Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche District Hussars

The Mecklenburg-Strelitz District Hussars were soldiers in the state police service of the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz . The corps was established on September 1, 1798 as the Ducal Hussar Corps and was a militarily organized rural gendarmerie on horseback. The district hussars, initially stationed in Neustrelitz , were ready for action on October 1, 1798.

Prehistory and role models

prehistory

Police regulations were already issued in the Middle Ages, such as the Bützow Police Regulations of December 11, 1508, in which the rules for general coexistence were established. However, this had little in common with police regulations in the later sense.

By resolution of the Landtag in Sternberg in June 1610, six “Einspänniger” were accepted for payment. In the same year, the Einspänniger appeared for the first time. They are to be regarded as the first mounted Mecklenburg rural gendarme. Experienced mercenaries and servants , who were sworn in on November 27, 1610, served as country horses . Their duty was regulated by the Gendarmerie Instructions of December 3, 1610, the first such instruction for the Duchy of Mecklenburg. At that time six country horses were on duty. As a result of the division of the country in 1621, they were distributed to the different parts of the country, so that three single horses each served in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Güstrow . On March 3, 1627, single-horse soldiers were sworn in again, but their trace was lost in the turmoil and horrors of the Thirty Years' War . It was not until 1649 that the country horses reappeared. Duke Adolf Friedrich I set up a command of 20 country singles and a corporal , which were led by a lieutenant of Croatian origin. Due to disputes with the state estates, the command was dissolved again in December 1650, as the question of financial maintenance remained unresolved. The Duke now concentrated on the establishment of a standing army. Later, single horses mostly appeared in the dispatch service .

In the first half of the 18th century, soldiers of the standing army were called in for state police services. The so-called satellites and soldiers on foot occasionally performed such services in the Land of Stargard and Ratzeburg . The soldiers were also called in to support the regional riders. Their country visits were mainly at the inns and pitchers in the country, as these occasionally housed beggars and vagabonds . The existing Strelitz bodyguard on horseback was of low strength and corresponded more to a bourgeois guard . It was similar with the guard on foot , they too were completely unsuitable. So she was not able to prevent the breakout from the Altstrelitz penitentiary that took place in 1797 . The guard was then replaced by a separate night watch. The land riders appeared in the middle of the 18th century. They too were supposed to keep beggars, vagabonds and other "loose suspicious rabble" away. The last land riders were mentioned in 1798. Experience from this time would later flow into the formation of the Ducal Hussar Corps.

role models

In the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, some Land Dragons performed their patrol duty around 1750. These rider patrols were mostly used against stray people, and the clarification of tax matters was one of their tasks.

The Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin established a hussar corps in 1761, but it was severely decimated during the Seven Years' War . These hussars were led by Rittmeister Distler, who later appeared for embezzlement of funds from the hussar corps and desertion . In May 1764, the unmounted hussars abdicated. Then the hussars still in service were relocated to Ludwigslust on horseback. In the years that followed, the mounted hussars were mainly responsible for police and dispatch services. The appearance of the Schwerin hussars resembled the Zieten hussars that had served in Mecklenburg since 1780 in the 2nd Battalion of the Prussian Hussar Regiment No. 2 under Hans Joachim von Zieten .

As a rule, the state, mostly mounted police troops were referred to as dragoons , such as the police dragon corps of the Duchy of Oldenburg or the Jülich light dragoons corps , which were set up in 1781 with 60 men.

Foundation and organization

The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz District Hussars is one of a whole series of reforms that Duke Karl II , who has ruled in the Mecklenburg-Strelitz region since 1794, quickly tackled after his accession to the throne. Originally 12 district hunters were supposed to do their job in the respective districts , the duke gave his consent on August 16, 1797. Difficulties with the booths in the country led to a delay in the installation. From March 8 to 10, 1798, the class deputies in Neustrelitz negotiated with the government and the office of Kamptz. Here the difficulties in relation to the district hunters came up, followed by the proposal to employ district riders, as they could do their service on horseback just as well. The Duke wanted to give the corps the prestige of a sovereign military and pay for equipment, armament and horses. The stalls were supposed to pay for wages, food and meals. At the convention in Neubrandenburg on April 21, 1798 it was decided to accept some district riders based on the model of the Mecklenburg-Schwerin Hussars already used in the Stavenhagen office. The selected district riders should be obliged to serve for six years.

The district riders were now soldiers who carried out state police services.

Major Christian (Friedrich Ferdinand Anselm) von Bonin (born June 16, 1755 Magdeburg, † February 14, 1813 Neustrelitz), a former Prussian lieutenant in the Gendarme regiment of Berlin who had resigned in 1786, was tasked with setting up the corps In 1787 he was in the ducal service as chamberlain and director of the court theater and in 1798 he opened the first bookshop in Neustrelitz. The major estimated the expected costs of setting up the corps with 1900-2000 Reichsthalers , which were taken over by the duke. One consequence was that the horses of the guards on horseback were abolished to compensate for costs.

Major von Bonin recruited some of the staff from the Guard on Horseback . Of this guard, however, only three former members were available, one of whom had already been canceled in August due to illness and one was released in October because of drunkenness. Von Bonin recruited the rest of the hussars from various professions, including a few grooms and coachmen and a master baker. Two vice guardsmen also reported for duty. The age of the volunteers was between 20 and 40 years and the contractual employment was initially limited to six years. It was not until 1804 that they wanted to check whether the corps was performing well. On September 1, 1798, the installation was completed. On September 5th the Duke thanked Major Bonin in a personal letter. In the same letter, the naming of the corps was specified, which from now on was called the Ducal Hussar Corps .

The swearing-in of the hussars took place on September 26, 1798 in front of the ducal secret council and government college. When the hussars were sworn in, a special ducal decree was issued in which the behavioral guidelines were laid down. They were exhorted to "behave in an extremely orderly, moral and dutiful manner". Violation of these rules of conduct could result in Fuchtel (strict supervision) or dismissal.

The troop initially consisted of a sergeant and 12 district riders and was organized militarily, but intended exclusively for police purposes and not for national defense. Their employment should primarily apply to the "inhibition of any kind of begging and vagabonding".

On September 12, the Duke issued the “Beggars, Vagabonds and Poor Ordinance”, which also regulated the future activities of the hussars. Major von Bonin wrote the "Instructions for the Hussars" on September 25, using the ducal decree of September 12 as a template. The instructions stipulated that the hussar had to travel at least 2 miles within 24 hours. Within the district, the border towns should be patrolled twice a month, while the other towns should be patrolled once a month. These instructions were valid until 1855 and were subsequently replaced by new ones.

On October 1, 1798, the Ducal Hussar Corps finally began its operations. As a result, six hussars were sent to the newly created districts of the country. The sergeant and six other hussars remained in the royal seat . They served as a replacement or to patrol the residential district, whereby the orderly service was one of their tasks.

The remuneration was regulated separately. The sergeant got 8 Reichsthaler per month, the Hussars received 3 Reichsthaler and 24 schillings . The former guard riders continued to receive their 5 Reichsthaler. The former wood warden Kehtel also received his 50 Reichsthaler a year as usual. The district hussars were also granted concessions, such as tax exemption, a wood allowance and free medical care including the necessary medicine. The married hussars were also given gardens for self-sufficiency. Care for the service horses was also considered. During the service the hussar received a daily feed allowance of 20 shillings. The sergeant, however, received 32 schillings.

With the state ordinance of January 4, 1805, the Ducal Hussar Corps was finally established for an unlimited period. The six-year probationary period and its positive outcome had reinforced the Duke's decision.

In the state calendar of 1814, the name District and Ordonnanz-Hussars was mentioned for the first time . It can be assumed that this choice of name should serve to distinguish it from the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschem Hussar Regiment established in 1813 . However, the term district hussars had been present since the early years.

structure

Major von Bonin was initially entrusted with the management of the corps, but was not officially entrusted with the position of chief until July 4, 1800. For his services he received an annual salary of 200 Reichsthaler . Bonin had been in command of the Strelitz Life Guard on horseback since May 7, 1794 . On March 16, 1802, he was promoted to colonel. In 1808 he was also head of the Neustrelitzer troop contingent, taking 1812 as battalion commander of the Strelitz-Rhine Confederation quota on Russian campaign Napoleon Bonaparte's part. He returned to Neustrelitz seriously ill in January 1813, where he died shortly afterwards.

The first sergeant in the corps was the Prussian NCO Karl Ludwig Fallmer (born March 3, 1740 in Fürstenwalde, † August 29, 1807 in Neustrelitz), who was 57 years old in 1798 and had served with the Zietenhusars . Fallmer came to the Ducal Hussar Corps on the recommendation of the Rittmeister von Warburg. The non-commissioned officer was considered very reliable and well trained in dealing with subordinates.

Twelve hussars are known by name from the time the corps was established: Husar Peters, Mumm, Rinck, Wasmund, Fischer, Tolch, Lemke, Schulz, Kehtel, Ready, Bock and Borchert.

As a result of the war of liberation, some of the hussars were incorporated into the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Hussar Regiment as NCOs . In particular, Lieutenant Schuessler from the District Hussars participated intensively in training in the aforementioned regiment.

In 1849 the district and orderly hussars were led by a sergeant. Sergeant Wilhelm Roloff was supported by two NCOs.

In the 1850s, among other things, the Neustrelitz Premier Lieutenant Scheel commanded the Districhtshusaren.

In 1867, Captain Adolf Freiherr von Seckendorff (born March 9, 1829 in Trier , † June 18, 1878 in Neustrelitz) was in command of the district hussars. He was supported by Sergeant Seifert and Sergeant Renter, the latter being stationed in Schönberg. On the other hand, Medical Councilor Köppel took care of the physical well-being of the hussars .

The team stand was initially expanded continuously, while later it remained almost constant, as the following list illustrates.

| year | Team status 1798–1883 |

|---|---|

| 1798 | an officer, a sergeant, 12 hussars. |

| 1808 | one officer, one sergeant, one non-commissioned officer and 18 hussars |

| 1809 | Increase by one non-commissioned officer, four hussars for delivery and assignment to the Principality of Ratzeburg |

| 1809 | Increase by six hussars, deployed to guard duty at the Neustrelitz residential palace |

| 1813 | the corps grows to 33 hussars |

| 1816 | a sergeant, two NCOs, 24 hussars |

| 1824 | a sergeant, two NCOs, 22 hussars |

| 1849 | a sergeant, two NCOs, 22 hussars |

| 1855 | an officer, a sergeant, two NCOs, 22 hussars |

| 1859 | one officer, one vice sergeant, 1 sergeant, 22 hussars |

| 1867 | one officer, one sergeant, one sergeant, 24 hussars |

| 1883 | two constables, 14 hussars and 15 foot gendarmes |

Insinuation

The district hussars and foot gendarmes were subordinate to the State Police District Commissarius responsible in the station area. The commissarius was appointed by the state government, who was now entrusted with the supervision of the district hussars and foot gendarmes. The commander and the sergeant were designated as direct superiors of the gendarmes and district hussars, one sergeant for the Duchy of Strelitz and one for the Principality of Ratzeburg. The disciplinary criminal authority was incumbent on the superior officer, violations of discipline and official duties could be punished immediately. In contrast to the Schwerin gendarmes, who were completely subject to military jurisdiction, the Strelitz gendarmes were subject to the ordinary courts in all legal matters.

Operations and Chronicle

At first, Major von Bonin received detailed reports on the operations. This also included carefully examining the complaints from the hussars and about the hussars. The first reports of this kind reached von Bonin on October 27, 1798. The new passport controls led to all sorts of difficulties, as many traveled through the country without passports. The reports also showed that the use of the district hussars had already had a positive effect. Their appearance ensured that the rabble - as it was reported at the time - largely stayed away. However, the need of the people in Mecklenburg continued to increase around 1800, which provided the ideal breeding ground for crime. The Kruger in particular received the intensive attention of the District Hussars in the early years.

The Ducal Hussars Corps and the District and Ordonnance Hussars were entrusted with the following tasks:

- Prosecuting crimes .

- Capturing deserters .

- To keep away local and foreign beggars, as well as all other undesirable persons.

- The passport control.

- Deportation of the suspect across national borders.

- Have the jugs checked on suspicious people.

- Control of the annual markets in the district area.

- Monitoring and preventing trading in prohibited goods, if necessary to carry out the seizure .

- Monitoring the ban on smoking in public within the localities, in particular to prevent fires on thatched-roof houses. In the case of refusal, the pipe or the like was removed and handed over to the responsible office.

Clashes with the rural population did not fail to materialize. The district hussars were often forced to use physical violence, and the use of the saber was not uncommon. In 1801 one of the hussars was bitten in the arm by a farmhand in such a way that he was unable to work for a long time. There were also conflicts with the regional riders, who saw the district hussars as unwelcome competition.

Since 1805 it was possible to bring the vagabonds and beggars taken into custody by the district hussars to the Altstrelitz state labor, breeding and madhouse . A measure with a deterrent effect, because at the time the facilities were a place of horror. If a beggar was picked up for the first time, the hussar handed him over to the local authorities for an initial warning. If the same beggar was found again, he was sent to jail and subjected to corporal punishment. On the third encounter, a two-year sentence followed. The traveling people were treated in a similar way . They were threatened with deportation and the ban on entering the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The fourth violation of the entry ban was threatened with life sentence. Compared to the alleged offense, a draconian punishment .

From 1809 on, the state of Ratzeburg was mounted by the district hussars. The hussars were initially not permanently stationed in the Principality of Ratzeburg; permanent stationing followed years later.

On March 13, 1813, an agreement was signed between the duchies of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Mecklenburg-Schwerin. It made it possible for the inns in the border area to be checked and suspects to be arrested. From then on, the Strelitz district hussars were also authorized to act in the vicinity of the border in Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

In the years 1813-1815 the district hussars took part in the fight against the French occupation. Due to their qualifications, some of them were trained as NCOs who then fought in the ranks of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Hussar Regiment . The recruits were handed over to the sergeant or second lieutenant Schüßler to train them for combat. Second Lieutenant Schüßler later served in the 4th Squadron of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Hussar Regiment. Schüßler was seriously wounded in the battle near Möckern and died on October 16 on the battlefield.

After the wars of liberation, police force activities had priority again. The tasks of the hussars were adapted to the conditions found in the country in the following years. Which now also included the monitoring of the condition of the roads and compliance with state regulations.

The so-called forest crime was also a crime that the district hussars were entrusted with prosecuting. The forest protection was part of daily service and was regulated forestry outrage from 1 March 1842 concerning the Ducal regulation. From then on, the district hussars had to watch out for "suspicious traffic with wood". In addition, there was participation in house searches and searches, provided there were enough grounds for suspicion.

The district hussars received reinforcements in the spring of 1849 to support them in carrying out the police services in Strelitzer Land. On February 22nd, 1849 the "corps of foot gendarmes" was established. Initially with a team of ten foot gendarmes, who were former soldiers of the Strelitz Infantry Battalion.

Picked up beggars and tramps were handed over to the responsible authorities by the district hussars. The basis was the ordinance of 1798 and the amendment of 1805. This procedure led to increasing inconsistencies. The person in custody was either released immediately or deported as quickly as possible. Which, however, did not correspond to the ducal decrees. In the announcement of April 20, 1850, it was again determined that those apprehended: “not to be dismissed without further notice, resp. to have them transported across the border, but rather to drag them in accordance with the existing laws for examination and for punishment. " The order applied in particular to the Dominalamt and the landowners. The poor police administration played a decisive role during this time, because it also organized the deployment of the district hussars and the foot gendarmes.

In 1855 a new deployment instruction was issued. From now on, the corps had to act as the “State Police Institute for handling the police in the Grand Ducal Lands in accordance with the instructions” and “to perform ordinance services in accordance with its military organization”. The instruction from the founding time then lost its validity.

In the 1860s, the district hussars were also used to support the country's customs officials and were charged with supervising and controlling customs border traffic. Which, however, required the express consent of the stalls, as they issued the instructions.

On August 1, 1862, a new highway police order came into force. The previously valid arrangement of 1855 had proven to be inadequate and no longer up to date. The duties of the district hussars and gendarmes have also been reorganized in the new Chaussee Police Regulations. The district hussars therefore had to ensure compliance with the ordinance, in particular by monitoring and controlling the toll collection points, the inns on the highways and the tensioning there. In 1856 the training included the roads Dannenwalde - Neustrelitz, Neustrelitz - Neubrandenburg, Neubrandenburg - Friedland, Neubrandenburg - Woldek - Wolfshagen and the road Neubrandenburg - Treptow on the Tollense.

Vice-sergeant Collin died on January 16, 1867 in Schönberg. The sergeant was in charge of the district hussars in Schönberg for many years and was buried with military honors on January 22nd.

During the war 1870-71 Grand Duke was for the fighting troops in France Friedrich Franz I of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. A military police - detachment erected. Under the orders of the Schwerin Premier Lieutenant von Weltzien, three Strelitz district hussars were also deployed.

Caroline zu Mecklenburg died on June 1, 1876 . The district hussars provided a detachment for the funeral procession on June 7th . They accompanied the princely hearse from Neustrelitz to the Mirow Castle Church, with the hussars advancing and also forming the end of the funeral procession.

The powers of the district hussars have expanded considerably over the decades of their existence. In particular, the regulatory tasks in connection with dance events presented new challenges again and again. So they were entitled to intervene in fights, gross mischief and too loud dance music, which also included the immediate termination of such events. The trade in game was also subject to the supervision of the district hussars.

Not only the investigation of minor offenses was part of the daily work of the district hussars, as the successful investigation of a serious theft in July 1893 showed. On July 13, 1893, a serious burglary was committed in Selmsdorf, in which 40 marks , gold jewelry and clothing were stolen. The stolen landlord Lohse then reported the theft to the district hussar Kliege stationed in Selmsdorf. Soon afterwards the suspicion fell on a servant of Mr. Lohse. However, he had already gone in the direction of Lübeck and so District Husar Kliege and the injured party took up the pursuit. They had previously telegraphed to Lübeck and informed the authorities there. When he arrived in Lübeck, Kliege was finally able to arrest the perpetrator in the central hostel at Lederstrasse No. 3. Money and valuables were found and the perpetrator could be brought to Schönberg. Finally, Mr. Lohse expressed his gratitude in an advertisement in the weekly newspaper.

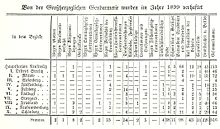

Statistics for the years 1899–1901 show to what extent the Strelitz district hussars and foot gendarmes were active:

| year | Arrests | Show |

|---|---|---|

| 1899 | 516 | 1062 |

| 1900 | 492 | 1091 |

| 1901 | 602 | 1230 |

Even at the beginning of the 20th century, the fight against vagabonding had hardly changed. The department of the interior of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Ministry points out - in contemporary vocabulary - on December 17, 1909: “That the gypsy mischief is again more noticeable in these years [...] so the local authorities are based on the announcement of January 3rd 1906 again pointed out […] to report the presence of gypsy hordes by telephone or telegraph to the Landespolizei-Districts-Commissarius. "

On June 23, 1910, a new ordinance came into force in the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, regulating the legal subordination to military jurisdiction. This ordinance states: “The members of the Grand Ducal Gendarmerie are soldiers. They are not only subject to the imperial and state criminal laws, but also to articles of war and the military penal code of the German Reich ... ”. As early as October 1900, an agreement was reached between the Royal Prussian War Ministry and the Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz Military Department that regulated submission to military jurisdiction. The agreement enabled the commander of the Strelitz gendarmerie to exercise lower jurisdiction. These ordinances had a direct impact on the operations of the district hussars and pedagogues. In 1908, the agreement of 1900 was amended again.

In addition to police duties, the hussars also often carried out messenger services for the ducal family and the state authorities. A task that so-called "Landreiter" and "Einspänniger" did before the establishment of the Ducal Hussar Corps, which appeared for the first time in the early 17th century.

In the last phase of its existence, the district hussars were often entrusted with representative tasks. As in the early days of the corps, the imposing appearance of a hussar on horseback played a decisive role.

With the incorporation into the Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Land-Gendarmerie , the more than 100-year history of the district and orderly hussars also ended. From then on, the district hussars served as mounted gendarmes and continued to do their duty in the districts.

The First World War then presented new challenges. Some of the mounted gendarmes were drafted into the war in August 1914. In the mobilization plan of 1914 two gendarmerie sergeants, two mounted gendarmes and two foot gendarmes were recorded. They were used in the formations of the field gendarmerie. This was followed by the deployment in the Mecklenburg regimental formations. The Strelitz gendarmes served there together with 20 mounted gendarmes from Schwerin.

In May 1917, the professional gendarmes were withdrawn from the Feldgendarmerie formations and replaced by NCOs from the regimental units. In the following years, the gendarmes were used to guard prisoners of war in the garrisons. In addition, there was the protection of traffic facilities and industrial facilities in the home area. A corresponding order from the General Command of IX. Army corps was sent to the Schwerin and Strelitz offices of the gendarmerie in mid-1917. This order was implemented accordingly until the end of the war.

Districts

The country was divided into six districts by 1808, which were expanded to eight districts in the same year. An appointed commissarius took over the supervision of the district hussars and foot gendarmes.

District hussars were sent to Schönberg and Ratzeburg on May 1st and November 1st. It was not until January 1875 that district hussars were permanently stationed in both cities. The district hussars Köster, Tabbert and Garz, who were on duty in the Principality of Ratzeburg at that time, said goodbye in the course of the changeover to permanent stationing, with a rather unusual message in the weekly newspaper: "When we are suddenly recalled from the Principality of Ratzeburg for the purpose of stationing, we say those Schulzen , Hauswirthen and Kruger , where we always found a friendly welcome , our best thanks and at the same time, as well as all friends and acquaintances, a warm farewell. " .

The number of districts was dependent on the political circumstances of the state and the needs of the state police. Therefore the classification changed several times.

Districts 1855

- I. Residence District

- II. Strelitzer District

- III. Mirower District

- IV. Fürstenberg District

- V. Feldberger District

- VI. Woldegker district

- VII. Friedländer District I.

- VIII. Friedländer District II.

- IX. Stargarder District

Districts 1869

- I. Strelitzer District, Commissarius Chamberlain of Fabrice

- II. Mirower District, Commissarius Drost Schröder

- III. Fürstenberg District, Commissarius Mayor Rath Bahr

- IV. Feldberger District, Commissarius Drost u. Chamberlain of Oertzen

- V. Friedländer District, Commissarius City Judge Plettner

- VI. Stargarder District, Drost, Commissarius Chamberlain of Fabrice

Districts 1881

- I. Strelitzer District

- II. Mirower District

- III. Wesenberger district

- IV. Fürstenberg District

- V. Feldberger District

- VI. Woldegker district

- VII. Friedländer District

- VIII. Stargard District

- IX. Neubrandenburg District

- X. Schönberger District (Schönberg station, Selmsdorf and Schlagsdorf secondary stations)

uniform

Duke Karl endeavored to give the corps the reputation of a "sovereign military", which should also be expressed in the uniform. The choice fell on the ornate hussar uniform, which was based on the tunic of the Prussian Zietenhusars stationed in Mecklenburg . The appearance of the Mecklenburg-Schwerin Hussars certainly had an influence on the decision. Their appearance was also based on the uniform of the Zietenhusars. This can be traced back to an equipment and clothing bill from 1787, because it shows a hussar in a typical Zieten uniform.

In addition, the hussars were considered a powerful force at the time. The resulting formidable appearance is likely to have had a positive effect on the rural police service.

Up to October 1905 the uniform consisted of a red dolman with 18 rows of cord, blue fur and blue trousers , with minor deviations . Dolman and fur had white lacing. The collar with silver braids and the lapels were blue in color. The hussars' white and blue sash was decorated with open tassels. The lapel on the fur was again made of black lambskin and initially lined with white lambskin, later with a red cloth. In the early days, the hussars had a light blue coat, which was later replaced by a black and gray mottled one. The fur was only worn in the winter period from October 1 to April 30 and with the parade uniform . The district hussar wore the fur to the parade over the dolman, on the left shoulder with hangings consisting of a white loop, toggle and tassels. In addition, a sash made of light blue cords with white tassels and knots was part of the parade equipment.

The trousers were made of blue cloth and trimmed with riding leather. At first, overbutton trousers were worn, along with high boots. Long breeches were introduced later, and from the 1870s on the breeches with high riding boots.

Of particular interest is the gala uniform and the equipment of the guard. The silver cord trim on the dolman and fur, the buttons silver-plated, as well as the crowned ducal monogram on the saber pocket and cartridge. In addition, the sergeant was equipped with a saber made entirely of silver. In the early days the sergeant wore a light blue Hungarian pekesche with silver-plated buttons, white cords and a blue velvet collar. With the end of the Wars of Liberation, however, this ceased to exist.

Until 1808 the hussars wore a black bearskin hat with a red Kolpak , which was then replaced by a black felt chako in the Russian form based on the Prussian model. The shako was provided with a round national and a brass clip that was gilded by the sergeant. Later, the blue-yellow-red provincial cockade and the brass star with the provincial coat of arms inserted were introduced.

Around 1870 the shako was temporarily replaced by the kepi based on the Austrian model. The cap was protected with a black oilcloth cover during use. At parades, the cap was provided with a black tail of hair that was attached behind the cockade. For the festivities of the ducal house, the hussars mostly wore their old headgear. So the bearskin hat and the old shako decorated with cordon, tassel and plume from the 1840s.

The shako, which the district hussars wore until they were dissolved, consisted of a string of cane sticks that were covered with red cloth and quilted between the sticks. The lid, along with the front and rear screens, was made of black leather, as was the narrow storm strap with a buckle. The white thread (cord) was found on the lid as an ornament of the coat of arms star made of brass or sheet metal with the state coat of arms inserted. The cockade and black tail of hair were worn as with the previous headgear. The shako was protected from the elements with a black oilcloth cover during use.

For work activities, the hussars had a separate headgear, the so-called forage hat. The red and blue headgear was worn during stable work and similar activities.

In 1870 the Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm II issued a "Circular to the Gendarmerie Corps". This stipulated that the district hussars would receive silver braids on the collar and lapels of the Dolmann and that the Dolmann would also have white buttons. The silver braid on the sergeant's shako fell away, instead the white braid was worn. The fur was only trimmed with silver braids on the collar and the sergeants continued to wear their insignia on their shoulder flaps.

The District Hussars appeared for the last time in their typical uniform at the funeral of Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm in 1904 and when Grand Duke Adolf Friedrich V visited Ratzeburg in 1906. From 1905 the hussar uniform (except for court service) was abolished and replaced by a blue tunic based on the Prussian pattern with green Swedish lapels, collars and armpit flaps. Yellow corporal stresses were worn on the collar. Dark gray mottled cloth trousers with red piping on the sides were worn with the uniform skirt. As head coverage were Shakos introduced in the form as it had the Mecklenburg hunters. The black leather gear and footwear formed the end. The appearance corresponded to that of the foot gendarmes who had been serving in the districts since 1849. By decree of June 19, 1906, it was now determined that the Strelitz gendarmes had to wear the name of Grand Duke Adolf Friedrich V on the armpits of their tunics and coats. The armpits of the Litevks also bore the new ducal monogram. The name was embroidered on the armpit flaps, while the armpit pieces were struck in metal.

Existing hussar uniforms were transferred to the State Theater after the November Revolution and used as props . They were later destroyed in a fire. Images of the hussar uniform can be found in the book Uniformkunde, Vol. XV by the author Richard Knötel . A pictorial representation of the parade uniform from 1905 with a red shako, black plume and slung fur can also be found on the uniform panels of the book “Vom Werden der Deutschen Polizei” from the time of National Socialism . Today preserved uniform parts of the district hussars are in the holdings of the Schöneberg Folklore Museum .

Equipment and armament

equipment

- Saddlecloth : The saddlecloth that was put on in parades over the saddlecloth was blue in color with red jagged trimmings, which in turn were trimmed with white braids. Around 1812 the sergeant was equipped with a saddlecloth made of white sheepskin.

- Saber pouch : Initially, the saber pouches were made of red-brown Russian leather, with a cover of red cloth, which was bordered by white braids. The applied ducal name "FW" was also made of white braids . It was later replaced by a brass fitting. The saber bags from 1810 were made of black leather.

- Cartouche : It was made of black leather with brass trimmings showing the ducal name "FW".

- Bandolier : The bandolier was made of red-brown Russian leather or black leather. The carabiner, however, included a white leather bandolier in Prussian design.

Armament

The armament consisted of a Prussian hussar saber , a carbine in various models and two flintlock pistols and then percussion pistols , which were replaced on April 18, 1876 by six-shot needle revolvers . Not only the 16 district hussars were equipped with these revolvers, but also the 9 land riders. The pistols were carried by the saddle, while the revolver was carried in a black leather revolver pouch on the right side of the body, which was held over the left shoulder by means of a strap.

From 1881 the district hussars wielded a dragoon saber , the thong of which was made of brown-red Russian leather and was also provided with a yellow tassel. The longer-serving hussars, on the other hand, wore the officer's portepee .

1913, 33 automatic pistols of the model Dreyse 07 cal. 7.65 mm acquired for the Strelitzer policeman. The gendarmes deployed to protect the residential palace were also equipped with the new pistols.

Whereabouts

The district hussars - also known as mounted gendarmes since 1905 - were incorporated into the Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Land-Gendarmerie in the course of the 1910s . Later, the foot gendarmes and mounted gendarmes of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Land-Gendarmerie saw themselves as successors to the district and orderly hussars in organizational history.

The effects of the November Revolution did not leave the police in Mecklenburg-Strelitz unscathed. As early as January 7, 1919, the new ministry - which now also had the supervision of the police - under the leadership of Johannes Richard Krüger began its business activities. In the period that followed, the organizational structure of the police also changed fundamentally. The Strelitz police system consisted - in 1920 - of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Gendarmerie , the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Land Gendarmerie and the local police . The Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Land-Gendarmerie was made up of eleven mounted gendarmes and 24 foot gendarmes as well as the seven gendarme candidates. As superiors, the commander Rittmeister Yrsch-Pienzau and the Oberwachtmeister Steinmann. The areas of responsibility were divided into the Beritt Neustrelitz , the Beritt Neubrandenburg and the Beritt Land Ratzeburg . In these areas the gendarmes were again spread over several stations.

When the National Socialists came to power, the structure and tasks of the Mecklenburg State Police also changed. As early as March 1933, there were purges within the Mecklenburg police. The Schwerin police chief, Hans Emil Lange, was taken into protective custody and later released from civil service. Officials of Jewish descent were particularly affected.

In May, Reich Governor Friedrich Hildebrandt ordered the commander of the Schwerin state police to unite the police forces of both Mecklenburg and Lübeck in a state police group. The police sovereignty of the federal states should not be influenced by this for the time being. The Strelitz police were then brought to a planned strength of 150 men.

From July 1, 1933, the Strelitz police recruits were trained in the training facilities of the Mecklenburg-Schwerin state police. The measure also announced the unification of the Mecklenburg parts of the state, which both state parliaments should approve on October 13, 1933. The abdicated Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV. And Duke Adolf Friedrich , who were invited as guests of honor of the NSDAP Reich Governor Friedrich Hildebrandt , also took part in the later ceremony in the Rostock Ständehaus . Subsequently, the state police administration was fundamentally restructured. In December 1933, the state police were divided into two departments, the 1st department Schwerin and the 2nd department Rostock.

Police sovereignty passed to the German Reich on January 30, 1934 with the law to rebuild the Reich. In May, the main teams of the districts in the larger cities were removed from the state police.

In 1936 the uniformed police of the Reich were united in the Ordnungspolizei . From then on, it was under the leadership of General der Polizei and SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer Kurt Daluege . In 1938 the Mecklenburg Police took part in the invasion of Austria and the occupation of the Sudeten German territories with delegations from the Schutzpolizei . After the war against the Soviet Union began , the Mecklenburg police officers were also deployed on the Eastern Front. There they were used, among other things, to guard and later evacuate the Riga ghetto .

Others

Misconduct

The hussars were not infallible either. Major von Bonin had to resort to disciplinary measures several times in the early days and released a hussar on October 24, 1798. The person had given the Stargarder caraway so much that he roamed through the town shouting and finally fell off his horse drunk. Another hussar forged a Schulzen's signature , resulting in a disciplinary punishment in the form of several weeks' suspension from duty. In 1801 and 1810 a hussar was released. Both were guilty of extorting traders. In a later fight against robbers and gangs, which was headed by the Kiel police master Caspar Diederich Christensen, cases of corruption were also found. Such incidents should remain the exception in the long history of the "Ducal Hussar Corps".

Mecklenburg-Schwerin District Hussars

On April 21, 1801, a District Hussar Corps was established in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, consisting of the sergeant, two NCOs and 32 hussars. The country was divided into 15 districts, each with two hussars serving. The Schwerin district hussars were organized like their model, with a commissarius and a knightly deputy in each district to whom the hussars were subordinate. Immediately after the establishment of the corps, Duke Friedrich Franz I issued a regulation for the: "Security institution against foreign beggars and vagabonds by a mounted military corps". However, the corps was disbanded in 1812 due to lack of effectiveness. Another reason was piercing, which Sergeant Trippenbach was guilty of, which led to his dismissal in 1811. After the corps was dissolved, the gendarmerie of the duchy was reorganized according to the French model.

Altstrelitz state workhouse

Altstrelitz had had a breeding and work house since the middle of the 18th century. With the increasing rush of people in need, this facility was hopelessly overwhelmed.

The state workhouse , based on the Prussian model, was created as a defense against begging and vagrancy . Picked up beggars were brought to these "institutions" to get them off the street. However, this did nothing to change the basic problem of the social hardship of those affected. The Altstrelitz state workhouse was built on the area known as the "Komödienberg", on an existing old foundation. Construction began in 1798. Construction work was completed in March 1801. The opening was delayed, however, only with the ducal decree of January 4, 1805, the institution was put into operation. The state workhouse was now part of the daily work of the district hussars, where they could spend apprehended beggars. From then on, the state workhouse was used as a workhouse, penitentiary and madhouse .

The organizational process in the state workhouse ensured:

- an inspector

- a foreman

- an overseer

- an overseer

- a doorman and turnkey

- a nurse

- a nurse

- a home cook

- a doctor

See also

Literature and Sources

literature

- Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginnings until today (= writings on the history of Mecklenburg. Volume 27). Schwerin 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035140-2 .

- Klaus-Ulrich Keubke, Ralf Mumm: Mecklenburg Military History 1701–1918 (= writings of the studio for history and portrait painting. Volume 5). Schwerin 2000, ISBN 3-00-005910-5 , p. 17.

- Paul Steinmann: The Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Landgendarmerie, its prehistory, its foundation in 1798 and its further development. A contribution to the Mecklenburg culture and class history. (Ed.) Heimatbund for the Principality of Ratzeburg, Schönberg i. M. 1924.

- Roland Schoenfelder, Karl Kasper, Erwin Bindewald: On becoming the German police. A folk book . Breitkopf & Härtel Verlag, Leipzig 1937, color plate no. 8, p. 213 f.

- Richard Knötel : Uniforms, on the history of the development of the military costume. Volume XV. (Ed.) Max Babenzien, Rathenow, plate no.6.

Unprinted sources

-

State Main Archive Schwerin

- Inventory: (3.1-1) Article XVII, Mecklenburg Land estates with the narrow committee of the knight and landscape of Rostock, occupation of the cities with billeting of the princely single horse, duration : 1670.

- Holdings: (2.21-1) 18931, Secret State Ministry and Government (1748 / 56–1849), agreement with Mecklenburg-Strelitz on the authorization for gendarmes and hussars to visit jugs and arrest suspects across borders, duration: 1812–1815.

- Inventory: (4.11-2) 516, (Acta Impressa) Mecklenburg-Strelitz (17th – 20th century), determination of the contributions to the salary of the land riders in the Principality of Ratzeburg, duration: May 31, 1774.

- Inventory: (5.12-9 / 7) 959, District Office Schönberg, personnel file for Gendarmerie-Wachtmeister / Landreiter / Amtsreiter / Amtshauptwachtmeister Georg Woisin, duration: 1908–1936.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Paul Steinmann: The foundation of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). In: Carolinum. Historical-literary magazine. Volume 42, Göttingen 1978, No. 79, p. 10.

- ↑ a b c d e The Mecklenburg-Strelitz Gensdarmen or District Hussars. In: CCF Lisch : Mecklenburg in Pictures. Volume 4. Hof-Steindruckerei JG Tiedemann, Rostock 1845, p. 8 f.

- ↑ The name refers to the one horse or steed with which they provided their service. They served against pay for a limited period, pay and length of service were previously recorded in a service contract.

- ^ A b c Paul Steinmann: The Mecklenburg-Strelitzsche Landgendarmerie, its prehistory, its foundation in 1798 and its further development. In: Carolinum. Historical-literary magazine. Volume 42, Göttingen 1978, No. 78, pp. 11-15.

- ↑ LHAS 2.21-1 Secret State Ministry and Government (1748 / 56–1849), No. 1426: Use of cavalry patrols to chase away the rabble and prevent tax fraud, circular ordinance of December 8, 1745 on the use of land dragons to help raise taxes, duration: 1745-1760.

- ^ Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginning until today. Fonts for Atelier u. History painting, Schwerin 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ LHAS 2.21-1 Secret State Ministry and Government (1748 / 56–1849), No. 5216: Restriction of the military budget and reduction of some Mecklenburg troops, hussars, body regiment, von Glüersches Regiment, Major von Zülowsches Regiment, von Bothsches Regiment, artillery regiment, duration : 1763-1764.

- ^ Representation of officers of the "Jülich Dragoon Corps", 1st officer from 1785, 2nd officer from 1788

- ↑ Barbara Hahn: The importance of political and economic reforms for development in the duchy. In: Altschülerschaft des Carolinum Neustrelitz (Hrsg.): Carolinum historical literary magazine. No. 125. Göttingen 2000, pp. 20–29 ( digitized version ( memento of the original dated December 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. [PDF; accessed on December 29, 2016]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805) . CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, pp. 7-20.

- ↑ Barbara Hahn: The emergence of a bourgeois institution of literature in Mecklenburg-Strelitz around 1800. A study on the basis of the regional intelligence paper "New Strelitz Ads" and "Useful Contributions to the New Strelitz Ads". Diss. Phil., University of Greifswald 1993.

- ↑ a b Klaus-Ulrich Keubke, Ralf Mumm: Mecklenburgische Militärgeschichte 1701–1918 (= series of publications by the studio for history and portrait painting. Volume 5). Schwerin 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). In: Carolinum: Historical-literary magazine. Volume 42, Göttingen 1978, No. 79, p. 20.

- ^ Werner Behm: The Mecklenburg 1812 in the Russian campaign . (Ed.) R. Hermes, Hamburg 1912, p. 28 ff.

- ↑ a b c Memorabilia of the Mecklenburg-Strelitz Hussar Regiment in the years of the War of Liberation 1813–1815 . Published by G. Brünslow, Neubrandenburg 1854, p. 20 f.

- ^ Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Calendar 1849. Print and copy. Verlag GF Spalding & Sohn, Neutrelitz 1849, p. 93.

- ^ Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Calendar 1859 . Pressure and Verlag GF Spalding & Sohn, Neutrelitz 1859, p. 100.

- ^ A b Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginnings until today (= writings on the history of Mecklenburg. Volume 27). Schwerin 2011, p. 39.

- ^ A b c Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 18 ff.

- ^ A b Paul Steinmann: The foundation of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 17.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration. No. 9 (1842). P. 44 f.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration. No. 7 (1850). P. 25 f.

- ↑ Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Calendar 1856. Printing and publishing house GF Spalding & Sohn, Neutrelitz 1856, p. 111 f.

- ^ Moritz Karl, Georg Wiggers: The Mecklenburg tax reform, Prussia and the customs union. Julius Springer Publishing House, Berlin 1862, p. 28.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration. No. 13/14 (1862). P. 76 f.

- ↑ Weekly advertisements for the Principality of Ratzeburg. No. 7, January 22, 1867. p. 1.

- ^ Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginnings until today (= writings on the history of Mecklenburg. Volume 27). Schwerin 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ Weekly advertisements for the Principality of Ratzeburg. No. 45, June 9, 1876. p. 2.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburgische Landvogtei Ratzeburg, announcement of March 21, 1885. In: Weekly advertisements for the Principality of Ratzeburg . No. 27, April 3, 1885.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburgische Landvogtei Ratzeburg, announcement of November 26, 1856. In: Weekly advertisements for the Principality of Ratzeburg . No. 50, December 12, 1856.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration . 1900-1902.

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration. No. 1 (1910). P. 3 ff.

- ^ Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginnings until today (= writings on the history of Mecklenburg. Volume 27). Schwerin 2011, p. 52.

- ↑ a b LHAS inventory: 5.12-8 / 1, no. 731, use of NCOs instead of professional gendarmes in the field gendarmerie formations, prevention of any damage to objects that may be used in warfare or the war economy .

- ↑ Großherzoglich Mecklenburg-Strelitzischer official gazette for legislation and state administration , 1869, p. 201.

- ↑ Weekly advertisements for the Principality of Ratzeburg, No. 2, January 5, 1875, p. 1.

- ↑ 2nd Battalion of the Prussian Hussar Regiment No. 2 .

- ↑ Erna Keubke: tunic and shako for the gendarmerie. In: Mecklenburg-Magazin. No. 14 (1994). Landesverlags- und Druckgesellschaft Schwerin, p. 4.

- ↑ The color nuances of the red color change over the years, initially brown-red, later from scarlet-red color.

- ↑ The fur is initially light blue, later dark blue.

- ^ A b c Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805) . CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 10 ff.

- ↑ LHAS inventory: 4.11-1 / 3, No. 838, Circular to the Gendarmerie Corps.

- ↑ a b c Erna Keubke: The splendor of the Strelitzer (district) hussars. In: Mecklenburg-Magazin. No. 2 (1997). Landesverlags- und Druckgesellschaft, Schwerin, p. 4.

- ^ Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginnings until today (= writings on the history of Mecklenburg. Volume 27). Schwerin 2011, p. 48.

- ↑ Roland Schoenfelder, Karl Kasper, Erwin Bindewald: From becoming the German police. A folk book. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1937.

- ^ A b Paul Steinmann: The foundation of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805) . CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 13.

- ↑ The carbine or long guns were not used in everyday service.

- ↑ LHAS inventory: 4.12-1 / 3, no. 867, decree / approval of the Grand Duke Friedrich Wilhelm II., Purchase of new revolvers and to distribute them against the demand of the old firearms .

- ^ Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). Instructions for the Hussars of September 25, 1798 , CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 17.

- ^ Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Hans Emil Lange

- ↑ a b Beate Behrends: With Hitler to Power, Rise of National Socialism in Mecklenburg and Lübeck 1922–1933 , Neuer Hochschulschriftenverlag Dr. Ingo Koch & Co KG, Rostock 1998, p. 161 ff.

- ^ Klaus-Ulrich Keubke: The Mecklenburg Police. A chronicle from the beginning until today . Fonts for Atelier u. History painting, Schwerin 2011, pp. 127–161.

- ^ Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805). CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 20.

- ^ Archives for regional studies in the Grossherzogthümen Mecklenburg and revue of agriculture. Volume 5. Verlag der Hofbuchdruckerei von AW Sandmeyer, Schwerin 1855, p. 437 f.

- ^ Paul Steinmann: The establishment of the Mecklenburg-Strelitzschen (district) hussar corps in 1798 and the first years of its existence (until 1805) . CLN Jhrg. 42, No. 79, Göttingen 1978, p. 20.

- ^ Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Calendar 1824 . Pressure and Verlag GF Spalding & Sohn, Neustrelitz 1824, p. 94.

- ↑ a b Grand Ducal Mecklenburg-Strelitz State Calendar 1856 . Pressure and Verlag GF Spalding & Sohn, Neustrelitz 1856, p. 112.