American bison

| American bison | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American prairie bison ( Bos bison bison ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Bos bison | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The American Bison ( Bos bison , sometimes Bison bison ), often called buffalo (Engl. Buffalo called), is one in North America common wild cattle and the largest land mammal in the region. Whether he wrote with in Europe occurring him like bison own genre of bison ( Bison forms) is controversial in research. Today, however, both are often placed with the actual cattle ( Bos ).

The habitat of the prairie bison ( B. bison bison ) is in the open grasslands of the North American prairies , that of the wood bison ( B. bison athabascae ) in northern forest areas. Their diet consists almost exclusively of sweet grasses and sour grass plants , which the ruminants ingest when grazing slowly.

Bison cows and calves live in herds that usually number around fifty animals. The bulls either live as solitary animals or in their own small groups. During the rut between July and August, the bulls join the cows and hold tight to their side ( tending ) before they mate. In April and May the cows give birth to their calves, which are suckled by the mother up to an age of 4 to 6 months.

While the bison population is estimated to be around 30 million animals prior to the arrival of European settlers in North America, it fell dramatically by the end of the 19th century due to excessive hunting. Thanks to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 and Wood Buffalo National Park in 1922, the bison were given sanctuaries in good time. Today the total number of wild animals is estimated at more than 30,000 individuals. The species is classified as "potentially endangered" due to its dependence on protective measures and the only small number of individual populations .

In May 2016, President Barack Obama signed the National Bison Legacy Act , which makes the American bison the national animal of the United States of America alongside the bald eagle .

features

The bison is the largest land mammal in America . Its thick fur is dark brown, almost black in winter. The head, forelegs, humpbacks and shoulders are covered with longer hair, while the fur on the flanks and buttocks is much shorter. With increasing age, the hair on the hump and shoulders begins to lighten, and this lighter coat color is particularly pronounced in older bulls . At the beginning of spring, the change to summer fur sets in, whereby clumps of older fur - especially on the animals' shoulders - can persist into August. When they are born, calves have a light reddish coat that turns brownish-black within their first three months of life. After five to six months, the coat color of the young animals resembles that of their parents.

Bison have a sex dimorphism . Sexually mature bulls, weighing up to 900 kilograms, are significantly heavier and larger than adult cows, which weigh between 318 and 545 kilograms and are only about half as heavy. Calves weigh between 14 and 32 kilograms when they are born, while one-year-old bison of both sexes can weigh between 225 and 315 kilograms. The shoulder height of male bison is between 1.67 and 1.86 meters, while that of females is between 1.52 and 1.57 meters. Compared to female bison, males have stronger, more evenly curved horns and often jagged horns at the base of their heads. In addition, the dark fur on males is longer on the forehead, neck and front legs. The head of male animals appears wider and more massive than that of female specimens.

Wood bison ( B. bison athabascae ) and prairie bison ( B. bison bison ) are largely similar in their physical characteristics. Hal Reynolds, Cormack Gates and Randal Glaholt list a total of six distinguishing features between the two subspecies:

- In forest bison, the hair on the head, around the horns, in the stomach area and that of the throat beard is significantly shorter and less dense than in prairie bison.

- The two front legs of prairie bisons have an apron-like tuft of hair in the upper area, which in the wood bison is either only slightly developed or completely absent.

- In prairie bison, the fur on the shoulders and neck area is lighter in color than in the forest bison.

- The tail of the wood bison is usually longer and more hairy than that of the prairie bison.

- The tuft of hair at the opening of the foreskin is usually shorter and thinner in the wood bison than in the prairie bison.

- The highest point of the hump is further forward in the wood bison than in the prairie bison. It is still in front of the front legs, while in the prairie bones it lies over the front legs.

Distribution, habitat and migration

Historical distribution

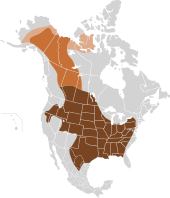

Today's research assumes that bison came to North America in two waves over a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska , the Beringia , in the mid- Pleistocene and then again in the late Pleistocene . B. ( bison ) occidentalis appeared about 10,000 years ago , from which today's subspecies B. bison bison and B. bison athabascae developed around 5,000 years ago . The latter adapted to the forest areas in the northern range, while the subspecies B. bison bison populated the open grasslands in the central and southern part of North America. The disappearance of the bison in the extreme north of the historical range is now attributed to a combination of changes in the habitat and hunting by humans.

In pre-European times bison lived mainly in the prairie areas, but they were also found on the Great Lakes and as far as the Atlantic Ocean - there between New England and Florida . They also lived in western Saskatchewan and central Alberta as well as in the southwest of Manitoba in the north and as far as the Gulf of Mexico and as far as Mexico in the south. They were also found in eastern Oregon and northern California .

Written sources from the late 18th and early 19th centuries show the existence of wood bison populations in the southern Yukon , the western Northwest Territories , Alberta and British Columbia , while bison in Alaska and the western Yukon were believed to have disappeared by then . The range of the prairie bison originally comprised an area that stretched from Mexico to the Great Slave Lake and from Washington to the Rocky Mountains . Intensive hunting - especially in the second half of the 19th century - then led to the almost complete extermination of the bison in its historical range, so that towards the end of the 19th century only vanishingly small residual populations remained.

Today's distribution and habitat

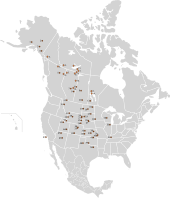

Today's distribution of wild bison is limited to a number of independent sub-populations in the United States and Canada. They initially emerged from the efforts of private individuals to preserve the species, later through state protective measures. 87% of the total of 62 herds of wild prairie bonsons are located within the historical range, while eight herds native to California , northern British Columbia and Alaska are located outside the original range. Nine out of a total of eleven herds of wild bison are now within their historical range.

While the historical distribution area of the prairie bison comprised a total of 18 different habitat types, the subspecies is now present in 14 of these habitat types. Of the original seven habitat types of the forest bison, at least one herd is still settled in four today. Our knowledge of the natural habitat selection of bison is made more difficult by the fact that the herds occurring today are artificially kept in protected areas. The selection of the habitat is presumably primarily related to the amount and type of food available, although factors such as the depth of snow in winter can also play a role. In general, prairie bison prefer open grassland, while wood bison can be found in wooded areas.

Hike

Not all bison migrate. Long hikes were only necessary in dry regions of the prairie in order to develop new grazing grounds and water points. For this purpose, the individual herds joined together outside the mating season to form large migrating herds that could consist of thousands of animals. The herds of bison migrated for several hundred kilometers before they broke up again to move on in the original smaller herds. Today there are only a few such migrations left. Only in Alberta there is a large bison migration over 250 kilometers twice a year.

Way of life

Food and subsistence

American bison feed almost exclusively on grasses . A study of prairie bison excretions in northern Oklahoma in 1994 and 1995 found that at least 98% of the diet consisted of grasses throughout the year, while the animals largely spurned herbaceous plants. Among the grasses, the sour grass family accounted for 17–44% in winter and spring, while their share of the bison diet fell to 11–16% in summer and autumn. Among the sweet grasses , the genera Andropogon , Paspalum , Sorghastrum , Sorghum and Schizachyrium made up the largest share with 44–64%.

When eating, the bison move slowly over the grassland in small steps. As ruminants , they have a multi-part ruminant stomach which, through microbial digestion, enables them to use as food those plant components that are indigestible to other mammals (especially cellulose ). To ruminate, bisons take regular breaks in which they chew up the initially roughly chewed plant material and chew it again before the food, which has been further chewed in this way, is fed to the actual digestion. In winter, the bison use their heads to uncover the grasses hidden under the blanket of snow, so that they can also eat enough food in winter.

A study published in 2008 suggests that bison may play a large role in the distribution of plant seeds in their habitat. Hair and faeces samples showed that bison ingested more than 76 different types of seed and distributed them in the grassy landscape.

Social behavior

Bison cows, calves and not yet sexually mature bulls live in herds, while sexually mature bulls can be found either as solitary animals or in small groups of their own. The herd size of prairie bison is usually larger than that of wood bison. Also, the herd of wood bison decreases during the rut, while it increases in prairie bison. In the high grass plains of Oklahoma , herds of more than 1,000 animals were observed at the beginning of the 21st century. Studies of the herd size in Yellowstone National Park have shown that a third of the animals live together in groups of fewer than 10 individuals in winter, while around half of the animals group together in herds of more than 95 individuals in summer.

Agonistic behavior occurs in both sexes and regardless of the age of the animals or the season. Most often, however, it can be seen during the rut when the bulls join the herd. Aggressive behavior towards conspecifics is usually initiated by showing off, in which one or both animals present their flank - presumably in order to intimidate their counterpart by their body size. Your state of excitement is also signaled by raising your tail and lowering and swinging your head. If the excitement continues to grow, the animals scratch with their front hooves with their heads still lowered. In most cases, this impressive behavior is sufficient and one of the animals withdraws without a fight. If a fight does nevertheless occur, the opponents stand face to face, hit their heads together and try to hit their opponent in the flank with their horn tips. Occasionally they hook the horns together, but the argument ends as soon as one of the cops signals submission through his behavior.

Reproduction

Sexual maturity and fertility

American bison are polygynous : one bull covers several cows. Bison cows usually give birth to their first calf when they are three years old. Males reach sexual maturity at three years of age, but are not fully grown until they are six years old. In fights against older bulls, younger bison bulls up to this age can rarely prevail, which is why they are usually excluded from reproduction.

Rut and mating

The rutting season of the American bison takes place between mid-July and late August. During this period of time, the bulls accompany the cows and stand closely by their side ( tending ). As soon as a bison cow tries to move away from the bull accompanying her, the bull stops her by swinging his head. This behavior can last anywhere from a few minutes to several days. It ends as soon as the bull turns away from the cow, or when he is ousted by a stronger conspecific. During the rutting season, the bull bison fights for dominance, which sometimes result in injuries or the death of an opponent. As the two biologists Christine Maher and John Byers were able to show in 1987, bull bison take increasingly higher risks in these fights as they get older, presumably because they have less to lose.

During the rut, bull bison urinate in sand pits and on their legs, chest hair and throat beard. They roll around in the urine-soaked sand, especially before their dominance fights with other bulls. The scent absorbed in the process probably serves to intimidate rivals and to stimulate nearby cows to mate.

By sniffing the cows' external genitals, the bulls determine whether a cow is ready to mate. During this so-called flehmen , the bull lifts his head, stretches his neck and pulls his lips apart. If the concentration of sex hormones in the cows' urine is high enough and the cow is ready to mate, the bull mounts it. After mating, the cow usually urinates and holds its tail up until it slowly lowers it over the course of four to eight hours.

Gestation time, birth and suckling time

After nine months of gestation, a bison cow gives birth to a 15-25 kg calf between mid-April and the end of May. This can stand on its own two feet after around 7 to 8 minutes and move with the herd after one to two days. An intense mother-child relationship develops between the calf and its mother. The calf is suckled by the mother up to an age of 4 to 6 months. The mother animal guards the calf and fiercely defends it against all enemies. Bull bison do not take part in the rearing of the calves.

Predators, diseases and causes of mortality

Predators

Because of their size, bison have few serious predators. Wolves ( Canis lupus ) share a fate similar to bison with their decline in populations caused by intensive hunting and can only be found with them today in a few areas of North America such as Wood Buffalo National Park and Yellowstone National Park. Investigations after the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone in the mid-1990s have shown that wolf packs killed bison after less than 25 months - and not after several years, as the researchers originally suspected - whereby they mainly focused on calves as well as on older and weak animals. Compared to attacks on Rocky Mountain Elk ( Cervus canadensis nelsoni ), one of the wolves' main prey, those on bison were less successful. In more than two-thirds of the observed cases, the bison showed no escape reaction and went over to the defense, whereby the wolves usually gave up the attack.

Attacks by grizzly bears ( Ursus arctos horribilis ) on adult bison are extremely rare. Both an evaluation of historical reports by Frank Gilbert Roe and more recent studies by Travis Wyman have shown that the earlier view that grizzly bears pose a greater threat to bison than wolves is not correct.

Diseases and parasites

The American Bison Specialist Group (ABSG) listed nine diseases in the context of conservation of bison relevant: anaplasmosis of ruminants , anthrax , bluetongue , bovine spongiform encephalopathy , bovine brucellosis , tuberculosis in cattle , bovine virus diarrhea , paratuberculosis and Malignant catarrhal fever . Among them, bison-related bovine brucellosis has received increased public attention in recent decades. In female animals, the disease can lead, among other things, to miscarriages , inflammation of the uterus and incomplete afterbirth . The disease, presumably introduced by cattle from Europe to North America, occurs in around 24% of the total population of prairie bonsons in North America (as of 2010). For fear of being transmitted to cattle, bison from Yellowstone National Park have been allowed to be killed outside the park since the turn of the millennium if the population exceeds 3,000 without having been tested for bovine brucellosis. Nature and animal protection organizations have been fighting this for years. They claim that so far there has been no confirmed case of the transmission of the brucellosis bacteria to cattle. A group of researchers led by Julie Fuller estimated in 2007 that eradicating brucellosis in Yellowstone National Park would increase the population by 29%.

A total of 31 types of endoparasites that bison use as host animals are known. Most of these occur in animals that are kept in captivity. Free-living bison are attacked by roundworms of the genus Dictyocaulus and tapeworms of the genus Moniezia . A study carried out on bison in Yellowstone National Park showed that it is mainly older animals that are attacked by roundworms and not - as is common in livestock - calves.

Ectoparasites such as mosquitoes of the genus Aedes , black flies of the genus Simulium , horseflies (Tabanidae), snipe flies (Rhagionidae) and real flies (Muscidae) infest bison especially in the warm summer months, when the bison fur is short and thus most permeable to insect bites. A study published in 2015 on the interaction between bison and midges of the genus Culicoides came to the conclusion that mud pits used by bison probably play an important role in the mosquito population dynamics.

Causes of mortality

The hunting by humans today represents one of the most significant mortality represents causes. Second ranked wolves ( Canis lupus ), kill the weakened or especially in winter elderly individuals. Particularly harsh winters with increased climatic stress and reduced food supply also cause a higher mortality rate among wild bison. In addition, bison are affected by the occasional occurrence of anthrax . Miscarriages caused by bovine brucellosis increase the death rate of calves and cows. In Yellowstone National Park, animals also die in hot springs and from tourist accidents every year.

Bison typically have a life expectancy of twenty years. A maximum age of forty can be reached in zoos , which is very unlikely in the wild.

Research history and systematics

|

Internal systematics of the actual cattle according to Hassanin et al. 2004

|

First described the American Bison was by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 published the tenth edition of his work Systema Naturae . Linné put the American bison together with domestic cattle in the genus of actual cattle ( Bos ). Due to morphological peculiarities, C. Hamilton Smith established a separate subgenus "bison" for the American bison and its European counterpart, the wisent ( Bos bonasus ) in 1827 . In 1849 Charles Knight raised the sub-genus created by Smith to the rank of a genre of its own. Since then, the exact position of the American bison has been the subject of ongoing scientific discussion, which has led to different works classifying the bison either in the genus Bos or in the genus Bison . The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, for example, uses the American bison in its Mammal Species of the World series under the generic term bison , while the Museum of Texas Tech University uses the generic term Bos in its Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico . The inclusion in the genus Bos is supported by molecular genetic studies from 2004. They showed that the American bison and wisent are not related to one another. The former is more closely related to the yak ( Bos mutus ), while the latter is the sister species of the aurochs ( Bos primigenius or the domestic cattle Bos taurus ), which makes the genus bison paraphyletic . Later genetic analyzes could confirm this, so that most of the more recent classifications lead the American bison (and the wisent) within the actual cattle. Including fossil forms, the steppe bison ( Bos priscus ) is the closest relative of the American bison according to genetic analyzes.

|

Closer relationship of the American bison including fossil representatives according to Palacio et al. 2017

|

The widely used division into the two subspecies prairie bison ( B. bison bison ) and wood bison ( B. bison athabascae ) is also the subject of scientific debate. Due to differences in the skeletal structure and external characteristics - such as body size and the texture of the fur - Samuel Rhoads established the subspecies of the wood bison in 1897. This division into two subspecies was criticized in a publication from 1991 by Valerius Geist as inadmissible; instead, he sees them as ecotypes . Geist argues that the morphological differences put forward by Rhoads were insufficient to warrant a subspecies B. bison athabascae . The settlement of prairie bison not far from the Wood Buffalo National Park in the years 1925–1928 and the resulting hybridization of the wood bison with the prairie bison made the distinction even more difficult. Recent genetic studies sometimes come to contradicting results. In 1999, Gregory Wilson and Curtis Strobeck of the University of Alberta carried out DNA analyzes of animals from 11 different populations of wild bison and concluded that the differences between forest and prairie bones are greater than those between animals within both subspecies. In contrast, research by a research group led by Matthew Cronin from the University of Alaska Fairbanks in 2013 showed that the genetic diversity between domesticated cattle is greater than that between forest and prairie bison.

Tribal history

The origin of the American bison is not fully understood. The problem with the reconstruction of the phylogenetic past of the species is that the various fossil bison forms can usually only be distinguished on the skull, especially the horn position, regardless of any deviations in body size. Bison-like cattle first reached North America in the course of the Middle Pleistocene , coming over the Bering Bridge from Eurasia . There the genus Bos had already spread in the transition from the Old to the Middle Pleistocene, predecessor forms may be found in Leptobos or Pelorovis . In North America, Bos spread relatively quickly and competed there with early horses and mammoths in the open steppe landscapes . The immigration via the Bering Strait was not a one-off event, however, as genetic data indicate that at least two waves can be distinguished: the first around 195,000 to 135,000 years ago (corresponding to the penultimate glacial period) and a second around 41,000 to 25,000 years ago (corresponding to the last glacial period ). As a rule, two groups of bison-like cattle can be distinguished in North America. Bos latifrons was native to the more southerly regions from the 60th parallel north , a gigantic shape which, with an estimated body weight of around 2 tons, was twice the weight of today's American bison and whose horns were up to 2 meters apart. Bos latifrons is documented at numerous localities, for example in Snowmass in the US state of Colorado or in American Falls in Idaho . The far north, however, was inhabited by the steppe bison ( Bos priscus ), which was also very large, but had differently structured horns. Significant sites can be found here, including in the Old Crow Basin in the Canadian Yukon Territory , with Blue Babe , an excellently preserved ice mummy from Alaska has come down to us. It is sometimes assumed that in the course of the last glacial period, as a result of the successive reduction in body size, Bos latifron changed into Bos antiquus , which occurs, among other things, at the asphalt pits of Rancho La Brea in California . In contrast, the steppe bison developed into Bos ( bison ) occidentalis in the north.

Today's American bison can be detected for the first time after the last glacial period during the Holocene . The reasons for its formation can possibly be found in the disintegration of the open landscapes after the regression of the glacier masses and the expansion of wooded biotopes, which, similar to the predecessor forms of the European bison, the total populations of the bison were strongly split. As a result, there was a further reduction in body size and a reorientation of the horns. Sometimes these changes are explained by the increased hunting pressure from the Paleo-Indians . In the southern part of North America, the oldest remains of the American bison are between 8000 and 6500 years old. The period goes hand in hand with the spread of short-stemmed grasses ( C 4 plants ). In more northerly regions of North America, the American bison appeared around a thousand years later.

Existence and endangerment

In Yellowstone National Park live today from 2300 to 5000 bison what Yellowstone one of the areas with the highest population density makes in the United States.

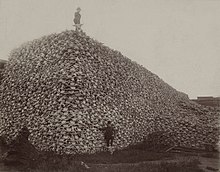

The size of the bison population before the arrival of European settlers has long been estimated at 60 million animals. Richard Irving Dodge (1827–1895), Colonel in the United States Army and author of books on the American West, estimated the size of a herd he observed in 1871 in a letter to the zoologist William Temple Hornaday (1854–1937) at 25 times 50 miles. Hornaday concluded that there were 4 million animals in the herd observed by Dodge. The Canadian naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) extrapolated this number to the total area of the area west of the Mississippi and came to the figure of 60 million animals, which is widespread in the literature. Based on a more recent estimate by Tom McHugh from 1972, this number has since been rejected as too large. McHugh assumes a capacity of 26 bison per square mile , resulting in an original total population of 30 million individuals. The American wildlife biologist Dale F. Lott largely follows McHugh in his book American Bison - A Natural History , published in 2002, but comes to the conclusion - especially considering weather-related population fluctuations - that the historical population can be around 3 to 6 million below that of McHugh indicated value.

Because of the heavy hunting, the population decreased to less than 1,000 animals by the late 19th century. As a result of the efforts to protect the animals that began in the 1870s, the population recovered, which led to a doubling of the number of prairie bisons between 1888 and 1902. In 1970 there were around 30,000 animals in North America, around half of them in private herds. The number of wild prairie bisons was estimated at more than 20,500 individuals in 2010, and that of animals kept in private herds at an additional 400,000. The total stock of wood bison fell to around 250 individuals by the end of the 19th century. As a result of the grandfathering measures imposed by the Canadian government, the population recovered to around 11,000 animals in 2008.

In a rash measure, between 1925 and 1928 more than 6000 prairie bones, some of whom were infected with anthrax and tuberculosis , were brought to the Wood Buffalo National Park, where they mixed with the last native wood bison. The subspecies of the wood bison was already thought to be extinct until 1957 in the remote northern part of the park a pure-blooded and uninfected herd of around 200 wood bison was discovered. Around two dozen of these animals were brought to the Elk Island National Park south of Lake Athabasca and to the specially created Mackenzie bison sanctuary north of the Great Slave Lake , where they have now multiplied to a total of over 2000 pure-blooded wood bison.

The IUCN now classifies the American bison as "potentially endangered" due to its dependence on protective measures and the low number of populations .

Humans and bison

Before the arrival of the European settlers

During the Ice Age , the ancestors of the bison migrated from Asia to America via the Bering Land Bridge . They moved through the ice-free corridor along the Rocky Mountains and later spread across the continent. There the herds grew to a number of several million animals.

After paleo-Indians moved along the west coast and then turned eastward, they also invaded the bison habitat. They encountered huge herds about 10,000 years ago at the latest, which were suitable to compensate for the disappearance of the megafauna and with it the oldest bison species. The resulting new way of life found its expression in the Folsom culture . At the Folsom site in New Mexico, bison hunting with a spear between the ribs of such an animal was possible as early as 8000 BC. Prove. The oldest Canadian site is located south of Taber near Chin Coulee in Alberta . It was dated 7000 BC. Dated.

The bison served the Paleo-Indians as food, its fur, sinews and bones for the production of clothing, blankets, shields, ropes, glue, pillow fillings, dishes, rattles, jewelry, tools and tipis and the buffalo dung as fuel. In the Plains, however, bison hunting with bows and arrows without horses (these were first introduced by the Spaniards, as well as saddles and bridles) was only possible to a limited extent. Therefore, the few Indians living there developed other methods to kill bison in large numbers.

One of these hunting methods was the "Buffalo Jump" (dt. "Buffalo Jump" ): A fast young man was selected and wrapped in a bison fur. On his head he wore a buffalo head with ears and horns. Disguised like that, he stalked a herd of buffalo grazing near a precipice. The remaining Indians circled the bison from the other side and initially remained hidden. At a signal they slowly walked towards the bison. As soon as the bison began to flee, the disguised Indian began to run too. He lured the bison to the abyss and let them fall over the cliff to their death.

From the 16th to the end of the 19th century

The Spaniard Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was the first European to describe the bison in his book The Shipwrecks of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca based on his observations in the 1530s. With the significant spread of feral horses towards the middle of the 17th century, bison hunt became much easier. Now the Indians could hunt the bison all over the prairie and created the new culture of the Plains Indians . More and more tribes penetrated these areas to feed on the meat of the animals. From the 18th century, they also advanced into the previously uninhabited dry steppe.

According to reconstructions, Indian and white hunters only killed as many bison as they needed for their own needs until 1870. In 1871, tanners in Great Britain and Germany developed a new process with which buffalo leather could be transformed into shoe soles and drive belts for machines. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, all European countries reequipped their armies, including boots for soldiers. Because of the associated profits, the bison hunters shot the animals en masse, only interested in the leather; they left the meat to rot on the prairies. The United States urgently needed foreign currency after its civil war , so the government let it go.

The development of the country with railway lines also played a role; During construction, large numbers of bison were shot down to feed the railroad workers. With the opening of the Central Pacific Railroad , bison were shot with rifles from the train. A single “buffalo hunter” could kill around 50 to 100 animals a day. One of the most famous bison hunters was William Frederick Cody , who was soon called Buffalo Bill. He is said to have shot up to 60 bison in one day with the rifle.

From 1872 to 1874, more than a million buffalo hides were shipped eastwards each year. The buffalo population was divided into a north and a south herd by the railway line. First the southern herd was exterminated, then the northern herd as well. Only the north-west with its defenders, the Lakota and Cheyenne , was initially able to keep even larger bison herds. In order to deprive the tribes of these Plains Indians of their livelihood and to force them into their reservations through hunger , the whites also decimated these bison herds. They killed the last 10,000 animals by setting up snipers at water holes.

Thanks to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the bison were given a refuge in time. As of January 15, 1883, most animals were banned from hunting in the park. However, poaching was a major problem even after the US Army at Fort Yellowstone took over the park in 1886. In 1894, around 800 specimens lived across North America, around 200 of them in Yellowstone as the last wild bison in the United States. Their number fell to only 23 animals by the low point in 1902. Their survival is thanks to the zoologist and conservationist George Bird Grinnell , who fought for the protection of the species since the 1890s and who, with the help of his personal friend, the later US President Theodore Roosevelt , organized pressure on the US Department of the Interior until the Army made the suppression of poaching in Yellowstone National Park a priority.

Todays situation

Bison meat has recently been enjoying increasing popularity again in America, also as an "organic alternative" to beef , and it is also becoming more popular in Europe. The low demands of the bison on their food base and good meat prices make bison ranches appear to be advantageous also from the aspect of climate protection . The largest buffalo breeder is retired media manager Ted Turner , who is also the second largest private land owner in the United States. He has been herding and marketing bison meat in his own chain of restaurants, Ted's Montana Grill , since the 1970s .

The US Department of the Interior is coordinating a program that allows several federal agencies such as the National Park Service , the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, together with the states of the prairie regions, various Indian peoples, and in coordination with Canadian authorities to reintroduce the population Want to promote bison in as many areas as possible: In an interim report from 2014, 17 areas under different management are named in which bison live freely or in spacious enclosures. A total of 25 areas are being examined for their suitability, with a focus on the risk of transmission of brucellosis, and specifications are made for the expansion of the population.

For cultural reasons, the state of Montana allows the Confederate tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederate Salish and Kootenai , the Nez Percé , the Shoshone-Bannock , the Confederate tribes of the Yakama - and the Blackfeet Nation to hunt bison again today and moose north of Yellowstone National Park in parts of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness . The tribes rely on historical contractual rights. The Absarokee are also trying to maintain this right. However, the official bodies do not consider an expansion to be necessary due to the threat to continued existence. Hunting is generally allowed in order to prevent the bison from spreading outside the national park. This in turn is justified with the risk that the animals could transmit brucellosis to cattle. However, so far there have only been transfers from elk to cattle.

In May 2016 signed by President Barack Obama to the National Bison Legacy Act , of the American Bison next to the bald eagle to national animal makes the United States of America.

One of the greatest initiatives for the social and economic development of the Great Plains is linked to the bison. The concept of Buffalo Commons is an attempt to turn the demographics and history of the Midwest back to the status quo of the time before the massive influx of white settlers: herds of buffalo are set to roam the vast plains by the hundreds of thousands. and become the basis for an economy based on sustainable agriculture and tourism. The reason is the foreseeable drying up of the aquifers, which are required for capital- and energy-intensive agriculture using irrigation farming.

Today bison are also kept outside North America for meat production. The bison is kept behind 1.60 m high fences, where the fence posts must be very stable so that they cannot be pushed over by a bull. To avoid the stress of being transported to the slaughterhouse, bison are usually killed in the pasture with a gunshot. When slaughtered in Germany, bull bison have a live weight of 515 kg, bison heifers (females) of 475 kg. The slaughter yield (usable meat) is 50.8% for bulls and 51.9% for heifers. In addition to direct meat sales, bison meat is also sold in canned meat in Germany and, after processing, as various types of sausage and smoked meat. The German Bison Breeding Association has existed since 2004 .

As the bison show in Safariland Stukenbrock in North Rhine-Westphalia shows, bisons can also be tamed and trained. According to a SAT-1 report, the trainer Marcel Krämer is one of three people in the world who have tried this successfully.

literature

- Valerius Geist : Buffalo Nation: History and Legend of the North American Bison . Voyageur Press 1996, ISBN 978-0-89658-313-9

- Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie Jr .: Family Bovidae (Hollow-horned Ruminants). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World Volume 2: Hooved Mammals Lynx Edicions, Barcelona (2011), ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4 , p. 444 -779 (pp. 557-579)

- Andrew C. Isenberg: The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920 , Cambridge, New York 2000

- Heidi, Hans-Jürgen Koch: Buffalo Ballad , Edition Lammerhuber 2004, ISBN 978-3-901753-73-2

- Dale F. Lott: American Bison - A Natural History , London 2002, ISBN 0-520-23338-7

- Jerry N. McDonald: North American bison: their classification and evolution , Berkeley, Los Angeles 1981

- Tom McHugh: The Time of the Buffalo , New York 1972

- Margaret Mary Meagher: The Bison of Yellowstone National Park , Washington DC 1973

- Hal W. Reynolds, C. Cormack Gates, Randal D. Glaholt: Bison (Bison bison) , in: George A. Feldhamer, Bruce C. Thompson, Joseph A. Chapman (Eds.): Wild Mammals of North America. Biology, Management and Conservation , 2nd Edition, Baltimore, London 2003, pp. 1009-1060

- Frank Gilbert Roe: The North American Buffalo. A Critical Study of the Species in its Wild State , Toronto 1972

Web links

- Bison bison in the Red List of Threatened Species of the IUCN 2008. Posted by: C. Gates, K. Aune, 2008. Accessed on December 31 of 2008.

- Video: bison bison - step . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 1954, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / E-13 .

- National Bison Association: bisoncentral.com

- German Bison Breeding Association V .: bison-zuchtverband.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Margaret Mary Meagher, The Bison of Yellowstone National Park , [Washington DC] 1973, pp. 38f.

- ↑ Mary Meager, Bison bison , in: Mammalian Species 266 (1986) pp. 1-8, here p. 1.

- ^ Meagher, Bison of Yellowstone , p. 39.

- ↑ a b Meagher, Bison bison , p. 1.

- ↑ On this and the following Hal W. Reynolds / C. Cormack Gates / Randal D. Glaholt: Bison (Bison bison) , in: George A. Feldhamer / Bruce C. Thompson / Joseph A. Chapman (eds.), Wild Mammals of North America. Biology, Management, and Conservation, 2nd edition, Baltimore / London 2003, pp. 1009-1060, here p. 1013.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , pp. 1011-1013.

- ^ Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , p. 1011.

- ↑ C. Cormack Gates / Curtis H. Freese / Peter JP Gogan / Mandy Kotzman (eds.): American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 , Gland 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ a b Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , p. 1012.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. C. Cormack Gates / Kevin Ellison, section “Numerical and Geographic Status”, in: Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , pp. 55–62, here p. 55.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 58.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 58.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 43.

- ^ Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , p. 1036.

- ↑ Bryan R. Coppedge, David M. Leslie, Jr. and James H. Shaw, Botanical Composition of Bison Diets on Tallgrass Prairie in Oklahoma , in: Journal of Range Management 51, 4 (1998), pp. 379-382, here P. 380f.

- ↑ Coppedge [u. a.], Botanical Composition of Bison Diets , p. 381.

- ↑ Coppedge [u. a.], Botanical Composition of Bison Diets , p. 380, table 1.

- ↑ Claudia A. Rosas, David M. Engle, James H. Shaw and Michael W. Palmer, Seed Dispersal by Bison bison in a Tallgrass Prairie , in: Journal of Vegetation Science 19, 6 (2008), pp. 769-778.

- ↑ Rosas [u. a.], Seed Dispersal by Bison bison , p. 171.

- ↑ a b Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , p. 1021.

- ↑ Krysten L. Schuler / David M. Leslie, Jr. / James H. Shaw / Eric J. Maichak Source, Temporal-Spatial Distribution of American Bison (Bison bison) in a Tallgrass Prairie Fire Mosaic , in: Journal of Mammalogy 87, 3 (2006), pp. 539-544, here p. 541.

- ^ SC Hess, Aerial survey methodology for bison population estimation in Yellowstone National Park , Ph.D. dissertation, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 2002, p. 55.

- ↑ a b Reynolds [u. a.], Bison (Bison bison) , p. 1022.

- ^ William A. Fuller, Behavior and Social Organization of the Wild Bison of Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada , in: Arctic 13, 1 (1960), pp. 2-19, here p. 8.

- ^ Lott, American Bison , p. 6.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Dale F. Lott, Sexual and aggressive behavior of adult male American bison (Bison bison) in: V. Geist / FR Walther (Ed.), The behavior of ungulates and its relation to management, IUCN Morges, Switzerland 1974, p. 382 -394.

- ↑ For more information on this behavior, Lott, Sexual and aggressive behavior , p. 384.

- ↑ Christine R. Maher / John A. Byers, Age-Related Changes in Reproductive Effort of Male Bison , in: Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 21, 2 (1987), pp. 91-96. Also Lott, American Bison , p. 13f.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Jerry O. Wolff, Breeding Strategies, Mate Choice, and Reproductive Success in American Bison , in: Oikos 83, 3 (1998), pp. 529-544, here: p. 535.

- ↑ Allen T. Rutberg, Birth Synchrony in American bison (Bison bison): Response to Predation or season? , in: Journal of Mammalogy 65, 3 (1984), pp. 418-423, here p. 418.

- ↑ Wolff, Breeding Strategies , p. 530.

- ↑ Douglas W. Smith / L. David Mech / Mary Meagher / Wendy E. Clark / Rosemary Jaffe / Michael K. Phillips and John A. Mack, Wolf-Bison Interactions in Yellowstone National Park , in: Journal of Mammalogy 81, 4 ( 2000), pp. 1128-1135.

- ↑ a b Smith, Wolf Bison Interactions , p 1,132th

- ^ Frank Gilbert Roe, The North American Buffalo. A Critical Study of the Species in its Wild State , Toronto 1972, pp. 157f.

- ↑ Travis Wyman, Grizzly Bear Predation on a Bull Bison in Yellowstone National Park , in: Ursus 13 (2002), pp. 375–377, here p. 375.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Keith Aune / C. Cormack Gates, section “Reportable or Notifiable Diseases”, in: Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , pp. 27–37, here p. 29.

- ^ Mary Meagher / Margaret E. Meyer, On the Origin of Brucellosis in Bison of Yellowstone National Park: A Review , in: Conservation Biology, 8, 3 (1994), pp. 645-653, here p. 650.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 33.

- ↑ Julie A. Fuller / Robert A. Garrott / PJ White / Keith E. Aune / Thomas J. Roffe and Jack C. Rhyan, Reproduction and Survival of Yellowstone Bison , in: The Journal of Wildlife Management 71, 7 (2007), Pp. 2365-2372, here p. 2371.

- ↑ Meagher, Bison bison , p. 6.

- ^ A b Meagher, Bison of Yellowstone , p. 69.

- ^ Meagher, Bison of Yellowstone , pp. 69f.

- ^ Robert S. Pfannenstiel / Mark G. Ruder, Colonization of bison (Bison bison) wallows in a tallgrass prairie by Culicoides spp (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) , in: Journal of Vector Ecology 40, 1 (2015), pp. 187-190 .

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Meagher, Bison bison , p. 6.

- ^ Meagher, Bison of Yellowstone , p. 74.

- ↑ Eric Chaline, 50 animals that changed our world , Bern 2014, ISBN 978-3-258-07855-7 , p. 23.

- ↑ See Jerry N. McDonald, North American bison: their classification and evolution , Berkeley [u. a.] 1981, plate 1.

- ^ A b Alexandre Hassanin / Anne Ropiquet, Molecular phylogeny of the tribe Bovini (Bovidae, Bovinae) and the taxonomic status of the Kouprey, Bos sauveli Urbain 1937 , in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33 (2004), pp. 896-907.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Delaney P. Boyd / Gregory A. Wilson / C. Cormack Gates, section “Taxonomy and Nomenclature”, in: Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , pp. 13-18.

- ^ Carl von Linné, Systema Naturae , 10th edition, Volume 1, p. 71.

- ↑ Morris F. Skinner / Ove C. Kaisen, The fossil bison of Alaska and preliminary revision of the genus , in: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 89 (1947), pp. 123-256, here p. 159.

- ^ Charles Knight, Sketches in Natural History: History of the Mammalia , Vol. 5 and 6, London 1849, pp. 408-412.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 13.

- ↑ Fayasal Bibi, A multi-calibrated mitochondrial phylogeny of extant Bovidae (Artiodactyla, Ruminantia) and the importance of the fossil record to systematics , in: BMC Evolutionary Biology 13 (2013), p. 166

- ↑ Alexandre Hassanin / Frédéric Delsuc / Anne Ropiquet / Catrin Hammer / Bettine Jansen van Vuuren / Conrad Matthee / Manuel Ruiz-Garcia / François Catzeflis / Veronika Areskoug / Trung Thanh Nguyen / Arnaud Couloux, Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactalia, Lauria (Mammia ), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes , in: Comptes Rendus Palevol 335 (2012), pp. 32-50

- ↑ Chengzhong Yang / Changkui Xiang / Wenhua Qi / Shan Xia / Feiyun Tu / Xiuyue Zhang / Timothy Moermond / Bisong Yue, Phylogenetic analyzes and improved resolution of the family Bovidae based on complete mitochondrial genomes , in: Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 48 (2013) , Pp. 136-143.

- ↑ Marie-Claude Marsolier-Kergoat / Pauline Palacio / Véronique Berthonaud / Frédéric Maksud / Thomas Stafford / Robert Bégouën / Jean-Marc Elalouf, Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave , in: ONE 10, 6 (2015), p. E0128267 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0128267 .

- ↑ Pauline Palacio / Véronique Berthonaud / Claude Guérin / Josie Lambourdière / Frédéric Maksud / Michel Philippe / Delphine Plaire / Thomas Stafford / Marie-Claude Marsolier-Kergoat / Jean-Marc Elalouf, Genome data on the extinct Bison schoetensacki establish it as a sister species of the extant European bison (Bison bonasus) , in: BMC Evolutionary Biology 17 (2017), p. 48 doi: 10.1186 / s12862-017-0894-2 .

- ↑ Samuel N. Rhoads, Notes on living and extinct species of American bovidae , in: Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 49 (1897), pp. 483-502.

- ↑ Valerius Geist, Phantom Subspecies: The Wood Bison Bison bison “athabascae” Rhoads 1897 Is Not a Valid Taxon, but an Ecotype , in: Arctic 44, 4 (1991), pp. 283-300.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 15.

- ↑ Gregory A. Wilson / Curtis Strobeck, Genetic variation within and relatedness among wood and plains bison populations , in: Genome 42, 3 (1999), pp. 483-496.

- ↑ Matthew A. Cronin / Michael D. MacNeil / Ninh Vu / Vicki Leesburg / Harvey D. Blackburn / James N. Derr, Genetic Variation and Differentiation of Bison (Bison bison) Subspecies and Cattle (Bos taurus) Breeds and Subspecies , in: Journal of Heredity 104, 4 (2013), pp. 500-509.

- ↑ Jeff M. Martin / Jim I. Mead / Perry S. Barboza: Bison body size and climate change , In: Ecology and Evolution 8, 9 (2018), pp. 4564–4574.

- ↑ Duane Froese / Mathias Stiller / Peter D. Heintzman / Alberto V. Reyes / Grant D. Zazula / André ER Soares / Matthias Meyere / Elizabeth Hall / Britta JL Jensen / Lee J. Arnold / Ross DE MacPhee / Beth Shapiro: Fossil and genomic evidence constrains the timing of bison arrival in North America , in: PNAS 114, 13 (2017), pp. 3457-3462.

- ^ R. Dale Guthrie: Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe. University of Chicago Press, 1990

- ↑ Ralf-Dietrich Kahlke: The origin, development and spread of the Upper Pleistocene Mammuthus-Coelodonta Faunenkomplexes in Eurasia (large mammals) , in: Abhandlungen der Senckenbergische Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 546 (1994), pp. 1–115 (pp. 42–45 ).

- ↑ Patrick J. Lewis / Eileen Johnson / Briggs Buchanan / Steven E. Churchill: The Evolution of Bison bison: A View from the Southern Plains , in: Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 78 (2007), pp. 197-204.

- ↑ Jessica L. Metcalf / Stefan Prost / David Nogués-Bravo / Eric G. DeChaine / Christian Anderson / Persaram Batra / Miguel B. Araújo / Alan Cooper / Robert P. Guralnick: Integrating multiple lines of evidence into historical biogeography hypothesis testing: a Bison bisoncase study , in: Proceedings of the Royal Society B281 (2014), S. 20132782, doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2013.2782 .

- ^ National Park Service, Yellowstone - Frequently Asked Questions: Bison , last accessed June 8, 2016.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. James H. Shaw, How Many Bison Originally Populated Western Rangelands? , in: Rangelands 17, 5 (1995), pp. 148-150.

- ^ William T. Hornaday, The extermination of the American bison with a sketch of its discovery and life history , Washington, DC 1889, p. 391.

- ↑ Ernest T. Seton, The lives of game animals , 4 volumes, Garden City, NJ 1929, quoted here from Shaw, How Many Bison , p. 149.

- ↑ Tom McHugh, The time of the buffalo , New York 1972, here quoted from the reprint from 2004, pp. 16f.

- ^ Dale F. Lott, American Bison - A Natural History , London 2002, "America's bison population was probably less than 30 million - perhaps, on average, 3 to 6 million less," p. 76.

- ↑ Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 8.

- ↑ a b c Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 9.

- ↑ J. Shaw / M. Meagher, Bison , in: Stephen Desmarais / Paul R. Krausman (Eds.), Ecology and Management of Large Mammals in North America, Upper Saddle River, NJ 2000, pp. 447-466, cited here after Gates [u. a.], American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation , p. 9.

- ^ The bison - past, present and future ( Memento from October 7, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ C. Gates / K. Aune, Bison bison , The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2008, last accessed on June 18, 2016.

- ↑ Most recently Robert L. Kelly / David Hurst Thomas, Archeology , Boston, MA 2016, p. 69.

- ↑ Liz Bryan, Stone by Stone. Exploring Ancient Sites on the Canadian Plains , 2nd ed., Surrey, BC 2015, p. 36.

- ↑ E.g. Madison Buffalo Jump in Montana , 45 ° 47 ′ 32 ″ N , 111 ° 27 ′ 49 ″ W

- ↑ Shipwrecks: Report on the unfortunate voyage of the Narváez expedition to the south coast of North America 1527–1536 , translation, introduction and scientific processing by Franz Termer, 2nd, completely revised edition, Renner 1963, p. 79.

- ↑ M. Scott Taylor, Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison , in: American Economic Review 101, 7 (2011), pp. 3162-3195, cited here from the January 2011 working paper .

- ↑ Robert Saemann-Ischenko: Legendary tasty bisons , in: Zeit Online from September 1, 2011, last accessed on June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Bloomberg News: Bison Returned From the Brink Just in Time for Climate Change . July 31, 2017

- ^ New York Times: As Bison Becomes More Popular, Two Views Emerge on How to Treat Them , February 9, 2016

- ^ Department of the Interior: DOI Bison Report - Looking Forward , 2014.

- ↑ Sean Reichard: Crow Tribe Wants to Join Tribal Hunts of Yellowstone Bison. Article on yellowstoneinsider.com, February 16, 2018, accessed February 18, 2020.

- ↑ Danny Lewis, The Bison Is Now the Official Mammal of the United States , in: Smithsonian, May 9, 2016, last accessed June 7, 2016.

- ^ A new park to save the plains , in: The Kansas City Star, November 15, 2009, p. B7

- ↑ Katharina Cypzirsch, Christian Schneider: Guide to bison keeping in Germany - history, keeping, breeding, animal health, use and insurance. Schüling Verlag, Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-86523-203-8

- ↑ Homepage of the German Bison Breeding Association

- ↑ Article Tanzende Bisons on SAT-1, March 27, 2018, accessed on August 5, 2020.