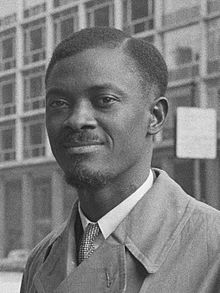

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (born July 2, 1925 in Onalua near Katako-Kombé ; † January 17, 1961 near Élisabethville in Katanga ) was a Congolese politician and from June to September 1960 the first Prime Minister of the independent Congo (previously Belgian Congo , 1971 to 1997 renamed Zaïre , now the Democratic Republic of the Congo ).

Life

Career and political beginnings

Lumumba's birth name was Tasumbu Tawosa . It was only later that he was called Lumumba, which means "rebellious masses". On the other hand, Klüver comments on the interpretation of the name: "Because he has the qualities of a spokesman: Lumumba means something like" team "in the language of the Batetela." Because of his behavior, he had to leave school (Protestant mission school "Fathers Passionists"); he was able to begin training as a postal worker in Stanleyville . He was serving a prison term for embezzlement. He later acquired legal and literary knowledge through correspondence courses. In 1946 Lumumba became a clerk at the Yangambi Post Office and a little later a clerk at the Stanleyville Post Check Office. He was active in the club of the "évolués" (educated Africans), organized cultural events, took part in scientific research and from 1952 wrote articles for periodicals such as "La Croix du Congo" or "La voix du Congolais". At first he belonged to liberal circles, later he was involved in the civil servants' union "l'Apic", which was organized purely in the Congo.

In 1958 he was one of the founders of the Mouvement National Congolais Lumumba (MNC-L) advocating for the independence of the Congo , which was the only party in the Congo that was able to anchor itself in all parts of the country. Soon after, he took a leading position there. As the spokesman for the independence movement, he was arrested in October 1959, tortured and released on January 25, 1960 in order to still be able to attend the round table conference in Brussels. At the invitation of Elsie Kühn-Leitz , he and two management cadres of the MNC-L then traveled to Wetzlar , where they were brought into contact with representatives of West German business and the West German state. In return for any help in the upcoming elections to the national and regional parliaments, Lumumba gave a written promise to politically bind the MNC-L to the West. He worked closely with the freedom fighter Andrée Blouin .

Time as prime minister

From the first parliamentary elections on May 25, 1960, Lumumba's party, the Mouvement National Congolais , emerged as the strongest political force. When the Congo gained its independence from Belgium on June 30, 1960 , Lumumba became the first prime minister of the liberated young republic - despite great opposition from the white settlers and the leading upper class of the country . The office of president went to Joseph Kasavubu (1910-1969; in office from 1960 to 1965).

Lumumba emerged as a staunch advocate of freedom and dignity during the independence ceremony. In a speech he contradicted the Belgian King Baudouin (1930-1993), who praised the "achievements" and the "civilizing merits" of colonial rule . In the presence of the king and the gathered dignitaries from home and abroad, he contradicted this view of history and, addressing King Baudouin, denounced the oppression, disregard and exploitation by the Belgian colonial administration.

“[...] degrading slavery that was imposed on us by force. […] We got to know grueling work and had to do it for a wage that did not allow us to drive away hunger, to dress or to live in decent circumstances or to raise our children as loved ones. […] We know ridicule, insults, and beatings that were incessantly distributed in the morning, at noon and at night because we were negroes . [...] We have seen our country being divided up in the name of supposedly legitimate laws that in fact only say that the law is with the stronger. [...] We will not forget the massacres in which so many perished, nor the cells into which those were thrown who did not want to submit to a regime of oppression and exploitation. "

After this speech, King Baudouin wanted to leave the Congo immediately, but his ministers advised him to stay for the final dinner out of courtesy. At this dinner, Lumumba tried to reconcile King Baudouin with an eulogy about achievements in Belgium outside of colonial rule.

The Belgians released the Congo into independence completely unprepared due to the long colonial rule. During the colonial period, the “mother country” hardly cared about fair conditions, social welfare, medical care or the education system. There were no Congolese officers. Only three Congolese held senior positions in the entire civil service, and there were only 30 Congolese educated nationwide. On the other hand, the Belgian and Western interests in the strategically important mineral resources of the Congo ( uranium , copper , gold , tin , cobalt , diamonds , manganese , zinc ) were all the greater. In addition, there were agricultural resources such as cotton , precious wood , rubber and palm oil . The immense investments associated with the exploitation on the economic level on the one hand and the deliberate neglect of human resources, the educational system and social institutions on the other hand gave the colonial rulers the opportunity to keep the country de facto under control even after independence.

The Belgian government saw Lumumba as a danger because, as a socialist, he wanted to nationalize the rich mining and plantation companies. The Belgian state put pressure on the media to ruin Lumumba's image. The Belgian press described him as a communist and anti-whites, which he always rejected. A West German newspaper caricature even described Lumumba as a negro premiere . After his death, the title of a Belgian newspaper was "The Death of Satan" (la mort de Satan).

Lumumba tried to unite the heterogeneous forces, to preserve the unity of the country and to build his party into a unified national movement based on the model of Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah . This was opposed by the whites who remained in the Congo - settlers, business people and the army, which was still under the command of Belgian officers - but especially the great power of the USA.

Earlier, Lumumba had not received the support it wanted during a visit to US President Dwight D. Eisenhower , and it became clear to the US side that Lumumba’s policies would jeopardize the interests of American companies involved in the Belgian monopoly of mineral exploitation in Katanga province were. A few weeks later, members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff proposed the assassination of Lumumba at an informal conference with representatives from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), State Department, and Department of Defense . When Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for military support against the Belgian troops, his telegram intercepted by the CIA reached Washington faster than Moscow . The Cold War was at its height, and resistance to Lumumba could be justified on the claim that Lumumba intended to bring the country under the influence of the Soviet Union.

On July 12, 1960, Lumumba went to the breakaway province of Katanga. Belgian troops stationed there refused his plane permission to land. Lumumba and Head of State Kasavubu then asked the United Nations (UN) and its Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld for help and declared war on Belgium. Belgium then increased its troop presence in Katanga, and the UN sent the first units to Léopoldville .

Putsch and planned assassination attempt against Lumumba

The following events became known as the " Congo Troubles ". President Joseph Kasavubu , with the support of the United States, joined forces with Colonel Joseph Mobutu (who later called himself Mobutu Sese Seko), a former companion of Lumumba, against the latter. Lumumba was dismissed from his post as Prime Minister on September 5, 1960 at the urging of the USA. Lumumba then declared Kasavubu deposed. A day later, the Congolese parliament reversed Lumumba's dismissal. On September 12, 1960, Kasavubu initiated the renewed release and instructed the new commander-in-chief of the army, Mobutu, with the arrest of Lumumba. However, he was able to evade it.

On September 14, 1960, the army under Mobutu took power in a coup agreed with the United States . Kasavubu remained the official head of state. Lumumba was placed under house arrest but remained under the protection of UN forces. Thereupon the head of the Central Intelligence Agency in the Congo, Lawrence R. Devlin, received the order to kill Lumumba, apparently on orders of US President Dwight D. Eisenhower personally.

Escape and murder

On November 27, 1960, Lumumba managed to escape from Léopoldville; shortly afterwards he was arrested by Colonel Mobutu's troops at Mweka ( Kasaï ) and taken to Thysville on December 1, 1960 to be available for a trial. After a military mutiny in Thysville on January 13, 1961, Lumumba was able to flee to Élisabethville ( Katanga ) on January 17 with two of his followers . There he was attacked on his arrival and went into hiding again. On February 10, rumors spread that he had escaped. Moïse Tschombé's government announced on February 13th that Lumumba had been killed by residents who were hostile to him. Because the Red Cross's request to see him in Katanga while he was being held was consistently denied, it is widely believed that the regime murdered him before his death was announced. Protests were held in many parts of the world in the face of these events. Other sources assume January 17, 1961 to be the date of his death and differ in the presentation of the circumstances of death.

Coming to terms with the murder

The exact circumstances of Lumumba's death were long unknown to the general public. According to some sources, he was so badly mistreated on the flight to Elisabethville that he died shortly afterwards. His son François Lumumba then brought charges in Belgium to investigate the circumstances surrounding his father's death. An investigative commission set up by the Belgian parliament on March 23, 2000 reconstructed the events surrounding Lumumba's death and presented its final report on November 16, 2001 - forty years after the crime. The report in Dutch and French is 988 pages.

Accordingly, Lumumba and his companions were captured by Mobutu's men, dragged by plane to Moïse Tschombé in Katanga and brought there to a forest hut. Lumumba and his followers Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo were tortured. Afterwards, his political opponents Tschombé, Kimba and Belgian politicians appeared, insulted the prisoners and spat at them. On January 17, 1961, Patrice Lumumba and his two followers were shot by Katang soldiers under Belgian command and initially buried on the spot. To cover up the fact that corpses were a few days later exhumed . Lumumba's body was cut up, disintegrated with battery acid provided by a Belgian mining company, and his last remains were finally cremated. The killing was attributed to the villagers (Lumumba assassiné par des villageois). Most of the media saw the culprit in Chombé.

In its final report, the commission came to the conclusion that the Belgian King Baudouin knew of the plans to kill Lumumba and did not pass this knowledge on to the government. What is certain is that the Belgian government supported Lumumba's opponents in the Congo logistically, financially and militarily. King Baudouin is blamed for having pursued his own post-colonial policy by bypassing political authorities.

Previous investigations had come to the conclusion that the killing of Lumumba was ordered directly by the governments of Belgium and the USA and carried out by the American secret service CIA and local aides financed by Brussels . The American Church Committee published documents in 1975 and 1976 suggesting that as early as August 1960, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave the CIA the order to liquidate Lumumba using poison. On September 26, for example, a CIA scientist named "Joseph Schneider", who was actually the head of MKULTRA , Sidney Gottlieb , arrived in the Congolese capital Léopoldville to collect deadly biological materials (e.g. Anthrax , tuberculosis , tularemia ). Leads Tim Weiner in his 2007 published work CIA: The whole history of more documents.

On June 22, 2010, Lumumba's son Guy-Patrice Lumumba announced in Brussels a lawsuit against twelve Belgians allegedly involved in the 1961 murder of his father. The lawsuit was due to be filed in a Brussels criminal court in October 2010. In December 2012, an appeals court in Brussels ruled that the Belgian public prosecutor's office could start an investigation into Lumumba’s murder. [obsolete] As a result of this decision, then Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt officially apologized to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In early 2013, Calder Walton wrote in his book Empire of Secrets: British intelligence, the Cold War and the Twilight of Empire about the history of the British secret service MI6 that it was unclear who organized the Lumumba assassination and what role Britain played in it. After a criticism of Calder's work appeared in the London Review of Books , the politician David Lea wrote to the magazine that this was no longer unclear. Daphne Park reported to him a few months before her death that MI6 had had something to do with Lumumba's execution, as it was organized by her. Park de facto directed MI6 operations in Léopoldville from 1959 to 1961.

See also subsection Documentaries .

family

About a year after his arrival in Stanleyville, Lumumba married Henriette Maletaua. The marriage lasted until 1947. In June 1947 he married Hortense Sombosia, from whom he was divorced in February 1951. Neither marriage resulted in children.

In 1947 Lumumba met his future lover Pauline Klie for the first time in Leopoldville, who at that time already had a daughter. She had moved to Leopoldville with her mother and father, who worked for the Office des Transports congolais (OTRACO) . The relationship ended when their family moved away before they met again in Stanleyville in 1948. On September 20, 1951, Pauline Klie Lumumba's first child gave birth to François. She moved back to Leopoldville when Lumumba married that same year. However, the two should keep in touch: Lumumba financially cared for his son, and Pauline Klie visited Lumumba during his house arrest in 1960.

Lumumba's third marriage to Pauline Opago (* approx. 1937) was the result of an arranged wedding in 1951. His brother Emile had promoted Lumumba to the Opago family in Wembo-Nyama. From this marriage there were four children:

- Patrice (born September 18, 1952)

- Juliana (born August 23, 1955)

- Roland-Gilbert (* 1958)

- Marie Christine (1960–1960)

In 1960 Lumumba met his secretary and later lover Alphonsine Masuba, who gave birth to their son Guy after his death.

reception

Lumumba as a symbolic figure

Patrice Lumumba became a political myth and a pioneer of the African independence movement. As a charismatic leader and victim in the struggle for the freedom of the Congo from colonial rule , he became a symbol of the anti-imperialist struggle in Africa.

"Mort, Lumumba cesse d'être une personne pour devenir l'Afrique toute entière [...]"

“Since Lumumba died, he ceased to be a person. It becomes all of Africa. "

Honors

From 1961 to 1992 the Moscow University of Friendship of Peoples was named after Patrice Lumumba. In 1961, a memorial for him was inaugurated in front of a university building in Leipzig . This was desecrated in 1997 and renewed and unveiled in 2011 on a private initiative and financed by donations. Another monument can be found in Bamako , the capital of Mali . In 1961, the Soviet Post issued a commemorative stamp for Lumumba. The Escola Preparatória Patrice Lumumba in São Tomé and Príncipe is dedicated to him.

In October 2013 a bronze cast of the sculpture "Lumumba (transfer to Thysville)" by the sculptor Jenny Mucchi-Wiegmann was set up on Garrisonkirchplatz, Berlin-Mitte and presented to the public by Lothar C. Poll and the Congolese ambassador Clémentine Shakembo Kamanga . The original from 1961 is in the art collection of the Akademie der Künste Berlin-Brandenburg . Lumumba’s eldest son, François Emery Tolenga Lumumba, and Senator Leonard She Okitundu also attended the ceremony.

Music, poetry and theater

Paul Dessau composed the Requiem for Lumumba in 1963 based on a text by Karl Mickel , actually a passion music in the aftermath of Bach's passions. It premiered in Leipzig in 1964. Peter Hacks dedicated a poem to the circumstances of Lumumba's death.

Irish politician and journalist Conor Cruise O'Brien published the play Murderous Angels in 1968 . Its German version by Dagobert Lindlau was published in 1971 under the title Murderous Angels . O'Brien had worked for UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld from May 1961 , who died in September 1961 on a Congo peace mission and whose death was also linked to King Baudouin. O'Brien accuses Hammarskjöld and the western world of being to blame for the "fall and death" of Lumumba.

The German premiere of the play Im Kongo by Aimé Césaire at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg on February 24, 1968 became an event that went down in German theater history. SDS members distributed leaflets even before the performance, slogans directed against US imperialism and the Springer press were chanted during the performance, and after the performance 400 to 500 spectators stayed in the theater and discussed with the director until well after midnight of the theater, the director, the Lumumba actor and the Césaire publisher, Klaus Wagenbach, on the political intention of the play and its theatrical implementation.

In the following year, 1969, Césaire's Lumumba play was also staged in the GDR, namely at the Deutsches Theater in East Berlin in a version that Heiner Müller gave a new, more theatrical end and completely re-translated. However, after the state had appointed a new, “loyal” director, he simply removed the practically finished production from the program without any explanation.

Documentaries

Raoul Peck , a Haitian by birth who spent part of his childhood in Léopoldville, released the documentary Lumumba - Death of the Prophet in 1990 . His feature film Lumumba followed in 2000 (French with German subtitles). The co-production by France, Belgium, Haiti and Germany shows the rise and assassination of Lumumba. The title role is played by the French actor Eriq Ebouaney .

The TV documentary Mord im Kolonialstil by Thomas Giefer from the year 2000 (for which he received the Adolf Grimme Prize with Gold) summarizes the events of that time based on interviews with several former employees and officers of the CIA and the Belgian secret service. They admitted for the first time in front of the camera that they were personally involved in the killing of Lumumba and his companions, as well as the removal of the remains. The former Belgian police commissioner Gérard Soete still had Patrice Lumumba’s incisors, which he also showed.

Further documentaries / TV reports were made in 2006 on the occasion of Lumumba's 45th anniversary of Jihan El Tahri and Birgit Morgenrath's death.

Trivia

The mixed drink Lumumba was named after him.

See also

literature

- Julien Bobineau: Colonial Discourses in Comparison. The representation of Patrice Lumumba in Congolese poetry and in Belgian drama. LIT Verlag, Berlin 2019. ISBN 978-3-643-13801-9 .

- Andrea Böhm : God and the crocodiles - A journey through the Congo. Pantheon Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-570-55125-7 .

- Mathieu Kirongozi Bometa: Patrice-Émery Lumumba. You nationalisme virtuel à l'humanisme patriotique. Harmattan, Paris 2020, ISBN 978-2-343-19121-8 .

- Patrick Breuer: Patrice Lumumba - Heart of Africa. Asaro Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-941930-94-0 .

- Aimé Césaire : In the Congo. A piece about Patrice Lumumba. With an essay by Jean Paul Sartre . Transferred from Monika Kind. Quarthefte, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 1966 (French original: Une Saison au Congo. Editions du Seuil, Paris 1966)

- Aimé Césaire : Season in the Congo , transl. Heiner Müller , in: Joachim Fiebach (Ed.): Pieces of Africa , Berlin (GDR): Henschel, 1974, 347-420, as well as in: Heiner Müller, The Pieces 5: The Translations (Works 7), Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2004 , 167-247

- Matthias De Groof: Lumumba in the arts. Leuven University Press, Leuven, ISBN 978-94-6270-174-8 .

- Ludo de Witte: Government commission murder. Forum, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-931801-09-8 .

- Emmanuel Gerard, Bruce Kuklick: Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba. Harvard University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-674-72527-0 ( Table of Contents )

- (Review in: The Spectator, March 7, 2015 [1] )

- Thomas Giefer: Colonial-style murder. In: Heribert Blondiau (Ed.): Death on order , Ullstein, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-550-07147-7 , pp. 143-174.

- Jean Omasombo: Lumumba, Patrice Emery. In: Dictionary of African Biography . Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2021 from Oxford Reference (Restricted Access)

Web links

- Literature by and about Patrice Lumumba in the catalog of the German National Library

- The violent death of Patrice Lumumba Article by Bill Vann

- Colonial - Style Murder TV documentary by Thomas Giefer , 3sat, 2000.

- Photos from Lumumba website of journalist D'Lynn Waldron (English)

- Friederike Müller-Jung: Congo and the Lumumba murder case . Report from January 16, 2016 in Deutsche Welle at www.dw.com (German)

- Alexander Behr: Congolese independence hero - The deadly courage of Patrice Lumumba , Deutschlandfunk Kultur , January 13, 2021.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b South African History Online : Patrice Émery Lumumba . on www.sahistory.org.za (English)

- ↑ Reymer Klüver: The last days of Patrice Lumumba , in: GeoEpoche: Afrika 1415–1960, number 66, 2014, pages 140–151, quotation page 144.

- ^ Munzinger-Archiv GmbH, Ravensburg: Patrice Lumumba - Munzinger Biographie. Retrieved September 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Torben Gülstorff: Trade follows Hallstein? German activities in the Central African region of the Second Scramble . Berlin 2016, urn : nbn: de: kobv: 11-100241664 .

- ↑ Gerard Colby, Charlotte Dennet: Thy Will be Done. The Conquest of The Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil. HarperPerennial, 1996, ISBN 0-06-092723-2 , pp. 325-327

- ↑ a b Daniel Stern: Eisenhower's toothpaste. CIA in the Congo. In: WOZ The weekly newspaper . August 5, 2007, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Scott Shane: Lawrence R. Devlin, 86, CIA Officer Who Balked on a Congo Plot, Is Dead. In: The New York Times . December 11, 2008, accessed February 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Larry Devlin. CIA chief in the Congo whose death-defying exploits helped secure American influence in Africa. In: The Daily Telegraph . December 31, 2008, accessed February 5, 2016 .

- ^ Ronald Segal: Political Africa. A Who's Who of Personalities and Parties . Frederick A. Praeger, New York 1961, p. 160

- ^ South African History Online: Patrice Lumumba, former Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is shot . on www.sahistory.org.za (English)

- ↑ UN News: Character Sketches: Patrice Lumumba by Brian Urquhart . at www.news.un.org (English)

- ↑ Documents of the Belgian commission of inquiry (at the end of the page there are three documents in English)

- ↑ Report Reproves Belgium in Lumumba's Death The New York Times, November 17, 2001 (English).

- ↑ http://www1.wdr.de/themen/archiv/stichtag/stichtag1532.html

- ↑ Gerard Colby, Charlotte Dennet: Thy Will be Done. The Conquest of The Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil. P. 328

- ^ German edition CIA. The whole story , Frankfurt / Main 2008, pp. 225–227

- ↑ Lumumba murder: Son announces lawsuit against twelve Belgians. In: derStandard.at. June 22, 2010, accessed December 3, 2017 .

- ↑ 60 years after the murder: Belgium wants to clarify the death of the freedom idol Lumumba at focus.de, December 13, 2012 (accessed on December 13, 2012).

- ^ Belgian Prosecutor's Office investigates murder of Patrice Lumumba , rapsinews.com, December 13, 2013, accessed November 3, 2013

- ↑ Jean Shaoul: Britain's involvement in assassination of Congo's Lumumba confirmed , World Socialist Web Site, April 18, 2013, accessed November 3, 2013

- ↑ Leo Zeilig: Patrice Lumumba: Africa's Lost Leader , HopeRoad, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-908446-02-2 , preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ La pensée politique de Patrice Lumumba, textes et documents recueillis et présentés par Jean Van Lierde ( Memento of January 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Paris / Brussels 1963, Ed. Presence africaine

- ↑ Peoples' Friendship University: Foundation and History ( Memento of November 17, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ A memorial and its history kreuzer-leipzig.de, February 1, 2011

- ^ Page on the Poll Art Foundation , accessed on March 18, 2020

- ^ Page of the German-African Society (DAFRIG) Leipzig eV , accessed on March 18, 2020

- ↑ LoNam Verlag page , accessed on March 18, 2020

- ^ Paul Dessau: Requiem for Patrice Lumumba at requiemsurvey.org, accessed on December 17, 2013

- ^ Paul Dessau: Requiem for Lumumba (1964) ( Memento from December 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Schott Music, accessed on December 17, 2013

- ↑ Tod Lumumbas , Peter Hack's Society, accessed August 13, 2017

- ↑ Michael A. Cohen: Politics vs Drama in O'Brien's "Murderous Angels" (= Contemporary Literature . Vol. 16, No. 3 ). University of Wisconsin Press, 1975, pp. 340-352 , doi : 10.2307 / 1207407 , JSTOR : 1207407 .

- ↑ Ernstpeter Ruhe: Une œuvre mobile. Aimé Césaire dans le pays germanophones (1950–2015) . 1st edition. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8260-5787-8 , p. 233-234 .

- ↑ Lumumba - Death of the Prophet in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Lumumba in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Andrea Böhm: Lumumbas Martyrium. In: Die Zeit No. 16, January 13, 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ Fidel, the Che and the African Odyssey. (No longer available online.) Arte.tv, archived from the original on April 23, 2008 ; Retrieved November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Birgit Morgenrath: SWR2 Knowledge: An international conspiracy , swr.de, 2006, accessed on November 3, 2013

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lumumba, Patrice |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tawosa, Tasumbu (maiden name); Lumumba, Patrice Émery (full name) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Congolese politician and first Prime Minister of the independent Congo |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 2, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | at Katako-Kombé (Kasai) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 17th January 1961 |

| Place of death | Katanga state |