Piece

As Stuck (from Ital. Stucco ), the plastic forming of mortars of all kinds, generally referred to plaster walls, vaults and ceilings. Since ancient times until today, stucco has been an important technique for the design of interiors and facades. Sgraffito is a special stucco technique .

The term “stucco” includes all work with mortar, from a simple facade design with cornices to large, three-dimensional wall and ceiling designs with opulent, three-dimensional forms of the Baroque and Rococo . Due to the “ban on images” in Islamic art , stucco decorations occupy an important place there.

Since the turn of the 20th century, prefabricated parts have been offered in catalogs that are mass-produced in casting molds. Stucco is made by the plasterer .

Stucco mortar

Stucco mortar is obtained by mixing aggregates (originally mainly sand, today also lightweight aggregates), water and binding agents such as sump lime , white lime and gypsum, as well as hydraulic lime and cement for external stucco . Mortar for application stucco work often contains other additives such as glue glue to influence the viscosity of the mortar or the setting behavior.

Groups of stucco work

- Plastering work: lining of internal and external wall surfaces, ceilings, vaults with mortars of various compositions. The plastering can be done directly on the masonry or the plaster base, but mostly a primer in the form of a spray grout is applied to a plaster base and is then used for further contract or application work.

- Pulling and twisting work: Using special templates , three-dimensional decorative elements such as B. rods, ribbons, profiles or pilasters several times before and finally sharply removed. This is necessary as the plaster of paris always expands until it hardens. The Ab turn takes place as well. For example, spheres, columns or balusters are turned off .

- Application work: Application stucco - elaboration of plastic stucco elements on the spot in the still soft stucco mass in a mostly quick process, which requires great craftsmanship (mainly used in the Baroque and Rococo).

-

Artificial marble work ( marble stucco , scagliola , stucco marble ): imitations of various types of marble. The profession formerly known as marbling or marbling has largely disappeared from the spectrum of plastering work, but these techniques are still sporadically mastered in the Alpine region in particular. Marbled columns and altars were made in large numbers in the Baroque and Rococo periods. Courses are also offered as part of restoration work. For anhydrite or high fired gypsum are leveling floors made that also colored encrusted have been. Another special technique is the → terrazzo .

Colored anhydrite screed, Bassum collegiate church

Colored anhydrite screed, Bassum collegiate church - Forming, casting and relocating work: production of negative forms from clay, glue, plaster, etc. a. according to a model. The individual parts cast in plaster of paris, hard plaster or cement are attached to wall and ceiling surfaces with screws or dowels, for example as cornices . Plaster figures were made in large quantities for devotional objects . Today, mineral or plastic foams are widely used.

- Plaster cut: The plaster cut is actually an artistic application of the stucco technique, which enables figurative and ornamental elaborations. It was widely used in the 1920s and 1930s ( Art Nouveau ). The actual plaster cut is done negatively: the form is cut into precast plates made of model plaster and then offset. Another, somewhat more difficult version is that an additional positive, i.e. raised cast was made from this negative form. With undercut shapes, however, this was only possible with the lost shape. When making a relief cut, the remaining areas must also be cut.

- Malstuck - Stucco lustro : a painting technique related to the fresco technique with great color luminosity , which is given a shine by smoothing with hot iron.

- Sgraffito : A special form is also Kratzputz called sgraffito . It is also counted among the stucco techniques. Sgraffito means that still moist, different colored plaster layers are scratched out. Modern graffiti have a similar effect, they are usually applied in layers, but are not stucco work, since no plastic mass is moved, but "only" colors.

Standards for the plastering and stuccoing trade are regulated in the procurement and contract regulations for construction work , Part C: General technical contract conditions for construction work (VOB / C, ATV), DIN 18350 (plastering and stucco work).

history

In the Neolithic Age , plaster of paris was already known, and thus the use of the material obtained for plastic applications was specified as "stucco". As early as 7000 BC In the city of Çatalhöyük in Asia Minor, plaster of paris was used for interior design. There are references to the use of plaster of paris among the Sumerians and Babylonians.

Egypt:

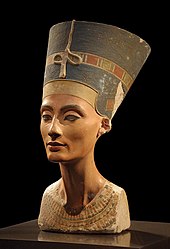

The production and use of plaster of paris was known to the Egyptians early on and it was used in a variety of ways, a famous example being the bust of Nefertiti . The stucco painted with natural pigments gives her face the fascinating charisma that inspires visitors to Museum Island today . Calcareous gypsum mortar was used to work on the Sphinx .

Antiquity:

The Minoan culture used plaster of paris and alabaster instead of marble as flooring or wall covering and as building blocks, for example in the palace of Knossos and the palace of Phaistos . The Greek historian Herodotus reports that the Ethiopians cast their dead in plaster, Theophrastus of Eresus described the production of plaster in a treatise. Around 300 BC Lysistratos had already taken off face masks. In Greece, plaster of paris was used for ornamentation on houses.

The Romans used plaster of paris for interior design. A thin layer of gypsum was also used to store fruits; gypsum (today: bentonite ) was already used for winemaking at that time. Juvenal reports on a plaster bust, Vitruvius in his "Work on Architecture" and Pliny in his "Historia Naturalis" on stucco ceilings. You already distinguish the lime stucco from the plaster stucco. Excavations, especially in Pompeii, confirmed this. In imitation of expensive types of marble, the walls were covered with colored stucco stucco lustro . Elaborate cornices emphasized the vertical structure. Stucco ceilings were common in public buildings and posh homes. Stucco decorations are preserved in the tomb of the Valerians, on the Via Latina near Rome, 2nd century AD on the vaulted ceiling in the temple of the Valerians , the tomb of the Valerians , they have been extensively restored. Magnificent stucco work has been preserved in Pompeii , today's Pompei . The Villa Adriana contains original stucco work by the Romans.

Middle Ages:

The recording and research of stucco sculpture and stucco decorations in the Middle Ages is still a relatively new topic in art history. Since the 1990s, there has been knowledge of the manufacturing technique and the polychromy of stucco in medieval sacred buildings in the Harz foreland. So here, in today's federal states of Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, a number of important medieval works of art made of stucco have been preserved, especially from the 12th and 13th centuries. Mention should be made of the Holy Grave in the collegiate church in Gernrode , the choir barriers in St. Michaelis in Hildesheim , the Liebfrauenkirche in Halberstadt and the collegiate church in Hamersleben , the west gallery of the former monastery church in Gröningen Monastery (today Berlin, State Museums, Bode Museum) , the tympanum of the Hildesheim Godehardikirche, the gable relief of the cathedral porch in Goslar or the cycle of apostles in the Ganderheim collegiate church. The large stucco floors with very individual designs, such as B. in Hildesheim Cathedral and the Helmstedt St. Ludgeri Church.

Renaissance:

In Germany, "plaster casting" had been known since at least 1473; instructions for it were printed in Nuremberg in 1696. In 1615 Scamozzi reported in his work »Architettura« (Ten Books on Architecture) about the production of a stucco mass. There was a revival in the Italian Renaissance . Walls and ceilings of churches and palaces were now covered with large stucco systems, often in close connection with wall and ceiling paintings. Famous plasterers of the Renaissance were Perino del Vaga , Fedele Casella and Scipione Casella . In the course of this revival, among other things, Germany developed its own, mostly artisanal, artificial strand, which mainly used lime stucco.

Baroque:

The craft of stuccoing experienced a particular heyday in the Baroque and Rococo , for whose lively and playful decorative elements the technique of stuccoing was well suited. While Italian plasterers initially created high-quality stucco work throughout Europe during this time, regional and sometimes supraregional master plasterers soon developed - especially in southern Germany. Their works can be found on Oberschwäbische Barockstrasse ; Together with the Wessobrunn School, they are important representatives of this art. The most famous object of this era is likely to be the honey sucker in the Birnau pilgrimage church , created by the plasterer and sculptor Joseph Anton Feuchtmayer .

In the Baroque era, stucco marble ( scagliola ) was often used for design - an elaborate method of imitating marble , which was more expensive than marble itself, but enabled larger, uniformly colored workpieces as well as particularly dramatic artistic effects of the coloring.

19th century:

During the founding period and in the era of historicism , stucco was a favorable design element in architecture. It was also widespread in Art Nouveau .

Modern:

With the onset of modernism after the First World War , stucco was almost banned from architecture. In Germany in the 1950s and 1960s, decorative stucco continued to lose importance and was often perceived as disruptive because it did not correspond to modern architectural ideas. For this reason, the stucco was removed from many old buildings, which was referred to as "façade desolation", stylistic adjustment or removal of stucco . Rich stucco ceilings were suspended , that is, a flat ceiling construction was pulled under the stucco ceiling and the stucco was often considerably damaged in the process. On the other hand, by "hiding" certain treasures were preserved that were otherwise endangered by frequent painting over (or removal).

Execution types

In addition to being made of stucco, stucco-like profiles were also made of wood and either left exposed to wood after assembly or treated with putty, spatula and paint until they could no longer be distinguished from stucco profiles made of plaster or lime. Just like the decorative profiles, which traditionally form the upper end of high-quality wooden cabinets, material-transparent wooden profiles in the upper area of walls are called crown profiles .

In the post-war period, "artificial stucco" was developed. From the 1970s in particular, stucco elements made of plastic that could be glued and painted over , mostly made of rigid polystyrene foam , were used. Today, prefabricated stucco elements made of mineral casting compounds with lightweight aggregates or made of milled mineral foam are also offered.

Mayan art

In Mayan art - especially on the Yucatán peninsula - both simple plastering made of plaster and plastic figurative stucco work on external and internal walls play an important role (→ web links ). Both in the surface and sculptural stucco work (reliefs and sculptures) were always painted in color, with paint residues only in the rarest cases (e.g. in overbuilding). Mile -long processional streets ( sacbes ) were also covered with layers of plaster that were centimeters thick. Since limestone had to be burned to produce gypsum , large areas of forest were cut down, which - among other factors - may have had such negative effects that the entire ecosystem and thus the advanced cultures of the Maya civilizations collapsed around 800 AD.

Set structures

For film sets , stage sets , ornaments in model construction or for decorations , plaster of paris is used in conjunction with sackcloth in order to be able to quickly create large areas. The use of the "staff" (derived from dressing up) named material goes back to Alexander Dessachy, who patented it on December 2, 1861. The mass mixed with a little cement, glycerin, dextrin and water can be poured into molds and reinforced with burlap as needed. In France, the profession of Ornametiste Staffeur developed from this . However, supporting materials were used earlier, such as mats made of reed or wooden strips. Later, galvanized wire mesh or Rabitz was used , today also glass fiber mesh .

museum

- The only museum in Germany that deals exclusively with stucco is the private Small Stucco Museum in Freiburg im Breisgau .

- Gypsum mining in the 18th and 19th centuries Century is shown in the plaster museum Schleitheim .

literature

- Barbara Rinn-Kupka: Stuck in Germany. From early history to the present Verlag Schnell und Steiner, Regensburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-7954-3133-4 .

- Edmund Heusinger von Waldegg : The plaster , Leipzig 1906.

- GI Astachow, WP Ivanov: plastering and stucco work. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1956.

- Geoffrey Beard: Stuck. The development of plastic decoration. Edition Atlantis, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7611-0723-4 .

- Paul Binder, Fritz Schaumann, Meinrad Haas, Karl Läpple: plasterer manual. The plaster primer. 3. Edition. Schäfer, Hanover around 1955. Reprint: 1985, ISBN 3-88746-087-1 .

- Alfred Bonhagen: The plasterer and plasterer. Voigt, Leipzig 1914. Reprint: Reprint-Verlag, Leipzig 2003, ISBN 3-8262-0211-2 .

- German stucco trade association in the central association of the German building trade (Hrsg.): Stucco - plaster - drywall. Specialist book for training and further education in the plastering trade. 2nd Edition. Müller, Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-481-00316-1 .

- Martin Hoernes (Ed.), High and late medieval stucco: material, technology, style, restoration; Colloquium of the Graduate School "Art History - Building Research - Monument Preservation" of the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg and the Technical University of Berlin, Bamberg 16. – 18. March 2000, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, 2002.

- Matthias Exner (Ed.): Stucco of the early and high Middle Ages, history, technology, conservation, a conference of the German National Committee of ICOMOS and the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim , 15. – 18. June 1995, ICOMOS booklets of the German National Committee 19, Munich 1996. ISBN 3-87490-660-4 .

- Specialist group stucco-plaster-drywall in the specialist group Bau Berlin and Brandenburg: stucco marble and stucco lustro. New building in traditional techniques. Knaak, Berlin 2001.

- Siegfried Leixner, Adolf Raddatz: The plasterer. Handbook for the trade. 4th edition. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-421-03096-0 .

- Lexikon der Kunst, Vol. 7, Leipzig, EA Seemann Verlag, 1994, Lexicon article “Stuck”, p. 106 ff.

- Katharina Medici Mall: Lorenz Schmid. A Wessobrunn altar builder and plasterer. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1975, ISBN 3-7995-5021-6 . (Lake Constance Library, Vol. 21.)

- Jürgen Pursche (ed.), Stucco from the 17th and 18th centuries. History - Technology - Preservation, results of an international symposium of the German National Committee of ICOMOS in cooperation with the Bavarian Administration of State Palaces, Gardens and Lakes, Würzburg, 4. – 6. December 2008; ICOMOS booklets of the German National Committee 50, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-930388-12-7 .

- Peter Vierl: Plaster and stucco. Manufacture, restore. 2nd Edition. Callwey, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7667-0873-2 .

- Horst Wilcke: Stucco and plaster work. 8th edition. Verlag für Bauwesen, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-345-00152-7 .

- Otto Beck, Ingeborg Maria Buck, Oberschwäbische Barockstrasse , A travel companion for art lovers, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Vol. 148, 1987, ISBN 3-7954-0670-6 .

- Hugo Karl Mario Schnell, The Baierische Barock 1936.

- Wilhelm Messerer, Children Without Age - Putti in Art of the Baroque Period , Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 1962.

- Barbara Rinn: Italian plasterers between the Elbe and the Baltic Sea. Stucco decoration of the late baroque in Northern Germany and Denmark. Publishing house Ludwig, Kiel 1999.

Web links

- Color slide archive for wall and ceiling painting, stucco decorations and room furnishings (photo library of the Central Institute for Art History Munich)

- Cultural history of stucco at Monumente online, magazine of the German Foundation for Monument Protection

- Video about stucco repairs in old buildings

- Ancient stucco technique

- Stucco in Mayan art - photo + info

- Stucco in Mayan art - photo + info

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kühn, Hermann, What is stucco? Types - Composition - History, in: Exner (Hrsg.), Stuck of the early and high Middle Ages. History, technology, conservation. A meeting of the German National Committee of ICOMOS and the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim in Hildesheim, June 15-17, 1995, ICOMOS booklets of the German National Committee 19, Munich 1996

- ↑ Lexikon der Kunst, Seemann, Leipzig, Vol. 7, 1994, Stuck, p. 106.

- ↑ https://www.baufachinformation.de/denkmalpflege/Abnahme-von-Deckenstuckaturen-mit-Verlorenform-und-Quetschform/1988067120449

- ^ Karl Lade, Adolf Winkler, Stuck Putz Rabitz , 1952, p. 207, black and white photo

- ↑ Martin Hoernes (ed.), High and late medieval stucco: material, technology, style, restoration; Colloquium of the Graduate School "Art History - Building Research - Monument Preservation" of the Otto Friedrich University of Bamberg and the Technical University of Berlin, Bamberg 16. – 18. March 2000, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, 2002.

- ↑ Matthias Exner (Ed.), Stucco of the early and high Middle Ages, history, technology, conservation, a conference of the German National Committee of ICOMOS and the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim, 15. – 18. June 1995, ICOMOS booklets of the German National Committee 19, Munich 1996.

- ^ Barbara Rinn-Kupka: Stuck in Germany. From early history to the present, Regensburg 2018, p. 105

- ^ Barbara Rinn-Kupka: Stuck in Germany. From early history to the present, Regensburg 2018, pp. 114ff

- ↑ Claudia Füßler: Freiburg: Prelude: Tour of the Baden trade fair: From love cheese to fish praline , Badische Zeitung from September 14, 2009, accessed on July 12, 2011