Forest tundra

| Forest tundra | |

|

Forest tundra on the east coast of Labrador |

|

| Area share | approx. 3% of the land surface |

| Ecological condition | ~ 55% pristine wilderness <25% largely near-natural |

| Land use | nomadic (reindeer) grazing, stationary livestock farming, forestry, limits to arable farming |

| biodiversity | low (1,300 - 1,700 species per hectare) |

| Biomass | low (70 - 90 t / ha dry matter) |

| Representative large protected areas (only IUCN Ia, Ib, II , NP , WE and PP ) |

Andreafsky (CAN) 5,261 km² Sand Lakes (CAN) 8,310 km² |

|

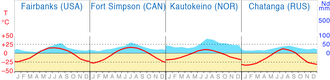

Climatic conditions

Forest tundra : climate diagrams |

|

| Exposure to sunlight | <800 - 1,100 kWh / m² / a (for the zone) |

| Ø temperatures |

Coldest month: −10 to below −30 ° C Annual mean: below −10 to 5 ° C Warmest month: above 0 to above 15 ° C |

| Annual precipitation | 200 - 800 mm (6 - 8 months of snow) |

| Water balance | humid |

| Growing season | 90 - 150 days |

Forest tundra (also Strauchtundra , Krummholzzone or Krüppelwald ) is the generic term for the transitional habitat from the treeless, subpolar tundra to the closed boreal coniferous forest (taiga). The forest tundra, like the taiga, occurs without exception in the northern hemisphere, as the southern hemisphere lacks the large land masses that enable the climate typical of boreal forests.

The term comes from geography and generally designates a certain type of landscape on the global scale . There are different definitions depending on the discipline, see section “Definition” .

Characteristic of the different forms of the forest tundra is a tree vegetation that becomes increasingly lighter towards the north and, on a moving relief, increasingly smaller and more scattered island-like forest areas in the tundra. The conifers or softwoods that can grow here (mostly) over permafrost soils show an increasingly poor growth towards the tundra.

definition

From the perspective of Geobotany (plant geography) forest tundra is a natural vegetation type , which especially in the transition from tundra to snow-forest climate is created. In their erdumspannenden ( geozonalen ) expansion, the tundra is among the vegetation zones . In addition, comparable plant formations occur worldwide in the subalpine altitude range of the mountains, which can be assigned to the forest tundra as non- zonal vegetation types . (However, their expansion is comparatively small, so that they cannot be shown on the world map.)

From an ecological point of view , the forest tundra is one of the largest possible (abstract) ecosystems that together form the biosphere . It itself is formed from typical biomes or ecoregions , which in turn are composed of the associated small-scale (specific) biotopes and ecotopes . These in turn subdivide the Earth-encompassing Boreal-Polar Zonoecoton or the Boreal Ecozone .

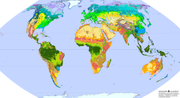

Spread and condition

The northern, subarctic vegetation zone of the forest tundra extends in its maximum extent from about 73 ° north latitude ( Chatanga estuary in northern Siberia) to 49 ° (200 km south of James Bay ). There are no sub-Antarctic forest tundras in the southern hemisphere . Instead, there are small areas of a Krummholz step in the southern Andes and the New Zealand Alps . The forest tundras merge towards the poles into the tundra zone and towards the equator into the boreal coniferous forest .

The non-zonal Krummholzzone occurs in most high mountains and forms the subalpine altitude here .

Establishing boundaries between types of vegetation is very difficult, especially with transition formations. Therefore, one often finds different classifications in the literature, which make up very large areas in the forest tundra. If, like Josef Schmithüsen or the FAO, the open lichen forests of Canada are included in the forest tundra, the zone here is up to 700 kilometers wide. If, according to Walter and Breckle, they are counted as part of the boreal forest belt, the breadth is only 10 to a maximum of 100 kilometers. There is also disagreement about the allocation of the deciduous birch forests of Northern Europe and Kamchatka. On the one hand they primarily form the tree line in these areas, on the other hand there are partly dense forests, to which the characteristics of the light, crippled forest tundra hardly apply.

By far the largest forest tundras stretch from northwest Canada down to Hudson Bay and on to the east coast of Labrador . The largest forest tundras in Europe are the mountain birch forests. They range from Finnmark to Lake Inari in Finland. The larch forest tundra of Siberia is best preserved in the Verkhoyansk Mountains .

In relation to the potential natural vegetation , around 3% of the earth's land surface are forest tundras today. In fact, around 55% of forest tundras are in a largely unaffected state at the beginning of the 3rd millennium. These areas are almost uninhabited wilderness . Less than 25% are still close to nature and have relatively little influence. However, these areas are mostly highly fragmented and are in a state of flux, due to being converted into usable areas or by overexploitation . In over 20% of the time, the original vegetation cover was greatly changed and shaped by anthropogenic landscapes . In these areas, near-natural forest tundra landscapes can only be found in small relics.

Characteristic

The forest tundra, like the tundra, is characterized by extreme climatic conditions. The permafrost soil thaws up to a maximum of half a meter deep in summer and offers the plants only little root space. The competition between the roots of the tree roots, which grow well beyond the crown area, leads to large gaps between the individual trees. In sparse forests, the ground thaws more easily, in the shade of dense wooded areas the ground remains frozen longer. The waterlogging over the frozen ground often creates swamps in summer. This interplay of frost and moisture is also the cause of the different types of bogs and soil structures such as the frequent pals . The herbaceous layer of the forest tundra essentially corresponds to the tundra , the shrub trees, however, form much more lush and taller forms here. There are also conifers such as spruce, pine or larch in central Alaska, Canada and northern Asia; as well as softwoods such as birch, willow or aspens in western Alaska, northern Europe or Kamchatka.

Trees at most four to six meters high usually grow in plains, their distance from one another to the north increasing and their appearance becoming more and more stunted. The spruce trees in particular are extremely narrow and branched to the ground. This prevents excessive snow loads in winter. On a more moving relief, the forest dissolves like a mosaic to the north: closed forest areas and open tundra alternate, with the forest growing in slightly warmer and more wind-protected areas (e.g. in river valleys and on southern slopes).

During the post-glacial warm period (Boreal from 7500 to 5500 BC) the tree line was further north. In some places - such as Canada - the current distribution of trees can be traced back to earlier, warmer periods. The trees on the northern tree line today only produce seeds in optimal years and the seedlings only survive if a few warm years follow. The supply by the wind from southerly growing, more regularly fruiting trees is important for the stand. In order to adapt to the colder climate, some trees - including conifers, which have little tendency in closed forest areas - are able to reproduce vegetatively without seed formation . A new tree is created when a branch of a "mother tree" hanging to the ground is covered with humus. This form of reproduction "in the same place", as well as the frequently observed seed germination on rotting trunks ( deadwood regeneration ), leads to a landscape that has hardly changed over centuries .

Climatic conditions

The earth's forest tundras lie in the north of the cold-temperate climate zone and are therefore usually characterized by cold climates with long, cold winters and short, cool summers. In the coldest month, the average temperatures drop to -10 to below -30 ° C, with the minimum at Verkhoyansk in Eastern Siberia being down to -70 ° C (this shows that the cold alone is not a limiting factor for the growth of trees) . There is snow for six to eight months. The warmest month is on average between 0 and 15 ° C; however, it can get much warmer in the continental areas. The long-term average temperature is below –10 to 5 ° C on average. For the polar forest tundra, there is also a very low level of solar radiation , which makes it difficult for plant growth , which is, however, caused by the midnight sun in high summer . T. is compensated.

With an average of 200 to 800 mm, the total annual rainfall is medium to low. However, the vast majority of areas are in distinctly continental, dry climates with less than 300 mm of annual precipitation. The long frost period and the low temperatures lead to a low evaporation rate , so that the water balance on the ground is humid despite the low amounts of precipitation .

The growing season is relatively short at 90–150 days.

According to the effective climate classification by Köppen / Geiger, the conditions mentioned above are referred to as the so-called snow-forest climate (abbreviation: D).

Further characteristics

In the continental Siberian forest tundra, mineral permafrost soils predominate, which are called cryosols according to the international soil classification system World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) . In places they are interrupted by soils of bog turf, which (like all organic soils with or without permafrost) belong to the histosols . Thus we find similar soils here as in the tundra. In other parts of the world, the forest tundras have very different soils (roughly in the order of their spatial extent): in the oceanic climate of northern Europe and North America, podsols , i.e. acidic, nutrient-poor soils, spread across large areas with histosols south of Hudson Bay to the northwest territories moderately developed cambisols and in the groundwater-affected areas of Alaska Gleysols .

The soil litter is moderate and decomposition is very slow.

Due to the abiotic factors mentioned above , the amount of biomass available is low (70–90 t / ha dry matter). Three to five tons are created every year.

Due to the already described, severely restricted ability of trees to reproduce ( characteristic ) , browsing by reindeer and elk as well as bush fires have a major influence on the formation of the forest tundra. Damage from large-scale insect infestation (e.g. moth in Scandinavia) can also be extreme . In connection with a mostly great lack of nutrients, forest tundras regenerate only very slowly or not at all.

Most of the Waldtundren stands on permafrost - also known as permafrost - which can be up to several hundred meters deep frozen. The precipitation-intensive zones on the western edge of Eurasia, where thick blankets of snow prevent the soil from cooling down to great depths, are free of permafrost. The permafrost only thaws on the surface in early summer (down to depths of 0.5 to 1 meter) and tends to become swampy due to the water. The root mass of the trees is therefore hardly anchored deeper than 20-30 cm in the ground. The swamping causes incomplete decomposition of the organic matter as well as insufficient mineralization of the nutrients bound in it due to the lack of oxygen . This is how bogs are formed in many places . The thick humus layer protects the permafrost subsoil from summer sunshine. If this litter layer is destroyed by fire, swamp-like lakes of 10–50 hectares may form, on which trees can initially no longer gain a foothold. This is why other forms of vegetation can be found here ( succession ).

flora

Mainly spruce , larch and birch grow in the forest tundra . In the maritime climate it is the birch trees, in the continental climate the conifers that form the northern tree line .

In northern Scandinavia, to Iceland and Greenland the tundra of which is Fjällbirke ( Betula pubescens subsp. Tortuosa ) formed in the north of Eastern Europe from the Siberian spruce ( Picea obovata ), further east follow the Siberian larch ( Larix sibirica ) and Dahurian larch ( Larix gmelinii ). On the Pacific coast of Russia there is primarily a birch, Erman's birch ( Betula ermanii ), which forms the tree line; there is also a crippled jaw. In North America, black spruce ( Picea mariana ) and white spruce ( Picea glauca ) grow in the forest tundra , as well as paper birch ( Betula papyrifera ) and balsam poplar ( Populus balsamifera ). In the more continental areas, the American larch (Larix laricina) is added.

The undergrowth of the forest consists mainly of dwarf shrubs such as various willows ( Salix ), blueberries ( Vaccinium ), moss heaths ( Phyllodoce ), Silberwurzen ( Dryas ), Alpine bearberry ( Arctostaphylos alpinus ) and dwarf birch ( Betula nana ). Mosses and lichens are also important in the undergrowth .

fauna

There are no mammals whose habitat is exclusively in the forest tundra. From the tundras to the forest tundras are common: arctic hare and mountain hare . From the tundra to the boreal coniferous forests, the following mammals are common: wolverines , lemmings , reindeer and North American caribou. Moose , wolf , coyote , lynx , brown bear , fox , rabbit , marten , otter and New World otter live from the forest tundra to the more southern forest areas .

Typical tundra and forest tundra birds: ducks , hawks , geese , mergansers , plovers , common raven , cranes , Arctic tern , gulls and skuas , rough-legged buzzard , snow bunting , snowy owl , ptarmigan , Lapland Bunting , Golden Eagle , Ruddy Turnstone , beach runners , divers kinds.

Indigenous people

Indigenous peoples still live in the almost deserted forest tundras , whose lives have always been shaped by the peculiarities of their land and who are still dependent on the largely intact ecological conditions of their ancestral home. The following selection therefore only takes into account those peoples in which at least some parts of the population have not yet fully adopted modern Western culture , whose economic practices are predominantly extensive and traditionally sustainable , and whose cultural identity still has a great - often spiritually anchored - bond with contains their natural habitat.

However, this should not hide the fact that the original "natural" way of life of all these people has already changed significantly due to increasing mechanization, changed dependencies due to the influence of the western lifestyle or different types of assimilation policies and declining traditional knowledge! There are many hopeful approaches to preserving or reviving the traditions. However, this mostly relates to language, material culture, customs or religion. Only in a few cases do these endeavors have a cultural-ecological background in order to promote the preservation of traditional farming methods in the forest tundra.

The main ethnic groups of the Eurasian Waldtundren are (from west to east) the Sámi the Fennoscandian mountains -type regions, the Nenets , Dolgan , Evenki , Evens , Koryak and Itelmen . Among the ethnic groups mentioned, the Dolgans are the only people that predominantly settle in the forest tundra. All were once mostly reindeer - nomads . Even today, reindeer herding plays a more or less important role for most of the peoples mentioned. They are sometimes called in ethnology cultural complexes collectively, "Siberia" and "paleo-Siberia".

The native inhabitants of the great forest tundras of North America - who still live to a greater or lesser extent from hunting and fishing - are the Yupik of Southwest Alaskas, who spoke or still speak Eskimo-Aleut languages . Of the Athabaskan Indians , the Kutchin , Hare-Slavey , Dogrib and Chipewyan in particular inhabit the open lichen forests. South and east of Hudson Bay there are some groups of the Swampy, Moose and James Bay Cree that live in the forest tundra. In Labrador, the small Naskapi people settle in the transition zone to the tundra. Some Innu roam the forest tundra on their hunting expeditions. These peoples belong partly to the North American cultural area "Arctic" and partly to the "Subarctic".

Use, development, endangerment and nature conservation

The forest tundra lies in the border area of arable farming. Sustainable forest management is not possible due to the very poor growth conditions for trees. At present, overexploitation of trees and shrubs occurs only occasionally in the vicinity of large settlements. As with the tundra, large-scale use has always been limited to reindeer grazing; the animals visit these areas in the transition seasons. It used to take place exclusively nomadically. Sometimes semi-nomadic and using modern methods. In addition, stationary livestock farming occurs in some areas. Fur hunting has a certain economic importance for the people of the forest tundra.

Above all under the soils of the forest tundras of Russia and Western Siberia, there are mineral resources, the extraction of which, apart from oil and natural gas, can be described as "selective" given the enormous size of the areas. The gas and oil production - z. B. in Northern Siberia ( Urengoy gas field ) - on the other hand, is associated with large-scale disturbances and far-reaching risks for the sensitive ecosystems. Soils and vegetation are so sensitive that even seemingly minor wounds from the climatic conditions become increasingly pronounced over time (so-called thermokarst ).

Global air pollution has acidified the waterways in some forest tundra areas and damaged the fragile lichens that are an essential food source for many animals. The man-made thinning of the ozone layer leads to increased ultraviolet radiation , which in turn can lead to direct damage to plants and animals.

The greatest threat to the forest tundra results from global warming , which is well above average in the high latitudes of the north. Dry periods will increase the risk of bush fires and infestation with insect pests. Due to the low regeneration capacity of the trees in these high latitudes, this will in part lead to a decline in forest cover. This can lead to a reduced food supply for various animals. In principle, however, the forest will expand further north. This will be more of a forest densification emanating from the taiga than an expansion of the trees into the tundra, since the predominantly vegetative reproduction and the poor pollination conditions are not improved by the increasing warmth. Instead, the first layer of shrubbery will be strengthened significantly and spread to the north.

The species diversity (and the additional biodiversity ) of the forest tundra is low (1,300 - 1,700 species per hectare).

According to the IUCN , around 16% of the total area was under protection in 2003. Around 70% of this is in North America and around 30% in Eurasia.

The exemplary large protected areas named in the info box each contain the largest possible proportion of the forest tundra vegetation type. In addition, these are exclusively areas in which the preservation (or restoration) of a natural state that is as unaffected as possible is a priority and which can be viewed as strictly protected in an international comparison.

Breakdown

The global vegetation type forest tundra must be seen as a generic term for a large number of smaller plant formations , biomes and ecoregions , which can be further subdivided down to the level of the biotopes in a different number of stages:

Further classification according to plant formations

According to similar appearances - and therefore essentially without considering the specific species inventory - the forest tundras can be further subdivided as follows (Nota bene: This breakdown is based on the names of Josef Schmithüsen ):

-

Softwood forest tundra - with a pronounced continental climate (less than 300 mm annual precipitation, less than −3 ° C annual mean temperature)

- Open deciduous coniferous trees - Siberian larch forest tundra

- Coniferous bush formations - stunted forest of the tree line in the far east of Siberia

- Boreal and subpolar open coniferous trees - open lichen forests and forest tundra of North America, as well as small areas west of the Urals

-

Hardwood forest tundra - in a maritime climate and moderate continental climate (over 300 mm annual precipitation, over −3 ° C annual mean temperature)

- Subpolar meadows and deciduous shrubs - cripple trees in the Aleutian Islands, Southwest Alaskas, Greenland and Iceland; as well as the stone birch forests of Kamchatka

- Subpolar deciduous deciduous forest - mountain birch forest tundra of Fennos Scandinavia

Classification

According to biomes / ecoregions

The further subdivision leads from the global view to the regional scale level . At this level, the entire ecosystem is primarily considered and not just the vegetation. One speaks of the biomes or ecoregions .

According to WWF ecoregions

The environmental foundation WWF USA has carried out an exemplary global classification according to ecoregions. The delimitation of these regions is based on a combination of different biogeographical concepts. They are particularly well suited for the purposes and goals of nature conservation .

The term forest tundra is not used in the WWF categories. In a total of 31 ecoregions, forest tundras, along with other types of vegetation, are part of the natural features. Of these, 14 ecoregions are included in the main biome ("major habitat type") tundra and 17 in the main biome boreal coniferous forest .

literature

- Georg Grabherr : Color Atlas of Earth's Ecosystems . Ulmer, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8001-3489-6

- Richard Pott : General Geobotany . Berlin / Heidelberg 2005, ISBN 3-540-23058-0 , pp. 353-398

- Jürgen Schultz: Handbook of the eco-zones. Ulmer-Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 201-204. ISBN 3-8252-8200-7 ( UTB ; Vol. 8200).

-

Heinrich Walter , Siegmar Breckle: Ecology of the earth. Spectrum Academic Publishing House, Heidelberg 1999.

- Vol. 3. Special ecology of the temperate and arctic zones of Euro-North Asia . Pp. 485-490. ISBN 3-8252-8022-5 .

- Vol. 4. Temperate and Arctic Zones outside Euro-North Asia . P. 482. ISBN 3-437-20371-1 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The individual types of vegetation, biomes and ecoregions, as well as their zonal equivalents, vegetation zones, zonobiomes and ecozones, are not congruent! Different authors, different parameters and fluid boundaries are the cause. The article Zonal Models of Biogeography provides further information . An animated map display illustrates the problem in the Geozone article .

- ↑ The percentages mentioned are (in part) averaged values from various publications. The deviations are unavoidable, since in reality there are no clear boundaries between neighboring landscape types, but only more or less wide transitional spaces.

- ↑ Information according to the reference soil classification of the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (abbreviation WRB)

- ↑ The WWF ecoregions can extend into neighboring vegetation zones due to the perspective - taking into account the potentially occurring plant and animal species. The pure consideration of the plant formations is therefore not used here!

Individual evidence

- ↑ Global radiation world 1981–1990 . German Weather Service Hamburg

- ^ Anton Fischer: Forest vegetation science. Blackwell, Berlin et al. 1995, ISBN 3-8263-3061-7 .

- ↑ For the mean value from extensive research and comparisons in relevant specialist literature, see the respective description / sources of the files listed below : Vegetationszonen.png , FAO-Ecozones.png , Zonobiome.png and Oekozonen.png . Compiled and determined in the course of creating the aforementioned maps for Wikipedia, see also: Tabular overview of various landscape zone models and their proportions (PDF; 114 kB)

- ↑ For the mean value from extensive research and comparisons in relevant specialist literature, see description of the file : Wildnisweltkarte.png . Compiled and determined in the course of the creation of the aforementioned map for Wikipedia, see also: Tabular overview of various figures on the wilderness project ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Global Ecological Zoning for the global forest resources assessment . ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) 2000, FAO , Rome 2001. Adaptation to the vegetation types of the wiki map Vegetationszonen.png and verification via Atlas of the biosphere, maps: “Average Annual Temperature” ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2015 in the web archive archive.today ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , and if the data is unclear about zoomable imap with u. a. Temperature data on solargis.info

- ↑ "Global Ecological Zoning for the Global Forest Resources Assessment" ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2000, FAO , Rome 2001, verified via FAO card “Total Annual Rainfall” via sageogeography.myschoolstuff.co.za ( memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ W. Zech, P. Schad, G. Hintermaier-Erhard: Soils of the world. 2nd Edition. Springer Spectrum, Heidelberg 2014. ISBN 978-3-642-36574-4 .

- ^ FAO world map: Dominant soils of the world . ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ISRIC - World Soil Information. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Müller-Hohenstein: The geo-ecological zones of the earth. In: Geographie und Schule , No. 59, Bayreuth 1989

- ↑ Table: The subglobal biomes (based on Yu. A. Isakov, DV Panilov, 1997) in the excerpt from the commentary on “Vegetation Geography ”. ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 451 kB). "Swiss World Atlas". Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Göran Burenhult (according to ed.): Primitive peoples today. Vol. 5 from “Illustrated History of Mankind” Weltbild-Verlag, Augsburg, 2000.

- ↑ Atlas of the Peoples. National Geographic Germany, Hamburg 2002.

- ^ Society for Threatened Peoples . Various articles on the current situation of the indigenous peoples.

- ↑ USGS World Energy Assessment Team . (PDF) US Geological Survey. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ S. Chape (Ed.), M. Spalding (Ed.), MD Jenkins (Ed.): The World's Protected Areas: Status, Values and Prospects in the 21st Century. University of California Press, 1st Edition, Berkeley 2008, ISBN 0-520-24660-8 .

- ↑ J. Schmithüsen (Ed.) Atlas of Biogeography . Meyer's large physical world atlas, vol. 3. Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim / Vienna / Zurich 1976, ISBN 3-411-00303-0