Ste-Eulalie-Ste-Julie (Elne)

Today's Co-Cathedral Sainte-Eulalie-et-Sainte-Julie ( Catalan Santa Eulalia d'Elna ) is erected in the 11th century and 15th century extended in the 13th church in the southern French town of Elne ( the Pyrénées-Orientales , Region Okzitanien ), which is about 12 kilometers as the crow flies southeast of the city center of Perpignan and barely six kilometers from the eastern Mediterranean beach.

It is one of the most important sacred architectural monuments in the region and served from 568 to 1605 (according to other sources until 1601 or 1602) as the bishopric of the diocese of Elne . At least from its founding date , the cathedral undoubtedly included convent buildings of a monastery in which the bishop lived with his community of canons . However, the sources give no information about the size and appearance of the predecessors of today's buildings.

history

Visigoth roots / founding of a bishopric

The continued existence of urban life, even if only to a modest extent, after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, Elne owed the - albeit quite late - founding of a bishopric, which made it an important church town. This has resulted from the changeful fate of the kingdom that the Visigoths had established in southern France and Hispania . After the battle of Vouillé was victorious for the Franks in 507, this empire was divided and only comprised Septimania on the northern side of the Pyrenees . To at least partially compensate for this situation, the fortified settlements ( castra ) Carcassonne and Elne were raised to the rank of cities in 568 and each was assigned a bishopric.

The three sarcophagi in the east gallery date from the Visigothic period (6th – 7th centuries) (see convent rooms and cloister , under cloister).

Predecessor structures

According to a source, it is generally assumed that a wisigothic ( pre-Romanesque ) cathedral, and thus also the first episcopal monastery, was built in the 6th century (around 571) in the lower town of Elne and then lasted for about 300 years. Nothing is known about its size and appearance. Possibly it was already dedicated to one of the same patrons as today's church. From the year 861 new pre-Romanesque monastery and church buildings were erected at the highest point in the upper town, the predecessors of today's buildings. The sources do not provide any information about their extent and appearance. They lasted for about 200 years. The dedication is about the same as the previous church.

Investiture controversy and Augustinian monastery

Since the beginning of the 10th century, almost exclusively members of the local high nobility held the bishopric. “Up to the year 1064 only bishops with the first names Oliba, Berengar or Suniaire ascended the episcopal throne of Elne; they probably all came from the dynasty of the Counts of Roussillon, Cerdagne and Barcelona. "

The Gregorian reforms of the 11th and 12th centuries had set themselves the task of freeing the church from this lay investiture and at the same time bringing church customs back to the ideal of the Christian gospel. However, the undertaking met with great resistance from the aristocracy, where the family of the Vice Count of Castelnou stood at their head. In order to restore church patronage, the Bishop of Elne had to seek help from the Archbishop of Narbonne and the Counts, who were delighted to be able to resist the rule of the Vice Count. The aforementioned archbishop, the bishops of Gerona and Carcassonne, as well as Raimund, the count of Cerdagne, met in Elne in 1058 to celebrate the "restoration of the seat of Sainte-Eulalie", which is to be understood as the church patronage, the had been belittled by "the destroyers of the Church", was renewed. At that time, the chapter also revived, which now comprised 24 canons, but whose statutes were initially not changed. It was not until the beginning of the 12th century that it submitted to a strict community life and adopted the rules of St. Augustine . These circumstances also had consequences for the development of the buildings of the bishopric.

Construction of today's structures

Already in 1042 an individual donated 10 "mancusi" (Arabic dinars) to the church of Sainte-Eulalie (the mancus is a gold coin with a low precious metal content, 30 mancusi was the equivalent of a horse at that time). On September 25, 1057, the Countess Ermessinde of Barcelona made her will. She was a great lady whose style of government did not appeal to everyone, but whose strong personality had shaped the political life of Catalonia for half a century. She bequeathed 150 mancusi to the bishopric of Roussillon, which were intended for the church of Sainte-Eulalie ( ad ipsa opera ). For the canons she added another 50 mancusi, and Bishop Artal I (1064-1071) also received this amount.

In the first half of the 11th century, the renovation of the cathedral and the convent building in Romanesque architectural style began, and certainly larger than and instead of the pre-Romanesque predecessor buildings, which were just 200 years old. The construction of the choir apse is dated to the year 1040. As with numerous other consecutive church buildings, the older buildings were demolished and the new buildings were constructed in such sections that rooms were always available for celebrating masses and for worshiping relics. The same applied to the premises of the episcopal convent.

The new building at that time largely corresponded to the buildings preserved today, in which the later conversions and additions from the 12th to 15th century, for example the sculpture of the cloister, its vaults, the additions to the chapels on the south side of the nave and the retrofitting of some ribbed vaults of the church.

The original upper floor of the cloister and the surrounding east and west wings of the convent rooms are no longer preserved today, apart from small remains.

Finally, the main altar was erected in 1069, as reported by a beautifully chiseled inscription on two marble tablets. From the first part of the text it can be seen “that in the same year Bishop Raimund ordered the Count of Roussillon Gauzfred and his wife Azalaïs, as well as the inhabitants of the whole area of all classes, the powerful and the weak, the rich and the poor, to build the altar in honor of our Lord Jesus Christ and the virgin and martyr Eulalie, patron saint of the Duiocese, for God and the good of their souls ”. The second part of the text asks that “the men and women who contribute to the building of the altar through their alms are found worthy to take their place among the elect, as are their parents.” This lengthy text refers to a very solemn ceremony for which numerous people had come together.

From this document it emerges, among other things, that at that time only one patron saint was mentioned, the martyr Eulalia (Spain). The known sources do not provide any information about when the second patron saint, the martyr Julia of Corsica , who is always mentioned today , was added.

Finally, the Romanesque new buildings were largely completed ready for use in the second half of the 11th century (for type and scope, see section Buildings ). Of the originally planned two towers above the facade, towards the end of the 11th century only the southern one reached a little further up the height of the massive westwork and ended under the two bell-storeys that were later raised on all sides. The planned northern bell tower was never built. In its place, a significantly slimmer brick tower was built later, which does not come close to the architectural quality of the southern one. The south tower received its last two floors, still in Romanesque style, also later, which can be recognized by its more advanced stone carving.

Bishop Artal III. and his cathedral chapter also gave the inhabitants of Elne “permission to fortify the city and to use armed force to defend themselves against injustice and abuse of which they would become victims.” This document is dated February 6, 1156.

St. James pilgrimage

The pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain began towards the end of the 11th century . Its heyday was in the first half of the 12th century, when hundreds of thousands of pilgrims traveled south every year. The Way of St. James in France was formed from four main routes, accompanied by a network of numerous secondary routes. Numerous new churches, monasteries, hospices, hostels and cemeteries were built along these paths, and existing facilities were expanded to meet the new requirements. (P. 25) For a pilgrimage church, above all, large areas of movement were needed for the numerous pilgrims , such as the ambulatory and side aisles , galleries and as many chapels as possible for the presentation of relics and their veneration.

Like numerous other very important monasteries, Elne was located on a busy byway of the many pilgrimage routes of the Way of St. James, which were concentrated in France north of the Pyrenees and led to the few crossings to northern Spain. This was the "Chemin du Piemont", which reached from Salses via Perpignan at the northern foot of the Pyrenees, mostly in valley bottoms such as that of the Têt , to the northern end of the mountain range.

In any case, the new construction of the Cathedral of Elne and its convent building was essentially completed with the use of these important pilgrimage movements and could participate in the generous donation of the pilgrims. So the canons soon had sufficient means at their disposal to be able to afford the vaulting of the cloisters and the sculpture of the cloister arcades, using the best sculptors known at the time, and that for several generations. This work extended from the 12th century to the first half of the 14th century. After the south gallery, initially covered with a simple wooden beam ceiling, the galleries in the west, north and east followed one after the other, but with “modern” ribbed vaults. Apparently the funds were then sufficient to replace the beamed ceiling of the south gallery with a Gothic vault.

descent

As the dispute over Aquitaine between England and France rose after the mid-12th century, pilgrimage declined and the wars of the 13th and 14th centuries brought a dramatic slump. (P. 25) With this these sources of money dried up almost completely. The episcopal monastery again had to limit itself to the income from the pilgrimages in the region.

In 1285, under the rule of the Counts of Barcelona , the city of Elne was sacked, the cathedral set on fire and the people massacred by the French troops of Philip the Bold . The damage caused by the fire appears to have been limited as there is no mention of it in the sources.

At the end of the 13th century, in the sixth yoke , right next to the southern apsidiole , the first Gothic chapel was added to the south aisle with a ribbed vault . This chapel was built at the instigation of Bishop Raimon de Costa (1289-1310), he has his tomb there. The other tombstone in this chapel is that of his brother Petrus Costa. He was archdeacon of Jàtiva (now Xàtiva ) in the diocese of Valencia , canon of the archbishopric church of Narbonne , precantor of the cathedral of Elne and died on August 13, 1320.

Attempt at a Gothic extension

At the beginning of the 14th century, the bishops of Elne decided to enlarge the cathedral and replace the Romanesque staggered choir with a Gothic choir with access. This suggests that the former income from the time of the pilgrimages to St. James had not yet been used up. This should consist of seven polygonal chapels in plan, the partition walls and their extensions would have formed strong buttresses to absorb the shear forces of the circumferential vault via outer buttresses . This planning, probably under Bishop Ramon V (1311-1312), could be started but not completed.

Bishopric moves to Perpignan

The prelates gradually moved to nearby Perpignan, which, thanks to the presence of the Majorca royal court and the boom in trade and industry, had become an economically and politically important city. An art center also began to develop here. Compared to these diverse activities, Elne looked like an insignificant little market town . Already at the time of Bishop Berenger von Argilaguers (1317-1320) the idea of completely rebuilding the collegiate church Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Perpignan and according to an imposing plan, also with regard to the intention to one day move the bishopric there entirely relocate. This meant the end of the Gothic choir planned in Elne.

Today, the lower wall sections of the chapels with their buttresses barely rise above its underground foundation walls over five meters. Even this poor result made two construction phases necessary. The use of two different building materials, sandstone for the lower section and limestone for the upper section, testifies to the two phases in the 14th and early 15th centuries. The walls of these chapels, which barely protrude from the site, are a reminder of the great project, enclose a room that has remained empty and astonish the unsuspecting visitor who wrongly suspects a work of destruction here. At least the failed Gothic project got the beautiful Romanesque choir head.

The heavy weight of the southern bell tower had caused considerable damage to the masonry. In 1415 the young master builder Guillermo Sagrera of Mallorca, architect of the Loge de mer in Palma and the Castel Nuovo in Naples, was commissioned to restore the tower. During the securing work, he used wooden tie rods and reinforced the south-western lower corner of the tower with massive, outwardly steeply sloping wall supports made of stone blocks .

The two Gothic chapels, which are attached to the south aisle in the 5th and 4th yoke, date from the middle of the 14th century, but were built with a time lag. One of the two was built by Gilles Batille, a beneficiary of the cathedral, who died in 1341.

The connecting room to the south portal and the last two chapels in yokes 3 to 1 date from the 15th century and were first mentioned in 1441 and 1448.

By Pope Clement VIII the diocese was renamed in 1601 under the bishop Onofre Reart (1599-1608) to the diocese of Perpignan-Elne and the metropolitan diocese of Narbonne . At the same time, the relics of the two patron saints were moved to Perpignan. The cathedral, which had been a bishopric until then, became the parish church of Elne. With the dissolution of the bishopric, however, the monastery does not seem to have been given up, as some later causes of the canons are known, such as the installation of a baroque canopy over the altar in the choir apse in 1721.

In this context, there are assumptions that a former crypt under the choir apse was filled in before the new canopy was erected and the formerly higher floor of the apse was lowered to its current level. These assumptions are based on the fact that today at the top of the apse there is a small apsidiole, which is flanked by two small arched windows below the large windows of the choir apse, which are said to have provided light for the crypt.

Neither the Wars of Religion (1562–1598) nor the French Revolution (1798) evidently left any significant damage to the buildings.

Modern times - destruction of the upper floor of the cloister

The former two-storey cloister with the wings of the convent rooms surrounding it in the east and west was still preserved at the time of the revolution. The upper floor of this building must have been in a very dilapidated condition, so it was demolished in 1827. Presumably the ground floor of the cloister and the east and west wings of the convent building were then covered with new monopitch roofs. A number of cantilever consoles on the high wall of the north aisle and on the outer walls of the cloister, which are still partially rising in the west and east and on which the ridge purlins of the upper floor originally rested, bear witness to the former upper floor of the cloister . Two short sections of the upper floor of the convent wing have been preserved, namely the one directly adjacent to the nave.

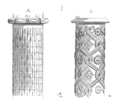

It is generally assumed that the richly carved marble pieces come from this demolition, which the antique dealer Gouvert, who had made a name for himself as the "cloister dealer", bought in Elne. So he also bought twelve capitals together with twelve column shafts and five cover plates. After changing hands several times, these pieces were lined up in pairs in the castle of Villevêque (Maine-et-Loire) and can be viewed there. The cylindrical, polygonal or twisted columns and capitals are understandably less high than those of the lower cloister galleries.

The twelve columns with capitals are only a small part of those that once stood on the upper floor of the cloister, there were also 64 pieces, or 32 pairs, without the 12 square pillars, if one assumes that the upper cloister is the same Number of pillars and columns as on the first floor.

In the 19th century the three windows of the choir apse must have been enlarged. In order to verify the presumed crypt, which is said to have been filled before the erection of the canopy, it was decided at the beginning of the 1970s to expose the floor of the apse around the foundations of the canopy down to the Romanesque level. A crypt could not be found. Even if one was planned, it was never completed, because even before it was built it became superfluous due to the further development of the liturgy. Accordingly, they refrained from vaulting them and building the initially planned elevated choir floor.

In order to meet the resolutions of the Second Vatican Council (October 11, 1962 to December 8, 1965) and the reform of the liturgy, it was decided to separate the altar and the canopy. The altar was set up a little in front of the canopy. The old altar plate from the 11th century was used again, which was placed on the upturned ancient tombstone as before. The two marble slabs with engraved inscriptions were used to close the vacated space in the baroque ensemble.

Buildings

Dimensions / floor plan

approximate dimensions, measured from the floor plan and extrapolated

Cathedral:

- Length outside (without Gothic choir): 49.30 m

- Outside width of the nave, with chapels to the south: 22.80 m

- Inside width of the nave, without chapels: 17.40 m

- Inner width of the central nave: 7.40 m

- Inside width of the choir bay: 7.50 m, depth: 1.90 m

- Width inside choir apse: 6.90 m

- Deep apsidioles, 1.90 m

- Height of the central nave at the apex: 16.00 m

- Height of aisles at the apex: 11.20 m

- Max. Width of the Gothic choir outside, over everything: 27.20 m

- Max. Outward projection of the Gothic choir, over everything: 21.40 m

Cloister with convent buildings:

- Courtyard: south side: 15.00 m, west side: 13.60 m, north side: 14.60 m, east side: 13.60 m

- Width of the south gallery inside: 2.80 m, west and east gallery: 3.30 m, north gallery: 3.00 m

- Width of the convent building, outside: west wing 7.50 m, east wing 7.20 m

- Length of the convent building, outside: west wing 23.60 m, east wing 22.50 m

- Total extension of the convent building: on the nave: 38.90 m, on the north side: 36.60 m on the west wing, 23.60 m, on the east wing: 22.50 m

- Height of the columns with chapter, fighter, base and plinth: 1.76 m

- Height of the keystone of the cloister vault: 5.10 m

Outward appearance

cathedral

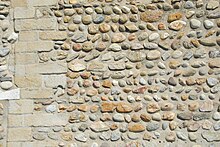

The exterior of the cathedral conveys the impression of sober severity and renunciation, which stems primarily from the use of simple materials, such as the pebbles and rubble stones cast in mortar. The house stones, which were often used inside the church, can only be seen outside on the choir head, on the facade and on existing or former component corners.

Longhouse

The unusually long central nave is covered over its entire length between the facade wall and the east wall by a gable roof sloping around thirty degrees and its longitudinal walls protrude about 1.5 to 2.0 meters above the pent roof ridges of the side aisles . Its roof surfaces, as well as all others except those of the apses, are covered with red hollow tiles in Roman format, also called monk-nun tiles, which protrude only slightly over stone eaves on the eaves. On the south side, the pent roof of the side aisle is dragged over the attached Gothic chapels. The eaves above the floor are equipped with copper gutters , and the rainwater is drained off in a controlled manner via rainwater pipes . At the gable corridors , the roof surfaces are slightly surmounted by the walls, the sloping tops of which are covered with zinc sheet .

Choir head

On the east wall of the central nave stands the almost equally wide, semicircular, rounded choir apse , which is covered by a half- conical roof, the wall connections of which remain about three meters below the gable arcades. The roof areas are covered with small-format slates on wooden formwork. Its eaves protrude slightly over a stone cornice.

About two thirds of its wall height is a not particularly deep blind arcade , which consists of a total of eleven slender, round-arched, sharp-edged blind arcades that are separated from one another by ten narrow pilasters and covered by smooth wedge arches . Round-arched window openings are recessed in the upper half of three arcades. The middle one takes up the whole width of the niche and its arch corresponds to that of the niche. The outer two keep a little distance from the arcade edges with their side and upper reveal edges. The windows are separated from each other and from the gable wall by two closed arcade niches. At the level of the arches, a cantilever profile runs over the niches and over the pilasters, the sloping visible edge of which is broken up by a double roller profile. This decor comes from the first phase of construction, which is dated around 1040. The arched fields of the arcades, separated in this way, are lined with diamond-shaped black, white and gray stone slabs placed on their tips, which are reminiscent of the incrustations of the Romanesque in Auvergne .

In the two blind arcades between the outer windows and the middle one, just below the arched fields, there is a strong, quarter-circle buttress arch , as we know it from the Gothic period . The arch is covered by stone slabs that slope outwards and merges into an unusually deep pillar. These buttresses were probably added at a later stage, as a result of cracks in the masonry of the choir head.

In the two blind arcades of the outer windows, a small round-arched window is cut out in the lower area, which was probably intended for a crypt under the choir apse that was still to be built . Below the middle window, directly above the adjoining site, a small apsidiole , almost three meters high, is built, which was probably also built for this crypt. The curved wall between the arcade arches and the eaves is completely closed. Their longer stones are neatly rounded to match the curvature of the wall.

As an extension of the side aisles , the choir apse is flanked by two apsidioles that turn the choir head into a staggered choir . The roofs of their roofs, in the form of half cones, are level with the arches of the blind arcades of the choir. Immediately above each a circular window, a so-called ox eye , is cut out, which is framed by a slightly protruding profile. The apsidioles almost completely cover the outer blind arcades except for their arched fields. The roofing and eaves correspond to those of the choir apse. The freely curved walls of the apses are stiffened with buttresses of rectangular cross-section, which end just under a meter below the eaves with sloping tops. Small arched windows are left open in the axes of the apsidioles.

South side nave

The south side of the nave consists essentially of the south aisle , which has disappeared in its entire length behind the Gothic chapel annexes, which were built in several phases from the end of the 13th to the middle of the 15th century. The side aisle and the row of chapels are covered by a shared pent roof. The south wall and the two top walls of the chapels are made of rounded field and brook pebbles, which are placed upright on top of one another in layers and are alternately inclined slightly to one side and in the next layer to the other. The south walls of the chapels are flush with one another. It started with the chapel at the southern end in front of yoke 6. This can be seen from the former two component edges of this section, which are layered on top of one another from large-format ashlar . The next sections followed westwards, each connected to the western component edges of the previous section and then each had only one new component edge. A total of three connections and four sections can be seen.

The small amount of windows, some with arched or only slightly pointed windows, barely reveals the Gothic style. The chapel in front of yoke 6 is illuminated by a circular ox-eye above half the height of the wall, the walls of which are made of neatly hewn stone. The next chapel in front of yoke 5 has a slightly pointed, medium-sized window in the upper half of the wall, the next but one in front of yoke 4 has a similar but slightly higher window. In the area of this chapel there is a large jump in the terrain in the form of a spacious twelve-step flight of stairs. The upper level of the terrain in the western area of yokes 1 to 3 roughly corresponds to the inner ground level, which suggests that the ground in the western half of the cathedral must have been considerably filled. This may also have led to the early thought of a crypt in this area.

The additions before the following three bays 1 to 3 were probably created in one construction phase. A side portal with a semicircular arch was created in the area of yoke 3, the reveal of which is decorated with several profiles. The base of the arch is marked by a fighter profile. The portal is enclosed in the lower half of the yoke by a smooth wall surface made of stone, which is covered by a segmented arch made of wedge stones at about half the wall height . A small rectangular window is cut out between the apex of the portal arch and the segment arch. In the wall section above there is a somewhat larger rectangular window with a frame in the Renaissance style . In the last two chapels in front of yokes 1 and 2, a large ogival Gothic window is left open, the height of which takes up almost the entire upper half of the wall. In this wall area, in the lower half of the wall, there are some horizontal layers of masonry made of flat red bricks, a good meter apart. This wall decor extends around the component edge up to the westwork. In this wall, a rectangular opening is cut out not far below the sloping verge. At the opposite end of the row of chapels there is an opening of the same type in the head wall at almost the same height. It is possible that these are ventilation openings in the roof spaces above the chapel vaults, which, however, would then also have to have been made in the partition walls of the chapels. Or maybe they belonged to a system of walkways and stairs in the attic spaces above the vaults, which are often found in such buildings and were part of a defense system. After all, there are also openings in the interior to other roof spaces above the vaults.

Westwork

The middle height of the westwork is as wide as the nave, without the chapels later added on the south side. It is essentially made of small to medium-sized house stones in different colors. The component edges are neatly joined from large-format stone. The west side of the lower two floors is the rather unadorned facade of the cathedral.

The lower floor of the westwork is more than twice as high as the second floor and about four times as high as the other tower floors. With the exception of the main portal, it is completely closed and ends with the parapets of the blind arcades on the second floor. From this height downwards, the south-western edge of the component and with it the adjoining wall surfaces continuously protrude slightly outwards. The opposite south-western edge of the building element and the adjoining wall surfaces, starting almost two meters deeper and continuing downwards, are increasing. However, this was only done afterwards in 1415 as an additional reinforcement with large-sized blocks of houses. On the west side, this facing ends abruptly below the center of the tower, with a vertical interlocking of the masonry, which indicates an intended short-term interruption of the work. This has now become almost 600 years.

The main portal on the lower floor is embedded exactly in the axis of the westwork, to which a six-step flight of stairs leads up on three sides. It is enclosed on three sides by a cladding made of smooth, light gray marble, the outline of which forms an elongated rectangle and ends at the top just below the beginning of the second floor. It protrudes slightly from the surrounding masonry. The rectangular portal opening contains a double-leaf wooden door, which is decorated with elaborately forged door hinges. The portal is enclosed on the sides and at the top by sharp-edged pillars and a lintel beam , which recede somewhat from the edging. Above the lintel beam, the semicircular curve rises as an extension of the lateral setbacks of the portal. It is enclosed by a wedge arch, flush with the surface, the width of the side border. Within this arch there is another Keilstein arch in extension of the side pillars and with the same setback. The closed arched field created underneath steps back again by the same paragraph into which a narrow profile is worked. The arched field consists of smooth stone slabs in the form of triangular pieces of cake, the joints of which meet in the middle of the top edge of the door lintel.

The second floor of the westwork begins at the level of the parapets of the blinds under the towers and is closed on the top by a cantilevered cornice that is led around the free sides of the towers and on the west side between the planned towers in the upper end of an approximately 30 degree inclined Gable passes. This gable triangle is also the western end of the gable roof over the central nave. In the area under the two planned towers, the respective wall section on the west side and on the two outer sides is each decorated with a triple arcature with " Lombard arched friezes ". Above the arcade, undecorated masonry surfaces remain about as high as half the arcade height up to the end of the floor. The three arcade niches are separated by two slender pilaster strips and are covered on top by two small, sharp-edged arcade arches that meet in the middle on a carved corbel. Under the north tower, the arcade arches are covered with an additional dark cantilever profile (basalt), and the otherwise very simple corbels have been replaced by dark, capital-like sculptures. On the east side, the arcades are almost completely covered by the pent roofs of the side aisles that adjoin here. The blind arch under the north tower has a recess of a round arched window at the lower edge of the central arcade. It is as wide as the arcade niche, and the apex of the arch is just below half the height of the niche. Its robes are greatly expanded outside. A similar, somewhat larger window is cut out in the axis of the otherwise undecorated west wall between the towers. Its vertex is slightly higher than that of the arcatures. The former gable field high above the central zone of the facade also belongs to the second floor. Of its decoration, only two arcades have survived at both ends, which correspond to those under the south tower. Their vertices rise, however, with the only partially preserved cantilever cornice above the west gable. Like the Lombard frieze, this motif is a legacy of the “premier art roman méridional”. When the cathedral was fortified, for example the crenellated parapet between the towers was added, these gable decorations were removed except for a few remains.

The towers, which are very different today, begin above the second floor of the westwork. According to one of the sources, the south tower corresponds to the two towers originally planned for both sides. The north tower planned in this way is said to never have been built after him. Today's much slimmer north tower is said to have been built much later. Its cross-section is about 2/3 as wide as that of the south tower. It may have been erected together with the religious wars that began around the middle of the 16th century, when the church's defense systems may have been upgraded. The defensive wall between the towers above the facade has a similar stone material as the north tower, namely a mixture of small-format house stones with flat red bricks. This combination of materials goes from the defensive wall directly into the tower wall.

The south tower stands on an almost square floor plan on all four floors, which are almost the same height. Its west and east sides are slightly narrower than the other two. The upper edges of the storeys are marked with the cantilever cornice familiar from the facade. All sides have four-arched arcatures of the same size on all storeys directly above the cantilever cornices with sharp edges, which are separated by slender pilaster strips and whose apexes reach just below the cantilever cornices. An exception to this is the south side of the top floor, which has only three arcades with correspondingly wider pilaster strips. The pilaster strips on the edges of the tower are slightly wider on the north and south sides than on the other two sides, which is caused by the not quite square outline.

In the lower tower floor, the arches have the same dark overlapping as on the north side of the facade. Most of all arcades are blind arcades. Only in the middle two arcades of the upper two floors are round-arched sound openings of the bell chamber recessed in the niches, the reveal edges of which are set back. On the south side of the top floor, only the middle of the exceptional three arcades is open. The half-right arcade is open on the lower floor of the tower on the same side. On this side you can also see on the second floor of the tower that the two middle arcades also have recessed edges of the reveal. This means that these arcades were already open and later bricked up again.

A parapet rises above the upper tower storey on all sides with the same outline, which carries battlements twice as high on the tower edges, the tops of which are double stepped on the sides. Between the tower edges, the parapets are crowned on the north and south sides by three angular battlements, on the somewhat narrower other two sides there are two battlements. The battlements are made of brickwork, except for those on the tower corners. The tip of a gently sloping pyramid roof covered with red tile shingles peeps out from behind the battlements.

Today's north tower replaced the tower that was once planned to have the same dimensions as the south tower. Not only is it significantly slimmer, but also a whole storey lower than the south tower. The lower basement, which is closed except for a round-arched door on the east side, extends slightly higher than the opposite of the south tower and is closed off by the well-known cantilever cornice. This floor consists of masonry of small-format house stones, in which various layers of flat red bricks are incorporated. The edges of the tower are made of these bricks, and the templates that extend laterally at intervals form a compound with the wall masonry. The aforementioned door connects the tower with an accessible roof area behind the tower and behind the parapet above the facade.

The second tower floor, built entirely of brick, is lower again, so that its upper end coincides with that of the second floor in the south tower. On each side of the tower of this storey, two round arched open acoustic arcades are left open. The elevation of the next and last tower floor is the same as that of the penultimate tower opposite. Here, however, only a single, very compact, round arched acoustic arcade is left out. This last tower floor is followed by a parapet with battlements, which is comparable to that of the south tower. Between the corner battlements there is only one angular battlement on each side. This tower is a whole story lower than the south tower.

Convent building

The convent buildings built on the north side of the cathedral from the cloister and the other convent rooms enclose the almost square cloister courtyard, which is slightly diamond-shaped due to the shifting of its northern structural members towards the east. All of the structural elements from the outer wall of the north aisle do not do this at a right angle, but are swiveled one to two degrees to the east. The sources do not provide any information about the cause. It would be conceivable that the previous buildings connected with one another with a similar distortion of the right angle and that this was adopted by using the foundation walls. In any case, this distortion is imperceptible on the spot.

Cloister / rough structure

The cloister is covered on all sides by four pent roofs inclined inwards by around 30 degrees, which merge into one another at their corners with valleys. In the south, their roofs lean against the significantly higher side wall of the north aisle and the other three against the less high-reaching partition walls between the cloister and the convent wings, which originally came under the roof of the upper floor. Today there is no convent wing on the north wall, so this wall supported the pent roof ridge of the north cloister gallery on the upper floor.

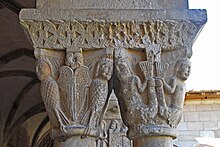

The four arcatures facing the courtyard show almost the same coarse structures of their construction. They stand on a good knee-high parapet and carry the 1.50-meter-high and 70-centimeter-thick walls that run above them, together with the courtyard-side loads from the vaults, once also the loads from the upper floor of the cloister. The arcades consist of three groups of arcades on each side of the courtyard, which are separated from each other and on the corners by pillars with a square cross-section. An arcade group consists of three round arched arcades, the wall-wide arches of which stand together on pairs of pillars. Each column is individually equipped with a carved capital, a profiled base and a square, partially carved plinth. The pairs of capitals are crowned by a joint profiled and sculpted fighter plate. The outer arches of each group stand on the pillar on projecting, mostly also sculpted, fighter plates in full pillar depth, which in turn are supported all around by a capital-like frieze with a relief sculpture. (Cloister sculpture see separate section)

Further convent buildings

The west and east wings of the convent building, which are also only ground floor today, are also covered with pent roofs, the roofs of which lean against the aforementioned partition walls. On the upper floor of the convent wing there are still the rooms or parts of the room directly adjoining the church, which are covered with a gable roof. The northern end walls of the convent wing protrude somewhat from the north wall of the cloister and show their verges here. The outside of this north wall, which is completely closed except for two Gothic windows, is stiffened by seven strong buttresses that are almost square in cross-section.

The east wing of the convent building is two-storey in the first section following the church, the windows of which indicate a basement that extends to the end of this wing. Two slender, slightly pointed windows with stone edging illuminate the sacristy in this section. To the north of them there is a small rectangular window. Not far below the eaves are three small rectangular windows or vents that suggest an upstairs pantry. The following section shows that it used to be two-storey, but that the two storeys were later made into a single high storey by removing the ceiling and lowering the roof by about half a storey as a flat roof that can be walked on. The edge of this horizontal roof surface was designed as a parapet made of brick masonry. The floor plan shows that this room is covered with ribbed vaults, which suggests a chapel. It is illuminated by a high, ogival, slender window. Not far below you can see the contours of a former doorway in the masonry, which was covered by a flat segmental arch. Projecting stone at the lower end of the former door suggests a platform with a staircase through which one could get into the room, possibly once the eastern entrance to the monastery. The masonry of the first wall section is a mixture of field stones and flat bricks, which increase sharply towards the top. Here the brick layers reappear, which are about a meter apart. In the second section, the bricks are concentrated around the window opening and around the former door opening. As an extension of the two room dividing walls, there are strong buttresses, which are stepped on the front side and whose upper sides are steeply sloping. They are also made of masonry, mixed with broken stone and bricks.

The second section is followed by the last section, completely covered with a single-story pent roof, made up of two smaller rooms. The first room is now the reception room for visitors. Today's front door and two small rectangular windows are left open in the outer wall. The door is reached via a ten-step staircase, the platform of which is covered by a monopitch roof that is open on all sides. The last closed room on the east side contains a staircase to the basement, which today contains museum rooms.

The west wing of the convent rooms can hardly be seen and also cannot be photographed. Its outer walls can only be roughly described using the floor plan. The first room, which reached almost half of this wing, was probably the chapter house and is lit by three very slender, arched windows. The space barely half as long on the floor above, possibly part of the former dormitory , is now illuminated by a similar window. On the ground floor there is a connecting room with an access door also from the outside. This is followed by a larger room that may have been used once as a division. Two windows illuminate him.

Interior

cathedral

The cathedral essentially consists of a spacious nave , the east end of which is closed by a staggered choir head and the west end of which is closed by a narthex , and which does not require a transept. The existing irregularities in the constructions and decorations indicate that the construction progress has been interrupted several times. The church was not built in one go, but you can see the intentions of various builders or architects from its construction and decoration.

Longhouse

The nave stands on an elongated, rectangular three-aisled basilica floor plan, which is divided into six almost equally wide bays. The central nave is almost twice as wide as each of the two side aisles. The central nave is about one and a half times as high as today's side aisles. Thanks to its great height, the central nave has very nice proportions. It is no longer exposed directly today. Its eastern vaults are slightly sharpened semicircular barrels in cross-section, while the adjoining ones are increasingly sharpened to the west. The yoke division is done by rectangular belt arches in cross-section, some of which stand on angular single- or double-tiered pillars with a cross-shaped plan, but also on those with upstream semicircular services. The last can be found in the older two eastern arcades, on all four pillars. The services are crowned by carved capitals. The next younger pillars to the west have only sharp-edged steps. The not exactly vertical alignment of the pillars and services on the central nave side is barely visible. Rather, they tend to incline slightly outwards towards the top. This is a construction principle often used in Romanesque Roussillon.

The irregularities of the pillars indicate that, according to the first building plan (around 1040), they should initially have groin vaults in the side aisles and a wooden roof truss in the main nave. The central nave received daylight directly through windows, the contours of which can still be seen in the south aisle above the arcades to the central nave.

Even in the western area of the structure, the pillars do not correspond with their belt arches. The latter have only one belt bow without gradations. On the other hand, the gradations of the pillars can also accommodate graded arches. With some pillars the gradations are lost at the top of the vault. In archaeological studies of the cathedral it was found that there is a single belt arch in the central nave, which corresponds to the original gradation of the pillars in this section of the structure, namely with double arching. It is located above the organ gallery between yoke 1 and the westwork. The arch field consists of masonry in which “right-angled cavities are assigned symmetrically to the arch axis along a gently sloping line. These cavities can only be the support of the beams that were stretched from one belt arch to the next and supported the roof. We are therefore dealing with a shield arch here. ”So the ceiling in its western section was not a simple flat wooden ceiling, as in the east, but a roof truss resting on masonry shield arches.

When it was decided to cover the nave with stone vaults, these arches of the nave had to be removed and the walls above the side arcades, which until then had only been simply stepped. The builder felt compelled to create a further somewhat wider arched step, which, however, was not concentric to the two existing ones. The smoothly plastered vault was extended over the two eastern bays 5 and 6 and their side arcades were reinforced by a third arc, which runs concentrically to the older arches. These outer sharp-edged arcade arches stand on second setbacks that are slightly wider than the setbacks in the arch area. The arch approaches are marked with short fighter profiles. The arch approaches of the central nave arcades and the barrel vault are a good bit higher and are marked by a profiled cantilever cornice.

In order to transmit the thrust of the main vault, smoothly plastered half-barrel vaults were erected over the previously significantly lower side aisles, and some barrel vaults with stilts on the inside, which supported themselves against the partition walls above the windows of the central nave, which had become superfluous. For these new vaults, reinforcements of the aisle outer walls were necessary, in the form of a round-arched, partly also slightly sharpened blind arch that runs through all yokes. Today these only exist in the north aisle, as the outer wall of the south aisle has disappeared with the addition of the Gothic chapels and the blind arches have become open arcades that transfer their loads into the transverse walls of the chapels. The arches are only marked in the chapel in front of the 6th yoke with spider profiles. The vaults of the side aisles are divided by arched arcades. Between their wedge arches and the half shield arches of the vaults, smooth plastered half shields have been created, partly also half one-hip stilted shields. The aisle arcades make their vault heights appear significantly lower than they are on the side of the partition. Their arch approaches, both at the same height, are marked by weak fighter profiles. The southern ends of the wedge arches push behind the inner wall reinforcements, in which the former pillars also disappear. The pillars and arches of the partition wall to the ship have simple sharp-edged setbacks on the sides of the aisles, and their arch approaches are marked with strong transom profiles. The two eastern pairs of pillars also have services towards the aisle.

Even if this analysis is quite technical, it does not present the peculiarities of the church of Elne completely. For example, the penultimate pillar on the north side of the main nave is the only one in the lower half to have a complicated cross-section, made up of several setbacks and without the semicircular service on the ship side. A kind of combat frieze surrounds the pillar about halfway up. This deviation is explained by a subsequent repair and reinforcement of the pillar foundation before the vaults are laid.

The south aisle opens up through six arcades into the Gothic chapels, which were built one after the other from the end of the 13th to the middle of the 15th century and at different epochs. All chapels have a rectangular floor plan and are covered by ribbed vaults and directly lit through different windows. The room in front of the 3rd yoke is not a chapel room, but a connecting room to the south portal. He and the last two chapels were also built around the same time and their vaults have prismatic cross ribs that unite in a heavy keystone.

The window and door openings are each aligned with the chapel axes. The chapel in front of yoke 6 is illuminated by a circular ox-eye and the next two 5 and 4 by a relatively small, slightly ogival window each, the one in the 4th yoke is slightly higher than the previous one. Above the arched, double-winged portal in yoke 3 there is a very small arched window. Another slim, rectangular window opens not far below the vault. In the south walls of the last two chapels of yokes 2 and 1 there is a relatively large ogival window with Gothic tracery, the height of which extends almost over the upper half of the wall. The arches of their pointed arches run in a straight line on the inside and thus form the legs of isosceles triangles.

In the first chapel in front of the 6th yoke, which is dedicated to Bishop Raimund Costa (1289-1310), his tomb in the form of a sarcophagus with a roof-shaped cover rests on two massive cantilever consoles on the east wall, the side wall of which is decorated with a sculpture of the bishop and prelate is decorated. The figure is shown in a “standing” position, facing the viewer, and gives the gesture of blessing with the right hand. He is dressed in his regalia, and his head is covered with a bishop's cap. The figure seems to have stepped out of a portal that is covered by an architecture consisting of a clover leaf arch in a pointed arch. This attitude can be found in many contemporary representations. Another tombstone in this chapel is that of his brother Petrus Costa, who died on August 13, 1320. The chapel of the 5th yoke was built at the instigation and at the expense of the beneficiary of the cathedral Gilles Batlle, who is buried here. In this chapel there is a reclining figure of Jesus Christ removed from the cross. The chapel of the 4th yoke is the St Michaels chapel. In this a wonderful Gothic altarpiece from the 14th and 15th centuries in Catalan Gothic is shown, which tells in his paintings about the work of St. Michael.

In the north aisle on the north wall in yoke 3 hangs a large wooden cross with the tools of the Passion, also called the Arma-Christi cross .

These are, for example: A third hand on the upper longitudinal bar symbolizes the keeping hand of God the Father; Hyssop with a sponge on it; Crown of thorns ; Purple skirt; Mortuary shirt; Hammer; Pliers, three dice; Pieces of silver of Judas; The jug of Pilate's hand washing; Veronica's handkerchief ; Lance; Bundle of rods; Chalice; Ladder and others.

Choir head

The choir head is a triple relay choir. The three apses are preceded by short barrel-vaulted choir bays the width of the respective nave. Their altitudes remain well below those of their ships. The barrel vaults over the yokes in front of the apsidioles are half as short as the choir yoke. In the main nave, a crescent-shaped plastered surface of the east wall of the ship rises above the edge of the choir bay arch made of wedge stones . At the very top, under the crown of the vault, a small circular ox-eye is embedded in this wall. Above the wedge arches of the even shorter yokes in front of the lateral apsidioles, the east wall takes on the shape of half shields, in each of which a significantly larger circular ox eye is cut out, with greatly expanded walls.

The choir apse and the two apsidioles flanking it stand on semicircular floor plans, the widths of which are significantly narrower than the choir bays. In the choir apse, the lateral wall offset runs roughly the same width around the entire Keilstein arch. In the apsidioles, the offset in the area of the Keilstein arch becomes somewhat wider. The curved and smoothly plastered outer wall merges into the semi-dome-shaped dome without a break. A small arched window with flared walls is cut out in the apex of this wall. In the choir apse, the curved outer wall made of natural stone exposed masonry is separated from the smoothly plastered semi-dome-shaped dome by a circumferential cantilever cornice, the height of which roughly corresponds to that of the side arcades. In the outer wall of the choir apse, three medium-sized, slender and round-arched windows are cut out, with walls widened inwards. They were enlarged in the 19th century. The central arched windows in the apsidioles are significantly smaller.

The plate of the altar, erected in 1069 at the instigation of Bishop Raimund, Count Gauzfred von Roussillon and his wife Azalaïs, has been preserved. It belongs to a series of altar plates from the Narbonne school, which are characterized by profiled strips with a wide frame band, which consists of semicircular, inwardly opening passes with simple floral ornaments with three petals cut into the spandrels. A Latin inscription in large capital letters is engraved on the smooth inner surface. Overall, it is a rather modest work and still lags far behind the most beautiful examples in this series, namely the altars by Gerona and Rodez. When the canons erected the baroque canopy in 1721, based on the example of the Paris churches of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Val-de-Grâce, they used the above-mentioned altar panel from the 11th century as the front of the new altar. The two marble slabs, on which the circumstances of the erection of the former altar were described, served as side walls. A long, unadorned altar plate was used as the new canteen , but several names were engraved on it, such as Miro and Gerbert. The tabletop with the engravings rested on a Roman gravestone made of Pyrenees marble, while the Romanesque altar panel and the two inscription plates were made of Carrara marble. The tombstone was turned upside down and equipped with a niche for relics. These were kept in a gold-plated silver reliquary from the 14th century, which itself was put back in a wooden box with inscriptions. However, this crumbled to dust when it was discovered.

The original altar table from the 11th century was separated from the baroque canopy after the middle of the 20th century and placed a little in front of it on the upturned antique tombstone as before.

Westwork with narthex and organ gallery

In the west, in front of the first bay of the nave, the narthex stands on a ground plan similar to a nave bay , above which the mighty westwork with the two towers rises. In the area of the central nave, the narthex is two-storeyed together with the first yoke of the nave and in the second forms the organ gallery, which is supported by two ribbed vaults. Their bottom is about halfway up the main nave. The round arch of the central nave arcade between yoke 1 and 2 is well below the height of the other yoke-dividing belt arches. A sickle-shaped piece of wall is inserted between its wedge arch and the vault. The eastern gallery wall butts laterally behind the ship-side pillars against the western pillar section and is closed on the underside by the semicircular arch of the ribbed vault. The organ towering up on the eastern edge of the gallery protrudes a little over this edge in the middle area. The parapets adjoining the organ on both sides are open wrought iron latticework. The space behind the organ is illuminated by the large window in the middle of the facade. In the northern arm of the narthex is a baptistery, which is covered by an ogival cross-ribbed vault. In the center is a large stone baptismal font.

Capitals in the nave

The construction of the vaults did not result in any changes to the pillars in their lower part, with the exception of the one already mentioned on the left side of the nave between yokes 5 and 6. The former belt arches in the side aisles could also be preserved, as the old groin vaults compared to today's half tons were replaced. They only got elevations from half the shields. The capitals of the eastern pillars also remained in place. Georges Gaillard demonstrated their great importance for the understanding of sculptures in Roussillon around the middle of the 11th century. In addition to archaisms, one can recognize shapes on them that were to be used by the sculptors of the following century.

By and large, the capital retained the layout of the classic composite capital , but was shortened by a number of times. As a result, the cup of capital was flattened so much that it often looks like a truncated cone that widens towards the top. Only in one case has the lower part been lengthened and has the shape of a cylinder, which seems to continue the column. The sculptor's uncertainty is evident in the choice of shaft rings . Some capitals do not have any, others are voluminous. Sometimes in the form of a cord, sometimes adorned with small pearls.

The decor moved away from the ancient tradition. The acanthus leaf , even if it was only stylized, disappeared at that time and was replaced by petals that were either executed using the drilling technique or in bas-relief or distributed a little unsystematically. But there are also palmettes enclosed in hearts . On a strongly structured capital, the artist hung pine cones under the corner volutes and showed tendrils on the central console stone. Stems of palmettes emerge from the mouth of a human mask below. Further down, palmettes surround the lower part of the capital. Such a work of art can be placed among the forerunners of the great Romanesque sculptures of the Languedoc, which appeared about twenty years later.

Elsewhere, a small figure appears amid the foliage and marks the central axis of the composition. With her hands raised, she grasps the tendrils of the center console. The voluminous protrusions on the corners on which the volutes are engraved have the very distinct shape of mouths in which teeth can be distinguished. There you can witness the incipient Romanesque metamorphosis : the structural forms bring an independent animal world to life, which owes nothing to the God-created world.

The same phenomenon can be seen in another capital covered with a kind of wickerwork. In Elne, as in Sant Pere de Roda, wickerwork contributes to the decoration to the same extent as foliage, flowers and palmettes.

The floral elements, the wickerwork and the intertwined circles can also decorate the fighter panels, where they run alongside scroll friezes, a row of small teeth or a simple cartridge that is wrongly called the “Carolingian cartridge”.

The rather mediocre capitals over the services of the central nave date from the time the vault was built in the 12th or even the 13th century.

Convention rooms with cloister

The only remaining convent rooms on the ground floor flank the almost square, slightly diamond-shaped cloister on the north side of the cathedral in two wings in the east and west. On the upper floor of the two wings, only the first convent rooms, which are directly connected to the north aisle, have been preserved. The room in the east wing was probably a ventilated storage room and that in the west wing was part of the dormitory.

The convent rooms on the ground floor, with the exception of the sacristy, are accessed from the cloister, but also had entrance portals on the outside. The first room in the east wing is the sacristy, which is accessed directly from the church. It is covered by a barrel vault, which is divided by three belt arches and exposed from the east by two arched windows. An additional small window and a wall pillar indicate that the northern quarter of the sacristy was once partitioned off.

The adjoining almost square room is now a chapel covered with two high groin vaults, which is lit from a pointed arched window and can only be entered from the sacristy. This room used to be a spacious reception room with a large portal in the east wall, the contours of which can still be seen on the outside. Ashlar cantilevered at the door sill indicate that there was a platform in front of the portal, from which a ten-step staircase led down to the site, just like a modern staircase next door today. This room was probably originally the same height as the neighboring rooms and had a connecting door to the cloister and also the door to the sacristy that is still preserved today.

The next room, today's visitor reception room, originally had a different meaning. In any case, he was missing the front door and the flight of stairs leading to it. He has received the door to the cloister, as well as the door to the spiral staircase in its northwest corner, which previously led to the upper floor of the convent rooms.

The next room, which closes the wing, is his smallest. It can be entered directly from the cloister via a round arched door and contains a straight staircase that leads down to the basement, where today the rooms of the historical and archaeological museum can be found, which presumably have the same floor plan as the rooms on the ground floor above. The largest hall of these rooms in the basement was the former Laurentiuskapelle.

The first room in the west wing is the largest of the convent rooms and is in all likelihood the chapter house of the monastery. It stands on the plan of an elongated rectangle. The vault is transversely divided into three sections by two belt arches; the first is a little wider than the other two. To do this, it is divided once more in the longitudinal direction of the room with a slimmer belt arch. The resulting fields are filled with four ribbed vaults. The room is lit from the west through three slender, arched windows with widened walls. It is accessed from the cloister almost in the middle of the length of the room. A second door opens in the north wall. One misses the openings to the cloister, which are common in chapter rooms, and consist of an unlocked door and at least two double arcatures.

Behind this is a narrow room, which has a door on each of the four sides: in the west an entrance portal, in the east a door to the cloister and on the other two sides a door to the adjoining rooms. It is possible that there was also a staircase leading to the upper floor.

This is followed by a rather large room, which was created once by merging two smaller rooms that were built at different times. The older and narrower section of the room is covered by a ribbed vault, similar to the one in the chapter house, and is lit through a window like there. The second northern and certainly younger section of the room has slimmer outer walls all around and is lit by a smaller window. Its ceiling is probably not a vault.

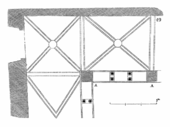

The cloister is the center of the convent tracts and is enclosed by them and the cathedral. Its interior consists of the four cloister galleries, each with four bays. When numbering the yokes, the sections in the cloister corners are not taken into account. The west and east gallery is about 3.30 meters wide, the north 3.00 and the south 2.80 meters.

See also cross-section and floor plan, graphics by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1856).

The ribbed vaults of the cloister galleries do not date from the same epochs. In the west gallery from the second yoke and in the one in the north, the rib profiles have their full depth starting from the upper edge of their cantilevered support brackets and reaching up to the keystones that are carved out of the vault there. In the other galleries, the ribs begin at the bottom of the vaulted shell and gradually emerge from it. There, protruding console stones would make no sense and are instead replaced by carved marble panels, solely with an ornamental function. The decoration of the keystones is applied there on a kind of round heraldic shield.

Jean-Auguste Brutails based himself on these observations and summarized the order in which the individual vault sections were built as follows: The oldest - and the only Romanesque - south gallery was originally covered over its entire length with a simple wooden beam ceiling. Then they began to vault the western and northern gallery with the cross ribs (described above). But when you got to the east wing, this vault was already out of date. It was replaced by a more modern cross rib system, which was then also used in the south gallery and replaced the old wooden beam ceiling.

If one examines the capitals of the gallery fittings more closely, a chronology can also be drawn up for their sculpture, which exactly confirms the chronological sequence for the creation of the vaults.

In the walls of the cloister galleries, the following openings are made on the outside:

- In the south gallery, opposite to the west, the two-winged pointed arched north portal opens into the cathedral, which is surrounded by numerous graduated archivolts. At the other end of this gallery there was a second entrance to the church, a round-arched single-wing door that was bricked up on the cloister side, but of which a wall niche remained in the side aisle of the church.

- In the west gallery there are two such doors to the convent rooms, namely in the 2nd and 4th yoke of the gallery.

- In the north gallery, two large ogival windows are left open, in the western yoke and one three yoke further to the east. Both are decorated with Gothic tracery.

- In the east gallery there are two doors as in the west gallery, one each in the two northern bays, to the stairwell and to the visitor entrance.

In the south gallery there are two large grave slabs made of white marble, which are set vertically into the walls at the ends of the gallery. Both are works by the sculptor Raimund von Bianya , who signed them himself. The grave slab at the west end originally belonged to the cloister of Elne and shows a standing bishop with his hands folded. He is dressed in his bishop's robe. He wears an alb with tight sleeves and a chasuble turned up on his arms . The Amikt forms a kind of beaded collar around the neck . The ends of the stole reach down to the feet on both sides, the maniple hangs over his left forearm. His head wears a miter in the form of a centrally indented cap with a narrow band around the forehead, which is knotted in the neck and the ends of which, the fanons (shawl), fall freely at the sides. This headgear is the so-called "horned miter". In the 13th century, the shape of the bishop's hat changed. The artist cleverly used the indentation of the miter to place the hand of God in it. In addition, he placed a hovering angel on each side of his torso, waving a censer with one hand. They seem to be supporting the bishop's head with the other hand, which is supposed to mean that they are taking up his soul.

The archaeologist and art historian Pierre Ponisch suggested to see the bishop of Elne Raimund von Villalonge (1211-1216) in this representation, while Bernard Alart equated him with another Raimund, whose episcopate ended around 1201/02. The same historian suggested the following reading for the inscription engraved to the left of the figure: R (AYMVNDVS) F (ECIT) HEC OPERA DE BIA (NY) A , which means: Raimund von Bianya created this work.

The other tombstone at the east end of the gallery comes from the priory of Owl (Pyrénées-Orientales). This was a founding of the Cistercian Sisters and belonged to the Catalan Abbey of Poblet, whose existence has been documented since 1172. In 1363 the community was moved to Perpignan, and in 1576 there were only three nuns left there who were then sent to Spanish monasteries. The priory was then taken over by Cistercian monks who stayed until the revolution.

There are two inscriptions on the tombstone. One reads without difficulty and says the name of the deceased “F. du Soler ”, and his date of death with“ the 16th calendars 1203 ”. (In another source it is called "Ferran del Soler"). The other inscription is more puzzling and could be translated something like: "Raymond von Bianya created me, and I will be a statue".

This bishop takes a very similar posture to the previous one, with his hands crossed on his chest. His face surprises with its realistic expression, which is particularly evoked by the two lively eyes under long lids. This bishop also wears a long alb with a cloak thrown over it. It is held together by a clasp at the neck. The two angels, hovering to the side of his head, wave an incense holder with one hand, while the other hand spreads it out behind his head, with which they receive his soul in order to carry it to heaven. They are obviously designed on the model of the other grave plate, but have significantly more space to spread their wings. Here, too, the hand of God protrudes from behind his head, which does not have a miter, and offers the gesture of blessing.

The two tombstones present a new way of depicting garments, as can also be found on the capital with creation and the fall of man. Every piece of clothing - whether alba, coat or chasuble, even the stole - is strewn with numerous small parallel folds, which are divided into groups by deeper folds. They rarely run vertically, but rather form a network of obliquely arranged lines that converge towards the center of the body and diverge towards the outside. The variety of overlaps is impressive; the small wrinkles look almost like threads. The legs look almost as if they were wrapped in bandages.

This rather complicated, at the same time logical fold formation can also be found in the last quarter of the 12th and the beginning of the 13th century in the Italian Bernedetto Antelami, the great sculptor from Parma. Only with him, who was already developing towards Gothic, there was more simplicity and objectivity than with Raimund von Bianya, in whom a " mannerism " peculiar to the late Romanesque style became independent. However, both artists only followed the already existing Romanesque models when using these wrapped draperies , which are criss-crossed by innumerable folds . This antiquing tendency already had isolated forerunners earlier, as can be seen in Italian works of art of the pulpit type in the cathedral of Pisa.

The influence of antiquity on Raimund von Bianya is so strong that one was uncertain about the attribution of a small half-relief (29 × 19 cm) set into the wall of the south gallery. In the center sits an angel with large outspread wings on a rectangular stone over which a blanket is spread. It is the rock mentioned in the Gospel that was rolled away from Christ's tomb and is still venerated in Jerusalem today. The angel raises his left hand, in his right he holds a scepter with a lily. To the left and right of him stand Peter and the veiled Mary Magdalene, whose posture expresses deep pain. This is an incomplete account of the resurrection of Christ. John (20, 1-10) and Luke (24, 1-8) report how Mary from Magdala and Peter came to the empty tomb. Marcel Durliat believes he can ascribe the sculpture to Raimund von Bianya. A. Frolow has given reasons for dating to late antiquity or the early Middle Ages.

The three so-called "Aquitanic sarcophagi" that were found in the area date from the Visigothic period (6th to 7th centuries). The bas-relief on one of its long sides shows lavish, carefully crafted plant decoration, interspersed with Christological motifs that had replaced the late antique-early Christian tradition of the Arles school. The scene is divided into three equal fields with four pillars. Three large, curling tendrils spread out symmetrically in the fields, which spring out from leaf fans and a calyx and carry vine leaves, grapes, flowers and palmettes.

Missing convent rooms

Even if one thinks of the missing rooms on the upper floor, one must assume that the rooms of the chapter presented here by at least 24 canons plus those of the bishop and his confidants and servants are absolutely insufficient.

In addition to the above-mentioned rooms, a closed living area of a community of monks includes: cloister, chapter house, sacristy, dormitory (on the upper floor), storage rooms (cellar and upper floor), but also: refectory , kitchen , warming room ( calefactorium ), speaking room ( parlatorium ) , Fraterie , manor house, infirmary, lay refectory, washrooms, toilets and also the bishop's apartment.

The known sources do not provide any information about the former existence of such rooms. It would be quite conceivable if a north wing of the refectory had also existed in the north gallery. On the other hand, it is also known that such areas are detached from the main structure of the monastery, such as the episcopal monastery of St-Pierre-et-St-Paul de Maguelone .

Column and pillar sculpture in the cloister galleries

If you walk through the north portal of the cathedral to the cloister, you will experience a surprise. From a closed, semi-dark room, you get into radiant light, which is enhanced by the patina of gold-colored marble.

The canons must once have had this feast of the eyes in mind when they built the wonderful framework for their community life. This is confirmed in an inscription that is engraved on two sides of a pillar capital of the south gallery.

ECCE SALVTARE PERITER FRATRES HABITARE: ECCE QVAM BONVM ET QVAM IOCVNDVM (sic) HABITARE FRATRES IN VNVM.

This pious saying takes up the first verse of Psalm 133 (132), which was sung by the Canons when they received a postulant :

"Look! How good it is, how sweet, to live all together as brothers. "

The column shafts are mostly smooth without any decoration. Some columns, on the other hand, are decorated with different ornaments, mostly as bas-reliefs, such as the one consisting of ribbons with longitudinal grooves in undulating meanders over the entire height of the column, which are intertwined with one another. The empty fields are filled with rosettes, leaf fans, shamrocks and Star of David , on other pillars they remain empty. Further ornaments are a tendril with large vine leaves wound around the shaft or twisted tendrils with curved branches and leaf fans or vertically rising tendrils with large palm leaf fans. More profound is the ornament made up of wide fluting spirally twisted around the column, the edges of which are dissolved into fine grooves. They have rounded end pieces and some balls embedded in the fluting.

The pillars on the corners of the cloister have no sculpture.

The descriptions of the column and pillar sculptures begin with those of the south gallery, followed by the west and north galleries and end with the east gallery. In the case of the capitals of the double columns, the gallery-side and then the courtyard-side are treated first.

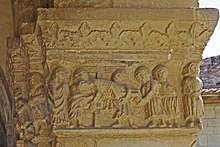

Sculpture south gallery

The decoration of the south gallery is the last evidence of the marble carving art of the 12th century in Roussillon. Around the same time, the church of Corneilla-de-Conflent was equipped, and a stylistically very similar sculptor's workshop built the gallery at Ripoll in Catalonia.

The cut of the column capitals remains very traditional. They consist of almost cube-shaped white marble blocks with gray veins and comprise three elements: the cup of capital adorned with foliage and animals, the volutes borrowed from the Corinthian capital and the abacus with double grooves on each side. In this way, three console stones are created on it, of which the middle one usually has a sculpted head. A transom with beveled edges is inserted between the beginning of the arch and the capital. The bases also have the familiar profile. They consist of two round bars that are separated from each other by a groove; claws represent the transition from the lower torus to the square base.

It starts with the first double columns and the gallery-side capital. There you can see eight griffins standing on their hind paws, two of which are adjacent to each other with their heads united at the corners. Their beaks chew the ends of their wings. The flat background of the sculpture is covered with diagonal stripes, as we know it from the galleries of Saint-Michel de Cuxa and the Prieuré de Serrabone. In contrast to these models, however, they are finely lined here, a sign of further development in the sense of an enrichment of the decor.

Towards the courtyard there is a capital with two rows of palmettes, the stems of which curve, straighten and spread out, as on some capitals in Corneilla-de-Conflent. The bevelled edges of the fighter plate are decorated with plait patterns, apart from the smooth side facing the courtyard.

On the second gallery-side capital, two lions stand on all fours with extremely high arched backs. There are also other lions that appear to be walking upright. The origins of this motif can be found in the Prieuré de Serrabone. You can see here that it could still be “reduced” without losing anything of its plastic quality.

The capital with the palmettes appears again towards the courtyard. The bevelled, slightly rounded edges of the cover plate are decorated with lush tendrils, the flowers and palmettes of which stand out in front of heart-shaped leaves that are decorated with elaborately designed pearl-like structures.

The capital of the first pillar is adorned on all sides by two rows of flowers and a row of leaf fans, which are arranged with frequent geometric regularity and carved with elegant and profound delicacy. The four petals with diagonal ribs and lobed edges enclose a raised bud. The wide beveled and slightly rounded fighter profile is adorned with a tendril ornament, made of meandering intertwined ribbons with outwardly curled branches and leaf fans in the inner spaces.

Zoomorphic and floral motifs alternate on the capitals of the second yoke . First, winged lions appear on the gallery side, facing each other at the corners. Its tail reaches between its paws and widens into flowers, its wings end in long feathers. The joints of the powerful muscular paws are carefully modeled. The shaft rings are adorned with pearls. The edges of the cover plate are decorated with quatrains.