Planning of the Vienna Ringstrasse

From 1858 the city fortifications of Vienna were demolished and the Vienna city expansion was carried out. The Ringstrasse and Franz-Josefs-Kai were laid out and 850 buildings were erected. In contrast to other cities, the city expansion was not planned by a single person or institution. Rather, it took place through decades of planning, rescheduling and optimization by many actors, with chance also playing a major role.

prehistory

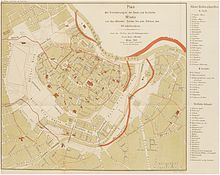

The city of Vienna has been surrounded by city walls since the early Middle Ages , which made expansion of the city impossible and led to housing shortages. On average, 37 people lived in each house in 1827, compared with 54 in 1857; that year the city had 471,442 inhabitants. The dense development also meant that there was not a single green space within the city walls. By razing the city fortifications, a large area would be available for development on the glacis. The glacis had an area of exactly 2 million m²; 1.3 million m² of this were green and open spaces, 533,000 m² traffic areas, 74,000 m² built-up areas, and 96,000 m² was the Vienna River. The width of the glacis was between 280 m and 450 m.

Plans for an expansion of the city of Vienna emerged as early as the 18th century. In 1716, the Englishwoman Mary Wortley Montagu wrote in a letter: " If the emperor thought it appropriate to have the city gates closed and to unite the suburbs with Vienna, he would have one of the largest and most beautiful capitals in Europe ". From the 1810s onwards, various experts created detailed projects for a city expansion, including Archduke Johann in 1825 . The glacis was to be built, but the razing of the city walls was not yet considered. That changed after the revolution of 1848 : the city fortifications had turned out to be a major obstacle to suppressing the revolution.

Between 1839 and 1856, the architect Ludwig Förster developed eight projects for city expansion. During the same period, plans were drawn up by Carl Roesner , Paul Sprenger , Leopold Ernst and Anton Ortner. From 1850 onwards, numerous commissions met, but they came to no results. The main reason for this was the permanent conflict between the military authorities on the one hand and the civilian Council of Ministers, which blocked each other. The Vienna City Council did not take part in the dispute, but only decided to beautify the glacis.

Even before the city was expanded and the Vienna Ringstrasse was built, its first building, the Votive Church, was built . On February 18, 1853, Emperor Franz Josef escaped an assassination attempt . Shortly afterwards, a brother of the emperor, Archduke Ferdinand Max (who later became Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico), developed the idea of having a "votive church" built as a votive offering . The people should raise the costs through donations. The plan met with general approval, and a building site was immediately sought; Places at the Belvedere, the Getreidemarkt , the Danube Canal and others were considered.

At that time, the architect Ludwig Förster worked tirelessly on his own initiative on plans for a city expansion. He suggested that the new church be built on the Glacis. In May 1855 Heinrich Ferstel received the order to build the church and he received permission to choose a building site on the Glacis himself. His choice fell on an area in front of the Schottentor , between Alser Strasse and Währinger Strasse . On October 25, 1855, the emperor approved the construction, although there was a military construction ban on the glacis; this was canceled retrospectively on February 25, 1856. The construction of the Votive Church in the restricted area was a prejudice that decisively weakened the position of the military.

In 1856 the construction of the votive church began. In the same year, Philipp Draexler von Carin , head of the Obersthofmeister -Amtes, published plans for the construction of a new court theater and a new court opera on the Glacis.

The original plan was to erect a large monument to Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff in front of the Votive Church . In 1876, the City Expansion Fund donated the space in front of the Votive Church to the City of Vienna so that it could create a green area with the memorial in the middle. The green space was laid out, but the Tegetthoff memorial was ultimately erected on the Praterstern. In later years, critics complained that the forecourt was too spacious, which made the Votive Church look a bit lost.

City expansion

In 1850 the suburbs up to the Linienwall and the Leopoldstadt were incorporated into Vienna. This made the city fortifications even more of an obstacle between the inner city and the new, surrounding districts. As a result, Interior Minister Alexander von Bach decided to force the city expansion in a flash. Recognizing the importance of public opinion, Bach first launched numerous newspaper articles criticizing the shortage of space in Vienna and the senselessness of the glacis. At the beginning of 1857, Bach succeeded in persuading Emperor Franz Josef to radically expand the city, although the strictest confidentiality was initially agreed. Bach was right to fear that if the project became known too early, some politicians and the military would boycott his plans.

In 1857 the main features of the ring road construction were laid down in a small circle. The demolition of the city fortifications should begin at the Schottentor and continue from there in both directions. A total width of 40 fathoms (75.9 meters) was determined for the grand avenue to be created. It was also determined which public buildings were to be erected, although this plan was later heavily modified.

It was also discussed whether Jews were allowed to purchase land in the Ringstrasse zone. Since Alexander von Bach had close ties to the Jewish Todesco family , he advocated this; In 1860 a law was passed on the admission of Jews to property.

Finally, Bach drafted a letter in which the emperor ordered the demolition of the city fortifications and the construction of the ring road. Franz von Matzinger , a close colleague of Bach in the Ministry of the Interior, got the actual wording . The “handwriting”, which officially comes from the emperor and is addressed to Bach, was published on December 25, 1857.

The demolition of the city fortifications is ordered in handwriting. Furthermore, the construction of a number of public buildings is explicitly mentioned: an opera house, an imperial archive, a library, a “town house”, a military general command, a city command and unspecified museums and galleries.

The competition

Immediately at the beginning of 1858, the “Concurs” was prepared, the name for an architectural competition at the time. The invitation to the competition was published in the Wiener Zeitung on January 31, 1858 . At the same time, work began on precisely measuring the glacis. The first competition entry arrived on March 2, 1858, and 85 projects were submitted in the following months. Well-known architects as well as amateurs took part. All projects were publicly exhibited in the fall of 1858.

The jury met on October 27, 1858. It consisted of

- Major General Julius von Wurmb from the Military Chancellery,

- Ministerialrat Franz Thun from the Ministry of Education,

- Section Councilor Valentin Streffleur from the Ministry of Finance,

- Government Councilor Eduard Hohenbruck from the police,

- Privy Councilor Hermenegild von Francesconi from the railways,

- Anton Edler von Dück from the Chamber of Commerce,

- Castle captain Joseph Lang from the court authorities,

- Professor Rudolf Eitelberger from the Academy of Fine Arts ,

- Ministerialrat Joseph von Lasser from the Ministry of the Interior,

- Section Councilor Franz Matzinger from the Ministry of the Interior,

- Section Councilor Moritz Löhr from the Ministry of Commerce,

- Lieutenancy Council Franz von Žigrovič from the Lower Austrian Lieutenancy,

- Mayor Johann Kaspar von Seiller of the municipality of Vienna,

- City building department adjunct Joseph Melnitzky from the municipality of Vienna,

- Architect Leopold Ernst ,

- Architect Heinrich Ferstel ,

- Architect Theophil Hansen ,

- Architect Johann Romano and

- Court architect Anton Ölzelt .

The jury examined all projects in the following weeks, whereby the submitters remained anonymous. In project no. 51, the street to be laid around the city center was called “Ringstrasse”, which was immediately popular. Project 59 was discussed particularly intensively, and the jury also liked it. Since Ludwig Förster had already drawn up plans for a city expansion, it was easy to guess his authorship. The jury also liked project No. 85 - after all, it came from jury member Moritz Löhr. Project no. 53 came from the jury member Streffleur.

On December 11, 1858, the jury published its decision. She had not been able to commit to a winner, but awarded three first places, namely to Ludwig Förster, to Friedrich August von Stache as well as to the team Sicardsburg and van der Nüll . The proposed building density was very different for the individual projects. The victorious Sicardsburg / van der Nüll team suggested the densest construction, only 12.3% of the green area was planned. Most of the green space, 37%, was proposed in the sixth-placed project by Peter Joseph Lenné , the director of the Prussian court gardens in Berlin. In this project, instead of the ring road, several sidewalks would have been created, which meandered through gardens.

From January 17, 1859, the winners and numerous officials came together several times to merge the three designs. This did not succeed, but all three award winners modified their plans and moved closer to each other. On this basis, the Ministry of the Interior drew up a plan that was presented to the emperor on May 17, 1859. In this “basic plan”, the width of the ring road was set from the original 40 to 30 fathoms (56.9 meters) for economic reasons. Due to the war in Northern Italy , the emperor did not reply until September 1, 1859. The emperor did not like one detail in particular: Friedrich August von Stache's winning project planned the Rossau barracks where the Schottenring is today. Emperor Franz Josef wanted the Ringstrasse to be led to the Danube Canal. After fulfilling this and a few other wishes, the plan for the expansion of the city received imperial approval on October 8, 1859. The basic plan was still strongly influenced by military considerations. Eight barracks were to be located within 2,000 meters of the Hofburg.

Interior Minister Alexander von Bach had previously been the driving force behind the construction of the Ringstrasse. In the summer of 1859 Austria lost the battles of Magenta and Solferino , and subsequently the war, which led to political shock. Several members of the government were dismissed, including Interior Minister Bach on August 21, 1859. The management of the city expansion passed to Joseph von Lasser and Franz von Matzinger.

The urban expansion fund

To administer the city expansion, a city expansion commission was founded in December 1859 , the most influential member of which in the following years was Section Councilor Franz von Matzinger. In 1858, Franz von Matzinger created the city expansion fund to exploit the grounds and finance the public buildings; its first president was Matthias Constantin von Wickenburg . This fund was an institution under public law and not part of the state's assets, it was also not allowed to be controlled by the audit office. It was soon well endowed, and in the following years both the Ministry of Finance and the City of Vienna tried to get some of the money, but without success.

The Glacis grounds had been the property of the Vienna Genius Directorate of the Army since 1817 . On May 14, 1859, ownership of this area was transferred to the City Expansion Fund. However, the parade and parade ground between today's Universitätsring and ladenstrasse remained with the military and was not allowed to be built on. The ownership of the bastions was gradually transferred after they were evacuated by the military. The first to come into civilian possession were the bastions on the Danube Canal in spring 1858, the last to be the Dominican bastion and the beaver bastion in 1865. A large area at the Wasserkunstbastei was transferred to the municipality of Vienna on November 7, 1860 by imperial order to create the city park .

The city expansion was designed as a profitable company from the start. An area of 640,600 m² was to be built, of which 73.7% private buildings, 13.8% public buildings, 8.2% military buildings and 4.3% market halls. 566,000 m² of green areas were planned - including the military parade ground - that is 18.7% of the expansion area (in fact it was 20%). Not a single church building was planned in the urban expansion area, and none was actually built. (The Votive Church already existed before the Ringstrasse was built.)

Financing through a fund brought the municipality of Vienna to the scene. She realized that she would not have any share in the income from property sales, but that she would have to finance the infrastructure of the new districts - traffic routes, water and gas pipes, sewerage. In January 1860, Vice Mayor Andreas Zelinka made the offer to buy the Glacis grounds for 12 million guilders; the municipality of Vienna would then use them itself. Interior Minister Agenor Gołuchowski , Alexander von Bach's successor, strongly opposed the community's plan. He caused the emperor to order the original concept of funding through funds on April 29, 1860. The exploitation of the Glacis grounds then brought in 112 million guilders by 1914.

The city of Vienna was the economic loser of the city expansion and had to take on large debts because of the costs of the infrastructure. The city expansion fund was very rich after a short time and consequently powerful, while the municipality of Vienna could only exert very little influence on the planning of the ring road zone, except in its final phase.

The demolition of the city fortifications

The demolition of the city walls at the Rotenturm Gate began on March 29, 1858, under the direction of the engineer Franz Wilt. The first bastion to be demolished was the parlor bastion in 1858, the last the Löwel bastion, the removal of which continued until 1875. The demolitions were carried out by private companies; they progressed relatively quickly, as explosions with gunpowder and gunned cotton were used. A total of 913.00 m³ of material was moved; the costs amounted to 1,282,512 guilders (approx. 11.3 million euros). The bricks and stones obtained during the demolition work were sold, which brought in 380,368 guilders (approx. 3.3 million euros) for the city expansion fund. Only the castle gate and those parts of the fortifications on which the Franz Josefs barracks stood were not demolished; these were not canceled until 1900.

On the occasion of the annual Prater tour, Emperor Franz Josef drove through the breach that had now emerged at Rotenturmstrasse on May 1, 1858 . He formally opened the road to be redesigned along the Danube Canal, which was named Franz-Josefs-Quai . To finance the demolition, the Ministry of Finance gave the City Expansion Fund a loan of 303,000 guilders (EUR 2.7 million), which was quickly repaid after the first sales of building land.

When the Mölker Bastei was demolished , a slope down to the level of the Ringstrasse was created in front of the group of houses to which the Pasqualati House belongs. A retaining wall was built in 1871 to secure this slope. The same happened after the demolition of the Braun bastion in front of the Palais Coburg . And even after the Augustinian Bastion was demolished , a retaining wall was built along Hanuschgasse. These brick walls are sometimes mistaken for remnants of the city fortifications.

The planning

Planning the road

Construction of the actual ring road began in the spring of 1860. It was decided to lay it out as a double avenue based on the Parisian model with many trees; after all, the Viennese were used to the shady avenues of the Glacis. The still usable trees on the glacis were dug up and used for the ring road zone. For a long time there was disagreement about the types of trees to be planted. There was only agreement on the rejection of the horse chestnut, since it is common in Vienna and therefore too " plebeian ". They finally agreed on plane trees and trees of the gods (which later did not prove themselves).

In the spring of 1861, the leveling of the previously uneven surface began. Despite its name, the ring road is not ring-shaped, but consists of six straight segments. This made the construction of the road network easier, and it satisfied the military who wanted free lines of fire along the roads.

The cross-section of the street was determined on November 22, 1860. The center lane should be 10 fathoms (19 meters) wide, flanked by two alleys, two side lanes and two sidewalks. The arrangement of Reit-Alleen was discussed without result; the officials were against it, the military for it. There were numerous protests against the planned cross-section of the street. Finally, the width of the central carriageway was reduced from 10 to 8 fathoms (17.1 m), flanked by 3.5 fathoms (6.6 m) wide avenues and 4 fathoms (7.6 m) wide secondary lanes. As part of a celebration, Emperor Franz Josef officially opened the (still unfinished) Ringstrasse on May 1, 1865. The Franz-Josefs-Kai was also completed in the same year. The construction of the ring road lasted until the end of 1870; the width of the individual tracks was changed in later years.

The planning of Schwarzenbergplatz

In 1861 Emperor Franz Josef decided that a monumental equestrian monument should be erected for the general Karl Philipp zu Schwarzenberg , which raised the question of its location. The plan to place the monument on Stephansplatz was quickly rejected. Finally, Section Councilor Moritz Löhr suggested creating a space for the memorial between the Kärntner Ring and the Schubertring. He planned the square in a circular shape, with trees. The location was appealing, but not the execution: the green trees would rob the bronze statue with its green patina . Franz von Matzinger was unhappy because the round square would result in the loss of profitable building land, and ultimately Schwarzenbergplatz was then laid out in a rectangular shape from 1865 on and without trees.

The planning of private buildings

Most of the new buildings to be erected should be private buildings, especially apartment buildings. The urban expansion area was divided into building blocks using a grid of streets. In the original plan, 128 building blocks were envisaged; in fact there were 135. Most of the blocks are between 2,000 and 4,000 m² in size. In the building regulations for the imperial capital and residence city on September 23, 1859 a building height "up to the roof hem" ( eaves height ) of 13 fathoms (24.7 meters) was standardized. Taking this height into account, the client was free to choose the number of floors.

The first completed building of the city expansion was the Treumann Theater at today's address Morzinplatz 4 in 1860. It was made of wood and burned down in 1863. (The Hotel Metropol was built in its place in 1873 and the Leopold-Figl-Hof in 1968. ) In 1860, more houses were built around the future opera and in the Franz-Josefs-Kai / Heinrichsgasse area.

On December 21, 1860, the municipal council established the center of the Ringstrasse as the boundary of the 1st district. This led to protests by a number of builders, as their plots outside the Ringstrasse would now be in the less prestigious “suburb”. The local council gave in and now set the road as the district boundary.

In order to be able to block the area west of the opera, Archduke Albrecht , owner of the Palais Archduke Albrecht , had to be compensated. He owned buildings south of his Albertina, including his stables, which would be annoying in a residential area by smell and noise. Finally, the city expansion fund bought the property from the archduke for 400,000 guilders (approx. 3.5 million euros). The Goethegasse and Hanuschgasse were immediately laid out and prepared for construction.

After the demolition of the city fortifications, the area around the Volksgarten was uneven. It was decided to enlarge and level the previously much smaller Volksgarten up to the Ringstrasse, which was completed in October 1863.

Planning the opera

Since both the theater at Kärntnertor and the kk Hoftheater at Michaelerplatz were too small and no longer up-to-date, the construction of a new opera house was urgent. It would have made sense to build the imperial court opera near the Hofburg. Nonetheless, Alexander Bach and the architect van der Nüll decided very early on for a place in front of the Kärntnertor. Bach's opponents suspected that the power-conscious interior minister wanted to withdraw the opera house from the imperial court by means of the spatial separation and convert it into a state opera - which actually happened some time later, albeit not through Bach. The opera was one of the few public buildings on the Ringstrasse that were actually built where they were planned.

Because of the narrowness of the existing theaters, the preparatory work for the opera began hastily, even before the Ringstrasse existed. As a result, the streets around the opera later had to be dug by more than a meter, otherwise water would have penetrated the opera when it rained. A major disadvantage of the chosen location was that no representative square could be created in front of the opera house. The situation later got worse when the huge Heinrichshof optically overwhelmed the opera.

The planning of the Heinrichshof

The first parcelling of land on the Glacis began in 1860, and on May 23, the Wiener Zeitung announced that the first property sales would soon be imminent. In the plans approved by the emperor, it was planned to build up the area inside the Ringstrasse first, and only then the outside area. But as early as April 1859, the entrepreneur Heinrich Drasche applied to acquire six parcels across from the future opera; in May 1860 he received it. From 1861, Drasche built the monumental Heinrichshof on his plots . Due to this prejudice it was possible to build on both sides of the ring immediately.

The planning of the parliament building

In 1861 Minister of the Interior Gołuchowski overthrew and was replaced by Anton von Schmerling . His February patent from 1861 provided for the formation of a Reichsrat as a representative body . As a result, two representative buildings had to be planned on the Ringstrasse, a mansion and a House of Representatives . Since its construction would take several years, a provisional wooden parliament building was built by the architect Ferdinand Fellner at the Schottentor, at today's addresses Währinger Strasse 2-6 . After the extremely short construction period of six weeks, it was completed on April 26, 1861. Satirists like to call the building the Schmerling Theater .

The construction of the final parliament building was to begin as early as 1862, at the Augarten Bridge. Then the start of construction was postponed to 1863 and the construction site on the extended Operngasse. Finally, in 1864 it was agreed to build the House of Representatives on a plot of land at today's Schillerplatz, and the manor house in the area of today's Schmerlingplatz.

The planning for the castle gate

When the city fortifications were demolished, all city gates were demolished, with the exception of the castle gate . It was logical to remove this now pointless structure, and that was also considered. Theophil Hansen, on the other hand, suggested converting the castle gate into a victory memorial. After long discussions, no decision could be made, neither for demolition nor for renovation. The gate just stopped.

The planning of the town hall

Since the construction of a new town hall was urgent, plans were made as early as 1858. After Mayor Andreas Zelinka was the initiator of the city park , he wanted to have his town hall close by. After years of negotiations, the municipality of Vienna bought a large plot of land on the future Parkring, between Johannesgasse and Weihburggasse, from the city expansion fund. The next few years passed with debates about the construction program. Finally, in 1869, an architectural competition was held, which Friedrich von Schmidt won with a neo-Gothic design. The local council agreed almost unanimously to a rapid start of construction.

Planning the stock market

In 1862 the kk Börsenkammer intended to build a new stock exchange building and asked the City of Vienna to give it a piece of land. Since the Salzgries barracks had already been demolished and the police station on Salzgries was also to be demolished, this area (today's Rudolfsplatz) was the ideal choice. Heinrich von Ferstel drew up a corresponding concept in 1863, and in 1865 the building site was purchased. However, the Chamber of Commerce wanted to reside directly on the Ringstrasse and succeeded in exchanging its building site for the one that was intended for the “town house” on the Ringstrasse. Theophil Hansen began building the stock exchange in 1874. (The town house was not built and Rudolfsplatz was later converted into a park.)

Planning the museums

The area around the castle gate was considered a particularly important place due to its proximity to the imperial castle. Both in the context of the architectural competition and afterwards, a very large number of suggestions for its construction were made. In the “basic plan” approved by the emperor, the (today's) Heldenplatz was to be flanked by the imperial court building and the imperial court library. Two military buildings were planned outside the Ringstrasse, the Imperial Guard and the Imperial General Command.

In 1862, the architect Moritz Loehr suggested building two museums for the imperial collections on the square in front of the castle gate. Franz von Matzinger suggested designing one of the museums as an art museum and the other as a natural history museum. The City Expansion Commission liked this plan, and on September 23, 1864, the Kaiser approved the project. The monarch also stipulated that the line of sight to the court stables should not be impaired.

The architectural competition began in 1866. Due to the opaque and personal relationships in Vienna, only four architects were invited, namely Moritz Loehr, Carl von Hasenauer , Theophil Hansen and Heinrich Ferstel . A jury decided in 1867 that none of the designs would be suitable for execution. Loehr and Hasenauer were asked to revise their drafts and submit them again. Ferstel and Hansen felt set back. As a result, a violent architectural feud that lasted for years broke out and was exploited intensively by the media. Finally, Ferstel and Hansen were also allowed to revise their projects. But both were cold and refused. The modified designs by Loehr and Hasenauer were evaluated by a jury in 1868, which then did not make a decision.

Some commentators saw the problem in the fact that the competition had started with a “friendship economy” from the start. As a solution after three years of confusion, the decision was made in 1869 to bring in an external expert, the German architect Gottfried Semper .

The planning of the Kaiserforum

Up to this point, the design of the two museums had been discussed unsuccessfully for three years. In contrast, Semper developed a much more comprehensive solution in 1869 that integrated the entire space in front of the Hofburg. With two new wings of the Hofburg, the two museums and the court stables, a monumental, closed square would arise, which Semper called the “Kaiserforum”. The building complex was 500 × 300 meters in size. With this solution, Hasenauer's designs would be well suited for museums. The Kaiserforum was not just Semper's idea: in the winning Sicardsburg and van der Nüll project in 1858, the buildings were already arranged in exactly the same way, but they had a different function.

In August 1869, Semper and Hasenauer were commissioned to build the Kaiserforum. Their construction plans were completed at the end of 1870. The emperor set Semper's salary at 5,000 guilders (approx. 44,000 euros) per year. Construction of the two museums began on November 27, 1871. Since the Hofburg wing opposite the Neue Burg was never built, the Imperial Forum remained incomplete.

The committee formed for museum construction had already decided in 1866 to create the space between the museums in the French style and without trees. The park was not created until 1884 and was named Maria-Theresien-Platz after the Maria-Theresien-Monument was erected in 1888 .

Planning the New Castle

In order to realize the Imperial Forum, two new wings were to connect the Hofburg with the museums. These two wings were to be connected by a wing that was to be built in front of the Leopoldine wing. The construction of the south-eastern wing, today called Neue Burg , began in 1881 under the direction of Hasenauer. The building did not meet the taste of the emperor, who found it too monumental. In addition, there was little need for the new wings. On April 12, 1913, the emperor decided to abandon the construction of the planned wing.

The planning of the Burgtheater

The new construction of the Burgtheater was planned from the start as part of the city expansion, but no space had yet been determined. Gottfried Semper suggested treating it as part of his Imperial Forum and leaning it against the newly built western wing of the Hofburg. The emperor did not like this, however, and suggested that the theater be built in the Volksgarten.

Shortly afterwards, the plan was born to move the theater further away from the Hofburg and to place it right in front of the town hall. Semper immediately voted for this plan, but Franz von Matzinger was against it. As President of the City Expansion Fund, he was careful about thrift; and at the proposed building site there were houses (at today's Löwelstrasse and Teinfaltstrasse) that would have to be removed and demolished. However, the City of Vienna was enthusiastic about the new proposal, as the area in front of the town hall would be upgraded and form an ensemble with the Burgtheater. The municipality of Vienna therefore paid 250,000 guilders (approx. 2.2 million euros) from its own funds for the replacement of the disruptive houses, and in December it was decided to build the Burgtheater . So that the theater shouldn't look too thin compared to the large town hall, Semper built two large wings on its sides, which more than double the width of the building.

The planning of the Volksgarten group

After some houses had been demolished for the construction of the Burgtheater, the area behind had to be cleaned up. In 1872 the idea arose to reduce the size of the Volksgarten and to build a building behind the Burgtheater. Semper and Hasenauer planned a group of houses that would merge into one very large building. This so-called “Volksgartengruppe” had arcades and offered plenty of space for shops, restaurants and galleries. Hasenauer prepared detailed plans in 1875/76. The house would have been one of the grandest buildings on the Ringstrasse. The city expansion fund predicted it would be an economic success.

Mayor Cajetan Felder protested violently against the downsizing of the Volksgarten and received the support of several prominent aristocrats. Finally, the emperor walked to the area at the former Löwelbastei and after this visit prohibited the public garden group.

The planning of the ring theater

With a view to the world exhibition in 1873 , a public limited company was established in 1872 with the aim of building a popular theater. For this purpose, a plot of land at Schottenring 7 was rented by the urban expansion fund and architect Emil Förster was engaged for the planning. Since the building site was relatively small, but the theater was to hold 1,700 spectators, Förster designed a tall, slim theater with four balconies. He reduced the width of the staircases to a minimum. The corporation commissioned Gottfried Semper to examine the plans, and he gave his approval. Construction began in February 1872. (The Ringtheater fire then destroyed the building in 1881. )

Planning the university

During the revolution of 1848 the main building of the Old University on Jesuitenplatz (today Dr.-Ignaz-Seipel-Platz ) played an important role. As a result, after the revolt was put down, it was occupied by the military and ceded to the Academy of Sciences in 1857 . University operations were temporarily relocated to other buildings. In 1854, Minister of Education Leo von Thun and Hohenstein planned the construction of a new university building on Rossauer Glacis, at the beginning of Währinger Straße or today's Günthergasse. At this point there was an abandoned rifle factory. Thun commissioned the architects Sicardsburg and van der Nüll to design the new building, which was then decided in 1855. The authorities also liked the location because the unpredictable students would not make the Ringstrasse unsafe, but only the Alsergrund.

In the meantime, however, the building site for the Votive Church had been marked out and in the way of the university. Sicardsburg and van der Nüll redesigned and planned a university building behind the choir of the Votive Church. The style was based on the Gothic to fit the Votive Church. In 1858 the plan and its immediate implementation were decided. In 1859 construction could not be started because of the war in northern Italy and in 1860 Thun left the government, which brought the project to a standstill.

The project was increasingly criticized. Heinrich Ferstel in particular protested violently against the fact that a second monumental building should compete with his votive church. In contrast, the Alsergrund district council fought for the prestigious project in their district. Years of discussion were the result.

The planning of the town hall district

In the course of the city expansion, there were permanent conflicts between the military and the Ministry of the Interior. The civil officials tried again and again - and mostly successfully - to prevent the construction of military structures on the Ring. The basic plan approved by the emperor provided that several military buildings were to be built at the expense of the city expansion fund. In 1863, however , Minister Lasser made a deal with the military: the fund paid the War Ministry a lump sum of five million guilders; In return, the War Ministry had to finance its military buildings itself.

After the lost wars of 1859 and 1864 and after the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866, the army had to be reformed and modernized, which meant a lot of money was needed. As a result, the War Ministry thought about the sale of land, including the 210,000 m² parade and parade ground on the Ring. The process was accelerated when a downpour broke out during a parade in 1868 and the emperor and his entourage were stuck in the mud, which did not amuse the chief warlord. Taking advantage of the opportunity, the municipal council suggested on August 5, 1868 the abandonment of Paradeplatz, which the emperor approved on August 17 with remarkable speed. The military offered the area for sale in autumn 1868, whereupon a bank, an investor consortium and the municipality of Vienna quickly applied. The war ministry demanded 6 million guilders (53 million euros) for the area, which was too expensive for anyone interested.

In the winter of 1868/69, Mayor Cajetan Felder gave birth to the idea of having three monumental buildings erected on the parade ground, the parliament, the town hall and the university. The plan was immediately appreciated. It was also immediately decided that Theophil Hansen would build the parliament and Heinrich Ferstel the university - both of them were deeply offended after the architects' war over the museums and had to be appeased. As the architect of the town hall, Friedrich Schmidt was also already certain as the winner of the relevant competition.

The matter was delayed, as it was now questioned whether the military even legally owned the land and whether it was not state property and therefore belonged to the Treasury. Supported by the emperor, who wanted to get rid of the Paradeplatz, Franz von Matzinger was finally able to work out a solution in July 1870: his city expansion fund bought the site and paid 3.5 million guilders to the war ministry and 1.5 million guilders to the finance ministry.

The new planning of the town hall

The construction of the monumental buildings on Paradeplatz was Cajetan Felder's idea, and of course he placed his town hall in the middle of the ensemble. However, this also made sense for aesthetic reasons, as it was the tallest of the three buildings and this was the only way to achieve symmetry. The town hall was so big, however, that it was pushed back to Ladenstrasse so as not to visually overwhelm the Ringstrasse.

The city had already acquired a piece of land on Parkring for the construction of the town hall, but it was difficult to return it. Emperor Franz Josef solved the problem by ordering on June 11, 1870 that the city was allowed to exchange the old property for the new one on Paradeplatz at no additional cost. The new area was four times as large, so that a park could be created near the town hall .

The area behind the town hall and to the side of it was parceled out by the city expansion fund and sold to private customers. The rise in land prices was enormous. A few years earlier the military had asked for 300 guilders per square fathom and couldn't find a buyer, but 2,000 guilders were paid (approx. 4,900 euros / m²).

The construction of the town hall was delayed because there was initially disagreement about numerous details. It was discussed whether a chapel or a wine cellar should be built in. The chapel was rejected, the wine cellar decided. Finally, the laying of the foundations began in July 1872, and the foundation stone was laid on June 14, 1873.

Four monumental buildings in completely different styles were now projected on the former parade ground with the parliament, town hall, university and Burgtheater. In order to visually calm the town hall district, the city expansion fund laid down building regulations: all houses around the town hall had to be built with arcades , a design that had been rare in Vienna at that time. This gave the town hall district a harmonious appearance.

The new planning of the parliament building

The original plan was to build two separate buildings on the Ring for the two chambers of the Reichsrat. A lot of space was now available at the new location, and Theophil Hansen was commissioned to build a single, large building for both chambers (the House of Representatives and the Manor House). He submitted his design in 1872. The monumental construction in the ancient Greek style was costly, and Hansen had to expend a lot of energy to prevent a structural simplification of his building. The foundation stone was finally laid on August 31, 1874.

The area behind the parliament was built with residential buildings, with one exception: Prince Vinzens von Auersperg had complained bitterly in 1865 that an apartment building was being planned in front of his Palais Auersperg , and he threatened claims for damages. As a result, Schmerlingplatz was enlarged so that the square in front of the palace remained a green area.

The planning of the Palace of Justice

Since there was still free space at the edge of the Paradeplatz, it was decided to build a building for the Higher Regional Court, the Palace of Justice . It was supposed to be built by the architect Alexander Wielemans on Load Street opposite the Regional Court for Criminal Matters . The President of the Higher Regional Court did not like the location, so the building was moved to the southern edge of the area, to Schmerlingplatz; Construction began in 1875.

The planning of the Academy of Fine Arts

An art academy was not included in the original plans on the Ringstrasse. The Imperial and Royal Court Academy of Painters, Sculptors and Architecture had been housed in St. Annahof on Annagasse since 1786 . Rudolf Eitelberger , Austria's first professor of art history, proposed a new building of its own for the academy. The Minister of Culture and Education agreed, and a building site was quickly found. The building of the House of Representatives was originally supposed to be built on Schillerplatz. After the parliament was rescheduled to its current location, the Academy of Fine Arts got the property on Schillerplatz. The building was constructed by Theophil Hansen from 1872.

The new planning of the university

Although there was now a lot of space available at the parade grounds, several faculties wanted to hold onto the location on Alsergrund. Architect Ferstel had always opposed a monumental building next to his votive church; now that he was allowed to build the university , his protests became even more violent. Finally, Franz von Matzinger succeeded in establishing the new location on the Ringstrasse. When Ferstel's construction plans were published, the university management was pleasantly surprised by the size of the building; above all, the entire university library could now be accommodated in the main building. Construction began in 1877.

The planning of the parlor district

Historians like to divide the city expansion into three phases: In the first phase, the expansion was planned and the first buildings completed. In the second phase, the parade ground was abandoned by the military, which meant that important buildings could be built here. The third and final phase was made possible by the demolition of the Franz-Josephs-Kaserne . So far, this has made the construction of the Stubenring impossible.

In February 1890, Franz von Matzinger, President of the City Expansion Fund, retired at the age of 73. For more than 30 years he was the organizer of the city expansion and the construction of the ring road. He had always defended the millions in the fund like a lioness defending her cubs, as the Wiener Tagblatt noted, and had turned the city expansion into a profitable enterprise. A similarly competent successor could not be found, so that the fund lost power and instead the municipality of Vienna controlled the last phase of the city expansion.

The demolition of the Franz-Josephs-Kaserne, requested by many, was delayed. In the meantime, the Stubenviertel was planned. The brothers Rudolf, Karl and Julius Mayreder won the corresponding competition in 1892 . After opaque processes, however, the Vienna City Council commissioned the architect Otto Wagner with the project. The Mayreder brothers were consoled with projects to build the Vienna River.

Finally the military was ready to give up the barracks; but it will take a few years before an agreement can be reached on the financial compensation. The Franz-Josephs-Kaserne was then demolished in 1900. Otto Wagner had long since worked out the plans for the district: a grid-like residential area with Wagner's Post Office Savings Bank in the center. The military wanted to set up their new war ministry directly on the Stubenring . Otto Wagner wanted to build this too, and thus give the parlor district a uniform style. Archduke Franz Ferdinand declared, however, that he considered Otto Wagner too modern, while the architect Ludwig Baumann was much more suitable. In the architectural competition in 1908, Wagner's design was excluded from the competition for “formal reasons” and Baumann was declared the winner.

The Schottenring ends at the Rossauer Kaserne, which is a kind of end point. (Today the Ringturm fulfills this function much better.) The Stubenring, however, ended without a singing or sounding at Aspernplatz (since 1976: Julius-Raab-Platz ). There was a free space there. So it was a good thing that the syndicate Wiener Urania was looking for a building site for an adult education center and observatory. The striking building would be a good way to end the ring road to the east. On June 24, 1904, the local council decided to give Urania the building site at Aspernplatz for a symbolic annual rate of 10 kroner. On May 4, 1909, the foundation stone was laid for the Urania .

Planning the green areas

The "basic plan" of 1859 provided for numerous free areas, above all at the request of the military. Over time, however, the army lost its interest in erecting military buildings on the Ringstrasse; this meant that the open spaces provided there could be used for other purposes. The city expansion fund tried to create as much lucrative building land as possible, but also understood the city administration's desire for recreational areas. Between 1860 and 1914, 20 parks were built in the Ringstrasse zone:

Quaipark: The first urban park in Vienna was the Quaipark, also called Franz-Josefs-Park. City gardener Rudolph Siebeck laid out the park on behalf of the city council , the budget was 8,000 guilders (approx. 70,000 euros). The park was located on Franz-Josefs-Kai , between today's Schottenring underground station and the Salztorbrücke . Because of its not very lush tree cover, the Quaipark was popularly called "Beserl Park". This name was subsequently transferred to other not very attractive parks. In the post-war period, the park was partially destroyed by the construction of the B227 expressway ; his remnant is now used as a dog run area.

City park: In September 1860, the city expansion fund gave the City of Vienna free of charge an area of 94,000 m² to create the city park. The facility was opened to the public on August 21, 1862; the costs up to then amounted to 180,000 guilders (approx. 1.6 million euros). The municipality of Vienna wanted to expand the park to Schwarzenbergplatz in 1863, but both the Ministry of the Interior and the emperor refused.

Provisional park: In 1861 the provisional parliament building was erected at Schottentor, at today's address Währinger Strasse 2-6. Behind the building, at today's Wasagasse, the garden architect Lothar Abel laid out a (nameless) park for 4,000 guilders (approx. 35,000 euros). After the temporary construction was demolished in 1884, the area was built on.

Children's park: Also in 1861, the community received 51,000 m² on the right bank of the Vienna River, in the 3rd district, free of charge from the city expansion fund. The park was designed by Rudolph Siebeck and was completed May 3, 1863; the cost was 142,000 guilders (approx. 1.2 million euros). The facility was informally called the “Children's Park”, but is now considered part of the city park.

Resselpark: There was a lawn in front of the Imperial and Royal Polytechnic Institute on Karlsplatz for a long time. The urban expansion fund commissioned Rudolph Siebeck in 1864 to create the Resselpark here. In 1866 the city of Vienna succeeded in taking over the park.

Weghuberpark: The coffee maker Albert Weghuber planned in 1861 to keep part of the glacis as a green area. When he went bankrupt, in 1865 the city expansion fund handed Weghuber's “coffeehouse garden” over to the magistrate to create a children's playground. The area west of Museumsstrasse, between Lerchenfelder Strasse and Burggasse, was designed as a garden by the Neubau district for 1,668 guilders (approx. 15,000 euros). In 1887, the urban expansion fund asked for the southern part of the area back to make the construction of the German People's Theater possible. The green space not required for the theater was left as Weghuberpark.

Reserve garden: In 1865, the City of Vienna managed to enlarge the Stadtpark a bit in the direction of Schwarzenbergplatz. The urban expansion fund left around two hectares of land between the Wien River (today: Lothringerstraße) and the Heumarkt. The green area known as the “reserve garden” was designed by Lothar Abel and Rudolf Siebeck for 86,577 guilders (approx. 760,000 euros) and was completed in 1869. The reserve garden had - and still has - the task of growing most of the plants required for urban green spaces. The construction of the Wiental line of the Stadtbahn and the arching of the Wien River brought the end of the reserve garden in 1895. After the construction work was completed, the area was dedicated as building land; The Konzerthaus , the Vienna Ice Skating Club and the Hotel Intercontinental were later built here . The reserve garden was relocated to the Stuwerviertel in 1897 , and to the Donaustadt as the Hirschstetten flower garden in 1957 .

Schwarzenbergplatz: In 1869 the plan was to build up the southern part of Schwarzenbergplatz between Rennweg and Prinz-Eugen-Straße. Since Prince Friedrich von Schwarzenberg did not want any apartment buildings in front of his Palais Schwarzenberg , he bought the 4,500 m² area in front of his palace for 22,000 guilders (approx. 190,000 euros). In 1870 he had a generally accessible garden laid out there at his own expense; The high-jet fountain was built here in 1873 .

Rathauspark : In 1870 it was decided to create a 40,000 m² park in front of and next to the town hall. Initially there was heated controversy within the local council. Some of the councilors wanted - similar to the square in front of the Votive Church - as little planting as possible so that the beautiful town hall would be clearly visible. Another faction wanted a heavily planted recreation area and ultimately won. The park was laid out by the city building authority and the city gardener Siebeck, the budget was 165,380 guilders (approx. 1.5 million euros). On the day the foundation stone was laid for the town hall, June 14, 1873, the town hall park was completed.

Beethovenplatz: The green space on Beethovenplatz was given to the municipality of Vienna in 1873 on the condition that space was left free for the Beethoven monument; it was erected in 1880. Beethoven looked in the direction of the Stubenring and had the Vienna River at his back. The green space was laid out in the same year by Lothar Abel and the AC Rosenthal company for 3,800 guilders (approx. 33,000 euros). After the vaulting of the Vienna River, Beethoven was turned 180 degrees in the direction of the newly laid out Lothringerstrasse in 1901, which together with the redesign of the park cost 18,902 crowns (approx. 80,000 euros).

Börseplatz: At the interface between the existing inner city and the new ring road zone, it was originally planned to build a market hall. In 1870 it was decided to create a park instead. It was designed in 1879 by the young city gardener Ferdinand Maly, the cost was 10,841 guilders (approx. 95,000 euros).

Schillerpark: The residential buildings in the area of what will later become Schillerplatz were completed between 1870 and 1872, the Academy of Fine Arts in 1876. In front of the academy, a 6,800 m² open space was reserved to erect the Schiller monument. The monument was erected in 1876 and the park was laid out in 1877–1878.

Park in front of the Votive Church: In 1876, the City of Vienna's City Expansion Fund donated the 14,000 m² forecourt of the Votive Church under construction to erect the Tegetthoff monument . The park was built in 1879 by Lothar Abel and Ferdinand Maly, the cost was 42,920 guilders (approx. 380,000 euros). The memorial was finally erected on the Praterstern in 1896 . The park in front of the Votive Church was nameless for a long time; In 1984 the green area on the side was named the church in Votivpark and the area in front of the church in Sigmund-Freud-Park .

Schlickplatz: The military had originally insisted on having a clear field of fire from the Rossau barracks in the direction of the Ringstrasse. In the end, this area around Kolingasse was built, with the small Schlickplatz remaining as a small remnant of the military “defile space”. It was designed as a park by Ferdinand Maly from 1879 to 1880.

Maximilian-Platz: Only after the building behind the Votive Church had been completed was a green area laid out there in 1882. It was called Maximilian Platz until 1920 (the emperor's brother had initiated the Votive Church), 1920–1934 Freiheitsplatz, 1934–1938 Dollfussplatz , 1938–1945 Hermann-Göring- Platz, 1945–1946 again Freiheitsplatz and since 1946 Roosevelt Platz .

Schmerlingplatz: Since the Franzensring (today: Dr.-Karl-Renner-Ring) makes a bend in the direction of the Burgring after Parliament, the construction was difficult. The problem was solved simply by creating two parks around the Palace of Justice, which together were called Schmerlingplatz (the eastern one is now called Grete-Rehor-Park, a tiny traffic island is called Leopold-Gratz-Platz ). The city expansion fund donated the space to the City of Vienna. City gardener Gustav Sennholz laid out the park in 1885, the cost was 28,750 guilders (approx. 250,000 euros).

Friedrich-Schmidt-Platz: 1884, one year after the completion of the town hall, garden architect Lothar Abel planned a park in the west of the town hall. The planned costs of 69,179 guilders were not acceptable to the municipal council. The building authority reduced Abel's draft to 32,483 guilders. Finally, the park was created in 1885 for only 26,800 guilders (approx. 240,000 euros).

Rudolfsplatz: In 1872 the city expansion fund gave the municipality of Vienna a plot of land on what would later be Rudolfsplatz in order to build a market hall here. As at Börseplatz, the city lost its interest in a market here too. In 1887 the square was converted into a park according to plans by Gustav Sennholz for 4,134 guilders (approx. 36,000 euros).

Maria-Theresien-Platz: The area between the two museums was not created by the municipality of Vienna, but by the court at the expense of the state budget. The park was designed as a French garden and without trees. The City of Vienna relocated and financed the water supply for the park on the condition that it must always be accessible to the public. When the Maria Theresa monument was inaugurated on May 13, 1888, the green space was already completed.

Park at the Elisabeth monument: The Volksgarten was expanded to erect the monument to the murdered Empress Elisabeth . According to plans by architect Friedrich Ohmann , the court garden administrator Josef Vesely laid out a 45 meter wide garden in 1905, which is axially aligned with the monument to the empress.

After the ring road zone was largely completed, the remaining open spaces were designed as - mostly nameless - green areas, which were then called "jewelry systems". These are u. a. the green areas at Deutschmeisterplatz (1891), around the Secession (1898), at Karlsplatz and Schwarzenbergplatz (from 1900), at the Hochstrahlbrunnen (1903), at Morzinplatz (1904), the junction of the Wollzeile (today's Dr.-Karl-Lueger- Platz , 1904), the gardens at the Goethe monument (1906) and the (today's) Georg-Coch-Platz (1907).

Conclusion

With the beginning of World War I in 1914, the expansion of the city was essentially complete. Although there was no central planning, the project was and is generally rated as very successful. The Ministry of the Interior, especially Franz von Matzinger, had the greatest influence on the planning. His city expansion fund financed the project and therefore always had the opportunity to participate in the planning. There were no timeouts because there was never a schedule.

The city expansion fund financed the Neue Burg, the expansion of the Hofburg towards Michaelerplatz, the opera, the Burgtheater, as well as the art and natural history museums. The university and several university outbuildings, several commercial and secondary schools, the Academy of Fine Arts, the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry, the Parliament building, the Palace of Justice, the Rossau barracks and several post and telegraph buildings were built at the expense of the state budget. The city of Vienna paid for the town hall, several elementary and community schools and some market halls. The Votive Church, the stock exchange, several theaters, many bank buildings and hotels, and of course the numerous apartment buildings were financed privately.

With the demolition of the city walls - which hinder the wind - and the creation of numerous green areas in the ring road zone, the city's microclimate improved noticeably. The dust clouds on the glacis were a thing of the past, and the generally better air quality reduced tuberculosis . While the death rate in Vienna was 49 deaths per 1,000 inhabitants in 1855, it had fallen to 24 deaths in 1891 (2013: 11 deaths).

Appendix: The handwriting of Emperor Franz Josef I from December 20, 1857

Se. kk Apostolic Majesty have deigned to issue the following very high hand letter to the Minister of the Interior regarding the expansion of the inner city of Vienna:

- (Note: The original of this imperial handwriting was destroyed on July 15, 1927 in the Palace of Justice fire.)

“Dear Baron von Bach! It is my will that the expansion of the inner city of Vienna should be tackled as soon as possible with consideration for a corresponding connection between it and the suburbs, and that consideration should also be given to the regulation and beautification of my royal and royal capital. At this end I authorize the abandonment of the walls and fortifications of the inner city, as well as the trenches around it. "

- (Note: The "abandonment of the walling and fortifications", ie the razing of the city fortifications, was an initiative of Interior Minister Alexander von Bach. He came up with the present handwriting and had it formulated by Franz von Matzinger.)

That part of the area and glacis grounds obtained through the abandonment of the walling around the fortifications and moats, which is not reserved for any other purpose in accordance with the basic plan to be drawn up, is to be used as building ground and the proceeds gained from this must be used to form a building fund, from which the expenses accruing to the state treasury as a result of this measure, in particular also the costs of the construction of public buildings, as well as the relocation of the still necessary military institutions are to be paid for.

- (Note: The establishment of the city expansion fund is ordered here; the public buildings on the Ringstrasse are to be financed through the sale of building land.)

When drafting the relevant basic plan and, after my approval, when carrying out the city expansion, the following points of view must be assumed:

With the clearing of the walls and fortifications and the filling of the city ditches in the route from the beaver bastion to the surrounding wall of the Volksgarten, a wide quay is created along the Danube Canal and the space gained from the Schottenthore to the Volksgarten is partially used Regulation of the parade ground can be used.

- (Note: The Franz-Josefs-Kai is located here. The square "from the Schottenthore to the Volksgarten" is the military parade ground.)

Between these given points, the inner city has to be expanded in the direction towards Rossau and Alservorstadt, following the Danube Canal on the one hand, and the borderline of the parade ground on the other, but with due consideration for the corresponding enclosure of the votive church currently under construction.

- (Note: In previous years, numerous projects for city expansion proposed building up the area around today's Schottenring; this is now being ordered.)

In the construction of this new part of the city, consideration must first be given to the construction of a fortified barracks, in which the large military bakery and the staff house are to be accommodated, and these barracks have been removed eighty (80) Viennese fathoms from the Augarten Bridge downwards to come to lie in the extended axis of the main surrounding road leading there.

- (Note: The war ministry was only informed shortly before the publication of the "handwriting". In the rush, the military could think of no better demand than that the - already planned - Rossau barracks should be built and a "military bakery" should be located in it. and a "staff house" must be located.)

The square in front of Meiner Burg, along with the gardens on both sides of it, must remain in its current state until further notice.

- (Note: At that time, Bach and Matzinger did not yet have a concrete plan of how the area around the later Heldenplatz should be built, and therefore left the questions unanswered.)

The area outside the Burgthores up to the imperial stables must be left free. Likewise, the part of the main wall (beaver bastion) on which the barracks bearing My Name is located must continue to exist.

- (Note: The "area outside the Burgthores" is today's Maria-Theresien-Platz, which was actually not built. In the second sentence, the military is afraid that the Franz-Josefs-Kaserne could be torn down; the fear was well founded Barracks were demolished in 1900.)

The further expansion of the inner city is to be carried out at the Kärnthnerthore, on both sides of it in the direction towards the Elisabeth and Mondschein Bridge as far as the Karolinenthor.

- (Note: Bach and Matzinger wanted to start construction in the area where the later opera was, which is what happened.)

The construction of public buildings, namely a new general command, a city command, an opera house, an imperial archive, a library, a town hall, and then the necessary buildings for museums and galleries must be taken into account and the places to be determined for this are to be taken into account to specify the exact extent of the area.

- (Note: The "Stadthaus" should serve the city of Vienna for representation and events. It was an idea of Trade Minister Toggenburg and was never built. The stock exchange was built in its place. Alexander von Bach wanted to build a central Reich archive Neither was it built, nor were the General Command, City Command, library and the “galleries.” Of the buildings mentioned in the imperial letter, only the opera and the museums were built.)

The space from the Karolinenthore to the Danube Canal should also remain free, as should the large parade ground of the garrison from the place in front of the Burgthore up to the vicinity of the Schottenthor, and the latter has to be connected directly to the place in front of the Burgthore.

- (Note: The Karolinentor was located on Johannesgasse; from there to the Danube Canal no construction should take place. From Johannesgasse to today's Weiskirchnerstrasse, the city park was laid out. From the park to the Danube Canal, the military wanted a clear field of fire for the Franz-Josefs- The Stubenring was laid out here from 1901. The "large parade ground of the garrison" is the parade ground between what is now the Universitätsring and the ladenstrasse. It was supposed to remain with the military and was not allowed to be built up; in the end, parliament, town hall and university were built here. )

From the fortified barracks on the Danube Canal to the large parade ground, a room one hundred (100) Vienna fathoms wide has to be left free and undeveloped. Otherwise, however, a belt at least forty (40) fathoms wide, consisting of a driveway with footpaths and bridle paths on both sides, should be laid out on the Glacisgrunde in the connection to the quai along the Danube Canal around the inner city that this belt should be appropriately bordered by buildings alternating with free spaces designated for gardens.

- (Note: In the first sentence the military wants a free field of fire from the Rossauer barracks along today's Kolingasse to the Schottentor; the area was built up. In the following sentence, the construction of the Ringstrasse is arranged; the required width of 40 fathoms [75 , 9 meters] was later reduced to 30 fathoms [56.9 meters].)

The other main streets are to be laid out in the appropriate width and even the secondary streets not less than eight fathoms wide.

- (Note: 8 fathoms are 15.2 meters.)

No less attention is to be paid to the erection of market halls and their corresponding distribution.

- (There were numerous markets around the ring road zone: Mehlmarkt, Heumarkt, Tandelmarkt, fruit market and grain market. Market halls were not built on the Ringstraße.)

At the same time, the regulation of the inner city must be kept in mind when drafting the basic plan for urban expansion and therefore the opening of corresponding new exits from the inner city, taking into account the main traffic lines leading into the suburbs, as well as the creation of new ones mediating those traffic lines Appropriate attention should be paid to bridges.

- (Note: The suburbs are to be better connected to the city center through appropriate traffic routes, and the construction of further bridges over the Danube Canal is being considered.)

In order to obtain a basic plan, a bankruptcy is to be advertised and a program based on the principles outlined here must be published, but with the addition that the competitors are left free leeway in drafting the plan, as well as other suitable proposals in this regard should not be excluded.

- (Note: the implementation of an architectural competition is arranged here.)

A commission made up of representatives of the Ministries of the Interior, of Commerce, also of My Military Central Chancellery and the Supreme Police Authority, a member of the Lower Austrian Lieutenancy and the Mayor of the City of Vienna, is then suitable for assessing the basic plans received to be formed by the Ministry of the Interior in agreement with the other central offices mentioned here under the chairmanship of a section chief of the Ministry of the Interior to be appointed experts and are three basic plans recognized by this commission as the best with prices, namely in the amounts of two thousand to distribute one thousand and five hundred imperial coin ducats in gold.

- (Note: This is where the basic composition of the jury and the cash prizes to be awarded are arranged.)

The three basic plans recognized hereafter as the most excellent are to be submitted to me for the final version, just as my resolution will have to be obtained on the further modalities of the execution with reimbursement of the related requests.

Because of the execution of these My orders, you immediately have to dispose of the appropriate measures.

Vienna, December 20, 1857

Franz Joseph mp

- (Note: the city expansion was announced on December 25th, Christmas Day. Whether this was a calculation or a coincidence cannot be inferred from the sources.)

literature

- Elisabeth Springer: History and cultural life of the Vienna Ringstrasse. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1979. ISBN 3-515-02480-8 . Volume II by Renate Wagner-Rieger (Ed.): The Vienna Ringstrasse. Picture of an Era (Volumes I – XI). Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1972–1981. ISBN 978-3-515-02482-2 .

- Kurt Mollik, Hermann Reining, Rudolf Wurzer: Planning and implementation of the Vienna Ringstrasse zone . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1980. ISBN 3-515-02481-6 . Volume III by Renate Wagner-Rieger (Ed.): The Vienna Ringstrasse. Picture of an Era (Volume I – XI). Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1972–1981. ISBN 978-3-515-02482-2 .

Web links

- suf.at - Vienna Ringstrasse

- The Ringstrasse - a jewel among the streets of the world

- interactive website about the Vienna Ringstrasse at ringview.vienna.info

Individual evidence

- ^ [1] Wiener Zeitung, January 31, 1858. Retrieved on April 26, 2015 from ÖNB / ANNO AustriaN Newspaper Online

- ^ Exhibition catalog The Unbuilt Vienna - Projects for the Metropolis. Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, 1999, p. 94 ff.

- ↑ Quaipark at www.zeno.org/Literatur, accessed on March 23, 2015

- ^ Felix Czeike : Historical Lexicon Vienna. Volume 1: A – Da. Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-218-00543-4 .

Coordinates: 48 ° 12 ′ 16.7 " N , 16 ° 21 ′ 45.7" E