Vienna electric light rail

| Vienna electric light rail | |

|---|---|

|

Signs for a platform access

| |

|

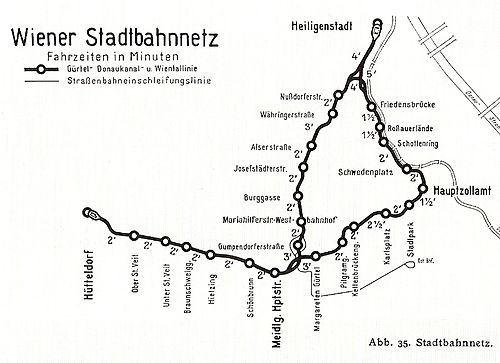

Network plan from 1937

| |

| Course book range : | 1, 11 |

| Route length: | Pure light rail routes: 25.559 km. Connecting tracks to the tram network: 0.892 km |

| Gauge : | 1435 mm ( standard gauge ) |

| Power system : | Overhead line, 750 volts = |

| Maximum slope : | 25 ‰ |

| Minimum radius : | 150 m in the open, 22 m in loops |

| Top speed: | up to January 2nd, 1984: 40 km / h, from January 2nd, 1984: 60 km / h |

| Dual track : | continuous |

| Opening: | June 3, 1925 |

| last day of operation: | October 6, 1989 |

| Original operator: | Municipality of Vienna - urban trams (WStB) |

| Operator from November 29, 1942: | Wiener Verkehrsbetriebe (WVB) |

| Operator from January 1, 1949: | Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe (WStW-VB) |

| Stations: | 27 |

| Operational stations : | three |

The Viennese electric light rail , abbreviated WESt , WESt. , Wr.-E.-St. or WEST. , was a local public transport system in the Austrian capital Vienna , which existed under this name from 1925 to 1989. The standard-gauge urban rapid transit system , which was initially classified as a railway , emerged from the original Viennese urban railway , which opened in 1898, was designed by Otto Wagner and operated with steam locomotives , and which in some cases also served suburbs.

In contrast to its predecessor, the electric light rail was no longer operated by the kk Staatsbahnen , but by the municipality of Vienna - urban trams (WStB), from which the Wiener Verkehrsbetriebe (WVB) in 1942 and the Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe (WStW-VB ) in 1949 ) emerged. In addition, it was no longer linked to the national railway network, but instead was linked to the Viennese tram and was also served by tram vehicles that were only slightly adapted . This form of operation with tramcars in Vielfachsteuerung and trains with up to nine two-axle as a standard gauge railway trassierten routes was unique in the world. The electric light rail, on the other hand, formed the cornerstone for the Vienna underground , which opened gradually from 1976 and in which it was finally incorporated.

history

prehistory

When the Wiener Dampfstadtbahn went into operation in 1898 after a planning phase of more than 50 years, it was only able to meet the expectations placed on it to a limited extent. Their routing primarily linked the main lines approaching Vienna and largely corresponded to the strategic needs of the military and served to relieve the major terminal stations . The passenger transport needs of the Austrian capital were not adequately covered by its incomplete and never completed network. In addition, the original light rail could not prevail economically against the cheaper and more frequent trams and caused increasing deficits year after year. Furthermore, the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna , the formal owner of the Stadtbahn, never agreed a collective bargaining agreement with the tram.

The unpopular steam operation was already considered technically obsolete when it opened and caused problems for residents, passengers and the infrastructure itself in many ways. After two unsuccessful attempts at electrification in 1901 and 1906, the First World War ultimately prevented the urgently needed modernization of the light rail. After the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy , the state largely lost interest in the light rail system as a result of the major changes in the military and transport conditions, and the economic crisis in the post-war period made matters worse. The steam light rail service largely ended on December 8, 1918 due to a lack of coal, only the suburban line remained in operation.

Takeover of the Stadtbahn by the municipality of Vienna

Offer to the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna in the summer of 1923

As a result of the state railway's lack of interest in the inner-city light rail routes, the municipality of Vienna tried itself in the early 1920s to restore the largely idle transport infrastructure. In addition to municipal housing , it became one of the major projects in Red Vienna . Because after living conditions increasingly normalized and the mobility of the Viennese population increased again, the extensive standstill of the tram led to an overload of the tram, which at that time had to carry all traffic.

To improve the situation, the then Mayor of Vienna, Jakob Reumann, submitted an offer to the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna on August 23, 1923 to take over around two thirds of the narrower urban railway network free of charge for 30 years, for which the city administration undertook to electrify and electrify the routes in question operate on their own account. In detail, there were the following five subsections:

| Surname | route | concession | length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waistline | Meidling-Hauptstraße - Nussdorfer Straße junction - Heiligenstadt | Main line | 8.317 kilometers |

| Lower Viennese line | Meidling-Hauptstrasse - main customs office | Local railway | 5.450 kilometers |

| Upper Viennese line | Hütteldorf-Hacking - Meidling-Hauptstrasse | Local railway | 5.334 kilometers |

| Danube Canal Line | Main customs office - Heiligenstadt | Local railway | 5.304 kilometers |

| Connecting bow | Junction Nussdorfer Straße - Brigittabrücke | Local railway | 1.154 kilometers |

The municipality of Vienna had previously provided the necessary material loan of 185 billion Austrian crowns or 18.5 million schillings as part of emergency work for the electrification . The previous links with the Westbahn and the Franz-Josefs-Bahn could no longer be taken into account for cost reasons. However, in the last year of peace, 1913, of the 41.2 million passengers on the inner-city routes, only 6.25 million drove out or came from there via Hütteldorf-Hacking and Heiligenstadt . Likewise, the municipality of Vienna was not interested in the comparatively little frequented suburban line on the outskirts, especially since it was still necessary for the so-called transfer traffic between the main lines. The same applied to the connecting railway Praterstern – Hauptzollamt – Meidling , the connecting railway Penzing – Meidling , the Donauländebahn and the Donauuferbahn . Although they were also still in the city, they belonged to the so-called outer network of the steam light rail .

Originally planned full integration into the tram network

According to the plans of the then tram director, engineer Ludwig Spängler, which were valid in the summer of 1923, the above-mentioned five routes were to be provisionally - that is, until the planned electrical full-line operation or integration into a future subway network - as an electric tram with driving on sight and in the city network The usual voltage of 600 volts direct current can be operated. This would have resulted in a complete merger with the tram network.

The tram cars, which had become redundant due to the weaker traffic since 1918, were intended as means of transport on the light rail. These included above all the 90 type L railcars built between 1918 and 1921 as well as matching sidecars of types m (from 1930 k 3 ) and m 1 (from 1930 k 4 ). Because of the strong inflation in the post-war period, the tram had to contend with a significant drop in frequency in the second half of 1922 and in the first half of 1923. The number of passengers carried fell from around 520 million in 1921 to 440 million in 1922 and increased only insignificantly in the first half of 1923. Thus, at the time of the takeover offer by Stadtbahn, numerous trams were redundant. With them, a maximum speed of only 30 to 33 km / h would have been possible, but this was still considered to be more sensible than the ongoing cessation of the Stadtbahn, which would have remained for years without the intervention of the municipality of Vienna.

Above all, however, the municipality of Vienna planned in 1923, in view of the sometimes negative experiences with the heavy excursion traffic on the steam light rail , a large part of its vehicle fleet during the week in tram traffic and on the afternoons on beautiful Sundays and holidays in the midsummer freshness - and bathing traffic on the light rail to use. Depending on the weather, it was around ten to twenty days a year on which up to three times more passengers had to be carried than usual. The new operator expected around 12,000 passengers an hour on the route to Hütteldorf-Hacking alone at peak times. The advantage here was that the busiest tram traffic times were May, October, the cemetery traffic on All Saints' Day on November 1st and the winter months in snowy years, while their frequency was lower in the months June to September. However, it was precisely in these midsummer months that the traffic peaks for the light rail vehicles fell. Only in a very hot June could there be a simultaneous large demand for cars in both parts of the company, provided that this was already an option for the Danube baths. In June, tram traffic showed a significant decrease in frequency. In addition, experience has shown that the least operational damage occurred to the trams in early summer, which means that the tram could for a short time get along with the smallest permissible vehicle reserve.

The tram cars used on the light rail would have been only slightly adapted, the replacement of the lyre pantographs with pantographs and the installation of compressed air brakes were planned . Director Spängler considered the use of trams in the light rail network to be permissible, because the majority of the passengers to be gained for the light rail system were to be withdrawn from the tram. At that time, on the other hand, they only wanted to procure new wagons for day-to-day operations on the light rail routes, plus a reserve. So it seemed possible to limit the costs for the electrification of the tram to the lowest possible level, especially since the use of a common fleet of vehicles would also have reduced the costs for coach houses and workshops.

Criticism of the demotion to the tram

From the beginning, the electrification of the tram in the 1920s was only intended as a provisional measure, which was not intended to anticipate the later introduction of full-line electric rail operations. Nevertheless, the conversion of a railway line to tram operation with driving on sight and the separation from the railway network remained controversial among experts. One of the opponents of such a solution was the electrical engineer Carl Hochenegg , who in turn worked out an alternative concept in 1923. This also envisaged operation by the municipality of Vienna, but the light rail should be operated with 1500 volts direct current and independently of the tram. Hochenegg proposed trains of up to three three-part railcars with partially lowered floors , which should go beyond the main network to Purkersdorf , now Unter Purkersdorf, and Kritzendorf . Here, up to a four-track expansion of the Franz-Josefs-Bahn, route usage fees would have to be paid to the state railway.

Rescheduling from autumn 1923

The further upswing in traffic that began in autumn 1923 soon led to a modification of the original plans from the summer of the same year. As a result of the increase from 458 million passengers in 1923 to 567 million in 1924, the tram needed all of its existing vehicles again, and new trams even had to be purchased at the beginning of 1924. As a result, only brand-new vehicles were considered for the light rail system anyway, including for Sunday and public holiday traffic. The homogeneity of the entire fleet of light rail vehicles was a great advantage.

In this context, the municipality of Vienna opted for more motorized vehicles in order to be able to reach a maximum speed of 40 km / h. This decision in turn entailed the conversion of the signal systems and security technology as well as an independent power supply. The voltage chosen for the tram was now 750 volts direct current, unlike the city network. Thanks to the new acquisition, it was possible to construct modern railcars capable of multiple traction and equipped with a contactor control. This made significantly longer trains possible than was common in tram traffic at the time.

The new vehicles should still be able to be used in the tram network. By procuring universally usable trams, the tram management wanted to enable so-called transition lines between its two parts of the company and to prevent two thirds of the trams from being out of use for 345 to 355 days a year. The idea at the time was to use only 60 of the 150 railcars that were newly purchased on the occasion of the commissioning of the Stadtbahn, the remaining 90 in the tram network during the week and only on the tram on a few hot summer days. At the same time, it was planned to convert 128 old, small tram cars into sidecars. This would have been possible because the new, large and heavy railcars could pull two large sidecars and the associated increase in capacity would have led to a reduced need for personnel and thus to significant savings. In fact, the total number of railcars in 1925 would only have increased by 22 units. However, the Viennese were disappointed with the appearance of the first light rail vehicles , because the light rail vehicles - instead of the four-axle bogie cars that were generally expected - were only given two-axle vehicles because they could be used in the tram network.

In the end, this reciprocal use never came about, but the municipality of Vienna used some cars that were not needed on the Stadtbahn from 1926 in pure tram traffic.

Contract conclusion and exit clause

It was only after lengthy negotiations that began on October 22, 1923 that Mayor Reumann's successor, Karl Seitz , who had only been in office since November 13, 1923, succeeded in concluding the agreement with the state railway on December 1, 1923. However, due to the political developments after the First World War, the owner of the Stadtbahn was unable to make decisions. As an alternative, the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB) - which has since emerged from the kk Staatsbahnen - received the authorization to conclude a contract with the municipality of Vienna. This was regulated by Federal Law Gazette number 20 of January 11, 1924, which came into force retrospectively on December 21, 1923. According to a contract signed on March 12 and 13, 1924, the municipality of Vienna finally leased the five routes mentioned above. It had already been agreed beforehand that "the small railroad operation will only run for a period of 30 years and that there is the option of eliminating it by terminating the user agreement in the event of unforeseen developments in traffic conditions".

In particular, a clause was agreed in 1923 that authorized the Austrian Federal Railways to terminate the contract with the municipality of Vienna after ten years if the urban railway lines were required to set up an electric full-line railway. The view expressed in various publications that, due to the ten-year term of the contract, that only trams were procured for the Stadtbahn in 1925, turned out to be wrong. On the contrary, precisely because of the fact that the tram operation is only regarded as a temporary measure, this early termination option was provided for in the contract.

The creators of the Viennese electric light rail, in addition to tram director Spängler, former mayor Reumann and mayor Seitz, vice mayor and city councilor Georg Emmerling - who was then the top head of Vienna's transport system - and city councilor Hugo Breitner .

The electrification of the light rail system was of great importance for the municipal administration. The Viennese Social Democrats had the graphic artist Victor Theodor Slama draft a special election poster for the combined national and local council elections on October 21, 1923 , even during the negotiations to take over the same . It shows, next to a worker and community buildings, a three-car train of the electric light rail and gave the party a resounding success in the election.

Handover of the infrastructure

The individual sections of the light rail network could only be handed over to the municipality of Vienna a few months after the contract was signed, and only in stages, whereby the municipality ordered its first new light rail vehicles in February 1924. It all began on April 18 and 25, 1924, with the belt line from Michelbeuern to Heiligenstadt, the Danube Canal line, the connecting arch and the Lower Wiental line, the Heiligenstadt and Hauptzollamt stations only after the state railway had converted the tracks. On October 6th and 8th 1924 the belt line from Michelbeuern to Meidling-Hauptstraße and the Upper Wientallinie finally came to the municipality of Vienna. This bisection of the belt line had become necessary because the state railway maintained the steam-powered transfer traffic between Hütteldorf-Hacking and Alser Straße until the end of the summer timetable on September 30, 1924. Tram director Spängler even mentions October 10, 1924 as the final handover date for the systems.

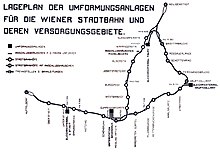

Start of renovation work

Ultimately, the electrification works began on May 26, 1924 in Heiligenstadt, a siding was already on 27 May 1924 in Michelbeuern between the route of the tram line 8 and the track 2 of the freight train station in operation while the trains of the Federal Railways continue the track 1 as headshunt up was available for a provisional track termination at line kilometer 5.2. It was not until September 12, 1924, that construction work could then also be carried out from Hütteldorf-Hacking. The construction trains , which performed all auxiliary services such as material transport and overhead line installation, consisted primarily of vehicles from the former Vienna Steam Tramway . These included the box locomotives 5, 12, 13, 15, 18 and 22, the steam tramway sidecars 5, 9, 25, 31, 57, 61, 73, 75, 77, 79, 81 and 98 with working platforms on the roofs, supplemented by Freight wagons of the steam tramway as well as the tram. The wagons with building materials arriving from the state railway were transferred to the main customs office until the points connection there was removed. The electrification work was divided into several construction lots and was carried out by the companies AEG , ELIN , the Austrian Brown, Boveri Werken (BBC) and the Austrian Siemens-Schuckertwerke (ÖSSW).

Ultimately, only a comparatively short construction period was available because electrical operations between Hütteldorf-Hacking and Michelbeuern were to start at the beginning of the excursion season or in the summer of 1925, in accordance with an agreement with the Austrian Federal Railways. According to another source, May 1, 1925 was planned to be the restart date in January 1925.

Apart from the electrification, the station buildings, the staircases and the platforms had to undergo a thorough overhaul before being put back into operation. It was also necessary to replace a large number of sleepers and remove rust from the bridge structures and partially repaint them.

After the Arlbergbahn in 1923 and the Salzkammergutbahn in 1924, the Vienna Stadtbahn was only the third Austrian railway line to be electrified after the First World War. In 1919, the Peggau – Übelbach local railway went into operation and was electrified from the start.

Separation from the rest of the railway network

The lease agreement between the Austrian Federal Railways and the municipality of Vienna led to a whole series of other renovation and adaptation work in addition to the electrification. The city administration separated the light rail at the main customs office, Heiligenstadt and Hütteldorf-Hacking junction stations from the rest of the Austrian railway network and, in return, linked it to the tram network at Gumpendorfer Strasse and in Michelbeuern. The electric light rail was henceforth a so-called island operation in the railway network. The three new access points were created, Main Customs Office WESt., Heiligenstadt WESt. and Hütteldorf-Hacking WESt. From an operational point of view, from 1925 onwards, there was one touch station and two connecting stations .

In addition, the routes after electrification were a little shorter. The Obere Wientallinie in Hütteldorf-Hacking no longer began at kilometer 0.000, but only at kilometer 0.075, based on the center of the loop. The new terminus in Heiligenstadt was on the belt line, again based on the middle of the loop, now at kilometer 8.317 instead of the previous kilometer 8.407. The Danube Canal line was even shortened by 328 meters because it now joins the belt line in front of the Heiligenstadt train station.

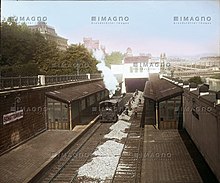

At the two end stations, the tram company had two new separate reception buildings , two new operations buildings and new platforms built especially for the electric light rail . In view of the not yet foreseeable useful life at the time, the latter only received a simple wooden roof.

Legal status from 1925

Despite its separation from the national rail network and the express tram service with direct wagon transfer from and to the tram network , the electric light rail initially remained a railway even after 1925. As such, their routes continued to be listed in the official timetable , for example . There the Untere Wientallinie, the Donaukanallinie and the connecting arch were to be found under the table number 1, while the belt line was assigned the number 11. The Upper Wientallinie, in turn, was listed under both numbers.

With the municipalization , the distinction between carriage classes was no longer necessary ; the second or third class was replaced by an unspecified unit class analogous to the tram. De facto, the wooden seating in the new coaches corresponded to third class in terms of comfort on the railroad, while the so-called upholstered class was completely eliminated. In addition, initially not all of the cars on the electric light rail were heated, only the railcars, but not the sidecars. Only in later years did the sidecars also have two fresh-flow radiators each.

In 1925, smoking trolleys were also significantly reduced. While smoking was still allowed in eight out of ten cars on the steam light rail, on the electric light rail only the second and penultimate car of a two-axle train, and in the case of three-car trains, only the middle car were designated as smoking cars. They were labeled flexibly using black and white boards in the format of a train route sign, which were hung in the corresponding brackets instead. In contrast, the non-smoking cars were not explicitly signposted.

With electrification, the transportation of checked baggage in special baggage compartments ended , and with the no longer practiced transition to the local lines of the state railway, the electric light rail trains no longer required on- board toilets . Corresponding to the conception of a tram, the new railcars only had the usual foot-operated warning bell for issuing warning signals . A compressed air whistle was not provided , despite the presence of compressed air . The triple headlights that already existed on the steam light rail system were also omitted in favor of a simple, centrally located headlight . An additional light source resulted from the illuminated line signal display on the roof. It was similar with the train end signal . Instead of the three red lanterns customary on the steam light rail, the electric light rail only had one red roof signal disc until 1946/1947. After that, the red end disk was attached to the headlight because of the complex manipulation when turning in stick tracks .

New turning systems

Although the electric light rail vehicles were also bidirectional , reversing loops were created in Heiligenstadt and Hütteldorf-Hacking to simplify operations . They are based on the original plans for the use of three-car tram trains, which would have run at a much more frequent pace than the electric light rail trains ultimately used with up to nine cars. Both loops had an overtaking track and were driven through in a clockwise direction and thus without a track crossing ; due to the separate platforms, this was done without passengers. Because all four platforms in the two named end stations were in the straight track area, relatively long distances had to be covered on the way to and from the street as well as the transition from and to the state railway trains. In contrast to the rest of the route network, there were grooved rails instead of Vignol rails in the loops , and a different maximum speed of only 15 km / h applied there.

Otherwise, the light rail trains turned everywhere by changing the direction of travel . In Hietzing , a new turning system went into operation in 1925, from then on - according to actual demand - not all trains had to be forced to and from Hütteldorf-Hacking.

Adaptation of the track position in the stations to the narrower vehicles

Because the car bodies of the new electric light rail cars - analogous to the much narrower clearance profile in the tram network - were only 2240 millimeters wide, and thus 910 millimeters narrower than the 3150 millimeter passenger cars of the steam light rail , the tracks in the stations had to be 450 millimeters closer to the Platform edges are moved. The distance to the center of the track was reduced from the original 1650 millimeters to just 1200 millimeters.

The smaller width of the new vehicles also had a significant impact on the ratio between sitting and standing . For example, the seat divider on the steam light rail was still 2 + 2 in the second and 3 + 2 in the third class, while the electric light rail only had a 2 + 1 division. This means that instead of the previous 36 in the second and 44 in the third class, only 24 seats were available per car. This was compensated by the larger standing capacity of the platforms. In the event of overcrowding, up to 99 people could be transported per car, while the steam light railroad had a maximum of 91.

Furthermore, the electric light rail got by without the transfer points for construction trains , which were set up in certain stops on the steam light rail . They were removed in the course of the renovation work.

Reduction of the platform height

Simultaneously with the approach of the platforms, the tracks in the course of electrification by 15 and 16 centimeters were aufgeschottert their new height was thus only 35, respectively 34 cm above rail level . These measures reduced the maximum usable length of the platforms from 120 to 115 meters. Since both the locomotive and the two luggage compartments at the ends of the train were omitted with the electric light rail in comparison to the steam light rail, this did not affect the capacity. A train of the old light rail system consisted of a maximum of eight full and two half two-axle passenger cars, while a train of the new light rail system had a maximum of nine two-axle cars.

Above all, the gravel prevented the lowest step of the car from being lower than the platform. This, in turn, was indispensable for operation in the street, where access was sometimes made directly from the lane. Ultimately, the difference in height between the platform and the lowest step of the car was roughly the same as in the case of the steam light rail, but passengers then only had to climb one - instead of the previous three - steps to reach the 745 millimeter high boarding platform. In the car itself, there was another step, 200 millimeters high, to be negotiated between the platform and the passenger compartment.

The new boarding conditions had a positive effect on the passenger switching times in the stations, especially since there was initially a special passenger flow control for the 1.2 meter wide door openings . According to this, the travelers were originally required to enter the car via the outside of the platform, while those getting off should leave the car via the respective inside of the platform - i.e. the area directly adjacent to the passenger compartment - so as not to obstruct each other. At the time, this directional regulation was also common for many types of trams in Vienna, but in the long term it did not establish itself in Vienna either on light rail vehicles or on trams. In return, passengers on the electric light rail could no longer distribute themselves as evenly over the entire train as with the steam light rail due to the lack of intercar crossings.

The separation stations of Meidling-Hauptstrasse and Brigittabrücke / Friedensbrücke were also the only stations that had central platforms instead of outer platforms due to their transfer function . In this case, passengers also got on and off on the right hand side.

Adaptation of the track system for operation with tram cars

Simultaneously with the electrification, the tram management changed the guide and groove widths of the focal areas of points and crossings as well as the control arms to tram dimensions with smaller groove widths, adapted to the larger distance between the rear surfaces of the tram wheel sets . These dimensions were also retained in the later subway construction. They are the reason why the underground railcars cannot be continuously transferred to the main workshop on their own axles via the railway network.

The electric light rail vehicles themselves also had to be specially equipped for mixed traffic. Because they were operated on the Vignole rails with the S 33 profile and deep-groove frogs taken over from the steam light railway, they ran on special wheel tires with 100 millimeter wide treads. The wheel flanges were made weaker than on normal full-rail cars, but stronger and higher than on normal tram cars.

In 1924/1925, only minor changes and replacements of individual parts were necessary on the tracks themselves. Guard rails have been provided in narrower arches, usually less than 150 meters in radius, for safety reasons .

New staff

In parallel with the electrification work, the tram company had to hire numerous new employees. In the course of 1925, the workforce grew from 15,483 to 16,306, which means that 823 new employees were added due to the tram. In 1927 the entire workforce for the traffic, rail maintenance and workshop service of the electric light rail, excluding the officials in the central administration and excluding the employees in the converter works, was then around 1200 men.

In order to save personnel compared to the previous steam operation, the cash register and barrier systems at the less frequented stops were modified accordingly. So the so-called barrier guards took over the ticket issue themselves, while counters were still available everywhere on the steam light rail .

The elimination of the heater meant that the electric light rail trains were now only manned by two instead of three railway workers. New was also that the train driver the train driver , then traditional in Vienna Motor leaders named as train attendants supported. That means he drove as a companion - to the left of the driver - in the front of the driver's cab . In addition to dispatching trains in the stations, he was responsible for signal monitoring and official monitoring of the driver. However, all other cars were unoccupied, and the passengers were responsible for opening and closing the car doors. Unlike the earlier wagons of the steam light rail, emergency brakes were available to them in emergencies .

Another innovation compared to the steam light rail system was the delayed start of operations on May 1st , with the railcars being decorated with flower garlands for the rest of the day . This practice, which had existed with the tram since 1913, also made it possible for the tram personnel to take part in the May march .

Test drives

Although the mild winter of 1924/1925 favored the conversion work, the electric tram could not go into operation on May Day 1925 due to the late handover of the infrastructure by the state railway. Only on April 9, 1925 was the first test run with an electric light rail train between Michelbeuern and Meidling-Hauptstrasse. The training of the driving staff began soon afterwards and lasted a total of six weeks.

In order to be able to gather experience with the technologies newly introduced for the light rail system in advance, the main workshop adapted six conventional tram cars provisionally for light rail operations as early as September 1924. The railcars 2414 and 2530 as well as the trailer cars 3751–3754 received Knorr compressed air brakes at that time, the railcars also received pantographs. In this condition, the vehicles then carried out tests on line 80, and in January 1925 the railcars were also fitted with a driving block. With the delivery of the first light rail cars, the test cars could finally be restored to their regular streetcar condition in March 1925.

Grand opening

The grand opening of the Vienna Electric Light Railroad took place on June 3rd at 11:00 a.m. at the Alser Strasse station when Vice Mayor Georg Emmerling asked Mayor Karl Seitz to give the order to open the new operation. In the presence of Federal President Michael Hainisch , a few ministers, numerous MPs, the other city fathers and thousands of citizens, he gave the following speech before he sent the first two special trains to Hütteldorf-Hacking:

“The jubilation over the opening of the tram couldn't be too stormy, because we already know the bad lines well enough. Thirty years ago, the Stadtbahn was built in the way that we now have to continue it, based on military considerations; at that time, little consideration was given to the needs of the city of Vienna. We would like to give Vienna good traffic, but we don't have the money and we are forbidden to borrow it. I have to admit with sadness that the commissioning of the entire tram will not provide us with ideal traffic. What we need, what Vienna needs for its development, is the subway that leads from the heart of the city out into the open, where the working people live. At this moment, as Mayor of the City of Vienna, I vow, and the whole town council, with me, that it will and must be our greatest endeavor to make the underground railway possible. Let us now rejoice that part of the electrification work has been completed. I hereby declare the Alserstraße – Hütteldorf route open. "

A total of three seven-car trains were involved in the opening.

Start of regular operations

The scheduled service of the Vienna Electric Light Rail began in the early morning hours of June 4, 1925 on the Michelbeuern – Hütteldorf-Hacking route. In contrast to the previous steam light rail system, it ran in a fixed cycle schedule that was in effect for the entire operating time. From now on there were de facto two light rail vehicles in Vienna, because the suburban line ran as a steam light rail until 1932. For electric light rail competent railway companies , with the legal status of a private company , was henceforth the city of Vienna - urban trams .

Next, on July 22nd, 1925, the northern belt line between Michelbeuern and Heiligenstadt was put back into operation; this expansion took place in the early hours of the morning without any celebration. At the same time as the extension to Heiligenstadt, the car hall there went into operation. From now on, the two deployment locations each shared half the car exit. The trains passed through the Michelbeuern freight station without stopping. The third reactivated section was the Untere Wientallinie on September 7, 1925, which again went into operation in the early hours of the morning without an opening ceremony.

After the Danube Canal line including the connecting bend and the Gumpendorfer Strasse junction were completed, the electric light rail went into full operation in October 1925. For this purpose, a second opening ceremony, including subsequent special trips, took place at the Brigittabrücke station at lunchtime on October 19, 1925. Federal President Michael Hainisch also took part again, as did Justice Minister and Vice Chancellor Dr. Leopold Waber . Scheduled operation on the entire network finally began in the early morning hours of October 20, 1925.

In the final stage, the new means of transport consisted of a 25.559 kilometer long and continuous double-track network, plus 0.892 kilometers of connecting tracks to the tram network. It originally had 26 stations, including five passenger stations , a freight station and 20 stops . The distance between two passenger traffic stations varied between a minimum of 600 meters in the Schottenring – Roßauer Lände section and a maximum of 2,400 meters in the Brigittabrücke – Heiligenstadt section. The mean distance was around 850 meters.

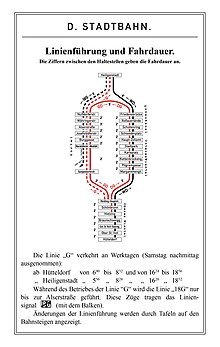

Special case line 18G

A special case in the light rail network, but also in the tram network, was the so-called tram looping line 18G , which also went into operation when full operation began on October 20, 1925. Coming from the direction of Heiligenstadt, it switched to the tram network shortly before the Gumpendorfer Strasse station at the junction there, in order to then follow the course of tram line 18. A whole series of legal and operational peculiarities had to be taken into account for this mixed operation . These resulted on the one hand from the various regulations for trams and railways, and on the other from local customs. These included, for example, escorting with conductors - only in sections - the different voltage , the track width deviating by five millimeters , the maximum train length, the various pantograph systems, the regulations regarding seated or standing railcar drivers and closed or open doors and the requirement to use the grass collector to lock on the light rail routes.

Interwar period

Success through community tariff with the tram and higher travel speed

The joint tariff for the tram, which was introduced with the start of full operation on October 20, 1925, made the new mode of transport really popular and carried over 90 million passengers in its first full business year in 1926. From the beginning of September 1926, the electric light rail also carried dogs, while the tram service only existed from 1931. These were only allowed to be taken on the front platform of the smoking trolleys and only outside of the working day rush hour, the fare corresponded to that of an adult. Before that, the steam light rail had already carried dogs.

In addition, despite its lower top speed of only 40 instead of 50 km / h for the steam light rail, the electric light rail was slightly faster than its predecessor due to its better acceleration and braking deceleration . In 1925 the average cruising speed was 23 and 23.5 km / h, respectively, while the steam trains only reached 20 to 21 km / h. Another source from 1928 gives an average of 24 km / h for the electric light rail, assuming a starting acceleration of 0.5 seconds per meter, a braking deceleration of 0.7 seconds per meter, 20 seconds station stop and 38 km / h top speed , for 1962 24.3 km / h are given. However, the steam light rail had previously stayed at a station of only 15 seconds, albeit with significantly lower passenger numbers. Tram director Spängler emphasized on the occasion of the opening of the electric light rail that it was only slightly slower than the light rail vehicles in Berlin , Hamburg and Paris , which at that time only achieved average speeds of between 24 and a maximum of 28 km / h.

In any case, the electric light rail was always significantly faster than the Viennese tram. In 1925 it had an average cruising speed of only 12.5 km / h, which could only be increased slightly to 14.2 km / h by 1962.

The contemporary poem To Remember the Electrification of the Vienna City Railroad by Joh.Maierbichler described the progress made by the new means of transport at the time as follows:

“The electric train

is a beautiful invention.

We also owe it to

the fast connection.

Now you can

no longer suffocate from the smoke ,

And you stay on the seat

No longer pecking in

the soot. Splendid in amazement,

The tram leads us,

As

fast as it flies, You drive there as if smeared.

The Opponitz waterworks

give us more light and power,

the light rail is electrified

Isn't that a splendor?

For greater convenience

for the traveler now,

you change from the light rail

to the tram.

Each honor her work

What she accomplished in a moment,

Now the city of Vienna has

awakened to new life. "

Abandonment of Freight Transport (1927)

Initially, the Vienna Electric Light Rail also carried out freight transport . Since most of the goods customers of the steam light railroad were on the non-communalized suburb line, the municipality of Vienna was only responsible for the delivery of the freight station with integrated market hall in Michelbeuern from 1925 onwards . This was somewhat dismantled in the course of electrification. Instead of originally several freight tracks connected on both sides, only one was available, which could only be reached from the direction of Heiligenstadt without changing the direction of travel. This siding led to a magazine and a loading ramp . The transport of goods only played a subordinate role. In 1926, for example, the electric light rail only carried 8,136 tonnes of freight, while the tram still carried 52,741 tonnes. When the municipality of Vienna therefore needed the site of the freight station in Michelbeuern for the third depot of the Stadtbahn in 1927, market traffic also ended.

Travel time reduction

Around 1930, the municipality of Vienna succeeded in speeding up the electric light rail on seven sections:

| Kettenbrückengasse <> Karlsplatz : | from three to two and a half minutes |

| City park <> main customs office: | from two to one and a half minutes |

| Schottenring <> Roßauer Lände : | from two to one and a half minutes |

| Roßauer Lände <> Friedensbrücke : | from two to one and a half minutes |

| Friedensbrücke <> Heiligenstadt: | from six to five minutes |

| Friedensbrücke <> Währinger Strasse : | from five to four minutes |

| Währinger Strasse <> Heiligenstadt: | from five to four minutes |

This reduced travel times on the DG / GD and WD lines by three minutes per direction and on the G and 18G lines by one minute per direction. As a special feature, the operator officially announced half-minute departure times for the stations at Karlsplatz, Stadtpark and Roßauer Lände. When it reopened after the Second World War, travel times were extended to the 1925 level, making half a minute of departure a thing of the past. There was essentially no change in this timetable until the changeover to subway operation or the introduction of modern articulated multiple units on the belt line in the 1970s and 1980s. Only the sections Friedensbrücke - Heiligenstadt and Währinger Straße - Heiligenstadt, which only reopened in 1954, retained their shortened travel times from the interwar period even after the Second World War.

Dissolution of the Commission for Transport Systems in Vienna (1934)

On July 1, 1934, after the early termination of the 1924 lease and liquidation of the Vienna Transport Commission, which was founded in 1892, the infrastructure of the electric tram finally became the property of the municipality of Vienna, while the state railway then took over the suburban line and the remaining vehicle material of the steam light rail took over. A possible return of the inner-city routes to the Austrian Federal Railways was no longer necessary and the municipality of Vienna gained the necessary planning security. In 1925, however, the dissolution of the commission failed because the federal government demanded that the municipality of Vienna should also electrify the Hütteldorf-Hacking-Purkersdorf and Heiligenstadt-Kritzendorf lines and include them in their new light rail system. According to the new concession, the electric light rail was henceforth only a small train for passenger traffic. This also meant that the license to transport goods - which had not been used by the municipality of Vienna since 1927 - expired.

“Anschluss” of Austria and World War II

Recession to the tram (1938)

After the " Anschluss " to the German Reich in March 1938, the ordinance introducing imperial regulations on trams in Austria of June 29, 1938, brought the tram construction and operating regulations (BOStrab) into effect from July 1, 1938 set (Reichsgesetzblatt I No. 100 of June 29, 1938, p. 705). At the same time, the existing regulations for small railways in Austria were also replaced; the regulations that had previously existed for them were replaced by the regulation on the construction and operation of small railways and the railways of 7 July 1942 (Reichsgesetzblatt II, No. 24 of 24 July 1942, p. 289) finally repealed. In the course of this change in law, the German Reich Ministry of Transport also classified the Viennese electric light rail as a “tram” in 1938 . A direct consequence of this was that her timetable was no longer listed in the official timetable. For example, it is no longer included in the 1939 summer course book valid from May 15.

The German BOStrab was in force in Austria for almost 20 years until it was suspended by Section 58 No. 32 of the Railway Act of 1957 (EisbG, Federal Law Gazette No. 17/1957, p. 467) announced on March 7, 1957 . It was followed by the ordinance of the Federal Ministry of Transport and Electricity from September 2, 1957 on trams (1957 Tram Ordinance ) (StrabVO, Federal Law Gazette 62/1957 of October 2 ) on the basis of Sections 19 (4), 21 and 23 of the Railway Act 1957, p. 1095), which was based largely on the BOStrab.

In turn, the 1957 Tram Ordinance , which has since been amended several times, was completely revised in 1999 and is now the ordinance of the Federal Minister for Science and Transport on the construction and operation of trams ( StrabVO ).

In practice, the re-concession to the tram had no consequences for the operation of the light rail. Above all, in 1938, like other railway lines in the now called Ostmark country, it was not converted to the right-hand traffic that would henceforth be used in road and tram traffic, but remained left-hand traffic. This was possible without any problems, as the entire tram ran on its own track, so there was no need for a changeover.

Introduction of stationary train dispatchers (1943)

In order to speed up the handling of light rail trains, the Vienna Transport Company introduced stationary train handlers on every platform on January 18, 1943, also known as platform handlers, platform conductors or colloquially known as "pillar whisperers". They had the latter nickname because they had to step up to certain pillars of the platform canopy to dispatch a train, which were located in the rear third of the platform and were marked with a white, green and white ring. There was one each microphone for announcements via loudspeaker system installed.

First restrictions due to the war

During the Second World War , the light rail fleet in particular was heavily used. In order to better distribute the passengers to the individual wagons, the smoking ban was introduced as early as April 17, 1944 , while the general smoking ban on all means of transport operated by the Vienna public transport company did not apply until October 25, 1948. From the summer of 1944 onwards, the air raids that began at that time severely affected the vehicles and the structures. In the following four periods of time, the tram network could only be used in partial sections, with trains without a line signal disc again running from January 1945 - for the first time since the opening year:

- July 16, 1944 to August 15, 1944

- September 11, 1944 to September 22, 1944

- October 18, 1944 to December 29, 1944

- January 15, 1945 to February 4, 1945

From February 18, 1945, operations were restricted again, and on February 19, line 18G ran for the last time.

Complete recruitment in 1945

From February 22, 1945 to February 26, 1945, electric light rail traffic had to be completely stopped - for the first time in its history. In the final phase of the war, the northern sections of the belt line as well as the Danube Canal line and in particular the Heiligenstadt train station were badly damaged by the heavy air raid on March 12, 1945 , after which the light rail traffic was completely damaged for the second time from March 13, 1945 to April 4, 1945 rested. After the bombardment stopped at the end of March 1945, restoration began immediately. As a result, the WD line was able to start an island operation between Meidling-Hauptstrasse and the main customs office on April 5, 1945 with the trains that had stopped on the route, although the Red Army was already at the city limits. But the very next day, April 6, 1945, the artillery fire and the approaching fighting required the third complete shutdown of the light rail. The tram had previously ceased operations on April 1, 1945.

A total of eight iron bridges and ten iron roofs were completely destroyed by the war, nine more bridges and six more roofings as well as around 2,500 square meters of reinforced concrete roofing were partly badly damaged. In addition, the Hietzing court pavilion, once built for Emperor Franz Joseph I , lost its direct access to the platforms during the war.

Post-war period and first rationalization measures

reconstruction

While the first tram passed through occupied Vienna on April 28, 1945 , repair work on the light rail system only began at the end of April 1945. Before operations resumed, temporary iron auxiliary bridges had to be installed in four of the connecting arches and in one of the Alser Strasse station's vaults. They could only be dispensed with after the final repair of the relevant viaduct arches. In addition, the damaged iron concrete roofing of the Danube Canal line had to be makeshiftly pinned in five places and 1.2 kilometers of rails replaced. So operations could only be resumed as follows, with certain stations receiving severe damage from bombs and therefore initially having to be driven through without stopping:

| May 27, 1945: | Hietzing - Meidling-Hauptstrasse - main customs office | initially without stopping at Schönbrunn |

| June 27, 1945: | Hütteldorf-Hacking - Hietzing | initially without stopping in Unter St. Veit-Baumgarten and Braunschweiggasse |

| July 18, 1945: | Main customs office - Friedensbrücke - Nussdorfer Straße junction - Michelbeuern | |

| July 30, 1945: | Michelbeuern - Meidling main street | initially without stopping in Alser Strasse and Josefstädter Strasse |

| August 30, 1945: | Schönbrunn | |

| November 19, 1945: | Connecting tracks to the tram network on Gumpendorfer Straße | |

| November 21, 1945: | Josefstädter Strasse | |

| November 30, 1945: | Alser Strasse | |

| February 14, 1947: | Under St. Veit-Baumgarten , direction Meidling-Hauptstraße | |

| March 4, 1947: | Under St. Veit-Baumgarten, direction Hütteldorf-Hacking | |

| November 28, 1948: | Braunschweiggasse | |

| September 18, 1954: | Friedensbrücke - Heiligenstadt and junction Nussdorfer Straße - Heiligenstadt |

The mixed service line 18G no longer went into operation after the Second World War, its restored track connection on Gumpendorfer Strasse served only as an operating line from then on and ultimately ceased to exist with the abandonment of the Gumpendorfer Strasse signal box on August 2, 1965. As a further consequence of the war, the heating systems in the majority of the light rail vehicles were no longer operational and were no longer repaired.

On November 26, 1945, the Wiener Verkehrsbetriebe introduced the passenger flow principle on the Stadtbahn, known in Vienna as flow traffic . Passengers should only get into the car at the back and only get off at the front so as not to interfere with each other. But although the train dispatchers on the platforms pointed out the flow of traffic to the passengers via loudspeakers, nobody saw the purpose of this measure. The operator had to admit the failure of this attempt after just a few weeks.

As the first major modernization measure after the Second World War, the Mariahilfer Straße-Westbahnhof tram stop was completely covered and new underground entrances in 1951 in connection with the new construction of the neighboring terminus station . It was the first completely underground station in Vienna at all, a construction method that was not yet possible with the earlier steam light rail due to the smoke development. The second underground station of the electric light rail was finally the main customs office from 1961.

A special operational situation arose in 1951 when work was done on the lining wall between the Margaretengürtel and Pilgramgasse stations, as a result of which a track had to be temporarily laid there .

Because of the destroyed bridges, trains could not return to Heiligenstadt until September 18, 1954, although work on restoring the two lines leading there did not begin until 1952. Before that, the section from Nussdorfer Straße to Heiligenstadt was used in 1946 and 1947 to park damaged tram cars, including former steam tram sidecars. After almost ten years, the electric light rail was reactivated in full.

The slow delivery of the new sets acquired after the Second World War led from July 3, 1957, on all four lines to an interval extension of eight to ten minutes during rush hour. That means, there was now a uniform rhythm throughout the day, only in the evening the tram only ran every seven and a half minutes. Alternatively, four push-in trains ran from then on in the morning , but each made only one trip. This timetable restriction, which was announced temporarily at the time, was not revised even after the second generation of vehicles had been fully commissioned.

Introduction of automatic doors and door closing signals (1954)

With the conversion to the second generation of vehicles, which began in 1954, from 1961 only vehicles with automatic doors were in use. As a result, the previously very high number of accidents fell dramatically. As early as 1965, according to the accident statistics of the public transport company, the light rail was the safest means of public transport in Vienna, and that year there were only three accidents. The folding doors on the new cars were closed pneumatically by the driver, who had a swivel switch at his disposal. Before departure, the train dispatchers also had to operate a key switch for the then newly introduced door closing signal to the driver, which was attached above the exit signal . It had two positions, with a white vertical bar for "close doors" and a red horizontal bar for "reopen doors".

Modernization backlog in the first half of the 1960s

In 1959, the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB) opened the Vienna S-Bahn , at the time still called Schnellbahn . From March 27, 1961, there was a collective bargaining agreement between this and the means of transport of Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe. The Schnellbahn initially operated with steam locomotives, before the ultra-modern electric multiple units of the 4030 series took over operation in 1962 . In contrast, the light rail system was already considered technically obsolete back then. In particular, the low top speed of 40 km / h and the operation of long two-axle trains with no passage and with steps for getting in and out of the train have long been an anachronism . Only the inner-city routes, which were completely separated from individual traffic, were contemporary. Previously, the Alwegbahn plans pursued from 1957 to 1962 prevented any further development and modernization of the light rail. At times it was even planned to tear off the belt line and replace it with the Alwegbahn.

From 1963, the municipality of Vienna primarily focused on building the Vienna underground tram , both of which went into operation in 1966 and 1969. In both cases, these were routes that were already included in the urban railway planning at the end of the 19th century. A connection between the belt line and the underground tram tunnel on the southern belt between Eichenstrasse and Südtiroler Platz was planned at times, but was not implemented.

In exactly the opposite direction to the developments in the early 1920s, the State Railways offered the City of Vienna the repurchase of the Stadtbahn in 1964 in order to integrate it into their new rapid transit system. As early as 1955, a commission at the 1st Vienna Road Traffic Challenge recommended that the inclusion of light rail lines in the future rapid transit network should also be investigated in order to improve traffic conditions. But although a broad coalition of the Austrian Federal Railways, Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe, the Social Democratic Party of Austria , the Austrian Trade Union Confederation , the Chamber of Labor and almost all newspapers supported the project, the Vienna City Council rejected it. In return, he decided on January 26, 1968 to include at least the Wiental line and the Danube Canal line of the Stadtbahn in the basic underground network that was built up from 1969 and to modernize them comprehensively in this context.

Safety driving circuits and track magnets (1965)

In a further rationalization step, the light rail railcars were equipped with dead man's devices in the form of safety driving circuits (Sifa) by August 16, 1965 , which automatically stopped the train if the driver could no longer react. The associated impulse pedal had to be lifted when the horn sounded and then pressed again; this also applied when the train came to a standstill. If this was not done, automatic braking and disconnection of the traction current took place after four seconds due to a voltage drop in the control current contactor .

The modifications in 1965 made the second-generation railcars even more complicated. This made them even more prone to failure, at times there were difficulties in being able to provide enough vehicles for the run.

In parallel with the introduction of the safety driving system, the mechanical travel locks used since electrification were replaced by a wear-free, point-like, magnetic train control system. Only when the signal was green was the permanent magnet made ineffective by counter-excitation and the train could pass. If, on the other hand, the signal showed red, the magnet was effective and the train received an emergency brake as it passed. This was also indicated to the driver by a red control lamp that could only be deleted with the Expeditor key. If the train had to deliberately run over a signal, the release button had to be pressed, which temporarily bypassed the safety driving circuit. As a result, the red signal in light rail operations, which was regarded as indispensable for the railways, was repeatedly watered down and often run over without a care. Since full braking was necessary for defective signals, this signal system was often very cumbersome in operational terms.

Elimination of the assistant in the driver's cab and the platform handler (1965)

With the introduction of the safety driving circuit, also from August 15, 1965, there was also no need for the driver to be present in the driver's cab. Instead, from now on, the previous assistant supervised the handling of the trains as a train driver from the second railcar and arranged for the doors to be closed from there alone. Here he announced the imminent departure over the platform loudspeaker, the clearance was carried out using the existing door closing signals and acoustically by means of a bell signal, which had to be repeated after the start for safety. In contrast to the former locomotive attendants, from 1965 the train drivers also no longer had to be trained train drivers, which saved training costs. From this point on, women were also permitted as train drivers.

In 1965, through the train driver clearance, a large part of the 90 platform handlers at that time could be saved, whereby the designation "column whisperer" passed from these to the train drivers. Only in a few stations, including Meidling-Hauptstrasse in the direction of Heiligenstadt, were additional platform handlers active during rush hour traffic.

A further rationalization measure of the 1960s was the abolition of the barrier guards in the stations, with which another relic from steam light rail times disappeared. They were from 11 January 1967, first in Meidling Main Street, Palace and Hietzing by AEG - canceling replaced before until 21 December 1968 all access points could be equipped.

Conversion to subway operation (1968–1989)

Preparation of the underground trial operation (1968)

In 1968, the year the decision was made to build the Vienna subway, the Friedensbrücke – Heiligenstadt light rail line was selected for the trial operation of the new type “U” subway cars . The renovation work began in November 1968 in Heiligenstadt, where parking and turning tracks as well as a maintenance hall were built for the test trains. The latter was completed in 1970 and was dismantled again between 1974 and 1977 after the Wasserleitungswiese depot was built .

From the summer of 1969, the embankment between the two stations mentioned, which had a cubature of 70,000 cubic meters, was removed. This was necessary in order to later be able to connect the Wasserleitungswiese depot at the same level to the Danube Canal line. From now on, the new route was one to two meters below the tracks of the neighboring Franz-Josefs-Bahn, which is why an additional 700-meter-long retaining wall had to be built. In return, the ramp lane had to be interrupted, and in its place the Franz-Ippisch-Steg was built for pedestrians . During the extensive earthworks there, the municipality of Vienna had to rent one of the four tracks of the Franz-Josefs-Bahn from the Austrian Federal Railways for light rail operations and adapt it accordingly.

On September 13, 1971, the Friedensbrücke turning facility was closed to the light rail system because it had to be converted for the underground test trains coming from the direction of Heiligenstadt. In this context, on December 2, 1972, the Friedensbrücke – Heiligenstadt section was converted to right-hand traffic; for the first time in its history, the Stadtbahn no longer ran everywhere on the left-hand side. This required appropriate track crossings on the light rail, the light rail trains changed their driving side shortly after the Friedensbrücke station. Coming from the belt line, another track crossing was built in front of the entrance to the Heiligenstadt station, whereupon the loop there was used by all light rail trains in a counterclockwise direction.

Trial operation of the subway started without passengers (1973)

For the parallel operation between old trams and new subway cars, which began on February 24, 1973, but which at that time did not yet carry passengers, the lower Friedensbrücke – Heiligenstadt section was temporarily equipped with both an overhead line and a lateral power rail . There were also two different signaling and safety systems: the conventional line block system for the light rail and the new linear train control system without main signals for the underground. In addition, a newly developed rail profile was used. In 1970/1971, the Xa rails previously used on the Stadtbahn were replaced in small construction sections with heavier S-48 U rails on the entire Friedensbrücke – Heiligenstadt route. The test trains initially only ran at night, and later also during the day between the regular light rail trains.

Start of the extended test run of the underground with passengers (1976)

In contrast to the new construction of the lines U1 (opened 1978) and U3 (opened 1991) as well as the complex conversion of the two-way line to the U2 (opened 1980), the adaptation of the light rail systems took place comparatively quickly. The U4 , which was officially released on May 8, 1976 for the "extended test operation with passengers", was ultimately the first Vienna underground line, from then on Vienna temporarily had three different urban rapid transit systems.

The conversion of the light rail lines to underground operation primarily required the replacement of the contact line by the conductor rail system. In addition, the tracks in the stations were moved away from the platforms and lowered by 15 centimeters, that is, to the original level from the steam city railway times. At the same time took place the increase of the old platforms from 50 to 95 centimeters above the running surface, a barrier-free to guarantee entry. The subway also took over the 115 meter standard platform length of the electric light rail.

The safety technology had to be completely replaced for standardized operation with linear train control. At the same time, the track changing operation was set up. The superstructure was partially rebuilt and upgraded for higher speeds, maintenance work was required on tunnels and bridges, and the power supply from the state network was also renewed. In the course of the construction work was switched to right-hand drive. The access points were rebuilt to varying degrees; this was particularly complex at the Landstrasse and Karlsplatz stations. Other modernization measures included the creation of additional entrances at the end of the station facing away from the reception building, the installation of lifts, the extension of the platform roofs to the full length of the station while at the same time dispensing with supports, the cladding of the walls with uniform panels in the standard design of the Vienna subway, the Installation of fall-leaf train destination displays as well as the complete replacement of ticket counters with machines.

In Heiligenstadt, the turning loop of the Stadtbahn was discontinued in May 1976, while the one in Hütteldorf-Hacking was still available until the local railroad operations there in 1981. In addition, during the renovation years, the light rail trains also had to turn at the stations Schottenring (April to August 1978) and Karlsplatz (August 1978 to October 1980) by changing the direction of travel; construction switches were required there. In order to make it as easy as possible to change at these temporary transfer points, there were temporary central platforms with a corresponding height difference. Because of the different boarding conditions, the Heiligenstadt train station received separate platform tracks for the G and U4 lines in 1976.

Decision to modernize the belt line (1977)

Even if the belt was not included in the metro core network as City of Vienna began in 1976 as a result of ausgelobten transport billion of the Federation, a large subsidy program for strengthening public transport, but to modernize. At the same time, it was already planned to link it with the new express tram line to the Erlaa and Siebenhirten districts , which went into operation in 1979 and 1980 and was initially served by tram line 64.

The renewal of the belt line began in 1977 with the construction of a second platform access at the Burggasse-Stadthalle station, which was available from February 16, 1978, and the start of construction for the new Thaliastraße station , which was given the abbreviation TH. This additional connection point to the tram could not go into operation until September 27, 1980, due to economic difficulties of the construction company originally commissioned with it.

At the waistline, the municipality of Vienna decided, also in 1977, against the conversion to busbar operation and the construction of elevated platforms. At the time of this decision, however, a later "full expansion" to the subway with busbars was still being considered, cars had to be purchased that could later have been used in tram operation - even if it never came to that.

For the third time in the history of the electric light rail, the Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe, relied on classic tram vehicles in overhead line operation, which - as was common at the time - were high-floor. The new cars ordered in 1978 were only 2305 millimeters wide and were delivered from July 1979. The new trains could also be operated in one-man operation with fully automated handling, which means that the railcar driver himself was the train driver from then on. However, during the introductory period there was also a train attendant temporarily on board the new trains. In 1983, after the last old wagons were taken out of service, the conversion to the new vehicles was completed. Their better braking properties and the end of mixed operation made it possible to increase the maximum speed on the belt line from 40 to 60 km / h from January 2, 1984, which resulted in an attractive reduction in travel time.

Subsequent decision to integrate the belt line into the subway network (1980)

By resolution of the municipal council on August 29, 1980, the decision was finally made to subsequently integrate the belt line, including the planned expansion in the south, into the subway network. The name U6 was specified because the U5 had been in the planning stage since the 1960s.

The full expansion of the line was finally shelved. The official reasons given at the time not to use heavy standard subway trains on the belt line - especially with regard to the bridge over the line and the historic city railway arches - were given weight reasons and various restrictions on the clearance profile, but financial reasons were more likely to have been decisive. Ultimately, an examination of the old steel structures carried out in 1981 showed that they were still in good condition. At that time , the natural aging process of steel was less advanced than expected, so that a durability of at least a few decades could be expected. Ultimately, the elevation of the platforms at the high stations of the belt line would have been structurally much more complex, especially since they sometimes extend to the neighboring bridges. Another problem was the strongly curved Gumpendorfer Strasse station, the platforms of which would have led to a correspondingly large gap between the central vehicle doors and the edge of the platform in the case of the subway double railcars. According to another source, the first-generation subway cars would not have been able to drive over the Otto Wagner Bridge anyway because of the incline there.

At that time, the third generation of light rail vehicles purchased from the end of the 1970s remained in service. However, the non-barrier-free entry and exit via stairs later turned out to be problematic as the number of passengers increased, because it increased passenger switching times. In addition, until the end of the day, no bicycles were allowed in the narrow light rail vehicles, while this was not a problem in the more spacious subway vehicles.

Series of accidents from 1975 to 1978

During the changeover to underground operation, a series of serious rear-end collisions occurred within three years , mainly due to the numerous temporary construction works , which led to a negative image of the light rail system and strong criticism from the population:

- On November 4, 1975, a train on the GD line rammed one of the WD lines in the Schwedenplatz station , five cars derailed and 14 passengers were injured. The cause was a defect in the signal systems and thus also the dead man's equipment in the trains.

- On March 5, 1977, trains 14 and 20 collided in the tunnel at the Margaretengürtel station and derailed. Previously, one of the drivers had overlooked a signal, 15 passengers were injured.

- A particularly serious rear-end collision occurred on the evening of September 14, 1977 between Meidling-Hauptstrasse and Margaretengürtel, in which 44 - sometimes seriously - injured people were to be complained about due to inadequate safety equipment. At that time, after the UEFA Cup game SK Rapid Wien against FK Inter Bratislava Viennese hooligans indoor lighting unscrewed in a delayed train line WD bulbs, so they stopped the whole lighting circuit of the last railcar. Then the rioters deliberately pulled the emergency brake and the set stopped a few meters before leaving a block section . As a result of the short circuit that had previously occurred , the tail light also failed. The immediately following train on the WG line received a signal from the signalman in Meidling-Hauptstraße that it was going on in the direction of Wiental, although the block section was still occupied and the signal indicated the stop. Thereupon he rammed the completely unlit train in front of him in the tunnel almost unchecked, which was also standing in an arc. As an exception, there was a distant signal for the next block signal, which still showed an indication of the journey. When the following train reached this, the engine driver believed that the train in front was already far ahead of him and accelerated again. Only at the last moment did he notice the wrecked train, and the emergency braking that was initiated immediately remained almost ineffective. In the collision, ten out of 16 cars were lifted off the track, wedged together and piled up to a meter and a half high. Four railcars and six sidecars then had to be retired as total losses. Three young men aged 16, 19 and 27 were ultimately only found guilty of vandalism , the engine driver received six months conditional imprisonment for driving faster than the permitted 15 km / h in the occupied block section. This accident was the reason to retrofit a light rail vehicle on a trial basis with train radio via pot antenna , speed monitoring and low beam headlights in the same year . The facilities proved their worth, so that from May 1978 94 of the remaining old railcars - despite their foreseeable retirement - received appropriate equipment to reassure the public, while the others were only allowed to run as guided railcars . In addition, after passing a main signal indicating a stop, only 15 km / h were possible for the following 1200 meters, the so-called "V 15" drive.

- On November 13, 1977, five passengers suffered injuries when two cars derailed at the Braunschweiggasse station.

- On November 19, 1977, a train ran into a buffer stop at the terminus in Heiligenstadt as a result of a braking error , and a woman was injured.

- On December 5, 1977, an empty train at the Hietzing station collided with a buffer stop, and light rail operations were disrupted for five hours.

- On January 5, 1978, a railcar driver in Michelbeuern disregarded a signal indicating a stop, whereupon two trains collided and two passengers were injured.

- On January 9, 1978, eight passengers were injured in a rear-end collision at the Hütteldorf-Hacking terminus.

- on August 10, 1978, just two days before the changeover to underground service, there was another rear-end collision at Schwedenplatz station, with eleven injuries.

Further modernization of the belt line in the 1980s and conversion to right-hand traffic

After the decision to integrate it into the subway network in 1980, the modernization of the belt line, which began in the late 1970s, gradually continued. In 1981 the renovation of the aging depot at Michelbeuern began and was completed in 1989. In addition, as part of its modernization, the belt line also received a new overhead line, with central masts with arms on both sides replacing the transverse yokes from the 1920s.

On September 7, 1983, construction work finally began on the extension of the Gürtel light rail to the Vienna Meidling station, with the subway station there still being called the Philadelphiabrücke until 2013. In connection with this construction work, the trains on the belt line only ran to Gumpendorfer Strasse from April 13, 1985, the subsequent ramp between the bridge over the line and the Meidling-Hauptstrasse station was demolished and rebuilt with a greater incline. Thus, the fork of the Wiental and Gürtellinie in the station Meidling-Hauptstraße, which existed until 1985, could be replaced by a parallel route of U4 and U6 at the same level in the new Längenfeldgasse station. There are track connections there despite the different contact line systems. In 1984, the preliminary planning for the U6 north to Floridsdorf began .

On October 31, 1987, the Michelbeuern General Hospital station went into operation , making regular passenger trains stopping in Michelbeuern for the first time in 89 years. As with the Thaliastraße station and later also with the Längenfeldgasse and Spittelau stations , the large station spacing of the belt line, which originated from the steam city railway era, could be significantly reduced in several cases. In contrast to the historic light rail stations, these new buildings had the reduced platform length of 115 meters from the start.

From June 25, 1988, operations on the connecting bend were initially discontinued, before operations on the belt line were also temporarily suspended from July 2, 1988. This was necessary in order to be able to switch to signal-based track-changing operations with scheduled right-hand traffic by September 5, 1988, which required the installation of several switch connections. Apart from a standardization of the underground transport system, the change was forced by the structural situation in the new Längenfeldgasse transfer station.

Development after 1989

On October 7, 1989, the Gumpendorfer Strasse – Längenfeldgasse – Philadelphiabrücke section went into operation. At the same time, without any further technical changes, the last two tram lines G and GD were renamed to U6. This temporarily served two different endpoints under the same line signal. This ended - apart from the remaining infrastructure and the vehicles that were still in use - the history of the Viennese electric light rail system after more than 64 years.

On November 8, 1991, Wiener Stadtwerke - Verkehrsbetriebe opened the new Westbahnhof stop for the U6, a completely new building 53 meters east of the previous station. The old Otto Wagner station from 1898 was finally obsolete and was later filled in. The underground access routes themselves were retained in order to be able to use them as a road tunnel in the future if necessary.