Imperial regalia

The Reichskleinodien (also: Reichsinsignien or Reichsschatz ) are the rulership insignia of the emperors and kings of the Holy Roman Empire . The most important parts of this are the imperial crown , the holy lance and the imperial sword . Since 1424 they have been in the Heilig-Geist-Spital in Nuremberg for several centuries , due to the French threat from the coalition wars since 1800/1801 they are kept in the treasury of the Vienna Hofburg .

The imperial regalia are the only almost completely preserved crown treasure from the Middle Ages.

Concept of imperial regalia

For the period up to the High Middle Ages , the concept of imperial regalia or insignia is actually inappropriate, since the imperial idea in connection with the insignia only emerged more strongly later. The Latin names, for example, for the treasure trove of insignia vary between expressions such as: insignia imperialia, regalia insignia, insignia imperalis capellae quae regalia dicuntur and similar expressions. In an inventory list of Trifels Castle from 1246, these are again called keystone symbols .

It is therefore clear that at this time the reference to the person and the office of the ruler is decisive for the designation. In addition, the holdings of the imperial treasure were not stable until the time of Charles IV . Pieces were most likely added, removed, or exchanged for other pieces.

Nevertheless, for pragmatic reasons, the term “ imperial regalia” or “ imperial insignia” is usually used for this period . An early document for imperial regalia dates from 1580.

Components

The imperial regalia consist of two different parts. The larger group are the so-called "Nuremberg gems". The name comes from the fact that they were kept in Nuremberg from 1424 to 1796 . This group includes the imperial crown, parts of the coronation robe , the imperial orb , the scepter , the imperial and ceremonial sword , the imperial cross , the holy lance and all other relics with the exception of the Stephansbursa .

The aforementioned Stephansbursa , the imperial gospel and the so-called saber of Charlemagne were kept in Aachen until 1794 and are therefore referred to as the Aachen gems . It is not known since when these pieces were assigned to the imperial regalia and kept in Aachen.

| Aachen gems | Probable place and period of origin |

|---|---|

| Imperial Gospel Book (Coronation Gospel Book ) | Aachen, end of the 8th century |

| Stephansbursa | Carolingian, 1st third of the 9th century |

| Saber of Charlemagne | Eastern European, 2nd half of the 9th century |

| Nuremberg gems | Probable place and period of origin |

| Imperial Crown | West German, 2nd half of the 10th century |

| Reichskreuz | West German, around 1024/1025 |

| Holy lance | Lombard, 8./9. century |

| Cross particles | |

| Imperial sword | Scabbard German, 2nd third of the 11th century |

| Orb | West German, around the end of the 12th century |

| Coronation mantle (cope) | Palermo , 1133/34 |

| Alba | Palermo, 1181 |

| Dalmatica (Tunicella) | Palermo, around 1140 |

| Socks | Palermo, around 1170 |

| Shoes | Palermo, around 1130 or around 1220 |

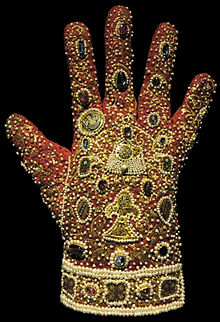

| Gloves | Palermo, 1220 |

| Ceremonial sword | Palermo, 1220 |

| stole | Central Italian, before 1338 |

| Eagle dalmatica | Upper German, before 1350 |

| scepter | German, 1st half of the 14th century |

| Aspergils | German, 1st half of the 14th century |

| Reliquary with the chain links | Rome or Prague , around 1368 |

| Reliquary with a piece of clothing by the Evangelist John | Rome or Prague , around 1368 |

| Reliquary with a chip of Christ's crib | Rome or Prague , around 1368 |

| Reliquary with the arm of St. Anne | probably Prague after 1350 |

| Reliquary with a tooth of John the Baptist | Bohemian, after 1350 |

| Sheath of the imperial crown | Prague, after 1350 |

| Cloth reliquaries with a piece of the tablecloth of the Last Supper and the apron of Christ at the ablution |

history

middle Ages

In high medieval lists, the inventory of imperial regalia is usually given as five or six objects. Gottfried von Viterbo lists the following items: the holy cross, the holy lance, the crown, the scepter, the apple and the sword. However, other lists do not mention the sword.

The extent to which the mentions in the High and Late Middle Ages actually relate to the pieces kept in Vienna today depends on various factors. Most of the time, it was only said that the ruler was “dressed in imperial insignia” without describing the specific objects. Allocation to today's objects of the Holy Lance and the Reichskreuz is problem-free, since their origin is before this time and there is sufficient evidence for the actual correspondence.

Origin of the current stock

The oldest piece of imperial regalia is the Holy Lance, which probably goes back to Heinrich I. It is a winged lance from the Carolingian era, from the leaf of which an opening was chiseled, into which an iron pin was inserted and fixed with silver wires. According to legend, it is said to be a holy nail from the cross of Jesus .

The current imperial crown can probably only be proven around 1200, when it becomes recognizable in medieval poetry based on the orphan , a large and prominent gemstone ( see also: first mentions of the imperial crown ). For the most part, however, proof of this is only possible much later on a mural in Karlstein Castle near Prague .

Even with the imperial and ceremonial swords, it is difficult to determine since when they became part of the imperial regalia. In the case of the other pieces, the chronological allocation to the inventory of imperial regalia is similarly difficult.

Travel through the empire

Up until the 15th century, the imperial insignia had no permanent place of storage and sometimes accompanied the ruler on his travels through the empire. It was particularly important to have the insignia in disputes about the legality of rule. Some imperial castles or seats of reliable ministerials are known as storage places during this time:

- Benedictine Abbey Limburg near Dürkheim (Palatinate) (11th century)

- Harzburg (11th century)

- Kaiserpfalz Goslar (11th, 13th century)

- Hammerstein Castle (on the Rhine) (1125)

- Trifels Castle near Annweiler (12th, 13th centuries, with interruptions)

- Palatine Chapel Hagenau (12th, 13th centuries, with interruptions)

- Waldburg Castle near Ravensburg (approx. 1220–1240)

- Krautheim an der Jagst Castle (probably 1240–1242)

- Kyburg Castle near Winterthur (1273–1322, with one interruption)

- Stein Castle near Rheinfelden AG (around 1280 under Rudolf I (HRR) )

- Old Court in Munich (under Ludwig the Bavarian , 1324-1350)

- Vitus Cathedral (Prague) and Karlstein Castle in Bohemia (approx. 1350 / 52–1421)

- Plintenburg and Ofen in Hungary (1421–1424)

Nuremberg

Handover to Nuremberg

The Roman-German King Sigismund transferred the imperial regalia to the imperial city of Nuremberg with a document dated September 29, 1423 for safekeeping "for eternity, irrevocable and incontestable" and had them taken to the city the following year, where they remained until the end of the 18th century. Century were kept. They arrived on March 22nd of the following year from Plintenburg in the free imperial city and from then on were kept in the church of the Heilig-Geist-Spital . They left this place regularly for the healing instructions (annually on the fourteenth day after Good Friday) on the main market (Nuremberg) and for the coronations in the Frankfurt Cathedral .

Albrecht Dürer proudly inscribed his painting, made by order of the city in 1512/14, which shows Charlemagne - historically incorrect - with the gems:

"This is the figure and

image equal to emperor Karlus who makes the Roman Empire

Den teitschen under tenig

His crown and

clothing are highly respected in Nurenberg all Jar

with other haitum apparently"

Ceremonial ornament

At least since the time of the Enlightenment, the imperial regalia no longer had any constitutive or strengthening character for the empire. They were only decorative ornaments for the coronation of the emperors, all of whom came from the House of Habsburg . The whole " fuss " around the coronation and the imperial regalia was mostly felt to be ridiculous. This is proven by various sources, such as Johann Wolfgang Goethe , who was an eyewitness to the coronation of Joseph II in Frankfurt am Main on April 3, 1764 . Emperor Franz I had his 18-year-old son elected and crowned king while he was still alive, which only happened once in the 18th century. So that both majesties could appear in the imperial regalia, an imitation of the coronation cloak was made for Emperor Franz , which, according to Goethe, was also comfortably and tastefully made. The young king, on the other hand, wore the actual coronation regalia, and Goethe wrote about it in Poetry and Truth (Part I, 5th book):

“The young king dragged himself along in the enormous pieces of clothing with the jewels of Charlemagne, as if in disguise, so that he himself, looking at his father from time to time, could not refrain from smiling. The crown, which had to be fed a lot, stood out from the head like an overarching roof. "

A few years later, Karl Heinrich Ritter von Lang wrote something similar about the coronation of Leopold II in 1790 in a report that can safely be described as a hateful caricature:

"The imperial robe looked as if it had been bought at the flea market, the imperial crown as if it had been forged together by the most inept coppersmith and covered with pebbles and broken glass, on the alleged sword of Charlemagne was a lion with the Bohemian coat of arms."

Escape

When French troops advanced in the direction of Aachen in 1794 , the pieces located there were brought to the Capuchin monastery in Paderborn . In July 1796 French troops crossed the Rhine and shortly afterwards reached Franconia. Its commander, General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, was supposed to bring France into possession of the imperial regalia. In addition to the French attack, they wanted to prevent Prussia from seizing the imperial regalia.

When French troops reached Nuremberg on August 9, 1796 , the imperial regalia had already been taken away, as on July 23 the most important parts of the imperial regalia (crown, scepter, orb, eight pieces of regalia) were carried out by Nuremberg Colonel Johann Georg Haller von Hallerstein from Nuremberg to Regensburg , the meeting place of the Reichstag , where they arrived the following day. On September 28, the remaining parts of the treasures were also brought to Regensburg. Since this escape , parts of the treasure have been missing.

The intention was to give the imperial regalia to the Reichstag for safekeeping while the French were threatened. That is why they had contacted the imperial crown commissioner Johann Aloys Josef Freiherr von Hügel and wanted to turn to the Mainz ambassador to the collegiate director Strauss. At the urging of Hügel, however, in order not to endanger the secrecy of the action, the Nuremberg deputation did not contact Strauss.

The imperial regalia remained in the St. Emmeram monastery until 1800 , from where they were transported to Vienna on June 30th . The handover there is booked for October 29th. The pieces from Aachen were brought to Hildesheim in 1798 and did not reach Vienna until 1801.

Efforts to repatriate the imperial regalia

After the imperial regalia were rescued to Vienna and the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved, Nuremberg and Aachen tried several times to return the jewels to their respective storage locations. Legal, political and emotional means were used from the start.

Nuremberg complained

Just a few days after Emperor Franz II had laid down the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the city of Nuremberg asked the imperial crown commissioner Johann Aloys Josef von Hügel, who had fled the jewels to Vienna, “whether the deposited objects were now can be returned without further ado or a special request is therefore required ”. Hügel then informed the magistrate that Nuremberg was no longer an imperial city and that the former emperor considered the privilege granted to store the treasures to have expired. The city let the matter rest for now.

Fifteen years later, in 1821, the now Bavarian city made a request to the royal Bavarian government to take steps to transfer the treasures. However, this refused the request for various reasons.

In 1828, the Munich archive secretary, Klüber, suggested that an expert report should be drawn up to justify the return of the treasures. This proposal was submitted to the Bavarian king and approved. The royal government continued to regard the matter as a matter for the city of Nuremberg. The report and another one from the secretary were inadequate and could be refuted by the existing documents of the city, so that a different approach was discussed. For example, Nuremberg should try to put public pressure on Vienna with the help of articles in widely read magazines. Due to various difficulties, such as legal reports not drawn up, non-activities by the city of Nuremberg and bureaucratic devices, this also failed. From February 1830 on, repatriation activities were suspended for more than 28 years.

Aachen also complains

Aachen, which had become Prussian , where the saber of Charlemagne, the imperial gospel and the Stephansbursa were kept until 1794, asked the Prussian government in 1816 to work towards the return of the treasures in Vienna. The city decided, however, not to raise its concerns in Vienna, as the imperial regalia "were never a specific property of the city of Aachen and were taken away from there at a time when Aachen was not yet united with the Prussian state".

In 1834 the city made a direct push to the Austrian Emperor Franz I to return the treasures. Franz I then commissioned his State Chancellor Metternich to provide an expert opinion. This expert opinion, drawn up by Josef von Werner, came to the decision that "the requesting Collegial Foundation does not have an actual legal reason to justify its request, and important political considerations do not make it advisable to deviate from the currently claimed legal basis".

A similar request from March 1856 was also rejected on the basis of this expert opinion.

Period of National Socialism and the post-war period

At the urging of the Lord Mayor of Nuremberg, Willy Liebel, and with Adolf Hitler's consent, the imperial regalia were returned to Nuremberg after the annexation of Austria . In a secret operation, they were transported to Nuremberg on a special Reichsbahn train at the end of August 1938. Hitler had precise ideas about the exhibition of the crown jewels and planned a final altar-like installation of insignia in the already under construction convention center on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds . So he wanted to take up the tradition of the Holy Roman Empire as the leading power in the Middle Ages and combine it with the idea of the “ Thousand Years Reich ”, in accordance with the National Socialist ideology of the empire and the greater area .

Until the completion of the congress hall, Hitler agreed to a provisional display of the imperial regalia in the Katharinenkirche . However , he emphatically refused to be placed in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum . However, the three Aachen gems were also transferred to Nuremberg, although they had never been kept in Nuremberg before.

The imperial regalia were only on public display for a short time. During the Second World War , the increasingly violent air raids on Nuremberg made it necessary to store the imperial regalia in the historical art bunker and pannier bunker for protection . As the front approached during the last months of the war, Lord Mayor Willy Liebel, together with two city councilors and the senior building officer, decided to hide the gems from the Allied troops. There was also the fear that the SS might destroy the imperial insignia in the madness of the last few days. That is why they were welded into specially prepared copper containers and walled in on March 31, 1945 in a hidden niche in the bread cellar.

Although absolute secrecy about the hiding place was agreed and a deception maneuver on April 5 was supposed to simulate the removal of the jewels, the American occupation authorities were able to find and secure the imperial regalia. This was achieved by putting those involved in the action under pressure with the charge that they wanted to use the imperial regalia as possible symbols for a National Socialist resistance movement. The two city councilors were sentenced to imprisonment and fines by an American military tribunal for “hiding works of art or providing false information”. Liebel had already died at the end of the battle for Nuremberg .

Since the American occupation authorities feared the symbolic content of the imperial regalia for a possible National Socialist resistance movement and because the Allied Control Council had decided to comply with the request of the Austrian federal government for repatriation to Vienna, the artifacts packed in boxes were flown to Vienna in early 1946. Since 1954, the imperial regalia have been exhibited again in the treasury of the Vienna Hofburg.

Copies of the imperial regalia

In the course of time, various replicas of parts of the imperial regalia were made. Today in Nuremberg ( Fembohaus City Museum ), Aachen (Coronation Hall of the City Hall ), Frankfurt am Main ( Historical Museum , made in 1913) as well as the Waldburg ( Upper Swabia ) and Trifels Castle (in the Palatinate Forest ) replicas of the core pieces of the gems, i.e. the Crown, orb and scepter. The exhibits to be seen today on the Trifels were carried out by Erwin Huppert (Mainz). In Schwäbisch Gmünd , the oldest town in the Staufer , replicas of the core pieces, such as scepter, apple, sword, gloves, crown and shoes, as well as the coronation coat have been made since 2012. The finished pieces, imperial crown and apple, were presented to the public on June 29, 2013.

At least one copy of the coronation regalia was made earlier. On April 3, 1764, Joseph II was crowned Roman-German King in Frankfurt while still alive and in the presence of his father, Emperor Franz I. On this occasion, a second coronation mantle was made for Francis I, which was modeled on the first. The successful execution of this work is proven by a description by the eyewitness Johann Wolfgang Goethe in his work Poetry and Truth (Part I, Book 5):

"The emperor's house robe of purple silk, richly adorned with pearls and stones, as well as crown, scepter and orb, fell into the eyes: for everything was new about it, and the imitation of antiquity tasteful."

However, Goethe was wrong when he said that the crown was also a replica. Rather, on this occasion Franz I wore the miter crown of Emperor Rudolf II , which became the crown of the Austrian Empire half a century later .

See also

- History of the city of Nuremberg

- Lothark Cross

- Children's crown of Otto III.

- Orphan (imperial crown)

literature

- Franz Bock: The German imperial regalia with the addition of the coronation insignia of Bohemia, Hungary and Lombardy in a historical, liturgical and archaeological relation , 1st part (simple edition). Vienna 1860.

- Julius von Schlosser : The treasure chamber of the very highest imperial house in Vienna, represented in its most distinguished monuments . With 64 plates and 44 text illustrations. Schroll, Vienna 1918 ( digitized version )

- Hermann Fillitz : The insignia and jewels of the Holy Roman Empire . Schroll, Vienna / Munich 1954.

- Fritz Ramjoué: The ownership structure of the three Aachen imperial regalia . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1968 (see dissertation Cologne 1967). (On this: Aachen versus Vienna. The dispute over the three imperial regalia continues . Article in the online archive of the time from April 19, 1968).

- Wilhelm Schwemmer: The Reichskleinodien in Nuremberg 1938–1945. In: Communications from the Association for the History of the City of Nuremberg. Vol. 65, 1978, ISSN 0083-5579 , pp. 397-413, ( online ).

- Ernst Kubin: The imperial regalia. Your Millennial Way . Amalthea, Vienna / Munich 1991, ISBN 3-85002-304-4 .

- Alexander Thon: The realm of treasures. Once at Trifels Castle: emblems of rulership, relics and coronation robes . In: Karl-Heinz Rothenberger (Ed.): Palatinate History, Vol. 1.2, verb. Aufl. Institute for Palatinate History and Folklore, Kaiserslautern 2002, ISBN 3-927754-43-9 , pp. 220-231.

- Heinrich Pleticha : The shine of the empire. Imperial regalia and coronations as reflected in German history . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau a. a. 1989, ISBN 3-451-21257-9 (reprint: Flechsig, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-88189-479-9 ).

- Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Nobiles Officinae. The royal court workshops at Palermo during the Normans and Staufers in the 12th and 13th centuries. Milano 2004, ISBN 3-85497-076-5 .

- Peter Heigl: The Reichsschatz in the Nazibunker / The Imperial Regalia in the Nazibunker. Nuremberg 2005, ISBN 3-9810269-1-8 .

- Society for Staufer History (Hrsg.): The imperial regalia, symbol of rule of the Holy Roman Empire . Göppingen 1997, ISBN 3-929776-08-1 .

- Josef Johannes Schmid : The imperial regalia - objects between liturgy, cult and myth . In: Bernd Heidenreich , Frank-Lothar Kroll (ed.): Election and coronation . Societäts Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-7973-0945-7 , pp. 123-149.

- Sabine Haag (Ed.): Masterpieces of the Secular Treasury. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-85497-169-6 .

- Jan Keupp , Hans Reither, Peter Pohlit, Katharina Schober, Stefan Weinfurter (eds.): "... die keyerlichen zeychen ..." The imperial regalia - emblems of the Holy Roman Empire. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7954-2002-4 .

Movies

- Signs of rule, history of the imperial regalia , BR 1996, a film documentation by Bernhard Graf

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Keyword Reichskleinodien , in: German Legal Dictionary, Volume XI, p. 649, online

- ↑ Alexander Thon: From the Middle Rhine to the Palatinate. On the prehistory of the transfer of the imperial insignia from Hammerstein Castle to Trifels Castle in 1125 . In: Jahrbuch für Westdeutsche Landesgeschichte 32, 2006, pp. 35–74.

- ↑ Annamaria Böckel: Holy Spirit in Nuremberg. Hospital foundation & place of storage of imperial regalia (= Nürnberger Schriften Vol .; 4). Böckel, Nuremberg 1990, ISBN 3-87191-146-1 .

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang Goethe: Poetry and Truth . First part, fifth book. ( Description of the coronation of Joseph II as Roman-German king )

- ^ A b c Klaus-Peter Schroeder: The Nuremberg imperial regalia in Vienna . In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History. German Department . tape 108 , no. 1 , 1991, ISSN 2304-4861 , pp. 323-346, here p. 334 .

- ↑ a b c d e Klaus-Peter Schroeder: The Nuremberg Reichskleinodien in Vienna . In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History. German Department . tape 108 , no. 1 , 1991, ISSN 2304-4861 , pp. 323-346, here pp. 323-327 .

- ↑ a b Almut Höfert: Royal Object History. The coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire . In: Transcultural entanglement processes in the premodern . tape 3 . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-044548-0 , pp. 156-173, here p. 169 , doi : 10.1515 / 9783110445480-008 .

- ↑ Crown - Power - History. Nuremberg at a glance. Museums of the City of Nuremberg, accessed on January 18, 2017 .

- ^ Imperial insignia in the Frankfurt Historical Museum .

- ↑ Treasury. Waldburg , 2016, accessed December 31, 2016 .

- ↑ Presentation of the first two Reichskleinodien on Saturday . ( staufersaga.de [accessed on July 5, 2017]).