Othello

| Othello, The Moor of Venice | |

|---|---|

Title page facsimile from the First Folio, (1623) | |

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Date premiered | 1 November 1604 |

| Place premiered | Whitehall Palace, London, England |

| Original language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Venice and Cyprus |

Othello, The Moor of Venice is a tragedy by William Shakespeare based on the short story "Moor of Venice" by Cinthio, believed to have been written in approximately 1603. The work revolves around four central characters: Othello, his wife Desdemona, his lieutenant Cassio, and his trusted advisor Iago. Attesting to its enduring popularity, the play appeared in 7 editions between 1622 and 1705. Because of its varied themes — racism, love, jealousy and betrayal — it remains relevant to the present day and is often performed in professional and community theatres alike. The play has also been the basis for numerous operatic, film and literary adaptations.

Source

The plot for Othello was developed from a story in Cinthio's the Hecatommithi, "Un Capitano Moro", which it follows closely. The only named character in Cinthio's story is "Disdemona", which means "unfortunate" in Greek; the other characters are identified only as "the standard-bearer", "the captain", and "the Moor". In the original, the standard-bearer lusts after Disdemona and is spurred to revenge when she rejects him. Unlike Othello, the Moor in Cinthio's story never repents the murder of his beloved, and both he and the standard-bearer escape Venice and are killed much later. Cinthio also drew a moral (which he placed in the mouth of the lady) that European women are unwise to marry the temperamental males of other nations.[1]

Othello's character, in particular, is believed to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the 17th century.[2]

Date and text

The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on October 6, 1621 by Thomas Walkley, and was first published in quarto format by him in 1622, printed by Nicholas Okes, under the title The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice. Its appearance in the First Folio (1623) quickly followed. Later quartos followed in 1630, 1655, 1681, 1695, 1699 and 1705; on stage and in print, it was a popular play.

Characters

- Othello, a Moor in the service of the Republic of Venice and Desdemona's husband

- Desdemona, Othello's wife and Brabantio's daughter

- Iago, Othello's ensign (standard bearer)

- Emilia, Iago's wife and Desdemona's maid

- Cassio, Othello's lieutenant

- Bianca, a courtesan involved with Cassio

- Brabantio, a Venetian senator and Desdemona's father

- Roderigo, a Venetian who harbours an unrequited love for Desdemona

- Duke of Venice, or the "Doge"

- Gratiano, Brabantio's brother

- Lodovico, Brabantio's kinsman and Desdemona's cousin

- Montano, Othello's Venetian predecessor in the government of Cyprus

- Clown, Montano's servant

- Officers, Gentlemen, Messenger, Musicians, Herald, Sailor, Attendants, servants etc.

Synopsis

The play opens with Roderigo, a rich and foolish gentleman, complaining to Iago, a high-ranking soldier, that Iago has not told him about the secret marriage between Desdemona, the daughter of a Senator named Brabantio, and Othello, a black general of the Venetian army. He is upset by this development because he loves Desdemona and has previously asked her father for her hand in marriage. Iago is upset with Othello for promoting a younger man named Michael Cassio above him, and tells Roderigo that he (Iago) is simply using Othello for his own advantage. Iago's argument against Cassio is that he is a scholarly tactician and has no real battle experience from which he can draw strategy. By emphasizing this point, and his dissatisfaction with serving under Othello, Iago convinces Roderigo to wake Brabantio and tell him about his daughter's marriage. After Roderigo rouses Brabantio, Iago says aside that he has heard rumors that Othello has had an affair with his wife, Emilia. This acts as the second explicit motive for Iago's actions. Later, Iago tells Othello that he overheard Roderigo telling Brabantio about the marriage and that he (Iago) was angry because the development was meant to be secret. This is the first time in the play that we see Iago blatantly lying.

News arrives in the Senate that the Turks are going to attack Cyprus; therefore Othello is summoned to advise. Brabantio arrives and accuses Othello of seducing Desdemona by witchcraft, but Othello defends himself successfully before an assembled Senate, explaining that Desdemona became enamored of him for the stories he told of his early life.

By order of the Duke, Othello leaves Venice to command the Venetian armies against invading Turks on the island of Cyprus, accompanied by his new wife, his new lieutenant Cassio, his ensign Iago, and Iago's wife Emilia, who works as a maid to Desdemona. When they arrive, they find that a storm has destroyed the Turkish fleet, and all break out in celebration.

Iago, who resents Othello for favoring Cassio, takes the opportunity of Othello's absence from home to manipulate his superiors and make Othello think that his wife has been unfaithful. He persuades Roderigo to engage Cassio in a fight, then gets Cassio drunk. When Othello discovers Cassio drunk and in a fight, he strips him of his rank and confers it upon Iago, which in turn strips Iago of one of his two stated reasons to exact revenge on Othello. After Cassio sobers, Iago persuades Cassio to have Desdemona act as an intermediary between himself and Othello, hoping that she will persuade the Moor to reinstate Cassio. It is of some note that throughout the text, Othello and other characters refer to Iago as "good" and "honest".

Iago now persuades Othello to be suspicious of Desdemona and Cassio. As it happens, Cassio is courting a woman named Bianca, who is a seamstress and prostitute. Desdemona drops a handkerchief that was Othello's first gift to her and which he has stated holds great significance to him in the context of their relationship; Emilia obtains this for Iago, who has asked her to steal it, having decided to plant it in Cassio's lodgings as evidence of Cassio and Desdemona's affair. Emilia is unaware of what Iago plans to do with the handkerchief. After he has planted the handkerchief, Iago tells Othello to stand apart and watch Cassio's reactions while Iago questions him about the handkerchief. He goads Cassio on to talk about his affair with Bianca; because Othello cannot hear what they are saying, Othello thinks that Cassio is referring to Desdemona. Bianca, on discovering the handkerchief, chastises Cassio. Enraged and hurt, Othello decides to kill his wife and orders Iago to kill Cassio.

Iago convinces Roderigo to kill Cassio because Cassio has just been appointed in Othello's place, whereas if Cassio lives to take office, Othello and Desdemona will leave Cyprus, thwarting Roderigo's plans to win Desdemona. Roderigo attacks Cassio in the street after Cassio leaves Bianca's lodgings and they fight. Both are wounded. Passers-by arrive to help; Iago joins them, pretending to help Cassio. Iago secretly stabs Roderigo to stop him talking and accuses Bianca of conspiracy to kill Cassio.

In the night, Othello confronts Desdemona, and then kills her by smothering her in bed, before Iago's wife, Emilia, arrives. At Emilia's distress, Othello tries to explain himself, justifying his actions by accusing Desdemona of adultery. Emilia calls for help. The Governor arrives, with Iago and others, and Emilia begins to explain the situation. When Othello mentions the handkerchief (distinctively embroidered) as proof, Emilia realizes what Iago has done; she exposes him, whereupon Iago kills her. Othello, realizing Desdemona's innocence, attacks Iago but does not kill him, saying that he would rather have Iago live the rest of his life in pain. Lodovico, a Venetian nobleman, apprehends both Iago and Othello, but Othello commits suicide with a dagger, holding his wife's body in his arms, before they can take him into custody. At the end, it can be assumed, Iago is taken off to be tortured and possibly executed.

Themes and tropes

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2007) |

Othello's racial classification

There is no consensus over Othello's racial classification. Othello is referred to as a "Moor", but for Elizabethan English people, this term could refer either to the Berbers or Arabs of North Africa, to the people now called "black", or to Muslims in general. In his other plays, Shakespeare had previously depicted what he called a "tawny Moor" (in The Merchant of Venice) and a black Moor (in Titus Andronicus).

E.A.J. Honigmann, the editor of the Arden edition, concludes that Othello's race is ambiguous. Various uses of the word 'black' (for example, "Haply for I am black") are insufficient evidence, Honigmann argues, since 'black' could simply mean 'swarthy' to Elizabethans.[3] Moreover, Iago twice uses the word 'Barbary' or 'Barbarian' to refer to Othello, seemingly referring to the Barbary coast inhabited by the "tawny" Moors. Roderigo calls Othello 'the thicklips', which seems to refer to European conceptions of Sub-Saharan African physiognomy, but Honigmann counters that, arguing that because these comments are all insults, they need not be taken literally.[4] Furthermore, Honigmann notes a piece of external evidence: an ambassador of the Arab King of Barbary with his retinue stayed in London in 1600 for several months and occasioned much discussion. Honigmann wonders whether Shakespeare's play, written only a year or two afterwards, might have been inspired by the ambassador.[5]

Michael Neill, editor of the Oxford Shakespeare edition, disagrees, arguing that the earliest external references to Othello's colour (Thomas Rymer's 1693 critique of the play, and the 1709 engraving in Nicholas Rowe's edition of Shakespeare) assume him to be a black man, while the earliest known North African interpretation was Edmund Kean's production of 1814.[6] Modern-day readers and theatre directors now normally lean towards the "black" interpretation, and North African Othellos are rare.[7]

Iago / Othello

Although the title suggests that the tragedy belongs primarily to Othello, Iago is also an important role and has more lines than the title character. In Othello, it is Iago who manipulates all other characters at will, controlling their movements and trapping them in an intricate net of lies. A. C. Bradley — and more recently Harold Bloom — have been major advocates of this interpretation.[8]

Other critics, most notably in the later twentieth century (after F. R. Leavis), have focused on Othello. Apart from the common question of jealousy, some argue that his honour is his undoing, while others address the hints of instability in his person (in Act IV Scene I, for example, he falls "into a trance").[citation needed]

Sexuality

At the beginning of the 21st century, several critics inferred that the relationship between the Moor and his Ancient is one of Shakespeare's characteristic subtexts of repressed homosexuality. Most notably David Somerton, Linford S. Haines and JP Doolan-York in their 2006 publication "Notes for Literature Students on the Tragedy of Othello", devote several chapters to arguing the case for 'Sexuality and Sexual Imagery' in the play. They analyze in great depth the play's climax, Act III Scene III, with its oaths, vows, and formal, semi-ritualistic declarations of love and commitment as being a dark parody of a heterosexual wedding ceremony; they continue by saying that Iago replaces Desdemona in Othello's affections.

Somerton, Haines, and Doolan-York come to the conclusion that Iago is a pre-Jungian expression of Shakespeare's shadow, his repressed homosexuality (which remains the subject of much heated debate among today's scholars). This also would explain why the antagonist of this tragedy is so much more appealing and developed as a character than in any of Shakespeare's other plays. The discourse concludes with the speculation that Shakespeare has drawn on the androphilia of Classical society and that Iago's unrequited love for the General is the explanation for his otherwise motiveless but passionate loathing.

Critical analysis

There have been many differing views on the character of Othello over the years. They span from describing Othello as a hero to describing him as an egotistical fool. A.C Bradley calls Othello the "most romantic of all of Shakespeare's heroes" and "the greatest poet of them all". On the other hand, F.R. Leavis describes Othello as "egotistical". There are those who also take a less critical approach to the character of Othello such as William Hazlitt. Hazlitt makes a statement that would now be regarded as xenophobic, saying that "the nature of the Moor is noble...but his blood is of the most inflameable kind".

Laurence Olivier in his book, On Acting offers a comical fiction of how Shakespeare came to write Othello. He imagined Richard Burbage and Shakespeare getting drunk one night together and, as drunken colleagues are wont to do, both begin bragging about their greatness until finally he imagined Burbage to shout, "I'm the best actor and there's nothing you can write that I can't perform!"

Performance history

Othello possesses an unusually detailed performance record. The first certainly-known performance occurred on November 1, 1604, at Whitehall Palace in London. Subsequent performances took place on Monday, April 30, 1610 at the Globe Theatre; on November 22, 1629; and on May 6, 1635 at the Blackfriars Theatre. Othello was also one of the twenty plays performed by the King's Men during the winter of 1612-13, in celebration of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick V, Elector Palatine.[citation needed]

At the start of the Restoration era, on October 11, 1660, Samuel Pepys saw the play at the Cockpit Theatre. Nicholas Burt played the lead, with Charles Hart as Cassio; Walter Clun won fame for his Iago. Soon after, on December 8 1660, Thomas Killigrew's new King's Company acted the play at their Vere Street theatre, with Margaret Hughes as Desdemona—probably the first time a professional actress appeared on a public stage in England.

It may be one index of the play's power that Othello was one of the very few Shakespearean plays that was never adapted and changed during the Restoration and the eighteenth century.[9] Famous nineteenth century Othellos included Edmund Kean, Edwin Forrest, Ira Aldridge, and Tommaso Salvini, and outstanding Iagos were Edwin Booth and Henry Irving.

The play has maintained its popularity into the 21st century. The most famous American production may be Margaret Webster's 1943 staging starring Paul Robeson as Othello and Jose Ferrer as Iago. This production was the first ever in the United States of America to feature a black actor playing Othello with an otherwise all-white cast (there had been all-black productions of the play before). It ran for 296 performances, almost twice as long as any other Shakespearean play ever produced on Broadway. Although it was never filmed, it was the first nearly complete performance of a Shakespeare play released on records. Robeson had first played the role in London in 1931 opposite a cast that included Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona and Ralph Richardson as Roderigo, and would return to it in 1959 at Stratford on Avon.

Another famous production was the 1982 Broadway staging with James Earl Jones as Othello and Christopher Plummer as Iago, who became the only actor to receive a Tony Award nomination for a performance in the play.

When Laurence Olivier played his legendary and wildly acclaimed performance of Othello at the Royal National Theatre in 1964, he had developed a case of stage fright that was so profound that when he was alone onstage, Frank Finlay (who was playing Iago) would have to stand offstage where Olivier could see him to settle his nerves.[10] This performance was recorded complete on LP, and filmed by popular demand in 1965 (according to a biography of Olivier, tickets for the stage production were notoriously hard to get). The film version still holds the record for the most Oscar nominations for acting ever given to a Shakespeare film - Olivier, Finlay, Maggie Smith (as Desdemona) and Joyce Redman (as Emilia, Iago's wife) were all nominated for Academy Awards. Olivier was among the last white actors to be greatly acclaimed as Othello, although the role continued to be played by such performers as Paul Scofield at the Royal National Theatre in 1980, Anthony Hopkins in the BBC Shakespeare television production on videotape. (1981), and Michael Gambon in London stage production directed by Alan Ayckbourn in 1990.

When Patrick Stewart played Othello at the Shakespeare Theater Company in Washington, D.C., he portrayed the Moor as a white man with the other characters played by black actors.

Actors have alternated the roles of Iago and Othello in productions to stir audience interest since the nineteenth century. Two of the most notable examples of this role swap were William Charles Macready and Samuel Phelps at Drury Lane (1837) and Richard Burton and John Neville at the Old Vic Theatre (1955). When Edwin Booth's tour of England in 1880 was not well attended, Henry Irving invited Booth to alternate the roles of Othello and Iago with him in London. The stunt renewed interest in Booth's tour. James O'Neill also alternated the roles of Othello and Iago with Booth, with the latter’s complimentary appreciation of O'Neill’s interpretation of the Moor being immortalized in O'Neill’s son Eugene’s play Long Day's Journey Into Night.

Othello opened at the Donmar Warehouse in London on the 4th of December, 2007, directed by Michael Grandage, with Chiwetel Ejiofor as Othello, Ewan McGregor as Iago and Kelly Reilly as Desdemona. Despite tickets selling as high as £2000 on web-based vendors, only Ejiofor was praised by critics, winning the Laurence Olivier Award for his performance; with McGregor and Reilly's performances receiving largely negative notices.

Adaptations and cultural references

Ballet

- Othello (2002) has been performed as a ballet piece by the San Francisco Ballet featuring an Asian Desdemona, portrayed by dancer Yuan Yuan Tan.[11]

- A Othello ballet by John Neumeier, created in 1985, is still (2008) in the repertiore of the Hamburg Ballet, having had its 100th performance in 2008.

Opera

Othello is the basis for three operatic versions:

- The opera Otello (1816) by Gioacchino Rossini

- The opera Otello (1887) by Giuseppe Verdi, libretto by Arrigo Boito

- The opera Bandanna (1999) by Daron Hagen[12]

Film

- See also Shakespeare on screen (Othello).

There have been several film adaptations of Othello. These include:

- Othello (1922) starring Emil Jannings. Silent.[13]

- The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice (1952) by Orson Welles[14]

- Отелло (1955), USSR, starring Sergei Bondarchuk, Irina Skobtseva, Andrei Popov. Directed by Sergei Yutkevich. [15]

- All Night Long (1961) A British Adaptation in which the character of Othello is Rex, a Jazz Bandleader. Featuring Dave Brubeck and other Modern Jazz musicians.[16]

- Othello (1965) starring Laurence Olivier, Maggie Smith, Frank Finlay, and Joyce Redman[17]

- Othello (1981), actually shot on videotape, part of the BBC's complete works of William Shakespeare on television. Starring Anthony Hopkins and Bob Hoskins.[18]

- Otello (1986) A film version of Verdi's opera, starring Plácido Domingo, directed by Franco Zeffirelli. Won the BAFTA for foreign language film.[19]

- Otello (1990) A TV film version staring Michael Grandage, Ian McKellen, Clive Swift, Willard White, Sean Baker, and Imogen Stubbs. Directed by Trevor Nunn.

- Othello (1995) starring Kenneth Branagh, Laurence Fishburne, and Irene Jacob. Directed by Oliver Parker.[20]

- Kaliyattam (1997), in Malayalam, a modern update, set in Kerala, starring Suresh Gopi as Othello, Lal as Iago, Manju Warrier as Desdemona, directed by Jayaraaj.[21]

- O (2001) a modern update, set in an American high school. Stars Mekhi Phifer, Julia Stiles, and Josh Hartnett[22]

- Othello (2001). TV film. A modern-day adaptation in modern English, in which Othello is the first black Commissioner of London's Metropolitan Police. Made for ITV by LWT. Scripted by Andrew Davies. Directed by Geoffrey Sax. Starring Eamonn Walker, Christopher Eccleston and Keeley Hawes.[23]

- Omkara (2006) (Hindi) is an Indian version of the play, set in the state of Uttar Pradesh. The film stars Ajay Devgan as Omkara (Othello), Saif Ali Khan as Langda Thyagi (Iago), Kareena Kapoor as Dolly (Desdemona), Vivek Oberoi as Kesu (Cassio), Bipasha Basu as Billo (Bianca) and Konkona Sen Sharma as Indu (Emilia). The film is directed by Vishal Bharadwaj who earlier adapted Shakespeare's Macbeth as Maqbool. All characters in the film share the same letter or sound in their first name as in the original Shakespeare classic. It is one of the few mainstream Indian movies to contain uncensored swear-words.

- Eloise (2002) a modern update, set in Sydney, NSW, Australia.

- Jarum Halus (2008) a modern Malaysian film, in English and Malay by Mark Tan.[24]

- Othello (2008 TV movie) directed by Zaib Shaikh and starring Carlo Rota (both of Little Mosque on the Prairie fame) in the title role. This version uses an alternate definition of "Moor" as someone of the Islamic faith, and places more emphasis on the cultural clash between Othello as a Muslim and the Christianized environments of Venice and Cyprus.

Gallery of Othello images

-

"Desdemona" by Frederic Leighton, ca. 1888

-

"Othello and Desdemona in Venice" by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856)]]

-

"Othello and Desdemona" by Alexandre-Marie Colin, 1829

-

"Desdemona's Death Song" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ca. 1878-1881

-

"The Death of Desdemona" by Eugene Delacroix

-

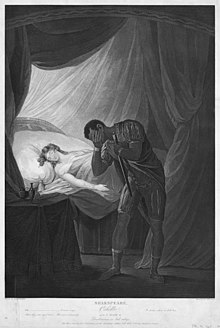

"A Bedchamber, Desdemona in Bed asleep", from Othello (Act V, scene 2), part of "A Collection of Prints, from Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakspeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain", published by John and Josiah Boydell (1803)

-

Italian actor Tommaso Salvini (1829-1915) as William Shakespeare's Othello, as depicted in Vanity Fair, May 22nd, 1875

-

American actor John Edward McCullough (1837-1885) as Othello, 1878. Colour lithograph. Library of Congress

References

- ^ Hecatommithi

- ^ Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor, Sam Wanamaker Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (cf. Mayor of London (2006), Muslims in London, pp. 14-15, Greater London Authority)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 'Black', 1c.

- ^ E.A.J. Honigmann, ed. Othello. London: Thomas Nelson, 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Honigmann, 2-3.

- ^ Michael Neill, ed. Othello (Oxford University Press), 2006, p. 45-7.

- ^ Honigmann, 17.

- ^ Shakespeare, William. Othello (Yale Shakespeare). Bloom, Harold. Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 346-47.

- ^ Laurence Olivier, Confessions of an Actor, Simon and Shuster (1982) p. 262

- ^ Great Performances . Dance in America: Lar Lubovitch's "Othello" from San Francisco Ballet | PBS

- ^ Bandanna | The opera by Daron Hagen and Paul Muldoon :: Home

- ^ Othello (1922)

- ^ The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice (1952)

- ^ See Отелло at IMDb

- ^ All Night Long (1962)

- ^ Othello (1965)

- ^ Othello (1981) (TV)

- ^ Otello (1986)

- ^ Othello (1995)

- ^ Kaliyattam (1997)

- ^ O (2001)

- ^ Othello (2001) (TV)

- ^ Jarum Halus official website

External links

- Othello — text by PublicLiterature.org

- Othello — Scene-indexed and searchable version of the text.

- Othello at IBDB lists numerous productions.

- photographs of a production of Othello