Atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The US atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, 1945 were the only nuclear weapons used in a war so far .

The atomic bomb explosions killed a total of around 100,000 people instantly - almost exclusively civilians and slave laborers who had been abducted by the Japanese army . By the end of 1945, another 130,000 people had died of consequential damage. Quite a few were added over the next few years.

Six days after the second bombing was Emperor Hirohito with the speech of August 15, the termination of the " Greater East Asia Co war known". With the surrender of Japan on September 2, the Second World War also ended in Asia, after it had been over in Europe with the surrender of the German Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945.

US President Harry S. Truman , successor to Franklin D. Roosevelt , who died on April 12, 1945, gave the order to use the new weapon in the Erlenkamp house in Potsdam , where the American delegation had taken up quarters during the Potsdam Conference . Truman, formerly Roosevelt's vice president, had no knowledge of the " Manhattan Project ", the development of the atomic bomb , until he took office . The motive for using the bombs was to get Japan to surrender as quickly as possible and thus end the war. On the one hand, Truman feared that the Soviet Union would make demands on Japanese territory, on the other hand, that the planned American landing on the main Japanese islands would cause many victims among US soldiers. At that time, large areas of Asia were still occupied by Japan. Truman's decision is still discussed heavily and emotionally.

In Japan, commemoration of the victims plays an important role in national culture and self-image . World were Hiroshima and Nagasaki to symbols of the horrors of war and especially of a possible nuclear war in the days of the Cold War .

prehistory

Starting position

In the course of the Pacific War in 1944 and early 1945 , the US armed forces had moved ever closer to the main Japanese islands through the tactic of island jumping . In the Battle of the Marianas Islands in the summer of 1944 they had captured bases, the use of B-29 - long-range bombers against targets in Japan enabled. The Japanese war economy had been badly hit by a strategic air offensive . In the battles for Iwojima and Okinawa in early to mid-1945 they had worked out starting positions for a later landing on the main Japanese islands, which was prepared under the name Operation Downfall and was to take place in late 1945.

In April 1945 the USSR canceled the 1941 neutrality agreement with Japan . The Soviet Union had the United States under Truman's predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt promised at least three months after the war ended in Europe in the Pacific war against Japan to intervene, a period that ended on 8 August.

On May 28, 1945, US Ambassador Harry Hopkins, still appointed by Roosevelt, telegraphed Truman in Moscow that Soviet troops had taken a position in Manchuria for the war against Japan . Japan knows that it is lost. However, since the Japanese government would not surrender unconditionally, Stalin suggested accepting a Japanese offer for peace and then achieving one's own goals through joint occupation and administration of Japan. Stalin feared that otherwise the Tennō's regime would succeed in dividing the Allies and preparing for a war of revenge. Hopkins recommended that further action be coordinated closely with the Soviet allies in order to jointly benefit from this situation for the post-war period. However, his telegram was ignored.

Manhattan project

At the end of 1941, the Americans began preparations for a top-secret large-scale project aimed at manufacturing an atomic bomb . The occasion was reports that the German uranium project , which was also aiming for the military utilization of nuclear fission , was making progress. The project was started in 1942 under the direction of Robert Oppenheimer , and the British joined in 1943.

In the spring of 1945, the completion of the first nuclear explosive device, the later "Trinity" bomb, was approaching . Work was underway on two more bombs. An operation against German cities had at least been considered, but at the beginning of May Germany capitulated. So the US turned its gaze to Japan. The Interim Committee set up shortly after the German surrender was supposed to work out proposals for the use of the bomb. The associated Target Committee agreed on May 10 and 11, 1945 in Los Alamos to use atomic bombs against previously un-bombed Japanese cities with war industries of strategic military importance. This should bring the greatest possible psychological effect and avoid the risk of a miss when the military target selection is limited. Kyoto , Hiroshima , Yokohama , Niigata and Kokura were shortlisted as possible destinations; the Tokyo Imperial Palace , however, was rejected. On June 1, 1945, the committee recommended that the weapons be used immediately after their completion and without warning against “an armaments factory surrounded by workers' accommodation”. War Department Undersecretary Ralph Bard later raised concerns about the deployment without warning.

U.S. military invasion and dropping plans

Until the end of the war, Japan still ruled huge areas in Asia, including the Dutch East Indies and large parts of China. However, it was already considerably weakened by air strikes by the US - since February 1945 the strategic US bomber fleet had complete air sovereignty over Japan. Their intensified air strikes with incendiary bombs based on the British model had already destroyed around 60 percent of two-thirds of the major Japanese cities. In addition, Japan had by then almost completely lost its largest fleet ( Kidō Butai ), as well as the main part of the air force. The resource-poor Japan had lost its supply of raw materials.

That is why the United States Army Air Forces were convinced of the grueling effect of their air strikes and, if conventional air strikes continued unabated, expected Japan to surrender by December 1945. They believed that its regime could only hope for favorable peace conditions while maintaining state sovereignty .

However, the Battle of Okinawa in July 1945 and the Battle of Iwojima demonstrated the unbroken will of the Japanese to fight : only a fraction of their soldiers there were ready to surrender, the rest fought to the death. About 12,500 US soldiers died in the conquest of Okinawa; a total of around 70,000 US soldiers had died in the Pacific War by then. On the Japanese side, 74,000 to 107,000 soldiers were killed in the Battle of Okinawa, and around 122,000 civilians were killed - about a third of the civilian population. The United States Army expected a landing on Kyushu , especially if preparations were delayed, with strong resistance from up to ten Japanese divisions. In a landing on Honshū and Hokkaidō ( Operation Downfall ), losses of 25,000 to 268,000 US soldiers are to be expected. The USA reckoned with up to 300,000 more own deaths.

The US military did not plan to conquer the main Japanese islands until November 1945. On July 4, 1945, its leadership consulted with that of Great Britain on how to proceed in the Pacific. The British government was privy to the progress made in making atomic bombs and agreed to use them. Temporary considerations to detonate the finished bombs only as a "warning shot" over unpopulated Japanese territory were not pursued. It should be noted that after the Trinity test, the United States only had two bombs ready for use.

Mission order and ultimatum

From mid-June, the first B-29s of the 509th Composite Group arrived at North Field in Tinian . On July 9th, the Japanese ambassador Satō Naotake had already asked for peace negotiations in Moscow . The Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov was to convey this request to the participants in the upcoming Potsdam Conference of the Allies (July 17 to August 2, 1945). This conference discussed the further course of action of the victorious powers USA, Soviet Union and Great Britain in Europe and in the war against Japan.

At the beginning of the conference on July 16, Truman learned that the test bomb had been successfully detonated in the desert in the US state of New Mexico ( Trinity test ). The second bomb, Little Boy , was also shipped to Tinian Island in the Pacific, where it was to be made ready for use. Winston Churchill learned of the test success on the same day and noted in his memoirs how liberating he experienced the news in view of the prospect of costly land battles:

"Now all of a sudden this nightmare was over, and in its place there was the bright and comforting prospect that one or two crushing blows could end the war [...] Whether the atom bomb was to be used or not was not discussed at all."

General Dwight D. Eisenhower later reported that the decision to use the two atomic bombs had already been made on July 16. He had advised Truman against it because the Japanese had already signaled their willingness to surrender and the United States should not be the first to use such weapons. But Truman wrote in his diary:

"I think the Japsen will give in before Russia intervenes."

It was only on the evening of July 24th that Truman casually announced to Stalin that a new type of bomb had been developed that was capable of breaking the Japanese will to war. Truman noted in his diary that Stalin received the news unmoved and advised the United States to use the weapon for good causes. It is assumed, however, that Stalin was informed about the completion of the US atomic bombs through the employee of the Manhattan Project, Klaus Fuchs , because on the same evening he had his secret service chief Lavrenti Beria to build a Soviet atomic bomb, which had started in 1943 accelerate.

On July 25, Truman gave General Carl A. Spaatz , the Commander-in-Chief of the US Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific stationed on Tinian , the order to prepare the deployment of the first "special bomb" by August 3. He left the choice of targets to the general. On the urgent advice of his Secretary of War Stimson , however, he had Kyoto struck off the list of possible targets.

On July 26, 1945, Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration on behalf of the United States, the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek, and the United Kingdom , in which he called on the Japanese leadership to surrender immediately and unconditionally. This was not agreed with the Soviet Union. Molotov had asked the United States in vain to hold back the ultimatum for a few more days until his government terminated its non-aggression pact with Japan. But the entry of the Soviet Union into the war was now undesirable for the US government. The statement came out:

"The full use of our military might, coupled with our determination, means the inevitable and complete annihilation of the Japanese armed forces and, just as inevitably, the devastation of the Japanese homeland."

Japan will be completely occupied, democracy will be introduced, war criminals will be punished, Japan's territory will be limited to the four main islands and reparations will be demanded. Japanese industry will be preserved and will later be allowed to participate in world trade again. The alternative for Japan is immediate and total destruction.

There was no concrete indication of the planned use of a new type of weapon and its aim. Leaflets dropped in over 35 Japanese cities, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in the previous months warned their populations of upcoming air strikes and urged civilians to vacate the cities. However, they contained no reference to atomic bombs and their effects. One reason for not giving a specific advance warning was the assumption that the Japanese would move prisoners of war to the cities they warned about as human shields .

With the US invasion of the main Japanese islands not due to begin until three months later, the Japanese leadership assumed the ultimatum was the usual threat ritual to demoralize the Japanese. At the same time, she still hoped that Stalin would persuade the Western Allies to accept the initiated peace initiative. In particular, the required territorial losses seemed unacceptable. General Suzuki Kantarō's answer was :

"The government finds nothing of significant value in the joint declaration and therefore sees no other option but to ignore it completely and work resolutely to end the war successfully."

Drop on Hiroshima (Operation Silverplate)

Choice of destination

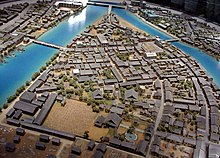

Until then, Hiroshima was one of the few major Japanese cities that had been spared bombing. It was the seat of the headquarters of the 2nd Main Army under Field Marshal Hata Shunroku , which was responsible for the defense of southern Japan. The 59th Army and the 5th Division had their headquarters here. Therefore, it was a troop assembly point and was used to store goods that were important to the war effort. 40,000 military personnel were stationed in Hiroshima. But most of the approximately 255,000 residents were civilians, ten percent of whom were Korean and Chinese slave laborers .

Spaatz found Hiroshima the most appropriate destination as it was the only one of the cities that were available to have no POW camps . Only a few US prisoners of war and around a dozen Germans were there. Hiroshima consisted of wooden structures except for a few concrete structures in the center. The US military therefore expected a firestorm . Industrial facilities in the outskirts of the city should also be destroyed.

Start preparation

In the B-29 Superfortress bombers of the “ Silverplate ” program, among other things, all on-board weapons except for the rear cannon had been removed and the bomb bays had been rebuilt in order to be able to carry a single bomb weighing several tons. Since 1943, approaches and drops have been drilled a hundred times with dummies ("pumpkin bombs"). In July 1945, 37 conventional single bombs in the size of atomic bombs were also dropped on Japanese factories. They had already practiced the turning maneuver again and again after it was triggered, in order to then avoid the pressure wave of the detonated atomic bomb as far as possible, with twelve kilometers being the minimum distance.

On July 31, the three-meter-long and four-tonne uranium bomb “Little Boy” (explosive force 12,500 tons of TNT ) was ready for use. The parts for the second bomb " Fat Man " arrived on Tinian. The start planned for August 1st had to be postponed due to a typhoon over the island. On August 4th, pilot Paul Tibbets found out what his assignment was under strictest confidentiality. He christened his aircraft, the B-29 Superfortress No. 82, in the name of his mother " Enola Gay ".

A clear cloudless sky was forecast for the Japanese islands on August 6th. At 2:45 a.m., the bomber plane took off with a crew of twelve on board. Two more B-29 aircraft, " The Great Artiste " and an aircraft that was unnamed at the time and later named " Necessary Evil ", accompanied the "Enola Gay". The military feared that the bomb could explode prematurely. William L. Laurence described what went on before the start:

"When the general was told that there was a risk that the whole island would blow up in the event of a false start, he replied, 'We must pray that this does not happen.' The same general then recounts the risky start of the machine: 'We almost tried to lift it into the air with our prayers and hopes.' Before departure, a Lutheran chaplain said a 'moving prayer':

'Almighty Father, to whom you answer the prayers of those who love you, we ask you to assist those who venture into the heights of your heaven and fight to our enemies perform. [...] We ask you that the end of this war will come soon and that we will once again have peace on earth. May the men who take the flight that night be safe in your hat and may they return to us unharmed. We will continue on our way trusting in you; for we know that we are under your protection now and for all eternity. Amen.'"

In order to reduce the risk of an accident during take-off, Captain William S. Parsons, head of the Ordnance Division of the Manhattan Project, decided to carry out the final steps in the assembly of Little Boy during the flight on the way to Hiroshima. Around three o'clock in the morning, Parsons and his colleague Morris Jepson crawled into the bomb bay of the flying Enola Gay and mounted the four sacks of cordite in the gun barrel and connected the ignition cables. About four and a half hours later, Jepson replaced the four ignition system safety plugs with sharp ignition plugs. The bomb was now fully operational and was drawing energy from its own batteries. This was done without the knowledge of Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project.

Release

After the start of Tinian, the Enola Gay flew towards Iwo Jima and from there set course for Japan. Over an hour before the launch, at 7 a.m. local time ( Japan Standard Time ), the Japanese early warning radar system detected the radar echoes of some US aircraft. Radio broadcasts were cut in several cities, including Hiroshima. At just before 8 a.m., the Hiroshima radar crew realized that the number of aircraft approaching was likely to be no more than three and the alarm was lifted. In order to save energy, fuel and aircraft, the Japanese Air Force decided not to intercept such small formations anymore. A normal radio warning advised the population to go to shelters if B-29s were actually sighted. However, this small formation was assumed to be reconnaissance aircraft, as Japan was generally overflown by reconnaissance aircraft on a daily basis. A B-29 had already flown over Hiroshima at 7:31 a.m. to check the weather conditions for the drop. At 8:15 a.m. and 17 seconds local time, the crew of the US bomber Enola Gay unplugged the bomb at a height of almost ten kilometers, whereupon the bow of the suddenly relieved machine rose. The bomber then flew a sharp 155 ° curve in order to be able to move as far away as possible from the predicted explosion site.

At 8:16 a.m. and two seconds , the atomic bomb exploded about 600 meters above the city center at 34 ° 23 ′ 41.4 ″ N , 132 ° 27 ′ 17.3 ″ E , 250 meters from the targeted target, the striking Aioi -Bridge . Within a second, the detonation wave had completely destroyed 80 percent of the city center and its thermal radiation ignited fires up to ten kilometers away. Tibbets, sitting with his back to the explosion as the commander of Enola Gay, later reported that he saw the sky light up in front of him and felt the taste of lead in his mouth. 40 seconds later, and then already about 14.5 km away, the pressure wave caught up with them and shook them vigorously.

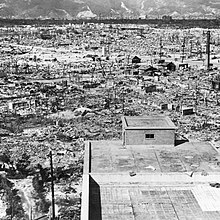

A firestorm destroyed eleven square kilometers of the city and drove the mushroom cloud characteristic of atomic bomb explosions up to a height of 13 kilometers. This spread highly contaminated material containing about 20 minutes later than Fallout (Fallout) came down to the environment. A total of 70,000 of the 76,000 houses were destroyed or damaged.

Victim

70,000 to 80,000 people died instantly. In people who stayed in the inner city center, the uppermost layers of skin literally evaporated. The blazing flash of the explosion burned silhouettes of people into the walls of a house that had not been standing before the people were carried away by the pressure wave. In the weeks that followed, the nuclear radiation, which was largely released immediately after the explosion, killed numerous other residents who, although not victims of the immediate pressure and heat wave, had received lethal doses of radiation. Many who had fled to the river from the unbearable heat and drank from the contaminated water subsequently lost their hair, developed purple spots all over their bodies, and then bled to death from internal injuries. A total of 90,000 to 166,000 people died in the drop, including the long-term consequences, according to different estimates up to 1946.

The bomb killed 90 percent of people within 500 meters of Ground Zero and still 59 percent within 0.5 to one kilometer. The residents of Hiroshima at that time are still dying of cancer as a long-term consequence of radiation. One study found that nine percent of cancers that occurred in survivors from 1950 to 1990 were a result of shedding. The survivors of the atomic bombs are known as Hibakusha in Japan .

One of the victims named by Tokyo is the Korean Prince RiGu , who was a member of the government in Korea and held an officer rank in the Japanese army. Sitting on his white horse near the Aioi Bridge, he and the horse are said to have completely evaporated from the heat.

Between the drops

No survivor from Hiroshima itself reported the incident to Tokyo. All connections were broken. It was only hours later that military bases in Hiroshima's vicinity reported a huge explosion with an unknown cause. It was initially believed that a large garrison ammunition depot had exploded. Officers who were supposed to investigate the situation on the ground were prevented from doing so by air strikes on Tokyo.

On Tuesday, August 7th, at 12:15 am, Truman reported on his way home to the United States aboard the cruiser USS Augusta to the world of the use of the atomic bomb: “The power from which the sun draws its power is on those who brought war to the Far East have been let loose . ”He called on the Japanese to surrender again and threatened:“ If they do not accept our terms, then they may expect a rain of destruction from the air, such as has never been seen on earth has been seen. "

But in Tokyo it took the war cabinet days to be clear about the extent of the destruction in Hiroshima. Even then it could not agree on an immediate unconditional surrender, since a peace initiative from Stalin on better terms for Japan was still expected. But on August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, after the neutrality pact with Japan had been terminated on April 5, 1945 . The Red Army attacked the Soviet invasion of Manchuria the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo ( Manchuria ) with over one million soldiers and also began an attack on the Kuril Islands . In doing so, the Soviet Union fulfilled its commitment to the Yalta Conference at the urging of US President Roosevelt to start the war in Europe in the Far East three months after the end of the war and to attack Japan and its allies. The declaration of war that the Japanese ambassador in Moscow was supposed to report to Tokyo never made it there.

The US government, which had expected the Japanese to surrender quickly, also dropped millions of copies of a freshly printed leaflet on August 8 over 47 Japanese cities. It compared the effect of the atomic bomb with that of 2,000 conventional bombs from a B-29: Anyone who doubts this should inquire about the fate of Hiroshima with the Japanese government. The Japanese people were called to call for an end to the war. Otherwise, more atomic bombs and other superior weapons will be used resolutely. There was no specific advance warning for the second drop.

On August 9, at 11 a.m., two minutes before the Nagasaki bomb was detonated, the Japanese War Cabinet met in Tokyo. Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo urged an immediate peace agreement; However, the military set four conditions that the Secretary of State deemed "unacceptable" to the United States:

- Preservation of Tennō empire ( granted when the Japanese surrender was later signed on September 2)

- no foreign occupation of Japan

- voluntary disarmament of the Japanese troops

- War criminals only tried in Japanese courts

The heated internal debate about it ended without result.

Drop on Nagasaki (Operation Centerboard)

Choice of destination

Nagasaki was not originally on the list of destinations, but was added to replace the old imperial city of Kyoto . By order of US Secretary of War Henry Stimson , who had once visited Kyoto and was aware of its importance as the cultural center of Japan, the city had been removed from the list of potential targets.

Nagasaki had around 240,000 to 260,000 inhabitants at the time and was an important location for the Mitsubishi armaments company, which operated large shipyards there, in which around 20,000 Korean forced laborers built and repaired cruisers and torpedo boats for the Imperial Japanese Navy , among other things . The torpedoes used by Japan to attack the US fleet on Pearl Harbor were also built there. The city was one of the possible targets of the US Air Force. Few Japanese soldiers were stationed in Nagasaki.

Start preparations

The components for the nuclear weapons gradually arrived at Tinian. Those involved were under the impression of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis on July 30, 1945. This heavy cruiser was hit by two torpedoes of the Japanese submarine I-58 after the delivery of eight bombs for the Hiroshima bomb on its way to Guam and dropped in minutes. It was the last loss of a US warship in the Pacific War. Of the almost 1,200 crew, only 318 could be rescued. Three Fat-Man-type bombs and the nuclear material for the bomb were therefore brought by the 509th Composite Group from Utah to Tinian by air. The plutonium bomb "Fat Man" with an explosive force of 22,000 tons of TNT was assembled in a great hurry and without important control tests.

The generals on Tinian decided to drop the second bomb on August 8th themselves. The basis of the order was the US President's order of July 24th, according to which the "special bombs" should be ready for use after August 3rd and should be dropped one after the other. They did not obtain another order. They moved the release date set for August 11 two days earlier, as bad weather was forecast. After assembly, before loading onto the aircraft, the exterior of the bomb, including the tail unit, was labeled with their names and slogans by a large number of employees. At around 2 a.m. on August 9, 1945, the 25-year-old pilot Charles W. Sweeney took off the Bockscar bomber with partly new crew and two escort aircraft. His destination was Kokura , a city with much more arms industry than Nagasaki.

On arrival, Kokura was under thick cloud cover; on three approaches the view was severely obstructed, so that Sweeney broke off the attack. He was only allowed to drop the bomb by sight, as he was supposed to hit the armaments factories. Since this was not possible and the jet fuel was running low, he flew to the alternative destination Nagasaki.

Release

Originally a direct attack on the shipyards was planned. Since the visibility in Nagasaki was also poor, it was not possible to carry out an exact target drop. The pilot should have stopped the attack under such circumstances, but decided to use a radar approach. Only without the bomb on board was it possible to reach Okinawa for an emergency landing. The fuel reserve in the tanks was just seven gallons (26.50 liters).

The bomb was dropped at 11:02 am local time about three kilometers northwest of the planned target point at 32 ° 46 ′ 25.6 ″ N , 129 ° 51 ′ 48.1 ″ E over densely populated areas. It was supposed to hit the Mitsubishi group, but missed its target by more than two kilometers. It destroyed almost half of the city area. The explosion about 470 meters above the ground destroyed 80 percent of all buildings - mostly wooden houses - within a radius of one kilometer and left only a few survivors behind. It exploded in a valley, so the surrounding mountains dampened the impact on the city's surroundings. The bomb set objects on fire over a distance of four kilometers. There was no firestorm. The mushroom cloud rose 18 kilometers into the atmosphere.

Victim

About 30 percent of the population lived 2,000 meters or less from ground zero . Around 22,000 people died immediately in the inner city area; another 39,000 died within the next four months. Others estimate 70,000 to 80,000 dead. The number of people injured in Nagasaki was 74,909.

Effects

End of war

The news of Nagasaki's destruction caused consternation among the Japanese government. It was feared that the United States would drop a third bomb on Tokyo. A shot down B-29 pilot fueled these rumors. On August 12th, further atomic bomb parts actually arrived at Tinian, which should be made usable by August 17th.

After twelve hours of fruitless deliberation by the war cabinet, during which the positions of the foreign minister and the military were irreconcilable, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantarō , who had not yet intervened in the debate , asked the Tennō on August 10, 1945 for his decision. Hirohito spoke for the first time and decided at 2 a.m. that the Potsdam Declaration should be accepted. With the addition that one understands this so that the Tennō could keep his sovereign rights, this decision was communicated to the Allies.

The United States then declared that the authority of the Tenno would be placed under the Allied occupation command as soon as the surrender was declared. So the Japanese declaration was not counted as such. This became known in Japan on August 12th. The Japanese generals then called on their soldiers to be prepared to commit suicide millions of times in order to “drive the invaders into the sea”.

On August 14th, Hirohito decided to surrender again to save the nation and to spare the Japanese further suffering. He himself will ask his subjects for understanding. To prevent his speech from being broadcast on the radio, younger officers, such as Hatanaka Kenji , attempted a coup . After the commander of Tokyo, General Tanaka , appeased them with a long speech, he and the leaders of the revolt committed seppuku , the traditional suicide.

The last air raid by the United States took place on August 15, 1945; it applied to the cities of Kumagaya ( Saitama Prefecture ) and Isesaki ( Gunma Prefecture ). At 4 p.m. Hirohito's speech was broadcast ( Gyokuon-hōsō ) . The Japanese gathered in the squares, who had never heard his voice before, learned how things were going in Japan:

“The enemy recently used an inhuman weapon and inflicted severe wounds on our innocent people. The devastation has reached unpredictable dimensions. To continue the war under these circumstances would not only lead to the utter annihilation of our nation, but to the destruction of human civilization ... That is why we have ordered the adoption of the joint declaration of the powers. "

The speech was followed by numerous suicides. The next day, the imperial order was issued to all troops to cease fighting. On August 30, the Allied Pacific Fleet arrived in Tokyo Bay .

On September 2, the new Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru and Chief of Staff Umezu Yoshijirō for Japan, General Douglas MacArthur for the Allies on the battleship USS Missouri signed the document of surrender. MacArthur delivered an unexpected speech calling on the victor and the vanquished to work together to build a world committed to human dignity .

On September 9, 1945, the Japanese China Army with around one million men in Nanjing finally surrendered to the national Chinese under Chiang Kai-shek. The Japanese armed forces in Southeast Asia only surrendered to the Allied forces under Lord Louis Mountbatten on September 12, 1945 in Singapore . This ended the Second World War.

Emergency aid for victims and damage analysis

For Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the end of the war meant that foreign aid, for example through the Red Cross , could now come . In the following months, the US Army carried out extensive documentation of the bomb damage under the direction of the military commissioner for the Manhattan Project, General Leslie Groves , in which scientists and medics also took part. As far as published, however, the results were shaped by propaganda. Photos and film footage of damage and victims, which were first made by the Japanese, were confiscated and locked up. Likewise, the film and photo recordings of the damage and victims were declared top secret by the specially deployed Army Air Force troops and only handed over to the National Archives and Records Administration and released in the early 1980s . In particular, the radiological effect of the weapons, which claimed tens of thousands of victims months after the explosions, was also denied. It is estimated that in Hiroshima by the end of 1945 a further 60,000 initially survivors died from the effects of radiation, burns and other serious injuries. By 1950 the number of late victims in both cities had risen to a total of 230,000, most of them had fallen victim to the effects of primary radiation.

Today, the radiation exposure of the bombed areas is no longer above the level of normal background radiation (so-called natural radioactivity) and is therefore no higher than in other areas of the world.

Epidemiological Studies

The long-term effects of the bombs were documented in numerous epidemiological studies and the effects on selected organs were examined. The results of such studies are also taken into account when considering how to deal with nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl or Fukushima .

Political Consequences

On August 31, 1946, John Herseys published a detailed "Hiroshima" report on the effects of the atomic bomb, first in the New Yorker . He showed the concrete effects of the bombing and radiation on six people. This special edition met with a broad response in all media of the time and was soon published as a book. This started the public debate in the US about the pros and cons of using atomic bombs.

The use of atomic bombs was subsequently controversial. Many initiatives of the international peace movement , such as the participants in the Easter marches , the International Doctors Against Nuclear War and many others , also refer to the date of the drops . In Germany in 1957 there was the fight-the-atomic death movement against the planned nuclear armament of the Bundeswehr , a first broad extra-parliamentary opposition.

A peace movement also arose in Japan in the immediate post-war period. This also included a campaign initiated by housewives to outlaw nuclear weapons, in which 30 million signatures were collected. To this day, numerous Japanese artists and writers, especially Ōe Kenzaburō, have contributed to coming to terms with the horrors of war. In 1955, a Peace Memorial Park and a Peace Museum were set up in Hiroshima to commemorate the use of the atomic bomb, although the victims of other nations were given insufficient attention. The commemoration in Japan is also generally criticized for the fact that the massive Japanese war crimes are largely ignored. Critics say that these own crimes have not been dealt with, which contributes to the poor relationship between Japan and its neighbors.

In 1967, Prime Minister Eisaku Satō formulated the Three Non-Nuclear Principles , which constitute Japan's nuclear policy and which renounce the manufacture, possession or import of nuclear weapons. These were ratified by parliament in 1971.

The Japanese Defense Minister Kyūma Fumio resigned in 2007 after saying in a speech to students that the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki “could not have been avoided” because they “saved Japan from a fate like Germany” (meaning the division of Germany ) and hastened the surrender. Large parts of Japanese society, the media and the opposition had expressed their outrage and put pressure on the politician.

Historical discourse

Proponents of the drops

Proponents of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki argue, among other things, that

- Japan had already used biological and chemical weapons and was working on its own atomic bombs in the war against China. At the beginning of 1945 it was waiting for the necessary material that was to come from Germany by submarine.

- the atomic bombs made the otherwise inevitable invasion ( Operation Downfall ) unnecessary. This has saved the lives of an estimated quarter of a million Allied soldiers and several million Japanese.

The planned Operation Downfall consisted of two parts. The first part, Operation Olympic, envisaged a massive amphibious landing operation on the Japanese island of Kyushu . The second part, Operation Coronet, saw the most powerful invasion in human history in Tokyo Bay. A complete conquest of Japan was not expected until 1947 or 1948.

At the time of the use of nuclear weapons, the Japanese army had over 10,000 aircraft ready, which were ready to be piloted into ships by kamikaze pilots when the invasion began . Because the pilots were trained to pounce on aircraft carriers and troop transports with thousands of soldiers on board, the Allied losses would have been disproportionately large.

Before the Allied Army Planning Staff even knew of the existence of the atomic bomb project, in April 1945 they estimated the number of Allied casualties at 456,000, including 109,000 dead over a period of 90 days for Operation Olympic. After a further 90 days and the completion of Operation Coronet, a total of 1.2 million victims, including 267,000 dead. The number of Japanese fatalities is estimated at several million.

These figures seem all the more realistic when you consider that the conquest of the small Japanese island of Okinawa (see Battle of Okinawa ) with only 450,000 inhabitants among the US troops resulted in 12,510 dead and 39,000 wounded. The Japanese army lost 107,000 men. There were 42,000 to 122,000 dead among the civilian population, who threw themselves in the thousands from the white limestone cliffs. Not least because of the fierce resistance of the Japanese on Okinawa, the Allied planning staff reckoned with over a quarter of a million dead US soldiers and seven million dead Japanese soldiers and civilians when conquering the main Japanese islands, which are densely populated with 75 million people. So many casualties were expected that US factories had already made over 500,000 Purple Heart Wound Badges. More had already been ordered.

Opponent of the drops

As the first known historian, Gar Alperovitz questioned the justification of the US government for the drops. The rescue of Americans was only a pretext. The drops should not have avoided an invasion of Japan, but rather deterred the Soviet Union from advancing further into the Far East and demonstrated the power of the USA.

The expected losses in an invasion of the main Japanese islands in 1945 are questioned by various sources. According to historical research, the US losses were estimated to be much lower before the drops than afterwards: the military initially assumed that 25,000 to 46,000 US soldiers were killed in an invasion of Japan. Since Japan's surrender was foreseeable even without this and there were also other alternatives for ending the war, the official thesis that the use of the atomic bomb had saved the lives of many Americans is wrong. Some of the leading US military at the time, such as General Dwight D. Eisenhower , General Douglas MacArthur , Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy , General Carl Spaatz and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz , already believed that the atomic bombing was not militarily sensible or necessary .

Other researchers explain the drop orders by stating that the use was intended to justify the high development costs of the atomic bombs (two billion dollars) or to test their effectiveness on real targets. Racist motives are also mentioned, right up to the portrayal of the operations as genocide . In particular, according to Martin Sherwin, the use of the atom bomb in Nagasaki was "pointless at best, genocide at worst".

Barton Bernstein cites the following alternatives to the use of atomic bombs :

- waiting for the Soviet Union to enter the war

- a test demonstration of the atomic bomb either over uninhabited areas or against a military target

- Peace negotiations with negotiators

- changed surrender conditions

- another siege of Japan with conventional forces

According to Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Japan surrendered primarily not because of the use of atomic bombs, but because of the Soviet Union's entry into the war. Even the air strikes on Tokyo , which claimed more victims in two hours than the use of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, would not have had a decisive effect on ending the war.

Mediating position

Between opponents and supporters there are historians who try to understand the decision to drop the atomic bomb from the point of view of the US leadership at the time. They argue that

- the atomic bomb was then seen as a legitimate weapon in the fight against the enemy and this assumption was adopted unchecked by Truman.

- Truman saw the atomic bomb as a legitimate means to end the war quickly, to avoid possible future invasions and to punish Japan for Pearl Harbor , so that other alternatives were not even considered.

- the deterrence of the Soviet Union or the justification of the financing of the atomic bomb were important but secondary motives ( bonus ) for the use of the atomic bombs.

The best known representative of this camp is Barton J. Bernstein . Bernstein assumes two reasons why alternatives to the use of atomic bombs, which could have ended the war by November, were not chosen. First, from the US government's point of view, the Japanese appeared determined to continue fighting despite the hopeless situation (almost complete loss of Japanese armed forces, loss of raw materials), at least until the time of the planned invasion in November. Bernstein quotes Japanese leaders who stress Japan's absolute willingness to sacrifice up to 20,000,000 lives in the event of an invasion. The US leadership therefore saw the atomic bomb as an important and legitimate means to accelerate the end of the war or to avoid a landing, even if it had "only" cost 25,000 US lives.

Another main reason for using the atomic bomb, according to Bernstein, is that moral scruples were eroded in the USA towards the end of the war.

Rating in the USA

In the US today, the bombing is still often seen as justified. For example, US President George Bush senior said in 1991 that "the drops have saved millions of lives". J. Samuel Walker sees this public opinion shaped by school books that reduce the alternatives to ending the war to the use of atomic bombs or the invasion of Japan and also exaggerate the possible and probable numbers of US victims of an invasion.

The fact that some US historians are increasingly critical of the traditional justification for the drops since 1960 because of documents published by the US Air Force and diplomacy at the time has hardly influenced the general image of history. To date, no US government has issued an official apology to the civilian victims of the drops and their families.

The bomber pilot Paul Tibbets has never regretted the drop.

Rating in Japan

Immediately after the end of the war, all reports, photographs and film recordings about the consequences of the atomic bombing operations were subject to strict censorship by the US occupying forces. It wasn't until 1948 that details began to leak to the public. The way to come to terms with the Second World War is still controversial in Japan today. The atomic bomb attacks play an essential role in this. As a result of the war, Japan sees itself as responsible to be a peacemaking nation, but primarily thinks of its own victims. But even later, the Japanese government never officially protested against the atomic bombs, nor tried to sue the USA.

Commemoration

Hiroshima

The destroyed inner city of Hiroshima was rebuilt, only the central island in the Ōta river was preserved as a peace park. There are a number of memorials on the site, including a flame that is said to go out when the last atomic bomb is destroyed; today Bomb Dome -called ruin of the Chamber of Commerce ; the Peace Museum ; the Children's Peace Monument, commemorating Sasaki Sadako ; and a memorial for the Korean slave laborers who were killed.

Since August 6, 1947, Hiroshima has been commemorating the victims of the atomic bomb every year with a large commemoration ceremony. In the city's Peace Park, the peace bell is struck at exactly 8:15 a.m., the time of the drop .

On August 6, 2006, Japan's then Prime Minister Koizumi Jun'ichirō confirmed that his country would continue anti-nuclear policy. People in Hiroshima thought of the victims with calls for a world free of nuclear weapons. Survivors, relatives of victims, citizens and politicians observed a minute's silence while bells peal. In the post-war period, all of Hiroshima and Nagasaki mayors were active advocates for nuclear disarmament.

On May 26, 2016, Barack Obama became the first incumbent US president to visit the city. This visit should not be understood as an excuse for dropping the atomic bomb. Rather, he warns of the consequences of a new nuclear war and wants the world to learn lessons from Hiroshima.

Flame of Peace in Hiroshima Peace Park . In the background the Peace Museum

Shinzo Abe and Barack Obama in front of the cenotaph for the victims of the atomic bomb

Nagasaki

In Nagasaki, the atomic bomb museum and the peace park have been commemorating the consequences of the atomic bomb since 1955 . At Nagasaki University , the Atomic Bomb Disease Institute (created in April 1997 as a merger of the Atomic Disease Institute, founded in 1962 and the Scientific Data Center for the Atomic Bomb Disaster , founded in 1974 ) deals with the medical consequences of the explosion and the consequences of radioactive radiation in general . There is also the Oka Masaharu Memorial and Peace Museum of Nagasaki ( 岡 ま さ は る 記念 長崎 平和 資料 館 , Oka Masaharu Kinen Nagasaki Heiwa Shinryōkan ), where in particular about the prehistory of the war in relation to Japanese activities in other Asian countries, the fate of Korean and Chinese Forced laborers and other victims in Japanese pre-war and war history are reported and informed.

Entrance to the atomic bomb museum

Memorial ceremony in Nagasaki Peace Park

Documentaries

- Hiroshima, Nagasaki - Atomic bomb victims testify. 90 min. Production: ZDF . A documentary by Hans-Dieter Grabe . Germany 1985.

- 1945 - the bomb. (= 100 years - The countdown . Episode 44). 10 min. Production: ZDF. Germany 1999.

- Hiroshima. (= Days that moved the world. Season 1, episode 4). 50 min. Production: BBC . A documentary by Stephan Walker. UK 2003.

- Hiroshima - The day after. 50 min. Production: Tower Productions. USA 2008.

- Nagasaki - The Forgotten Bomb. (= Seconds before the accident . Season 6, episode 8). 60 min. Production: National Geographic Society . German premiere: July 29, 2013.

- Countdown to a new age: Hiroshima. 94 min. Production: Brook Lapping Productions. A documentary by Lucy van Beek. UK 2014.

- Nagasaki - Why did the second bomb fall? 45 min. Production: NDR . A documentary by Klaus Scherer . Germany 2015.

- When the sun fell from the sky - A search for clues in Hiroshima. 78 min. Production: Ican Films in cooperation with SRF . A documentary by Aya Domenig . Switzerland 2015.

- Hiroshima 1945. (= traces of the war. Part 4). 44 minutes. A documentary by Marie Linton and Thibaut Martin. Germany / France 2016.

- Hiroshima - Chronicle of a Tragedy. 58 min. Post production by Studio Hamburg Synchron GmbH for ZDF History . A documentary by Paul Wilmshurst. German premiere: August 2, 2020.

literature

Victim and contemporary witness reports

- Takashi Nagai : The bells of Nagasaki. 9th edition. Translated by Friedrich Seizaburo Nohara. Verlag Schroeder, Kleinjörl near Flensburg 1980, ISBN 3-87721-034-1 . (Completed 1946, first edition in Germany 1956 by Rex-Verlag Munich) (The author describes - as a person affected - the atomic bomb drop on Nagasaki, its effects and later health consequences from the perspective of a radiologist)

- Günther Anders The man on the bridge. Diary from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (= Beck's Black Series. Vol. 3). 2nd, revised edition. Beck, Munich 1963.

- Eric Chivian et al. a. (Ed.): Last Aid. The medical effects of nuclear war. = Last help. International Doctors for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Jungjohann Verlagsgesellschaft, Neckarsulm 1985, ISBN 3-88454-777-1 (including contemporary witness Michito Ichimari in Nagasaki and psychological effects in Hiroshima and medical effects in Hiroshima and Nagasaki).

- Helmut Erlinghagen : Hiroshima and us. Eyewitness reports and perspectives (= Fischer. 4236). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-24236-3 .

- Gerd Greune , Klaus Mannhardt (eds.): Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Images, texts, documents. Pahl-Rugenstein, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-7609-0636-2 .

- Michihiko Hachiya : Hiroshima Diary. The Journal of a Japanese Physician, August 6 - September 30, 1945. Fifty Years later. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC a. a. 1995, ISBN 0-8078-4547-7 . (Diary of a doctor who was in town during the bombing, for months afterwards)

- John Hersey : Hiroshima. August 6, 1945, 8:15 am With a foreword by Robert Jungk . European publishing company, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-434-50596-2 . (Report by an American journalist shortly after the occupation began with interviews with survivors)

- Ibuse Masuji : Black Rain (= Fischer. 5846). Unabridged edition. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-25846-4 .

- Keiji Nakazawa : Barefoot through Hiroshima . 4 volumes. Carlsen, Hamburg 2004–2005. (Internationally awarded manga series by an eyewitness)

- Toyofumi Ogura: Letters from the End of the World. A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima. 1st paperback edition. Kodansha, Tokyo et al. a. 2001, ISBN 4-7700-2776-1 .

- Kyoko I. Selden, Mark Selden: The Atomic Bomb. Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan in the Modern World. Sharpe, Armonk NY, et al. a. 1989, ISBN 0-87332-773-X .

- Charles W. Sweeney , James A. Antonucci, Marion K. Antonucci: War's End. An Eyewitness Account of America's Last Atomic Mission. Avon Books, New York NY 1997, ISBN 0-380-97349-9 .

- Hermann Vinke (Ed.): When the first atomic bomb fell ... Children from Hiroshima report. Otto Maier, Ravensburg 1982, ISBN 3-473-35067-2 (Original edition: Arata Osada (Ed.): Genbaku no Ko.Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo 1951).

prehistory

- William Craig: The Fall of Japan. Dial Press, New York NY 1967.

- Robert Jungk: Brighter than a thousand suns. The fate of atomic researchers (= Heyne-Bücher 19, Heyne-Sachbuch 108). 3. Edition. Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-04019-8 .

- William L. Laurence : The History of the Atomic Bomb. Twilight over point zero. List, Munich 1952.

- Paul Takashi Nagai : The Bells of Nagasaki. History of the atomic bomb. Rex-Verlag, Munich 1955.

- Richard Rhodes: The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster, New York NY a. a. 1986, ISBN 0-671-65719-4 .

- Gordon Thomas , Max Morgan Witts: Enola Gay. Stein and Day, New York NY 1977, ISBN 0-8128-2150-5 .

- Stephen Walker: Hiroshima - Countdown to Disaster. Translated from the English by Harald Stadler. Bertelsmann, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-570-00844-7 .

Historical context

- Florian Coulmas : Hiroshima. History and post-history (= Beck's series. Vol. 1627). Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52797-3 .

- Richard B. Frank: Downfall. The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin Books, New York NY et al. a. 2001, ISBN 0-14-100146-1 .

- Michael J. Hogan (Ed.): Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge 1996, ISBN 0-521-56206-6 .

- Fletcher Knebel , Charles W. Bailey II: No High Ground. Harper, New York NY 1960.

- Cay Rademacher : Attack on Asia: Hiroshima. In: Michael Schaper (Ed.): End of the war 1945. The finale of the world fire. (= GEO epoch. No. 17). Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-570-19555-0 , pp. 112-130.

- Pacific War Research Society: Japan's Longest Day. Kodansha International Ltd., Tokyo 1968.

- Gordon Thomas, Max Morgan Witts: Death over Hiroshima. World history was shaped by a bomb. Bergh in the Europabuch-AG, Unterägeri (Zug) 1981, ISBN 3-7163-0131-0 .

- J. Samuel Walker: Prompt and Utter Destruction. Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC u. a. 1997, ISBN 0-8078-2361-9 .

- Stanley Weintraub: The Last Great Victory. The End of World War II, July / August 1945. Dutton, New York NY 1995, ISBN 0-525-93687-4 .

backgrounds

- Gar Alperovitz: The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. And the Architecture of an American Myth. Knopf, New York NY 1995, ISBN 0-679-44331-2 (in German: Hiroshima. The decision to drop the bomb. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-930908-21-2 ).

- Thomas B. Allen, Norman Polmar: Code-Name Downfall. The Secret Plan to invade Japan and why Truman dropped the Bomb. Simon & Schuster, New York NY a. a. 1995, ISBN 0-684-80406-9 .

- Barton J. Bernstein (Ed.): The Atomic Bomb. The Critical Issues. Little, Brown, Boston MA 1976.

- Claus Biegert (Ed.): The Monday that changed the world. Reading book of the atomic age (= Rororo 13939 rororo current. Rororo current ). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-499-13939-1 .

- Kathrin Dräger: Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the endpoints of a conflict escalation. A contribution to the debate about the atomic bombs. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8288-2045-6 .

- Richard B. Frank: Why Truman Dropped the Bomb: Sixty years later, we have the secret intercepts that shaped his decision. In: The Weekly Standard . August 8, 2005, p. 20.

- Paul Fussell : Thank God for the Atom Bomb and other essays. 1st Ballantine Books edition. Ballantine, New York NY 1990, ISBN 0-345-36135-0 .

- Robert Jay Lifton , Greg Mitchell: Hiroshima in America. A half century of denial. Avon Books, New York NY 1996, ISBN 0-380-72764-1 .

- Robert James Maddox: Weapons for Victory. The Hiroshima Decision fifty years later. University of Missouri Press, Columbia MO et al. a. 2004, ISBN 0-8262-1037-6 .

- Philip Nobile (Ed.): Judgment at the Smithsonian. Marlowe and Company, New York NY 1995, ISBN 1-56924-841-9 (controversy about the exhibition planned for 1995 at the Smithsonian Institution , which was eventually canceled).

- Klaus Scherer : Nagasaki. The myth of the decisive bomb. Hanser, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-446-24947-9 .

- Ronald T. Takaki : Hiroshima. Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown, and Co., Boston MA 1995, ISBN 0-316-83124-7 .

- Shigetoshi Wakaki: Hiroshima. The infamous maximization of a mass murder. The first report by an expert and an eyewitness. Grabert, Tübingen 1992, ISBN 3-87847-121-1 .

consequences

- Peter Bürger : Hiroshima, the war and the Christians. Fiftyfifty, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-9807400-7-2 .

- Angelika Jaeger (translator): Life after the atomic bomb. Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945–1985. Committee to Document the Damage from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1988, ISBN 3-593-33852-1 .

- Robert Jungk (Ed.) Off limits for the conscience. The correspondence between the Hiroshima pilot Claude Eatherly and Günter Anders (= Rowohlt-Paperback. Vol. 4). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1961.

- Takashi Nagai: We were there in Nagasaki. Metzner, Frankfurt am Main 1951.

- Robert P. Newman: Truman and the Hiroshima Cult. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing MI 1995, ISBN 0-87013-403-5 (critical analysis of the postwar opposition to the bomb).

- Takeshi Ohkita: Acute Medical Impacts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In: Eric Chivian et al. a. (Ed.): Last Aid. The medical effects of nuclear war. = Last help. International Doctors for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Jungjohann Verlagsgesellschaft, Neckarsulm 1985, ISBN 3-88454-777-1 , pp. 69-92.

- Gaynor Sekimori (translator): Hibakusha. Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Kōsei Publishing Company, Tokyo 1986, ISBN 4-333-01204-X .

- Robert Trumbull: How They Survived. The Report of the Nine of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf 1958.

Web links

- Atomic Bomb Drop on Hiroshima - Online Exhibition at Google Arts & Culture (English)

- Atomic bombing of Nagasaki - online exhibition at Google Arts & Culture (English)

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum official website (English, Japanese)

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum Official Website (English, Japanese)

- Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered (English)

- The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki . In: The Public's Library and Digital Archive

- Literature by and about the atomic bombing on Hiroshima in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about the atomic bombing on Nagasaki in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b David Horowitz , Cold War. P. 46.

- ↑ Chris Hastings: UK proposed using atom bomb against Germany , The Age , December 2, 2002, accessed August 6, 2010.

- ↑ Minutes of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945 (minutes of the meeting, English)

- ↑ Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting, Friday, June 1, 1945 (photocopy of the original documents, English)

- ↑ Bard Memorandum, June 27, 1945 (English)

- ↑ David Horowitz: Cold War. P. 45.

- ^ Winston S. Churchill: Triumph and Tragedy. Pp. 638-639. (English)

- ^ Theo Sommer: 1945. The biography of a year. Pp. 179-186.

- ↑ Harry S. Truman's diary entry on the deployment order, July 25, 1945 (English); Operation order from Chief of Staff General Handy to General Spaatz, Commander of the Strategic Air Force, July 25, 1945 (English)

- ↑ Debate over how to use the bomb ( Memento from September 28, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Potsdam Declaration, July 26, 1945 (English)

- ^ The Information War in the Pacific, 1945. Retrieved November 11, 2010 .

- ^ Decision to Drop Atomic Bomb. ( Memento from February 5, 2009 in the web archive archive.today ) Cia.gov

- ↑ The Myths of Hiroshima. ( Memento of May 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Commondreams.org

- ↑ Hiroshima: Historians' Letter to the Smithsonian. Doug-long.com, accessed March 25, 2009 .

- ^ Theo Sommer: 1945. The biography of a year. P. 189.

- ↑ quoted from Theo Sommer: Decision in Potsdam . In: Die Zeit , No. 30/2005, p. 78.

- ↑ Timeline # 2 - The 509th; The Hiroshima Mission ( Memento from October 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ William L. Lawrence: Twilight Above Zero Point. The history of the atomic bomb. List Verlag, Leipzig / Munich 1952, pp. 182-183; quoted from Helmut Gollwitzer: The Christians and the nuclear weapons. 6th edition. Unchanged reprint of the 1st edition 1957. Christian Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-459-01407-5 , p. 7.

- ↑ Eric Schlosser: Command and Control: the US nuclear arsenals and the illusion of security. CH Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65595-1 .

- ↑ Tom Mathewson: A Strange Turn - Why leave the atomic target at a 155 degree heading?

- ↑ Louis Allen: The Nuclear Raids Article - History of the Second World War . Purnell, 1969.

- ↑ Timeline # 2- the 509th; The Hiroshima Mission. The Atomic Heritage Foundation, accessed May 5, 2007 .

- ^ DOE Office of History & Heritage Resources: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima. Aug 6, 1945 .

- ^ Robert Siegel and Melissa Block (National Public Radio, Nov. 1, 2007): Pilot of Enola Gay Had No Regrets for Hiroshima .

- ^ Harry S. Truman, Library & Museum. US Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 19, 1946. President's Secretary's File, Truman Papers. 2. Hiroshima. P. 11 of 51. Retrieved on March 15, 2009.

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions # 1. Radiation Effects Research Foundation , archived from the original on September 19, 2007 ; Retrieved September 18, 2007 .

- ↑ Chapter II: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings. In: United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Originally by USGPO ; stored on ibiblio .org, 1946, accessed September 18, 2007 .

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions # 2. Radiation Effects Research Foundation , archived from the original on November 28, 2010 ; Retrieved November 11, 2010 .

- ↑ trove.nla.gov.au

- ↑ ourcivilization.com

- ↑ Gordon Thomas, Max Morgan Witts: Death over Hiroshima. ISBN 3-7163-0131-0 , p. 476.

- ↑ Both of the above quotes after atomic bombs were dropped in Japan: Nagasaki went under due to a lack of fuel . Spiegel Online , April 22, 2005

- ^ Greg Mitchell: Atomic Cover-Up: Two US Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and The Greatest Movie Never Made . Sinclair Books, New York 2011, chapter “Nagasaki”.

- ^ Rainer Werning: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the forgotten Koreans .

- ^ Greg Mitchell: Atomic Cover-Up: Two US Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and The Greatest Movie Never Made . Sinclair Books, New York 2011, p. 101.

- ↑ Video of the preparations for the launch of the Nagasaki bomb on youtube.com from 0:20

- ↑ Nagasaki went under due to a lack of fuel (2). Spiegel Online , April 22, 2005.

- ↑ Takeshi Ohkita: Acute Medical Effects in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. P. 85.

- ↑ nuclear A-Z .

- ↑ Stern (magazine): Nagasaki remembers its victims .

- ^ Overview of the Nagasaki University School of Medicine ( Memento of March 29, 2002 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Quoted from Theo Sommer: 1945. The biography of a year. Hamburg 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Greg Mitchell: Atomic Cover-Up: Two US Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and The Greatest Movie Never Made . Sinclair Books, New York 2011.

- ^ Q&A about the Atomic Bombing (Hiroshima City website) ( July 1, 2003 memento in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ K. Kamiya, K. Ozasa, S. Akiba, O. Niwa, K. Kodama, N. Takamura, EK Zaharieva, Y. Kimura, R. Wakeford: Long-term effects of radiation exposure on health. In: Lancet. 386 (9992), Aug 1, 2015, pp. 469-478, Review. PMID 26251392 .

- ↑ R. Sakata, EJ Grant, K. Furukawa, M. Misumi, H. Cullings, K. Ozasa, RE Shore: Long-term effects of the rain exposure shortly after the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In: Radiat Res. 182 (6), Dec 2014, pp. 599-606. PMID 25402555 .

- ↑ M. Imaizumi, W. Ohishi, E. Nakashima, N. Sera, K. Neriishi, M. Yamada, Y. Tatsukawa, I. Takahashi, S. Fujiwara, K. Sugino, T. Ando, T. Usa, A Kawakami, M. Akahoshi, A. Hida: Association of radiation dose with prevalence of thyroid nodules among atomic bomb survivors exposed in childhood (2007-2011). In: JAMA Intern Med. 175 (2), Feb 2015, pp. 228-236. PMID 25545696 .

- ↑ H. Sugiyama, M. Misumi, M. Kishikawa, M. Iseki, S. Yonehara, T. Hayashi, M. Soda, S. Tokuoka, Y. Shimizu, R. Sakata, EJ Grant, F. Kasagi, K. Mabuchi, A. Suyama, K. Ozasa: Skin cancer incidence among atomic bomb survivors from 1958 to 1996. In: Radiat Res. 181 (5), May 2014, pp. 531-539. PMID 24754560 .

- ↑ A. Hasegawa, K. Tanigawa, A. Ohtsuru, H. Yabe, M. Maeda, J. Shigemura, T. Ohira, T. Tominaga, M. Akashi, N. Hirohashi, T. Ishikawa, K. Kamiya, K Shibuya, S. Yamashita, RK Chhem: Health effects of radiation and other health problems in the aftermath of nuclear accidents, with an emphasis on Fukushima. In: Lancet. 386 (9992), Aug 1, 2015, pp. 479-488, Review. PMID 26251393 .

- ^ John W. Dower, The Bombed - Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Memory , Diplomatic History 1995.

- ^ Per F. Dahl: Heavy water and the wartime race for nuclear energy . CRC Press, 1999, ISBN 0-7503-0633-5 , pp. 279-285 .

- ^ Bowen C. Dees: The Allied Occupation and Japan's Economic Miracle: Building the Foundations of Japanese Science and Technology 1945–1952 . Routledge, 1997, ISBN 1-873410-67-0 , pp. 96 .

- ^ Zbynek Zeman, Rainer Karlsch: Uranium Matters: Central European Uranium in International Politics, 1900-1960 . Central European University Press, 2008, ISBN 963-9776-00-9 , pp. 15 .

- ↑ a b c Frank: Downfall. Pp. 135-137.

- ^ Skates: The Invasion of Japan. P. 37.

- ^ Spector, 276-277.

- ↑ a b Frank: Downfall. P. 340.

- ↑ Dennis M. Giangreco, Kathryn Moore: Are New Purple Hearts Being Manufactured to Meet the Demand? History News Network. (December 1, 2003), Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- ^ Gar Alperovitz: Atomic Diplomacy. 1965.

- ^ Samuel Walker: Prompt and Utter Destruction: President Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan . University of North Carolina Press, 2005 (revised edition).

- ^ Statements by high US military officials .

- ^ P. Joshua Hill, Professor Koshiro, Yukiko: Remembering the Atomic Bomb. FreshWriting December 15, 1997.

- ↑ An experiment with 70,000 dead . Zeit Online , 2009

- ↑ Quoted from Bruce Cumings: Parallax Visions. Duke 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ Barton J. Bernstein: Understanding the Atomic Bomb and Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory. Hiroshima in History and Memory. University of Cambridge Press, New York 1996.

- ↑ Tsuyoshi Hasegawa: Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2005.

- ↑ Barton J. Bernstein: "Understanding the Atomic bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory", 'Diplomatic History' 1995.

- ↑ Joshua / Hill: Remembering the Atomic Bomb ( Memento of July 29, 2003 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ J. Samuel Walker: History, Collective Memory, and the decision to use the Bomb. Diplomatic History 1995.

- ↑ Atomic bomb on Hiroshima - The unrepentant mass murderer . Spiegel Online ; Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ^ Regine Mathias (ARD, August 5, 2005): Japan sees itself primarily as a victim ( Memento of October 28, 2005 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Florian Coulmas: Hiroshima and Nagasaki: About the first and only use of the atomic bomb sixty years ago . In: NZZ , August 9, 2005

- ^ ARD report on the 70th anniversary (2015) - accessed on March 2, 2016.

- ↑ Small calendar: “Hiroshima Memorial Day”, accessed on March 2, 2016.

- ^ Obama's delicate Hiroshima mission. Spiegel Online , May 26, 2016.

- ↑ Felix Lee: Obama's Lessons from Hiroshima. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , 28./29. May 2016, p. 4.

- ↑ Hiroshima, Nagasaki - Atomic bomb victims testify. In: Programm.ARD.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ 1945 - The bomb. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Days That Moved the World: Hiroshima. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Hiroshima - The Day After. In: Welt.de. Retrieved August 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Nagasaki - The Forgotten Bomb. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Countdown to a new age: Hiroshima. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Nagasaki - Why did the second bomb fall? In: Programm.ARD.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ When the sun fell from the sky - A search for clues in Hiroshima. In: Programm.ARD.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Website for the documentary film When the sun fell from the sky

- ↑ Hiroshima 1945. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Hiroshima - Chronicle of a Tragedy. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved August 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwentker: Review of Florian Coulmas: Hiroshima. History and post-history on H-Soz-u-Kult, August 26, 2005.

- ↑ Alan Posener : Unheimliche Stille , Review, in: August 1, 2015, p. 4 (Posener criticizes Scherer's uncritical adoption of the theses of the revisionist historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa).