Wilhelm of Prussia (1906–1940)

Wilhelm Friedrich Franz Joseph Christian Olaf Prince of Prussia (born July 4, 1906 in Potsdam , † May 26, 1940 in Nivelles ) from the House of Hohenzollern was the eldest son of the German and Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm and Crown Princess Cecilie . The opportunities for Wilhelm to acquire historical significance, which appeared several times because of his origins, did not come into play.

Life

In the monarchy

Wilhelm was the first child of the Crown Prince couple and was born in the Marble Palace . On his tenth birthday, his grandfather, Kaiser Wilhelm II , hired him as a lieutenant in the 1st Guards Regiment on foot and awarded him the Order of the Black Eagle . After the father took over command of the 1st Leib-Hussar Regiment in Danzig , the family lived in Sopot from 1912 until the Crown Prince was transferred to Berlin in January 1914. His father was absent during the First World War , after which he was in exile in the Netherlands until 1923, after which he usually lived separately from his wife. From 1914 onwards, Cecilie brought up Wilhelm and his five siblings almost alone. From 1916 Wilhelm's private tutor was Carl Kappus . The family moved into the newly built Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam in 1917 .

When the revolution became inevitable at the beginning of November 1918 , Chancellor Max von Baden tried to save the Hohenzollern monarchy by suggesting that the emperor, who had fled to Spa , abdicate, exclude the crown prince from the line of succession, transfer the crown to his grandson Wilhelm and give him the title To cede the reign to the imperial administrator and guardian of the minor emperor . The project, with which the MSPD leader Friedrich Ebert also agreed, failed due to the strict refusal of Wilhelm II.

In the republic

Even after the end of the monarchy, Wilhelm remained the candidate for successor in the Hohenzollern dynasty as head of the house and, if the monarchy was restored, as German Emperor and King of Prussia . Active monarchist forces such as the German National People's Party (DNVP) did not see the abdicated emperor or his son, who had also run away, as suitable representatives of the renewed German empire they wanted. They wanted Wilhelm as crown pretender under the name Wilhelm III. The DNVP refrained from making a corresponding proclamation only for “motives of rhythm and good taste” . In general, the emperor and crown prince met with rejection in the younger but also in the traditionalist right-wing camp because they "left the front leaderless in the hour of danger". Ecclesiastical-conservative circles doubted that the rulers of the republic should be regarded as “authorities” in the sense of Romans 13 . A spokesman, the theologian Reinhard Mumm , confessed in the Reichsbote : "My emperor is called Wilhelm III."

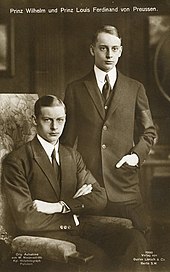

Wilhelm attended the municipal high school in Potsdam with his brother Louis Ferdinand , where he acted as a student representative for team sports such as football and handball that had previously been rejected at Prussian schools and was more popular than his intellectual and elitist brother. At the beginning of the 1920s, to the displeasure of Wilhelm II, he joined the Jungstahlhelm as a simple member . From 1925 Wilhelm studied law at the Albertus University in Königsberg , the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich and the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University in Bonn . He became a member of the Corps Borussia Bonn (1926) and corps loop bearer of the Saxo-Borussia (1928). He fought several lengths and was a second . Wilhelm did not emerge politically, but was active within the respective university groups of the Jungstahlhelm, which from 1927 joined together in the Stahlhelm-Studentenring Langemarck . In the Stahlhelmbund East Prussia , he made it to the state warden.

In 1926, Wilhelm unintentionally sparked a political scandal. The chief of the Army Command, Colonel General Hans von Seeckt , had allowed him to take part in a maneuver of Infantry Regiment No. 9 , which continued the tradition of "his" 1st Guard Regiment, without consulting Reichswehr Minister Otto Geßler . The left-liberal Gessler took the incident, which was particularly denounced by the left-wing press, as an opportunity to have Seeckt, who was enemies of him, deposed.

In 1927, the impostor Harry Domela caused a renewed interest in his person from Germany and Europe, which Wilhelm did not want . From November 1926, he had pretended to be him in Thuringia and fooled the pillars of society with his intelligent and cultivated manner. Domela was discovered in December, arrested in January 1927 and sentenced to seven months in prison. Well-known authors, including Thomas Mann , Kurt Tucholsky and Carl von Ossietzky , celebrated his " Köpenickiade " in the still monarchist and authoritarian milieu of German dignitaries. The Malik-Verlag published Domela's experience report with a portrait of Wilhelm on the dust jacket, until the latter had this forbidden by a court in January 1928.

Without knowing it, Wilhelm played a major role in Chancellor Heinrich Brüning's attempts to get closer to his long-term goal of restoring the monarchy. After that, Reich President Paul von Hindenburg should have exercised his office as Reich Administrator until Wilhelm had succeeded him as monarch at the age of 35. They failed because Hindenburg did not agree to a reduction in his personal power.

In the time of National Socialism

In the final phase of the Weimar Republic , the DNVP had based its policy on similarities with the National Socialists , but this only apparently bridged the sharp contrasts between the Stahlhelm and the SA . Wilhelm also welcomed first in his rare public appearances, the seizure of power of Hitler . The enthusiasm quickly evaporated when the Stahlhelm was brought into line, which ended with the takeover into the SA. In the summer of 1933, Wilhelm joined one of the circles around the deposed second Stahlhelm federal leader Theodor Duesterberg . To the Friends, which refers to two meetings of the "Langemärcker" in the summer and fall of 1933 in Naumburg had formed, Duesterberg of former adjutant included Hans-Jürgen von Blumenthal , the neoconservative editor Hans-Albrecht Herzner and later Hans-Viktor von Salviati , the Brother of Wilhelm's fiancée. A friendship developed with Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz .

In the general public, Wilhelm became known as a conqueror of rigid class boundaries because of his connection to Dorothea von Salviati (1907–1972) from Bad Godesberg . He fell in love with her as a Bonn student. The connection with a daughter of the court marshal to a sister of Kaiser Wilhelm was not considered equal according to the Hohenzollern house law and therefore met with the strict rejection of Wilhelm II and the Crown Prince. This appeared as a new chapter in the long series of generational conflicts in the Hohenzollern family.

On June 3, 1933, Wilhelm and Dorothea married without the family's knowledge. Only the best man Hubertus von Prussia was inaugurated. With that, Wilhelm had renounced his first-born right and his successor role was passed on to his next-born brother Louis Ferdinand. Hitler now told third parties that with this break in tradition by the Hohenzollerns, the “monarchical idea was buried in Germany”. Nevertheless, at times he considered Wilhelm suitable to take on a representative role in the Nazi state . Wilhelm himself had already declared in April 1933 that his father and grandfather's ideas of a return to the monarchy under the National Socialists were illusions. With the " restoration of military sovereignty ", Wilhelm wanted to start a career as an active officer in the Wehrmacht. Hitler prevented this despite the support of the highly respected Field Marshal August von Mackensen . Wilhelm became a reserve officer in the 1st Infantry Regiment in Königsberg . From 1935 on he lived as a landowner and farmer with his wife and their two daughters Felicitas and Christa at Klein Obisch Castle near Glogau in Silesia .

In 1938, Wilhelm's Circle of Friends joined the initiators of the coup plans, known as the September conspiracy. The trigger for the plans was the thought that Hitler's policy in the Sudeten crisis would steer Germany into a war against the Western powers that was hopeless from the start. The conspirators wanted to take Hitler prisoner in the Reich Chancellery with a raiding party under Erwin von Witzleben . He should either be brought to justice or declared by doctors to be insane. Several meetings between Wilhelm and Hans Oster , the main participant and employee of Wilhelm Canaris in the defense , are documented. In addition, Heinz had made contacts with representatives of the social democratic camp such as Wilhelm Leuschner , Julius Leber and Gustav Dahrendorf , with the trade unionist Hermann Maaß and bourgeois opposition members around Carl Friedrich Goerdeler , which came about with the replacement of the Nazi state by a constitutional monarchy based on the example of Great Britain agreed and strictly refused to return to “Wilhelmine conditions”.

In the first half of August 1938, the participants met in Klein Obisch and discussed a draft constitution with Wilhelm. Previously, there had been disagreement over who should take on the role of head of state in the intended military dictatorship . In the end, Goerdeler agreed to proclaim Wilhelm Reich regent and later to put him at the head of a re-established monarchy.

It is unclear whether Wilhelm was aware of the intention of the shock troop participants Oster and Heinz, which was kept secret from the other conspirators, to kill Hitler in a bogus scuffle when he was arrested. As a participant in the conspiracy that had already gotten stuck, Heinz clarified the failure of the coup attempt to Wilhelm a week after the Munich conference . In the Munich Agreement , Hitler had thanks to the appeasement policy enforced by the Western powers and was at the height of his foreign policy successes. In view of this, the conspirators refrained from continuing their enterprise.

After the outbreak of World War II in October 1939, Germany had begun an apparently impossible war by invading Poland . This time the liquidation of the entire Nazi leadership, free elections, a return to the rule of law and the initiation of peace negotiations were planned. A restoration of the monarchy was not planned. The pretender to the throne, Louis Ferdinand, would have been ready, but he was difficult to assess, and Wilhelm had made it clear that he was opposed to a coup d'état in war.

Death and burial

When Wilhelm took part in the French campaign in May 1940 as a first lieutenant with the 1st Infantry Division of the Wehrmacht , he was seriously wounded on May 23, 1940 when he stormed Valenciennes . He died three days later in a field hospital in Nivelles, Belgium. After his last will , which he had communicated to Salviati, Heinz brought the news of his death to the widow and took over the care of the daughters.

The public learned nothing of the prince's death from the press and radio. The news itself and the place and date of the funeral could only be obtained through obituary notices and word of mouth. On May 29, 1940, after the funeral service in the Friedenskirche, 50,000 people dressed in black formed a three kilometer long, silent trellis through Sanssouci Park to the Temple of Antiquities , the place of burial. The monarchical-conservative part of the opposition to the Nazi regime saw Wilhelm as a bearer of hope until the end of his life. The largest unorganized mass rally in his reign prompted Hitler to announce the Prince's Decree , which initially prohibited members of former German ruling houses from serving at the front and from 1943 onwards from serving in the Wehrmacht.

The funeral of Wilhelm had shown for the last time the considerable size of the potential counter- charisma of the former ruling family to Hitler. However, she did not use it in any way against National Socialism either during Wilhelm's lifetime or later. The Gestapo only came across the September conspiracy of 1938 and its ramifications during the investigation into the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 . In October 1944 Walter Huppenkothen put it in the picture, Hitler ordered absolute secrecy of the findings and forbade them to be passed on to the Upper Reich Prosecutor .

children

- Felicitas Cecilie Alexandrine Helene Dorothea Princess of Prussia (* June 7, 1934 in Bonn; † August 1, 2009 in Wohltorf ) ∞ I. Bonn September 12, 1958 (divorced 1972) Dinnies von der Osten (* May 21, 1929 in Köslin ) ; ∞ II. Aumühle October 27, 1972 Jörg von Nostitz-Wallwitz (born September 26, 1937 in Verden / Aller)

- Christa Friederike Alexandrine Viktoria Princess of Prussia (born October 31, 1936 in Klein Obisch) ∞ Election March 24, 1960 Peter Liebes (born January 18, 1926 in Munich, † May 5, 1967 in Bonn)

literature

- Prince Wilhelm von Preussen , in: Internationales Biographisches Archiv 09/1955 of February 21, 1955, in the Munzinger Archive ( beginning of article freely available)

Web links

- Wilhelm Prince of Prussia at preussen.de

- Wilhelm von Prussia in the photo collection of Haus Doorn

- Prussia, Wilhelm von; 1906–1940 , entry in the German Central Library for Economics

Individual evidence

- ↑ Helga Tödt: The Krupps of the East. Schichau and his heirs. An industrial dynasty on the Baltic Sea . Pro Business 2012, ISBN 978-3-86386-345-6 , p. 120.

- ↑ On the policy of the MSPD on the question of abdication at the end of October / beginning of November 1918 see Lothar Machtan : Kaisersturz. Failure at the Heart of Power 1918 . Theiss, Darmstadt 2018, ISBN 978-3-8062-3760-3 , pp. 150–156.

- ↑ For the rescue plan see Theodor Eschenburg : Max von Baden . In other words: The improvised democracy. Collected essays on the Weimar Republic . Piper, Munich 1963, pp. 103-109.

- ^ Gestalten around Hindenburg (anonymous, by Kurt von Reibnitz ). Reisser, Dresden 1928, p. 170.

- ↑ On the "widespread basic attitude" see Susanne Meinl : National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 274 f., There the quote from Hermann Ehrhardt (1926, Bund Wiking ) and similarly Theodor Duesterberg (Stahlhelm, 1933).

- ↑ Romans. Chapter 13 in the Luther edition from 1912 at Bibel-online.net

- ↑ Quotation from Karl Kupisch : The German regional churches in the 19th and 20th centuries . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1975, ISBN 3-525-52376-9 , p. 99 f.

- ↑ See Wilhelm's biography in Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , pp. 196-201.

- ↑ Kösener Corpslisten 1960, 9/1013; 66/1460

- ^ B. von Donner: Memories of the Prince Wilhelm of Prussia . Deutsche Corpszeitung 6/1958, p. 189 f.

- ^ Wolfram Pyta : Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler. Siedler, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-88680-865-6 , pp. 650–653.

- ↑ On the “Naumburger Kreis” around Wilhelm see Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 200.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 293 f .; on Hitler's quotation p. 411, footnote 68.

- ^ Opposite the journalist Bella Fromm , Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 198.

- ↑ Theo Schwarzmüller: Between Kaiser and "Führer". Field Marshal General August von Mackensen. A political biography . Schöningh, Paderborn, Munich, Vienna, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-506-78283-5 , p. 375.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 311.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 291 f.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 293.

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann . Resistance, coup, assassination. The fight of the opposition against Hitler . Ullstein, Frankfurt (M.), Berlin, Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-548-03077-7 , p. 703, footnote 253.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 300.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 308 f.

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 311.

- ↑ See on this and on the later funeral service Gerd Heinrich : Geschichte Preußens. State and dynasty. Ullstein, Frankfurt / M., Berlin, Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-548-34216-7 , p. 515 f.

- ^ Stephan Malinowski : The Hohenzollern and Hitler. Cicero online, June 30, 2005, accessed February 14, 2020 .

- ^ Susanne Meinl: National Socialists against Hitler. The national revolutionary opposition around Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz . Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-613-8 , p. 326.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Prussia, Wilhelm von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wilhelm Friedrich Franz Joseph Christian Olaf of Prussia; Prince of Hohenzollern |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German nobleman, Prince of Prussia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th July 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Potsdam |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 26, 1940 |

| Place of death | Nivelles |