Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig

The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig (full name Ägyptisches Museum - Georg Steindorff - of the University of Leipzig ) includes a collection of around 7,000 finds from several millennia, from the Paleolithic and the pre-dynastic cultures of Egypt to all periods of Pharaonic Egypt ( early times , Old Kingdom , Middle Kingdom , New Kingdom , Late Period ) to the Greco-Roman and early Islamic periods ( Fatimid dynasty ).

history

The beginnings under Gustav Seyffarth (1840–1855)

The history of the Leipzig Museum begins with a stroke of luck. Gustav Seyffarth (1796–1885) bought a mummy-shaped coffin in Trieste for 289 thalers in 1840 . This coffin became the basis of the later Egyptian Museum and is still one of its highlights today. Seyffarth, who was a professor of archeology at the University of Leipzig , was one of the students of Friedrich August Wilhelm Spohn (1792–1824) and was soon infected by Spohn's passion for Egypt and its language. Spohn dealt with Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) and Thomas Young (1773-1829) with the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs , but his untimely death meant that hardly anything of his research results was published. After Spohn's death, Seyffarth tried to finish his work, but failed. In 1855 Seyffarth's tenure in Leipzig ended with his early retirement . He emigrated to the United States and died there in 1885.

The independent museum under Georg Ebers (1870–1889)

The next stage in the history of the Leipzig collection began after a fifteen-year break in 1870 with the establishment of a chair in Egyptology by Georg Ebers (1837–1898). For the pupil of Karl Richard Lepsius (1810–1884), the structure of Egyptology as an academic discipline, that is, teaching, was the focus of his interest. However, he did not want to limit this to the passing on of book knowledge, but to illustrate it to his students "by showing pictorial and plastic reproductions of important monuments".

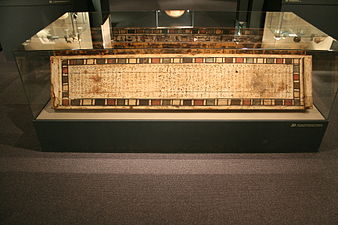

Ebers managed to buy a representative selection of plaster casts of important sculptures and a small number of originals despite small budgets. He made paper copies of reliefs and inscriptions on his own on his travels. In 1873 he discovered the famous medical papyrus of the New Kingdom, which is named after him and which he donated to the Leipzig University Library . Under Ebers, as under Seyffarth, it was usually possible for the public to visit the small collection on Sundays. In addition to his academic work, Ebers also wrote professorial novels , including "An Egyptian King's Daughter" (1864) and "Uarda" (1876). These helped to convey a vivid picture of Egypt to the general public. In 1889, like his predecessor, Ebers retired early, left Leipzig and retired in Tutzing on Lake Starnberg , where he died in 1898.

The Georg Steindorff era (1893–1934)

After another interruption, Georg Steindorff (1861–1951) was appointed to the university as successor to Ebers in 1893 . Under him the Leipzig collection received its decisive influence. Georg Steindorff was a student of Adolf Ermans (1854-1937) and had worked under his direction as assistant director at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin . Using his experience, he used a lot of strength, imagination and organizational talent to develop the small teaching display collection into a veritable museum. During his numerous trips to Egypt, he acquired objects from all periods of ancient Egyptian history in order to expand the museum's fund. He also managed to mobilize sponsors on a large scale : pre-dynastic ceramics were donated several times by the Egypt Exploration Fund in London , and after excavations in Abusir , the Berlin German Orient Society handed over the entire grave equipment of the priest Herischefhotep to Georg Steindorff. The excavations in Steindorff in 1903, 1905, 1906, 1909 and 1910 were also financed by private donations. These expanded the collection with numerous fragments of royal sculptures and magnificent stone vessels, the excavations of 1912, 1914 and 1930/31 with ceramics and other finds from the sub-Nubian Aniba and Sudanese Kerma cultures . The First World War also meant a deep turning point for those who were busy exploring Egypt on site. Many patrons had lost their personal fortune as a result of the war, and it was difficult to get money for further excavation campaigns. Steindorff was not discouraged by this, however, and through contacts with foreign colleagues he managed to make numerous new acquisitions during this time.

On May 21, 1916, the Egyptian Museum was reopened in the annex to the University's Johanneum . Over the next few years, Steindorff taught, researched and traveled and expanded the collection. With the beginning of National Socialist rule in Germany, Steindorff's field of activity was more and more restricted due to his Jewish origins. His retirement would actually have been due at the end of March 1931, but due to difficulties in finding a successor, it was initially postponed for two years and in 1932 and 1933 for a further year until it finally came into force at the end of March 1934. At the last minute he managed to emigrate with his family to the USA in March 1939, where he died in California in 1951, almost ninety years old. Steindorff deserves the great credit of having built the most important Egyptian university collection on German soil within twenty years.

National Socialism and the Post-War Period

Steindorff's student and successor, Walther Wolf (1900–1973), worked as a private lecturer at the institute and museum. In 1939 Wolff was drafted into the Wehrmacht . After the end of the war he did not return to Leipzig, probably because of his involvement in the Nazi system. During wartime he arranged for parts of the collection to be relocated.

The outsourcing was carried out by Siegfried Morenz (1914–1970). He studied theology and Egyptology at the University of Leipzig. As a research assistant “during wartime”, he packed a good 2000 objects in boxes in the spring of 1943, which were placed in two places in the Saxon province. The rest, especially the local plaster casts, significant reliefs from the Old Kingdom and Meroitic grave reliefs , remained in the museum and were destroyed during the great bombing of December 4, 1943 . Only a few remains could be recovered from the rubble.

Reconstruction of the collection from 1951

The stage of the reconstruction of Leipzig's Egyptology is also associated with the name Siegfried Morenz. First as an assistant and lecturer , later as a professor and institute director, he arranged for new accommodation on the ground floor of the university building at Schillerstraße 6. In the basement of the university building, further outsourced collections had survived the attacks. There he managed to set up a small exhibition in 1951 with some of the originals that had been seized and have since returned.

“ We don't have everything anymore, but we still have a lot, and not a little of it is good. "

(Conclusion Morenz, which he drew on the return of the objects to the Saxon Academy of Science)

After Morenz's sudden death in 1970, there was a risk that the museum's holdings would be divided among other institutes. Morenz's staff, however, campaigned for the preservation of the collection. Through various studio exhibitions in Leipzig and special exhibitions in Saxony and Thuringia , the group managed to demonstrate the indispensability of the museum within a short time and was able to realize a permanent exhibition at Schillerstrasse 6 on May 12, 1976. The reopening was not only the end of a work phase, but also marked the beginning of a new one. The aim was to consolidate and expand what had been achieved. Elke Blumenthal (* 1938) and her staff succeeded in doing this, as well as promoting and expanding the Egyptological Institute over the period of the Peaceful Revolution and the reorganization of the University of Leipzig after 1993.

The museum since 1990

Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert (* 1954) has been running the Egyptological Institute and the museum since 1999 . In November 2002, the museum had to leave its previous premises on Schillerstrasse and move to an interim location at Burgstrasse 21. The reopening took place in February 2003. In April 2010, the move to the new, permanent location in the Krochhochhaus on Augustusplatz , where the new permanent exhibition was inaugurated in June 2010.

By order of the Berlin Administrative Court on May 26, 2011, the University of Leipzig had to transfer part of the pieces offered for sale by Georg Steindorff to the University in 1936 to the Jewish Claims Conference , as the court found that Steindorff was selling the pieces below their value sold the university and a compulsion could not be ruled out due to the legal situation of Jewish citizens at the time. The University of Leipzig subsequently recognized the persecution-related withdrawal of Georg Steindorff's private collection. In an out-of-court settlement on June 22, 2011, the Jewish Claims Conference transferred all of the property back to the university in the spirit of the US-based grandson Thomas Hemer, who had advocated keeping the pieces in Leipzig. The university, in turn, undertook to make space available for the memory of Georg Steindorff in a prominent place in the museum and to point out the fate of the family of Georg Steindorff, whose sister was gassed in Bernburg in 1942, especially during guided tours for children and young people. The Steindorff Collection can thus remain in Leipzig and continue to be used for academic teaching and the interested public in the interests of its founder.

Custodians of the Collection

- Renate Krauspe (1978–1999)

- Friederike Seyfried (1999-2009)

- Dietrich Raue (since 2010)

The collection

Prehistoric and pre-dynastic times

The prehistoric part of the Leipzig collection covers a period from the Palaeolithic to the state establishment of Egypt in pre-dynastic times. The oldest pieces are hand axes and arrowheads made of chalcedony , all of unknown origin. Much of the pre-dynastic exhibits were acquired by the Egypt Exploration Fund in London and come from William Matthew Flinders Petrie's excavations in Naqada and Tarchan . A smaller part comes from the art trade , from excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir el-Meleq and from Leipzig excavations in Qau el-Kebir . The finds include club heads , make-up palettes and amulets . One focus, however, is ceramic and stone vessels , which give a broad overview of the range of shapes and decorations in pre-dynastic ceramics, especially the Naqada culture .

- Finds from prehistoric and pre-dynastic times

Early Dynastic Period

Most of the pieces from the early dynastic period come from excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir. Some pieces also come from Abydos , Tarchan and Tura or from the art trade. The focus here is on stone vessels, including a piece of Metagrauwacke with an inscription that identifies the owner of the vessel as a Sem priest of the Neith with the name Tet. Other early dynastic finds are game stones, pieces of jewelry, spoons, cylinder seals , knives and arrowheads made of chalcedony as well as a harpoon point and a hatchet made of copper .

- Finds from the early Dynastic period

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

A significant part of the Leipzig collection make findings that from 1903 to 1906 during excavations on the western cemetery of Giza Necropolis were discovered. Numerous mastaba graves from the 4th to 6th dynasties were examined. After the find was divided with the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , several grave ensembles were brought to Leipzig in whole or in part. Significant finds include numerous statues of the grave owners, such as the two standing figures of Nikauchnum and Nikauchnum and his wife, or the seated figure of Memi. From mastabah D 208 is a derived from Granite manufactured Schreiber figure of Neferihi and the grave jewelry his wife consisting of a diadem of copper with gold coating and wooden ornaments and a neck collar , a chain and two Fußbändern ceramic beads. From several graves, but above all from the mastaba of the Djascha, there are servant figures showing men and women storing and grinding grain, brewing beer and cooking.

In 1926 and 1927, the University of Leipzig once again sponsored Austrian excavations in the Westfriedhof and in return was awarded further finds, including the group of statues of the Iaiib and the Chuaut and the sarcophagus of the short civil servant Seneb .

- Finds from the West Cemetery in Giza

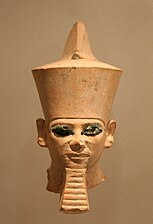

In 1910 the Leipzig excavations turned to the valley temple of the Chephren pyramid . Significant statuary finds come from here, above all numerous fragments of statues of Chephren. Among other things, four heads of smaller king statues came to Leipzig. The first (Inv. No. 1945) consists of anorthosic gneiss and is 17.2 centimeters high. The king wears a goatee and the royal headscarf , which is only partially preserved. The statue head has very individual facial features and is one of the showpieces of the Leipzig collection. A second piece (inv. No. 1946) shows Chephren in the same regalia. It is made of metagrauwacke and is 9 centimeters high. The headscarf is almost completely preserved here, as is the right shoulder. The last two pieces (inv. No. 1947 and 1948) are made of limestone and show the king with the red crown of Lower Egypt . The first measures eight centimeters and has eyes whose irises were once inlaid with flint. The eyelids originally had a copper coating . The upper body of the second piece is also partially preserved, but it is severely damaged. The king is depicted in the regalia of the anniversary festival. Here, too, the eyelids show remains of a copper coating. In addition, the Leipzig Museum is still in possession of a few smaller fragments of other Chephren statues. Other finds from the temple district are the limestone statue head of a queen and several club heads with Chephren's name.

- Finds from the valley temple of the Chephren pyramid in Giza

Other pieces from the Old Kingdom come from excavations of the German Orient Society in Abusir. These are mainly parts of wall reliefs and the upper part of a false door . The grave equipment of Herischefhotep from the First Intermediate Period also comes from Abusir . It is one of the few almost complete grave ensembles from this period and includes the inner coffin of the Herischefhotep made of painted wood, the mummy mask and mummy bandages, several bows and sticks, a headrest, sandals, a wooden statue of the deceased, a wooden, female servant figure , a kitchen courtyard model, a granary model and four boat models.

- Finds from Abusir

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period

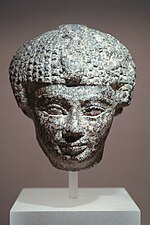

Most of the Egyptian collection items of the Middle Kingdom come from the art trade. This includes numerous statues, including royal sculptures such as the two statue heads of Sesostris I and an unknown queen made of diorite , but also private sculptures such as the standing figure of Renu or other figures of women and men made of wood, ivory and limestone. The collection also includes some ivory magic knives , memorial stones, alabaster ointment vessels and a clay house model.

- Finds from the time of the Middle Kingdom

Another focus of the collection are finds from Nubia , mainly from the excavations carried out by Steindorff in Aniba from 1912 onwards . At around the same time as the Middle Kingdom in Egypt, there was a culture that is known today as the C group . Here, too, ceramics make up a large part of the finds. Incised pattern bowls with white or colored filled geometric decor are characteristic here. Other outstanding pieces are cattle statuettes made of clay, which were probably given to the grave as symbolic food offerings, and the head of a female figure made of clay. In this piece the facial features are only hinted at. There are large holes on the sides, in which tufts of hair may originally have sat. In addition, numerous pieces of jewelry made of various materials come from Aniba.

Other Nubian finds were acquired from George Andrew Reisner , who was digging in Kerma at about the same time as Steindorff . From there several typical ceramic vessels of the Kerma culture came to Leipzig, but also other pieces of jewelery and, above all, numerous ivory carvings and mica figures in the form of animals and plants.

- Finds from Aniba

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

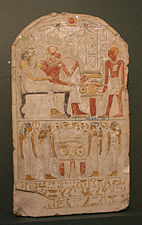

The Leipzig collection has a rich spectrum of finds from the New Kingdom, many of which come from the art trade, including numerous small finds such as ushabti , scarabs , ostraca and small sculptures (e.g. the head of a statuette of Amenhotep II ), but also several steles and relief fragments. A few pieces of the New Kingdom also come from excavations in Abusir and Qau el-Kebir.

- Finds from the time of the New Kingdom

Relief with the name of Horus Thutmose 'III.

Here, too, there is a focus on finds from Aniba. Many small finds also come from the New Kingdom cemetery there, including shabtis, scarabs, knives, tools, jewelry ( e.g. a pectoral ) and make-up utensils. There are also ceramic vessels, some with decorations, such as a bowl made of blue pebble ceramic, which depicts a lake with fish and lotus blossoms on the inside . Other objects from Aniba are bronze bowls, mummy masks and the two statues of the viceroy of Kush, Ruju. The two pieces are a seated figure and a cube stool .

- Finds from Aniba

Late Period and Ptolemaic Egypt

Most of the late and Ptolemaic finds come from the art trade. This also includes the oldest piece in the Leipzig collection, the anthropomorphic sarcophagus of Hedbastiru. It is made of cedar wood and is 212 cm high. As the coffin of Hedbastiru he stands as a cultural asset in Saxony under cultural protection .

The other pieces are relief fragments, steles, statues, amulets as well as numerous late-period small bronzes of gods and sacred animals as well as Ptolemaic terracottas of Egyptian deities in the Greek style. There are also some mummies of humans and animals.

- Finds from the late period and Ptolemaic Egypt

Terracotta figure of Harpocrates

Roman, Coptic and Arab Egypt

The Leipzig collection owns some coins and oil lamps from Roman times . The outstanding pieces from this period are a decorated vessel made of blue pebble ceramic, a very high quality statue head of a man made of basalt , the complete mummy of a young man from Hawara and mummy masks made of stucco . Several fragments of fabric, ostraca, papyrus fragments and vessels date from the Coptic period. Larger items are several tombstones and a frieze depicting the apostle Peter . The latest exhibit is a stele with Arabic inscriptions from the Fatimid period .

- Roman, Coptic and Arabic finds

Modern models and replicas

Another highlight is the pyramid model, which was commissioned in 1909 and reproduces the pyramid and mortuary temple complex of the Sahure from the 5th dynasty (2496–2483 BC) in great detail on a 1:75 scale. With a mechanism that opens the pyramid, the inside can also be seen.

War losses

Although the majority of the collection was relocated during World War II , numerous items were destroyed in the bombing on December 4, 1943. These include the plaster casts acquired by Georg Ebers, but also several originals, including the head of a figurative representation of Nefertiti from a border stele from Amarna and several large reliefs, including one from the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid in Abusir from the 5th dynasty and one from Meroe , which showed the queen Amanitenmomide (1st century AD) making a sacrifice to Osiris .

Exhibition concept

At its current location in the Krochhochhaus, the museum has ten rooms, each dedicated to their own topics. The large hall behind the entrance offers a comprehensive overview of the statues and reliefs from the Old Kingdom to the Arab period. The next mezzanine floor houses the Hedbastiru sarcophagus and is otherwise used for special exhibitions. One of the two side rooms is dedicated to the prehistory and early days of Egypt, the other to the development of the written culture. Here , clay tablets with cuneiform script from the collection of the Ancient Near Eastern Institute of the University of Leipzig are contrasted with Egyptian finds . In the rear area of the mezzanine there are two rooms in which, on the one hand, the Nubian finds from Kerma and Aniba and, on the other hand, the grave equipment of Herischefhotep are presented. In the stairwell there are two showcases, the lower one showing finds from the Ptolemaic to the Arab period and the upper one showing finds from the Amarna period . A room on the second floor is dedicated to the cult of the dead. Several mummies and grave goods from different time periods are presented here. A second room houses the model of the Sahure pyramid as well as other exhibits on the subject of the cult of the dead, including grave reliefs, mummy masks and animal mummies. The museum's foam magazine is located in the third and largest room .

Integration of the museum into teaching and cultural activities

The collection, which was set up as a teaching display collection for practical academic teaching, is still actively integrated into teaching today and offers students access to the originals. The museum's theory and practice will continue to be conveyed on the basis of the collection in the future. The Egyptian Museum therefore also offers the opportunity for internships.

The regular opening times and guided tours in the museum are supplemented by special exhibitions, monthly lectures, readings or musical evenings, which enable the general public to gain in-depth knowledge of ancient Egyptian art and culture. Since 2011, concerts, readings and discussion events have also been held in the museum hall.

literature

Museum guide

- Elke Blumenthal : Old Egypt in Leipzig: On the history of the Egyptian Museum and the Egyptological Institute at the University of Leipzig . Edited by Rector of the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1981.

- Elke Blumenthal, Volkmar Herre: Museum Aegyptiacum. Works of art from the Pharaonic period from Egypt and Nubia in the Egyptian Museum. Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1984.

- Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. In: Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997.

- Renate Krauspe : The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig. 3. Edition. Leipzig 1987.

- Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig . von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2007-8 .

- Joachim Spiegel : Short guide through the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1938.

Collection catalogs

- Renate Krauspe (Ed.): Catalog of Egyptian collections in Leipzig. Volume 1: Statues and Statuettes. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1883-9 .

- Renate Krauspe (Ed.): Catalog of Egyptian collections in Leipzig. Volume 2: Clay vessels from the pre-dynastic period to the end of the Middle Kingdom. von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-2327-1 .

- Dietrich Raue (Ed.): Catalog of Egyptian collections in Leipzig. Volume 3: Coptica. Manetho, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-447-06790-4 .

- Michael P. Streck (Ed.): The cuneiform texts of the Old Oriental Institute of the University of Leipzig (= Leipzig Old Oriental Studies. Volume 1). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-447-06578-8 .

Other fonts

- The sarcophagus of Hetnitokris recently acquired for the archaeological museum in Leipzig . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 17 . J. J. Weber, Leipzig October 21, 1843, p. 265-266 ( books.google.de ).

- Ägyptisches Museum der Universität Leipzig (ed.): The ancient Egypt (be) grasp. 40 points of contact for sighted and blind people. University of Leipzig, Leipzig 2006, ISBN 3-934178-56-1 .

- Marc Brose, Tonio Sebastian Richter: One God! Late antique Egypt in Leipzig. Special exhibition from July 28, 2008 to September 28, 2008. Leipzig 2008.

- Elke Blumenthal: A Leipzig grave monument in the Egyptian style and the beginnings of Egyptology in Germany (= small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 4). Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-934178-01-4 .

- Elke Blumenthal, Angela Onasch: Scarabs in Leipzig. The scarabs of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig (= Small Writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 7). Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-934178-45-6 .

- Elke Blumenthal u. a .: Georg Steindorff. Stations of a life (= small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 11). Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-9813741-1-7

- Heinz Felber : Caravan to the oracle of Amun. Steindorff's expedition to Amarna, Siwa and Nubia 1899/1900 (= Small Writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 5). Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-934178-09-X .

- Heinz Felber among others: shrew mummy with coffin. A new acquisition by the Egyptian Museum. Elke Blumenthal on the 60th birthday of her employees (= small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 2). Leipzig 1998.

- Heinz Felber, Susanne Pfisterer-Haas : Egyptians and Greeks. Meeting of cultures. (= Small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 1). Leipzig 1997.

- Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert , Stefan Lehmann (Ed.): Researcher - Pastor - Collector. The Egyptian Antiquities of Dr. Julius Kurth from the holdings of the Archaeological Museum of the Martin Luther University in Halle (= Small Writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 8). Leipzig 2011, ISBN 978-3-86583-584-0 .

- Sandra Müller: Georg Steindorff in the mirror of his diaries (= small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 9). Leipzig 2012, ISBN 978-3-86583-733-2 .

- Antje Spiekermann, Friederike Kampp-Seyfried: Giza. Excavations in the cemetery of the Great Pyramid by Georg Steindorff (= Small Writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 6). Leipzig 2003, ISBN 3-934178-24-3 ( PDF; 66.5 MB ).

- Frank Steinmann: Ancient Egyptian ceramics (= small writings of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. Volume 3). Leipzig 1999.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, p. 3.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 4-8.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, p. 10.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 10-13.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 10, 13.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 13-15.

- ^ Friederike Seyfried: Successful debut. In: a M un. Magazine for the friends of the Egyptian museums. Volume 17, 2003, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Kerstin Seidel, Susanne Töpfer: Finally arrived ... The Egyptian Museum - Georg Steindorff - at its new location. In: a M un. Magazine for the friends of the Egyptian museums. Volume 44, 2012, pp. 9-15.

- ^ University of Leipzig: Steindorff collection remains at University of Leipzig. June 22, 2011, accessed October 10, 2014.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 11–15.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 18-21.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 15-19.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 50-53.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 34-35.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 45-50.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 38-43.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Anna Maria Donadoni Roveri : I sarcofagi egizi dalle origini alla fine dell'Antico Regno. Roma 1969, pp. 136-137 ( PDF; 46.5 MB ).

- ^ A b c d Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974, p. 23 ( PDF 30.5 MB ).

- ^ A b Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Individual finds. A. The statue fragments from the Old Kingdom. In: Uvo Hölscher: The grave monument of King Chefren . JC Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1912, p. 92 ( PDF; 6.7 MB ).

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Individual finds. A. The statue fragments from the Old Kingdom. In: Uvo Hölscher: The grave monument of King Chefren. P. 93.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Individual finds. A. The statue fragments from the Old Kingdom. In: Uvo Hölscher: The grave monument of King Chefren. Pp. 93-94.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Individual finds. A. The statue fragments from the Old Kingdom. In: Uvo Hölscher: The grave monument of King Chefren. Pp. 94-104.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Individual finds. A. The statue fragments from the Old Kingdom. In: Uvo Hölscher: The grave monument of King Chefren. P. 102.

- ↑ Antje Spiekermann, Friederike Seyfried Kampp-: Giza. Excavations in the cemetery of the Great Pyramid by Georg Steindorff . Leipzig 2003, p. 76 ( PDF; 66.5 MB ).

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 54-56.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 57-63.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research of the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 66-70.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 71-73.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research of the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 74-75.

- ^ A b Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 40–53.

- ^ A b Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 79-102.

- ^ The Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media: Kulturgut in Sachsen ( Memento from February 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). On: kulturgutschutz-deutschland.de from 2016; last accessed on August 17, 2016.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 54–63.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 106-119.

- ^ Renate Krauspe: The Egyptian Museum of the Karl Marx University Leipzig. Guide to the exhibition . Edited by Directorate for Research at the Karl Marx University Leipzig, Leipzig 1987, pp. 61–67.

- ^ Renate Krauspe (Ed.): The Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 123-132.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: On the history of the collection. Mainz 1997, pp. 4, 6, 10.

- ^ University of Leipzig, Faculty of History, Art and Oriental Studies: Faculty of History, Art and Oriental Studies of the University of Leipzig: Tour. Retrieved September 6, 2017 .

Coordinates: 51 ° 20 ′ 23.5 ″ N , 12 ° 22 ′ 48 ″ E