: Shooting Star. The Brief Arc of Joe McCarthy . Harcourt, Orlando 2006, ISBN 0-15-101082-X .

Movies

- Citizen Cohn USA 1992, directed by Frank Pierson

- TV dramatization of the life of McCarthy's closest collaborator Roy Cohn, based on the biography of the journalist Nicholas von Hoffman of the same name . McCarthy is portrayed by Joe Don Baker and Cohn by James Woods .

- Good Night, and Good Luck USA 2005, by and with George Clooney

- The famous television presenter and journalist Edward Murrow and his editorial team bravely and publicly resist the defamation and propaganda of McCarthy.

- Insignificance - Die Verflixte Nacht GB 1985, directed by Nicolas Roeg , written by Terry Johnson

- Fictional documentary comedy based on a play by Terry Johnson about a purely hypothetical encounter between McCarthy and Albert Einstein , Marilyn Monroe and baseball star Joe DiMaggio . With Tony Curtis as McCarthy and Theresa Russell as Marilyn Monroe.

- McCarthy - Death of a Witch Hunter USA 1975, directed by Emile de Antonio

- Documentary about the McCarthy era.

- Tail Gunner Joe USA 1977, directed by Jud Taylor

- TV biopic about McCarthy.

- The Real American - Joseph McCarthy D 2011, book: Lutz Hachmeister, Simone Höller; Director: Lutz Hachmeister

- Docu-drama

Web links

- Literature by and about Joseph McCarthy in the catalog of the German National Library

- Joseph McCarthy in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk List of people and organizations observed or persecuted by McCarthy and his agency

- The Inexorable Descent of Senator McCarthy (Telepolis)

- Joseph McCarthy in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ William T. Walker: McCarthyism and the Red Scare. A Reference Guide. ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, London 2011, p. 8 .

- ↑ Also on the following Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 460 ff.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves: Tail Gunner Joe. Joseph R. McCarthy and the Marine Corps . In: Wisconsin Magazine Of History 62, No. 4 (1978/1979), pp. 300-315. ( online , accessed January 19, 2013 and July 11, 2013).

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 109-31, reference 114.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 109-59.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 123-9, reference p. 129.

- ↑ Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, p. 462.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 222-7, reference p. 224.

- ^ A b Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 205-33.

- ↑ Ronald Radosh and Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File . 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1984, pp. 5-19.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 222-33.

- ^ The President's News Conference, February 16, 1950, in: Public Papers of the Presidents: Harry S. Truman, 1945-1953 . [1]

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, p. 233.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 235-314, reference p. 304.

- ↑ Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, p. 462.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 349 and 197.

- ↑ “This must be the product of a great conspiracy on a scale so immense as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man. A conspiracy of infamy so black that, which it is finally exposed, its principals shall be forever deserving of the maledictions of all honest men. ... What can be made of this unbroken series of decisions and acts contributing to the strategy of defeat? They cannot be attributed to incompetence. ... The laws of probability would dictate that part of ... [the] decisions would serve the country's interest. "Richard Hofstadter: The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. London 1966, Chicago 1990 (reprint), p. 77 f. ( online at harpers.org); see. Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 371-2; Ellen Schrecker: Many are the crimes. McCarthyism in America Little, Brown & Co., Boston 1998, pp. 244-249.

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 456; see. McCarthy's address in Chicago, October 27, 1952, online at americanrhetoric.com, accessed January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Twenty years of treason". James Giblin: The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy . Clarion, New York 2009, p. 153.

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 456.

- ^ Richard M. Fried, Men Against McCarthy . Columbia University Press, New York 1976, pp. 219-53; Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 453-457.

- ^ "We've got McCarthy where he can't do any harm": Robert Griffith: The Politics of Fear. Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate . University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst 1987, pp. 207-211, reference p. 210; see. Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, pp. 456-60.

- ^ Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy. A biography . Stein & Day, New York 1982, p. 457; also Griffith, Politics of Fear , pp. 207-11.

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 457.

- ^ Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 459-67; Ellen Schrecker, Many are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America , Boston et al. a .: Little, Brown & Co., 1998, 255-60.

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 458.

- ↑ The minutes, which are printed in five volumes, have a total of 4,300 pages and can also be viewed on the Internet, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, 107th Congress, S. Prt. 107-84 - Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations (McCarthy Hearings 1953–1954) , Washington DC: GPO, 2003. Archive link ( Memento of July 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ McCarthy quotation "mismanagement, subversion, and kickbacks" in: Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 477.

- ^ Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 477-9; "Background Information Relating to the IIA Instruction of the Use of Materials by Controversial Persons", undated, in: Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954 , Vol.II, Washington DC: GOP, 1984, 1677–1681.

- ^ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954 , Vol. II, Washington DC: GOP, 1984, 1686-7.

- ^ Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 485.

- ^ Roy Cohn, McCarthy , New York: The New American Library, 1968, p. 81.

- ↑ McCARTHY: Hello, Franco! In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1953 ( online ).

- ↑ http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/welch-mccarthy.html - the famous exchange of words as an audio file

- ^ Diary entry of February 7, 1953, The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, The Presidency: The Middle Way , Vol. XIV, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins P, 1996, 27-9, here 29.

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/presidents/34_eisenhower/eisenhower_politics.html Presidential Politics

- ↑ US Senate Committee on Homel, Security, Governmental Affairs 340 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC, 20510224-4751 Get Directions Contact The Committee: History | Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee. Accessed August 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 669-672; Arthur Herman, Joseph McCarthy. Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator . Free Press, New York 2000, pp. 302-303; David M. Oshinsky, A Conspiracy So Immense. The World of Joe McCarthy . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, pp. 503-504.

- ^ Anne Stockwell: Clooney vs. the Far Right . In: The Advocate, December 6, 2005, p. 54.

- ↑ Arthur Herman: Joseph McCarthy. Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator . Free Press, New York 1999, p. 233; David M. Oshinsky: A Conspiracy So Immense. The World Of Joe McCarthy . Oxford University Press 2005, p. 451.

- ^ Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy , 669-72.

- ↑ Arthur Herman: Joseph McCarthy. Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator . Free Press, New York 1999, p. 283.

- ↑ http://seto.org/images/2005/mccarthy.jpg ( Memento of October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 458.

- ↑ Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 463 f .; see. Richard Hofstadter: The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. London 1966, Chicago 1990 (reprint), pp. 77-86, on McCarthy pp. 77, 82 and 85 ( online, accessed March 6, 2011 ( Memento of August 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Translated from: Ellen Schrecker, Many are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America , Boston a. a .: Little, Brown, 1998, p. 265.

- ↑ Translated from: http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cold.war/episodes/06/then.now/ ( Memento from March 1, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The Real American in: HMR Produktion GmbH

- ↑ CIA had McCarthy spied on by Communist hunters in: Spiegel Online of April 17, 2011.

- ^ Frank Noack: Review ( Rheinische Post January 13, 2012; p. C8).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | McCarthy, Joseph |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | McCarthy, Joe; McCarthy, Joseph Raymond; McCarthy, Joe R. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 14, 1908 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Grand Chute , Wisconsin |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 2, 1957 |

| Place of death | Bethesda , Maryland |