Cem Sultan

Cem (جم بن محمد / Cem b. Meḥemmed ; born December 23, 1459 in Edirne ; died February 25, 1495 in Naples ) was a Turkish prince and poet who ruled as sultan over a small part of the Ottoman Empire for about 18 days . After losing the battle for the Ottoman throne against his brother Bayezid II , he sought asylum on the island of Rhodes . As a pledge against his brother's expansion plans, he spent the rest of his life in exile in Europe. In France , where he lived for almost seven years, poems and novels tell of the adventures and love affairs ascribed to him .

Life

family

Cem was the third son of Sultan Mehmed II. His mother was one of the concubines from the harem of Mehmed II, whose name is Çiçek ("flower"). Since Islamic laws forbade the enslavement of Islamic believers, most harem concubines were Christian slaves. Cem's mother was believed to be a Serbian princess.

Cem was the only son Mehmed fathered after ascending the throne. The two older sons were the future Bayezid II , who was born in 1447 and whose mother was the concubine Gülbahar, and Mustafa, whom he fathered with the concubine Gülşah, and who was born in 1450.

Both Bayezid and Mustafa had been appointed prince governors (Çelebi Sulṭān) by their father in 1457 and were sent to Amasya and Manisa, respectively . They were nine and seven years old at the time. They took up their posts accompanied by their respective mothers and accompanied by teachers and advisers ( Lālā ) . Like her brother Cem later, they received a careful education in geography , history , literature and science .

Prince-Governor, Imperial Administrator and Provincial Governor

Similar to his two older brothers, Cem was also appointed Prince-Governor ( Çelebi Sulṭān ) by his father . At the age of ten he went to Kastamonu in northern Anatolia with his mother and two Lālā . According to the traditions of Saʿdeddīn, his teachers also taught him in Persian and Arabic .

In 1470/71 (H 875) Cem returned to Istanbul for the first time on the occasion of his circumcision for a short time.

When Mehmed II went on a campaign against Uzun Hasan together with his two eldest sons in 1473 , Cem was ordered to Edirne as imperial administrator . After no news from Eastern Anatolia for a long time, rumors increased that Mehmed had fallen and his army had been destroyed by the Aq Qoyunlu . On the advice of his two Lālā Nasuh and Kara Süleyman, he accepted the homage and the oath of allegiance ( bīʿat ) of the high dignitaries as a pretender to the throne . Shortly afterwards news came that Mehmed's campaign had been successful and that both he and his sons were safe. Cem fled because he feared his father's wrath. His father forgave him, but had Nasuh and Kara Suleyman executed.

Mustafa, Cem's second eldest brother, fell seriously ill in the spring of 1474 and, after he died in June, his father installed Cem in his place as provincial governor of Karaman , based in Konya .

Diplomatic duties

The Hospitallers on Rhodes represented an obstacle to Mehmed II for further expansion across the Mediterranean. The order allied itself in 1478 with the Mamluk Sultan Kait-Bay in order to be able to counter the Ottoman threat. Thereupon Mehmed II brought Cem to Istanbul in 1479 and commissioned him to conduct diplomatic negotiations with the Johanniter. Permanent peace was offered to the Hospitallers through an envoy if they paid an annual tribute. This was rejected, but an armistice was reached, which only lasted until May 23, 1480, when Mehmed II attacked Rhodes - ultimately without success.

Battle for the throne

Mehmed II died on May 3, 1481. He was only 49 years old. The Turkish court was split between the followers of Cem and those of Bayezid. Cems supporters included the Grand Vizier Karamani Mehmed Pascha and the long-time Commander in Chief Gedik Ahmed Pascha. On Bayezid's side, however, were most of the viziers and - what turned out to be much more decisive - the commander of the Janissaries .

The Grand Vizier Karamani Mehmed Pasha had tried to keep the death of Mehmed II secret for as long as possible. The body of Mehmed II was transferred to Istanbul on the pretext that the ruler had to go to the hammam. The Grand Vizier sent messengers to notify Cem in distant Konya so that he could rush to Istanbul and claim the throne. The messengers, however, were intercepted by followers of Bayezid. The death of Mehmed II was not hidden from the Janissaries either. They stormed the Topkapi Palace, where Mehmed II was laid out, killed Karamani Mehmed Pasha, paraded through the streets of Istanbul and proclaimed Bayezid as the new sultan. Bayezid's eleven-year-old son, Korkud , who was brought up in the Topkapi similar to Cem's eldest son, was appointed regent who would hold the throne for him until Bayezid returned from Amasya .

Cem had only found out about his father's death when the funeral of Mehmed II had already taken place and Bayezid was girded with the sword of his ancestor Osman I - a ceremony corresponding to the coronation in a Christian monarchy . Cem decided to fight for the throne and gathered troops in Anatolia. He moved to Bursa via Akşehir , Afyonkarahisar , Kütahya and Eskişehir . About 20,000 men accompanied him when he reached Bursa, which he took after a brief resistance. On June 2, 1481, he was praised as the new sultan in the mosques of Bursa; At the same time, as Sultan Cem, he had the first silver coins minted . With both measures he wanted to signal that he ruled as sultan over at least this part of the Ottoman Empire. He proposed to his brother Bayezid to divide the Ottoman Empire among themselves. Bayezid was to rule over the European provinces from Istanbul. Cem wanted to rule Anatolia from Bursa. Bayezid rejected this proposal without hesitation and, for his part, gathered troops in İznik , about 50 kilometers northeast of Bursa. In the vicinity of Yenişehir on July 22nd, 1481 the decisive battle between the brothers broke out. The 20,000 men under the leadership of Cem faced 40,000 under the leadership of Bayezid. Bayezid had also bribed one of Cems's military leaders, who ran over to him during the battle and decided the battle.

Escape to Cairo

Cem fled with his family and a small band of supporters immediately after the battle. The next morning they reached Eskişehir , which was about ninety kilometers south-east of Yenişehir. There they were attacked by a group of Turkmen who stole their last belongings. They reached Konya on June 26th, where they were safe for the moment. However, they set out three days later to flee further in the direction of southeastern Anatolia. They would then reach Mamluk territory, where they believed they were safe from further persecution by Bayezid. From Ereğli they crossed the Taurus Mountains to get to Tarsus . Cem and his followers - now a group of two hundred to three hundred - received a hospitable reception from the local princes. They were vassals of the Mamluks and were thus hostile to Sultan Bayezid. Their flight led Cem and his followers on from İskenderun on the Mediterranean coast via Aleppo , Hama , Homs and Baalbek to Damascus . As a guest of the Mamluk regent, they stayed there for six weeks. They then traveled via Jerusalem , Hebron and Gaza to Cairo , which they reached in early October.

Bayezid had Cem persecuted by the commander-in-chief of the Janissaries Gedik Ahmed Pascha. His failure to confront him while he was on the run led to Gedik Ahmed Pasha's arrest. The Janissaries, however, reacted to the arrest of their commander-in-chief with a revolt, stormed the palace and demanded that Bayezid be released immediately. Since Bayezid still feared that the Janissaries would stand behind Cem, he followed their demands. Gedik Ahmed Pasha not only got his title back as vizier , but was also reinstated as commander-in-chief of the Janissaries.

Stay in Cairo

The Mamluk Sultan El-Ashraf Seyfeddin Kait-Bay was the most powerful opponent of the Ottomans. When the news reached him that Cem and his followers were approaching Cairo, he sent his most powerful court officials to meet him with the message that he was welcome at the court of Cairo and safe from his brother Bayezid. Sultan Kait-Bay himself was due to the fact that the succession disputes within the Ottoman Empire continued. For the time being, however, he did not respond to Cems' request to support him in his fight for the throne. Instead, he tried to mediate between the two brothers while Cem went on the Hajj to Mecca and Medina . Bayezid's only concession to Cem was an offer to help him financially if he settled near Jerusalem.

Another fight for the succession

Cem found Kasım Bey's offer to accompany him on a campaign against Bayezid more attractive than his brother's offer. Kasım Bey had ruled the area of Karamania until Ottoman troops conquered this region. Kasım Bey had also informed Cem that Mehmed Agha - once commander-in-chief of the Janissaries under Mehmed II - would support Cem in his struggle for the Ottoman throne. Financially supported by Sultan Kait-Bay and accompanied by a Mamluk troop of 2,000 soldiers, Cem set out on March 26, 1482 to return to Adana , where Kasım Bey and Mehmed Agha were waiting with their troops. His family - including his mother, his son Murad and his mother, his daughter Gevher Melek and several women from his harem - he left behind under the protection of the Mamluk sultan.

Bayezid was well informed through spies about his brother's plans and his troop movements in southern Anatolia. While Cem was marching across the high plateau of Anatolia with Kasım Bey and Mehmed Agha, he assembled an army of 200,000 men. However, he had to expect that, similar to Mehmed Agha, even more troops would join Cem. He tried to buy the loyalty of his troops with generous gifts of money.

Cem suffered another defeat. After the combined army of Cem, Kasım Bey and Mehmed Agha tried in vain to take the city of Konya , they separated. Mehmed Agha should try to take Ankara . There he was defeated, however, in a battle against one of the governors of Bayezid. Mehmed Agha himself was killed in the battle. When the news of the death reached Mehmed Aghas Cem and Kasım Bey, they withdrew again to the impassable Taurus Mountains in front of the approaching troops of Bayezid .

Escape to Rhodes

After the renewed defeat, Cem had considered fleeing to Persia to avoid capture by his brother's troops. However, Kasım Bey advised him to seek exile in Europe. Cem initially wrote a letter to the Republic of Venice with his request for asylum . Venice declined, however, with reference to the existing peace treaty. Bayezid also found out about Cem's advances through his spies and then reaffirmed the existing peace treaty with Venice.

After the rejection by Venice, Cem turned to the Grand Master of the Order of St. John , Pierre d'Aubusson , whom he had met during the peace negotiations that had failed at the time and with whom he had got on well. D'Aubusson reacted very quickly to Cem's request, realizing that Cem could play an important role in preventing his brother from further conquering campaigns in Europe. The terms of exile were negotiated by two of Cem's confidants. At least one of his confidants had doubts about the reliability of the promises of the knights. However, Cem no longer had any room for negotiation. In July 1482, in the port of Korykos , he sought protection on a Karaman galley with a few remaining loyal followers . The sails were set and Cem narrowly escaped an advancing cavalry unit of Bayezids. After three days he was taken over by the Johanniter squadron near Anamur and brought to Rhodes. Bayezid's troops immediately occupied Korykos and Anamur.

On the trip to Rhodes, Cem was accompanied by his taster Ayas Bey, his mother's brother Ali Bey, his secretary Haydar Bey and several members of his former court. They reached Rhodes on July 29, 1482. There Cem was assigned a house. D'Aubusson had meanwhile informed Pope Sixtus IV that Cem was in his custody and asked him for permission to start negotiations with Bayezid. As soon as the Pope's approval was given, d'Aubusson informed Bayezid that from now on the order would no longer make any tribute payments. Instead, he demanded that the inhabitants of Rhodes be allowed to trade freely throughout the Ottoman Empire and that they only have to pay normal duties and fees. Bayezid was supposed to cover the cost of maintaining Cem and his entourage through an annual payment of 45,000 ducats. In return, d'Aubusson assured the Sultan that he would ensure that Cem would not wage another war against his brother.

Cem, in turn, assured d'Aubusson that the Christian princes would have an eternal friend in him if they supported him in conquering his throne. He further assured that all Christian territories that were under Ottoman rule should be returned. He derived his claim to the Ottoman throne from the fact that he was born when his father was already a sultan. D'Aubusson immediately complied with Cem's wish to bring some of his entourage who had stayed behind in Anatolia to Rhodes as well.

Asylum in France and Italy

In the custody of the Johanniter

Since Rhodes was not considered safe enough, Pierre d'Aubusson sent Cem to France. Cem had agreed, having been assured that he could get to Hungary from France. This would have brought him closer to his goal of reaching Rumelia and from there to fight for rule over the Ottoman Empire.

In France, Cem was imprisoned in various castles of the order from 1482 to 1489. It was guarded by only a few knights, among whom Pierre d'Aubusson's nephew Guy de Blanchefort is said to have belonged. If possible, Cem shouldn't have the impression that he was a prisoner of war. But the Johanniter wanted to keep it under control as a source of money and bargaining chip for political negotiations with Bayezit II. Cems' whereabouts include the port cities of Villefranche-sur-Mer , Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne , Chambéry , Rumilly, Péage-de-Roussillon and Rochechinard Castle, among others that are controversial in literature . Cem spent the last two years of his forced exile in Bourganeuf , the seat of the Johannite Grand Prior of the Auvergne , in a seven-story round tower built for him.

In the hands of the Popes and the King of France

On March 4, 1489, the Johanniter delivered Cem "for the good of Christendom" to Pope Innocent VIII , who had competed with the kings of Hungary and Naples for possession of this valuable hostage . From then on, the Pope could claim the annual payment from Istanbul for himself. Bayezid, who had protested against the transfer to Rome, finally sent the Pope, provided he would take over the agreements with the Hospitallers, 120,000 gold pieces as an advance payment for the first three years of Cem's protective custody . Shortly afterwards, on March 9, 1489, Pierre d'Aubusson received the cardinal dignity from the Pope in return for himself and the subsequent Grand Master of St. John . Cem's presence in Rome increased the Pope's international prestige. In letters to the Christian rulers of Europe, he advocated a crusade against the Ottomans, for which the time was now favorable. However, this plan was not carried out.

Pope Alexander VI, who succeeded Innocent VIII in 1492, wanted to continue the agreements with the Ottoman Sultan, but Bayezid II initially refused to make the annual payments. The Pope's assertion in 1494 that the French King Charles VIII , who was marching on Rome, wanted to bring Cem into his power and attack the Ottoman Empire together with the kings of England and Spain and the Roman-German King Maximilian I, led Bayezid to give in. The 40,000 pieces of gold he sent to the Pope were taken from the messenger in Senigallia by Giovanni della Rovere , and Bayezid's letters to the Pope were also captured. In one of the letters Bayezid is said to have offered the Pope 300,000 gold pieces in case he had Cem murdered and his body brought to Istanbul.

In November 1494 Charles VIII entered Rome. The Pope was forced to hand over Cem, who he had meanwhile interned in Castel Sant'Angelo , to the king, who took Cem into custody at the end of December 1494 and took him with him on his campaign to Naples.

Death and transfer of the body to Bursa

Cem is said to be seriously ill on the way to Naples. He was unable to ride and was brought to Castel Capuano in Naples in a sedan chair . Called doctors found that Cem's face, eyes and throat were swollen. According to Saʿdeddīn, Cem dictated his last will and a will in the face of approaching death. He died on the morning of February 25, 1495 (29 Dschumada I. 900) in Castel Capuano. There is no verifiable evidence for the story spread in later chronicles that Cem was killed on behalf of Bayezid II or the Pope while being shaved by an injury with a poisoned razor. Bayezid II learned of Cem's death in April 1495 and made him known throughout the empire through public prayers for Cem's soul. It was not until 1499 that he was able to have the embalmed corpse - as ordered by Cem shortly before his death - transferred to dār-ı İslām in Bursa, where Cem finally found rest in his brother Mustafa's mausoleum.

progeny

Cem probably had five children, four of whom were born in Kastamonu. Information on this is contradictory and hardly supported by documents.

The following list is based mainly on Halil İnalcık (EI, 1991), John Freely (2004) and the monumental Diarii by Marino Sanudo, written between 1496 and 1531, cited and processed by Freely .

- The first child is said to have been a daughter. Neither her name nor that of her mother are known.

A son Abd'llah is also named as the firstborn (* 1473 in Kastamonu; † 1481 in Bursa). - Aisha (* 1473 in Kastamonu, † 1505 in Constantinople); in 1503 she married Damat Mehmed Ney, a son of Sinan Pascha, the Beylerbey of Anatolia.

- Oğuzhan (* 1474 Kastamonu; executed 1482 in Constantinople); Oğuzhan was brought to Constantinople with his mother, Cems concubine Severid. One reason for this could have been that Meḥmed II wanted to hold him hostage in order to be able to put Cem under pressure if necessary. Bayezid II had him killed in 1482.

- Gevhermulik; married Sultan an-Nasir Muhammad II in Cairo in 1491; he was killed in 1498; Gevhermulik married in Constantinople in 1504 Muhammad Bey, another son of Sinan Pasha, the Beylerbey of Anatolia.

- Murad (* 1475 Konya; 1522 executed in Rhodes); he converted to Christianity and from then on bore the name Mehmed Pierre; 1492 he was by Pope Alexander VI. appointed Principe Romano and Visconte de Sayd by the King of Naples ; he was also recognized as a patrician of Rome. He is said to have married Maria Concetta Doria, a daughter of the consul of Genoa. From this marriage Murad is said to have had two daughters and three sons, one of whom, named Pietro Oshin Sayd, is claimed to be an ancestor by today's Sayd families in Malta . He escaped when Suleyman I. Murad and a son of Murad were executed in Rhodes in 1522.

Lore

The main sources about the life of Cem are the anonymously written biography Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem (' Incidents of Sulṭān Cem') and the Persian- language work Hašt behešt ('eight paradises') by Idrīs Bidlīsī and, based on these, the Tācü t- tevārīḫ ('Crown of Chronicles') of Saʿdeddīn . The author of the Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem is a companion of the prince, presumably the poet Haydar Bey , who lived in exile with Cem Sultan, served him there as his secretary and, after the prince's death, returned his property to Turkey brought. In 1892 the French Louis Thuasne published a book entitled Djem-Sultan, fils de Mohammed II, frère de Bayezid II. (1459–1495) [...] , which was based on the French translation of the Tācü t-tevārīḫ as well processed contemporary European sources.

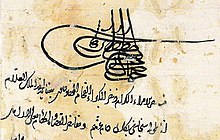

Portraits

Cem's appearance has been described several times by eyewitnesses. In contrast, there is no clearly identifiable portrait.

At the request of Mehmed II, the painter Gentile Bellini came to Istanbul in January 1478 and painted at least one portrait of the Turkish sultan, which was completed on November 23, 1480. Another painting was discovered in a private collection in 1950 and is now attributed to Bellini. It shows Mehmed II in half profile and opposite a young man who is also shown in half profile. An inauthentic inscription on the back of the painting names Mehmed and his son as portrayed. Due to the youthfulness of the person depicted on the left, it is now assumed that Cem was depicted here and not his older brother Bayezid - provided that it is a real portrait and not a fictional character. Cem was actually in Istanbul at the time Bellini was working in Istanbul.

Two bearded, Turkish-looking figures on Pinturicchio's murals, which are considered Cem's portraits, are, as Joseph von Karabacek already established, a fairly accurate ( recte or reversed ) copy of a Bellini drawing in shape and face , which is by no means a portrait of Cem . In addition, another figure from a Pinturicchio fresco, a stately, bearded rider, is mistaken for Cem. These representations correspond to the preference for Turkish costumes and customs developed by Cem and his surroundings in Rome, which meant that even Juan Borgia , the favorite son of Pope Alexander VI, liked to dress like a Turk. In contrast to Pinturicchio's murals, eyewitnesses described Cem as being beardless. He squinted, had small ears, a small mouth with full lips and small, fleshy hands, and he liked to dress magnificently. This corresponds to a portrait from the Vienna Codex 8615, which is probably a copy after a lost original by Gentile Bellini or Costanzo da Ferrara.

The depiction of a banquet at Pierre d'Aubusson's by the Maître du cardinal de Bourbon , published by Guillaume Caoursin , Vice Chancellor of the Order of St. John, from 1482 shows Cem beardless and appears authentic. This corresponds to Caoursin's description of Cem's appearance given by Joseph von Karabacek.

In one on an incipit of an alto from Ms. Capp. S is. 41 of the young Turks depicted in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana , it is considered whether Cem can be portrayed here. When Ms. 41 is the first edition of the Missa La Sol Fa Re Mi by Josquin Desprez , who probably was a singer in the papal chapel in time, was staying as Cem in Rome. The person pictured holds a tape in his right hand that reads "LESSE: FAIRE: A MI:". This saying is interpreted on the one hand as a verbalization of the tone names La Sol Fa Re Mi , but on the other hand as a saying of the possibly depicted Cem. There are no documents suggesting a connection between Cem and Josquin Desprez.

A posthumous portrait (after Peter Paul Seuin) published in 1676 showing a beardless Cem can be found in: Dominique Bouhours: Histoire de Pierre d'Aubusson, grand-maistre de Rhodes. chez Sebastien Mabre-Cramoisy, Paris 1676.

Works

Cem learned Persian and Arabic as a child. As Prince-Governor of Kastamonu, he also received instruction in this regard from his two Lālā Nasuh and Kara Suleyman. They encouraged his keen interest in the literature of both languages. In Konya, as provincial governor of Karaman, Cem surrounded himself with poets and literary officials, scholars and patrons.

These early linguistic and literary experiences formed the basis of Cem's own poems, which are inspired by Persian poets such as Nezāmi , Salmān-e Sāvaji, Hāfiz, and Jami, as well as by Turkish poets such as Ahmed Pascha, Šayḵi, and Nejāti Beg.

- Cem wrote a Persian and a Turkish Dīwān .

- For Mehmed II he made a Turkish translation of Mesnevis Cemşid ü Hurşîd by the poet Salmān-e Sāvaǧī from the 14th century.

- A poem called Fāl-i Reyḥān-i Sulṭān Cem is also written in Turkish.

- In correspondence, Cem and his brother and competitor sometimes addressed each other with poetry.

- On the death of his son Oğuzhan, Cem wrote a three-part elegy (Turkish: mersiye ) consisting of 33 two-line texts .

literature

Biographies and Monographs

- İsmail Hikmet Ertaylan: Sultan Cem. Milli Eğitim Basımevi, İstanbul 1951 (Turkish)

- John Freely: Jem Sultan. The Adventures of a Captive Turkish Prince in Renaissance Europe. HarperCollins, London 2004 (English)

- Louis Thuasne: Djem-Sultan, fils de Mohammed II, frére de Bayezid II, (1459–1495) d'aprés les documents originaux en grande partie inédits; étude sur la question d'orient á la fin du XVe siécle. Leroux, Paris 1892 (French)

- Nicolas Vatin: Sultan Djem. Un prince ottoman dans l'Europe du XV e siècle d'après deux sources contemporaines: Vâḳıʿât-ı Sulṭân Cem, œuvres de Guillaume Caoursin. Imprimerie de la Société Turque d'Histoire, Ankara 1997, ISBN 975-16-0832-5 (French)

Lexicon article

- Cavid Baysun: Cem. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi . Vol. 3, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1977, pp. 69-81.

- Halil İnalcık: Dj em. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Vol. 2, Brill, Leiden 1991, pp. 529-531.

- Osman G. Özgüdenli: Jem Solṭān. In: Encyclopædia Iranica . Vol. 14, Faszikel 6, 2008, p. 623 f. (available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jem-soltan- , accessed January 19, 2018).

- Mahmut H. Şakiroğlu: Cem Sultan. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi . Vol. 7, Istanbul 1993, pp. 283 f. ( PDF; 1.6 MB ).

Individual aspects

- Halil İnalcık: A case study in Renaissance diplomacy. The agreement between Innocent VIII. And Bayezid II on Djem Sultan. Journal of Turkish Studies 3, 1979, pp. 209-233.

Historical novels

- Adolphe d'Archiac: Zizim et les chévaliers de Rhodes: roman histor. you XVe siècle. Bridelle, Paris 1828.

- Jean-Marie Chevrier: Zizim: ou l'épopée tragique et dérisoire d'un prince ottoman. Albin Michel, Paris 1993.

- Wera Mutaftschiewa : pawn of church and throne. Rütten and Loening, Berlin 1971 (translation by Hartmut Herboth, original title: Случаят Джем, 1966).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Joseph von Karabacek: Occidental artists to Constantinople in the XV. and XVI. Century. Italian artist at the court of Muhammad II the Conqueror. 1451-1481. Vienna 1918, pp. 53–60.

- ^ SUDOC, French union catalog . Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Halil İnalcık: Dj em. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Vol. 2, Brill, Leiden 1991, pp. 529-531.

- ↑ John Freely: Jem Sultan. The Adventures of a Captive Turkish Prince in Renaissance Europe. HarperCollins, London 2004, pp. 25-32.

- ↑ Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and his time. World striker at a turning point. 2nd edition, Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1959, p. 419 f.

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. 2nd improved edition, 1st volume, CA Hartlebens Verlag, Pest 1834, p. 611.

- ↑ John Freely: Jem Sultan. The Adventures of a Captive Turkish Prince in Renaissance Europe. HarperCollins, London 2004, p. 68 f.

- ↑ Description of the scene in Caoursin, Guillaume / Adelphus, Johannes: Historia Von Rhodis, How knightly she kept herself with the tyrannical keiser Machomet vß Türckye [n] funny vn [d] lieplich zu read, Strasbourg, 1513. Online im MDZ of the BSB. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ↑ a b Osman G. Özgüdenli: Jem Solṭān. In: Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 14, Faszikel 6, 2008, p. 623 f.

- ^ A b René Boudard: Le Sultan Zizim vu à travers les témoignages de quelques écrivains et artistes de la Renaissance. Turcica VII (1975), p. 138.

- ^ Mandell Creighton: A history of the Papacy during the period of the Reformation. Vol. 3. The Italian princes, 1464-1518. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2012, p. 194 f.

- ↑ John Freely: Jem Sultan. The Adventures of a Captive Turkish Prince in Renaissance Europe. HarperCollins, London 2004, p. 264.

- ↑ Ḫoca Saʿdeddīn: Tācü t-tevārīḫ. Volume 2, Ṭabʿḫāne-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1280 (1863), p. 39.

- ↑ John Freely: Jem Sultan. The Adventures of a Captive Turkish Prince in Renaissance Europe. HarperCollins, London 2004, pp. 271 f.

- ↑ Hedda Reindl: Men around Bāyezīd: a prosopographical study of the epoch of Sultan Bāyezīd II. (1481–1512). Schwarz, Berlin 1983, p. 304.

- ^ German translations of the execution order by Hans Joachim Kissling: On the personnel policy of Sultan Bājezīd II. In the western border areas of the Ottoman Empire. In: Hans-Georg Beck, Alois Schmaus (Hrsg.): Contributions to research on Southeast Europe. On the occasion of the II. International Balkanologists Congress in Athens 7.V. – 13.V.1970 (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 10). Trofenik, Munich 1970, pp. 107–116, here: p. 109 footnote 3; Richard F. Kreutel: The pious Sultan Bayezid. The history of his rule (1481–1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus (= Ottoman historians. Vol. 9) Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1978, ISBN 3-222-10469-7 , p. 280 f. Note 11.

- ^ Rinaldo Fulin et al. (Ed.): I Diarii di Marino Sanuto. 56 volumes, Venice 1879–1902.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: A case study in Renaissance diplomacy. The agreement between Innocent VIII. And Bayezid II on Djem Sultan. Journal of Turkish Studies 3 (1979), pp. 209-233. PDF at inalcik.com . Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ↑ Jürg Meyer zur Capellen: Gentile Bellini as a portrait painter at the court of Mehmet II. In: Neslihan Asutay-Effenberg, Ulrich Rehm (ed.): Sultan Mehmet II. Conqueror of Constantinople - patron of the arts. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2009. p. 158, note 16.

- ↑ Illustration in Karabacek . Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ Commons: File: Appartamento borgia, sala dei santi, disputa di santa caterina, dettaglio 2.jpg

- ^ August Schmarsow : Pinturicchio in Rome / a critical study. Spemann, Stuttgart 1882, p. 40.

- ↑ Commons: File: Le prince Djem reçu à la table de Pierre d'Aubusson.jpg

- ↑ Figure in MS.41. folio 39r. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Dawson Kiang: Josquin Desprez And A Possible Portrait Of The Ottoman Prince Jem In Cappella Sistina Ms. 41. In: Bibliothèque d'Humanisme Et Renaissance. 54 (2): 411-426 (1992).

- ↑ Dominique Bouhours: Histoire de Pierre d'Aubusson, grand-maistre de Rhodes. chez Sebastien Mabre-Cramoisy, Paris 1676, p. 203 (digitized version) . Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ For the elegy see Cemâl Kurnaz: Cem Sultan'ın Oğuz Han Mersiyesi: Bir Kaside mi, Üç Gazel mi? In: Türk Dili. Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi. Vol. 1996 / I, No. 530, February 1996, ISSN 1300-2155 , pp. 315-320 ( PDF; 123 kB ).

- ↑ PDF at inalcik.com . Retrieved January 20, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cem Sultan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jem (alternative spelling); Djem (alternative spelling); Zizim (alternative spelling) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Ottoman prince, sultan and poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 23, 1459 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Edirne |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 25, 1495 |

| Place of death | Naples |