Boreal coniferous forest

| Boreal coniferous forest | |

|

Boreal coniferous forest on the Yukon River in Alaska |

|

| Area share | approx. 9% of the land surface |

| Ecological condition | > 30% original wilderness <40% largely near-natural |

| Land use | Forestry, stationary livestock farming, arable farming with fast-ripening crops, nomadic (reindeer) grazing |

| biodiversity | low to high (1,500–3,000 species per hectare) |

| Biomass | medium (100–300 t / ha dry matter) |

| Representative large protected areas (only IUCN Ia, Ib, II , NP , WE and PP ) |

Wood Buffalo (CAN) 44,807 km² Wabakimi (CAN) 8,920 km² |

|

Climatic conditions

Boreal coniferous forest : climate diagrams |

|

| Exposure to sunlight | <800–1200 kWh / m² / a (for the zone) |

| Ø temperatures |

Coldest month: below 0 to below −40 ° C Annual mean: below −10 to above 5 ° C Warmest month: above 5 to 20 ° C |

| Annual precipitation | <200–> 900 mm (5–7 months of snow) |

| Water balance | semi-humid to humid |

| Growing season | 90-180 days |

Boreal coniferous forest (from Greek Βορέας Boréas , German 'the northern one' : god of the north wind in Greek mythology), also taiga (from Russian тайга , dense, impenetrable, often swampy forest ' , possibly derived from Mongolian тайга , mountain forest' ) is the Generic term for the forests of the cold temperate climatic zone . The taiga occurs without exception in the northern hemisphere, as the southern hemisphere lacks the large land masses that allow the climate typical of the boreal forests. The term comes from geography and generally designates a certain type of landscape on the global scale . There are different definitions depending on the discipline, see section “Definition” .

Characteristic for the different forms of boreal forests are relatively uniform coniferous forest areas , which are characterized by only four types of coniferous wood worldwide - spruce , pine , fir and larch - whose growth pattern becomes increasingly slender towards the north. These areas are interrupted in the lowlands by tree-free moors (very large in western Siberia), in northern Asia by softwood meadows in the river valleys and in north-eastern Siberia larch forest tundra and larch taiga alternate like a mosaic. Softwoods - especially birch and aspen - can be found as pioneer tree species and in protected locations almost everywhere in the coniferous forest. The ground is mostly covered by relatively low-growing, deciduous dwarf shrubs (especially from the blueberry genus) and by thick “carpets” of moss and lichen. Deadwood is found in large quantities in all stages.

definition

From the perspective of Geobotany (plant geography) of the boreal forest is a natural vegetation type , which especially under the conditions of snow-forest climate is created. In their erdumspannenden ( geozonalen ) expansion include boreal forests to the vegetation zones .

From the point of view of ecology , the boreal coniferous forest is one of the largest possible (abstract) ecosystems that together form the biosphere . It itself is formed from typical biomes or ecoregions , which in turn are composed of the associated small-scale (specific) biotopes and ecotopes . These in turn subdivide the Earth-encompassing boreal-polar zono-ecoton or the boreal eco-zone .

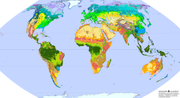

Spread and condition

The boreal coniferous forest is an exclusively northern vegetation zone. Its maximum extent extends from about 71 ° north latitude (upper reaches of the Olenjok in northern Siberia) to 42 ° (on the Japanese island of Hokkaidō ). The boreal coniferous forests merge towards the pole into the forest tundra zone . (The representation of the forest tundra as an independent vegetation type - as done here in Wikipedia - is inconsistent: in some publications it is instead counted as boreal forests, in some as tundra.) In the direction of the equator, the mixed coniferous and deciduous forests close in wetter climates the taiga on and in drier climates the forest steppes .

Many mountain coniferous forests of the subalpine altitude level of other climatic zones resemble the boreal coniferous forest. However, they are mostly viewed as a separate vegetation zone.

Boreal coniferous forests are located in Eurasia ( Northern Europe (" Northern European Coniferous Forest Region "), Siberia , Mongolia ) and North America ( Canada , Alaska ). With around 1.4 billion hectares, they are the largest contiguous forest complex on earth and the most economically important forest region. Of this area, however, around 150 million hectares are temporarily not forested due to fire, storms, large-scale insect damage or human activities.

The largest undestroyed boreal wilderness area on earth stretches from the Yukon Territory in Canada to the central reaches of the Yukon River in Alaska. Coniferous forests, open lichen forests, forest tundras and Nordic deciduous forests stand here in a closely interlinked mosaic on a mountainous landscape rich in structures. The largest contiguous boreal coniferous forest wilderness covers the West Siberian lowlands far into the Central Siberian highlands . In Europe, too, there are still significant, largely untouched boreal primeval forests. Most of them are in northwestern Russia and a small part in Finland and Scandinavia. All in all, they cover an area larger than the United Kingdom . However, they are already clearly fragmented.

In relation to the potential natural vegetation , around 9% of the terrestrial land surface today are boreal coniferous forests. In fact, at the beginning of the 3rd millennium, over 30% of the boreal coniferous forests are in a largely unaffected natural state . These areas are almost uninhabited. Less than 40% are still close to nature and have relatively little influence. However, these areas are mostly highly fragmented and are consistently changing (either through constant conversion into usable areas or through overexploitation ). In over 30% the original vegetation cover has been intensively changed and shaped by anthropogenic landscapes . In these areas, near-natural taiga landscapes are only to be found in small relics.

Characteristic

The appearance of a boreal coniferous forest is fundamentally different from that of the planted coniferous forests of the temperate zone. While forest trees are very dense for many years, the taiga forests - apart from a few scattered, dense groups of trees - are much lighter. To protect against damage from the snow load, the shape of the trees becomes increasingly slender towards the north. A dense branch down to the ground ensures optimal use of light and heat from the low-lying sun. In commercial forests, on the other hand, the branches are bare right up to the crowns. In addition, almost all trees are of the same age group , in contrast to the mostly random juxtaposition of all ages in the taiga forest. Another obvious contrast to the forest is the undergrowth of a naturally grown boreal coniferous forest: Instead of a largely open needle litter cover, the ground is covered with dwarf shrubs (especially blueberries) and mosses, which often lie close to the ground ( trellis-like ). In addition, there is a large amount of lying and standing deadwood , which is in all stages of rotting (20 to 30% standing deadwood is characteristic in natural forests). Ultimately, the forest floors of untouched boreal forests show a decidedly "humpbacked" relief due to the dead wood, the often rocky subsoil, but above all due to the lack of human activity.

The boreal coniferous forest is characterized by only four species of coniferous wood and often has only one or two tree species in its core areas. It is therefore one of the species-poor forests. This is primarily due to the short growing season of only three to six months; therefore a low energy input into the ecosystem. However, the last Ice Age also played a role: In North America and East Asia, the geographical and climatic conditions for the species to move south and for the later return migration were much more favorable than in Eurasia, so that the range of species there today is somewhat larger.

The main reason for the dominance of evergreen conifers is the fact that it all year with a fully equipped photosynthetic apparatus (i. E. Needles ) have, while deciduous trees every year (also at high nutrient requirements) need to develop new leaves. The photosynthetic activity of the perennial needles only stops as long as the needles are frozen below −4 ° C. At higher temperatures, it starts again immediately without any loss of time. As the length of the vegetation period decreases, the metabolism of deciduous tree species becomes more and more uneconomical. (A threshold value is the number of at least 120 days per year on which the mean daily temperature exceeds 10 ° C.) Only a few softwoods (especially birch and aspen) can hold their own in a boreal climate.

Most conifers can also withstand temperatures as low as −40 ° C. In Yakutia , average temperatures of −50 ° C or less are possible. In this extreme climate, however, it is too cold for even most conifers. Only the needle-shedding larches ( Larix spec. ) Can thrive here. It was only thanks to their ability that a forest was able to develop in areas with a clear tundra climate and where there is permanent ground frost. Because of the needle-shedding larch trees in Russia, it is called the “light taiga” - in contrast to the “dark taiga”, which is dominated by the evergreen conifers.

The vegetation endures a cold period of eight months. The xeromorphic foliage of the evergreen conifers (with the exception of the larches) is - as already described - much less sensitive to cold and frost-drought than the leaves of the deciduous trees. The small surface, sunken stomata and a particularly thick cuticle (wax layer) protect them from the cold. The photosynthetic activity ceases at -4 ° C when the needles to freeze, but continue at higher temperatures again. The importance of temperatures increases the further the forests reach north or from oceanic to continental regions. Nevertheless, the Nordic conifers also have to go through the hardening process in autumn in order to survive the winter unscathed.

"Softening" takes place in spring. This is based on an increase in the sugar concentration in the cell sap. Other protective substances are accumulated in the protoplasm , the cells become less watery and the central vacuole fissures into a multitude of small vacuoles. The heat adaptation is quick, as the temperature rise can occur within a day, sometimes even faster. On hot days, the heat resistance is higher in the afternoon than in the morning. Softening in cool weather takes place within a few days. The hardening temperatures must be so high that they act as stress on the protoplasm. For most land plants, this is usually the case from 35 ° C.

Another important protection against the cold is the isolation of the roots by a blanket of snow, which keeps the temperature on the ground at around 0 ° C even in extremely freezing temperatures. Here, too, the larch is a survivor, as in the extremely dry continental areas of north-east Siberia there is often so little snow that no continuous snow cover is created. The roots of the taiga trees are - especially in the area of permafrost - extremely flat. Around 70–90% of the root mass extends to depths of 20–30 cm, and in more northerly areas the entire root mass is even concentrated in this thin soil zone.

Most of the boreal coniferous forests are interspersed with swamps and bogs. In damp places, the raw humus and the peat moss that settle on it slowly grow into high bogs . This insulates the subsoil so that it is more difficult for the soil to thaw in spring. In addition, the mosses store the nutrients and inhibit the function of the symbiosis between trees and fungi, and the soil becomes increasingly acidic. All of this makes the conditions worse for the trees, which eventually die. In the West Siberian Plain, such largely tree-free Taigamoore occupy hundreds of thousands of square kilometers.

Delimitation to the forest tundra

The conifers of the dark taiga are 15 to 20 meters high, the larches of the light taiga are only around eight meters and the stunted trees of the forest tundra are only four to six meters high.

As already described, the forest tundra is not differentiated from the boreal coniferous forest in many considerations - or only “in a subordinate clause” - although this type of vegetation no longer clearly corresponds to the definition of forest . The reason for this lies in the many exceptions that make it difficult to define it as an independent type:

- While the forest tundra still grows extensively on permafrost , this no longer applies to the northern coniferous forests - with the exception of eastern Siberia. The proportion of permanently frozen areas is decreasing towards the south.

- It is at least approximately possible for the boreal zone a climatic timber line to determine and thus the resolution of the forest zone up to the absolute tree line. However, the larch taiga of Central and Eastern Siberia is so light and rich in undergrowth everywhere that this is much more difficult here. Even in the southern boreal areas, the appearance of the forest is more reminiscent of a forest tundra.

- The large open lichen forests of Canada and Alaska still give the impression of a forest. The frequently occurring vegetative reproduction and the, in contrast, strongly restricted sexual reproduction via seedlings, as well as the poor regenerative capacity of these "forests" are clear characteristics of the forest tundra. Since the formation of the open lichen forests 9,500 to 7,500 years ago, the tree line has shifted further and further south, so that no real forest would potentially emerge in these areas today.

- The birch forests of Fennos Scandinavia or Kamchatka are known as birch forest taiga or birch forest tundra . On the one hand, they can certainly be addressed as forests in large areas ; on the other hand, the birches in these areas form the tree line, so that the main criterion for the forest tundra is given.

(The representation in Wikipedia counts the sparse Siberian larch forests as the taiga and the open lichen forests of North America as well as the areas dominated by deciduous trees as the forest tundra.)

Climatic conditions

The earth's boreal coniferous forests are located in the cold-temperate climate zone and are therefore usually characterized by cold climates with long, snowy winters and short, relatively cool summers. In the coldest month, average temperatures drop below 0 ° C, with the minimum being below -40 ° C. There is snow for five to seven months. The warmest month averages over 5 to 20 ° C; however, the temperature can easily rise above 30 ° C in summer. The long-term average temperature is below −10 to over 5 ° C.

The boreal zone begins in the south where the climate is too unfavorable for hardwood deciduous trees , i.e. H. where the number of days with daily mean temperatures above 10 ° C is below 120. For the boreal coniferous forests, there is also a low level of solar radiation , which makes plant growth more difficult , but this is partly compensated by the midnight sun in midsummer . The vegetation can withstand a cold period of a maximum of eight months.

With average values of less than 200 to over 900 mm, the total annual rainfall is low to medium. In the very continental part of the boreal climate zone, annual precipitation is 150–250 mm per year. The daily mean temperatures rise to over 10 ° C on 50 to 100 days. In oceanic areas - such as Scandinavia or Kamchatka - the precipitation is about twice as high, while the monthly mean temperature is not below −10 ° C even in the coldest month.

The long period of frost and low temperatures lead to a low evaporation rate, so that the climatic water balance on the ground semihumid (relatively moist) to humid (wet) is.

The growing season is relatively short at 90 to 180 days.

According to the effective climate classification by Köppen / Geiger, the conditions mentioned above are referred to as the so-called snow-forest climate (abbreviation: D).

Further characteristics

Floors

Frost plays a major role in soil formation in boreal forests. Particularly in the permafrost regions of Eastern Siberia with their continental climate, the alternating freezing and thawing leads to small depressions and elevations that shape the relief and can form different patterns. These so-called frost pattern soils are, however, much rarer and less pronounced here than in forest tundra and tundra. Mineral permafrost soils are called cryosols in the international soil classification World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) . They make up almost 50% of all taiga soils in Siberia.

Under the cold and wet conditions in the oceanic part of the boreal climate zone, the resulting litter is hardly worked into the mineral soil by animals and only slowly decomposed by bacteria and fungi. Over time, a thick layer of raw humus forms . Nutrients are only released slowly through mineralization and are poorly available to plants. The abundant acids mobilize iron and aluminum from the upper mineral soil and finally also organic substances, which accumulate again in lower soil horizons . This creates podsoles that are unfavorable for plant growth. Real podsols are found mainly in Northern Europe and Eastern Canada.

Organic soils, which are called histosols in the WRB, are also widespread . They usually have thick peat horizons and occur partly with and partly without permafrost. Shallow soils over solid rock and soils with a lot of skeleton are called leptosols . Large areas are covered by groundwater and backwater, the gleysols and stagnosols .

Podsols, Stagnosols, Leptosols and Histosols are each represented with 10%.

The soil litter is moderate and decomposition is very slow.

The world's largest reserves of peat (about 3/4 of the deposit) are in Russia.

Due to the abiotic factors mentioned above , the amount of biomass available is medium (100–300 t / ha dry matter). Every year 5–6 t / ha are created.

Fire

Fire and forest fires play an important role in the ecosystem and the development dynamics of boreal forests. The reason lies in the thick litter that prevents the forests from rejuvenating. The seeds of the trees do not make contact with the ground, where the available nutrients are and they could take root. The mineral soil is exposed again by fire. At the same time, the nutrients stored in the organic matter are released (a large part of them is lost again later through washing out). Fires are regular, natural occurrences in this ecosystem. The period between two fire events on a surface is described by the term fire rotation . In summer dry areas of Alaska and Canada this is 50 to 100 years, in wetter areas 300 to 500 years. In natural circumstances, fires are triggered by lightning strikes. In recent times, exceptionally dry periods have led to an increase in forest fires due to climate change .

flora

The biodiversity of the flora in the boreal zone - compared to more southern ecosystems - is low. By far the most common are conifers from the pine family (with the genera spruce, pine, fir and larch). In total, there are only twenty different tree species in the taiga areas. No other type of forest is so poor in tree species.

The superordinate plant community is formed by the "soil acidic coniferous forests and dwarf shrub communities" ( Vaccinio-Piceetae ). In the tree layer in western Eurasia one finds mainly the Norway spruce ( Picea abies ) and the Scots pine ( Pinus sylvestris ). To the east come the Siberian spruce ( Picea obovata ) (partially viewed as a subspecies of the common spruce), the Siberian larch ( Larix sibirica ) and the Dahurian larch ( Larix gmelinii ), the Siberian stone pine ( Pinus sibirica ) and the Siberian fir ( Abies sibirica ). As already mentioned, the species spectrum of trees in Eastern Siberia and North America is greater. There are around 20 common coniferous and hardwood tree species each, while there are only eleven in Western Siberia and only six in Northern Europe.

In North America, white spruce ( Picea glauca ) and black spruce ( Picea mariana ), coastal pine ( Pinus contorta ), balsam fir ( Abies balsamea ) and East American larch ( Larix laricina ) are the most common conifers.

With increasing frequency from north to south, the coniferous forests are interspersed with small-leaved softwoods of the genera birch , poplar (aspen and balsam poplar), alder and willow at suitable locations . Connected (birch) deciduous forests can only be found in the regions of Northern Europe and Kamchatka, which are favored by the maritime climate . However, they are mostly attributed to the forest tundra. Large stands of hardwood within the taiga line the large rivers of Siberia as softwood alluvial forests .

The symbiosis between the trees and the enormous, subterranean fungal network ( mycorrhiza ) is of great importance for the boreal forests: The fungi supply the trees with nutrients that the trees could not make available from the raw humus. In return, the mushrooms get mainly carbohydrates from the trees.

In addition to the trees, the species of character of the taiga also include the dwarf shrubs of the genera bilberries ( bilberry , bogberry , lingonberry ), which occur almost everywhere . On damp locations often grows wild rosemary .

Other typical plants are forest-cow-wheat , Seven Star , Lonicera caerulea , Moosglöckchen , shoot Ender club moss , cloudberry , Swedish dogwood , various orchid species (like the trees of their nutrients from the symbiosis with soil fungi related), ferns and club mosses . There are also numerous mosses , all of which are acid indicators . They either occur due to the initial substrate of the soil, or the conifers create the conditions favorable for these plants by influencing the soil properties. In addition, the Nordic forests are rich in lichens that grow both on the ground and on the trees. The frequency and length of beard lichens is an indicator of the age and closeness to nature of a forest, as they grow very slowly and are sensitive to air pollutants.

fauna

In contrast to most of the other large vegetation zones, the fauna is almost identical at the level of genera and families in the Nearctic North America and the Holarctic Eurasia. The animal population is small both in terms of the number of species and individuals. The prevailing coniferous forests and moors offer little food, the sporadic deciduous forests and succession areas are somewhat cheaper. Due to the pronounced winters, all animals have developed corresponding adaptations: Many birds migrate south, mammals and insects hibernate or are active under the protective snow cover.

The marten family is particularly well represented among the mammals . While practically all mammals of the boreal coniferous forests also occur beyond this, some species of marten (especially sable , European mink and spruce marten ) inhabit the taiga almost exclusively. If you consider the wood bison separately from the prairie bison , this also applies to this stately cattle.

From the tundra to the boreal coniferous forests, the following mammals are common: wolverines , lemmings , reindeer and North American caribou. Moose , various deer , wolf , coyote , lynx , brown bear , black bear , fox , hare , otter and New World otter live from the forest tundra to more southerly forest areas . In the boreal and nemoral are forests spread beaver , skunk , flying squirrels , chipmunks and squirrels .

The rivers and lakes of the boreal coniferous forests are home to numerous species of fish, including many species of salmon. Reptiles and amphibians are largely absent, as is larger soil organisms - dead organic matter is usually decomposed by fungi.

More than 300 species of birds live in the boreal coniferous forests, including typical whooper swans and black grouse .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The individual types of vegetation, biomes and ecoregions, as well as their zonal equivalents, vegetation zones, zonobiomes and ecozones, are not congruent! Different authors, different parameters and fluid boundaries are the cause. The article Zonal Models of Biogeography provides further information . An animated map display illustrates the problem in the Geozone article .

- ↑ The percentages mentioned are (in part) averaged values from various publications. The deviations are unavoidable, since in reality there are no clear boundaries between neighboring landscape types, but only more or less wide transitional spaces.

- ↑ The choice of colors has been changed to make it easier to see on the original "Vegetation Zones" map.

- ↑ A forest is a plant formation that “is essentially made up of trees and covers such a large area that a characteristic forest climate can develop on it”.

- ↑ Information according to the reference soil classification of the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (abbreviation WRB)

Individual evidence

- ^ German Weather Service Hamburg: Global radiation world 1981–1990

- ↑ Wolfgang Pfeiffer: Etymological Dictionary of German. dtv, Munich 1985.

- ^ Anton Fischer: Forest vegetation science. Blackwell, Berlin et al. 1995, ISBN 3-8263-3061-7 .

- ↑ Uwe Treter: Boreal Waldländer (The Geographical Seminar). Westermann, Braunschweig, 1st edition 1994, p. 10.

- ↑ averaged value from extensive research and comparisons in relevant specialist literature → see the respective description / sources of the files listed below : Vegetationszonen.png , FAO-Ecozones.png , Zonobiome.png and Oekozonen.png . Compiled and determined in the course of creating the aforementioned maps for Wikipedia → see also: Tabular overview of various landscape zone models and their proportions (PDF; 114 kB)

- ↑ Average value from extensive research and comparisons in relevant specialist literature → see description of the file : Wildnisweltkarte.png . Compiled and determined in the course of creating the aforementioned map for Wikipedia → see also: Tabular overview of various figures on the wilderness project. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Wolfgang Tischler: Introduction to Ecology. Fischer, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-437-20195-6 , pp. 185-192.

- ^ Richard Pott: General Geobotany - Biogeosystems and Biodiversity. Springerverlag, Heidelberg 2005, ISBN 3-540-23058-0 , pp. 415-416.

- ↑ The vegetation zones of the earth. Alexander World Atlas, Klett, Stuttgart 1976.

- ↑ Burkhard Frenzel: The vegetation of northern Eurasia during the postglacial warm season. 1955, in Erdk. 9, pp. 40-53.

- ↑ TL Ahti, L. Hämet-Ahti, J. Jalas: Vegetation zones and their sections in northwestern Europe. Annales Botanici Fennici 5, 1968, pp. 169-211.

- ↑ "Global Ecological Zoning for the Global Forest Resources Assessment" ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2000, FAO , Rome 2001. Adaptation to the vegetation types of the wiki map Vegetationszonen.png and verification via Atlas of the biosphere, maps: "Average Annual Temperature" , as well as in the case of unclear data via zoomable imap with u. a. Temperature data on solargis.info

- ↑ Global Ecological Zoning for the global forest resources assessment. ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2000, FAO , Rome 2001, verified via FAO card “Total Annual Rainfall” via sageogeography.myschoolstuff.co.za ( memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ W. Zech, P. Schad, G. Hintermaier-Erhard: Soils of the world. 2nd Edition. Springer Spectrum, Heidelberg 2014. ISBN 978-3-642-36574-4 .

- ^ FAO world map: Dominant soils of the world. ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ISRIC - World Soil Information website, accessed May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Klaus Müller-Hohenstein: The geo-ecological zones of the earth. In: Geography and School. Issue 59, Bayreuth 1989.

- ^ A b Anton Fischer: Forest vegetation science. Blackwell, Berlin a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-8263-3061-7 , p. 82.

- ↑ Table: The subglobal biomes (based on Isakov Yu. A. / Panilov DV 1997) in the excerpt from the commentary volume Vegetationsgeographie. ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. "Swiss World Atlas" website. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Peter Burschel, Jürgen Huss: Ground plan of the silviculture. A guide for study and practice. Parey, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-8263-3045-5 , p. 4.

- ^ Peter Hirschberger: Forests in flames - causes and consequences of global forest fires. WWF Germany , Berlin 2012.

- ^ Anton Fischer: Forest vegetation science. Blackwell, Berlin a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-8263-3061-7 , p. 242.