McCarthy era

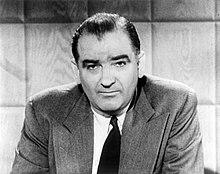

McCarthy Era (also: McCarthyism ) refers to a period in the recent history of the United States in the early stages of the Cold War . It was shaped by a loud anti-communism and conspiracy theories and is also known as Second Red Scare (German " Second Red Fear "). Although the eponymous Senator Joseph McCarthy only appeared in public from 1950 to 1955, the entire period of persecution of real or alleged communists and their sympathizers, the so-called fellow travelers , from 1947 to around 1956 is now referred to as the McCarthy era.

history

prehistory

During the Second World War , the USA and the Soviet Union were allied in the anti-Hitler coalition . Anti-communism declined. During this time, numerous immigrants from Germany and German-occupied Europe came to the country, many of whom, as determined anti-fascists , were leaning towards the political left . Many fertilized the intellectual climate of their host country, enjoyed the freedoms that the left-liberal climate of the New Deal era also offered for communists and socialists. They were involved in the American civil service, like the socialists of Jewish origin Herbert Marcuse and Franz Neumann , who worked for the OSS , the predecessor organization of the CIA .

After the end of the Second World War, relations between the two great powers cooled and the Cold War began. With the change of the external enemy image away from Nazis and fascists , to the Communists, especially the USSR and the People's Republic of China , also the domestic political climate changed: Roosevelt's New Deal was campaigning for the congressional elections in 1946 by the Republicans in the vicinity of communism moved and the Democratic party as " red fascists " (red fascists) insulted. In the elections, the Republicans won a majority in both houses of Congress.

The left was now perceived as a threat in American society. As early as 1939, the Hatch Act had required all applicants for federal employment to swear that they were not part of any organization advocating the violent overthrow of constitutional government. In 1940, President Roosevelt signed the Smith Act , which criminalized the call to overthrow the government. On March 22, 1947 Harry Truman ordered with Executive Order 9835 a review of the political loyalty of all employees of the federal authorities by a loyalty review board . Three million civil servants were screened, 1,210 dismissed, and a further 6,000 filed their resignation.

Executive bodies

The McCarthy era was characterized by summons and interrogations of political suspects before parliamentary committees of inquiry, e. As the House Un-American Activities Committee ( House Committee on Un-American Activities ; HCUA or HUAC) of the House of Representatives , in which particularly the Democrat Martin Dies Jr. (director from 1938 to 1944) and the Republican Richard Nixon excelled. The original task of this committee was to investigate people with communist or fascist connections. Another was founded in 1952 Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate (Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations), headed by Republican McCarthy. McCarthy had already been successful in 1950 with a conspiracy theory about alleged infiltration of government agencies by communists. He claimed he had a list of 205 names of current or former Communist Party members who , to the full knowledge of Secretary of State Dean Acheson , were employed in the State Department . This list did not exist.

Both committees worked closely with the FBI headed by J. Edgar Hoover . Civil servants were checked for their convictions as well as public figures and artists. These committees received support from anti-communist private organizations and interest groups such as American Business Consultants Inc. , AWARE Inc. or the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA), an association of filmmakers.

Investigations against the Communist Party

Although President Truman had dismissed the US Communist Party (CPUSA), which had 60,000 members in 1948, as "a contemptible minority in a land of freedom", the FBI and the Justice Department began collecting incriminating measures from 1946 onwards Material against the party. In 1949, eleven of its leading members were charged with violating the Smith Act and sentenced to fines and imprisonment in the so-called Foley Square Trial (named after the location of the trial, Foley Square, New York ). Judge Harold Medina then sentenced the defendants' lawyers to prison terms of up to six months.

In 1948, the Republican representatives in the HUAC, Karl Earl Mundt and Richard Nixon, introduced a bill, the so-called Mundt-Nixon-Bill, which was supposed to force all members of the Communist Party to register with the Attorney General by name . The motion passed the House of Representatives, but was not approved by the Senate, partly because Truman had announced that he would be vetoing it. A second motion, the Mundt- Ferguson Bill, also failed, but formed the basis for the so-called Internal Security Act or McCarran Internal Security Act (named after the applicant, Democratic Senator Pat McCarran), which came into effect in 1950. The law, which was specifically designed to combat communism on American soil, allowed, among other things, the arrest and detention of persons who "have reasonable grounds to believe that they are engaged in espionage or sabotage , either alone or as part of a conspiracy with others ". Truman vetoed in vain, which he justified, among other things, by stating that the law was a “danger to freedom of speech, press and assembly”. Congress approved the establishment of six detention camps , but they were not used.

Investigations against artists and the "black list"

In 1947, the actor Robert Montgomery and members of the Motion Picture Alliance such as Robert Taylor , Adolphe Menjou , Gary Cooper and Ginger Rogers declared before committees of the HUAC that Hollywood had been infiltrated by communists. Subsequently, filmmakers suspected of left sympathy were summoned to appear before the HUAC and given the choice of working with it or risking prison sentences. The first ten notable summonses and later convicts, including Dalton Trumbo and Edward Dmytryk , came to be known as the Hollywood Ten . At the same time, a group of representatives from Hollywood film studios, including Dore Schary , Samuel Goldwyn and Walter Wanger , decided to stop employing suspected film artists, which was tantamount to retiring from the film industry . This was the starting point for the so-called black list .

Walt Disney , MPA vice president, denounced three employees who had taken part in a strike at his company and who, in his opinion, posed a threat to his business, when he testified before the HUAC on October 24, 1947 . One of the three, the active trade unionist Herbert Sorrell, was in fact exposed as a contact for the Soviet secret service after the Russian archives were opened in 1991 , and according to other sources as a spy. Even Howard Hughes of RKO Pictures to the prevailing climate of fit, announced the "cleansing" of his production company of Communists and gave the production of the film I Married a Communist (later appeared as The Woman on Pier 13 ) in order. He had previously made one of his planes available so that members of the Committee for the First Amendment , an association of representatives of liberal Hollywood such as Humphrey Bogart , Danny Kaye and John Huston , could fly to Washington and protest the summons from the Hollywood Ten . In return, the Democratic HUAC member John E. Rankin sought to discredit critics such as Kaye, Edward G. Robinson and Melvyn Douglas by pointing to their Jewish origins.

A second wave of subpoenas before the HUAC began in 1951. Filmmakers were given the choice of either naming former or current communists and "comrades" or no longer finding employment in the film industry. As Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund point out in Inquisition in Hollywood , the names given to the committee during these interrogations were already known; The decisive factor was whether the summonses cooperated or refused, referring to the 5th Amendment to the United States Constitution , which put them on the blacklist themselves. The friendly witnesses who named names and were able to continue their careers included Elia Kazan , Budd Schulberg , Lee J. Cobb , Sterling Hayden , Lloyd Bridges and Edward Dmytryk, who was fighting for his rehabilitation. Uncooperative, unfriendly witnesses , like the directors Joseph Losey and Jules Dassin, emigrated to Europe or, like the actors Zero Mostel and Gale Sondergaard, found engagements exclusively in the theater from then on. Some uncooperative scriptwriters were still able to continue working because colleagues made their names available to them as straw men . One of the few left-wing authors who found employment in the early 1950s was Carl Foreman . He was sponsored by Gary Cooper , who has become a vocal critic of the HUAC despite his conservative convictions, but soon after he went to Europe too , when he was dropped by his business partner Stanley Kramer .

Although there was no “official” blacklist in the television industry , employees had to fear for their jobs if they were suspected. Director Martin Ritt was denounced and dismissed in a publication by AWARE Inc. for pro-Soviet donations from World War II . It was not until 1956 that he was given the opportunity to return to directing an independently produced film in New York City. Philip Loeb , popular speaker and performer on the radio and TV series The Goldbergs , lost his job because his name was mentioned in another privately published treatise called Red Channels . He fell into depression and took his own life.

The writer Thomas Mann emigrated to the USA during the Nazi regime . He publicly expressed his sympathy for the Hollywood Ten and his negative attitude towards the Mundt-Nixon-Bill . In June 1951, the Republican MP Donald L. Jackson read a newspaper article in the House of Representatives calling Mann “one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company” (“one of the world's most important apologists for Stalin and Co.”). The German emigrants Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht were invited to the HUAC. Eisler was expelled from the country for refusing to cooperate, and Brecht left on his own initiative. Who lives in the US, British citizen Charles Chaplin was because of his critical attitude towards the HUAC in 1952 after a promotion (for his film tour through Europe limelight denied) the re-entry.

Writer Arthur Miller and political folk singer Pete Seeger were both sentenced to prison terms for refusing to testify before the Un-American Activities Committee, citing their constitutional rights .

Investigations against civil servants

The conviction of former Roosevelt confidante Alger Hiss in 1950 attracted a lot of attention . Hiss had been publicly accused of pro-Soviet espionage by Whittaker Chambers , a former member of CPUSA and editor-in-chief of Time magazine. The subsequent media-effective process, massively promoted by Richard Nixon, only resulted in Hiss being convicted of perjury , but not only put Nixon in the wake but also Senator Joseph McCarthy in the spotlight. McCarthy claimed he had a list of 205 State Department employees who posed a security threat, including Roosevelt's China expert Owen Lattimore . The allegations were investigated by the specially established Tydings Committee (named after the Democratic Senator Millard Tydings from Maryland ), but not confirmed. McCarthy then supported Tyding's Republican opponent John Marshall Butler in the next Senatorial election in Maryland , who won thanks to a polemic media campaign.

Scientists' loyalty has also been called into question. One of them was Edward Condon , who among other things had been involved in the development of the radar and the Manhattan project to develop the first atomic bomb . Republican HUAC chairman J. Parnell Thomas called Condon “perhaps the weakest link in our nuclear security”. In return, President Truman attacked Thomas sharply at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science . According to Walter Goodman , author of The Committee , Thomas's allegations were based on the fact that Condon incurred the ire of the head of the Manhattan Project, General Leslie R. Groves , when he had successfully campaigned for the newly formed Atomic Energy Commission not to be placed under military, but civilian control. In 1951 Condon was finally able to rebut all allegations directed against him.

The nuclear scientist Robert Oppenheimer was also a victim of anti-communist investigations . In 1949, after he was ready to give the HUAC the names of left-wing students, to Condon's displeasure, his criticism of the incipient nuclear arms race and a denunciation by his colleagues Lewis Strauss and Edward Teller in 1954 led to a renewed summons and dismissal from the Atomic Energy Commission .

In 1952 the Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected the new President of the United States. In the same year the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and the Committee on Government Operations were created and McCarthy was appointed chairman in 1953. McCarthy immediately began checking the loyalty of employees on the state radio station Voice of America . He also ordered the removal of books from the State Department's libraries, such as the America Houses , whose authors were suspected of being Communists or their sympathizers, or, as the writers Howard Fast and Dashiell Hammett had refused to testify before his committee. Like the HUAC, McCarthy made use of the mass medium of television, on which the hearings of those summoned were broadcast. His advisers included lawyers Roy Cohn and Robert F. Kennedy . Cohn and G. David Schine personally went to the State Department libraries in Europe to make sure McCarthy's directives were being followed.

Social base

McCarthy's and HUAC's approach met with broad approval from a large part of the American population. In a study carried out in 1954, the sociologist Samuel A. Stouffer attested a widespread prevalence of conspiracy, uncritical anti-communism and intolerance towards divergent thinking and behavior, especially in rural and small-town layers of the Midwest . Since the interrogations were directed primarily against intellectuals , high-ranking government officials and other privileged persons, Jürgen Heideking and Christof Mauch believe that they “ manifested the urge of middle class society to make their own norms generally binding and political-cultural deviations from the accepted To keep the spectrum of opinions within the narrowest possible limits ”.

The end of the McCarthy era

McCarthy's power crumbled from 1954 when he began summoning high-ranking members of the United States Army and accusing them of communist sympathy. As a result, there were counter-charges by the army against his adviser Cohn. At the same time, Edward R. Murrow's television political magazine See It Now attacked McCarthy's methods, which resulted in his increasing loss of popularity. A motion introduced in the Senate by Republican Ralph Flanders led to a "reprimand" (censure) McCarthy and his disempowerment. In 1955 McCarthy had to give up his chairmanship of the Committee on Government Operations and disappeared into political insignificance. He died just two years later. The Committee on Government Operations was dissolved in 1977 and the Committee on Governmental Affairs took over its functions .

The HUAC remained active in the fight against political opponents, but increasingly lost its importance. The writer Arthur Miller , who in 1953 in his play The Crucible (Engl .: The Crucible ) the baiting of McCarthyism had criticized barely concealed, was summoned 1956th He appeared with his wife Marilyn Monroe and refused to give any names of companions. He was convicted and appealed, which was upheld in 1958 by the Washington Court of Appeals. In 1959, ex-President Truman described the HUAC as "the most un-American affair in this country today". In 1960, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was the first filmmaker who had been discredited by the HUAC and the blacklist to be named in two films, Exodus and Spartacus . The end of the McCarthy era was already apparent in television: in 1957, Alfred Hitchcock hired the unemployed actor Norman Lloyd as an associate producer for his series Alfred Hitchcock Presents .

Orson Welles and Lewis Milestone , who had not been summoned but preferred to work overseas in the heyday of the McCarthy era, returned to the United States in the mid-1950s; others, like Joseph Losey , stayed away from their former homeland permanently. While Gary Cooper and Sterling Hayden publicly regretted their cooperation with the HUAC, others like Elia Kazan or Budd Schulberg defended their cooperation to the very end. In 1969 the HUAC was renamed the Internal Security Committee and finally dissolved in 1975.

The McCarran Internal Security Act , which was never applied, has been repealed in parts over the years, for example in September 1971 under the Non-Detention Act .

The term "McCarthyism"

The term "McCarthyism" was coined by Herbert Block , a cartoonist for the Washington Post . On March 29, 1950, a few weeks after McCarthy's first announcement about alleged communists in the government apparatus , the Washington Post published a cartoon in which Robert A. Taft and other leading Republican politicians turned an elephant, the symbol of their party, into a rickety tower of tar buckets pilot, the top of which is labeled "McCarthyism". The elephant asks anxiously: "Do you really think I want up there are on it?" McCarthy grabbed the concept and turned it into something positive, "McCarthyism is Americanism with sleeves rolled up." In 1952 he was a collection of his anti-communist speeches under the title McCarthyism : The Fight for America out. Today, however, the term is mostly used with negative connotation for the demagogic communist hunt of the early 1950s, in which the hysterical fears of the population were exploited to persecute innocent or relatively harmless dissenters; it is associated with conspiracy theories and a “rule of terror ” in which no value was placed on conclusive evidence. Detached from the actual historical-political reference, the term is also used for the use of insinuations and unproven assertions, regardless of the purpose. Historically, McCarthyism did not prove to be a permanent corollary of the Cold War.

Artistic processing of the McCarthy era

Movies

- 1956: Storm Center - Director: Daniel Taradash

- 1957: A King in New York (A King in New York) - Director: Charles Chaplin

- 1962: Ambassador of Fear (The Manchurian Candidate) - Director: John Frankenheimer

- 1976: Der Strohmann (The Front) - Director: Martin Ritt

- 1976 Hollywood on Trial (Documentary) - Director: David Helpern

- 1991: Guilty by Suspicion (Guilty by Suspicion) - Director: Irwin Winkler

- 1995: Nixon - Director: Oliver Stone

- 2001: The Majestic - Director: Frank Darabont

- 2005: Good Night, and Good Luck - Directed by George Clooney

- 2011: The Real American - Joe McCarthy (documentary) - Director: Lutz Hachmeister

- 2015: Bridge of Spies - Director: Steven Spielberg

- 2015: Trumbo - Director: Jay Roach

theatre

- 1953: Witch Hunt (The Crucible) by Arthur Miller

- 1972: Are You Now or Have You Ever Been? The investigation against show business by the "Committee for the Investigation of Un-American Activities" 1947-1956 (Are You Now or Have You Ever Been. The Investigation of Show Business by the Un-American Activities Committee 1947-1956) by Eric Bentley

literature

- John E. Haynes: Red Scare or Red Menace? American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era. Chicago 1996, ISBN 1-56663-091-6 .

- Albert Fried: McCarthyism - The Great American Red Scare - A Documentary History. New York 1997, ISBN 0-19-509701-7 .

- Ellen Schrecker: Many Are The Crimes - McCarthyism in America. Princeton 1998, ISBN 0-691-04870-3 .

- Olaf Stieglitz: “What I'd done was correct, but was it right?” Public justifications for denunciations during the McCarthy era. In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History. 4 (2007), pp. 40-60.

Web links

- Hollywood 'Red' Probe Begins - excerpt from the newsreel from October 20, 1947 at archive.org (opening speech by the chairman of the first investigation tribunal and the chairman of the MPAA )

- Herb Block: Caricatures for the second Red Scare from the Washington Post

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Gid Powers: Not Without Honor. The History of American Anticommunism . Yale University Press 1995, pp. 257 f .; Michael Butter : Conspiratorial Thinking in the USA . In: Andreas Anton, Michael Schetsche and Michael Walter (eds.): Konspiration. Sociology of Conspiracy Thinking . Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014, p. 266 ff.

- ↑ Jürgen Heideking , Christof Mauch : History of the USA. 5th edition, A. Francke, Tübingen and Basel 2009, p. 272 f.

- ↑ Jürgen Heideking, Christof Mauch: History of the USA. 5th edition, A. Francke, Tübingen and Basel 2009, p. 303.

- ^ A b Gary A. Donaldson: The Making of Modern America: The Nation from 1945 to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Gary A. Donaldson: Truman Defeats Dewey. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Christof Mauch: Loyalty . In: Rüdiger B. Wersich (Ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 445.

- ↑ George McKenna: The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism. Yale University Press, 2007, p. 261.

- ↑ a b c History of the Committee on its official website, accessed December 28, 2012.

- ↑ Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO , Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2003, Vol. 2, p. 462.

- ↑ Arthur J. Sabin: In Calmer Times: The Supreme Court and Red Monday. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, p. 118.

- ↑ a b c Larry Ceplair, Steven Englund: Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community 1930–1960. University of California Press, 1983, pp. 193, 210, 378.

- ↑ Michal R. Belknap: American Political Trials: Revised, Expanded Edition. Praeger Publishers, Westpoint 1994, pp. 207 ff.

- ^ Francis H. Thompson: Frustration of Politics: Truman, Congress, and the Loyalty Issue, 1945-1953. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1979, pp. 79 ff.

- ↑ "[...] The detention of persons who there is reasonable ground to believe probably will commit or conspire with others to commit espionage or sabotage." - The McCarran Internal Security Act in full on Historycentral.com, accessed on June 11, 2012.

- ↑ Thesis paper The McCarran Internal Security Act, 1950–2005: Civil Liberties Versus National Security ( Memento of the original from February 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 312 kB), available on the Louisiana State University website, accessed June 11, 2012.

- ^ "[...] greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly [...]" - wording of the Veto of the Internal Security Bill on Trumanlibrary.org, accessed on June 11, 2012.

- ^ Wheeler Winston Dixon, Gwendolyn Audrey Foster: A Short History of Film. Rutgers University Press 2008, pp. 178-182.

- ^ A b c Brian Neve: Film and Politics in America. A social tradition. Routledge, Oxon, 1992, pp. 89-90, 171, 174.

- ↑ Steven Watts: The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. University of Missouri Press, 2001, p. 284.

- ↑ Carol Berkin et al. a. (Ed.): Making America: A History of the United States. Wadsworth, 2010, p. 624.

- ↑ Peter Schweizer: Reagan's War: The Epic Story of His Forty-Year Struggle and Final Triumph Over Communism. Doubleday, New York 2002, ISBN 0-385-50471-3 , p. 6.

- ↑ Donald L. Barlett, James B. Steele: Howard Hughes: His Life & Madness. WW Norton & Company, New York 1979, p. 180.

- ^ John Huston: An Open Book. Da Capo Press, Cambridge (MA) 1994, p. 132.

- ^ Brenda Murphy: Congressional Theater: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television. Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ James Naremore: More than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts. University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1998, ISBN 0-520-21294-0 , p. 123 ff.

- ↑ Review of the 1953 Berlin Film Festival at Berlinale.de, accessed on December 28, 2012.

- ^ Reynold Humphries: Hollywood's Blacklists: A Political and Cultural History. Edinburgh University Press, 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Victor S. Navasky: Naming Names. Hill and Wang / Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, New York 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Gabriel Miller (ed.): Martin Ritt: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2003, pp. 56-58.

- ↑ Actor Is Dropped from Video Cast; Philip Loeb Out of Goldbergs' After Name Appears in 'Red Channels' - He Will Appeal. In: New York Times . June 8, 1952, accessed December 29, 2012.

- ^ Walter Bernstein: Inside Out: A Memoir Of The Blacklist. Da Capo Press, 2000, p. 197.

- ↑ Otto Friedrich : City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940's. University of California Press, 1997, p. 412.

- ↑ Thomas Mann Called Apologist For Reds . In: Lodi News-Sentinel. June 19, 1951, p. 5, accessed December 29, 2012.

- ^ William T. Walker: McCarthyism and the Red Scare: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2011, pp. 44, p. 55.

- ^ Walter Goodman: The Committee: The Extraordinary Career of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York 1968, pp. 280-281.

- ^ Kai Bird, Martin J. Sherwin: American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Knopf, New York 2005, p. 398.

- ^ Alan L. Heil: Voice of America: A History. Columbia University Press, 2003, p. 51 ff.

- ^ Robert Griffith: The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press, 1970, ISBN 0-87023-555-9 , p. 214.

- ^ Christopher Finan: From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight for Free Speech in America. Beacon Press, 2008, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ James R. Arnold, Roberta Wiener (Ed.): Cold War: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2012, p. 124.

- ^ Louise Robbins: Censorship and the American Library: The American Library Association's Response to Threats to Intellectual Freedom, 1939-1969. Praeger, 1996, p. 76.

- ^ Samuel A. Stouffer: Communism, Conformity & Civil Liberties. A Cross Section of the Nation Speaks its Mind . Doubleday & Co., New York 1955.

- ↑ Jürgen Heideking, Christof Mauch: History of the USA. 5th edition, A. Francke, Tübingen and Basel 2009, p. 304.

- ↑ Michael Ratcliffe: Arthur Miller. One of the greatest playwrights of the 20th century, whose work explored the dilemmas of the American dream. In: Guardian . February 12, 2005 (obituary), accessed December 29, 2012.

- ↑ 1958: Arthur Miller cleared of contempt on BBC.co.uk, accessed December 29, 2012.

- ↑ Stephen J. Whitfield: The Culture of the Cold War. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, p. 124.

- ^ Victor Navasky, Ruth Schultz, Bud Schultz: It Did Happen Here: Recollections of Political Repression in America. University of California Press, 1990, p. 425.

- ^ Robert Sklar: On the Waterfront. In: Jay Carr: The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films. Da Capo Press, 2002, p. 207.

- ^ William G. Staples: Encyclopedia of Privacy, Volume 1 A – M. Greenwood, 2006, p. 284.

- ^ Statement by President Nixon on Signing the Non-Detention Act on The American Presidency Project, accessed June 17, 2012.

- ↑ "You mean, I'm supposed to stand on that?" In: Washington Post . March 29, 1950, accessed January 13, 2013.

- ↑ "McCarthyism is Americanism with its sleeves rolled." Quoted by Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 458.

- ^ Joseph McCarthy: McCarthyism: The Fight for America. Devin-Adair, New York 1952.

- ^ Rüdiger B. Wersich: McCarthyism . In: the same (ed.): USA Lexicon . Erich Schmidt, Berlin 1996, p. 456; Ellen Schrecker: The Age of McCarthyism. A Brief History With Documents . 2nd edition, Palgrave, New York 2002, pp. 120 f.

- ^ Jovan Byford: Conspiracy Theories. A Critical Introduction . Palgrave MacMillan, New York 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Mike O'Connor: McCarthy, Joseph . In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . Vol. 2. ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver and London 2003, p. 460.

- ^ McCarthyism. In: Collins English Dictionary, accessed December 29, 2012.

- ↑ Jürgen Heideking , Christof Mauch : History of the USA. A. Francke UTB. 6th edition, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8252-1938-3 , p. 304.