Vienna light rail

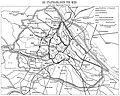

The Wiener Stadtbahn , also known as the Wiener Stadt- undverbindungsbahn, was a public transport system opened in 1898 in the Austrian capital Vienna and its surroundings. Originally the Stadtschnellbahn was a standard-gauge railway operated by the Imperial and Royal State Railways with steam locomotives and classified as a full -gauge railway , which, in addition to passenger traffic, also served to transport mail , luggage and goods . Your 37.918 km long narrower network consisted of six individual sections, namely the Upper Wientallinie, the Lower Wientallinie, the Danube Canal line, the belt line, the connection bend and the suburban line . In 1925, the communally operated Wiener Elektro Stadtbahn took over a large part of this network, which in turn was incorporated into the Vienna U-Bahn between 1976 and 1989 . Only the suburban line remained with the state railway, it has been part of the Vienna S-Bahn since 1987 .

The closer network is thus now fully electrified and is served by Wiener Linien (WL) with the U4 and U6 lines and the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB) with the S45. Only a short section of the belt line, most of the connecting arch and the Unter-Döbling intermediate station are closed today.

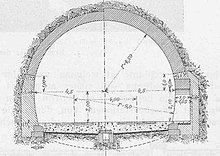

Even in the densely built-up urban area, the light rail system was consistently free of crossings from the start , i.e. without level crossings , and was therefore very laboriously laid out. It received numerous elevated sections on bridges , viaducts and the characteristic brick-walled city railway arches, as well as further subsections in low-lying areas in incisions , in galleries or as a paved railway directly under the road surface.

It is one of the main works of the architect Otto Wagner , who not only designed the substructure and all building structures such as retaining walls , lining walls , bridges, viaducts, tunnel portals and stations , but also all associated ticket and baggage counters , floor coverings, railings , elevators , grids, Gates, furniture, water pipes as well as heating and lighting fixtures. The infrastructure was largely preserved and, as a total work of art in the transition style between late historicism and early art nouveau, is one of the city's sights . All of the facilities are now listed .

history

prehistory

Starting position

In the middle of the 19th century, a railway line led to Vienna from every direction. These were the Northern Railway opened in 1837 , the Southern Railway opened in 1841 and the Eastern Railway opened in the same year and the Western Railway opened in 1858 . In 1870, 1872 and 1881 the Franz-Josefs-Bahn , the Nordwestbahn and the Aspangbahn were added. Each of the seven routes belonged to a different railway company and each had its own train station in the capital, some of which were built far outside the city center in an area that was still undeveloped at the time for spatial, fiscal and military reasons. Six of them were also designed as - difficult to expand - terminal stations , only the last opened Aspang station was a through station from the start . While the comparatively few passengers who did not have the capital as their starting or destination were able to switch between the stations with the Vienna tram , which was set up in 1865 , this turned out to be far more difficult for transit goods traffic .

In addition, at the end of the 19th century it became apparent that the terminal stations themselves - including above all the Westbahnhof and Franz-Josefs-Bahnhof - urgently needed relief. In the long run, they no longer met the complicated demands of parallel long-distance and local traffic and would have had to be costly rebuilt without the construction of the light rail.

While the competing railway companies had no interest in a central urban solution at the time - today's Vienna Central Station ultimately only went into operation in 2012 - the Austrian military demanded measures after the March Revolution of 1848 to prevent such events from happening again. Although the connecting line Meidling – Nordbahnhof from 1859, the connecting line Penzing – Meidling from 1860, the Donauländebahn from 1872 and the Danube shore line from 1875 provided a certain remedy, not least the loss-making battle of Königgrätz in 1866 showed that further cross-connections between the Long-distance railways were missing. After only 18 kilometers of the Austrian railway network - including the connecting railway - were in state hands in 1867, another wave of nationalization began in 1874. The standardization of operations associated with the de-privatization as well as the new links in the capital should make it easier to move troops, weapons and ammunition in the event of mobilization - especially in the case of a two-front war . But the so-called approval traffic - that is, supplying the city and soldiers with food - also played a major role in the future of Vienna's light rail system. Equally important was the possibility of connecting the large inner-city barracks to the main railways in the event of war , including in particular the arsenal built between 1849 and 1856, also as a result of the March Revolution .

Another important aspect in the construction of the light rail was the razing of the line wall , a fortification around the suburbs of Vienna. It had become militarily obsolete in the middle of the 19th century, which initially led to the construction of the 75 to 80 meter wide belt road from 1873 , with the inner belt running inside the wall and the outer belt outside the wall. The demolition of the fortifications, which began in 1894, then made way for new urban railway lines. Therefore, an early alternative name for the light rail is belt rail or short belt path .

It also became clear early on that, for reasons of synergy, it would make sense to link the light rail construction with two other major urban projects in the second half of the 19th century. On the one hand, this was the regulation of the Vienna river, including partial bulging, and on the other hand, the further expansion of the Danube Canal . Both measures primarily served the purpose of flood protection , with a commercial and winter port also being built on the Danube Canal in Freudenau , which is also flood-proof. In addition, the Danube Canal in the course of progressive was parallel to the city railway construction Wiener channeling two collection channels, the left main collection channel and the right-hand main collecting duct . The area gained by straightening the two rivers could thus be used for the tram routes, the expensive purchase of private land and the demolition of existing buildings was not necessary.

Early projects on the occasion of the first city expansion in 1850

In Vienna, relevant projects for railway lines in the urban area existed very early on. The oldest dates back to 1844, when the engineer Heinrich von Sichrowsky designed an atmospheric railway based on the system of George Medhurst and Samuel Clegg based on the London and Paris model . This should lead from Lobkowitzplatz below the Wiener Glacis on to the Wien River and to Hütteldorf. In 1849, Julius Pollack finally proposed that the Vienna connecting railway, which was still in the planning stage at the time, also be operated atmospherically.

The next plans followed in connection with the first city expansion in 1850, including a project preferred by the Wiener Baugesellschaft and the Wiener Bankverein in 1852 . Count Henckel von Donnersmarck presented the second proposal, which had already been worked out in detail, in 1867. In 1869, building councilor Baron Carl von Schwarz finally brought in a third "urban railway design". A name was thus fixed for the project, which soon became common parlance. In addition, the term “Stadtbahn” was also common in Berlin by 1872 at the latest. Outside the two capitals, however, “Stadtbahn” established itself at the end of the 19th century as an alternative term for a classic electric tram . In Vienna, as in Berlin, people spoke of a city railway in the 19th century . Another term popular in Vienna at the time was the metropolitan (iron) railway , derived from the Metropolitan Railway , which opened in London in 1863 and was the world's first underground railway .

Aside from the financial resources, the complex communication and ownership relationships involved in urban railway construction also presented all those involved with major challenges, which is why the project did not progress for years. As early as Carl Ritter von Ghega , who built both the complicated Semmering Railway and the Vienna connecting railway parallel to one another in the 1850s, the saying has been passed down:

“I would rather build two Semmering trams than this light rail. [Meant is the connecting line.] "

Competition of the Ministry of Commerce on the occasion of the world exhibition (1873)

As a result of the economic upswing from 1871, the light rail came back on the agenda. As a result of a competition launched by the Ministry of Commerce, 23 new plans were received by March 1, 1873, when Vienna wanted to position itself as a modern city on the occasion of the World Exhibition that opened on May 1, 1873 . This included, for the first time, a proposal for a pure tunnel runway, presented by Emil Winkler . Its planning was also based on the first systematic traffic census in Vienna. Even then, the ministry expressed the principle that level crossings with existing roads could not be permitted, so that only elevated, underground or gallery railways came into question.

As a result of the economic crisis that occurred in May 1873 as a result of the Vienna stock market crash , interest in the so-called light rail issue subsided somewhat. None of the 23 drafts received a concession , even though the municipality judged that of Count Edmund Zichy's consortium to be the most appropriate to public interests, both in terms of the local railway network applied for and the proposed regulation of the Vienna River. The project by Zichy and his colleagues Baron Rothschild, Baron von Schey, Baron Carl von Schwarz, Achilles Melingo, Otto Wagner and Georg Scheyer envisaged an exclusively elevated railway with a central station between Aspernbrücke and Augartenbrücke . From there the light rail should lead on the one hand to Baumgarten on the Westbahn, on the other hand along the Danube Canal to the Franz-Josefs-Bahnhof and along the existing line ramparts to Rennweg . Further routes were planned to the Reichsbrücke , to Hernals , to the Südbahnhof, to Brigittenau or to Floridsdorf .

Model Berlin (1882)

After almost ten years without any progress, the German capital Berlin finally gave the immediate impetus for a renewed discussion of the Viennese light rail issue. The Berlin Stadtbahn operated there as early as February 7, 1882 , and later served as a model for the Viennese Stadtbahn in several ways. Although it was routed exclusively in an elevated position on viaduct arches , it was also operated by the responsible state railway with steam locomotives and a short train sequence and connected several previously existing terminal stations with one another. In contrast to what happened later with the Vienna Steam Light Railroad, Berlin already had a rigid schedule .

In this context, three new drafts were submitted to the Austrian government, the first even in the year before the opening of the Berlin facility. This was presented in August 1881 by a consortium of British engineers James Clarke Bunten and Joseph Fogerty, which - as the thirtieth light rail project in total - led for the first time to the concession stage on January 25, 1883. A main station on the Danube Canal and a double-track belt railway with branches to all Vienna train stations and to Hietzing were planned . The construction of the approximately 13 kilometer long ring was planned along the Danube Canal and Vienna River as an elevated railway on iron viaducts, on the belt partly as a viaduct, partly as an open or covered incision. The branch lines should all be built as elevated railways, mostly on viaducts. However, the concession of the two British was declared expired on March 14, 1886 by the Austrian government because financial evidence of the estimated costs of 719 million Austrian crowns could not be provided.

In competition with Bunten and Fogerty was the project presented by the municipal building authority in 1883 for the installation of a light rail system in Vienna , which the municipality of Vienna preferred. It should be composed of the following three main lines:

- a double-track belt line from the Südbahnhof to the connection to the Nordbahn and the Nordwestbahn, mostly intended as an elevated railway

- a central four-track underground railway, as the diameter line should open in a north-south direction, the Inner City

- a Wientalline to be built as an elevated railway from the Westbahnhof to the former Schickaneder Bridge at today's Getreidemarkt

In addition, in 1884 Siemens & Halske submitted the project for a network of electric light rail vehicles for Vienna . The latter, however, was narrow gauge and was therefore not accepted because the responsible authorities feared that this could prevent the creation of further light rail vehicles with steam operation.

Planning and construction

Another attempt on the occasion of the second major city expansion in 1892

The light rail project became concrete for the first time in 1890, when the former Krauss & Comp. The drafts submitted were approved as a basis for the official negotiations, although these suffered numerous changes in the course of the following years. One of the reasons for the renewed attempt to build the tram was the continuing economic upswing in Austria. In 1889 and 1890 - after a long deficit period - this led to a balanced state budget again, and in 1891 a surplus was even achieved. On the other hand, the Lower Austrian Landtag decided that Vienna was still part of the Province of Lower Austria , and in December 1890 the capital was to be united with its suburbs to form Greater Vienna .

During this second major city expansion, the existing districts 1 to 10 were added to the new districts 11 to 19, which lost their independence with effect from January 1, 1892. As a result, the urban area increased from 55 to 179 square kilometers, the population rose from 800,000 to 1,300,000. As the city grew, the light rail project became even more urgent. At the same time, the western expansion of the city required the extension of the light rail project to include the suburban line.

Finally found later in kk Ministry of Railways , from October 5 to November 16, 1891 one, which was the Commerce Department until 1896 still part of inquiry instead. It turned out that the decision to build would only have to be made jointly by the state, state and municipality. Therefore, the Ministry proposed the creation of an equal occupied Commission before.

In agreement with the Province of Lower Austria and the City of Vienna, the government of Prime Minister Eduard Taaffe therefore submitted to the Reichsrat on February 6, 1892 an extensive bill on the implementation of the transport facilities in Vienna , which also laid down the urban railway lines. Both houses of the Reichsrat accepted this and promulgated it as a law of July 18, 1892. The credit for this goes primarily to Dr. Heinrich Ritter von Wittek , 1897–1905 kk railway minister.

The Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna , proposed by the Ministry , was finally constituted on July 25, 1892 and acted as the building contractor for the construction of the city railway, the Vienna river regulation and the Danube Canal expansion. On October 27, 1892 the ministerial decision was made, whereby the alignment of all lines received approval. On December 18, 1892, the commission finally received the official concession for the operation of the light rail. The construction work itself, however, was transferred to the state railway. This was done for the main lines by agreement of May 27, 1893 and for the local railway lines by means of a supplementary agreement of September 27, 1894.

Proposal by Anton Waldvogel , 1892

Differentiation between main and local railways

The light rail network planned in 1892 was divided into two main groups. These included main railways, which would allow the transfer of the running equipment of the railways flowing into Vienna and which were to have connections to them, as well as local railways that were much cheaper to build. The latter were to be routed as branch lines and operated by private railways . For the local railways, the option of transferring the main railroad's operating equipment was only limited and a connection to the other railways was not planned at all. The total cost was then estimated at 73 million Austrian guilders . In detail, the two route categories differ as follows:

| Fee distribution: | Minimum radius on free route: |

Minimum radius in the station area: |

Maximum gradient: |

Track spacing on straight sections: |

Clearance profile over top of rail : |

|

| Main lines: |

State : 87.5 percent, city: 7.5 percent, country: 5 percent |

160 meters | 150 meters | 20 per mille | 4.00 meters | 4.8 meters |

| Local railways: | State: 85 percent, city: 10 percent, country: 5 percent |

150 meters | 120 meters | 25 per mille | 3.80 meters | 4.4 meters |

The latter distinguishing feature would, however, have ruled out a transfer of trains from the main lines to the local lines. But those in charge later decided to also build the local railways with a clearance height of 4.8 meters. Thus, the clearance profile of the light rail was ultimately not subject to any restrictions in comparison to the other main lines in the country. The maximum gradient of 25 per mille corresponded to that on the Semmering Railway. In the first construction phase - to be completed by the end of 1897 - six routes with a total length of 47.4 kilometers were originally planned:

- As main lines:

- The 15.3 kilometer long and 25,415,000 Austrian guilders expensive belt line , also known as the belt line , from Heiligenstadt to the southern line in Matzleinsdorf , plus a branch line running parallel to the western line between the western station and Penzing

- The 5.6 kilometer long and 3,600,000 Austrian guilders expensive Danube city line from Praterstern to the Donauuferbahn and on to Nussdorf, whereby an elevated railway was planned between Praterstern and the marshalling yard of the northern railway on Vorgartenstraße, but initially only a provisional level railway was planned at street level

- The 9.3 kilometer long and 9,700,000 Austrian guilders expensive suburban line from Penzing via Ottakring and Hernals to Heiligenstadt

- As local railways:

- The 7.2 kilometer long and 9,360,000 Austrian guilders expensive Wientallinie or Wientalbahn , at that time still written Wienthallinie or Wienthalbahn , from the Westbahnhof over the Gürtel to the Gumpendorfer slaughterhouse and from there along the Wien River to the main customs office, along with a branch from Gumpendorf to the steam tramway from the Schönbrunn line to Mödling

- The 6.0 kilometer long and 7,900,000 Austrian guilders expensive Danube Canal Line , at that time still written Danube Canal Line , from the main customs office to Heiligenstadt - in the early days of the Stadtbahn after the Franz-Josefs-Kai sometimes also called Quailinie or Quaiinie , with only one alternative here 3.8 kilometers long and only 5,700,000 Austrian guilders expensive variant from the main customs office to Franz-Josefs-Bahnhof was under discussion

- The 4.0 kilometer long inner ring line , which costs 5,400,000 Austrian guilders , branches off the Wientallinie at Karlsplatz and runs along Museumsstrasse, Landesgerichtsstrasse, Universitätsstrasse and Schottenring to the connection to the Danube Canal line at the Kaiserbad

When the traffic demand arose, the following supplementary routes were planned in a second construction phase from 1898 to 1900:

- As main lines:

- A stretch along the Danube Canal to link the Franz-Josefs-Bahn with the connecting railway

- The execution of the Donaustadtlinie in a definitive way, that means also to the north of the marshalling yard of the Nordbahn on the Vorgartenstraße as an elevated railway, this should extend over the entire length of the Danube city

- As local railways:

- A cemetery line, branching off the Wientallinie, to the central cemetery and on to Schwechat using the private railway Vienna-Aspang (EWA)

- Branches from the inner ring line to the belt and suburb line with continuations towards Dornbach and Pötzleinsdorf

- two radial tracks through the inner city, for which electrical operation was planned from the start

In connection with the connection to the central cemetery, it was even planned to transport corpses by light rail towards the end of the 19th century ; the permit for this was expressly stated in the concession conditions. However, this request was later turned down because the then very numerous private funeral homes vehemently objected to it. Alternatively, from 1918 onwards, the tram was used to transport coffins for several years.

Start of construction (1892)

Ultimately, the suburban line, which in places has the character of a mountain railway, was the most difficult section and was therefore postponed until December 1893. As a result, the light rail construction began on February 16, 1893 with the belt line in Michelbeuern station . Before that, however, the groundbreaking ceremony on November 7th, 1892 began with the removal of the water reservoir of the former Kaiser-Ferdinand aqueduct in front of the Western Railway. So this day can already be seen as the start of construction. On August 1, 1892, kk Oberbaurat Albert Gatnar was appointed site manager for the suburb line, while kk Oberbaurat Anton Millemoth was responsible for the belt line and kk Oberbaurat Professor Arthur Oelwein was responsible for the Vienna line and the Danube Canal line.

At the end of 1894, the Hütteldorf-Hacking-Hietzing section of the Upper Wiental Line was already under construction, and the Lower Wiental Line finally followed in 1896. The last to begin with was the construction of the Danube Canal Line on January 13, 1898, although no separate date has been handed down for the connecting arch that was built together with it.

In advance, the commission had to acquire numerous plots of land ranging in size from a minimum of eight square meters to a maximum of 35,700 square meters. The compensation ranged between two and a half and 153 Austrian guilders per square meter, depending on the location. In 436 cases, an amicable settlement was achieved with the previous owners, only in 22 other cases had to be expropriated by court decision . However, the value of the houses and land along the railway increased significantly as a result of their construction, that is, the light rail - which caused this increase in value - had to pay the higher prices itself when redeemed. Individual buildings also had to give way to the tram. Among them, for example, one of the line chapels on the Gürtel in 1893 , the so-called bridge chapel . As a substitute, Otto Wagner built the St. Johannes Nepomuk Chapel in the immediate vicinity of the old location from 1895 ; it was consecrated in 1897. In general, the light rail system had a considerable influence on the streets and squares in its vicinity as well as the economic conditions of the affected districts. For example, the existing Gürtelstraße was freed from the many protruding old buildings and the tram arches were erected on its mirrored grounds, where building materials, stones, scrap iron and the like were previously stored behind wooden crates and dilapidated fences. The remaining part of the belt mirror was then converted into gardens.

The new inner-city transport network of the capital was regarded as a state prestige object of Cisleithania, which is why the state guaranteed all the necessary funds and thus made it possible to implement it quickly. In addition, cheap labor from all over the monarchy was available; At times, up to 100,000 people were working at the same time. These included mainly Czechs, Slovaks, Italians, Slovenes, Lower Austrians and Styrians, and to a lesser extent also workers from other parts of Austria-Hungary and even from abroad, including France, Greece and Italy. Furthermore, women were already working as mortar mixers in the construction of the light rail. In the years 1893 to 1896, the weekly and daily wages of workers and craftsmen increased significantly. The reason for this increase was that other very extensive structures were being carried out in Vienna at the same time as the construction of the urban railway. The workforce required for this could only gradually be brought in in the required number.

Separate material runways were created for the construction of the light rail . Including one from the companies Peregrini, Calderai and Giuseppe Feltrinelle & Co. from Schikanedersteg to the Danube Canal for the construction of the Wientallinie and a second from the company Rabas & F. Rummel from Penzing to Breitensee, where the Linzer Straße was even crossed on a wooden viaduct .

The state railway also takes over the local railways, the inner ring line is no longer available (1894)

The steam tramway company formerly Krauss & Comp originally applied for the concession of the three lines of the first construction phase to be operated as local railways . She hoped for a link with the routes she already operated to Mödling in the south and Stammersdorf in the north, but could not prove the necessary funds. As early as January 16, 1894, all three boards of the Commission for Transport Systems decided unanimously to run the local railway lines themselves. This was approved by law of April 9, 1894, and by the ultimate decision of August 3, 1894 , the State Railways finally also received the concession for the Wiental line and the Danube Canal line.

The two routes then had to be rescheduled to enable the trains to transfer from the main lines to the local lines. In return, the steam tramway company suffered a disadvantage due to the rescheduling. Because in order to clear the construction site for the Stadtbahn, it had to shut down its 3.221 kilometer stretch of Hietzing – Schönbrunn line on December 31, 1894 - which was only opened on December 22, 1886 - and also to build a new terminus in Hietzing. Furthermore, in 1894 the Hütteldorf-Hacking-Hietzing section, which was not originally planned for the first construction phase, was brought forward in order to link the Wiental line with the Western Railway. As a result, the Westbahnhof – Penzing side branch of the belt line was obsolete and disappeared from the planning. As an alternative, a connecting curve between the stations Gumpendorfer Straße and Meidling-Hauptstraße was newly included in the planning. Despite the missing track triangle at the Westbahnhof, it should enable direct train journeys between the belt line and the Westbahn.

The third local line of the first construction phase, the inner ring line , was completely discarded in 1894. Although it should continue to be reserved for a private railway, the concession should only be granted when the line can be run electrically. Ultimately, this connection, with a partially similar route, was not created until 1966, initially as a sub-paving tram in the course of the so-called two -way line , which finally mutated into underground line 2 in 1980 .

Constraints on financial savings in the project (1895–1897)

The rescheduling of the Vienna and Danube Canal lines made the project more complicated and expensive. Due to the architectural quality required by Otto Wagner, the high-rise buildings on the more important routes were also much more expensive than planned before 1894. The second construction phase was a long way off. In addition, on July 11, 1895, the commission decided to postpone the Donaustadt line , which was still assigned to the first construction phase , for which 264,915 Austrian crowns had already been incurred for preliminary work, projection costs and land acquisition. The four intermediate stations planned on this route - Kronprinz-Rudolfs-Brücke , Gaswerk , Lederfabrik and Donau-Kaltbad - were thus obsolete.

The plans were further specified by the law of May 23, 1896. In addition, in August 1896, a kk building department for the Vienna Stadtbahn was established as a separate department in the railway ministry and Friedrich Bischoff Edler von Klammstein was appointed as kk section head or building director, replacing it the then dissolved General Directorate of the Imperial and Royal State Railways . Von Klammstein was responsible for the three construction managers for the suburb line, the belt line and the Vienna line. Furthermore, the belt line was divided into nine, the suburban line and the Wiental line each into five and the Danube Canal line into three construction sections , these construction sections in turn into smaller working sections.

The various construction managers employed around 70 civil servants, including 50 technicians. The kk Bauräthe Tlach, Hugo Koestler, Christian Lang, Josef Zuffer and Alexander Linnemann acted as speakers for the substructure, superstructure, building construction and materials management of this building department. The kk Hofrath Dr. Victor Edler von Pflügl. The administrative business of the Commission for Transportation Systems was initially headed by the Lieutenancy Council Baron von Hock, later the Lieutenancy Council Lobmeyr. Ministerialrat Doppler acted as technical advisor .

Also in 1896 the project operators reduced the plans for the construction of the belt line. It was actually supposed to lead from the Gumpendorfer Straße station - the wall approaches built as preliminary construction work are still visible there today - via the unrealized Arbeitergasse station in the Gaudenzdorfer Gürtel / Margaretengürtel area to the Matzleinsdorf freight station of the southern railway. From there, a continuation over the Laaer Berg to the Ostbahn was considered. The problem was the not yet nationalized Südbahn-Gesellschaft , whose infrastructure was to be used by the light rail trains in the so-called péage traffic . That is why it was determined at the time:

"The construction of the Gumpendorferstrasse – Matzleinsdorf belt line is only to be carried out when the relationship between the Southern Railway and the State Railways has been finally settled."

The saved connection between Gumpendorfer Strasse and Matzleinsdorf, however, threatened to have a negative impact on future operations because the belt line from the main customs office would not have been accessible without changing the direction of travel . In order to compensate for this shortcoming, those responsible therefore integrated the connecting sheet into the planning at short notice in 1896. Another saving measure concerned the arches of the viaduct. The plaster facade originally planned by Otto Wagner was dropped in favor of the exposed bricks , as was previously the case with the connecting railway and the Berlin urban railway.

Apart from the completely saved sections of the route, by a resolution of the municipal council in 1897, the intermediate stations “ Spittelau ” on the belt line and “Rampengasse” on the Danube Canal line were also canceled without replacement. In the end, both went into operation as the Spittelau traffic station in 1996 , in a heavily modified form and a little further south than originally planned.

Construction problems in the Wiental and at the main customs office (1897)

While the construction of the suburban line, the Upper Wiental Line and the Belt Line only caused minor difficulties, the Lower Wiental Line caused significantly greater problems due to complications in connection with the regulation and partial bulging of the Vienna River. The course of the river often had to be completely relocated in order to create space for both objects. In some places whole groups of houses were demolished. The construction was most difficult at those points where the foundations of the light rail walls often reached six to seven meters below the foundations of the old neighboring houses. In addition, the flood events that occurred at the time caused extensive damage to the buildings that were in the critical stage of their foundations and led to construction interruptions. This was particularly true of the so-called flood of the century in July 1897.

The second major difficulty in building the Wientallinie was the complex lowering of the Hauptzollamt station, which was originally in an elevated position and had to be lowered by 6.82 meters for the tram because both adjacent new lines were underground. This project was made even more difficult by the existing connection to the Praterstern, which in turn remained an elevated railway.

Postponement of the opening date

Originally, all lines of the first construction phase were to go into operation together at the end of 1897. Due to the varying degrees of delays, the client finally decided not to open the entire network at the same time. As an alternative, the following completion plan applied at the beginning of 1898:

- Suburban line until the end of April 1898

- Upper Viennese line and belt line until June 1, 1898

- Lower Wientallinie and connecting line until June 1, 1899

- Danube Canal Line until the end of 1899

Ultimately, however, the postponed opening date could only be met for the Upper Wiental Line and the Belt Line, while the other sections were delayed even further.

Short-term rescheduling of the Danube Canal line and the connecting arch (1898)

Due to resident protests in the IX. In the course of 1898, and thus in a very late phase of the project, the Schottenring – Brigittabrücke section, originally intended as an elevated railway, had to be rescheduled into a more expensive underground line. The associated additional costs of 4.6 million Austrian crowns, however, were taken over by the municipality of Vienna by resolution of the municipal council on June 1, 1898. This measure made the opening of the Danube Canal line obsolete before the turn of the century, because the section in question could only be tackled in autumn 1898 while the rest of the Danube Canal line had been under construction since the beginning of the year.

The lowering of the route was also structurally challenging. The reasons for this were the foundations of the city-side retaining walls at Morzinplatz and the translation of the Alserbach . At Morzinplatz, the workers first encountered the old fortification walls on the surface, underneath the floating sand there made the construction work more difficult. The right main collecting canal, which had been built recently, posed a further problem. It was close to the route, but at a higher position than the railway, so that its existence would have been endangered with the slightest settlement. During the construction of the railway retaining wall, which was to be founded five to six meters deeper, neither water could be pumped out of the foundation pits nor could it be piloted - also because of the vibration. For this reason, cast iron well wreaths with a diameter of two meters were sunk, concreted out and the walls were first placed on top of them.

The extension of the gallery route along the Danube Canal, in turn, required a rescheduling of the connecting arch. In order to prevent too great a slope, this had to be extended to the north. It therefore no longer started directly at the Nussdorfer Straße station, but instead about 300 meters further on at a junction of the same name .

Participating construction companies

The following companies were involved in the construction of the light rail:

| Substructure and building construction: | Union-Baugesellschaft , Redlich & Berger, Wiener Baugesellschaft, Allgemeine Österreichische Baugesellschaft , Josef Prokop, Oettwert & Dittel, Doderer & Göhl, Alois Schuhmacher , Rabas & Rummel |

| Substructure: | Peter Kraus |

| Buildings: | Karl Brodhag, Friedrich Haas, Christian Speidel, Julius Stättermayer, Hans Schätz, Karl Stigler |

| Superstructure: | Franz Burian |

| Concrete structures: | Pittel + Brausewetter , Gustav Adolf Wayss |

| Pavings and roofing: | Lederer & Nessényi , N. Schefftel |

| Art locksmith work: | Kammerer & Filzamer |

| Gas and water pipes: | Karl Dumont, Teudloff & Dittrich Armaturen- und Maschinenfabrik |

| Mechanical facilities: | Anton Freissler , Stephan Götz & Sons, Josef Friedländer, Märky, Bromovsky & Schulz, C. Schember & Sons |

| Electrical facilities: | Siemens & Halske, Robert Bartelmus & Co. |

| Iron structures: | Anton Biró , Albert Milde , Ignaz Gridl , Rudolph Philip Waagner , Prague Machine and Bridge Construction Company of the First Bohemian-Moravian Machine Factory , Archducal Industrial Administration Teschen (Karlshütte), Witkowitz Mining and Ironworks Union , Škodawerke Actiengesellschaft , Breitfeld, Daněk & Co. |

Albert Milde himself also mentions the Prager Maschinenbau-Aktiengesellschaft, vorm. Ruston & Co. , the Prašil brothers , the Österreichisch-Alpine Montangesellschaft and the Zöptau trade union as other bridge construction companies involved in the construction.

From the opening to the takeover by the municipality of Vienna

Grand opening

After successful staff training trips, which took place from May 3rd to 5th on the suburb line and after the official ceremony on May 26th and 27th on the Upper Wientallinie and the belt line, the Viennese Stadtbahn was officially opened on May 9th, 1898 in Michelbeuern become. In addition to Emperor Franz Joseph I, the Viennese Archbishop Anton Josef Cardinal Gruscha , Imperial and Royal Railway Minister Dr. Heinrich von Wittek, the Lower Austrian Land Marshal Joseph Freiherr von Gudenus (1841–1919) and the Mayor of Vienna Karl Lueger . On that day the monarch drove with the kuk court salon train , which consisted of his saloon car and three other cars, from Michelbeuern over the belt line to Heiligenstadt, then over the suburb line and the western line to Hütteldorf-Hacking, then over the upper Wientall line to Meidling- Hauptstraße and finally on the belt line to the Alser Straße stop , with which he traveled to all sections completed by then. According to another source, the premiere drive again ended in Michelbeuern. In the last car of the special train, the Kaiser had a viewing platform; only there he was spared the smoke of the steam locomotive. The following quote from the emperor has come down to us from that ceremony:

"Created by the harmonious cooperation of the autonomous Curiae and the state, this railway construction will - as I confidently hope - bring the population manifold advantages and effectively promote the prosperous development of Vienna, which is dear to me."

After the London Underground (1863), the Liverpool Overhead Railway (1893), the Budapest Földalatti (1896) and the Glasgow Subway (also 1896), the Viennese light rail system was the world's fifth express transport system that ran - at least partially - underground . Vienna, for example, overtook Paris (1900), Berlin (1902) and New York (1904). The total construction and installation costs for the closer network of the light rail ultimately amounted to around 138 million crowns .

Hasnerstrasse was the only street that was cut through by the Stadtbahn. The city administration, which during the construction process insisted that no urban “communication” should be interrupted, only allowed this one exception.

Operating agreement

The steam light railway was operated by the Vienna State Railway Directorate on behalf of and for the account of the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna . The latter was considered a private railway, which also owned part of the rolling stock used on the light rail, but did not carry out any transport services itself . The light rail operation was initially carried out in accordance with the protocol of April 23, 1898 "regarding provisional provisions on the management of the successive opening of the sections of the belt line, suburb line, Wiental line and Danube canal line of the Vienna light rail by the Imperial and Royal State Railway Administration". In return, it received the entire operating income of the tram, the rent and lease interest from real estate and land as well as the income from the use of the industrial tracks and towing tracks connected to the tram . This agreement was only approved by the Ministry of Railways on the first day of regular operation, May 11, 1898, and was valid until the end of 1901.

However , the two partners did not conclude the final affiliation and operating agreement until June 25, 1902, which then came into effect retrospectively on January 1, 1902. According to this, the Commission for Transport Systems of the State Railways reimbursed the cost of running the operation in accordance with the "regulation concerning the determination of the incomes and expenses of the Viennese Stadtbahn and their offsetting" integrated in the contract. This agreement was initially valid until December 31, 1911. The dissolution of the kk building department for the Wiener Stadtbahn by decree of June 23, 1902 followed on June 30, 1902. The transactions still to be carried out were partly the redemption commissioner of the Wiener Stadtbahn and partly the CW section transferred to the kk construction management of the Wiener Stadtbahn.

Gradual start of regular operation

The closer network of the steam light rail system finally started its regular operation as follows:

| date | Surname | route | concession | Overall length | Operating length | Intermediate stations | Mean station distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 11, 1898 | Suburban line | Penzing - Heiligenstadt |

Main line | 9.949 kilometers |

9.584 kilometers |

six | 1369 meters |

| June 1, 1898 | Upper Viennese line | Hütteldorf-Hacking - Meidling-Hauptstrasse |

Local railway | 5.879 kilometers |

5.409 kilometers |

five | 902 meters |

| Waistline | Meidling main street - Heiligenstadt |

Main line | 8.888 kilometers |

8.407 kilometers |

without Michelbeuern: seven with Michelbeuern: eight |

without Michelbeuern: 1051 meters with Michelbeuern: 934 meters |

|

| Suburban line | Heiligenstadt - Brigittenau-Floridsdorf |

Main line | 1.357 kilometers |

2.028 kilometers |

no | 2028 meters | |

| June 30, 1899 | Lower Viennese line | Meidling-Hauptstrasse - main customs office |

Local railway | 5.650 kilometers |

5.443 kilometers |

five | 907 meters |

| August 6, 1901 | Danube Canal Line | Main customs office - Heiligenstadt |

Local railway | 5.874 kilometers |

5.632 kilometers |

four | 1126 meters |

| Connecting bow | Junction Nussdorfer Straße - Brigittabrücke |

Local railway | 1.235 kilometers |

1.415 kilometers |

no | - |

Note 1: the length specification of 2.028 kilometers for the Heiligenstadt - Brigittenau-Floridsdorf section also includes the 0.260 kilometer current route to the middle of the waiting hall of the Brigittenau-Floridsdorf station, which was used together with the Donauuferbahn.

Note 2: The Heiligenstadt – Brigittenau-Floridsdorf section was originally intended only for freight traffic and should actually become part of the external network. On the occasion of the anniversary exhibition in the Prater in 1898 , which lasted from May 6th to October 18th, 1898, however, it then also showed passenger traffic from the start.

The Untere Wientallinie, the Obere Wientallinie and the Donaukanallinie were, in this order, continuously kilometers and had their common zero point in Hütteldorf-Hacking. The suburb line and the belt line were also kilometers upwards in the direction of Heiligenstadt; they had their zero points accordingly in Penzing and Meidling-Hauptstrasse. The connecting curve in turn took over the kilometering of the belt line at the Nussdorfer Strasse junction, which means that its zero point was Meidling-Hauptstrasse. On the elevated railway lines, the kilometrage was displayed on cast-iron square boards with a red border. They were attached to the railings parallel to the direction of travel.

With a length of only 517 meters, the Alser Straße – Michelbeuern section represented the shortest distance between stations for the light rail system, while the Brigittabrücke – Heiligenstadt connection, at 2590 meters, was the longest section in the narrow light rail network. The mean station distance was 620 meters.

In the course book , the two Wiental lines, the belt line and the section Hauptzollamt-Praterstern of the connecting line were to be found under table number 1b, while the outer belt line was number 1c, the suburb line was number 2 and the section Hütteldorf-Hacking-Hauptzollamt of the connecting line was number 2a was assigned. From its opening in 1901, the Danube Canal line and the connecting arch were listed under 1b, while the main customs office-Praterstern received the new table 1d.

When the route was opened, the operator intentionally chose the simplest possible names for the individual route sections. They differed in part from those from the planning phase, including the division of the Wientallinie into an upper and a lower section. The names should not only simplify internal communication, but also serve to provide an easier overview and convenience for the audience.

For light rail accidents , the Vienna Voluntary Rescue Society also put a special railway ambulance into operation in 1900 , which was stationed at the main customs office.

First electrification attempt in 1901

In view of the problems with steam operation that became apparent early on, those responsible considered electrifying the Vienna light rail as early as 1897, when the last sections were still under construction. Ultimately, Siemens & Halske did not begin to prepare for a trial run with electric multiple units , which were made up of up to ten - appropriately adapted - regular light rail vehicles . For this purpose, the engineers selected the 3.8 kilometer stretch between Heiligenstadt and the Michelbeuern freight station; a total of 8.5 kilometers of track had been electrified by spring 1901 and a temporary hall was built in Heiligenstadt for the maintenance of the test trains.

The first test drives took place in July 1901 without passengers during the nightly shutdown between 1:00 and 4:00 a.m. The maximum speed was 45 km / h, the journey time was nine minutes south and eight minutes north. Since the test drives were successful, the kk Staatsbahndirektion also permitted day trips without passenger transport from July 1, 1902, which were completed according to a fixed timetable with four daily train pairs. However, for financial reasons, the experiment ended soon afterwards, and no economic advantage over steam operation could be determined. The last trip took place on July 12, 1902 in the presence of the representative of the railway minister, Ritter von Pichler, representatives of the Commission for Transport Systems and numerous journalists; the electrical systems were dismantled by 1906.

In the first attempt at electrification, the London-style tracks were provided with a U-shaped conductor rail running centrally between the rails . It had a cross-section of 44.4 square millimeters, was mounted on insulators made of porcelain or hard rubber that were screwed to the sleepers and protruded 40 millimeters above the top of the rail. Wooden planks were attached to the side to protect against accidental contact. The third rail was interrupted at points, crossings and crossings and connected by cables laid underground. At both ends of a busbar section, wooden run-up pieces for the busbar current collectors were attached.

The test route was supplied with 500 volts direct current by the Engerthstrasse steam power plant of the Allgemeine Österreichische Elektrizitätsgesellschaft (AÖEG) via two feed points in the Währinger Strasse and Nussdorfer Strasse stations. The return circuit respectively Earthing carried by the rails, the gelaschten rail joints were bridged with copper connectors. During the electrification test, the insulating rails of the block device were exchanged for mercury bending contacts.

Second electrification attempt in 1906

The Prague company Křizík & Co made a second attempt at electrification between the main customs office and Praterstern stations between 1906–1907. For this purpose, Křizík built his own substation , which fed the line with two times 1500 volts direct current in a three-wire arrangement, whereby the rails were required as a central conductor in addition to the double-pole overhead line . A two-axle locomotive with a central driver's cab was used as the test vehicle , which was designated as VIENNA 1 and later went to the Czechoslovak State Railways .

First World War

The outbreak of the First World War was a severe setback for the light rail system. Their entire network was now actually used for troop transports for the military, and civilian passenger transport was temporarily only possible with restrictions. However, she was able to fully fulfill her military task. Immediately after the outbreak of war, the Stadtbahn had to surrender ten locomotives and 413 cars, and in 1915 another 22 locomotives. In October 1914, 461 light rail vehicles were already in service with the army.

Another reason for the limitation of the operation was the lack of personnel, as more and more employees their convening received. As a replacement, women had to be employed on the tram for the first time from June 1915, as was previously the case with conductors on the tram. However, they only took over the station services. In order to ensure that the changeover was as quick and smooth as possible, the administration only engaged the wives and daughters of male employees.

As a result of the general mobilization of July 31, 1914, light rail passenger traffic was completely stopped for the first time between August 6 and August 25, 1914. From August 26 to August 31, 1914, operations only took place in the morning, noon and evening for a period of two to three hours. From September 1, 1914, this so-called group traffic was extended to all hours of the day from 5:15 a.m. departure in Hütteldorf-Hacking to midnight arrival there. On September 15, 1914, limited passenger traffic followed on the connecting railway with a transition from and to the Danube Canal line, which lasted until May 25, 1915. From May 26, 1915 to June 11, 1915, passenger traffic on the entire light rail and connecting tramway was completely stopped for the second time, before limited passenger traffic in the morning, noon and evening hours to the again from June 12, 1915 Duration of approximately three hours was offered.

Extensive cessation of operations on December 8, 1918

Less than a month after the end of the war, the light rail system had to be almost completely shut down again on December 8, 1918 due to a lack of coal and because the operating resources were needed for other purposes. The coal now had to be imported at great expense from the mining districts lost in the war ; it was no longer possible to raise the daily amount of 240 tons. Only the connecting railway and the suburban line remained in operation almost continuously - both during and after the war, albeit at times heavily thinned out.

In addition, even after the extensive cessation of passenger traffic, goods traffic continued between Heiligenstadt and the main customs office on the one hand and between Heiligenstadt and Michelbeuern on the other. Meanwhile, the unused reception building served other purposes. At that time, the Karlsplatz station was home to a ticket sales office for the Austrian Travel Agency in order to save the city public from having to go to the train stations if they wanted to buy tickets before the day of travel. Other station buildings on the Wientallinie were used by foreign railway workers who came to the capital for meetings and negotiations on official matters and found accommodation only with difficulty and at high cost, for a relatively small fee as a place to stay. For this purpose, the service and waiting rooms, if they were suitable, were equipped with iron beds and the most necessary furnishings so that they met the modest demands. In other reception buildings nearby offices established offices and a considerable part of the other light rail buildings served as storage space for goods or as food stores for the railway organizations.

Disinterest of the operator after the collapse of the monarchy

As a result of the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, which took place in autumn 1918 and was confirmed in peace treaties in 1919/1920, the earlier military considerations in connection with the Vienna light rail system no longer played a role. In addition, the Federal Constitution passed on November 10, 1920 and the separation law of December 29, 1921 based on it , ensured that the municipality of Vienna was separated from the federal state of Lower Austria, so that from then on two federal states had to coordinate with each other for light rail traffic to the Vienna area.

In the meantime, the attitude of the politicians towards the Vienna Stadtbahn had changed fundamentally, whereby the changed political majority in the Vienna City Council and Landtag , in which the Social Democrats dominated from then on, contributed to a large extent . In this context, the improvement of living conditions, and thus also of the transport facilities, had become a first-rate local political issue in Vienna. At the same time, also for political reasons, the interest of the other bodies involved in the Stadtbahn fell. Because the federal government, the state of Lower Austria and the state railway were in opposition to the social democratic government of Vienna. The previously weak federalism struck with all its might and prevented a generous transport solution for Vienna and the surrounding area.

Due to the new peripheral location of Vienna in the still young Republic of Austria, the traffic flows had changed significantly, especially traffic to the north and east collapsed almost completely. In addition, as a result of the war, the population of the capital fell for the first time in history. The prospect that Vienna would grow to four million inhabitants was no longer realistic. Hence - from the point of view of the operator at the time - no profitable light rail traffic was to be expected. Furthermore, as feared at the opening, the smoke gases from the steam operation had over the years severely damaged the reinforced concrete ceilings and metal girders in the flat tunnels on the Wiental and Danube Canal lines. As a result, the light rail infrastructure was in poor condition after the end of the war. The tunnel ceilings then had to be repaired with the so-called Torkret method , i.e. the use of sprayed cement . Because there was a lack of both money and material, the state railroad contented itself with removing the wear and tear by keeping the lines only sparse.

Establishment of a provisional transfer traffic

After the planned electrification of the Stadtbahn was delayed, steam light rail trains ran provisionally again from June 1, 1922 on the Upper Wiental Line and the Belt Line, initially 25 pairs of trains a day. On that day, due to the increased passenger traffic as well as to relieve the tram, the Westbahnhof and the Franz-Josefs-Bahnhof, the state railway set up a so-called transfer traffic in the relation Hütteldorf-Hacking - Heiligenstadt and back. Most of these trains ran continuously from Neulengbach, Rekawinkel or Purkersdorf via Meidling-Hauptstraße to Kritzendorf, St. Andrä-WIERT or Tulln and vice versa, later the frequency was increased to 37 train pairs per day.

The trains of the transition traffic only served selected intermediate stations, these were Unter St. Veit-Baumgarten, Hietzing, Meidling-Hauptstraße, Gumpendorfer Straße, Westbahnhof stop, Währinger Straße and Nussdorfer Straße. The tariff of the state railway was applied, whereby the following stations were treated equally: Under St. Veit-Baumgarten for Baumgarten, Hietzing for Penzing, Meidling-Hauptstraße, Gumpendorfer Straße and the Westbahnhof stop for Vienna Westbahnhof as well as Währinger Straße and Nussdorfer Straße for Vienna Franz -Josefs-Bahnhof. For the route Westbahnhof - Währinger Straße an additional fare of 160 kroner in the second class or 80 kroner in the III. Class are paid.

When the summer timetable came into effect on June 1, 1923, the trains of the transfer traffic also stopped in the stations Ober St. Veit and Josefstädter Strasse, but the station Nussdorfer Strasse was omitted and the frequency was reduced to 32 daily train pairs. From January 1924, the state railway only served the Hütteldorf-Hacking-Meidling-Hauptstrasse-Michelbeuern route as a branch line , with passengers only being transported to and from the Alser Strasse station. With the end of the summer timetable on September 30, 1924, the transfer traffic finally ended completely as a result of the ongoing electrification work.

From the steam light rail to the subway

After the full integration of the Stadtbahn into the tram network, originally planned by the municipality of Vienna, was discarded in the course of 1923, the Vienna Electric Stadtbahn , or WESt for short , was also available . Formally a classic railway. After the comparatively rapid electrification and numerous smaller adaptations, it went into operation in stages between June 3, 1925 and October 20, 1925. From the latter date, the new community tariff for the tram also applied, which brought the new means of transport an economic success.

From 1925 the electrified network was completely separated from the rest of the railway network and instead linked to the urban tram network at two points by the mixed-operation line 18G . Classic two-axle tram cars, which had been the trademark of the electric light rail over the decades, were used - also in pure light rail traffic. The new operator built three new depots in Michelbeuern, Heiligenstadt and Hütteldorf-Hacking for the 450 railcars and sidecars purchased at the time, and hired 823 new employees for the new branch of the company.

The dissolution of the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna in 1934 finally sealed the end of the existence of the original steam light rail. Thereupon the municipality of Vienna also took over the infrastructure of the electrified network, which from then on was only licensed as a small railway without freight traffic, while the suburban line fell completely to the state railway. The Second World War also hit the electric light rail system hard, especially in the final year of the war in 1945; it was not fully reactivated until 1954. In the 1960s at the latest, the light rail system was subject to a modernization jam because the subway planning was only progressing slowly at the time. It was not until 1976 that the first section of the Stadtbahn could be converted to underground operation. On October 7, 1989, the two belt lines G and GD, which are the last two light rail lines at all, received the new U6 line signal. This ended - apart from the remaining infrastructure - the history of the Vienna light rail system after 91 years.

From the steam light rail to the S-Bahn

Regular passenger traffic on the steam light rail on the suburban line ended on July 11, 1932, which is why the second track was removed from 1936. However, freight traffic was retained. In addition, the summer bath trains ran until August 27, 1939, when they no longer served the Ober-Döbling and Unter-Döbling stops . In the years 1950 and 1951, then stretch again toured the largely undamaged during World War II, baths trains . It then fell into disrepair and was partially completely out of order. It was not until 1979 that the municipality of Vienna, the Austrian Federal Railways and the federal government agreed to revive it. So the suburban line was finally electrified, expanded to double-track again and converted to drive on the right. The stations Ober-Döbling and Breitensee as well as the originally non-existent Krottenbachstraße stop were rebuilt, while Unter-Döbling remained permanently open. On May 31, 1987, passenger traffic was finally resumed with the S45 line.

The Hauptzollamt – Praterstern connection has been part of the main S-Bahn line since 1959, the busiest section in the Vienna S-Bahn network, and has been electrified since 1962. Today it is served by lines S1, S2, S3, S4 and S7. The Radetzkyplatz station has not been in operation since the interwar period and was razed after the Second World War.

On the Western Railway, in turn, the light rail trains were replaced by the so-called Purkersdorfer Pendler after the First World War , which, however, did not start operating until May 1931. This shuttle service between Hütteldorf-Hacking and Unter Purkersdorf existed until May 27, 1972. As late as 1944, for example, this relation was listed under the separate course book table 459e, with a rigid 30-minute cycle throughout the entire operating time. At times it even drove every 15 minutes. In the meantime, the Hütteldorf – Neulengbach section of the Westbahn electrified in 1952 is served by the S50.

The Franz-Josefs-Bahn to Tulln is now used by the S40, this section has been electrified since 1978.

Problems, criticism and controversy

Criticism of the steam operation

From the beginning, the steam operation was heavily criticized by both experts and the population. Even when it opened in 1898, the concept of a steam-powered subway was considered technically out of date. Otherwise there was only one in London, where the City and South London Railway ran electrically from 1890 , before all older lines were converted between 1901 and 1908. All other underground railways around the world, on the other hand, were electric from the start or, as in Glasgow, were operated as a cable car or, as in Istanbul and Lyon , as a funicular .

But not only on the long stretches of Vienna tunnels, but also above ground, the use of steam locomotives in the densely built-up urban areas was a nuisance. The steam operation contradicted the goal of a hygienic way of life in the big city, which is why the architect and urban planner Eugen Fassbender criticized at the time:

"... that now the locomotives stiffen the air day and night, while here [meaning the newly developed belt road] a strip of green Angers , which is highly desirable for sanitary reasons, could have been preserved."

The Illustrierte Über Land und Meer expressed its criticism as follows:

“Now the Viennese can take the long-awaited tram from the heart of the city - from the opera building, for example - to the wonderful Vienna Woods in a few minutes ; he will not be able to move his home from the big city gears to the rural surroundings of the city just for the summer in order to live with his family in better hygienic conditions. "

The steam light rail operation also exposed passengers and train staff to the smoke on the underground sections largely unprotected . The dreaded plague of smoke was particularly noticeable in the tunnel between the Chain Bridge and the city park. The flat, rather than curved, tunnel ceiling turned out to be problematic, as this enabled the smoke to settle in the corners, which made ventilation very difficult. In addition, the soot settled on the seats and soiled them, and with it the passengers' clothing, even before the journey began. In addition, the locomotives also damaged the infrastructure of the light rail itself, because the smoke or combustion gases accelerated the corrosion of the exposed iron construction parts and the superstructure and generated dust that penetrated the cars. The problem of rusting was exacerbated by the steam that escaped from the locomotive and, in winter, from the heating cables . The resulting heavy mass of smoke and steam could only escape very slowly from the tunnel sections due to the dense train sequence in both directions, especially in cloudy and foggy weather. In the Ferdinandsbrücke station, the operator even experimented with powerful fans at times to bring the smoke to the surface before it exited the underground station, but these attempts were only very unsuccessful.

In addition, the white plastered station buildings in particular quickly became soiled. The facade of the Hietzinger Hofpavillon had to be repaired for the first time three years after it was opened. But all surrounding buildings were also affected. This problem became particularly apparent when looking at the marble statues of the former Elisabeth Bridge . After the bridge was demolished in 1897, they were first erected at Karlsplatz station. There they polluted so quickly that they were nicknamed The Eight Chimney Sweeps among the population and had to be transferred to Rathausplatz as early as 1902 . Only in midsummer did the exhaust emissions not pose a problem; at 30 degrees Celsius and 19 degrees Celsius in the tunnels, the locomotives were almost smoke-free.

The steam light railway right outside their front door was also not particularly popular with the residents, as the satirical weekly magazine Kikeriki scoffed in May 1898, when it opened:

“How did B. become deaf so suddenly? He had his apartment window open on his belt for half an hour! "

And the relatively low speed of the steam trains also inspired the humorists:

"Why do you have such a sad face? My hat, stick and glasses fell out of the wagon from the express train of the light rail during the fastest journey! So what? And I could only pick up the stick and glasses! "

Ultimately, the Vienna Stadtbahn was built too late as a steam train and too early for electrical operation. Only the lower building costs and the strategic military function of the light rail spoke in favor of steam operation. The chosen form of operation appeared to be more flexible in this regard, because in Central Europe there was no network of electrified railway lines for decades.

Strategic railway with limited benefits for the population

Ultimately, the routing of the Vienna Stadtbahn was strongly influenced by the above-mentioned military considerations, so it had the character of a strategic railway . This was especially true after the reduction of the project in 1895 and 1896, in which only sections of little military relevance were omitted. The same applied to the omitted intermediate stations, which were also of no importance for the army - but significantly reduced the utility of the light rail for the population.

However, the military-strategic importance of the light rail was for a long time - by contemporary and later authors - often overrated. In fact, it was a multifunctional railway in its concept and design, which served the inner-city area as well as local transport in the summer on the Franz-Josefs-Bahn and the Westbahn, which could also be used for freight transport and, in a strategic emergency, for troops and Material transport. The military argument was deliberately used to justify the high state share in the financing of a light rail system for the imperial capital, for example to the Czechs and Hungarians.

Regardless of the strategic function, the choice of location of the stations was not always a good one; in terms of location and structure, they did not always meet the needs of urban mass traffic. The Karlsplatz stop would have been better placed between Getreidemarkt and Kärntner Straße instead of on Akademiestraße, and a Schwarzenbergplatz stop would have been more advantageous than the one in the extended Johannesgasse near the city park. Likewise, the access to the main customs office, which was from Henslerstrasse instead of Landstrasse Hauptstrasse , was unfavorable. At Karlsplatz and Schwedenplatz, on the other hand, the station pavilions were presumably aligned with the expected new road from Akademiestraße-Laurenzerberg, which however was not realized. As a result, they came to be located away from the main traffic flows in Wiedner Hauptstrasse and Rotenturmstrasse . The way of the passengers was often lengthened by the fact that the stops in the lower position usually only had one entrance or exit. This means that if someone got off at the end of the train at the end of the train at Kettenbrückengasse, for example, and wanted to continue in the opposite direction, they still had to make a detour of around 200 meters.

The conception as a strategic railway, however, resulted in the massive construction of the routes required by the military and the high load-bearing capacity of the bridges, which decades later accommodated the conversion to underground operation. In addition, the planning was based - in the tradition of main railways - more towards favorable topographical opportunities such as the two rivers and the former line wall, but did not correspond to the actual municipal transport needs. In the end, the light rail system remained a torso because there were no radial lines directly into the city center, instead one that ran around the city center on three sides and two parallel tangential lines on the western edge of the city . So the journalist coined Eduard Pötzl even at the light rail opening the derogatory term round-the-city train , which later dictum in the vernacular was:

“Berlin and Paris have a light rail, Vienna a round-the-city train. "

Other critical titles were "military track" and "artificial track". Originally, the Stadtbahn was also intended as a stimulus for residential construction, in which the important radial lines should have opened up old and new residential areas . However, due to the omitted sections of the route, it could not do justice to this task. Nevertheless, the steam light rail ran through the majority of the 20 municipal districts that existed around the turn of the century and had at least one station in each of them. Only the VI. District Mariahilf , VII. District Neubau and XIV. District Rudolfsheim had no direct access to either the narrow or the outer light rail network.

Economic failure and competition from the electric tram

Ultimately, the Vienna Stadtbahn did not have the great success that was hoped for, not least because of the unpopular steam operation and the associated problems, and was never particularly popular with the population. Although it was not an outright failure of the project, it could never really meet the expectations placed in it and did not develop into a second-level means of mass transport. The main traffic areas of the patchy light rail network were on the one hand on the periphery and not in the center; on the other hand, the highest train density prevailed on routes that led through sparse settlements. One of the reasons for this was the cramped location of the Meidling-Hauptstraße station. Since it was not suitable as a turning station, and due to lack of space, no reversing track could be created in Hietzing, many trains had to be run to Hütteldorf-Hacking without any operational necessity. As a result, the Obere Wientallinie, which had by far the lowest passenger frequency on weekdays, was the busiest. But even there some trains could not return directly. Because the turnaround time in the turning stations was only nine minutes at the beginning, one was forced to run additional trains to Purkersdorf during rush hour.

Furthermore, the tickets for the steam light rail were comparatively expensive, a common tariff system with the cheaper trams did not exist until 1925. The fact that one was not allowed to change from the tram to the light rail without buying a new ticket was ultimately the decisive factor for many passengers in staying with the tram. The tariff reform of 1901, which reduced long tram journeys over eight kilometers by a third, did not bring any improvement in this regard.

Especially after the electrification of the tram, which began in 1897 and was quickly completed, the last horse-drawn tram already ran in 1903, the intervals of the light rail were longer than on the largely parallel tram, which at that time ran every two to five minutes. Apart from that, the tram also served a much more dense network and had much smaller distances between stops. In addition, wherever the tram ran, the tram also ran nearby. However, numerous station entrances of the tram were 100 to 200 meters away from the tram stops, which made it even more difficult to change trains. As early as 1904, Arthur Oelwein, one of the three site managers for the Stadtbahn, stated:

"If these trams had existed in their current layout [meaning the electric tram network] before the construction of the light rail began, the program for the light rail system drawn up in 1892 would probably have undergone a major change."

The tram line 8, so called from 1907, developed into a special competition for the light rail. It covered almost the entire belt line, but served about twice as many intermediate stations. Since there were no elevators or escalators in the tram stations at the time and there were up to 80 steps to climb, many passengers avoided climbing the stairs twice - especially on short routes - and instead opted for the tram. However, at least in winter, some passengers preferred the light rail due to their heated cars, while the first heated tram cars were not used until 1910 and the first sidecars with heating only from 1951. In general, passengers tended to cover longer distances with the light rail. In 1909, for example, the average travel distance on the tram was three to four kilometers, while on the tram it was 7.5 kilometers. The transfer traffic from the trains of the state railway was insignificant. In 1908, around 81,000 passengers a day arrived at Vienna's seven long-distance train stations, but only nine percent of them, that is 7,300 people, switched to the tram.

The lack of a connecting curve between the belt line and the lower Wiental line, in turn, had a negative effect on the operation of the light rail in the Gumpendorf area because no direct ring traffic from the belt to the Wiental, the Danube Canal and the belt was possible. The State Railways as the operator had approached the Commission for Transport Systems in this matter and studies were also being drawn up, but no agreement could be reached. On the one hand, the costs for the connecting curve Gumpendorfer Straße - Margaretengürtel were ten million crowns, and on the other hand, some experts expressed technical concerns about the project because it would have resulted in a gradient of 48 per thousand. Irrespective of this, however, there was limited ring traffic on the steam light rail, because some trains coming from Hütteldorf-Hacking ran continuously back to Hütteldorf-Hacking via Meidling-Hauptstrasse, Wiental, Danube Canal, Gürtel, Meidling-Hauptstrasse.

In the first eleven years of operation, the number of passengers on the Stadtbahn stagnated to a large extent - regardless of the then rapidly increasing population of Vienna - although 1902 was the first full year of operation of the entire network. The first decline in passenger traffic from 1902 to 1903 is a direct result of competition from the electric tram. Ultimately, the tram operation, which was unprofitable from the start, caused increasingly increasing deficits. This means that no investment reserves could be generated, especially for the increasingly urgent need for electrification. In the first eleven years of operation, the economic situation developed as follows, although the first full financial year was not until 1899 :

| year | Transported people | Medium travel route | Passenger kilometers | Income in Austrian crowns |

Issues in Austrian crowns |

Deficit in Austrian crowns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898 | 6,922,382 | 6.54 kilometers | 45.238.620 | 1,218,616 | 1,531,828 | 313.212 |

| 1899 | 19,046,337 | 5.88 kilometers | 111.964.211 | 3,357,396 | 3,873,252 | 615.856 |

| 1900 | 28.245.436 | 4.47 kilometers | 126.128.082 | 4,681,518 | 4,833,203 | 151,685 |

| 1901 | 32.222.266 | 5.53 kilometers | 178.218.844 | 5,333,851 | 5,520,323 | 186,472 |

| 1902 | 33,807,873 | 7.08 kilometers | 239.395.531 | 6,453,874 | 5,911,599 | 457.725 |

| 1903 | 32.012.240 | 7.39 kilometers | 236.590.860 | 5,287,042 | 6,918,663 | 546.996 |

| 1904 | 29,953,067 | 7.36 kilometers | 220.522.560 | 5,158,039 | 6,001,844 | 843.805 |

| 1905 | 29,649,077 | 7.25 kilometers | 214.925.643 | 5,387,899 | 5,811,859 | 423.960 |

| 1906 | 31,147,771 | 7.74 kilometers | 241.157.604 | 5,669,392 | 6,393,437 | 724.045 |

| 1907 | 33,703,566 | 7.26 kilometers | 244,641,828 | 5,673,621 | 7.007.731 | 1,334,110 |

| 1908 | 32,490,582 | 7.17 kilometers | 232.876.914 | 5,667,620 | 7,253,377 | 1,590,757 |

In 1909, at least 34.4 million passengers were carried, and by 1913 the operator finally managed to increase this number to 47 million. This meant that the Stadtbahn was still far behind the competing trams, which were able to increase the number of its transport cases from 133 to 323 million annually between 1902 and 1913 alone.

Viewed overall, the steam light rail system only played a subordinate role in inner-city traffic. While in 1910 the respective rapid transit trains in Paris already reached 22 percent , in Boston 29 and in New York even 36 percent of the frequency of all public transport, in Vienna this share was only eleven percent. In 1903, on the other hand, the share of the light rail system was still 15 percent, while the tram came to 74 percent and the Stellwagen to eight percent.

The low average occupancy of Vienna's light rail trains in turn led to relatively high operating costs . While the Paris light rail system, which was particularly successful in this regard, only spent five pfennigs for each passenger carried in 1905 , this value in Vienna was 16 pfennigs. The comparison with regard to vehicle kilometers is similar . Of the eleven light rail vehicles examined, the Viennese system took last place with only 1.8 passengers per car-kilometer, while the first-placed London Waterloo & City Line , for example , came in at 7.9 passengers per car-kilometer. In addition, the operating expenses for steam operation, again based on the vehicle kilometers, were by no means lower than for the comparable electric railways of that time.