Nefertiti

| Nefertiti (with addition) in hieroglyphics | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Nefer neferu Aton Neferet iti) Nfr nfrw Jtn Nfr.t jy.tj The beauties of Aton are beautiful, the beautiful has come |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

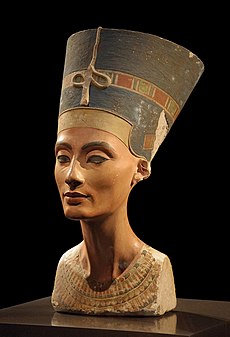

Bust of Nefertiti , Egyptian Department ( Egyptian Museum Berlin ) in the Neues Museum Berlin |

|||||||||||||||||||

Nefertiti (pronunciation: [ nɔfʁəˈteːtə ]) (in other languages mostly "Nefertiti", Egyptian Nfr.t-jy.tj , original pronunciation about Nafteta ) was the main wife ( great royal wife ) of the king ( Pharaoh ) Akhenaten (Amenophis IV.) and lived in the 14th century BC The queen became known for the bust of Nefertiti made of limestone and plaster , which is exhibited in the Egyptian Museum in the north dome of the Neues Museum ( Museum Island ) in Berlin .

Name and title

Her name Neferet-iti means “The beautiful has come” and is written in a cartouche from the 5th year of Akhenaten's reign with the nickname Nefer-neferu-Aton (“The beauties of Aton are beautiful ”) . Nefertiti bears the title “Great Royal Wife” and “Lady of the Two Lands”, which is attested on some Talatat blocks from Karnak . In the tomb of Akhenaten she appears as the "ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt". In some texts she is also titled as " Great in favor " and on a ushabti as "princess and great in the palace".

origin

No reliable statements can be made about Nefertiti's childhood or her ancestry. According to earlier assumptions, her name “The beautiful has come” was interpreted to mean that she was of foreign origin. This has not yet been proven archaeologically. Attempts to equate her with the Hurrian Taduhepa , the daughter of King Tušratta , were unsuccessful. Experts are now of the opinion that Nefertiti belonged to the Egyptian upper class and did not only come to Egypt when he was marriageable. The royal grave of her husband in Achet-Aton gives evidence of this , in which Tij , the wife of the later King Eje , is referred to as the "great nurse" of Nefertiti. Accordingly, it would be possible that Nefertiti was Eje's daughter from a previous marriage and Tij was her stepmother, who she raised as a half- orphan. According to a less popular theory, she could also be a daughter of Amenhotep III. be from a branch line. It is also controversial whether Nefertiti was the sister of Mutnedjmet , Haremhab's second wife . In the records she appears as the “sister of the queen”, but her name could also be read as Mutbeneret .

Life

Marriage with Amenhotep IV.

Whether the marriage with Amenhotep IV took place before or after the accession to the throne cannot be clearly established. Nefertiti had a total of six daughters. During the first years of the reign, the two eldest daughters, Meritaton and Maketaton, are born. The third daughter Ankhesenpaaton , who later became the wife of Tutankhamun , followed around the year 7 and is the last princess who is still represented in Thebes . Up to the twelfth year of reign, Nefertiti gave birth to three more daughters, Neferneferuaton , Neferneferure and Setepenre , of which only Neferneferuaton probably survived their parents. Nothing is known about the two sons. Nefertiti and Akhenaten were the first royal couple to have their private life depicted in public, as evidenced by numerous intimate family scenes with their daughters. The entire royal family is always protected in these representations by the rays of the solar disk of Aten .

In the extensive building program that Amenhotep IV started in Karnak, Nefertiti is already shown in almost all of the reliefs together with the king. In one of the four new Aton sanctuaries, the "House of Benben ", she appears without a husband and performs the same ritual acts as the king, alone or with her daughters, ranging from offering the mate to knocking down the enemy .

After the fourth year of reign there was a break with the old Amun religion. Amenhotep IV adopted his new proper name Akhenaten . Nefertiti got her name affix “The most perfect is Aton” and put her personality behind the new Aton cult. At the same time, the move to the new government city of Achet-Aton was completed.

Nefertiti as co-regent

In the Amarna epoch , which was now beginning , it played an important role in both religious and political life. The generally strong position of women in ancient Egypt was particularly enhanced under Akhenaten for Nefertiti. She was made into a kind of co-regent and at least symbolically endowed with pharaonic power. The famous blue crown on the bust is the high crown specially developed for Nefertiti and represents a counterpart to Chepresch , a war helmet. Symbolic or ritual acts normally performed by the king alone were now also performed by the queen. She was depicted several times in pharaotypical scenes such as warfare or the knocking down of the enemy. It is also shown on the chariot or included in the awarding of the honor gold , which is otherwise only carried out by the king alone.

The family scene , a kind of altarpiece of the royal family, which is in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin , perhaps even suggests that government was in the hands of Nefertiti, while Akhenaten, on the other hand, took care of religious and cultic matters. In the depiction, the queen sits on a chair with the symbol of the union of the two countries ( sema-taui ). Normally this place was reserved for the king, who embodied the role of the “King of the Two Countries” and thus succeeded the first unifier, Menes . Another indication of their special political position can be found in the tomb of Panehsi in Amarna. Here she can be seen with the royal Atef crown , which until then was only the only woman to be worn by Hatshepsut .

Her position as equal to the king is supported by many other representations. Her name is used in double cartridges, as is otherwise only the case with kings. Like Akhenaten and Aten, she wears the Uraeus , which is a symbol of rule, and there are groups of statues that show her stepping, like only male kings otherwise. In Akhenaten built at Karnak avenue of sphinxes facial features correspond sphinxes also one half those of the king and the other half those of the queen.

In the rock tombs of Amarna she was depicted several times together with Akhenaten in a way that today researchers even assume a dominant co- reign of Nefertiti, as Semenchkare , in the late years of Akhenaten's reign. On the reconstructed corners of her husband's stone sarcophagus, she was depicted as his patron goddess.

Nefertiti as successor to Akhenaten

One theory is that, contrary to all previous assumptions, she survived Akhenaten and took the throne after him. The portrayals of Nefertiti in pharaonic contexts ( see above ) and the portrayal as the patron goddess of her deceased husband at the corners of the reconstructed stone sarcophagus of Akhenaten, which has been preserved in fragments, are interpreted by more and more researchers to mean that she even ruled Egypt for a short time after Akhenaten's death . There are further indications: According to one thesis, it is identical to semenchkare. The Egyptologist Cyril Aldred demonstrated that the Amarna art style shows distinctions between men and women, depending on whether the neck is concave or convex. Semenchkare and Nefertiti both have a female neck and Semenchkare's name bears the epithets "Beloved by Wa-en-Re", which were also part of Akhenaten's throne name . At the enthronement a new name was adopted. This is a strong indication that Nefertiti might have ascended the throne under the name Semenchkare. It is unclear, however, whether Nefertiti was the king's widow who wrote to the Hittite court to offer a Hittite king's son the marriage (the Dahamunzu affair ).

death

Both the reason for Nefertiti's death and the place and time are unknown. Previous assumptions have dated the year of death to 1338 BC. BC, the 14th year of Akhenaten's reign. Other sources suspect her death in the 12th year of reign. Marc Gabolde assumed that Nefertiti had lived at least until shortly before Akhenaten's death. There was also speculation as to whether she might have been murdered or cast out. Death from sudden illness was also considered. If she had acceded to the throne as King Semenchkare , she disappeared after a few years, together with her daughter and co-regent Meritaton .

In December 2012, scientists from the Flemish Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium announced the opening of the exhibition In the light of Amarna. 100 years ago Nefertiti discovered that at the beginning of the year they had discovered an inscription in a quarry near Akhet-Aton , which names both Nefertiti and Akhenaten in his 16th year of reign ("year 16, 3rd month, day 15"). During Akhenaten's reign, the Deir Abu Hinnis quarry served as the main source of material for his new capital, Akhet-Aton. The five lines in hieratic script name Akhenaten's name and designate Nefertiti in the third line: "Great royal consort, lover, mistress of the two countries, Neferneferuaton Nefertiti." This discovery removes the basis of all previous hypotheses and speculations about the queen's whereabouts after Akhenaten's 12th or 14th year of reign.

Mummy and grave

The inscriptions on the older border steles in Achet-Aton envisage the mountain of Achet-Aton as the burial place of the king, his great royal wife, his daughters and the Mnevis bull. It says about Nefertiti: “(Even) if the great royal wife (Nefertiti), she will live in millions of years, dies somewhere, be it north, be it south, be it west or where the sun rises, then should they can be fetched so that their burial can be made in Achet-Aton . "

Rock tomb No. 26 is Akhenaten's royal tomb , which was intended for himself and members of the royal family. There is evidence that the burials of Akhenaten and Maketaton took place here, as evidenced by the remains of the sarcophagi and numerous shabti and fragments of the king's canopic box .

The first traces of the whereabouts of Nefertiti's mummy and her burial can be found in the royal necropolis in Amarna (the former Achet-Aton), where two fragments of a shabti figure were found, which is why it can be assumed that Nefertiti was also buried here. The fragments have the following inscription:

"Princess, grandeur of the palace, blessed of King Akhenaten, great royal wife"

If the ushabti was not made long before Nefertiti's death, it indicates a continued reign of Akhenaten at the time of her death, which would speak against Nefertiti's sole rule or equation with Semenchkare.

When the Amarna cemetery was closed, all the mummies in Thebes were placed in the Valley of the Kings , and Akhenaten's body in particular seems to have been reburied in grave KV55 . Teje ended up in the mummy depot in KV35 , where the Younger Lady (KV35YL) is also located. The mummy was originally believed to be that of Nefertiti, but DNA analyzes from 2010 could rule out this identity. Although the Younger Lady was clearly the mother of Tutankhamun, a direct relationship with Amenhotep III could also be found. and Teje, which does not seem to be present in Nefertiti. A possible alternative for the whereabouts of Nefertiti's mummy is the Deir el-Bahari cachette . This theory was at times preferred by Nicholas Reeves , who repeatedly theories about the burial place of Nefertiti. In 2000, for example, he said he had found a new grave in the Valley of the Kings (15 meters north of KV63 ) with the help of ground penetrating radar data . He referred to it as KV64 and linked this grave of the 2006 radar anomaly to Nefertiti. Excavations under Zahi Hawass revealed no trace of a grave at this point.

In 2015, Reeves published an essay in which Nefertiti's final resting place is believed to be in Tutankhamun's tomb KV62 . In high-resolution photos from the grave, Reeves wants to see walled up doors to other rooms. The grave was originally laid out for Nefertiti and she was buried in it. According to this theory, Tutankhamun was buried in an antechamber. This explained the unusual arrangement of the plant.

Nefertiti in art

portrait

Early stage

In the portraits , a distinction is made between two development phases, which are clearly demarcated from one another. In the older phase, which extends from the 2nd to the 5th year of reign, the extreme style prevailed , in which the depictions of Nefertiti were partly based on the royal portrait. It is characterized by extreme, unnatural highlights of individual body parts such as the pelvis, buttocks, hips, stomach and thighs. Not only the shape of the body, but also the shape of the face and head were very similar to Akhenaten's. Nefertiti was given a long, angular face, almond-shaped eyes, full lips, a protruding chin, a wrinkled, long, thin neck and a receding forehead.

Due to the mutual alignment of the royal couple in the representations, it is difficult to draw any conclusions about the real figure of Nefertiti. Rather, it is a religious style. Akhenaten tried to take on the form of the creator god by adopting female forms, whereas Nefertiti adopted male royal features. Such portrait resemblances are not unusual. You can already find them in Amenhotep III. and Teje and go back to the Old Kingdom , as the triad and dyad representations of Mykerinos show.

At the same time, however, Nefertiti continued to build on the tradition of great royal wives . She kept traditional queen attributes and even developed them further. In some of the images she continues to wear the three-part woman's wig, the Hathor crown with a sun disk and cow horns, the Nubian wig or the double oreus typical of queens . A new feature is the specially developed High Crown , which can be seen as a counterpart to the King's Blue Crown .

Later style

The younger style began with the move to Achet-Aton and was characterized on the one hand by a return to the conventional Egyptian representation of women and on the other by new, characteristic, individual facial features. It was characterized by a rectangular face type, with a straight chin and strongly pronounced, masculine lower jaw angles , but also narrow shoulders, an upwardly shifted waist and an elongated, two-part hip area . Overall, a softening or harmonization of the “extreme style” can be observed, in which gender-specific features are more strongly emphasized, but male royal symbols are retained.

Several portraits come from Thutmose's workshop , in which the famous bust of Nefertiti was found, each of which characterizes the queen differently and which may have been created by several sculptors. Dorothea Arnold derived five different display types from this:

- The Definite Image ( Das Idealbildnis), (Nefertiti bust Berlin 21300)

- The Ruler ( The Ruler ), Nefertiti as "Mistress of the Two Countries" (head from Memphis JE 45547 )

- The Beauty ( The Beauty ), Nefertiti as a gentle, beautiful queen (yellow quartzite head Berlin 21220)

- Nefertiti in Advanced Age ( The Elder ), the Queen as an experienced, wise woman ( standing figure Berlin 21263)

- The Monument ( Monument ), monumental portrait of the ruler for posterity (Granodioritkopf Berlin 21358)

the ideal

portrait (Berlin, No. 21352, limestone , height 29.8 cm)the beauty

(Berlin, No. 21220, quartzite , height 30 cm)the monument

(Berlin, No. 21358, granite , height 23 cm)

Nefertiti thus stands firmly in the tradition of Egyptian kings, who at the beginning of their reign were often based on their predecessors and only developed their own, individual portraits during their reign.

Exhibits from various museums

Nefertiti bust in the new exhibition room ( north dome hall of the Neues Museum, Berlin )

Relief ( Egyptian Museum Cairo )

Akhenaten and Nefertiti ( Louvre )

Nefertiti slaying the enemy ( Museum of Fine Arts in Boston )

Nefertiti making an offering ( Brooklyn Museum )

Nefertiti on postage stamps, in a review and on television

The German Post AG brought by 1988/1989 with the initial issue date January 2, 2013 again a stamp out with the bust of Nefertiti. The design of this special postage stamp with a value of € 0.58 comes from Stefan Klein and Olaf Neumann from Iserlohn .

The Friedrichstadt-Palast Berlin used Nefertiti as a peg for their revue The Wyld , which was performed from 2014 to 2016.

Crime scene in Egypt: the Nefertiti case . Documentation, 45 min., Production: ZDF -Expedition, first broadcast: June 3, 2007.

The Odyssey of Nefertiti. German treasure hunter finds “colorful” bust of Nefertiti . Documentation, 45 min., Production: ZDF-Expedition, first broadcast: July 29, 2007, summary of July 16, 2007 ( memento of July 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), summary of September 21 , 2007 ( memento of September 2, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

literature

(sorted chronologically)

- Cyril Aldred : Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Egypt. A New Study. Thames & Hudson, London 1968; German title: Akhenaten. God and Pharaoh of Egypt. Translated from the English by Joachim Rehork, Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1968.

- Philipp Vandenberg : Nefertiti - An archaeological biography. 1975, ISBN 3-7042-4024-9 .

- Christian E. Loeben : A burial of the great royal wife Nefertiti in Amarna? The dead figure of Nefertiti. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute , Cairo Department. (MDIAK) No. 42, von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 99-107.

- Peter France: The robbery of Nefertiti. The sack of Egypt by Europe. Diederichs, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-424-01231-9 .

- Christine El-Mahdy : Tutenchamun. Life and death of the young pharaoh. Blessing, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-89667-072-7 .

- Gabriele Höber-Kamel: Under the rays of the Aton. In: Kemet issue 1, 2002, ISSN 0943-5972 .

- Joann Fletcher : The Search For Nefertiti. The True Story Of An Amazing Discovery. William Morrow, Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, New York 2004. ISBN 0-06-058556-0 .

- Carola Wedel : Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3544-X , ( Antike Welt , special issue; Zabern's illustrated books on archeology ) ISBN 978-3-8053-3544-7 .

- Gabriele Höber-Kamel: Nefertiti. In: Kemet issue 3, 2010, ISSN 0943-5972 .

- Michael E. Habicht : Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2011. ISBN 978-3-7338-0381-0 .

- Bénédicte Savoy (Ed.): Nefertiti. A Franco-German affair 1912–1931. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20811-0 .

- Katja Lembke (editor and author): Hannovers Nefertiti. The portraits of Sent M'Ahesa by Bernhard Hoetger (= NahSichten. No. 2, Landesmuseum Hannover). Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7954-2627-9 .

- Franz Maciejewski : Nefertiti. The historical figure behind the bust. Osburg, Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-940731-80-7 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Nefertiti. The truth about the beautiful queen. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63725-4 .

- Dietrich Wildung : The many faces of Nefertiti. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2012; German / Arabic: ISBN 978-3-7757-3484-4 ; English / Arabic: ISBN 978-3-7757-3485-1 ; French / Arabic: ISBN 978-3-7757-3551-3 .

- Nicholas Reeves : The burial of Nefertiti? ( Amarna Royal Tombs Project. Valley of the Kings Occasional Paper No. 1 ). Tucson 2015 ( online at Academia.edu ).

- Michael E. Habicht, Francesco M. Galassi , Wolfgang Wettengel , Frank J. Rühli : Who else might be in Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb (KV 62, c. 1325 BC)? Working paper at the University of Zurich (CH) from October 15, 2015, doi: 10.13140 / RG.2.1.4408.1361 ( full text as PDF file ; online at Academia.edu ).

- Martina Dlugaiczyk: Series star Nefertiti. New sources on the 3D reception of the bust before the Amarna exhibition of 1924 . In: Christina Haak , Miguel Helfrich (Ed.): Casting. An analog route into the age of digitization? A symposium on plaster molding by the Berlin State Museums. arthistoricum.net, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-946653-19-6 , pp. 162-173 , doi : 10.11588 / arthistoricum.95.114 .

- Joyce Tyldesley , translator Ingrid Rein: Myth Nefertiti. The story of an icon. Reclam, Stuttgart 2019

Web links

- Information on Nefertiti in the online database of the National Museums in Berlin

- Audience with Nefertiti, Neues Museum, State Museums in Berlin. Retrieved March 23, 2020 .

- Literature by and about Nefertiti in the catalog of the German National Library

- Exhibition: In the light of Amarna. 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti . (December 7, 2012 to April 13, 2013)

- ZDF, Terra X (archive): The crime scene in Egypt - The Nefertiti case , July 3, 2007

- Rolf Krauss: Nefertiti. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on September 3, 2008.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard Fecht: Amarna problems. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 85, 1960, pp. 83–118.

- ↑ a b Isa Böhme: Nefertiti - attempt at a biography. In: Kemet issue 3/2010 , p. 11.

- ↑ Höber-Kamel: The divine queen - Nefertiti, wonderful in charm. In: Kemet issue 1/2002 , pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Marc Gabolde : The end of the Amarna period . In: Alfred Grimm , Silvia Schoske , The Secret of the Golden Coffin. Akhenaten and the end of the Amarna period . Munich 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ a b Isa Böhme: Nefertiti - attempt at a biography. In: Kemet issue 3/2010 , p. 12.

- ↑ Erik Hornung : Akhenaten. The religion of light. Artemis, Zurich 1995, ISBN 978-3-7608-1111-6 , p. 46.

- ↑ a b Höber-Kamel: The divine queen - Nefertiti, wonderful in charm. In: Kemet issue 1/2002 , p. 20.

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley : The Queens of Ancient Egypt. From the early dynasties to the death of Cleopatra. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-7338-0358-2 , p. 133.

- ↑ Sabine Neureiter: Nefertiti and the Amarna religion. In: Kemet issue 3/2010 , pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Nefertiti: The beautiful Egyptian king consort was an ice-cold power politician. In: Wissenschaft.de. April 24, 2009, accessed September 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Athena Van der Perre: Nefertiti (for the time being) last documented mention. In: In the light of Amarna - 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti . Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection State Museums in Berlin. Imhof, Petersberg 2012. ISBN 978-3-86568-842-2 , pp. 195-197.

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten - Tutankhamun. Harrassowitz Collection, 1993, ISBN 3-447-03359-2 , p. 106.

- ^ Royal Tomb - Amarna Project .

- ↑ a b Orell Witthuhn: The body of a woman. In: Kemet issue 3/2010 , p. 20.

- ↑ Zahi Hawass, YZ Gad, S. Ismail u. a. Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family . In: Journal of the American Medical Association. (JAMA) February 17, 2010, Volume 303, No. 7, pp. 638-47, doi: 10.1001 / jama.2010.121 .

- ^ Another New Tomb in the Valley of the Kings? Interview from August 3, 2006. On: archeology.org ; last accessed on January 31, 2016.

- ↑ a b 'Very little evidence' that Nefertiti is buried near Tutankhamun ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . On. theartnewspaper.com on August 21, 2015; last accessed on January 31, 2016.

- ↑ Is Nefertiti in Tut's Tomb? On: newyorker.com (The New Yorker.) August 16, 2015; last accessed on January 31, 2016.

- ↑ a b c Jennifer Peppler: The role of Nefertiti in the Amarna reliefs . In: Kemet issue 3/2010 , p. 30.

- ↑ Maya Müller: The Art of Amenophis III. and Akhenaten. Verlag für Ägyptologie, Basel 1988, ISBN 978-3-909083-01-5 , p. 87.

- ↑ Wafaa el-Saddik : The royal family in the art of the Amarna period. In: Christian Tietze: Amarna. Living spaces - life images - world views. Arcus-Verlag, Potsdam 2008, ISBN 978-3-940793-27-0 , p. 245.

- ↑ Maya Müller: The Art of Amenophis III. and Akhenaten. Basel 1988, p. 109f.

- ↑ Julia Budka: The Art of the Amarna Period . In: Kemet issue 1/2002 , pp. 41–42 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Dorothea Arnold : The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York NY 1996, ISBN 978-0-8109-6504-1 , pp. 65-83.

- ↑ Julia Budka : The Art of the Amarna Period . In: Kemet issue 1/2002 , p. 42.

- ↑ German Post Philately: mint - The Philatelic Journal. January / February 2013.

- ↑ The Egyptologist sums up the current knowledge, e.g. B. the role played by the mother of at least six children in political and religious matters. The author also tells the story of the bust, from its creation by Thutmosis to its rediscovery and theft from Egypt, and about the current restitution dispute between Egypt and Germany.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Nefertiti |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nafteta; Nefertiti |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient egyptian queen |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 14th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 14th century BC Chr. |