Tauberbischofsheim Altarpiece

The so-called Tauberbischofsheim Altar (formerly also known as the Karlsruher Altar or Karlsruhe Tafeln ) is a late work by the painter Mathis Gothart Nithart, known as Matthias Grünewald, which was probably created between 1523 and 1525 . The first written evidence of the work comes from the 18th century, when the altar was still in the town church of St. Martin in Tauberbischofsheim . Its original installation site and its client cannot be proven with certainty, but an original development for the city church is considered possible and the client is assumed to be in the vicinity of the Mainz cathedral chapter and the clerics associated with it in Tauberbischofsheim. The altar's panels, which are now displayed separately - depicting the crucifixion of Christ and Christ carrying the cross - were originally painted as a bypass altar retable on two sides of a 196 cm high and 152 cm wide wooden panel. It is unclear whether the work was conceived as the middle section of a winged altar . In order to enable the usual installation in a picture gallery , the panel was split in 1883 during the first restoration work.

The work has been owned by the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe since 1900 .

The Tauberbischofsheim Altar is not only considered to be outstanding in Grünewald's work in terms of painting technique. The clarity of the formal structure and the renunciation of iconographic symbols customary at the time in favor of an expressive representation that emphasized the individual gestures make this painting protrude far beyond the tradition of the late Middle Ages .

Origin and history

Dating and client

In Grünewald research, the work is consistently dated to the years after 1520 on the basis of stylistic studies. In connection with the limited amount of biographical information, it was probably created around 1523/24. The altar is therefore - despite all the uncertainty in the dating of the so-called Aschaffenburg Lamentation - the last surviving work by Grünewald, who died in Halle / Saale in 1528 . It was at that time in the Grünewald 1515-1526 as Electoral Mainz court painter in the service of the Archbishop of Mainz Albrecht of Brandenburg stood and 1520, lost three altars for the Mainz Cathedral created. The Erasmus and Mauritius panels (today in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich) for the collegiate church in Halle / S are made during the same creative period . and the mentioned Lamentation of Christ in the Aschaffenburg collegiate church .

The work is described for the first time in an inventory of the diocese of Mainz around 1768, which also describes all the altars of the Tauberbischofsheimer Martinskirche, which were redesigned in the baroque style around 1761. In the second volume of this Dioecesis Moguntia , Johann Sebastian Severus (1716–1779) wrote about a cross altar (an altar for special veneration of the cross) in Tauberbischofsheim:

"S. Crucis pariter noviter vestitum, in quo elegans pictura artificiis Alberti Dürer manu facta, Christu (m) es (t) una parte Bajulum, et in altera parte pendulum crucis repraesentans. "

"Holy Cross, redesigned in the same way, inside a tasteful picture of Albrecht Dürer's hand painted with skill, depicting Christ on one side as a porter, on the other side hanging on the cross."

The fact that the altarpiece is attributed to Albrecht Dürer, the exemplary representative of German Renaissance painting , is evidence of how quickly Grünewald's work and person were forgotten and what high quality the altarpiece was granted. The cross altar described here as S. Crucis was already listed by the Franciscan Johannes Stravius in a letter about the nine altars of the church in 1664 to the historian Johannes Gamans . It is unclear whether this cross altar can already be identified with Grünewald's work. A cross altar was mentioned earlier because the pastor Friedrich Virenkorn financed a foundation (benefice) for a new cross altar in St. Martin's Church in 1505 and expanded it in 1515. Virus grain was therefore often assumed to be the founder of the picture. The Archbishop of Mainz Albrecht von Brandenburg - one of Grünewald's most important clients - granted this cross altar a special canonical status in 1517. A transfer of the work from another church - for example the Mainz Cathedral itself, in which Grünewald made altar frescos around 1520 - would certainly have been noted in the diocese's administrative files. It seems unusual to assume that the client was responsible for such a high-ranking work by Grünewald in Tauberbischofsheim, who was then in the service of the Mainz Cathedral Chapter and Archbishop Albrecht of Brandenburg. But Tauberbischofsheim was closely linked to the Mainz cathedral chapter. It housed the sending court for all parishes of the Taubergau , which were under the patronage right of individual Mainz canons and cathedral princes . So the client for Tauberbischofsheim can also be assumed to be in Mainz. Even if there are no clear documents about this, current research takes Tauberbischofsheim as the original installation site. The client, however, remains unclear.

Installation site in the Tauberbischofsheim town church

The Gothic town church, the three-nave basic structure of which was completed before 1448, was expanded between 1493 and 1504 by adding three side chapels to the north aisle (numbers 6, 7 and 8 in the illustration). An extension of the nave and the construction of a double chapel (9) had also been completed by 1510 . With the creation of the side chapels, the artistic design and decoration of at least four further altars became necessary; During this period of redesign, a possible original installation of the Grünewald altar can be seen.

In the description from 1768 - shortly after the baroque redesign of the church - the arrangement around 1530 can no longer be recognized. This report covers the cross altar in one of the side chapels (8) and also includes the back of the work facing the wall. This was still visible in spite of the limited space, but such an arrangement was not common for a two-sided altarpiece , the back of which also had to be clearly visible. Even before the side chapels were added, an altar of the Holy Cross is mentioned in 1494, which therefore could not have been in the side chapels. It is considered likely that Grünewald's tablet was placed on the altar at the entrance to the choir room (2). This altar seems to have been rededicated as a St. Stephen's altar before 1664 and later also contained a veil relic of Mary (veil altar ). The Stephans altar was torn down during the Baroque era in 1760 at the latest.

The installation at the choir screen raises the question of the possible conception as a typical winged altar , in which the work consequently only represents the preserved middle section of a triptych . The design as a single image, which was framed in an aedicular frame, is not atypical for the early 16th century and can also be demonstrated at the transition from the nave to the choir. In Grünewald's so-called Stuppacher Madonna , this frame has been preserved and served as a model for a possible reconstruction of the panel installation in Tauberbischofsheim. The wooden panels for such single pictures were usually primed with a chalk base and linseed oil varnish together with the frame only after they had been framed . Remnants of priming burrs can be found on the Tauberbischofsheimer altar and suggest at least one setting in a groove strip frame .

From Tauberbischofsheim to Karlsruhe

In 1873 the crucifixion, which was still in a baroque altarpiece from 1761, was photographed by the local photographer Joseph Heer and the gilder Franz Stark and further research was carried out on the origin and author. After Hans Thoma presented the photos , the art historian Oskar Eisenmann attributed the work to Grünewald in the same year. Due to the very poor state of preservation, the parish priest removed the plaque from the church in 1875 and left it to Franz Stark as compensation for the gilding work he had done.

Eisenmann, who had examined the panel in Tauberbischofsheim in 1877 and took up a position as the first director of the newly built picture gallery in Kassel , referred the German-American art collector Edward Habich to the panel. He acquired the panel from Stark in 1883 and handed it over to the Munich restorer Alois Hauser jun., Who carried out the splitting and the first securing work. Habich left the work, which now consists of two panels, to the Kassel gallery as a permanent loan . Here they aroused extraordinary public interest as the “main ornament of the old Germans of the Habich collection” , since the rediscovery of the “old German masters” and Grünewald in particular was an important trend in art reception after the establishment of the German Empire .

But the ownership structure was unclear because the panel had come into Stark's possession illegally: the city pastor was not entitled to transfer the panel as wages because it was owned by the Church of the Archdiocese of Freiburg . As a result, Habich had not legally acquired ownership. After the intervention of the Catholic Board of Trustees in Tauberbischofsheim, the tablets were brought back to Tauberbischofsheim in 1889 to be put up again in the church. Here they suffered considerably from the bad climatic conditions, so that they were finally kept in the rectory, where they continued to deteriorate. After long negotiations and the efforts of the Karlsruhe art historian Adolf von Oechelhäuser to save the panels, they were brought to the Grand Ducal Art Hall in Karlsruhe in 1899 . Its director Hans Thoma acquired the work for the Grand Duchy of Baden on June 6, 1900 with the consent of the Archbishop of Freiburg, Thomas Nörber . The purchase price of 40,000 marks was used in 1910 to demolish and rebuild the Tauberbischofsheim town church. A copy of the “Crucifixion” made by Josef Ziegler in the baroque altarpiece from 1761 has been in the new town church of St. Martin since 1926. A copy of the “Crossing” was completed in 1985 by Matthias Hickel and is in the “Tauberfränkisches Landschaftsmuseum” in the Kurmainzischen Schloss Tauberbischofsheim displayed.

Carrying the Cross

Description and composition

Grünewald chose a moment as the scene of the carrying of the cross when, according to extra-biblical tradition, Jesus falls under the weight of the cross and is driven on by the soldiers. A three-part architectural renaissance structure forms the background, which is kept in very dark brown tones, in the middle of which a columned hall in the form of a loggia or gate hall is indicated. This is followed by large archways on the right and left. Only the lighter archway on the right side, decorated with antique tendrils, reveals a hint of the crucifixion site on a hill. Above the portico, a distant domed building protrudes against the blue sky and rises above what is probably an octagonal central building . On the frieze of the pillared hall there appears - commenting and interpreting the scene - a reference to the 53rd chapter from the book of the prophet Isaiah , the so-called “ 4th God's Servant Song ” in an early German text version: “ESAIAS · 53 · ER · IS · UMB · OUR · SUND · WILL · CLAIMED " ( Isa 53 EU )

The action is concentrated in the foreground on Christ and the four soldiers who surround him, who, as in an open circle that surrounds the viewer, closely surround the fallen. Their clothes in the style of mercenaries of the 15th century is held in alternating reds and yellows, while Christ is surrounded by a large blue cape. Another platoon of soldiers is pushing up from the left, one of them on horseback, three others almost completely covered and can only be guessed through the towering, long lances . On the right edge of the picture, two lance-bearers, who are also concealed except for parts of the face, turn to the action. Of the four soldiers in the central group, the two in the back pull out to strike, one is wearing a turban , the face of the other is covered by the cross and his reaching hand protrudes emphatically. The dominant figure on the left side grabs Christ by the robe and holds a baton tightly gripped with a threatening gesture. On the right kneels - mockingly on the left leg - a soldier with a halberd in his right and a stick in his left fist. Its brutality is underlined by the picture in the profile; the ugliness of the face cites the demonic motif in medieval tradition.

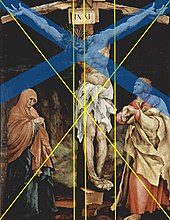

The depiction of this restless and rushed scene is based on a large diagonal composition. A diagonal follows the cross bar rising from left to right and is underlined by Jesus' posture, the halberd and the lances in the right background. A second large diagonal, crossing the first in the golden section , forms the head and posture of three soldiers in front, the face of Christ facing upwards, the lances in the left background and the profile of the rider on the edge of the picture. These two diagonals (shown in blue in the figure) together form a cross falling to the right. The geometrical center of the picture is the head of Christ, which turns upwards, towards the temple building in the background, which is also aligned with the center line. This reference to the temple of Solomon - underlined by the repetition of the blue sky in the blue robe of Christ - identifies Christ as the “New Temple” ( Mk 14.58 EU ). The background underscores these moving diagonals with a calm three-part division, both in the subdivision between archways and gate hall, the three columns of the gate hall itself and the three-tiered structure of the temple. This three-way division refers to the depiction of the crucifixion on the front of the altarpiece.

Sign language and pictorial tradition

It was pointed out that Grünewald's sign language in the Carrying of the Cross could have been inspired by an engraving by Andrea Mantegna . Albrecht Dürer had drawn this illustration of the Triton fight in 1494, so it was accessible in Germany. An entry in Dürer's diary from 1520 could support this thesis. As a result, Dürer would have “given art to 'Mathes' for 2 guilders in Aachen” when he was possibly in Aachen in the wake of Albrecht von Brandenburg for the coronation of the emperor . Accordingly, three tritons in Mantegna's copper engraving correspond to the soldiers in front carrying the cross, namely the triton on the right side with the raised arm, the scourging soldier with the concealed face, the triton standing behind and using a fish as a weapon, the soldier with the turban and finally the gesture of the Triton lifting up a skull would correspond to the dominant soldier on the left side of the picture carrying the cross. The plausible proof of this suggestion by Grünewald through models from the Italian Renaissance would be unique in his oeuvre, since in art history he is considered closed to these influences and adhered to the Gothic tradition.

But other elements of the carrying of the cross are also unusual in Grünewald's work or the pictorial tradition. In contrast to this, for example, the vertical bar of the cross carried is almost completely covered and removed from the diagonal composition. The choice of actors is also unusual, many of the people portrayed in the tradition of carrying the cross, such as Simon of Cyrene or Saint Veronica , have been left out, and Christ alone is delivered up to the soldiers. The German inscription on the columned hall in the background is also unusual for the time and often gave rise to speculation. Other inscriptions in Grünewald's works (for example in the crucifixion of the Isenheim Altarpiece ) are in Latin and in the Gothic tradition, German inscriptions are usually only emblazoned as banners and are assigned explanatory people. A comparable inscription on large-format works of the time has not survived; it was only included in the visual language in the course of the Reformation . As a description and interpretation of the entire picture, the text wants to point out a hope of salvation on the one hand and self-knowledge on the other hand legibly for everyone. The exact phrase “he was clapped for the sake of our sound” has no literal equivalent in biblical texts of the time and is to be regarded as a summing up excerpt from Isaiah chapter 53. In this sense of the commentary, Grünewald concentrates the carrying of the cross on beating, as is otherwise only common in depictions of the flagellation.

The crucifixion

Description and composition

The depiction of the crucifixion on the altar contrasts with the carrying of the cross with an emphatically calm composition. The central axis is the vertical cross stem, the body is shifted slightly to the right and twisted from this. Christ appears with his hands reaching far into the outermost corners of heaven; the wooden stake to which the cramped feet are nailed forms the lowest and furthest forward pictorial element. The pale body is pale, covered with traces of flagellation. After the prick with the lance, blood comes out of the side, the thorn-crowned head with its mouth slightly open is lowered. The darkened background, only vaguely suggestive of rocks, shows the hour of death ( Mt 27.45 EU )

Under the cross there is only Mary on the left and the disciple John on the right . Both are very contrasting in the color of the robes and the gestures; Grünewald skillfully uses the design of the robes for the psychological characterization of the people. Mary is covered with an earth-colored veil, the protruding blue undergarment quotes the robe of Christ carrying the cross, her outline is simple and takes up the rock image in the background. Her head is bowed, the veil and hands radiate an introspective, tolerant pain.

Johannes, on the other hand, looks more moved and agitated. His left foot strides forward, the pale face with red-tinged, pinching eyes is turned towards the crucified. The clasped hands rise demanding and complement the movement of the red and yellow robe. According to traditional iconography , a tear in the red undergarment on the left shoulder indicates a person in an extreme life situation. This deviation from normality is also underlined by the fact that, in contrast to the usual beardless representation, Johannes is shown with a beard. These features have long been interpreted as an indication that a preserved chalk drawing by Grünewald is very likely a preliminary study for the crucifixion of John the Tauberbischofsheim.

What is remarkable about this representation is the way the light is directed when looking at the individual people. While the representation of Mary suggests a light incidence from the right, in the case of Johannes a light source is to be assumed on the left. In fact, Grünewald lets the light rise from the center of the picture, symbolically anticipating the resurrection. This effect is reinforced by the bright and oversized depiction of the crucified and the beam-like arrangement of the body and arms (which now calmly form intersecting diagonals).

Position in the depictions of the Crucifixion by Grünewald

The Tauberbischofsheimer Kreuzigung is preceded by four surviving crucifixion pictures by Grünewald, which suggest a special conception of this last depiction. At first glance, the so-called “Small Crucifixion” (around 1502) and the “Basel Crucifixion” (around 1500–1508) appear very similar: the postures of Mary and John are very similar in these, although less elaborate. However, as in the crucifixion of the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–1516) in particular, other people ( Maria Magdalena , Longinus or John the Baptist ) and some allegorical elements ( Lamb of God ) are added to the scene . The reduced concept in Tauberbischofsheim to two people under the cross takes up a medieval design, contrary to the previous pictures by Grünewald and the general art-historical development around 1500. At the same time, Grünewald combines this reduction with a sophisticated imagery, balanced composition and a mature painterly quality that is based on the expressive aura of the Isenheim Crucifixion.

- The development of Grünewald's depictions of the Crucifixion

Position in liturgy and church history

The work in the liturgical context

Different liturgical functions of the front and back of the Grünewald altar can be derived from the probable location of the Grünewald altar at the transition from the nave to the choir of the Tauberbischofsheimer Stadtkirche . Why there is no representation of the resurrection or the burial on the back of the altar, but the concentration on the beaten servant of Isaiah, commented on with “for the sake of our sound” , can be explained by the liturgical practice of the time. In comparable works of art, on the back facing the choir, themes such as the Last Judgment are often depicted, which are related to the sacrament of penance . This should be due to the practice that the confessors prepared behind the altar for the sacrament. Such a liturgical practice can be seen in the depiction of the "Mass of St. Aegidius" around 1500.

The subject of the carrying of the cross and the drastic depiction of the cross wounds is a painterly response to the practice of liturgical veneration of wounds, a specific theology of the cross (Theologia crucis) , which became more common in the 15th century and which resulted from the increasing holding of crucifixion devotions at the end of the 15th century and the Emphasis on the Passion event becomes evident.

A Reformation Confession?

Grünewald's position on the Reformation theology of Martin Luther is widely discussed. The reason for this is, in particular, the Grünewald estate directory, in which “1 cleyn buchelge (little book), elucidation of the 12 articles of the Christian faith, item 27 of Lutters preaching; Another letgin ( little box ) nailed up. Item the nu testament, and sunst a lot of trucket (prints) Lutheran. ” Have found. A direct commitment to reforming Grünewald at the end of his life may not be easy to deduce from this. However, Grünewald seems to be part of what is now called a “Reformation public”.

The core statement of the Tauberbischofsheimer cross-bearing is based on a considerable part of Lutheran theology, this seems to be attested not only by the inscription and the associated impossibility of purchased forgiveness of sins , but also by the radical reduction to what is happening. No angels , saints and demons as in the Isenheim Altar, no allegories and no encrypted Latin messages cover the message of the picture. In the crucifixion, which is also reduced to theological statement, one even likes the juxtaposition of the introverted, emotional Mary and the advancing, preaching John as a symbolization of an emotional, Catholic experience of faith on the one hand and a theology of the Reformation reduced to scripture and intellectualized on the other detect.

Material and state of restoration

The first considerations about restoring the panel date back to 1857; however, the project was not implemented. At least the back must have been in a clearly recognizable condition because it was particularly highlighted. When the picture was removed from the church in 1875, the condition had deteriorated beyond recognition, the panel (including the front) was felt to be “no longer usable” and “unfortunately so damaged by moisture, age and worm bites that hardly any of them were left colored areas were recognizable. ” After the purchase by Edward Habich, the panel was restored in the workshops of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich in 1883 by the restorer Alois Hauser jun. split, the now separated image carriers thinned out and stabilized with a glued wooden grid (so-called parquet ). The overpainting and additions then made are not documented. After they were returned to the Tauberbischofsheimer parish, the separate pictures were hung on the wall of the choir, where they rapidly deteriorated within just ten years due to the dampness of the wall; in some cases, entire areas became detached, so that the wooden picture carrier became visible. This process is also attributed to the splitting of the board, as the board, which had previously been protected by priming and painting on both sides, now reacted more sensitively to moisture.

In the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, the first restorations began possibly from 1901, cleaning has been documented for 1910. Marga Eschenbach, restorer of the Kunsthalle, stabilized the picture carrier in the course of a major restoration work in 1926, applied a primer and wood patches to the back and removed blistering of the paint layer. This condition remained stable for a very long time, in 1988 the picture was glazed and only minimal defects and cracks were repaired. A comprehensive inventory and material analysis of the pictures did not begin until 1993, which, in addition to documenting the overpainting phases, was followed by a comprehensive restoration.

The split wooden panels of the altar consist of 13 individual fir wood boards with a variable width from 6.5 to 13.5 cm. These are glued together without a stabilizing insert of fabric. The outer boards are noticeably narrow, so that this could be an indication of a later lateral trimming of the wooden panel before the restoration in 1883. The original thickness of the board can no longer be determined, as the halves were thinned out after the split and placed on a wooden lattice on the back for stabilization. The current thickness of the picture carrier is 2 mm and thus prevents cracking due to differences in moisture and warping of the wood. A possible dowelling of the wooden boards and the later added tenons for rotating the board mentioned in the sources of the 18th century may have been lost during the thinning.

reception

In contrast to his contemporaries such as Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Dürer , Grünewald's work did not gain a comparable broad impact until the 19th century. This may primarily be due to the lack of graphic works with comparably high editions or the passing on in a Grünewald-specific painting school. The necessity of rediscovering Grünewald and identifying his real name only in the 20th century is evidence of this fact. The Tauberbischofsheimer Altar only became known to the public with its identification by Oskar Eisenmann in 1873 and the subsequent presentation in Kassel and Karlsruhe.

The first and best-known literary description of the Tauberbischofsheimer Kreuzigung comes from the French-Dutch writer Joris-Karl Huysmans , who viewed the work in the Kassel Gemäldegalerie in 1888. In his novel Là-bas , published in 1891, Huysmans involved his main character Durtal and his friend in a conversation about the alleged evil of naturalism . The "primitive" painters of the 15th and 16th centuries, who have been praised as exemplary, move into the center of the conversation. Grünewald's work is interpreted and linguistically exaggerated with haunting language. This passage of the novel appeared in an abridged and - due to the expressive brutality of the original - linguistically softened translation in 1895 in the German art magazine Pan . The publication of this picture description made a decisive contribution to the reception of Grünewald's entire work. Until then, Grünewald research was an art-historical specialty and at most the Isenheim Altarpiece was partially known to the public, but now the generation of artists of this time increasingly discovered Grünewald's visual language. One of the first artists to be inspired by this was Arnold Böcklin . He was followed by Max Beckmann , Oskar Kokoschka , Paul Klee , August Macke and Pablo Picasso , among others .

The Grünewald reception in the 20th century was mainly shaped by the much more monumental Isenheim Altarpiece. The Tauberbischofsheimer altar as Grünewald's swan song and picturesque late work mostly remained in the shadow of interest. In the textual translation of Huysman's description of the Tauberbischofsheimer crucifixion it says in summary:

“Grünewald was the most obsessed among the idealists. Never had a painter so magnificently steepled himself up and with such determination jumped from the top of the soul into the swinging circle of a sky. He had gone to extremes and, triumphant in the feces, he had distilled the finest mints of love, the hottest essences of tears. On this canvas the masterpiece of oppressed art was revealed, which is commanded to reproduce the invisible and the tangible, to reveal the tear-blurred uncleanliness of the body, to increase the infinite distress of the soul to the sublime. No, this did not find anything equivalent in any language (...) "

literature

- Heinrich Feurstein : Matthias Grünewald . Bonn 1930.

- Walther Karl Zülch : The historical Grünewald . Bruckmann, Munich 1938.

- Kurt Martin : Grünewald's crucifixion of the Karlsruhe gallery in the description by Joris-Karl Huysmans . Publisher Florian Kupferberg, Mainz 1947.

- Jan Lauts (Hrsg.): Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe - Catalog of Old Masters up to 1800 . Karlsruhe 1966.

- Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (ed.), Christian Müller: Grünewald's works in Karlsruhe . Karlsruhe 1984.

- Howard C. Collinson: Three Paintings by Mathis Gothart-Neithart called "Grünewald". The Transcendent Narrative as Devotional Image . (unprinted dissertation Yale University 1986)

- Ewald Maria Vetter : The sold Grünewald. Tauberbischofsheimer trilogy . In: Yearbook of the State Art Collections in Baden-Württemberg , Volume 24, 1987, pp. 69–117

- Karen van den Berg: The passion to paint. For image perception with Matthias Grünewald . (Dissertation Basel 1995), Duisburg Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-932256-00-X

- Karl Arndt , Bernd Moeller : Mathis Gothart's books and last pictures of the so-called Grünewald . News of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class, No. 5 (2002), ISSN 0065-5287

- Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (ed.), Jessica Mack-Andrick u. a. (Red.): Grünewald and his time . (on the occasion of the Great State Exhibition in Baden-Württemberg). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-925212-71-0

- Dietmar Lüdke: The "crucifixion" of the Tauberbischofsheimer altar in the context of the pictorial tradition . In: Grünewald and his time . 2007, pp. 209-240

- Jessica Mack-Andrick (I): The “Carrying of the Cross” of the Tauberbischofsheimer Altar as an example of devotional image strategies . In: Grünewald und seine Zeit , 2007, pp. 241–272

- Jessica Mack-Andrick (II): Viewed from both sides - reflections on the Tauberbischofsheimer altar . In: Grünewald and his time . 2007, pp. 68-77

Individual evidence

- ↑ Collinson (1986), p. 160.

- ↑ Arpad Weixlgärtner: grünewald , Vienna Munich 1962, p. 106 and Lauts (1966) p. 131.

- ↑ van den Berg (1997) pp. 215f.

- ↑ Mainz City Archives, HBA I, 50, Volume II, Folio 12r. Quoted from: Grünewald und seine Zeit (2007) p. 68.

- ^ Hugo Ehrensberger: On the history of the benefit in Bischofsheim . In: Freiburg Diocesan Archive , Volume 23 (1893) p. 139 f.

- ↑ Zülch (1938), p. 261.

- ↑ Granting of a special temporal reduction in the penalties for sin ( indulgence ) “to all believers of both sexes who received the sacrifice of the Mass at the above-mentioned altar of St. Have celebrated or participated in the cross ” . Quoted from W. Ogiermann: Tauberbischofsheim in the Middle Ages . In: From the history of an old official town , Tauberbischofsheim 1955, p. 280.

- ^ Ewald Maria Vetter: Matthias Grünewalds Tauberbischofsheimer Kreuztragung. Reconstruction and interpretation , in: Pantheon Volume 43 (1985), p. 42.

- ↑ W. Ogiermann: Tauberbischofsheim in the Middle Ages . In: From the history of an old official town , Tauberbischofsheim 1955, p. 282.

- ↑ Jessica Mack-Andrick (II) 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Collinson (1986), p. 190.

- ↑ Karin Achenbach-Stolz: Matthias Grünewald's "Carrying of the Cross" from a restoration perspective . In: Grünewald and his time, 2007, p. 112.

- ↑ For details on the change of ownership of the altar from 1875 to 1900: Ewald Maria Vetter: The sold Grünewald. Tauberbischofsheimer trilogy . In: Yearbook of the State Art Collections in Baden-Württemberg , Volume 24 (1987) pp. 69–117.

- ^ Oskar Eisenmann: The Habich Collection . In: Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst , New Series, Volume 3 (1892) p. 136. It is likely that only the crucifixion was accessible to the public, as the carrying of the cross was too damaged.

- ↑ On the function of ugliness in the medieval tradition, see: Umberto Eco: The history of ugliness , Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-446-20939-8 , p. 72ff.

- ↑ Christian Müller (1984) p. 17f.

- ↑ Zülch (1938) p. 369.

- ↑ Detailed information on the text version in: Karl Arndt and Bernd Möller (2002) p. 265.

- ↑ Joseph Braun: The Christian Altar in its Development , Munich 1924, Volume 2, p. 503.

- ↑ quoted from: Arndt and Möller (2002), p. 258.

- ↑ cf. Berndt Hamm: The Reformation as a media event , In: Yearbook for Biblical Theology , Volume 11 (1996), pp. 137–166.

- ↑ in detail on the Reformation interpretation: Karl Arndt and Bernd Möller (2002).

- ↑ On the history of the restoration see: Ewald Maria Vetter: The sold Grünewald. Tauberbischofsheimer trilogy . In: Yearbook of the State Art Collections in Baden-Württemberg , Volume 24 (1987) pp. 79f.

- ↑ Vetter (1987) p. 73.

- ↑ The restoration phases in the Kunsthalle are documented by Karin Achenbach-Stolz, in: Grünewald und seine Zeit , 2007, pp. 105f.

- ↑ The current research results on the material are taken from: Karin Achenbach-Stolz: Matthias Grünewald's "Carrying of the Cross" from a restoration perspective . In: Grünewald und seine Zeit , 2007, pp. 104–115.

- ^ First German edition: Joris K. Huysmans: Tief unten . Translated by Victor Henning Pfannkuche, Potsdam (Kiepenheuer) 1924.

- ↑ Ingrid Schulze: The shock of modernity. Grünewald in the 20th century , Leipzig 1991 and Brigitte Schad and Thomas Ratzka (eds.): Grünewald in the modern age: Matthias Grünewald's reception in the 20th century (Aschaffenburg Gallery), Cologne 2003.

- ↑ Quoted from: Kurt Martin (1947), p. 12.

Web links

- Grünewalds Kreuztragung - The restoration of a major work of German art. Exhibition in the State Art Gallery Karlsruhe, April 3 - September 21, 2014